Severe mood and psychotic disorders (SMPD) are mental disorders that cause functional impairment and substantially interfere with one or more major life activities. These disorders often follow a chronic or recurrent course and available treatments have limited efficacy.Reference Cipriani, Furukawa, Salanti, Chaimani, Atkinson and Ogawa1–Reference Correll, Rubio and Kane4 Improving upon our ability to predict SMPD may be useful to inform targeted early interventions to prevent its onset.Reference Schultze-Lutter, Michel, Schmidt, Schimmelmann, Maric and Salokangas5 Recent research has shown that there is substantial overlap in the genetic and environmental contributors to various forms of SMPD.Reference Zwicker, Denovan-Wright and Uher6–Reference Caspi, Houts, Belsky, Goldman-Mellor, Harrington and Israel10 Consequently, it may be useful to identify overlapping, transdiagnostic predictors of mood and psychotic disorders that can be detected early enough to allow for preventive interventions. Self-experienced disruptions in thought, perception and other essential mental processes, referred to as basic symptoms, are potential early indicators of SMPD risk.Reference Schultze-Lutter and Theodoridou11

Basic symptoms and risk of mental illness

Basic symptoms may represent an early manifestation of mood and psychotic disorders, particularly psychotic illness.Reference Schultze-Lutter, Michel, Schmidt, Schimmelmann, Maric and Salokangas5,Reference Schultze-Lutter and Theodoridou11,Reference Schultze-Lutter, Ruhrmann, Fusar-Poli, Bechdolf and Klosterkötter12 Positive symptoms of psychosis include hallucinations and/or delusions, which are perceived by the affected individual as real experiences. In contrast to positive psychotic symptoms, basic symptoms are immediately recognised by the individual as abnormal disturbances to their typical thoughts, senses and feelings.Reference Schultze-Lutter13 These symptoms are often present years before the onset of illness and can be assessed in children as young as 8 years old.Reference Fux, Walger, Schimmelmann and Schultze-Lutter14 Basic symptoms have been examined in detail as a potential precursor to psychotic illness. Basic symptoms strongly predict the onset of psychotic illness.Reference Schultze-Lutter, Michel, Schmidt, Schimmelmann, Maric and Salokangas5 Basic symptoms have also been linked to other forms of mental illness, including affective disordersReference Michel, Ruhrmann, Schimmelmann, Klosterkötter and Schultze-Lutter15,Reference Schultze-Lutter, Michel, Ruhrmann and Schimmelmann16 and are associated with lower global functioning among individuals with a range psychiatric disorders.Reference Lo Cascio, Saba, Hauser, Lammers Vernal, Al-Jadiri and Borenstein17 However, the utility of basic symptoms as an indicator of risk for a broader range mental disorders remains to be examined.

Family high-risk approach

The best-known predictor of mood and psychotic disorders is a family history of illness.Reference Gottesman, Laursen, Bertelsen and Mortensen18 Risk of illness is proportional to the degree of biological relatedness to the affected individual.Reference Gottesman, Laursen, Bertelsen and Mortensen18 However, familial risk of mental illness is not disorder-specific. Individuals with a family history of schizophrenia are also at risk of mood disorders, and vice versa.Reference Rasic, Hajek, Alda and Uher19 This finding is supported by molecular data that show that a substantial proportion of genetic variants and gene expression abnormalities associated with mental illness are shared across psychiatric disorders.Reference Gandal, Haney, Parikshak, Leppa, Ramaswami and Hartl8,9,Reference Forstner, Hecker, Hofmann, Maaser, Reinbold and Muhleisen20,Reference Selzam, Coleman, Moffitt, Caspi and Plomin21 Taken together, these findings suggest that it may be useful to identify measurable experiences and behaviours that predict SMPD and are shared across disorders. By examining early manifestations of risk among offspring of parents with SMPD, we are able to distinguish possible causes or predictors of illness from the effects of SMPD and its treatment. Individuals who have a first-degree biological relative living with schizophrenia experience more basic symptoms than controls.Reference Meng, Graf Schimmelmann, Koch, Bailey, Parzer and Gunter22,Reference Klosterkötter, Gross, Huber, Wieneke, Steinmeyer and Schultze-Lutter23 However, basic symptoms have not yet been examined among youth at high familial risk for other forms of mental illness.

