Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a psychiatric disorder characterised by pervasive instability in affect regulation, impulse control, interpersonal relationships and self-image. It is associated with severe psychological impairment and a high risk of suicide.Reference Lieb, Zanarini, Schmahl, Linehan and Bohus 1 The prevalence of BPD is estimated to be 1–2% in the general population, with a female to male ratio of 3:1. 2 – Reference Widiger and Weissman 4 While childhood sexual abuse is neither necessary nor sufficient for development of BPD, 40–71% of patients with BPD report a history of childhood sexual abuse.Reference Lieb, Zanarini, Schmahl, Linehan and Bohus 1 Heritability of the disorder is estimated to be 47%.Reference Lieb, Zanarini, Schmahl, Linehan and Bohus 1 Neurobiologically, there is evidence that individuals with BPD have altered functioning in multiple regions of the brain including the anterior cingulate gyrus, hippocampus, amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex, as such BPD is conceptualised as decreased prefrontal inhibitory control and amygdala hyperactivity.Reference Lieb, Zanarini, Schmahl, Linehan and Bohus 1 It has been shown that individuals with BPD access health resources more than those with other psychiatric disorders.Reference Bender, Dolan, Skodol, Sanislow, Dyck and McGlashan 5

Fibromyalgia is a syndrome characterised by widespread pain, abnormal pain processing, sleep disturbance, fatigue and psychological distress.Reference Clauw 6 , Reference Mease 7 The aetiology of fibromyalgia remains unknown; however, there are often characteristic alterations in sleep pattern and changes in neuroendocrine transmitters such as serotonin, substance P, growth hormone and cortisol that suggest that the pathophysiology of the syndrome may be associated with autonomic and neuroendocrine regulation.Reference Jahan, Nanji, Qidwai and Qasim 8 Central sensitisation, dampening of inhibitory pain pathways and changes in neurotransmitters can lead to abnormal processing of sensory signals in the central nervous system, as such lowering the pain threshold and amplifying sensory signals causing constant pain.Reference Jahan, Nanji, Qidwai and Qasim 8 Frequent comorbidity of fibromyalgia and mood disorders suggests a role for the stress response and for neuroendocrine abnormalities in the disease process.Reference Jahan, Nanji, Qidwai and Qasim 8 The hypothalamic pituitary axis (HPA) is a critical component of the stress–adaptation response. In fibromyalgia, the stress–adaptation response is disrupted, leading to stress-induced symptoms.Reference Jahan, Nanji, Qidwai and Qasim 8 Patients with fibromyalgia also often suffer from comorbid anxiety disorders.Reference Fleming and Volcheck 9 They are also more likely to have histories of early-life physical or sexual abuse, neglect, family history of alcohol-use disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).Reference Frankenburg and Zanarini 10 Furthermore, personality has been suggested as an important factor in modulating a person's response to psychological stressors, and certain personalities may facilitate translation of these stressors to symptoms characteristic of fibromyalgia.Reference Malin and Littlejohn 11 The prevalence of fibromyalgia in the general population is approximately 2%, with women affected 10 times more than men.Reference Macfarlane, Thomas, Papageorgiou, Schollum, Croft and Silman 12

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is a condition characterised by 6 months or more of persisting or relapsing fatigue. The fatigue is not relieved by rest, nor explained by medical or psychiatric conditions, and it is accompanied by a range of cognitive and somatic symptoms.Reference Fukuda, Straus and Hickie 13 The pathophysiology of CFS remains unclear. However, research continues to point towards central nervous system involvement.Reference Cho, Skowera, Cleare and Wessely 14 A hyperserotonergic state and hypoactivity of the HPA have also been indicated, but it remains uncertain whether these are a cause of or consequence of CFS.Reference Cho, Skowera, Cleare and Wessely 14 Female gender genetic disposition, certain personality traits and physical and emotional stressors have been identified as risk factors.Reference Afari and Buchwald 15 , Reference Saez-Francas, Calvo, Alegre, Castro-Merrero, Ramirez and Hernadez-Vara 16 Moreover, exposure to childhood trauma has been found to increase the risk of CFS three- to eightfold.Reference Heim, Wagner, Maloney, Papanicolaou, Solomon and Jones 17 Prevalence of CFS in primary care setting ranges from 3 to 20%.Reference Lee, Yu, Wing, Chan, Lee and Lee 18 , Reference Davis, Khoshknabi and Yue 19

