Intellectual disabilities are a group of aetiologically diverse conditions originating during the developmental period, characterised by significantly below-average intellectual functioning and adaptive behaviour that are approximately two or more standard deviations below the mean, based on appropriately normed, individually administered standardised tests.1

Epilepsy in adults with intellectual disabilies

The prevalence of epilepsy is much higher in adults with intellectual disabilities (>25%) than in the general population (1%).Reference Deb2 Compared with the general population, epilepsy among adults with intellectual disabilities is not only more prevalent, but often manifests as multiple seizure types, starts at an early age, is of longer duration and is more treatment-resistant (around 30% in the general population compared with >70% in people with intellectual disabilities).Reference Shankar, Watkins, Alexander, Devapriam, Dolman and Hari3 Diagnosing epilepsy and seizure types can be difficult in this population. For example, stereotypy, cardiac syncope and non-epileptic attack disorders may all mimic epileptic seizures. On the other hand, absence and partial seizures may be particularly challenging to detect in this population.Reference Deb, Jacobson, Mulick and Rojahn4 Thus, both a false positive and a false negative diagnosis are possible.Reference Deb, Jacobson, Mulick and Rojahn4 Also, people with intellectual disabilities are more prone to die from sudden unexpected death in epilepsy.Reference Shankar, Eyeoyibo, Scheepers, Dolman, Watkins and Attavar5

Epilepsy and psychiatric disorders in the general population

Studies in the general population found an increased rate of psychiatric disorders in adults with epilepsy. For example, the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders is reported to be 20–30%, whereas psychoses are estimated to be 2–7% in the general population with epilepsy.Reference Lin, Mula and Hermann6 These figures are higher than the point prevalence of 17% of mood and anxiety disorders and 1–2% of psychoses observed among the general population who do not have a diagnosis of epilepsy.Reference McManus, Bebbington, Jenkins and Brugha7 The affective disorders tend to be present at all stages of epilepsy, whereas psychosis is particularly prevalent in the post-ictal phase.

Psychiatric disorders in intellectual disabilities

If problem (challenging) behaviour and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are included, the overall rate of mental ill health seems higher in adults with intellectual disabilities (40.9%)Reference Cooper, Smiley, Morrison, Williamson and Allan8 than in the general population (16%).Reference Meltzer, Gill, Petticrew and Hinds9 However, excluding the diagnosis of ASD and problem behaviour, the rate of overall functional psychiatric disorders (14.5%)Reference Cooper, Smiley, Morrison, Williamson and Allan8,Reference Deb, Thomas and Bright10 is similar to that in the general population (16%).Reference Meltzer, Gill, Petticrew and Hinds9 The point prevalence of psychosis including schizophrenia is significantly higher in adults with intellectual disabilities (3.4–4.4%)Reference Deb, Thomas and Bright10–Reference White, Chant, Edwards, Townsend and Waghorn12 compared with adults without intellectual disabilities (1%).Reference Meltzer, Gill, Petticrew and Hinds9,Reference Sartorius, Ustün, Lecrubier and Wittchen13 Although depressive symptoms are reported in 16.5% of adults with intellectual disabilities, the rate of major depressive disorder seems similar in both adults with intellectual disabilities (2.2–8%)Reference Cooper, Smiley, Morrison, Williamson and Allan8,Reference Deb, Thomas and Bright10,Reference White, Chant, Edwards, Townsend and Waghorn12 and adults without intellectual disabilities (2.1%).Reference Meltzer, Gill, Petticrew and Hinds9 The rate of anxiety disorder seems higher in adults with intellectual disabilities (14%)Reference White, Chant, Edwards, Townsend and Waghorn12 than in the general population (10%).Reference Sartorius, Ustün, Lecrubier and Wittchen13 However, diagnosis of psychiatric disorders could be difficult in many adults with intellectual disabilities, particularly those who have a severe and profound intellectual disability and cannot communicate their thoughts and feelings to others.Reference Deb, Matthews, Holt and Bouras14 Therefore, both a false positive and a false negative diagnosis are possible.

The need for this systematic review

The question of whether there is an association between epilepsy and psychiatric disorders in adults with intellectual disabilities remains unanswered. We found only one systematic review of neuropsychiatric conditions in people with intellectual disabilitiesReference van Ool, Snoeijen-Schouwenaars, Schelhaas, Tan, Aldenkamp and Hendriksen15 that included 15 studies, but only two of these are specifically on psychiatric disorders per se, and the rest are mostly on problem behaviour. Also, the previous review included participants of all ages and did not present data separately on adults, which is the focus of the current review. We have already published a systematic review with meta-analysis specifically on the relationship between epilepsy and problem behaviour in adults with intellectual disabilities.Reference Deb, Akrout Brizard and Limbu16 As there is currently no published systematic review and meta-analysis available specifically on the association between psychiatric disorders and epilepsy in adults with intellectual disabilities, we have carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis on studies that explored this relationship. We have concentrated on studies of adults with intellectual disabilities only, as the issues concerning children with intellectual disabilities are different from those of adults.

Method

Search strategy

Protocol and search strategy were based on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) guidelines17 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) checklist.Reference Moher, Shamseer, Clarke, Ghersi, Liberati and Petticrew18 The study was registered with PROSPERO, under registration number CRD42020178083.

Four electronic databases were searched for relevant studies: EMBASE, PsycINFO, PubMed and DARE. The electronic search focused on articles published in English and French, between 1 January 1985 and 31 May 2020. Hand-searching for relevant articles was carried out in the past 10 years of issues, from January 2000 to June 2020, in the following journals: Seizure, Epilepsia, Epilepsy & Behavior, Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities and Research in Developmental Disabilities. Only quantitative studies were searched.

Search terms

Each database was searched using terms for intellectual disability, epilepsy and psychiatric disorders.

Terms for intellectual disabilities were: ‘Intellectual disability’ OR ‘Learning disability’ OR ‘Learning disorder’ OR ‘Learning difficulties’ OR ‘Mental disabilities’ OR ‘Neurodevelopmental disorders’ OR ‘NDD’ OR ‘ID’ OR ‘LD’ OR ‘Mental retardation’ OR ‘Mental handicap’ OR ‘Mental deficiency’.

The following search terms were used to cover psychiatric disorders: ‘Psychiatric illness’ OR ‘Psychiatric disorders’ OR ‘Schizophrenia’ OR ‘Psychosis’ OR ‘Depression’ OR ‘Major depressive disorder’ OR ‘Bipolar disorder’ OR ‘Mania’ OR ‘Hypomania’ OR ‘Anxiety disorders’ OR ‘Anxiety’ OR ‘Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder’ OR ‘OCD’ OR ‘Phobia’ OR ‘Phobic disorders’ OR ‘Personality disorder’ OR ‘Dementia’.

Terms for epilepsy were: ‘Epilepsy’ OR ‘Epilepsy syndrome’ OR ‘Seizures’ OR ‘Seizure disorders’ OR ‘Epileptic seizures’ OR ‘AED’ OR ‘Anti-epileptic drugs’.

Criteria for selecting studies for this review

A list of eligibility criteria, based on PROSPERO guidelines17 and Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions,Reference Lefebvre, Glanville, Briscoe, Littlewood, Marshall, Metzendorf, Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch19 was adapted. The eligibility criteria for the review were (a) an epilepsy and intellectual disabilities group compared with a non-epilepsy group of adults with intellectual disabilities alone (if the study did not have a non-epilepsy control group, the study had to provide information on psychiatric disorders, epilepsy-related factors and anti-epileptic drug regimen); (b) all participants had intellectual disabilities; (c) all participants were defined as adults by the authors and (d) a minimum sample size of ten participants.

Types of studies

This review included studies with different designs. Both randomised and non-randomised studies, and both controlled and non-controlled observational or cross-sectional studies, were included. Controlled studies with both matched and non-matched control groups were included.

We included studies that compared the overall rate of psychiatric disorders, as well as different types of psychiatric disorders in adults with intellectual disabilities and epilepsy, with a group of adults with intellectual disabilities without epilepsy within the same cohort.

We also included studies that included participants with intellectual disabilities and epilepsy, but no participants with intellectual disabilities without epilepsy. These studies allowed assessment of the association of psychiatric disorders with epilepsy-related variables.

Studies were included regardless of the method used to assess the rate of any psychiatric disorders and specific psychiatric disorders, such as affective disorders, psychosis, anxiety disorders, personality disorders and dementia. In that, studies reporting data with standardised assessment tools, case notes, symptom checklists and semi-structured interviews administered by clinicians or trained professionals were included.

Types of participants

All participants were adults aged ≥16 years, had intellectual disabilities (all levels of severity) and had various types of psychiatric disorders. This review focuses on data on psychiatric disorders and does not present data on problem behaviour, as a separate systematic review has been published recently on the association between epilepsy and challenging (problem) behaviour in adults with intellectual disabilities.Reference Deb, Akrout Brizard and Limbu16

Ethical approval was not required for this study because no individual patient-related data were collected or analysed.

Secondary outcome

Comparison between epilepsy and non-epilepsy groups was carried out for different types of psychiatric disorders (psychotic disorders, depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, personality disorders and dementia). To identify the role of different epilepsy-related factors in the development of psychiatric disorders, data on subgroup comparisons according to types of seizures, frequency of seizures and drug regimen (e.g. polypharmacy versus mono-pharmacy) were collected.

