Introduction

During viral outbreaks such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the perceived risk of infection with the virus increases emotional issues including fear, panic, worries and uncertainties.Reference Mertens, Gerritsen, Duijndam, Salemink and Engelhard1 The effects of fear of COVID-19 on psychological health were visualised during the early period of the pandemic in Bangladesh.Reference Mahmud, Talukder and Rahman2 The first COVID-19-related suicide case occurred on 25 March 2020, with an allegation of fear of COVID-19 as the suicide stressor;Reference Mamun and Griffiths3 whereas the first COVID-19 patient was diagnosed on 8 March 2020.Reference Sakib, Akter, Zohra, Bhuiyan, Mamun and Griffiths4 Extreme psychological effects (such as suicide) related to fear of COVID-19 have not only been observed in Bangladesh; several case-series studies from other countries have also been reported.Reference Dsouza, Quadros, Hyderabadwala and Mamun5,Reference Griffiths and Mamun6 Similarly, fear of infection was regarded as a prominent suicide factor in prior pandemics.Reference Cheung, Chau and Yip7,Reference Yip, Cheung, Chau and Law8 Studies have confirmed that fear of COVID-19 acts as a mediator to increase psychological events such as depression and anxiety,Reference Mahmud, Talukder and Rahman2 thereby making individuals psychologically vulnerable to suicidality.Reference Mamun9 Thus, increments in suicide rates have been seen owing to burdens related to fear of COVID-19, as well as other devastating effects of the pandemic (see MamunReference Mamun9 a systematic review of studies on suicide in Bangladesh).

For understanding the effects of fear of COVID-19 on people and adopting effective mental health strategies, there is a need for epidemiological studies.Reference al Mamun, Hosen, Misti, Kaggwa and Mamun10,Reference Hossain, Rahman, Trisha, Tasnim, Nuzhath and Hasan11 However, there has been a lack of studies assessing fear of COVID-19 compared with other aspects of mental suffering, including depression, anxiety and stress, in Bangladesh.Reference Hossain, Rahman, Trisha, Tasnim, Nuzhath and Hasan11 To the best of the author's knowledge, three studies have assessed risk factors for fear of COVID-19 across different cohorts (i.e., the general population,Reference Hossain, Hossain, Walton, Uddin, Haque and Kabir12 the general population and healthcare professionals,Reference Sakib, Akter, Zohra, Bhuiyan, Mamun and Griffiths4 and older adultsReference Mistry, Ali, Akther, Yadav and Harris13), whereas another study explored its mediating role in career anxiety among students.Reference Mahmud, Talukder and Rahman2 However, none of these studies considered such a large sample as that used in the present study, provided any predictive models explaining the fear of COVID-19, or considered its nationwide spatial distribution.

More engagement with COVID-19-preventive behaviours is frequently observed in individuals with higher COVID-19 fear,Reference Harper, Satchell, Fido and Latzman14 where fear of COVID-19 acts as a motivational factor.Reference Pakpour and Griffiths15 Whereas, practice of behaviours related to COVID-19 knowledge, fear and so on, increase among female individuals and those with higher education levels.Reference Islam, Safiq, Bodrud-Doza and Mamun16–Reference Al-Hanawi, Angawi, Alshareef, Qattan, Helmy and Abudawood18 However, none of the aforementioned Bangladeshi studies considered the associations of education level or gender with fear of COVID-19; these associations are investigated herein.

Method

Study procedure, participants and ethics

The present nationwide cross-sectional study was conducted during the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, between 1 and 10 April 2020. The survey was conducted via online promotion; three or four research assistants from each of the 64 districts in Bangladesh were employed to facilitate access to the survey link through their social media platforms. The research team approached nearly 11 000 participants; 10 067 were enrolled in the present study after meeting the criteria of being Bangladeshi residents aged over ten years. Ethical approval for this project was obtained from two Bangladeshi institutes (see Ethics statement). For detailed information about the study sample, procedures, participants, ethics and data access, please refer to the following publications.Reference Pakpour, Al Mamun, Hosen, Griffiths and Mamun19–Reference Sakib, Bhuiyan, Hossain, al Mamun, Hosen and Abdullah23

