At present, drugs are not licensed specifically for the treatment of personality disorder.1,Reference Oldham, Gabbard, Goin, Gunderson, Soloff and Spiegel2 However, pharmacological treatment in clinical practice remains common.Reference Crawford, Kakad, Rendel, Mansour, Crugel and Liu3 Indeed, the majority of people with a personality disorder who attend secondary mental health services are prescribed psychotropic medication, often over extended time periods.Reference Baker-Glenn, Steels and Evans4 This is of concern for a number of reasons. Evidence suggests that psychotropic medication prescribing for this population is frequently outside licensed indications, and the recommended regular monitoring is not being done. Furthermore, multi-class psychotropic use has also been found to be common in this population.Reference Crawford, Kakad, Rendel, Mansour, Crugel and Liu3–Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg, Reich, Conkey and Fitzmaurice5 This is especially important given that polypharmacy is associated with physical health problems, such as weight gain, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, dyslipidaemia and prolonged QT and PR intervals,Reference Auquier, Lançon, Rouillon, Lader and Holmes6–Reference Suzuki, Ono, Tsuneyama, Sawamura, Sugai and Fukui8 and detrimental health outcomes, such as hospital readmissions and mortality.Reference Kadra, Stewart, Shetty, MacCabe, Chang and Kesserwani9,Reference Baandrup, Gasse, Jensen, Glenthoj, Nordentoft and Lublin10 Although there is little research into the factors influencing prescribing in this population, there is some evidence to suggest that patients with a personality disorder attending specialist services (including specialist personality disorder and psychological treatment) are less likely to be prescribed medication than those in receipt of general psychiatric care.Reference Crawford, Kakad, Rendel, Mansour, Crugel and Liu3 However, existing research has examined small samplesReference Crawford, Kakad, Rendel, Mansour, Crugel and Liu3,Reference Baker-Glenn, Steels and Evans4 and focused predominately on more common subtypes of personality disorder, such as emotionally unstable subtype.Reference Paton, Crawford, Bhatti, Patel and Barnes11,Reference Stoffers and Lieb12 The existence of an association between the receipt of prescribed psychotropic medication and attendance for psychological treatment among patients with personality disorder has not been previously investigated. It might be anticipated that specialist psychological treatment services may be more likely to adhere to national guidelines recommending that psychotropics are not routinely prescribed to people with personality disorder. Yet, to date, this has not been formally tested. The aim of this study was to start addressing this gap by examining psychotropic medication use among adults with a personality disorder who receive secondary mental healthcare, and to investigate whether this is reduced in patients seen by psychological treatment services.

Method

We carried out a retrospective cohort study, using South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLAM) secondary mental healthcare electronic records, accessed via the Clinical Record Interactive Search (CRIS). SLAM provides near-monopoly public mental health services for approximately 1.36 million residents across four London boroughs (Lambeth, Southwark, Lewisham and Croydon). CRIS was developed in 2008, and accesses de-identified electronic health records information for over 400 000 people in SLAM. The CRIS resource has been previously described in detail,Reference Stewart, Soremekun, Perera, Broadbent, Callard and Denis13,Reference Perera, Broadbent, Callard, Chang, Downs and Dutta14 and is approved by the Oxford Research Ethics Committee C (reference 08/H606/71 + 5) as a database for secondary analysis.

Using CRIS, we ascertained all patients aged ≥18 years who were in contact with SLAM mental health services between 1 August 2015 and 1 February 2016, and had received a diagnosis of a personality disorder (ICD-10Reference World Health Organization15 codes F60–F69) before the end of the observation period (1 August 2015 and 1 February 2016). For each patient, we determined the most recent personality disorder diagnosis before the end of the observation window, also referred to as index personality disorder diagnosis. We also determined whether patients had attended an Improving Access to Psychological Therapies service or secondary care specialist psychotherapy service, in the observation window.