Selection process

After completion of each database search, references were recorded on Zotero reference management software version 5.0.77 for Windows (Corporation for Digital Scholarship, George Mason University, US; see https://www.zotero.org/download/).20 Titles were searched for key terms. Non-human studies, studies involving children and people without intellectual disabilities were removed. Duplicates were identified by Zotero, and removed manually by the first author (B.A.B.). Independent screening of the remaining abstracts was carried out by B.A.B. and B.L., using pre-piloted eligibility criteria. The review authors were blind to each other's scores. Discrepancies identified were reviewed and discussed until resolution of differences by consensus. Full texts were gathered for the studies that met the inclusion criteria or the ones marked as uncertain. The full texts were then reviewed and assessed by both reviewers (B.A.B. and B.L.), using the same eligibility checklist that was used for screening abstracts.

The selection process is reported in a PRISMA flow diagram (see Fig. 1). It was not necessary for a third review author (S.D.) to arbitrate.

Fig. 1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis flow chart of the study selection process.

Data extraction

Data from studies meeting eligibility criteria were extracted by both reviewers (B.A.B. and B.L.), using a standardised data extraction proforma adapted from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (see Supplementary Appendix 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.55).Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li and Welch21 The third review author (S.D.) checked the collected data for accuracy. Data extraction started on 8 July 2020. We have presented data separately on the more recently published studies since 2010 because definitions of epilepsy, intellectual disabilities and psychiatric disorders have changed in the past decade.

Meta-analysis

We used RevMan version 5.3 for Windows 10 (The Cochrane collaboration, London, UK; see https://training.cochrane.org/online-learning/core-software-cochrane-reviews/revman/revman-5-download) meta-analysis software for the random-effects model. The random-effects model was used because of differing study designs.

As most studies presented prevalence rates among different groups but a few others presented the mean and s.d., we only included studies presenting prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders in each group (epilepsy versus non-epilepsy group) for meta-analysis. A forest plot was constructed for comparison, for which we reported the pooled odds ratio, 95% confidence interval and a P-value. The statistical significance level was set at P < 0.05. Heterogeneity was tested with χ 2 and I 2 values. Heterogeneity was considered minimal when under 40% and substantial when over 50%, according to guidelines from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li and Welch21 Sensitivity analysis was carried out when heterogeneity was considered substantial.

Risk of bias assessment

The Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN 50) checklistReference Harbour and Forsyth22 was used to assess the quality of the 29 included studies. Additionally, the risk of bias for 25 controlled studies was assessed by the Cochrane risk of bias tool.Reference Sterne, Savović, Page, Elbers, Blencowe and Boutron23

Confidence in the cumulative estimate

We assessed publication bias with a funnel plot and Egger's test, and assessed the included studies for consistency and precision. We excluded any studies deemed of low quality. We assessed the quality of the systematic review by using A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews 2nd edition (AMSTAR-2) criteria (see Supplementary Appendix 2).Reference Shea, Reeves, Wells, Thuku, Hamel and Moran24

Results

Search findings

A total of 2594 articles were screened based on titles. After screening with the eligibility criteria, 2539 articles were excluded. The remaining 55 abstracts were in English, and no studies in French were selected for abstract screening. We screened 55 abstracts with the eligibility criteria, and excluded 11 citations.

With an additional six citations detected through hand-searching and cross-referencing, a total of 50 full texts were screened with the eligibility criteria. Of these, 29 articles met the eligibility criteria and were ultimately included in the systematic review (see Fig. 1). A list of excluded articles with the reason for exclusion is presented in Supplementary Appendix 3.

Included studies

Twenty-nine papers were included in our systematic review. Three articles published data on the same cohort but different outcome measures. Six studies included participants >16 years of age, three studies included participants >17 years of age and three stated that the participants were adults. We have included all these studies, as authors defined the study population as adults, and age cut-off for defining adulthood varies from country to country. for legal and administrative purposes. Of the 29 studies, 11 were controlled studies of comparison of the overall rate of psychiatric disorders (two of which were matched), and 14 were controlled studies that presented data on specific psychiatric disorders between epilepsy and non-epilepsy groups. Four studies included only participants with intellectual disabilities and epilepsy, and did not have a control group. Table 1 presents data from studies that compared data on the overall rate of psychiatric disorders in adults with intellectual disabilities and epilepsy and adults with intellectual disabilities who did not have epilepsy. In two studies,Reference Deb and Hunter25,Reference Matthews, Weston, Baxter, Felce and Kerr26 the groups were matched, and the number of participants remained the same in the epilepsy and non-epilepsy groups. In the remaining nine studies, the two groups of adults with intellectual disabilities with and without epilepsy were not matched. Reference Deb, Thomas and Bright10,Reference Arshad, Winterhalder, Underwood, Kelesidi, Chaplin and Kravariti27–Reference Mantry, Cooper, Smiley, Morrison, Allan and Williamson34 In the unmatched studies, the prevalence of psychiatric disorders was collected in a larger sample of adults with intellectual disabilities, only a proportion of whom (around 27%) had epilepsy. The rates of psychiatric disorders were compared between adults with intellectual disabilities with and without epilepsy within the same sample, but the two groups were not matched.

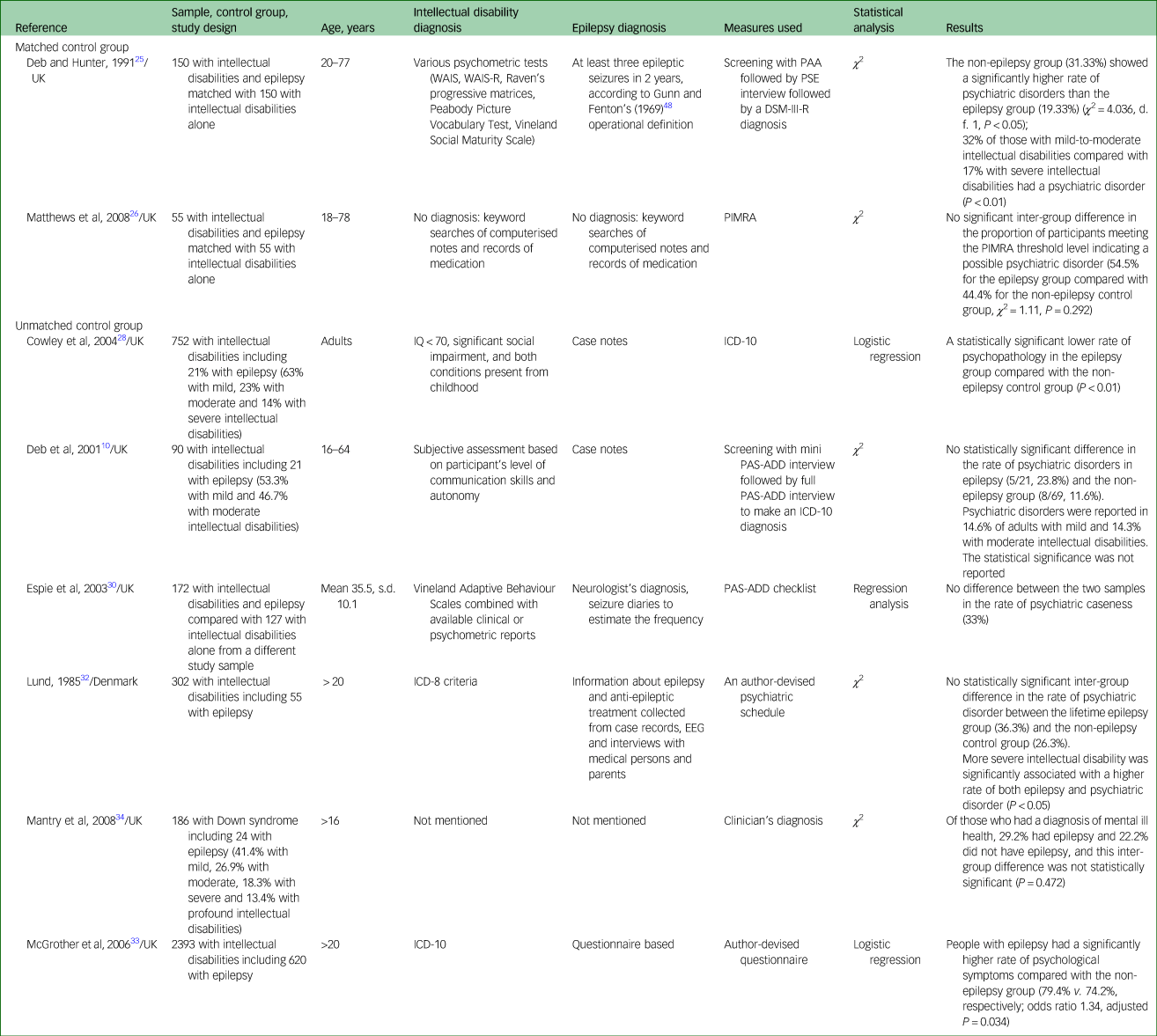

Table 1 The rates of psychiatric disorders in adults with intellectual disabilities and with and without epilepsy

WAIS, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, WAIS-R, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Revised; PAA, Profile of Abilities and Adjustment Schedule; PSE, Present State Examination; PIMRA, Psychopathology Instrument for Mentally Retarded Adults; PAS-ADD, Psychiatric Assessment Schedule for Adults with Developmental Disabilities; EEG, electroencephalogram.