Measures

Independent variable

Information related to basic sociodemographic variables including age, gender, education level, occupation status, marital status, current residence type and district of residence was collected in this study. Education level was categorised into two types: lower education (up to secondary high school) and higher education (tertiary education). Behaviour- and health-related variables (smoking status, perceived health status [based on a Likert scale], social media use, etc.) were also included in this study. Participants were asked whether anyone had returned to their home from Dhaka or outside the Bangladesh area/country which were highly affected by COVID-19. Finally, sources of COVID-19-related information (social media, newspaper, television, YouTube, etc.) were also assessed.

Dependent variable

Fear of COVID-19 was assessed using the Bangla Fear of COVID-19 Scale,Reference Sakib, Bhuiyan, Hossain, al Mamun, Hosen and Abdullah23 which was considered the dependent variable. Bangla Fear of COVID-19 Scale was adapted and validated from the English version of the scale originally developed by Ahorsu et al.Reference Ahorsu, Lin, Imani, Saffari, Griffiths and Pakpour24 The screening tool comprises a total of seven items (e.g., ‘I am afraid of losing my life because of coronavirus-19’), and responses are recorded on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The score ranges between 7 to 35, where a higher score indicates greater fear of COVID-19. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha was very good (0.88).

Statistical analysis

Of the 10 067 respondents, data for 10 052 participants were finally analysed after exclusion of 15 transgender individuals (because of a low response rate). Data were analysed using SPSS 23.0 for descriptive statistics and regression models. Independent t-tests and analysis of variance were performed to determine the associations between the studied variables and fear of COVID-19 (as a dependent variable). Hierarchical linear regression was used to observe the independent variables’ contributions to fear of COVID-19. The normality of the distributions (e.g., skewness and kurtosis values) and multicollinearity (e.g., variance inflation factor and tolerance values) were also tested, and no issues were observed. P < 0.05 was set as statistically significant with 95% confidence intervals. Also, gender-based and education-level-based post hoc analyses were performed for all tests. Finally, ArcGIS 10.8 was used to examine the nationwide distribution of fear of COVID-19 and its relationship with COVID-19 cases, gender and education level across districts.

Ethics statement

Ethical permission to conduct this study was granted by the Biosafety, Biosecurity and Ethical Committee of Jahangirnagar University, Bangladesh (BBEC, JU/M 2O20/COVlD-l9/(9)2), and the Institute of Allergy and Clinical Immunology of Bangladesh ethics board, Bangladesh (IRBIACIB/CEC/03202005).

Consent statement

All participants provided online informed consent prior to starting the survey. They were informed about the purpose and nature of the study, and they had the right to withdraw their data if they wanted to. For participants less than 18 years old, parental consent was obtained. All participants were assured about the confidentiality of their data.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

Of the total of 10 052 participants, the majority were male (56.2%, n = 5650), highly educated (80.8%, n = 8127), students (58.4%) and single with respect to marital status (70.3%), and 40.1% resided in the divisional city. About 71.3% were aged 20 to 29 years, and the mean age of the total sample was 26.95 ± 9.632 years (Table 1). About 14.7% were smokers, 2.6% reported consuming alcohol, 24.6% had a chronic disease and 90.9% used social media (Table 2). Approximately 12.9% and 2.5% of the participants reported that someone had returned to their home from the COVID-19 high-risk region Dhaka and from a foreign country, respectively. Of the COVID-19 information sources, social media was prominently reported as being used (Table 3).