The primary outcome was psychotropic medication use in the observation window. We considered all antipsychotic, benzodiazepine, antidepressant and mood stabiliser medications listed by the 65th edition of the British National Formulary.16 In instances where multiple medications from different categories were prescribed within a period of 6 months (but not necessarily simultaneously), this is referred to as multi-class psychotropic use. Psychotropic medication data were extracted from SLAM's pharmacy-dispensing database and from structured and free-text fields (using a natural language processing application) in the source health records accessed by CRIS. We have described the procedure for data extraction in detail in a separate publication.Reference Kadra, Stewart, Shetty, Jackson, Greenwood and Robert17

In addition, we investigated the sociodemographic, clinical and service use characteristics of all patients in our cohort. Age was calculated at the time of the index personality disorder diagnosis. The remaining sociodemographic factors were derived from the entry closest to 1 August 2015. Ethnic group categories were collapsed into ‘British’, ‘other White’, ‘Black Caribbean’, ‘Black African’, ‘Asian’ and ‘other’, because of small numbers in some cells. Clinical symptom presence/severity was estimated from the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS) completed closest to the index personality disorder diagnosis. HoNOS is a routinely administered clinical outcome instrument in British mental health services, and comprises 12 items designed to measure behaviour, impairment, symptoms and social functioning.Reference Wing, Beevor, Curtis, Park, Hadden and Burns18 Items are scored on a scale of 0 (no problem) to 4 (severe to very severe problem). Because of small cell sizes, subscale scores were collapsed into three categories: 0, ‘not a problem’; 1, ‘minor problem requiring no action’; and 2–4, ‘significant problem’. In addition, we determined the nature of any serious mental illness diagnosis (ICD-10 codes F20, F25 and F31) recorded closest to the index personality disorder diagnosis, and whether the patients had ever received a diagnosis of depression (ICD-10 codes F32 and F33), anxiety (ICD-10 codes F40–42), post-traumatic stress disorder (ICD-10 code F43), alcohol use disorder (ICD-10 code F10) or substance use disorder (ICD-10 codes F11, F12 and F14). The presence or not of any in-patient mental healthcare at any point during the observation window was further recorded.

Statistical analysis

Stata version 13 for Windows was used for all statistical analyses. We estimated the proportion of patients who had psychological therapies contact in the observation window, and examined the distribution of the sociodemographic, clinical and service use characteristics across the cohort. We further examined the prevalence of psychotropic medication use in all patients with a personality disorder diagnosis. Multivariable logistic regression models were built to examine the association between being seen by psychological therapies and receiving a psychotropic medication/s. Models were adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, comorbid serious mental illness diagnosis (ICD-10 codes F20, F25 and F31), in-patient stay during the observation window and HoNOS score.

Several sensitivity analyses were carried out. We first tested whether the timing of the HoNOS assessment had an effect on the association between psychological services contact and psychotropic prescription, by restricting the analyses to those with HoNOS scores within a year of the index personality disorder diagnosis. The principal reasoning for this was that we wanted to use the HoNOS score that was most reflective of the patient's functioning around the time of diagnosis. We further tested whether or not having a defined subtype of personality disorder had an effect on the association. In addition, we restricted the analysis to patients with an index personality disorder diagnosis within the past 2 years, to test whether this had an effect on the association. To address potential confounding by indication, we used a standard propensity score method, where the propensity score was the probability of receiving psychological service contact based on a model with all variables described above. The propensity scores were then used to identify patients whose scores indicated they have the potential to be seen or not seen by psychological therapies services in the observation period. In other words, those with extreme propensity scores (i.e. would always be likely to be seen by psychological services or never likely to be seen by psychological services) were excluded. We then constructed a fully adjusted logistic regression model, and restricted the analysis to patients with this restricted range of propensity scores. Finally, we conducted multivariable logistic regression analyses to examine the association between psychological services use and the prescription of multiple categories of psychotropic medications.

Results

We identified 3366 adults with a personality disorder who were receiving SLAM care between 1 August 2015 and 1 February 2016. Of these, 1057 (31.4%) did not have a specific personality disorder subtype indicated in their index diagnosis. Of the patients who had a subtype indicated, the most common were emotionally unstable (n = 1705, 50.7%) and dissocial (n = 155, 4.6%).