Aims

Here we examine the relationship between basic symptoms and family history of a spectrum of non-severe mood disorders (NSMD) and SMPD. We assessed basic symptoms in a sample of youth enriched for offspring of parents with major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, including both NSMD and SMPD. We aimed to test whether offspring basic symptoms are associated with parent mental illness, its severity, psychotic features or specific psychiatric diagnosis.

Method

Participants

The present study includes information from 909 assessments of 332 participants aged 8–26 years from 201 families, enrolled in the Families Overcoming Risks and Building Opportunities for Well-being (FORBOW) study.Reference Uher, Cumby, MacKenzie, Morash-Conway, Glover and Aylott24 Assessors masked to information on parents, assessed basic symptoms annually with the baseline assessment occurring at an average age of 11.84 years (range 8–24 years). Each participant completed a median of three assessments (range 1–6) at 12-month intervals. Repeated basic symptom measures from all assessments were included in analyses. We included offspring of parents with major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, psychosis spectrum disorders and offspring of control parents. Offspring of parents with SMPD were recruited through their parents' contact with mental health services in Nova Scotia, Canada. Offspring were included regardless of whether or not they had psychopathology. Age matched offspring of control parents were recruited through local school boards. To ensure that control offspring were approximately matched with offspring of affected parents on socioeconomic status, we selectively recruited control offspring from the same schools and neighbourhoods of the offspring of affected parents. We excluded offspring with a lifetime diagnosis of schizophrenia (n = 2 observations), schizoaffective disorder (n = 2 observations) or bipolar disorder (n = 8 observations).

We assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the Nova Scotia Health Authority (file number 100 266). We obtained written informed consent from participants who had the capacity to provide it. For participants who did not have the capacity to make an informed decision, a parent or guardian provided written informed consent and the participant provided assent.

Parent assessment

Diagnoses of mental disorders and psychotic symptoms according to the DSM-IV and DSM-5 were established using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS-IV)Reference Endicott25 or the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders (SCID-5).Reference First, Cautin and Lilienfeld26 Diagnoses were confirmed in consensus meetings with a psychiatrist masked to offspring psychopathology.

We defined SMPD as a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder or a psychosis spectrum disorder accompanied by two or more of the following five severity criteria: (a) recurrent, (b) chronic, (c) presence of psychotic symptoms, (d) life-threatening suicide attempt(s) or (d) required hospital admission.Reference Uher, Cumby, MacKenzie, Morash-Conway, Glover and Aylott24 We defined NSMD as a diagnosis of any Axis I mood disorder that did not meet two or more severity criteria. In situations where one biological parent had NSMD and one biological parent had SMPD, the offspring were placed in the SMPD group.

Offspring assessment

General psychopathology

Offspring were assessed for all Axis I disorders at 12-month intervals using the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia – Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL; in offspring younger than 18 years)Reference Kaufman, Birmaher, Brent, Rao, Flynn and Moreci27 or the SCID-5 (in offspring ≥18 years old).Reference First, Cautin and Lilienfeld26 A single assessor completed both the diagnostic interview and the basic symptoms interview. Offspring assessors were masked to parent psychopathology. Diagnoses were confirmed in consensus meetings with a psychiatrist masked to parent diagnoses.

Basic symptoms

We assessed basic symptoms using the Schizophrenia Proneness Instrument – Child and Youth Version (SPI-CY).Reference Fux, Walger, Schimmelmann and Schultze-Lutter14 The SPI-CY was designed to be administered to children and youth and it has been used among children aged 8 years and older with good interrater reliability.Reference Fux, Walger, Schimmelmann and Schultze-Lutter14,Reference Schimmelmann, Michel, Martz-Irngartinger, Linder and Schultze-Lutter28 The SPI-CY contains two psychosis-risk basic symptom profiles: Cognitive-Perceptive (COPER) and Cognitive Disturbances (COGDIS). COGDIS items have been shown to strongly predict psychotic illness and are part of the clinical high-risk criteria that have been recommended for the early detection of psychosis.Reference Schultze-Lutter, Michel, Schmidt, Schimmelmann, Maric and Salokangas5 Descriptions of the items in both high-risk profiles are provided in the Appendix. We calculated the SPI-CY risk score as the total number of COPER or COGDIS items scored 3 (several times in a month or weekly) to 6 (daily), divided by the total number of items with a valid frequency rating. We calculated a COGDIS score, which incorporates the nine items included in the COGDIS criteria, using the same process. For analyses, we standardised the SPI-CY risk score and COGDIS score by the means and standard deviations of the control offspring scores.