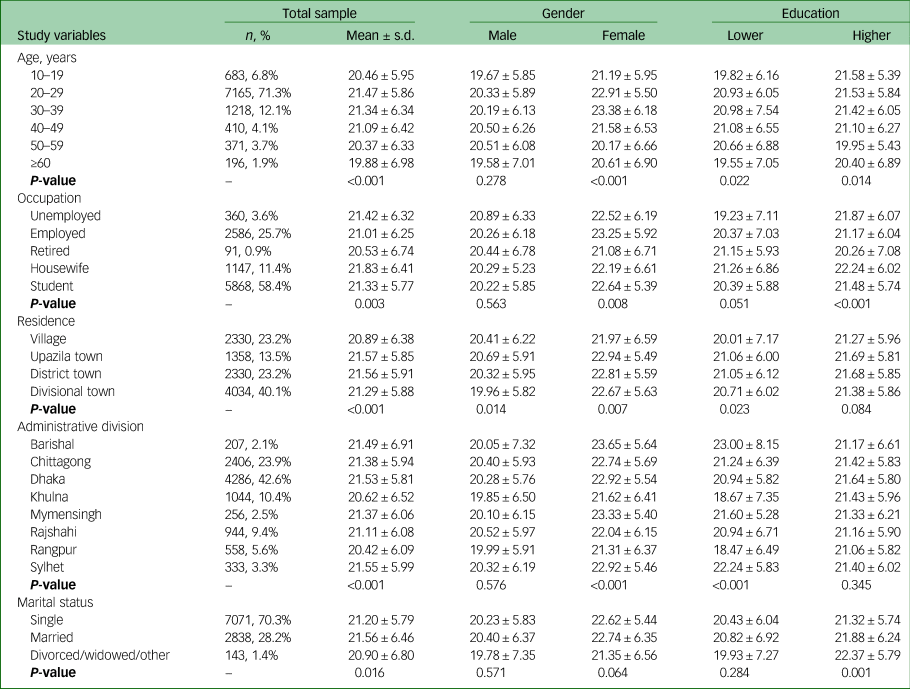

Table 1 Distribution of fear of COVID-19 scores across sociodemographic variables

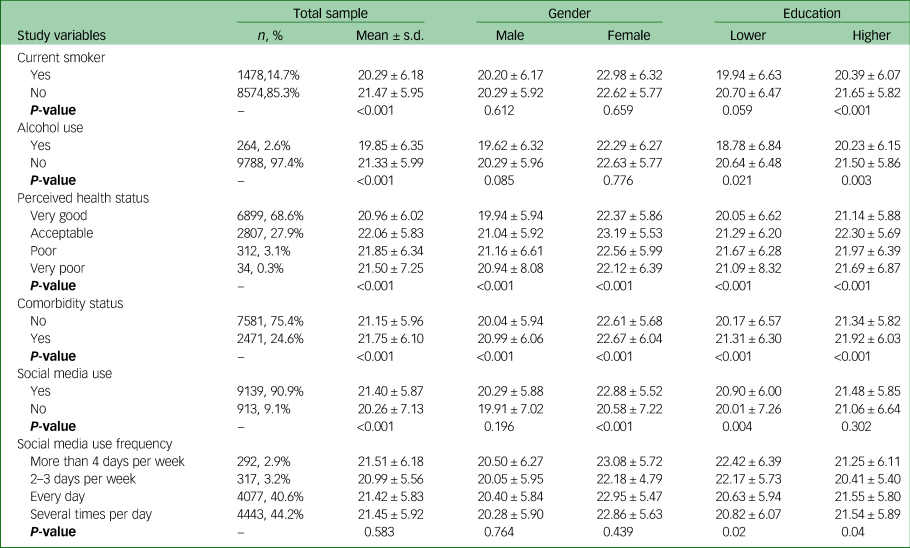

Table 2 Distribution of fear of COVID-19 scores across behaviour- and health-related variables

Table 3 Distribution of fear of COVID-19 scores across the COVID-19-related variables

Distribution of fear of COVID-19 scores

The overall mean score for fear of COVID-19 was 21.30 ± 6.01. The distribution of COVID-19 fear scores across sociodemographic variables is presented in Table 1; all of the associations were statistically significant. Female participants had higher fear of COVID-19 scores compared with their male counterparts (22.62 ± 5.78 v. 20.27 ± 5.98; t = −19.913, P < 0.001), and highly educated participants reported higher fear of COVID-19 than less educated ones (21.47 ± 5.87 v. 20.58 ± 6.50; t = −5.856, P < 0.001). Participants being smokers and consuming alcohol had lower scores for COVID-19 fear, whereas higher scores were found for participants with chronic diseases and those who were social media users (Table 2). Of the COVID-19-related variables, participants who used social media as a source of COVID-19 information had higher fear of COVID-19 scores (21.52 ± 5.86 v. 20.27 ± 6.55; P < 0.001), whereas lower scores were found for those who read newspapers for COVID-19 information (21.13 ± 5.97 v. 21.46 ± 6.04; P = 0.005) (Table 3). Gender-based and education-level-based distributions of fear of COVID-19 scores are presented in Tables 1–3.

