There is a growing awareness that strengthening mental health systems to effectively prevent mental ill health and care for people with mental health problems requires a broad perspective, taking into account the interconnectedness of human and financial resources beyond diagnosis and provision of treatment. Most mental health-related capacity building in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) focuses on training clinicians and/or lay people to identify and treat people who need care to reduce the treatment gap. However, health system change also relies on support from other key stakeholders to achieve comprehensive improvements. Three stakeholder groups are particularly crucial, but are rarely considered, as target groups for strengthening mental health systems in LMICs: (a) service users and caregivers; (b) policymakers and planners; and (c) mental health researchers. In general, health policy and health systems research in relation to mental health in LMICs is a neglected field.Reference Mills1 Improvements of mental health systems and hence mental health outcomes require commitment and understanding from policymakers and planners to allocate and coordinate budgets appropriately, and to plan for appropriate and inclusive local and national policies. A critical consideration is having insights from service users and caregivers communicated effectively, to ensure that any system or policy reform is appropriate and relevant to their needs and preferences.Reference Samudre, Shidhaye, Ahuja, Nanda, Khan and Evans-Lacko2–Reference Gurung, Upadhyaya, Magar, Giri, Hanlon and Jordans4 To facilitate this cycle, we need advocates and practitioners who are knowledgeable and equipped with real-world evidence about how to design a system that effectively addresses the mental health needs of the consumers in an equitable manner and operates efficiently within the available resources.

Mental health researchers also play a key role in developing and communicating needed evidence to these stakeholders. Although there are good models for researcher development,Reference Schneider, Sorsdahl, Mayston, Ahrens, Chibanda and Fekadu5 capacity and evidence are lacking in many LMICs. Two systematic reviewsReference Keynejad, Semrau, Toynbee, Evans-Lacko, Lund and Gureje6,Reference Semrau, Lempp, Keynejad, Evans-Lacko, Mugisha and Raja7 have clearly highlighted the paucity of evidence, first in relation to building the capacity of policymakers and planners to strengthen mental health systems in LMICs and second involving service users with mental health needs and their caregivers in health policy planning, service monitoring and research. The goal of this study was therefore to evaluate capacity-building activities carried out as part of the Emerald (Emerging mental health systems in low- and middle-income countries) project. These activities targeted three groups: (a) service users and caregivers; (b) policymakers and planners; and (c) mental health researchers. Emerald is a multicountry initiative to develop evidence and capacity for mental health system strengthening in Ethiopia, India, Nepal, Nigeria, South Africa and Uganda.Reference Semrau, Evans-Lacko, Alem, Ayuso-Mateos, Chisholm and Gureje8 In this paper we present the engagement and participation of each stakeholder group; changes in relevant mental health system knowledge; and overarching structural and institutional changes in research capacity.

Method

Emerald capacity-building activities

Details regarding Emerald capacity-building activities are reported in detail elsewhere.Reference Semrau, Evans-Lacko, Alem, Ayuso-Mateos, Chisholm and Gureje8–Reference Semrau, Alem, Abdulmalik, Docrat, Evans-Lacko and Gureje10 Briefly, a range of targeted activities were delivered in each of the six Emerald participating countries. Activities were tailored to local needs, context and resources and according to the target group.Reference Semrau, Alem, Abdulmalik, Docrat, Evans-Lacko and Gureje10

Service users and caregivers

For service users and caregivers (Table 1), the primary activity was a 1- to 3-day workshop to raise awareness about treatment and the rights of people with mental illness and to increase advocacy and involvement among service users and caregivers. (Training manuals developed for Emerald are included in supplementary Appendices 1A and 1B available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.14.) As part of the Emerald programme, efforts were also made to train primary care workers and managers to support service user involvement and to encourage PhD students to develop research in the area.

Table 1 Tailoring of the service users and caregivers short-course delivery and target participants to country context

Policymakers and planners

For policymakers and planners (Table 2), workshops in mental health system strengthening were run, with country teams selecting modules from the following domains: mental health awareness-raising, the chronic care model and mental health system planning. Each site also developed and maintained an ongoing dialogue with policymakers, providing technical support and facilitating collaboration between researchers and policymakers. As it was not possible to run workshops in Nepal, only engagement activities described in Table 2 were used for policymakers and planners. A course overview and materials are provided in supplementary Appendices 2A–C.