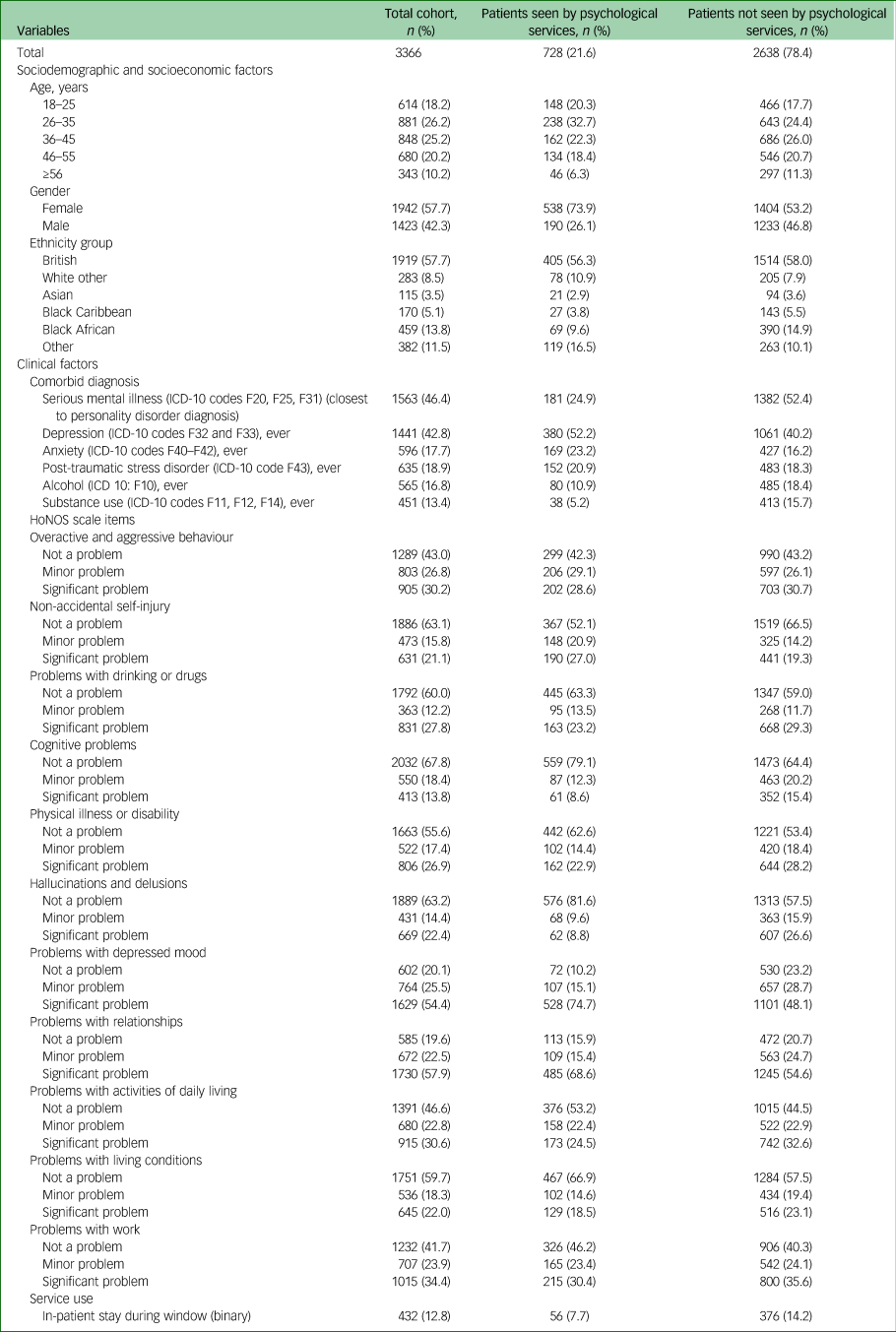

Of the sample, 728 (21.6%) patients received either Improving Access to Psychological Therapies service (n = 245, 7.3%) or specialist services contact (n = 548, 16.3%). Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the total cohort and by psychological services contact in the observation window. Overall, patients seen by psychological services were slightly younger, female, had a higher proportion of depression and anxiety, and more significant problems with non-accidental self-injury. Patients not seen by a psychological service had a higher proportion of ever receiving a comorbid diagnosis of serious mental illness, alcohol and/or substance use, and higher in-patient stay during the observation window.

Table 1 Cohort characteristics of patients with personality disorder diagnosis

HoNOS, Health of the Nation Outcome Scales.

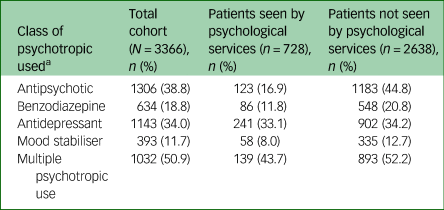

In total, 2029 (60.3%) patients were taking some form of psychotropic medication. Of these, 997 (49.1%) were prescribed only one psychotropic and 1032 (50.9%) had multi-class psychotropic use. Table 2 describes the prevalence of specific psychotropic medication categories across the cohort. Antipsychotics (38.8%) and antidepressants (33.9%) were the most commonly prescribed medications.