Predictive factors of fear of COVID-19

The results of the hierarchical linear regression analysis of factors predicting fear of COVID-19 are presented in Table 4 (total sample), Supplementary Table 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.984 (gender-based) and Supplementary Table 2 (education-level-based). However, sociodemographic variables were included in model 1, whereas in model 2, behaviour- and health-related factors were compiled with sociodemographic variables. Finally, COVID-19-related variables were included in model 3 with the variables entered in model 2. All of the models were statistically significant. A 5.1% variance of fear of COVID-19 scores was predicted in the total sample; this increased to 5.7% and 6.2% in model 2 and model 3, respectively. The gender-based and education-level-based explanatory power of fear of COVID-19 can be found in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The final gender-based hierarchical regression model explained 2% and 1.9% of the variance in predicted fear of COVID-19 for males and females, respectively (Supplementary Table 1), whereas 4.7% and 6.7% of the variance were explained in the final education-level model for lower and higher education levels, respectively (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 4 Hierarchical regression analysis of factors predicting fear of COVID-19

B, unstandardised regression coefficient; β, standardised regression coefficient; SBHF, someone has returned home from; SCI, source of COVID-19 information.

a. 1 = Male, 2 = Female.

b. 1 = Lower, 2 = Higher.

c. 1 = Unemployed, 2 = Employed, 3 = Retried, 4 = Housewife, 5 = Student.

d. 1 = Village, 2 = Upzilla town, 3 = District-level town, 4 = Divisional city.

e. 1 = Barishal, 2 = Chittagong, 3 = Dhaka, 4 = Khulna, 5 = Mymensingh, 6 = Rajshahi, 7 = Rangpur, 8 = Sylhet.

f. 1 = Single, 2 = Married, 3 = Divorced/widowed/other.

g. 1 = Yes, 2 = No.

h. 1 = Very good, 2 = Acceptable, 3 = Poor, 4 = Very poor.

i. 1 = No, 2 = Yes.

j. 1 = More than 4 days per week, 2 = 2–3 days per week, 3 = every day, 4 = several times per day.