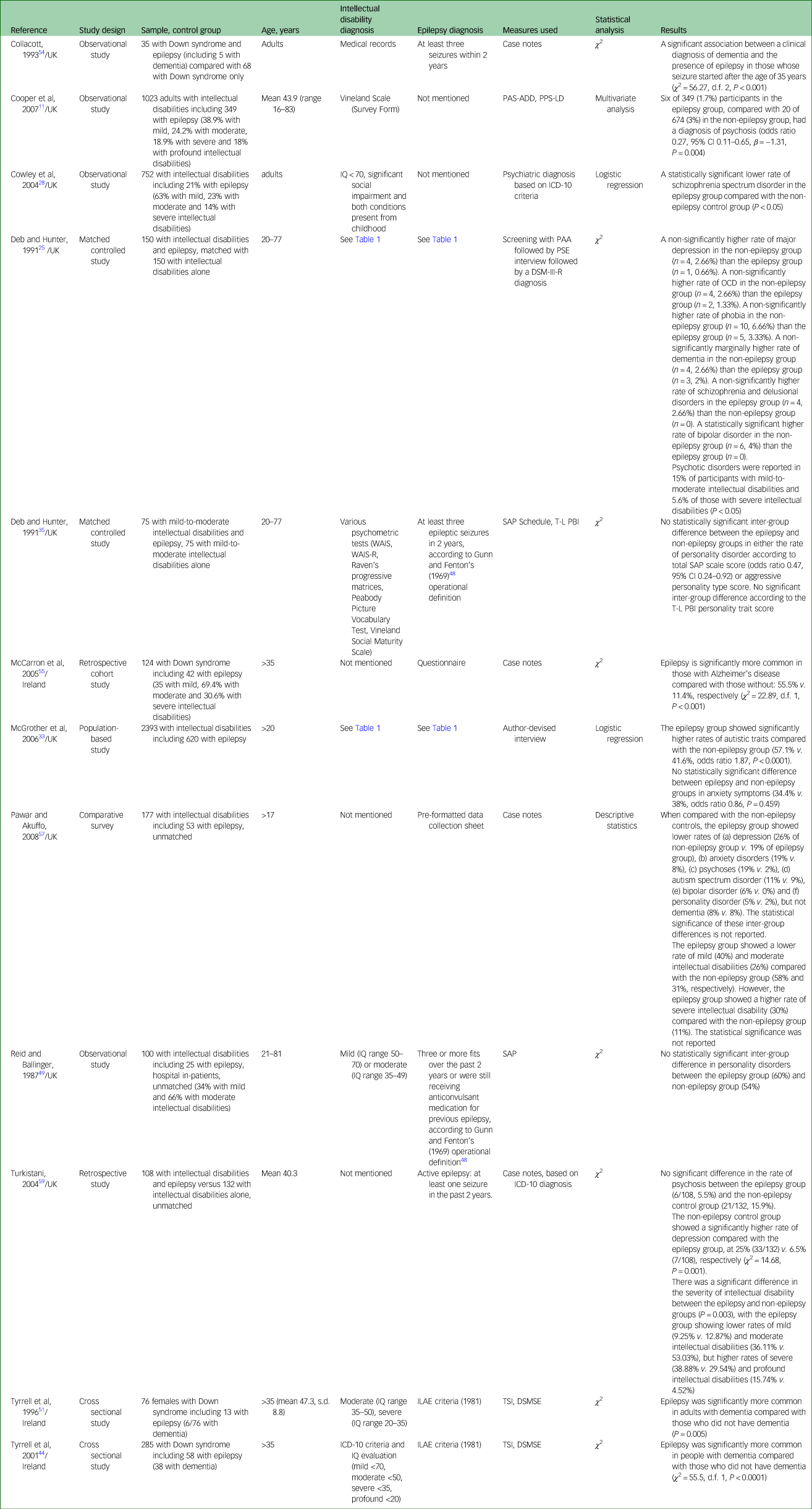

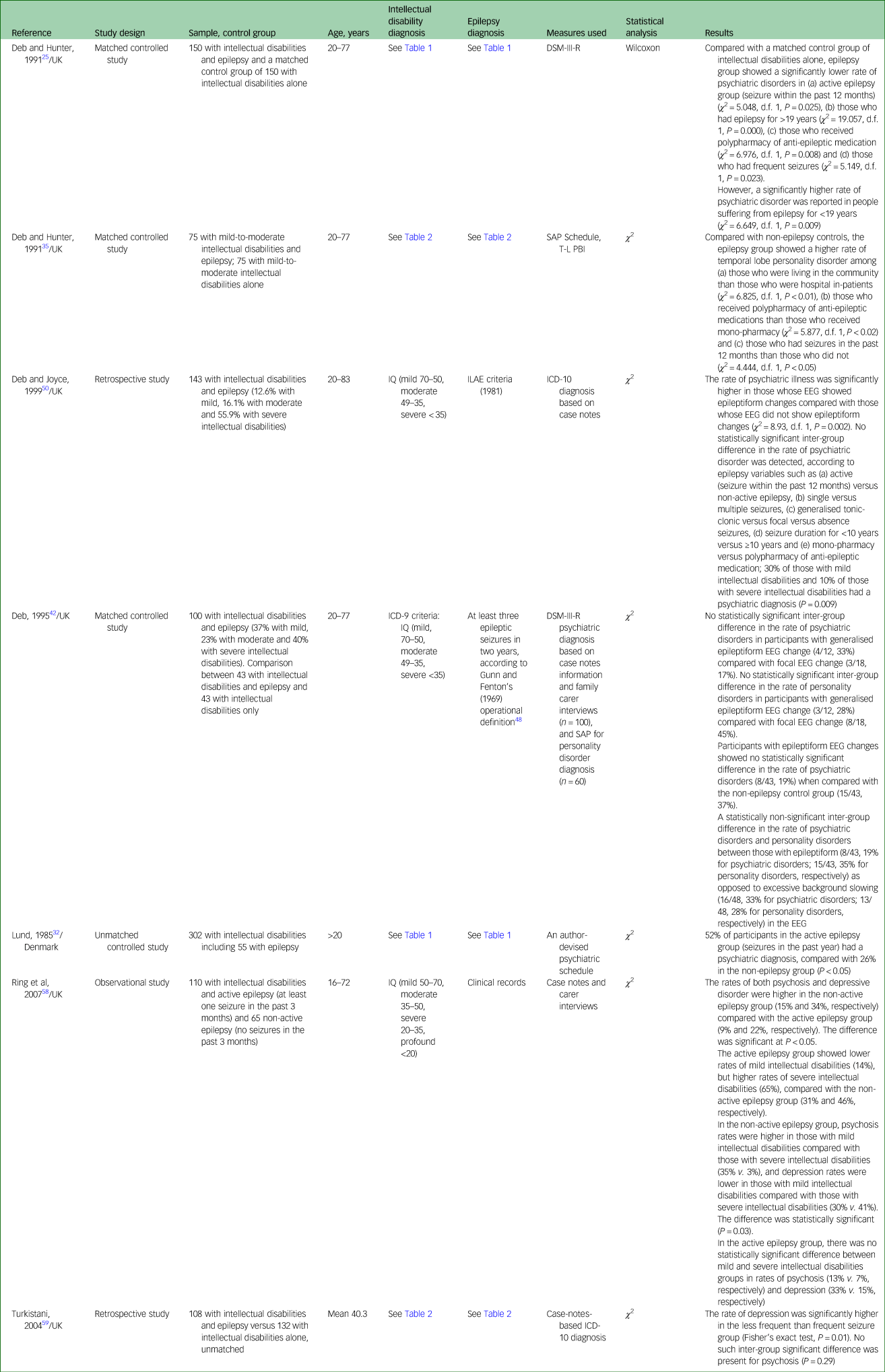

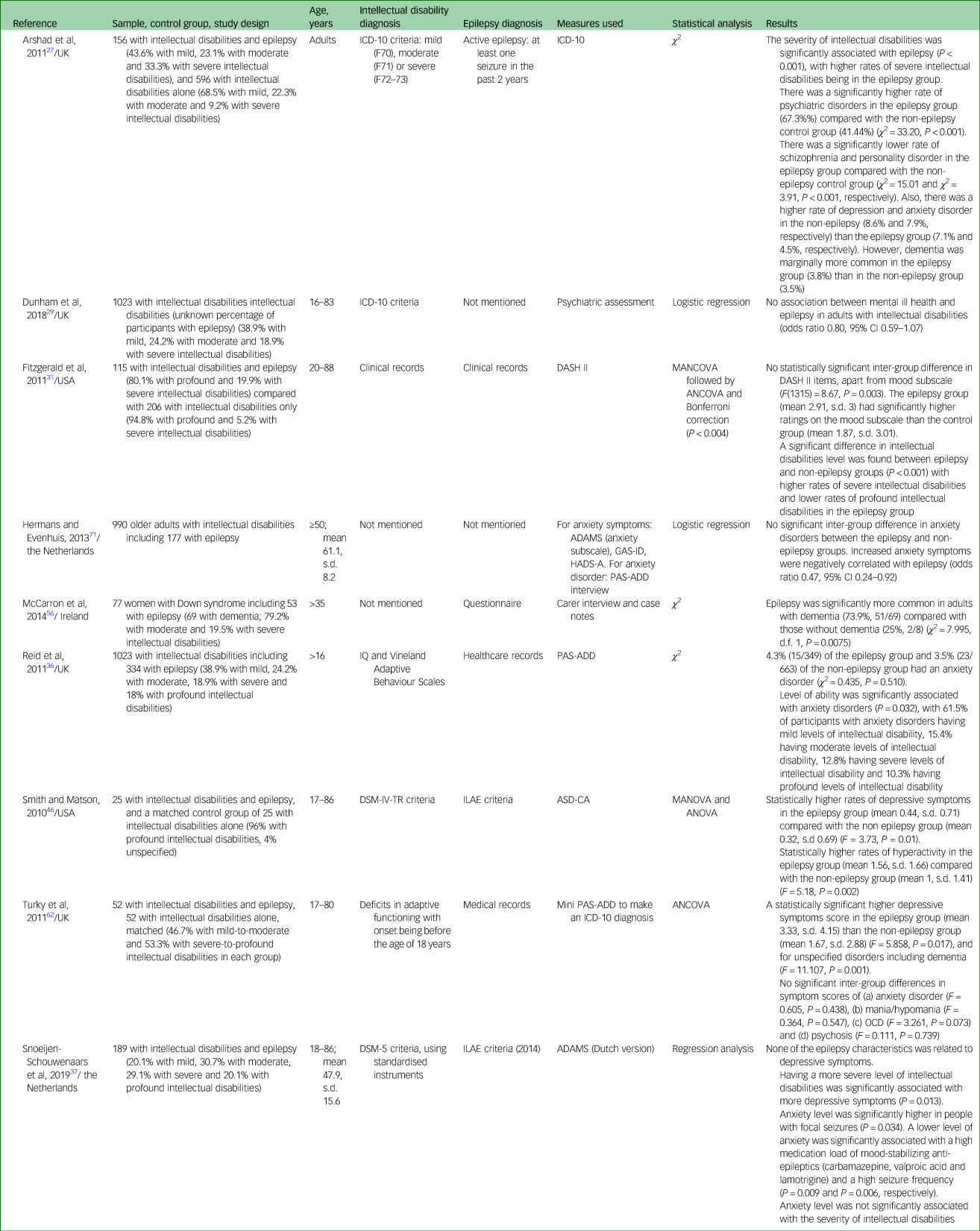

Table 2 presents data on the rates of different types of psychiatric disorders with comparisons between epilepsy and non-epilepsy groups of adults with intellectual disabilities. Table 3 includes data on epilepsy-related factors associated with psychiatric disorders in adults with intellectual disabilities and epilepsy. Table 4 presents data separately on the studies published in the past decade (2010 onward).

Table 2 Types of psychiatric disorders in adults with intellectual disabilities and epilepsy

PAS-ADD, Psychiatric Assessment Schedule for Adults with Developmental Disabilities; PPS-LD, Psychopathology Schedule for Adults with Learning Disabilities; PAA, Profile of Abilities and Adjustment Schedule; PSE, Present State Examination; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; WAIS, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, WAIS-R, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Revised; SAP, Standardized Assessment of Personality; T-L PBI, Temporal Lobe Personality Behaviour Inventory; ILAE, International League Against Epilepsy; TSI, Test for Severe Impairment; DSMSE, Down Syndrome Mental Status Examination.

Table 3 Psychiatric disorders according to different epilepsy variables

SAP, Standardized Assessment of Personality; T-L PBI, Temporal-Lobe Personality Behaviour Inventory; ILAE, International League Against Epilepsy; EEG, electroencephalogram.

Table 4 Overall and specific psychiatric disorders in publications from 2010 onward

DASH-II, Diagnostic Assessment for the Severely Handicapped-II; MANCOVA, multivariate analysis of covariance; ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; ADAMS, Anxiety, Depression, And Mood Scale; GAS-ID, Glasgow Anxiety Scale for People with an Intellectual Disability; HADS-A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Anxiety Subscale; PAS-ADD, Psychiatric Assessment Schedule for Adults with Developmental Disabilities; ILAE, International League Against Epilepsy; ASD-CA, Autism Spectrum Disorders-Comorbidity for Adults version; MANOVA, multivariate analysis of variance; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder.

Of the included studies, 20 were in the UK, four were in Ireland, two were in the USA, two were in the Netherlands and one was in Denmark.

The studies present data from a total sample of 9594 adults with intellectual disabilities, which included 3180 with epilepsy and 6414 without epilepsy.

Diagnosis

Intellectual disabilities

Included studies used different methods to diagnose intellectual disabilities and evaluate severity. Six studiesReference Cooper, Smiley, Morrison, Allan, Williamson and Finlayson11,Reference Deb and Hunter25,Reference Espie, Watkins, Curtice, Espie, Duncan and Ryan30,Reference Deb and Hunter35–Reference Snoeijen-Schouwenaars, van Ool, Tan, Aldenkamp, Schelhaas and Hendriksen37 used standardised evaluation of intellectual disabilities with various psychometric tests, such as Wechsler Adult Intelligence ScaleReference Wechsler38 and Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales.Reference Sparrow, Balla and Cicchetti39,Reference Sparrow, Balla and Cicchetti40 Six studies referred to ICD criteria for intellectual disabilities diagnosis, with one studyReference Lund32 referring to the eighth edition,41 one studyReference Deb42 referring to the ninth edition43 and four studiesReference Arshad, Winterhalder, Underwood, Kelesidi, Chaplin and Kravariti27,Reference Dunham, Kinnear, Allan, Smiley and Cooper29,Reference McGrother, Bhaumik, Thorp, Hauck, Branford and Watson33,Reference Tyrrell, Cosgrave, McCarron, McPherson, Calvert and Kelly44 referring to the tenth edition.45 One studyReference Smith and Matson46 used the DSM-IV-TR47 to diagnose intellectual disabilities.