Table 2 Psychotropic medication use among patients diagnosed with personality disorder

a. Individual groups are not mutually exclusive.

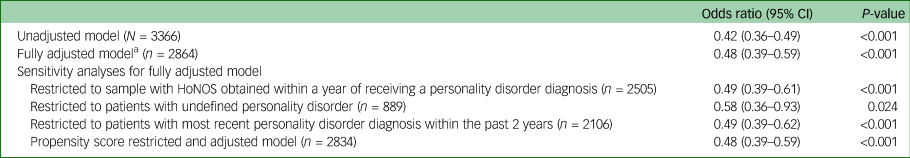

Table 3 summarises the multivariable logistic regression models for the association between receiving psychological therapies contact and being prescribed any psychotropic medication. In summary, patients in contact with psychological services were significantly less likely to be prescribed psychotropic medication. This association was sustained after adjusting for a number of sociodemographic, clinical and service use factors (odds ratio 0.48, 95% CI 0.39–0.59, P<0.001), and was further maintained following a propensity score-restricted (odds ratio 0.48, 95% CI 0.39–0.59, P<0.001) and adjusted analysis (odds ratio 0.47, 95% CI 0.39–0.56, P<0.001).

Table 3 Multivariable logistic regression analysis of the association between psychological services use and psychotropic medication prescribing

HoNOS, Health of the Nation Outcome Scales.

a. Model adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, comorbid serious mental illness diagnosis (ICD-10 codes F20, F25 and F31), in-patient stay during the observation window and HoNOS score.

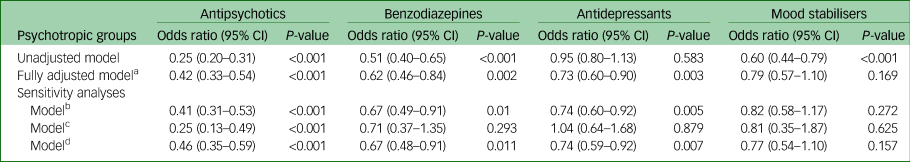

Table 4 summarises unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models, which examined the association between having contact with psychological therapies services and using different types of psychotropic medication. In the fully adjusted models, individuals in contact with psychological services were significantly less likely to use antipsychotics (odds ratio 0.42, 95% CI 0.33–0.54, P<0.001), benzodiazepines (odds ratio 0.62, 95% CI 0.46–0.84, P = 0.002) and antidepressants (odds ratio 0.73, 95% CI 0.60–0.90, P = 0.003). These associations were maintained after several sensitivity analyses, but no association was found with mood stabiliser use. Lastly, we found no significant association after adjustment between psychological service contact and receiving medications from multiple psychotropic categories (odds ratio 0.80, 95% CI 0.60–1.07, P = 0.133) (Supplementary Table 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.34).

Table 4 Multivariable logistic regression analysis of the association between psychological services use and different types of psychotropic medication prescribing (N=3366)

HoNOS, Health of the Nation Outcome Scales.

a. Model adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, comorbid serious mental illness diagnosis (ICD-10 codes F20, F25 and F31), in-patient stay during the observation window and HoNOS score.

b. Fully adjusted model where HoNOS was obtained within a year of receiving a personality disorder diagnosis.

c. Fully adjusted model where analysis was restricted to patients who did not have a defined personality disorder category.

d. Fully adjusted model where analysis was restricted to patients who have had their most recent personality disorder diagnosis within the past 2 years.

Discussion

In one of the largest observational studies of its kind, we examined recorded psychotropic medication prescribing in a cohort of patients diagnosed with personality disorder, and compared this between groups who did and did not use psychological services. Consistent with previous literature, the most commonly diagnosed personality disorder was the emotionally unstable type,Reference Paton, Crawford, Bhatti, Patel and Barnes11,Reference Coid, Yang, Yrer, Roberts and Ullrich19,Reference Cohen, Crawford, Johnson and Kasen20 the majority of the patients in the sample were receiving psychotropic medication from at least one class, just over a half were prescribed medications from two or more classes,Reference Baker-Glenn, Steels and Evans4,Reference Paton, Crawford, Bhatti, Patel and Barnes11 and antipsychotics and antidepressants were the most commonly prescribed medications.Reference Crawford, Kakad, Rendel, Mansour, Crugel and Liu3,Reference Baker-Glenn, Steels and Evans4,Reference Paton, Crawford, Bhatti, Patel and Barnes11