Comorbidity of BPD and fibromyalgia has been postulated. The disorders share common aetiological factors such as childhood trauma and preponderance in females, and they are observed to co-occur with similar psychiatric conditions such as depression, anxiety disorders and PTSD.Reference Sansone, Sansone and Rockne 20 There is also considerable clinical overlap between fibromyalgia and CFS. One study found that 21.2% of patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia also met criteria for CFS.Reference Sansone, Sansone and Rockne 20

Though the core features of fibromyalgia, CFS and BPD differ (pain v. fatigue v. emotional dysregulation), the overlap in aetiological factors and demographic characteristics in addition to our clinical observations of comorbidity compelled us to explore possible relationships between the disorders of interest. Our aim was to determine whether patients with fibromyalgia or CFS are more likely to suffer from BPD – and conversely, are patients with BPD more likely to suffer from fibromyalgia and CFS? We hypothesised that, since patients with BPD experience significant chronic stress related to interpersonal difficulties and emotional dysregulation, they would be more likely to suffer from CFS and/or fibromyalgia, two disorders which are believed to be related to maladaptive stress responses. If our hypothesis turned out to be true, those with BPD would be over-represented among samples of patients suffering from fibromyalgia or CFS.

Method

Data sources and terms used

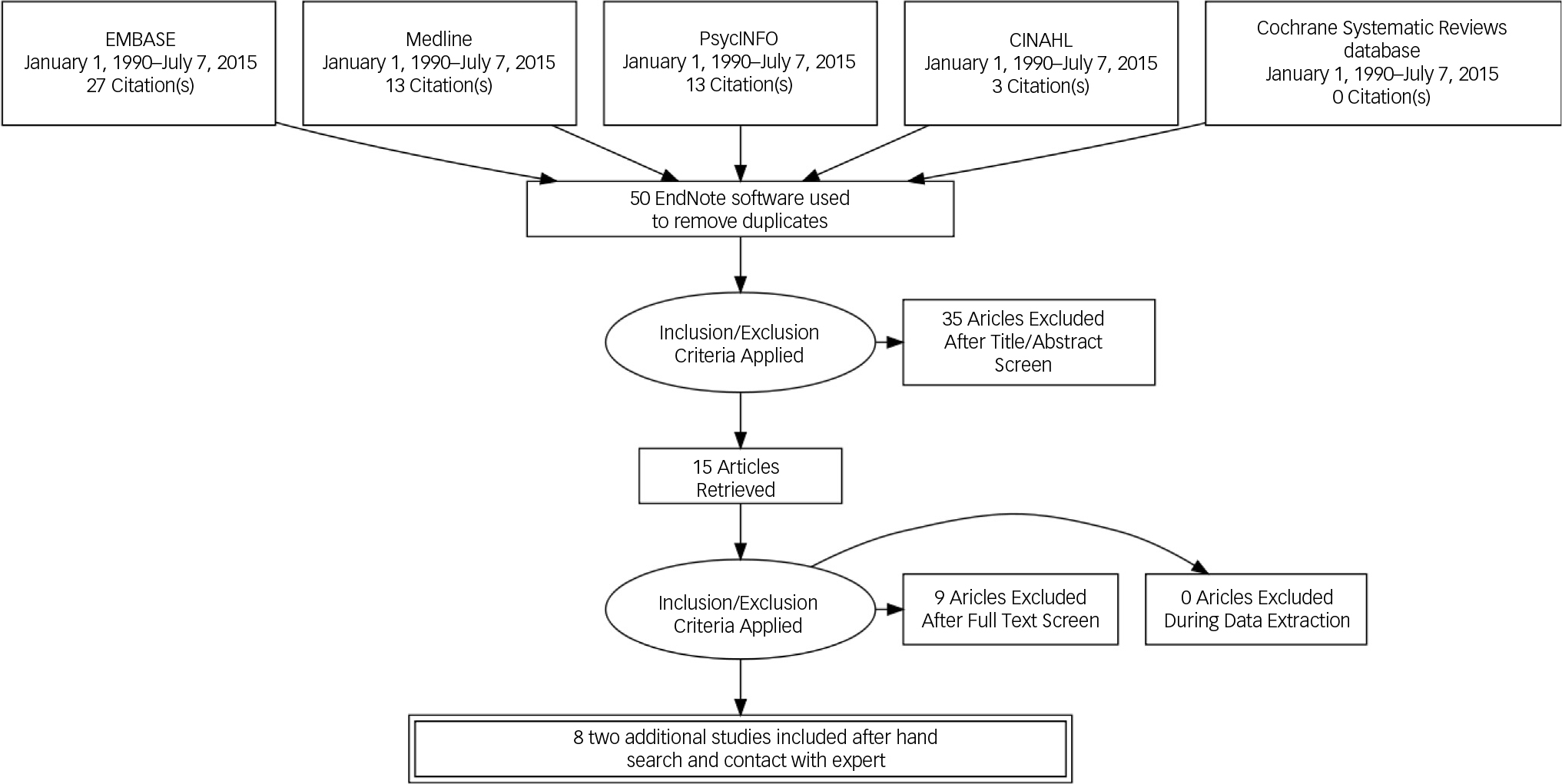

A literature search was conducted of EMBASE, Medline, PsycINFO, CINAHL and Cochrane Systematic Reviews databases for eligible studies. Search terms included fibromyalgia, CFS, personality disorder, Axis II, emotionally unstable personality disorder and BPD. Emotionally unstable personality disorder was included as a search term because it is the ICD-10 equivalent of BPD. The search included studies from 1 January 1990 – the year the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) published diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia – to 7 July 2015.

Study selection