Epilepsy

Epilepsy diagnosis was based on Gunn and Fenton's 1969 operational definitionReference Gunn and Fenton48 in four studies.Reference Deb and Hunter25,Reference Deb and Hunter35,Reference Deb42,Reference Reid and Ballinger49 Five studiesReference Snoeijen-Schouwenaars, van Ool, Tan, Aldenkamp, Schelhaas and Hendriksen37,Reference Tyrrell, Cosgrave, McCarron, McPherson, Calvert and Kelly44,Reference Smith and Matson46,Reference Deb and Joyce50,Reference Tyrrell, Cosgrave, McLaughlin and Lawlor51 referred to the International League Against Epilepsy criteria.52,Reference Fisher, Acevedo, Arzimanoglou, Bogacz, Cross and Elger53

Psychiatric disorders

The methods used to define and assess psychiatric disorders differed across the selected studies. Seven studies used a retrospective design and collected data from case notes.Reference Deb and Joyce50,Reference Collacott54–Reference Turkistani59 Four studiesReference Arshad, Winterhalder, Underwood, Kelesidi, Chaplin and Kravariti27,Reference Cowley, Holt, Bouras, Sturmey, Newton and Costello28,Reference Deb and Joyce50,Reference Turkistani59 assessed psychiatric disorders based on ICD-10 criteria,45 and two other studiesReference Deb and Hunter25,Reference Deb42 used the DSM-III-R.60

Of the studies that used validated instruments, threeReference Cooper, Smiley, Morrison, Allan, Williamson and Finlayson11,Reference Espie, Watkins, Curtice, Espie, Duncan and Ryan30,Reference Reid, Smiley and Cooper36 used the Psychiatric Assessment Schedule for Adults with Developmental Disabilities Checklist (PAS-ADD)Reference Moss, Prosser, Costello, Simpson, Patel and Rowe61 and oneReference Turky, Felce, Jones and Kerr62 used the short version of the tool (mini PAS-ADD).Reference Prosser, Moss, Costello, Simpson, Patel and Rowe63 Only one studyReference Deb, Thomas and Bright10 used a stringent epidemiological methodology by using a three-stage process for diagnosis. In stage 1, the authors screened the sample with the mini PAS-ADD interview.Reference Prosser, Moss, Costello, Simpson, Patel and Rowe63 Those who met caseness criteria according to the mini PAS-ADD interviewReference Prosser, Moss, Costello, Simpson, Patel and Rowe63 were further interviewed in stage 2, using the full PAS-ADD interview.Reference Moss, Patel, Prosser, Goldberg, Simpson and Rowe64 In stage 3, information from the full PAS-ADD interview was used to make a psychiatric diagnosis according to the ICD-10 criteria.Reference Smith and Matson46 One study each used the Diagnostic Assessment for the Severely Handicapped-II,Reference Fitzgerald, Matson and Barker31,Reference Sevin, Matson, Williams and Kirkpatrick-Sanchez65 the Psychopathology Instrument for Mentally Retarded AdultsReference Matthews, Weston, Baxter, Felce and Kerr26,Reference Matson, Kazdin and Senatore66 and the Autism Spectrum Disorders-Comorbidity for Adults.Reference Smith and Matson46,Reference Matson, Terlonge and Gonzalez67

Two studiesReference Deb and Hunter35,Reference Reid and Ballinger49 used the Standardized Assessment of PersonalityReference Mann, Jenkins, Cutting and Cowen68 to evaluate personality disorders, and two studiesReference Tyrrell, Cosgrave, McCarron, McPherson, Calvert and Kelly44,Reference Tyrrell, Cosgrave, McLaughlin and Lawlor51 used the Test for Severe ImpairmentReference Albert and Cohen69 and the Down's Syndrome Mental Status ExaminationReference Haxby70 to evaluate dementia. To evaluate anxiety and depressive disorders, two studiesReference Snoeijen-Schouwenaars, van Ool, Tan, Aldenkamp, Schelhaas and Hendriksen37,Reference Hermans and Evenhuis71 used the Anxiety, Depression, And Mood Scale,Reference Esbensen, Rojahn, Aman and Ruedrich72 with one studyReference Hermans and Evenhuis71 also using the PAS-ADD interviewReference Moss, Patel, Prosser, Goldberg, Simpson and Rowe64 for diagnosis of anxiety disorders.