Antecedent basic symptoms

It may be desirable to use a dichotomous indicator of basic symptoms in applications that require yes or no decisions. Therefore, we defined antecedent basic symptoms as the presence of COPER and/or COGDIS criteria.Reference Uher, Cumby, MacKenzie, Morash-Conway, Glover and Aylott24 We report the rates of offspring who met our predefined antecedent basic symptoms threshold at their first assessment and at any assessment.

Statistical analysis

We tested the effect of parent mental illness on offspring basic symptoms in mixed-effects linear regression models using the lme4 package,Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker29 implemented in R Studio (R version 3.4.3).30 We accounted for the non-independence of observations from related individuals and from repeated measures within the same individual by including family and individual identifiers as random effects in the models. We included fixed effects of age, biological gender and time in the study as covariates. To test the effect of parent's primary illness severity (control, NSMD, SMPD) on offspring basic symptoms, we fitted a linear mixed regression model with standardised offspring SPI-CY risk score as the dependent variable and parent illness severity as the independent variable. We tested the effect of parent psychosis (control, non-psychotic illness, psychotic illness) on offspring basic symptoms by fitting a linear mixed regression model with standardised offspring SPI-CY risk score as the dependent variable and parent psychosis as the independent variable. We tested the effect of parent's primary diagnosis (control, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, psychosis spectrum disorder) on offspring basic symptoms by fitting a linear mixed regression model with standardised offspring SPI-CY risk score as the dependent variable and parent diagnosis as the independent variable (see supplementary Tables 9 and 10 and supplementary Fig. 2 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.40). We also tested the effects of parent illness severity, parent psychotic symptoms and parent diagnosis on offspring COGDIS scores separately, using the same methodology as described above. Effect sizes are summarised with standardised beta coefficients and their 95% confidence intervals.

Sensitivity analyses

We opted not to exclude offspring with major depressive disorder from the primary analyses because depression was common and excluding it would reduce the representativeness of the sample. However, to ensure that our results were not unduly influenced by offspring depressive disorders, we performed sensitivity analysis by excluding observations in which offspring had experienced a major depressive episode within the 12 months prior to the assessment. Additionally, the prevalence and clinical significance of basic symptoms has been shown to vary with age.Reference Schultze-Lutter, Ruhrmann, Michel, Kindler, Schimmelmann and Schmidt31 As we included participants across a broad range of ages, we stratified analyses by age and tested the effect of parent illness severity (control, NSMD, SMPD) on offspring basic symptoms among participants aged 11 years and under and 12 years and older separately (see supplementary materials).

Results

Participant characteristics and basic symptom scores

The sample included 93 offspring of control parents, 92 offspring of a parent with NSMD and 147 offspring of a parent with SMPD. The characteristics of the participants and the rates of antecedent basic symptoms across parent groups are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of the participantsa

BS, basic symptoms.

a. Differences between groups were tested using univariate ANOVA for continuous variables or χ2 tests for categorical variables.

b. Denotes statistically significant group differences between the three groups.