Table 2 Tailoring of the policymakers and planners short-course delivery and target participants to country context

Mental health researchers

To increase capacity among mental health researchers (Table 3), short courses were provided in mental health systems research, implementation science research and service user involvement in research in addition to further training about leadership and writing skills. A course overview and materials are provided in supplementary Appendices 3A–C. Ten PhD students were linked to Emerald and two MSc fellowships were offered on a competitive basis to individuals based in Emerald LMIC partner countries. PhD students also received support via a peer-led forum that was designed to bring PhD students together via a network to share information and experiences, and to identify needs and organise targeted e-learning opportunities delivered by members of the Emerald group.

Table 3 Tailoring of the mental health researchers short-course delivery and target participants to country context

Participants

As countries differed in their recruitment methods these are described separately for each country and each target group in the Appendix.

Assessment of capacity-building results

Evaluation of capacity-building activities covered a range of domains. Although the Emerald project collected qualitative and quantitative evaluation data,Reference Hanlon, Semrau, Alem, Abayneh, Abdulmalik and Docrat9 we focus on the quantitative findings here. Overall, the quantitative evaluation focused on process information and outcomes for each of the three target groups, in addition to agreed overarching indicators of structural or institutional change. Process information covered the absolute numbers of people who registered and completed each training module. To better understand the reach of the training, we collected information about participant characteristics such as gender, whether they were based in a public institution and whether they were from outside of the capital city.

To assess outcomes, participants were asked to complete a questionnaire before and after each training course/workshop. Questionnaires were tailored for each target group and covered participant satisfaction with the training and changes in knowledge (questionnaires are available on the Emerald website, see https://www.emerald-project.eu/home/). In terms of knowledge outcomes, we first examined the improvement in responses to knowledge items (averaged across items). We also assessed the total number of questions that demonstrated a positive pre–post improvement.

Change in institutional capacity was assessed in two ways. First, information was collected via questionnaire from MSc and PhD students, and early-career, mid-career and senior researchers about the impact of the Emerald programme on grant and paper involvement and international collaboration. Outputs (papers and grant participation) were collected in an identifiable email survey. All other feedback about, for example, satisfaction with the Emerald project were considered to be more sensitive and thus were collected anonymously via a GoogleForm document.

Second, senior researchers from each of the Emerald partner sites were also interviewed in relation to: (a) organisational self-sufficiency in delivering short courses, (b) how well equipped the department or institution was for the supervision of PhD students in the area of mental health systems research/implementation research (such as expertise, numbers of supervisors), (c) institutional capacity for delivering Masters-level training in health systems research, implementation science or non-communicable/long-term disorders and (d) the extent to which the Emerald programme contributed to any of these organisational changes and/or had become embedded in institutional training.

Research ethics committee approvals

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from King's College London, the World Health Organization and the institutional review boards of each of the participating sites.

Results

Process information

Almost all individuals who registered (94–100%) also attended the courses. The majority of participants in all stakeholder groups were men, although this was almost evenly split in the service user and caregiver workshop (55% men), whereas women were most clearly underrepresented in the policymakers and planners’ short course (87% men). There was a balanced representation from individuals living outside the capital city, in particular for the service user and caregiver workshops and the researcher course on service user and caregiver involvement, where approximately two-thirds of participants came from outside of the capital city. Most short-course participants were working in the public sector (65–87%), except for the service users and caregiver workshop where only 7% who attended were working in the public sector (Table 4).

Table 4 Process information and participant details for the researcher, policymaker/planner and service user/caregiver short courses

Capacity-building satisfaction outcomes

Table 5 shows that high levels of satisfaction were reported for the short courses across all three target groups. Policymakers and planners reported the highest level of satisfaction with 78% strongly agreeing (22% agreeing) that the teaching standard was high and 89% strongly agreeing (11% agreeing) that their expectations had been fulfilled. For all satisfaction outcomes, at least 95% of respondents reported agreement or strong agreement that they were satisfied with the standard of teaching and that their expectations had been fulfilled.

Table 5 Satisfaction and knowledge outcomes for researchers, policymakers/planners and service users/caregivers across all countries

Knowledge outcomes

On average, there was an improvement in knowledge across all short courses, with the greatest improvement in the researcher course on service user involvement in research (with a mean improvement in knowledge of 52.3% across items) and the lowest level of improvement in the researcher short course on implementation science (improvement of 1.8%). At the individual-item level, all short courses except for the researcher short course on implementation science showed an improvement in each item. See Table 5.

Overarching indicators of structural or institutional change

Emerald researchers and MSc/PhD students surveys

Almost all Emerald MSc/PhD students completed the email and online surveys (91%, n = 10), and 67% (n = 20) and 53% (n = 16) of Emerald researchers completed the anonymous online and email surveys, respectively. Among those who responded, all Emerald researchers and MSc/ PhD students attended at least one of the seven Emerald annual meetings in person, with the vast majority finding the meetings at least somewhat useful. In terms of MSc/PhD student supervision, all students reported being at least somewhat satisfied with the quality of supervision.