District-wise distribution of fear of COVID-19

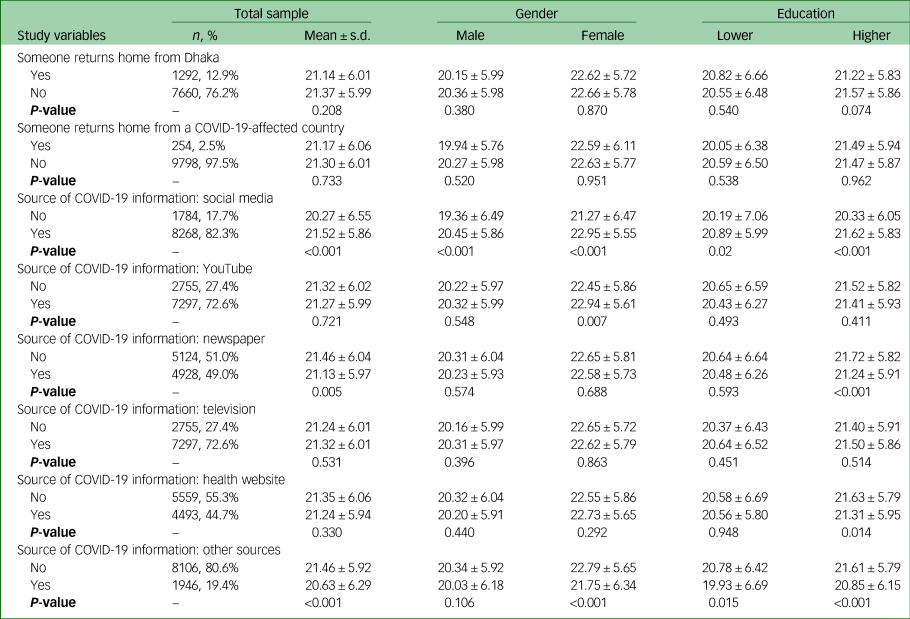

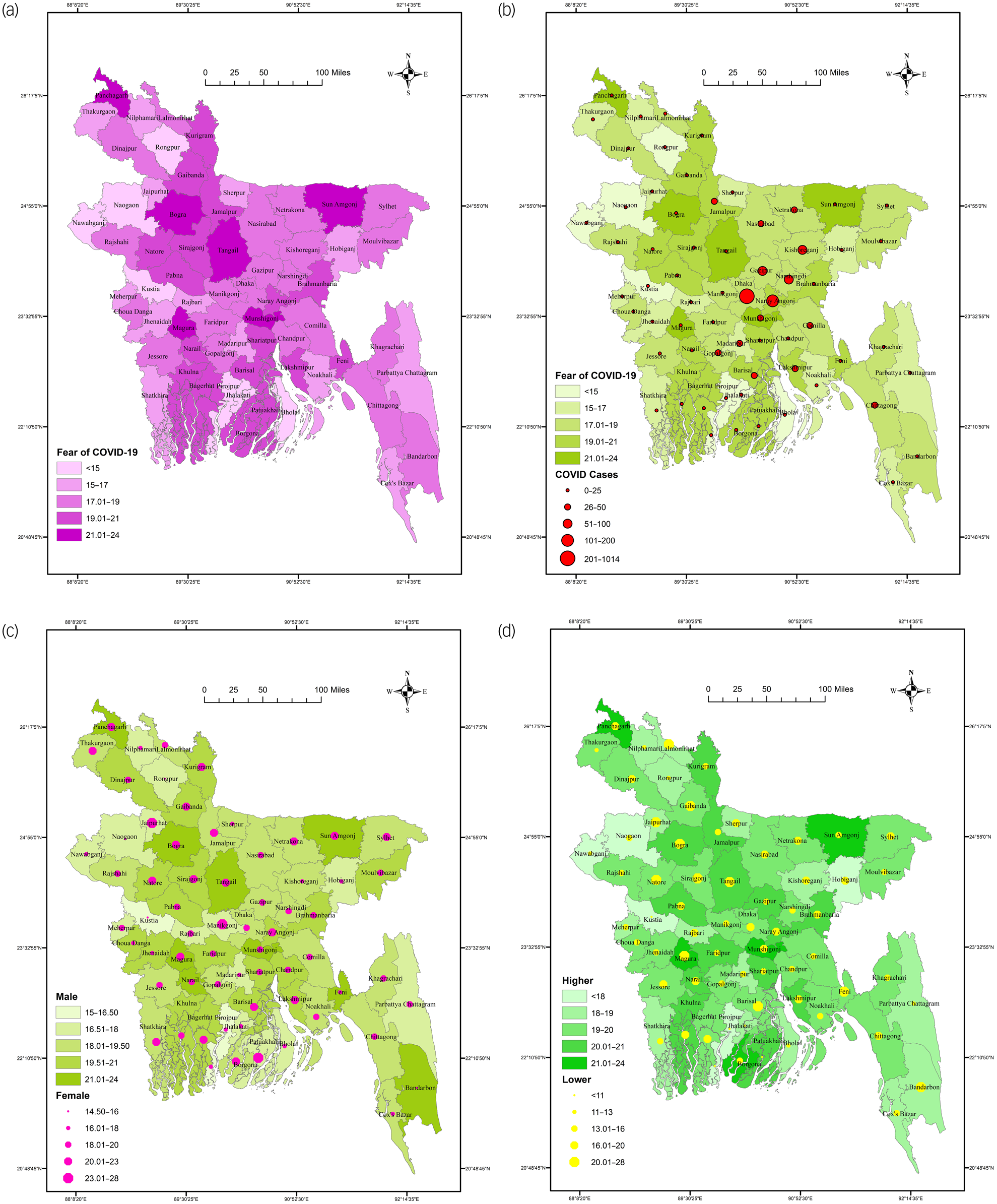

District-wise spatial distribution of fear of COVID-19 is presented in Fig. 1(a) and was statistically significant (F = 5.897, P < 0.001). Higher levels of fear of COVID-19 were found in Magura, Panchagarh, Tangail, Sunamganj, Munshiganj, Bogra, Barguna, Narail and Naraynganj; by contrast, Kushtia, Pirojpur, Chapainawabganj, Jhalokathi, Naogaon and Rangpur districts had lower fear of COVID-19.

Fig. 1 (a) Distribution of fear of COVID-19 across districts in Bangladesh. (b) Distribution of fear of COVID-19 and COVID-19 cases across districts. (c) Gender-based distribution of fear of COVID-19 across districts. (d) Education-level-based distribution of fear of COVID-19 across districts.

District-wise relationship of fear of COVID-19 with COVID-19 cases

Figure 1(b) represents the relationship of fear of COVID-19 with numbers of COVID-19 cases in the respective districts. However, fear of COVID-19 and COVID-19 cases were heterogeneously distributed across the districts; that is, no consistent association of higher COVID-19 cases with higher fear of COVID-19 was found.

District-wise distribution of gender-based fear of COVID-19

The gender-based distribution of fear of COVID-19 across districts is presented in Fig. 1(c); the associations of both genders with fear of COVID-19 were found to be statistically significant (F = 2.932, P < 0.001, and F = 4.415, P < 0.001 for males and females, respectively). Male participants from the districts of Magura, Munshiganj, Sunamganj, Bandarban, Feni, Tangail, Panchagarh and Bogra had higher fear of COVID-19 scores, as did female participants from Patuakhali, Joypurhat, Manikganj, Lakshmipur, Panchagarh,Barishal, Tangail and Barguna. However, both genders from the districts of Panchagarh, Bogra, Tangail and Sunamganj reported higher fear of COVID-19.