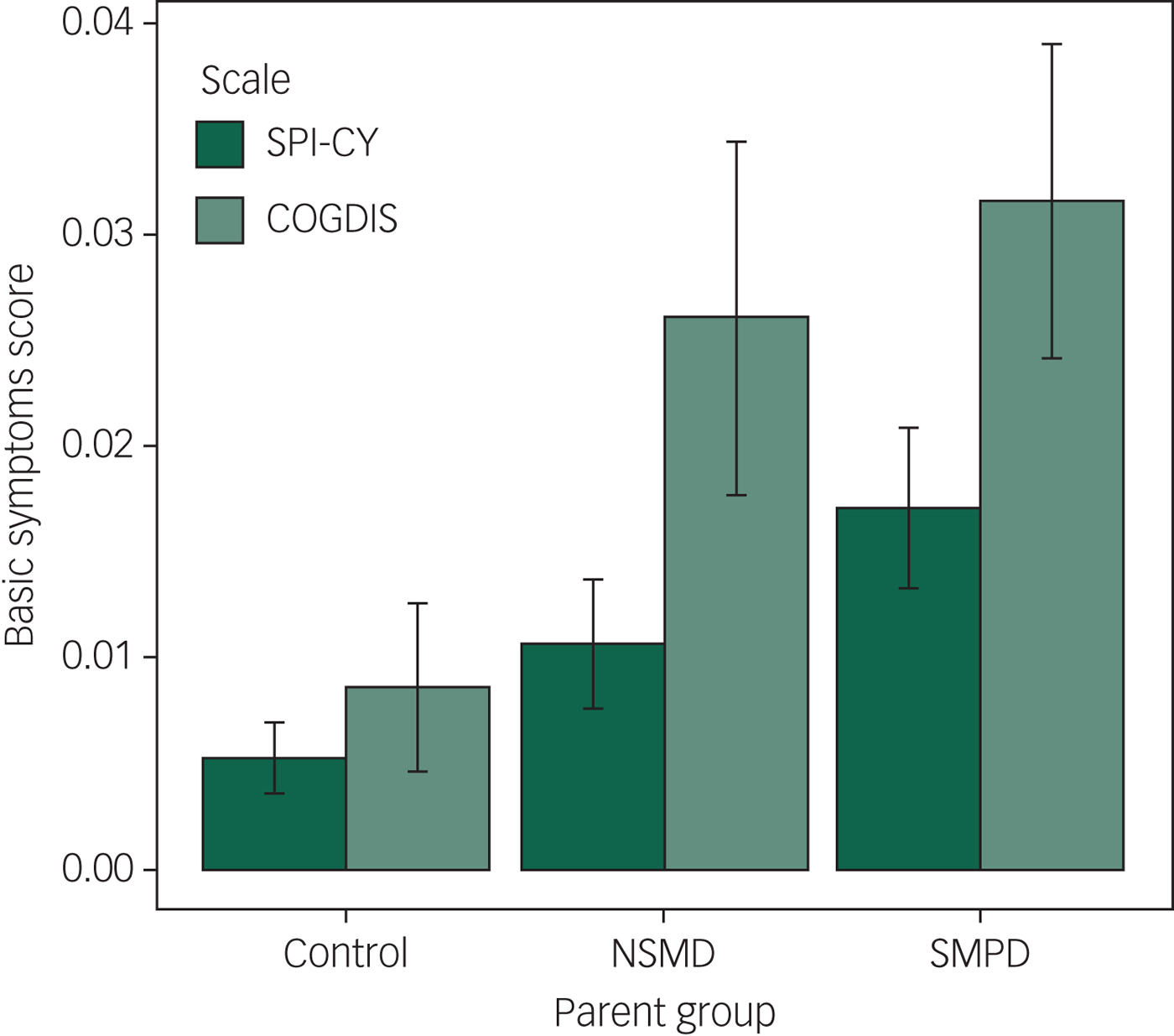

Differences in SPI-CY risk scores by parent illness severity

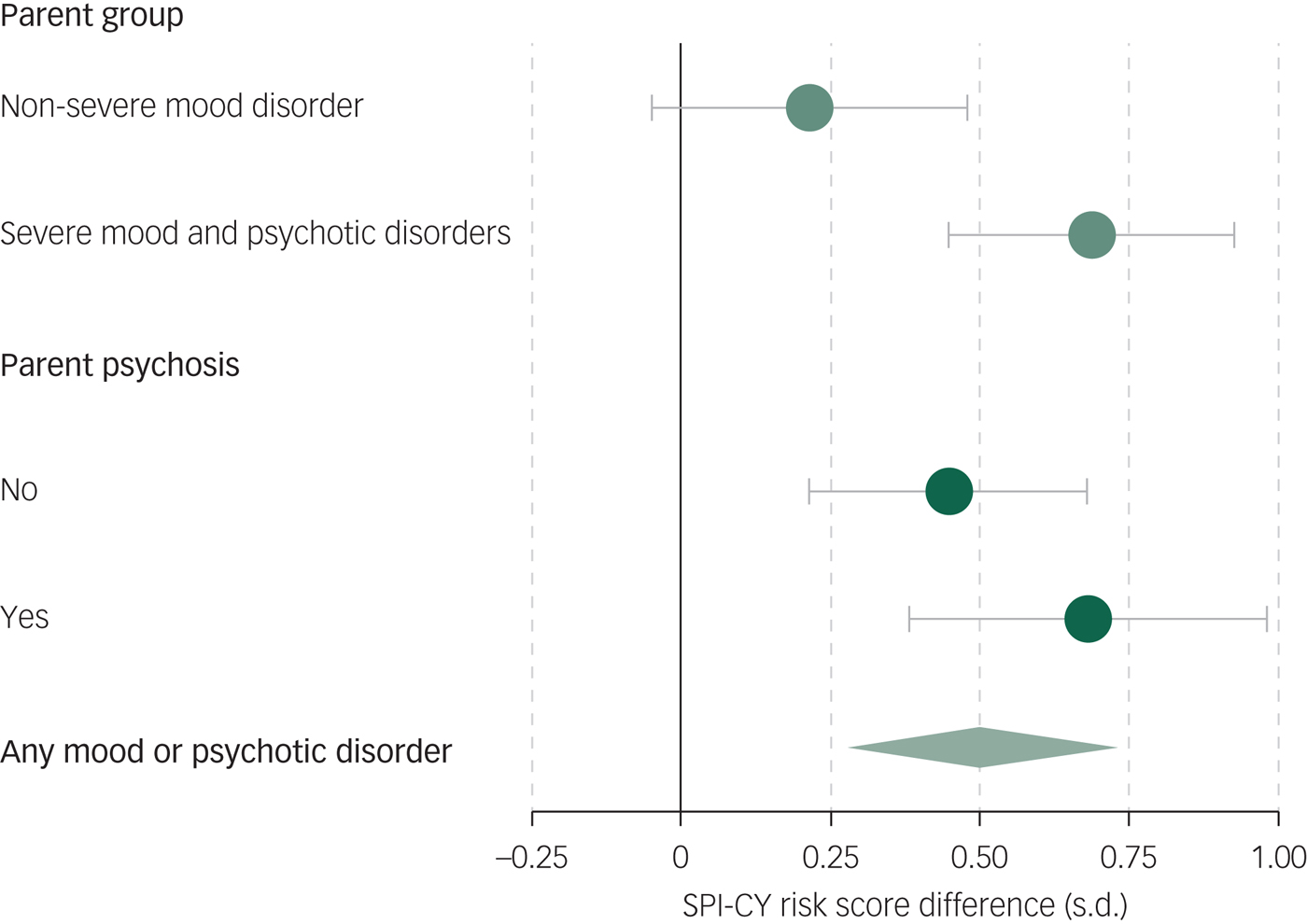

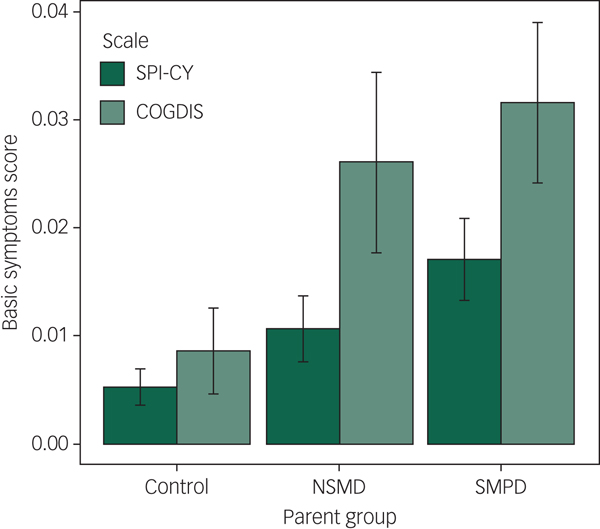

Across the 909 assessments of 332 children and youth with valid SPI-CY risk scores, basic symptoms were significantly elevated among the offspring of parents with SMPD compared with controls (B = 0.69, 95% CI 0.22–1.16, P = 0.004; see Figures 1 and 2). Basic symptom scores were numerically elevated among offspring of parents with NSMD, but this difference was not statistically significant (B = 0.22, 95% CI −0.30 to 0.73, P = 0.415). When we excluded observations at which offspring experienced a major depressive episode within 12 months prior to the assessment, basic symptoms remained significantly elevated among the offspring of parents with SMPD (B = 0.49, 95% CI 0.10–0.87, P = 0.014). Full regression results are shown in supplementary Tables 1 and 2. In age-stratified analyses, these findings remained consistent in both the younger (8–11 year olds) and older (12 years and older) subsets (see supplementary Tables 11 and 13 and supplementary Figs. 3 and 4).