Over half (60%, n = 6) of participants of the MSc/PhD online survey reported having been involved in the early career research support group, with half (50%, n = 5) saying that they had found these meetings somewhat useful and half (50%, n = 5) saying that they had not found it useful. There seemed to be good cross-partner interaction between Emerald researchers with the majority of early-, mid- and senior career researchers reporting a lot or quite a lot of input from Emerald researchers outside their country. In terms of future career plans, 70% (n = 7) of MSc/PhD respondents said they felt somewhat equipped for their future career plans, and 30% (n = 3) said they felt very equipped. In total, 80% (n = 8) reported that their PhD or MSc had contributed ‘quite a lot’, and 20% (n = 2) ‘a lot’, to them feeling equipped for their future career plans. All ten MSc/PhD respondents reported that they planned to continue working in research, with all of them saying that Emerald had prepared them well to continue working within research either ‘a lot’ (40%, n = 4) or ‘quite a lot’ (60%, n = 6).

In relation to outputs, participants of the PhD email survey had submitted 1.25 papers on average relating to their PhD work (a total of 10, range 0–4) and a further 27 papers were planned (per person mean of 3.38; range 2–5). PhD respondents were also involved in 1.75 grant applications, on average, during their PhD (range: 0–4). Of 14 applications, 43% (n = 6) were successful. Participants of the researcher email survey reported an average of 5.8 paper submissions related to Emerald (range 0–16). In terms of grant applications, the researchers reported involvement in an average of 4.1 applications during Emerald (range: 0–10). Of these, 45% were successful (Table 6).

Table 6 Anonymous online capacity-building survey results of Emerald researchers and PhD students

NA, not applicable.

a. PhD students only.