Statistical methods used

Descriptive statistics, χ 2-test, logistic regression analysis and univariate and multivariate regression analyses were used.

Outcome

The overall rate of psychiatric disorders

We identified 11 controlled studies that compared the rate of psychiatric disorder in epilepsy and non-epilepsy groups, sevenReference Deb, Thomas and Bright10,Reference Matthews, Weston, Baxter, Felce and Kerr26,Reference Dunham, Kinnear, Allan, Smiley and Cooper29–Reference Lund32,Reference Mantry, Cooper, Smiley, Morrison, Allan and Williamson34 of which showed no significant inter-group difference between epilepsy and non-epilepsy groups. Two studiesReference Deb and Hunter25,Reference Cowley, Holt, Bouras, Sturmey, Newton and Costello28 showed a significantly higher rate of psychiatric disorders in the non-epilepsy group. One studyReference McGrother, Bhaumik, Thorp, Hauck, Branford and Watson33 reported a significantly higher rate of psychiatric disorders in the epilepsy group, and another showed a higher rate of psychological symptoms (as opposed to psychiatric disorders) in the epilepsy group compared with the non-epilepsy control groupReference McGrother, Bhaumik, Thorp, Hauck, Branford and Watson33 (see Tables 1 and 4). The findings of the studies published since 2010 (see Table 4) are similar to those that were published before 2010.

Rates of different types of psychiatric disorders

Tables 2 and 4 present data from 18 studies that reported rates of different types of psychiatric disorders.

Regarding psychotic disorders, two studiesReference Cooper, Smiley, Morrison, Allan, Williamson and Finlayson11,Reference Pawar and Akuffo57 showed significantly lower rates of psychosis in the epilepsy group compared with the non-epilepsy control group, whereas two studiesReference Turkistani59,Reference Turky, Felce, Jones and Kerr62 did not find a significant inter-group difference in the rate of psychosis and psychotic symptom scores. Two studiesReference Arshad, Winterhalder, Underwood, Kelesidi, Chaplin and Kravariti27,Reference Cowley, Holt, Bouras, Sturmey, Newton and Costello28 showed a significantly lower rate of schizophrenic spectrum disorders in the epilepsy group compared with the non-epilepsy group. One studyReference Deb and Hunter25 found a non-statistically significant higher rate of schizophrenia in the epilepsy group compared with the non-epilepsy control group.

Concerning depressive disorders, four studiesReference Deb and Hunter25,Reference Arshad, Winterhalder, Underwood, Kelesidi, Chaplin and Kravariti27,Reference Pawar and Akuffo57,Reference Turkistani59 showed lower rates of depression in the epilepsy group compared with the non-epilepsy controls, whereas two studies showed significantly higher scores of depressive symptoms in the epilepsy group.Reference Smith and Matson46,Reference Turky, Felce, Jones and Kerr62

Concerning anxiety disorders, two studies showed higher rates in the epilepsy group compared with the non-epilepsy group. In the first study,Reference Deb and Hunter25 the difference was not statistically significant, and in the second study,Reference Pawar and Akuffo57 statistical significance was not reported. One studyReference Arshad, Winterhalder, Underwood, Kelesidi, Chaplin and Kravariti27 showed lower rates in the epilepsy group compared with the non-epilepsy control group. Three studiesReference McGrother, Bhaumik, Thorp, Hauck, Branford and Watson33,Reference Reid, Smiley and Cooper36,Reference Turky, Felce, Jones and Kerr62 showed no statistically significant inter-group difference in anxiety disorders between epilepsy and non-epilepsy groups.

As for dementia, four studiesReference Tyrrell, Cosgrave, McCarron, McPherson, Calvert and Kelly44,Reference Tyrrell, Cosgrave, McLaughlin and Lawlor51,Reference Collacott54,Reference McCarron, McCallion, Reilly and Mulryan56 found a statistically significant association between dementia and epilepsy. All these studies included participants with Down syndrome. One studyReference McCarron, Gill, McCallion and Begley55 reported specifically on the rate of Alzheimer's disease, and found that epilepsy is significantly more common in those with Alzheimer's disease compared with those without the condition. Three other studiesReference Deb and Hunter25,Reference Arshad, Winterhalder, Underwood, Kelesidi, Chaplin and Kravariti27,Reference Turky, Felce, Jones and Kerr62 presented data related to dementia, but not specifically on participants with Down syndrome. In these studies, inter-group differences were not significant.

Regarding personality disorders, two studiesReference Deb and Hunter35,Reference Reid and Ballinger49 showed no significant difference between the epilepsy group and non-epilepsy control group, and one studyReference Arshad, Winterhalder, Underwood, Kelesidi, Chaplin and Kravariti27 showed lower rates of personality disorders in adults with intellectual disabilities and epilepsy compared with the non-epilepsy group; the significance level was not reported.

Association between psychiatric disorders and epilepsy-related variables

Association between overall and/or specific types of psychiatric disorders and epilepsy-related variables has been reported in various studies (see Tables 3 and 4).

Four studies investigated the relationship between seizure types such as focal versus generalised seizures, and rates of psychiatric disorders. None reported a significant association.Reference Lund32,Reference Snoeijen-Schouwenaars, van Ool, Tan, Aldenkamp, Schelhaas and Hendriksen37,Reference Deb and Joyce50,Reference Ring, Zia, Lindeman and Himlok58

On the other hand, epileptic activity was significantly associated with overall psychiatric disorders in two studies.Reference Deb and Hunter25,Reference Espie, Watkins, Curtice, Espie, Duncan and Ryan30 One studyReference Lund32 showed a significantly higher rate of psychiatric disorders in the active epilepsy group (seizure in the past 12 months) than the non-epilepsy control group. Active epilepsy, characterised by having at least one seizure in the past 3 monthsReference Ring, Zia, Lindeman and Himlok58 or at least one seizure in the past 12 months,Reference Deb and Hunter35 was respectively associated with lower rates of psychosis and depressive disorders in one study,Reference Ring, Zia, Lindeman and Himlok58 and with higher rates of personality disorders in another study.Reference Deb and Hunter35

Two studies investigated electroencephalogram (EEG) activities associated with overall psychiatric disorders. One study showed higher rates of psychiatric disorders in those whose EEG showed epileptiform changes compared with those whose EEG did not show epileptiform changes,Reference Deb and Joyce50 and one studyReference Deb42 showed lower rates of psychiatric disorders in those whose EEG showed epileptiform changes compared with those whose EEG showed excessive background slowing activity. One study showed significantly higher rates of personality disorders in those whose EEG showed epileptiform changes compared with those whose EEG showed excessive background slowing.Reference Deb42

Regarding seizure frequency, one studyReference Deb and Hunter25 found significantly lower rates of psychiatric disorders in those with frequent seizures compared with a control group of adults with intellectual disabilities alone (no epilepsy). One studyReference Turkistani59 showed a significant positive association between seizure frequency and depression, and one studyReference Snoeijen-Schouwenaars, van Ool, Tan, Aldenkamp, Schelhaas and Hendriksen37 found that lower levels of anxiety were significantly associated with a high seizure frequency in adults with intellectual disabilities.

One studyReference Espie, Watkins, Curtice, Espie, Duncan and Ryan30 reported a significant association between psychiatric disorders and seizure severity.

Polypharmacy of anti-epileptic medications was significantly associated with less psychiatric disorders compared with the intellectual disabilities only control group,Reference Deb and Hunter25 with a higher score of personality disordersReference Deb and Hunter35 and lower levels of anxietyReference Snoeijen-Schouwenaars, van Ool, Tan, Aldenkamp, Schelhaas and Hendriksen37 compared with those receiving mono-therapy of anti-epileptic medication.

Psychiatric disorders and the level of intellectual disabilities

Higher rates of psychiatric disorders were found in adults with mild-to-moderate intellectual disabilities compared with adults with severe-to-profound intellectual disabilities in four studies.Reference Deb and Hunter25,Reference Lund32,Reference Reid, Smiley and Cooper36,Reference Deb and Joyce50 The same association was found when investigating psychotic disorders in two studies.Reference Deb and Hunter25,Reference Ring, Zia, Lindeman and Himlok58 Concerning depressive disorders, one studyReference Ring, Zia, Lindeman and Himlok58 showed lower rates in those with mild intellectual disabilities compared with severe intellectual disabilities in the group of participants with non-active epilepsy. Another studyReference Snoeijen-Schouwenaars, van Ool, Tan, Aldenkamp, Schelhaas and Hendriksen37 found that depressive symptoms were associated with more severe levels of intellectual disabilities, but found no association between anxiety symptoms and severity of intellectual disabilities. However, one studyReference Reid, Smiley and Cooper36 showed that anxiety symptoms were more frequent in adults with mild intellectual disabilities compared with adults with severe intellectual disabilities.