Fig. 1 Mean Schizophrenia Proneness Instrument – Child and Youth Version (SPI-CY) risk score and Cognitive Disturbances (COGDIS) score, stratified by parent illness severity group.

Fig. 2 Effect of parent illness on offspring basic symptoms.

Differences in COGDIS score by parent illness severity

Across the 905 assessments of 331 children and youth with valid COGDIS scores, basic symptoms were significantly elevated among the offspring of parents with SMPD compared with controls (B = 0.53, 95% CI 0.13–0.93, P = 0.009; see Figs. 1 and 2). When we excluded observations at which offspring experienced a major depressive episode within 12 months prior to the assessment, basic symptoms remained significantly elevated among the offspring of parents with SMPD (B = 0.39, 95% CI 0.04–0.73, P = 0.028). Full regression results are shown in supplementary Tables 3 and 4. In age-stratified analyses, COGDIS scores were numerically increased among offspring of parents with SMPD, however these differences were only statistically significant in the younger (8–11 year olds) subset (see supplementary Tables 12 and 14 and supplementary Figs. 3 and 4).

Differences in basic symptom scores by parent psychosis

Across the 909 assessments of 332 children and youth with valid SPI-CY risk scores, basic symptoms were significantly elevated among offspring of a parent with psychotic mental illness compared with controls (B = 0.68, 95% CI 0.09–1.27, P = 0.023; see supplementary Fig. 1). Offspring of a parent with non-psychotic mental illness had numerically higher SPI-CY risk scores than controls, but this difference was not statistically significant (B = 0.45, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.90, P = 0.055, see supplementary Fig. 1). When we excluded observations in which offspring experienced a major depressive episode within 12 months prior to the assessment, both the offspring of parents with psychotic mental illness (B = 0.44, 95% CI −0.05 to 0.92, P = 0.078) and with non-psychotic mental illness (B = 0.35, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.72, P = 0.067) had numerically higher SPI-CY risk scores than controls, but the difference was not statistically significant. Similarly, COGDIS scores were significantly elevated among the offspring of parents with psychotic mental illness (B = 0.55, 95% CI 0.05 to 1.04, P = 0.030) and with non-psychotic mental illness (B = 0.41, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.80, P = 0.037). Full regression results are shown in supplementary Tables 5–8.

Antecedent basic symptoms

We defined antecedent basic symptoms as the presence of COPER and/or COGDIS high-risk criteria. The rate of youth meeting these high-risk criteria increased with increasing parent severity: 12.9% control offspring, 17.4% of offspring of parents with NSMD and 23.8% of offspring of parents with SMPD had antecedent basic symptoms at baseline (Table 1).

Discussion

Main findings

We sought to test whether basic symptoms during childhood and adolescence are elevated among offspring of parents with a spectrum of NSMD and SMPD. We found that basic symptoms were most elevated among offspring of parents with SMPD, intermediate in offspring of parents with NSMD, and lowest in offspring of control parents.