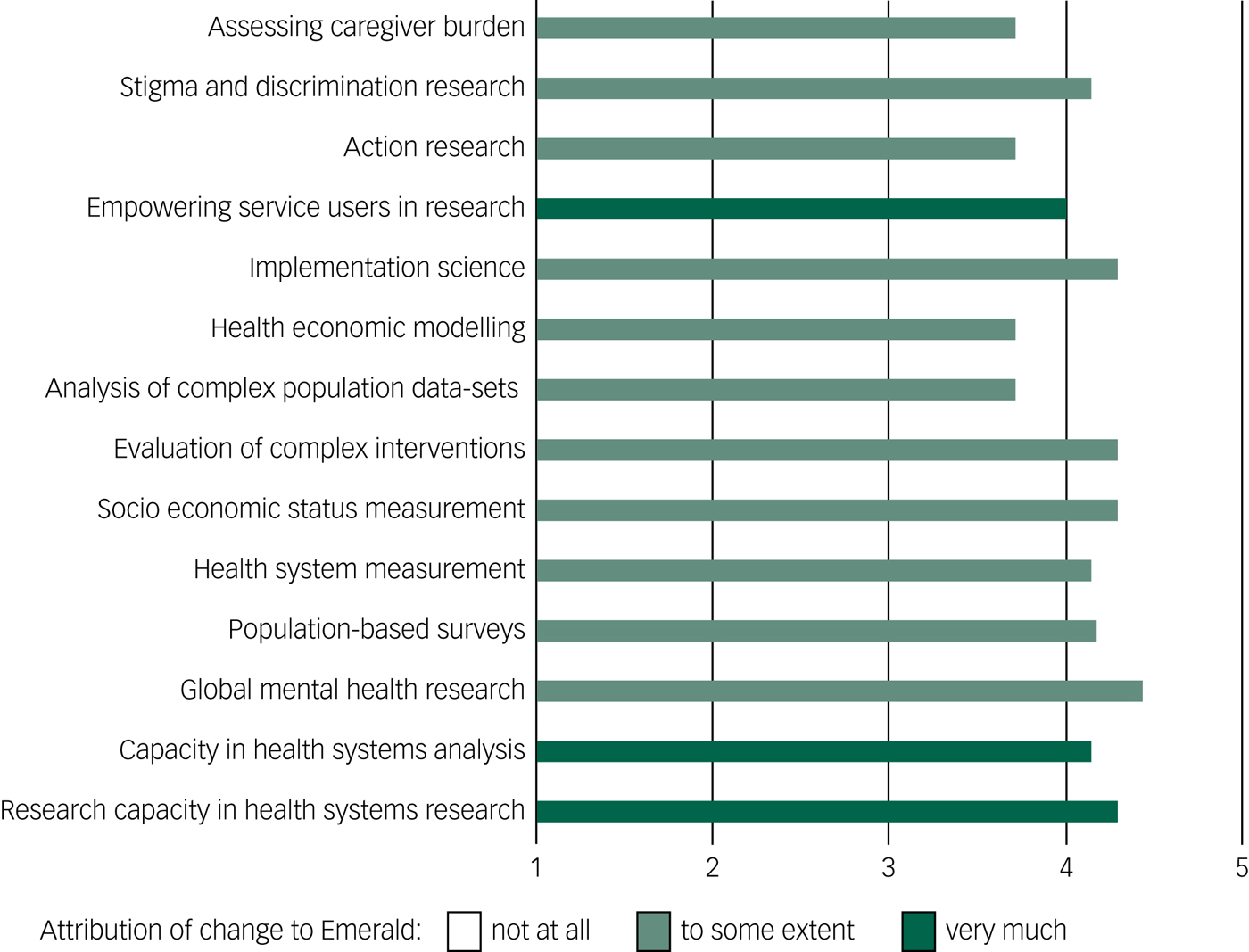

Changes in institutional research capacity

All Emerald LMIC partners experienced improvement in their capacity to conduct health systems research, with the change ‘very much’ attributed to Emerald by four institutional partners and ‘to some extent’ by the other three institutional partners. The average values across participating institutions of change in capacity and associated attribution to the Emerald programme are presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Change in capacity and attribution of change during Emerald project by research area, averaged across institutions.

Discussion

A total of 24 short courses involving 527 participants were implemented and evaluated for the target groups of service users and caregivers, policymakers and planners, and mental health researchers across the six Emerald countries. This was complemented by concerted training, including mentoring of junior researchers and development of resources to improve the research capacity of institutions associated with the Emerald project. Our evaluation suggested that short courses and workshops for each of the target groups were associated with high levels of satisfaction and led to improvements across target groups, although the implementation science module of the short course for researchers showed only a slight improvement. In relation to institutional capacity building, all of the Emerald LMIC partner institutions reported an increase in their research capacity for most aspects of mental health system strengthening and global mental health, and a large part of these positive changes were attributed to the Emerald programme.

The level of improvement varied across institutions and was lower where baseline capacity in the area was already strong. Developments in capacity were also reported by PhD students, MSc students and other Emerald researchers. Students and researchers reported being involved in publishing research papers, submitting grant applications and supervising students. These findings suggest that the Emerald model of delivering and evaluating tailored capacity-building activities could provide an important step towards strengthening the human resources for researchers needed to support improved mental health systems in six LMICs.

The Emerald project demonstrated several areas of improvement across the six participating countries; however, countries also differed widely in their baseline capacity, human, financial and political resources and needs; and thus, capacity-building strategies varied in each country. For example, Ethiopia had no service user organisations and only one caregiver organisation based in the capital city, whereas Uganda already had three service user organisations with 16 900 members spread throughout the country.Reference Lempp, Abayneh, Gurung, Kola, Abdulmalik and Evans-Lacko11 Country-level adaptations were made to all of the short courses, to fit in with the individual countries' local contexts and needs. This highlights the challenges in developing training materials that could be applicable across a diverse group of countries and the importance of training local facilitators to be sensitive to the group needs when delivering and facilitating the workshops. As a result, the level of appropriateness of training materials was diverse and required careful situation analysisReference Semrau, Evans-Lacko, Alem, Ayuso-Mateos, Chisholm and Gureje8 to ensure that the facilitator delivering the workshop had a good grasp of this context.

There were some areas of the capacity-building activities that need further attention. In particular, the implementation research course for researchers did not demonstrate improvements at the level shown in the other short courses. It may be that for this course the materials were being continuously developed while the evaluation was not modified alongside the development of the course materials. Sites noted that it was particularly useful to tailor the course to the country-specific context; however, some details such as those related to economic evaluation were limited given the lack of data and specific expertise in this area available in the participating countries.

Strengths and limitations

The findings from these capacity-building activities and their evaluation add to the sparse literature on capacity building and mental health system strengthening in LMICs, in particular for policymakers and planners, and service users and caregivers.Reference Keynejad, Semrau, Toynbee, Evans-Lacko, Lund and Gureje6, Reference Semrau, Lempp, Keynejad, Evans-Lacko, Mugisha and Raja7 There are, however, several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. In relation to the short courses, it was difficult to assess practice and/or the behavioural impacts as our evaluation used proxy indicators based on self-report. Self-report indicators may exaggerate the behavioural impact or change. In some contexts, it may be possible to supplement survey responses with analysis of publicly available documents of health system responses to community mental health needs to examine the impact on mental health system strengthening. However, the quality and comprehensiveness of public reports were not of high quality in the sites where Emerald activities were delivered. Additionally, it is difficult to know exactly how much of an impact could be attributed to the Emerald programme using these more general types of outcomes that are not precisely tied to Emerald.