Patients with personality disorder who were using psychological services were slightly younger, had less comorbid serious mental illness, more comorbid depression and anxiety, and less functional problems, such as activities of daily living impairment and problems with living conditions and work. They also had lower in-patient stay during the observation window, compared with patients not seen by psychological services. In agreement with Crawford et al,Reference Crawford, Kakad, Rendel, Mansour, Crugel and Liu3 we found that patients who had contact with psychological services were less likely to be prescribed psychotropic medication in general, and more specifically, were less likely to receive antipsychotics, benzodiazepines and antidepressants. These associations remained largely unchanged after several sensitivity analyses. One possible explanation for these results could be that patients seen by psychological services are generally more stable, with fewer symptoms. However, we adjusted for severity of functional problems (as measured by HoNOS), and the presence of comorbid diagnoses, with little effect on the size of the associations. We also took account of confounding by indication, in other words the probability that medication prescription (or the reduction in this occurring) is a marker of other clinical features that are triggering referral to psychological services. To test for this possible explanation, we used a propensity score restriction and adjustment, and the results remained unchanged, suggesting that differences in the characteristics between the two groups could not explain why patients with psychological service contact were less likely to receive psychotropic medication. There is a need to understand factors that may influence psychotropic prescribing in this population. It is not known whether differences in psychotropic medication use reflect patient choice between medication and psychological treatment, or whether it is a function of service factors such as fewer prescribers in psychological treatment settings. Considering the observed differences from a service delivery perspective, it is not known whether medication is being withheld from a group of patients that could potentially benefit from it, or whether psychological treatment settings facilitate collaborative, judicious decision-making around medication use. Patient factors, such as lack of psychological mindedness and choosing not to engage in therapy, may preclude access to available psychological treatments,Reference Rueve and Correll21 and medication may provide an alternative therapeutic approach in general psychiatry settings. Patients with personality disorder may wish to take psychotropic medication to obtain immediate relief from symptoms such as paranoia, affective dysregulation or anxiety, and may resist attempts to reduce or stop medication. It has also been suggested that the act of prescribing constitutes a way of relating to patients, which may be reflective of the psychopathology of the conditionReference Martean and Evans22 such that the act of prescribing itself may symbolise a tangible act of care. In the absence of psychological treatment, there may be an expectation to prescribe for the purposes of providing such care and attenuating distress.

Similar to previous findings,Reference Crawford, Kakad, Rendel, Mansour, Crugel and Liu3 we found low mood stabiliser use in our cohort. Our results suggest that there was no difference in the likelihood of being prescribed mood stabilisers between the patients who were in contact with psychological services and those who were not. However, this lack of effect could have been a result of a lack of statistical power, given the infrequent use of mood stabilisers in the cohort overall. Given the teratogenicity of several mood stabilisers, avoidance of prescribing in women of childbearing age may account for the low use of mood stabilisers in the sample. Alternatively, the low level of mood stabiliser use could be because of the lack of consistent evidence to support their clinical efficacy for patients with personality disorder.Reference Crawford, Sanatinia, Barrett, Cunningham, Dale and Ganguli23 Consistent with previous research, we found that a high proportion of the patients in our sample had multi-class psychotropic useReference Zanarini, Frankenburg, Reich, Conkey and Fitzmaurice5,Reference Paton, Crawford, Bhatti, Patel and Barnes11 ; however, we found no difference in the risk of multi-class psychotropic use between patients who were receiving psychological service and those who were not. Therefore, our findings do not support previously proposed hypotheses that patients seen by psychological service are less likely to be offered medication treatment as a result of receiving alternative treatments.Reference Crawford, Kakad, Rendel, Mansour, Crugel and Liu3 An alternative hypothesis could be that patients who receive multi-class polypharmacy have either an inherently more severe personality disorder diagnosis or more severe comorbid mental disorders.