Comparison with findings from other studies

Our study was motivated by a need to identify early transdiagnostic indicators of risk for SMPD among youth. Previous studies have established that basic symptoms predict psychosis, and can be present years before its onset.Reference Schultze-Lutter, Michel, Schmidt, Schimmelmann, Maric and Salokangas5,Reference Klosterkötter and Hellmich32 However, basic symptoms have not been previously examined among offspring of parents with a broad range of major mood and psychotic disorders. Consistent with prior studies which show offspring of parents with mental illness are at risk of developing psychopathology themselves,Reference Rasic, Hajek, Alda and Uher19 we found that basic symptoms are elevated among the offspring of parents with SMPD compared with controls. We also confirmed that basic symptom scores are elevated among first-degree relatives of individuals with psychosis.Reference Klosterkötter, Gross, Huber, Wieneke, Steinmeyer and Schultze-Lutter23 Our results are consistent with prior findings showing that offspring of parents with SMPD are at increased risk for multiple forms of psychopathology, in addition to the disorder present in the parent.Reference Rasic, Hajek, Alda and Uher19 Additionally, it has been suggested that psychosis may represent a transdiagnostic indicator of illness severity.Reference van Os and Reininghaus33,Reference van Os and Guloksuz34 This is supported by studies showing that the presence of psychotic symptoms in non-psychotic disorders has been associated with more severe illness and worse treatment outcomes.Reference Perlis, Uher, Ostacher, Goldberg, Trivedi and Rush35–Reference Wigman, van Os, Abidi, Huibers, Roelofs and Arntz38 Our results suggest that basic symptoms represent a transdiagnostic marker of risk for SMPD that is not specific to psychotic illness.

Strengths and limitations

The present study benefits from the inclusion of offspring of parents with mental illness, resulting in a concentration of familial risk of psychopathology. As a result, our sample has a higher rate of basic symptoms than in the general population. We also benefit from a longitudinal design, with repeated assessments allowing the capture of basic symptoms over the period of several years. However, our results should be interpreted in the context of our study limitations. The main limitation is the smaller number of offspring of parents with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder. The majority of parents in our sample who experience psychosis have bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder with psychotic features. The smaller enrolment of offspring of parents with schizophrenia may be in part be because individuals with schizophrenia tend to have fewer children.Reference Power, Kyaga, Uher, MacCabe, Langstrom and Landen39 However, enrolment in our cohort is ongoing and will include more offspring of parents with schizophrenia spectrum disorders in the future. Additionally, since basic symptoms are more prevalent and may be more clinically relevant among older adolescents,Reference Schimmelmann, Michel, Martz-Irngartinger, Linder and Schultze-Lutter28,Reference Schultze-Lutter, Ruhrmann, Michel, Kindler, Schimmelmann and Schmidt31 our study was limited by the inclusion of younger adolescents and children. However, in our age-stratified sensitivity analyses, we found that basic symptom scores were independently associated with parent mental illness among 8- to 11-year-old and 12- to 27-year-old offspring.

Implications

The results of our study have potential implications for future research. The finding that basic symptoms are elevated among young offspring of parents with SMPD can help target interventions to youth at high risk of mood and psychotic disorders, long before the onset of illness. Interventions aimed at preventing psychosis among individuals experiencing prodromal symptoms have been criticised, in part because ‘good’ outcomes may be synonymous with onsets of other, non-psychotic illnesses among intervention recipients.Reference van Os and Guloksuz34 It has been shown that earlier interventions produce better outcomes.Reference Heckman40,Reference Bayer, Rapee, Hiscock, Ukoumunne, Mihalopoulos and Wake41 Our results suggest that basic symptoms may represent a useful transdiagnostic risk indicator. Basic symptoms could be used, in combination with other factors, to identify high-risk youth who may benefit from targeted interventions before the onset of major mental illnesses. Our results warrant further investigation in other familial high-risk cohorts. Additionally, the basic symptom assessment toolReference Fux, Walger, Schimmelmann and Schultze-Lutter14 could be adopted by cohorts currently using interview measures of psychopathology.

In conclusion, we found that basic symptoms are elevated among offspring of parents with SMPD, in addition to offspring of parents with psychosis. Our results suggest that basic symptoms during childhood are a marker of familial risk for psychopathology that is related to severity and is not specific to psychotic illness. Future studies could explore the value of basic symptoms as a transdiagnostic predictor of mental illness.

Funding

The work leading to this publication has been supported by funding from the Canada Research Chairs Program (award number 231397), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grant reference numbers 124976, 142738 and 148394), the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation (NARSAD) Independent Investigator Grant 24684, Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation (grants 275319, 1716 and 353892) and the Dalhousie Medical Research Foundation. A.Z. has been supported by the Lindsay Family Graduate Studentship. V.D. was supported by the CIHR Doctoral Award (157975).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the families who have participated in FORBOW. The authors would also like to acknowledge the contributions of the FORBOW research team (see http://www.forbow.org).

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.40.

Appendix

Appendix Items included in the basic symptoms high-risk profiles.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.