District-wise distribution of education-level-based fear of COVID-19

The education-level-based distribution of fear of COVID-19 across districts is presented in Fig. 1(d); the associations of both education levels with fear of COVID-19 were found to be statistically significant (F = 6.226, P < 0.001, and F = 1.773, P < 0.001 for lower education and higher education, respectively). Participants with lower education from the districts of Lalmonirhat, Barishal, Bandarban, Tangail, Sirajganj, Magura, Bogra, Natore and Gaibandha had higher fear of COVID-19 scores, compared with those from Sunamganj, Panchagarh, Magura, Munshiganj, Barguna Naraynganj, Tangail, Kurigram and Shariatpur for more highly educated participants. However, participants of both education levels from the districts of Tangail, Magura, Bogra and Gaibandha had higher fear of COVID-19 scores.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic is a public health threat that can increase peoples’ psychological risk and vulnerability by intensifying mental health stressors including fear, panic and uncertainty. Furthermore, the unexpected fear of COVID-19 can be life-threatening by leading to a drastic decision such as suicide.Reference Dsouza, Quadros, Hyderabadwala and Mamun5–Reference Yip, Cheung, Chau and Law8 Therefore, identifying the factors associated with fear of COVID-19 can help with the adoption and implementation of a better mental health strategy. Herein, factors related to fear of COVID-19 were identified from a nationwide sample collected by an online survey during the first wave of the pandemic in Bangladesh. The sample was limited owing to the use of an online survey with responses overwhelmingly from educated individuals; therefore, a post hoc analysis considering participants’ education levels was conducted. This was the first attempt to present a GIS-based distribution of fear of COVID-19 across the administrative districts of the country.