Meta-analysis

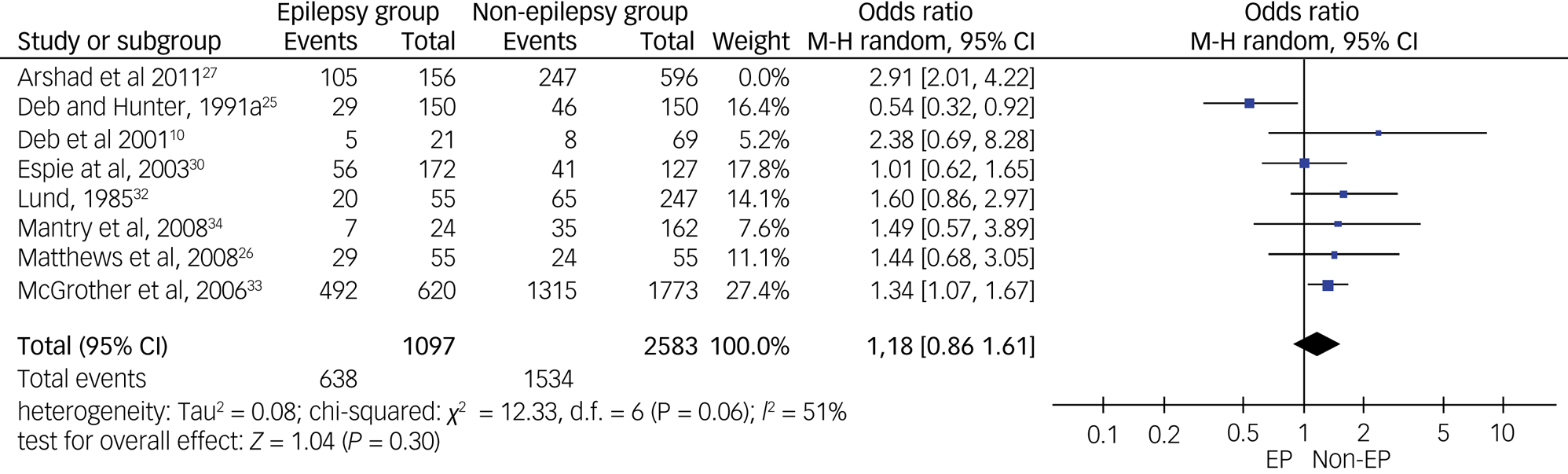

For overall psychiatric disorders, relevant data for meta-analysis were available from only eight out of the 11 controlled studies. Using a random-effects meta-analysis, pooled odds ratio data from these eight studies showed no significant inter-group difference (P = 0.09), but the heterogeneity level was high (I 2 = 76%, P < 0.01) (see Fig. 2). After the sensitivity check, we have removed data from one study that produced the highest level of heterogeneity and a high risk of bias according to the Cochrane risk of bias tool. This reduced heterogeneity to a borderline moderate level (I 2= 51%, P = 0.06). The final meta-analysis from the pooled data from seven studies shows a pooled odds ratio of 1.18 (95% CI 0.86–1.61, P = 0.06), using the random-effects model (see Fig. 3). This finding suggests the absence of a statistically significant difference in the rate of overall psychiatric disorders between the epilepsy and non-epilepsy control groups.

Fig. 2 Forest plot of eight studies on overall psychiatric disorders before sensitivity analysis.

M-H: Mantel-Haenszel method; EP: Epilepsy.

Fig. 3 Forest plot of data from seven studies on overall psychiatric disorders after sensitivity analysis.

M-H: Mantel-Haenszel method; EP: Epilepsy.