Moreover, these broader system impacts may take time to become apparent and our evaluation timeline did not allow for a long-term follow-up to assess the impact of the short courses. Our evaluation of institutional research capacity did permit a longer-term follow-up by collecting information about subjective experiences and academic outputs and resources attributable to the 5-year Emerald project. We were not able to compare the impacts to a control group that did not receive the capacity-building activities and so it is difficult to know what kind of changes in institutional capacity would have resulted without Emerald. Nevertheless, our evaluation demonstrated a high level of productivity among associated researchers and institutions.

Implications and future directions

Evidence-based capacity-building is an important aspect of mental health system strengthening in LMICs. The Emerald project activities and evaluation have shown that building capacity in mental health system strengthening in LMICs is feasible and generally welcome by participants and beneficiaries. Focusing on three distinct and interrelated target groups of service users and caregivers, policymakers and planners, and mental health researchers also showed the potential for interaction between these groups. For example, equipping service users and caregivers with greater knowledge, awareness and receptiveness to mental health research and service planning could facilitate greater involvement in a synergistic way if policymakers, planners and researchers are also aware of the benefits of involving service users and caregivers. Similarly, building the capacity of mental health researchers could increase the evidence needed by policymakers and planners to improve the quality and efficiency of mental health service planning. In order to better understand the effects of capacity-building activities, potential synergies and areas needing improvement, evaluation needs to be an integral part of the delivery of these activities.

The evaluation framework used by the Emerald project might serve as a model for the assessment of capacity-building across the three selected target groups of stakeholders in LMICs. Although the starting point and appropriate strategies for this may vary across different countries, making training and evaluation materials freely and publicly available should further increase capacity and involvement in mental health system strengthening in the future.

Moreover, future evaluations of capacity-building activities can build and improve on the Emerald framework by, for example, considering applying triangulation techniques to assess the impact on a broader group of stakeholders and considering additional outcomes. We are currently piloting other evaluation methods at the local level that may strengthen our understanding of this process. For example, there is currently one Emerald linked PhD student in Ethiopia who is conducting in-depth action research to assess the impact of the capacity-building activities. In terms of specific measures, the Emerald programme also planned to incorporate an assessment of attitudinal changes among policymakers but the attitude questionnaires we developed were not acceptable to policymakers and planners.

Future evaluation frameworks should consider other ways of assessing attitudinal change and reduction in stigma, possibly using less direct proxies of this outcome. The Emerald project has made an important step to develop our understanding of the capacity-building process and further strengthening of mental health systems and increasing engagement of a range of stakeholders in this process will require us to continue to advance and improve on the delivery, implementation and evaluation of these activities. Short course and MSc module materials are openly available to facilitate capacity building.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement n° 305968; and the PRIME Research Programme Consortium, funded by the UK Department of International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries. No funding bodies had any role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the funders. G.T. is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) South London and by the NIHR Applied Research Centre (ARC) at King’s College London NHS Foundation Trust, and the NIHR Applied Research and the NIHR Asset Global Health Unit award. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. G.T. receives support from the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01MH100470 (Cobalt study). G.T. is supported by the UK Medical Research Council in relation the Emilia (MR/S001255/1) and Indigo Partnership (MR/R023697/1) awards. M.S. is supported through the NIHR Global Health Research Unit for Neglected Tropical Diseases at BSMS. S.E.-L. is supported by the European Research Council under the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ERC grant agreement n° (337673), Medical Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council and Global Challenges Research Fund. C.H. is supported by the PRogramme for Improving Mental health carE (PRIME), which is funded by the UK Department for International Development (DfID) (201446). The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the UK Government’s official policies. G.T., C.H., C.L., A.A. and I.P. are funded by the NIHR Global Health Research Unit on Health System Strengthening in Sub-Saharan Africa, King's College London (GHRU 16/136/54) using UK aid from the UK Government. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. C.H. additionally receives support from AMARI as part of the DELTAS Africa Initiative (DEL-15-01).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the short-course participants, trainers and mentors who took their time to support this project.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.14.

Appendix

Short course recruitment methods for each country and stakeholder group

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.