This study had several strengths. We examined a large and representative sample of patients seen by secondary mental health services. Although the sample was drawn from a single service provider, the heterogeneity of individual clinicians and teams are likely to outweigh any homogeneity imposed by the organisation, and our findings should be broadly reflective of real-world clinical practice in the UK.Reference Perera, Broadbent, Callard, Chang, Downs and Dutta14 Furthermore, utilising information available from de-identified electronic health records allowed us to identify and adjust for rich and diverse contextual information, reducing residual confounding. We further limited the effect of confounding by indication, through applying a propensity score method as a sensitivity analysis. However, several potential limitations also need to be considered. SLAM, like London, has a substantially higher proportion of minority ethnic groups, and higher presentation of people in both the lowest and highest socioeconomic groups, compared with England,Reference Perera, Broadbent, Callard, Chang, Downs and Dutta14 and this needs to be considered when drawing inferences. Although we adjusted for multiple confounders, it is possible that some residual confounding may have occurred. We were unable to measure factors such as duration of illness or stages of treatment as patients entered the observation period. Nor could we capture psychotropic prescribing reasons, which may have given information about possible mechanisms underlying our findings. Also, despite this being one of the largest observational studies in this filed, because of low numbers of certain personality disorder subtypes, we were unable to investigate medication use by personality disorder subtype. Nonetheless, our findings remain highly relevant as the field of personality disorder is moving toward the abandonment of subtypes of personality disorder and the retention of a single category of personality disorder.Reference Tyrer, Reed and Crawford24 Lastly, clinical symptoms were measured at one point in time. Capturing clinical symptoms over a period and examining changes over time could have provided a better understanding of how symptoms are related to medication use.

This study has important clinical implications. Improving the quality of psychotropic medication use in people with personality disorder is a clinical priority. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines1 currently provide no guidance, although there is a clear need for clinicians to be better supported in their decision-making. Although American Psychiatric Association guidelinesReference Oldham, Gabbard, Goin, Gunderson, Soloff and Spiegel2 provide some support in relation to emotionally unstable personality disorder, evidence that most prescribing does not clearly target comorbid conditionsReference Paton, Crawford, Bhatti, Patel and Barnes11 is important in considering their clinical utility. Development of formal guidance on conducting medication reviews for patients with personality disorder is needed to ensure appropriate and rational prescribing.

We suggest that the broad framework of medication optimisation, which provides a person-centred approach to the safe and effective use of medication by using the best available evidence to guide shared decision-making about treatment,Reference Tyrer, Reed and Crawford24 may support this aim. Medication review, a core part of a medication optimisation process, involving the structured and critical evaluation of prescribed medication, should be offered to all patients with personality disorder, including those in psychological treatment services.

There is also a need for clinical trials to ascertain the efficacy of psychotropic medication in this patient group. However, perhaps both more urgently and more practically, research in real-world clinical settings is needed to examine medication effectiveness. Efficacy studies with necessarily strict inclusion and exclusion criteria demand a degree of patient uniformity that is seldom seem in clinical practice, and the complexities of setting up efficacy studies mean that this is perhaps a longer-term goal. Research should not exclusively focus on emotionally unstable personality disorder given that almost half of the patients in our cohort had an undefined personality disorder or another subtype.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.34

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (G.K.-S.). The data are not publicly available due to the Information Governance framework and Research Ethics Committeeapproval in place concerning CRIS data use.

Author contributions

G.K.-S. and J.G. conceptualised and designed the study, carried out the data analysis and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. S.M., C.-K.C., M.F., R.D.H., P.M., H.S., A.H.Y. and R.S. contributed to study conceptualisation and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by the Clinical Record Interactive Search (CRIS) system funded and developed by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London, and a joint infrastructure grant from Guy's and St Thomas’ Charity and the Maudsley Charity (grant number BRC-2011–10035). R.S., H.S., R.D.H. and G.K.-S. receive salary support from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London, and R.S. is an NIHR Senior Investigator. P.M. receives salary support from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol. A.H.Y. is funded by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London, and is an NIHR Senior Investigator. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Declaration of interest

R.D.H., C.-K.C., H.S. and R.S. have received research funding from Roche, Pfizer, Janssen and Lundbeck. G.K.-S. has received funding from Janssen and Lundbeck. R.S. has also received research funding from Takeda. J.G.'s spouse is employed by AstraZeneca. A.H.Y. has received funding from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Sunovion, Servier, LivaNova, Janssen, Allegan, Bionomics, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma and COMPASS. S.M., M.F. and P.M. have no conflicts of interest to declare.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.