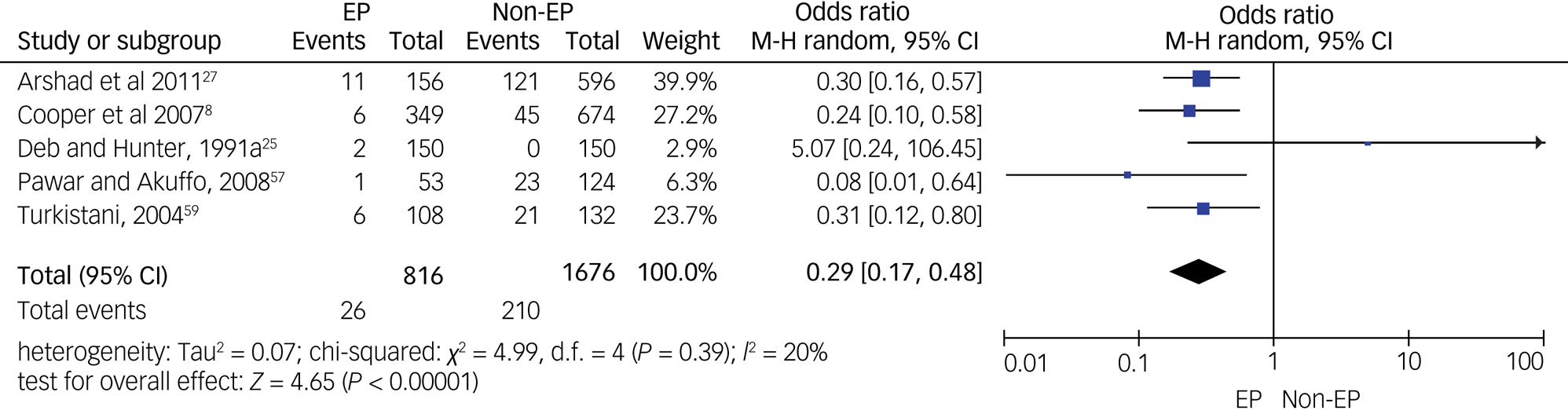

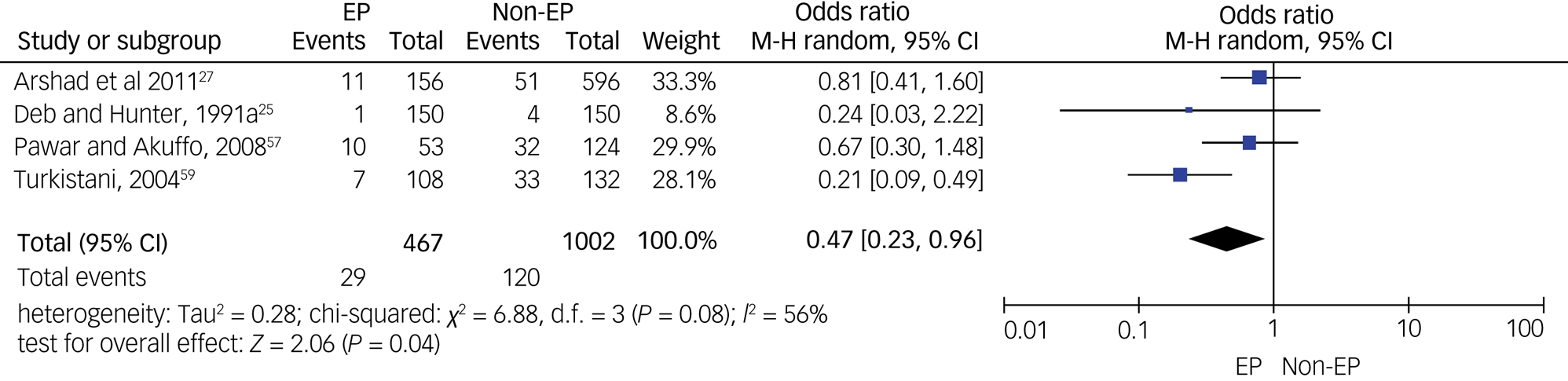

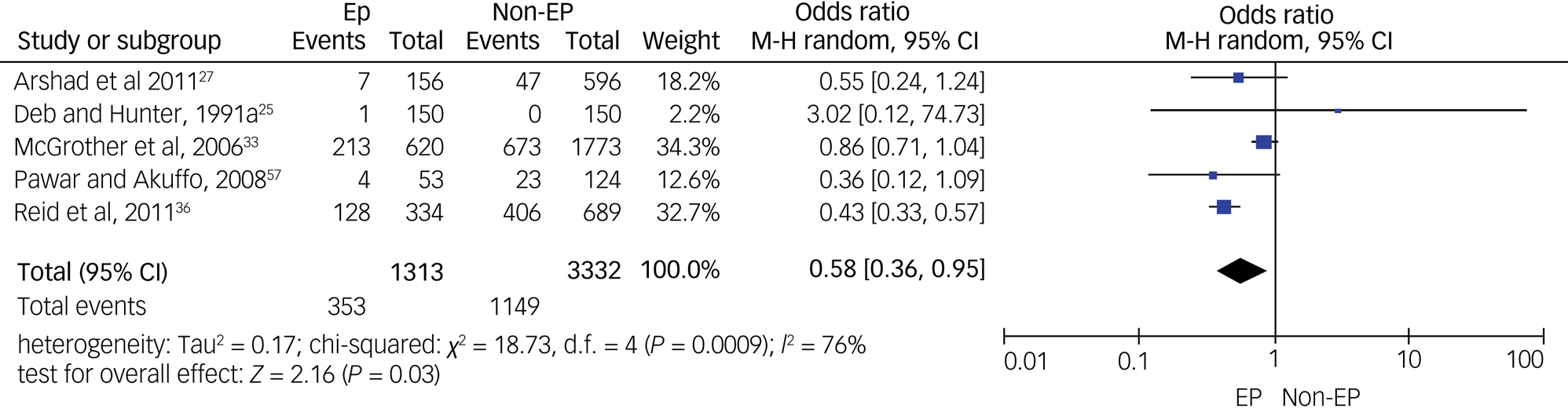

As for specific types of psychiatric disorders, we pooled data on psychotic disorders from five studies (see Fig. 4), on depressive disorders from four studies (see Fig. 5) and on anxiety disorders from five studies (see Fig. 6). A meta-analysis of five studies on psychotic disorders showed a statistically significant higher rate in the non-epilepsy control group compared with the epilepsy group, with a small effect size of 0.29 (95% CI 0.17–0.48, P < 0.01). The heterogeneity level was low (I 2= 20%, P = 0.29). Depressive disorders meta-analysis of four studies showed a statistically significant higher rate in the non-epilepsy control group compared with the epilepsy group, with a moderate effect size of 0.47 (95% CI 0.23–0.96, P = 0.04). The heterogeneity level was high, but <60% (I 2= 56%, P = 0.08). Meta-analysis of data on anxiety disorders from five studies also showed a significantly higher rate in the non-epilepsy control group compared with the epilepsy group, with a moderate effect size of 0.58 (95% CI 0.36–0.95, P = 0.03). The level of heterogeneity between studies was substantial (I 2= 79%, P < 0.001).

Fig. 4 Forest plot of data from five studies on psychotic disorders.

M-H: Mantel-Haenszel method; EP: Epilepsy.

Fig. 5 Forest plot of data from four studies on depressive disorders.

M-H: Mantel-Haenszel method; EP: Epilepsy.

Fig. 6 Forest plot of data from five studies on anxiety disorders.

M-H: Mantel-Haenszel method; EP: Epilepsy.

Quality control

Five studies were assessed as of high quality, based on the SIGN 50 checklist.

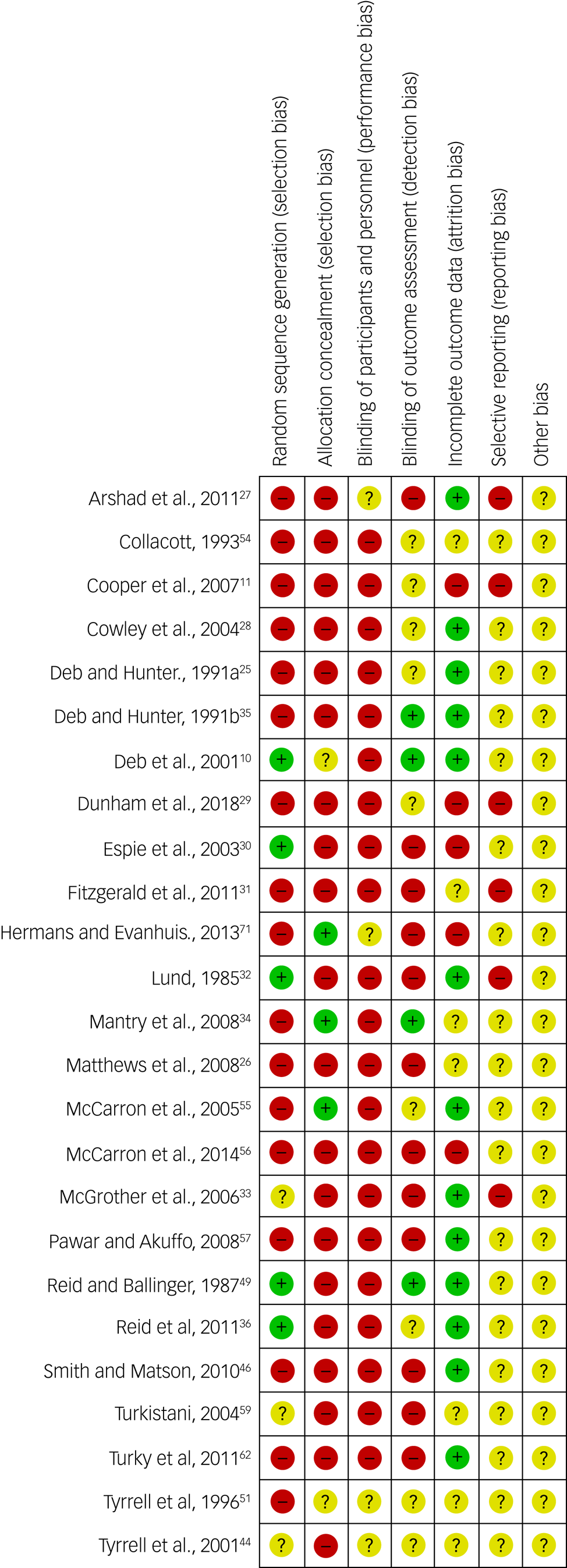

Twenty-five controlled studies presenting data on overall and specific psychiatric disorders were assessed with the Cochrane risk of bias tool. A high risk of selection and reporting bias was reported for most studies (see Fig. 7). A summary graph for the risk of bias is presented in Supplementary Appendix 4.

Fig. 7 Cochrane risk of bias summary figure for 25 controlled studies.

Red with minus sign = high risk of bias; Yellow with exclamation point = unknown risk of biais; Green with plus sign = low risk of bias

A funnel plot for overall psychiatric disorders, supported by Egger's test, suggests an absence of publication bias (P = 0.97). Regarding psychotic disorders, depressive disorders and anxiety disorders, funnel plots and Egger's tests suggest an absence of publication bias (P = 0.63, P = 0.53 and P = 0.72, respectively). Of the included studies in this review, 31% reported receiving external funding.

This systematic review/meta-analysis is of a high standard, based on the AMSTAR 2 checklist (see Supplementary Appendix 2).

Discussion

The purpose of our systematic review was to explore whether there is an association between epilepsy and psychiatric disorders in adults with intellectual disabilities. We included 29 articles that met eligibility criteria.

A previous systematic reviewReference van Ool, Snoeijen-Schouwenaars, Schelhaas, Tan, Aldenkamp and Hendriksen15 included only two studies specifically on psychiatric disorders in people with intellectual disabilities. They missed several important studies that we have included in the current systematic review. They did not carry out a meta-analysis. We have included a much higher number of participants within the included studies (N = 9594) compared with the previous systematic review (N = 7742).Reference van Ool, Snoeijen-Schouwenaars, Schelhaas, Tan, Aldenkamp and Hendriksen15

The overall rate of psychiatric disorders

For meta-analysis, it was possible to pool data on the overall rate of psychiatric disorders from eight out of 11 controlled studies. After sensitivity analysis, we excluded data from one study that produced a high heterogeneity. A meta-analysis of the pooled data from the remaining seven studies did not show any significant inter-group difference in the rate of overall psychiatric disorders between the epilepsy and non-epilepsy groups. This finding is similar to that of the previous systematic review.Reference van Ool, Snoeijen-Schouwenaars, Schelhaas, Tan, Aldenkamp and Hendriksen15 A funnel plot and Egger's test showed no publication bias among the included studies. The recent publications did not show any different findings from the ones published before 2010.

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis comparing the rates of psychiatric disorders in epilepsy and non-epilepsy groups of adults with intellectual disabilities. No statistically significant inter-group difference was observed. However, this finding needs to be interpreted with caution, as the included studies are heterogeneous in terms of the definition of psychiatric disorders and instruments used to detect them; although individually most studies showed no significant inter-group difference. To minimise heterogeneity, we have used a sensitivity analysis, and because of different study designs, we have used a random-effects analysis. Also, the Cochrane risk of bias tool deemed most studies to be of poor quality. However, it is worth remembering that Cochrane assessment is designed for intervention studies, particularly randomised controlled trials, and none of the included studies were an intervention study. The main problem with the included studies is that apart from two, none included a matched control group for comparison. Of the two that included a matched control group, one showed a significantly higher rate of psychiatric disorders in the non-epilepsy group, and the other did not show any statistically significant inter-group difference.