The overall mean fear of COVID-19 score was 21.30 ± 6.01 (out of a possible of 35) in the present sample. Use of the same instrument to assess levels of fear of COVID-19 has been reported in other Bangladeshi studies. For example, a mean score of 18.53 ± 5.013 was reported for a survey conducted from April to May 2020 in a sample of 2157 individuals,Reference Hossain, Hossain, Walton, Uddin, Haque and Kabir12 and 19.4 ± 6.1 in another study comprising a total of 1032 elderly individuals conducted in October 2020.Reference Mistry, Ali, Akther, Yadav and Harris13 Thus, the present sample showed higher fear of COVID-19 scores, although comparisons were limited because of the study implementation time and lack of representativeness of samples across these Bangladeshi studies.

The study found female gender to be a risk factor for reporting higher fear of COVID-19; similarly, gender was identified as one of the significant predictors of fear of COVID-19 in other Bangladeshi studies.Reference Sakib, Akter, Zohra, Bhuiyan, Mamun and Griffiths4,Reference Hossain, Hossain, Walton, Uddin, Haque and Kabir12,Reference Mistry, Ali, Akther, Yadav and Harris13 Reckless and irresponsible attitudes towards COVID-19 are more frequently observed among male participants, indicating that females are more conscious of preventive COVID-19 behaviours, leading to higher fear of COVID-19.Reference Islam, Safiq, Bodrud-Doza and Mamun16 Similarly, the level of consciousness increases with higher levels of educational attainment. That is, more educated individuals are at risk of higher fear of COVID-19 owing to the avoidance behaviours they adopt to protect themselves from potential virus infection,Reference Islam, Safiq, Bodrud-Doza and Mamun16–Reference Al-Hanawi, Angawi, Alshareef, Qattan, Helmy and Abudawood18 which is also reported in the study.

The studied variables predicted the explanatory power of the fear of COVID-19 in this study. Initially, sociodemographic variables (i.e., age, gender, education, occupation, residence, administrative division and marital status) predicted a 5.1% variance in fear of COVID-19. When behaviour- and health-related factors (i.e., smoking status, alcohol consumption, perceived health status, comorbidity status, social media use and frequency of social media use) were included, together with sociodemographic variables, the variance in fear of COVID-19 increased to 5.7%. Finally, after adjusting for COVID-19-related variables, an additional 0.5% of explanatory power was obtained. As this was an exploratory study, comparisons of the present models with those of prior studies were limited. However, it is anticipated that these models will help to facilitate further investigations.

The GIS-based distribution-related all of the associations with fear of COVID-19 were statistically significant. Higher fear of COVID-19 was found in the districts of Magura, Panchagarh, Tangail, Sunamganj, Munshiganj, Bogra, Barguna, Narail and Naraynganj. However, with respect to the relationship between COVID-19 fear and numbers of COVID-19 cases across districts, a heterogeneous distribution was found; that is, there was no consistent relationship between higher or lower COVID-19 case numbers with higher or lower fear of COVID-19. The districts of Panchagarh, Bogra, Tangail and Sunamganj reported higher fear of COVID-19 for both genders, although there were distinct districts reporting higher COVID-19 fear for each gender. Similarly, the districts of Tangail, Magura, Bogra and Gaibandha had higher fear of COVID-19 scores for participants of both education levels.

Several methodological issues of the present study should be noted as limitations. First, it was a cross-sectional study; this may hinder the ability to infer causal associations from the current findings. Online surveys can be limited by selection bias (e.g., the overwhelming response from educated persons). Moreover, important behavioural predictors influencing the level of fear of COVID-19 (perceived behavioural control, action self-efficacy, etc.) were not considered in this study.Reference Lin, Imani, Majd, Ghasemi, Griffiths and Hamilton25 However, despite these limitations, this study provides baseline information across districts on an important but unexplored issue, fear of COVID-19, in the context of Bangladesh.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.984.

Data availability

The data used in this study can be accessed at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2020.106621.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks all the participants and research assistants, without whom this self-funded study could not have been implemented. It should also be noted that the author's affiliation, the CHINTA Research Bangladesh, was formerly known as the Undergraduate Research Organisation.

Funding

None.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.