Many factors affect the rate of psychiatric disorders in adults with epilepsy, including (a) underlying brain damage, such as the location and severity of any deformity, tumour or abnormal electrical discharge in the brain; (b) epilepsy-related factors, such as certain epileptic syndromes and genetic syndromes, are prone to lead to more psychopathology; (c) seizure-related factors, such as the severity, type and frequency of seizures; (d) anti-epileptic medication-related factors, such as the adverse effects of certain anti-epileptic medications and drug–drug interactions; and (e) psychosocial factors, such as loss of occupation, financial problems, lack of support and locus of control being outside the person so that the person does not have any control over the timing of seizure.Reference Deb, Jacobson, Mulick and Rojahn4 Included studies did not control for these confounding factors. Therefore, it is difficult to know the weighted influence of these factors on the rate of psychiatric disorders reported in different studies. Where data were available, the studies showed a higher rate of psychiatric disorders among adults with less severe intellectual disabilities. This may reflect the fact that psychiatric disorder is difficult to diagnose among adults with more severe intellectual disabilities.Reference Hemmings, Obousy and Craig73

Psychotic disorders

Our meta-analysis showed a significantly higher rate of psychosis among the non-epilepsy group compared with the epilepsy group. Psychosis is significantly more prevalent in adults with intellectual disabilities compared with the general population,Reference Hemmings, Obousy and Craig73 possibly because of common aetiology involving genetics and environmental factors.Reference Owen, O'Donovan, Thapar and Craddock74 For example, velocardiofacial (22q11.2 deletion) syndrome, a genetic disorder that causes intellectual disabilities, is associated with a high rate of psychosis.Reference Murphy75 Similarly, the maternal obstetric complication is a common risk factor for both intellectual disabilities and psychosis.Reference Clark, Kelley and Matson76 Psychosis is impossible to diagnose among adults with severe and profound intellectual disabilities.Reference Deb, Matthews, Holt and Bouras14 Symptoms of psychosis may be different when epilepsy is present. For example, some suggested that delusions and hallucinations may be unusual and atypical in the general population when associated with epilepsy.Reference Trimble77 If that is the case, it would be even more difficult to detect psychosis in some adults with intellectual disabilities in the presence of epilepsy. A higher rate of psychosis was associated with a milder form of intellectual disabilities. This may reflect the fact that psychosis is difficult to diagnose among adults with more severe intellectual disabilities.Reference Hemmings, Obousy and Craig73 There may be several reasons for this. For example, the neuronal networks necessary for the production of psychotic symptoms may be damaged or may not exist in adults with severe intellectual disabilities. It is not possible to assess reality-testing reliably in adults with severe intellectual disabilities. There are no valid tools available to diagnose psychosis in an adult with severe or profound intellectual disabilities.

Depressive disorders

Our meta-analysis showed a significantly lower rate of depressive disorders in the epilepsy group compared with non-epilepsy group, with a small effect size. Many psychosocial factors that are associated with epilepsy can precipitate depression, yet none of the included studies controlled for these potential confounding variables. The rate of depression could have been affected by the use of mood-stabilising anti-epileptics among some of the participants. Some studies suggested that depression may have an atypical manifestation in epilepsy.Reference Mula, Yogarajah, Agrawal, Faruqui and Bod78 If that is the case, it would be even more difficult to diagnose depression in many adults with intellectual disabilities. Where data were available, depression was shown to be more common among adults with a severe intellectual disabilities. This may reflect the fact that depressive disorders may be diagnosed relatively easily among those with severe intellectual disabilities, as the diagnosis is more dependent on observable symptoms, such as sleep disorder and change in appetite.Reference Hemmings, Obousy and Craig73

Anxiety disorders

Our meta-analysis has shown a significantly lower rate of anxiety disorders in the epilepsy group with intellectual disabilities compared with the non-epilepsy group with intellectual disabilities, although the effect size was small. Therefore, this difference may not be clinically significant. However, some anti-epileptic medications may improve anxiety symptoms.Reference Snoeijen-Schouwenaars, van Ool, Tan, Aldenkamp, Schelhaas and Hendriksen37,Reference Brodie, Besag, Ettinger, Mula, Gobbi and Comai79

Anxiety is a common symptom in adults with intellectual disabilities. Any change in routine is likely to cause anxiety in this population. The subjective feelings of anxiety, such as palpitation, a sinking feeling and ‘butterflies in the stomach’, are difficult to detect in many adults with intellectual disabilities who cannot communicate their feelings and thoughts. Anxiety may manifest as a problem behaviour in adults with intellectual disabilities, and therefore is not diagnosed as a psychiatric disorder.Reference Deb, Matthews, Holt and Bouras14,Reference Hemmings, Obousy and Craig73 It is difficult to draw any definitive conclusion from this finding because the number of studies included in the meta-analysis is small, and each included a small number of participants.

Personality disorders

We included three studies on personality disorder, none of which showed any statistically significant inter-group difference. Diagnosis of personality disorder is controversial among adults with intellectual disabilities.Reference Moher, Shamseer, Clarke, Ghersi, Liberati and Petticrew18 The relationship between personality disorder and epilepsy is controversial, and standard assessment tools, such as Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory,Reference Hathaway and McKinley80 have been criticised for not being the right instrument to detect personality disorders in adults with epilepsy in the general population.Reference Trimble81 As a result, Bear and FedioReference Bear and Fedio82 have proposed a specific personality trait related to focal epilepsy of temporal lobe origin. Therefore, the studies included in this review may not be reliable in terms of the validity of personality disorder diagnosis.

Dementia

All five included studies on dementia showed a statistically significant higher rate of dementia in the epilepsy group compared with the non-epilepsy group. Epilepsy is a common feature of dementia, particularly in the late stage.Reference Noebels83 All five studies included adults with Down syndrome. People with Down syndrome are particularly prone to developing dementia, and the age at onset is earlier than the general population.Reference Deb, Salehi, Rafii and Phillips84 Therefore, the significant association between dementia and epilepsy found in this review is not unexpected. However, the positive association between epilepsy and dementia seems specific to people with Down syndrome and older adults with intellectual disabilities. However, it is worth keeping in mind that one may expect cognitive decline in patients with severe uncontrolled seizures, as a result of ongoing seizure activities and/or head trauma sustained during the seizures.

Epilepsy-related factors

Included studies that assessed epilepsy-related factors, such as seizure types, active versus non-active epilepsy, seizure frequency/severity, epileptiform changes in the EEG and polypharmacy of anti-epileptic medications, did not find a clear association between the rate of psychiatric disorders and these variables. Subgroup comparisons do not provide adequate power to detect a clinically significant difference because of the small number of participants involved in each subgroup and the lack of control groups. It will be necessary to conduct a larger randomised controlled trial to recruit a reasonable number of participants in each subgroup, to provide adequate power to detect clinically significant inter-group differences.

Clinical implications

The clinical implications of our findings are manyfold. First, it is not known whether this association is causally related. The underlying brain damage in adults with severe and profound intellectual disabilities, and psychosocial factors in adults with mild intellectual disabilities, may be stronger determinants of psychiatric disorders in adults with intellectual disabilities than epilepsy per se.Reference Dunham, Kinnear, Allan, Smiley and Cooper29 Some anti-epileptic medications, such as topiramate, may produce psychotic symptoms.Reference Brodie, Besag, Ettinger, Mula, Gobbi and Comai79 Others, such as lamotrigine and sodium valproate, may have a protective effect against affective disorders. The relationship between anxiety and epilepsy is complex. Although anxiety may be a presenting symptom during the prodrome, pre-ictal, ictal and post-ictal phase, particularly in focal seizures of temporal or frontal lobe origin, anxiety can also precipitate an epileptic seizure. Although the peri-ictal manifestation of psychiatric symptoms is more common, this has not been assessed in the studies included in this review. Sometimes an improvement in seizure control may worsen mental state in adults with intellectual disabilities, but the opposite may also be the case.Reference Trimble81 The use of antipsychotic medication is common in this population,85 which itself may lead to psychiatric symptoms or precipitate seizures. As psychiatric symptoms are precipitated by a complex interaction between internal and external factors, a thorough multi-agency assessment of mental state, using a biopsychosocial model, is essential for the appropriate management of psychiatric disorders and epilepsy in adults with intellectual disabilities.

Strengths

There are several strengths to our study. We have conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis on psychiatric disorders in an adult population of people with intellectual disabilities and epilepsy, which has not previously been done. Our review received a high score on AMSTAR 2 quality control check for systematic reviews, as we have complied with all their requirements (see Supplementary Appendix 2). Further, we have assessed the risk of bias with SIGN 50 and the Cochrane risk of a bias tool, and included a comprehensive Cochrane risk of bias graph (see Supplementary Appendix 4) and figure (see Fig. 7), which was not done by the other systematic review. Our systematic review has been registered with the well-established PROSPERO database for our protocol to be available for public scrutiny. Finally, we carried out an extensive hand-search of journals in the field of epilepsy and intellectual disabilities, along with rigorous cross-referencing.

Limitations

There are several limitations to our study. Although a rigorous literature search method was used, it is still possible to have missed some relevant papers. Also, grey literature and abstracts only were excluded, as they would not fit our eligibility criteria and risk of bias assessment.

It is difficult to pool data for meta-analysis from such heterogeneous studies, although individually most of them showed no association between epilepsy and psychiatric disorders in adults with an intellectual disabilities. Although our sensitivity analysis reduced the heterogeneity to an acceptable level, the fact remains that many different instruments and definitions were used for psychiatric diagnosis in included studies. Diagnostic classification systems have changed over time, and different studies have used differing criteria for diagnosing intellectual disabilities and psychiatric disorders. There is a high level of bias caused by the absence of an appropriately matched control group in most included studies. Therefore, to draw a definitive conclusion about the relationship between psychiatric disorders and epilepsy in adults with an intellectual disabilities, it is necessary to carry out more methodologically sound studies in future, using appropriately matched control groups and standardised instruments to detect and define psychiatric disorders in this population.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.55.

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Acknowledgements

B.L. is funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Research for Patient Benefit programme (grant number PBPG-0817–20010). The Imperial Biomedical Research Centre Facility, which is funded by the NIHR, provided support for the study. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Author contributions

B.A.B. and S.D. conceptualised and designed the study. B.A.B. carried out the literature search. B.A.B. and B.L. screened bibliographies and extracted data, and completed the risk of bias checklist. B.L. carried out a meta-analysis. All authors contributed to manuscript writing and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.