Studies fulfilling the following criteria were included in this review: (1) examined the prevalence of fibromyalgia and/or CFS in patients with BPD, or examined prevalence of BPD in patients with fibromyalgia and/or CFS; (2) used valid criteria for diagnosis; (3) published in a peer-reviewed journal; 4) published in English or French.

The inclusion criteria were developed by the supervising author and reviewed by the co-authors.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from each study: country of study, publication year, number of participants, study setting (in-patient, out-patient/community), study design, gender distribution, mean age or age range of the participants, diagnostic criteria applied for BPD, fibromyalgia and CFS, and prevalence. The supervising author conducted data extraction. A meta-analysis could not be conducted due to heterogeneous characteristics of selected studies.

Results

The EMBASE, Medline, PsycInfo, CINAHL and Cochrane Systematic Reviews database searches identified 27, 13, 13, 3 and 0 studies, respectively. Study titles and abstracts were reviewed independently by all three co-authors, and 15 studies were identified as potentially relevant. These studies were reviewed in full by the supervising author, and nine were excluded, as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Six studies were found to be eligible for analysis in the systemic review. It was agreed that supervising author's decision would prevail in case of any potential disagreements. The supervising author subsequently conducted a hand search of the references of the six eligible studies, identifying one additional relevant study. An additional study was included after contact with an expert in the field (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Literature search strategy.

Table 1 lists the characteristics of studies assessing the prevalence of BPD in patients with fibromyalgia. All three studies used the ACR criteria for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III Personality Disorders (SCID-II). The 2004 study by Thieme et al evaluated the prevalence and predictors of psychiatric disorders in 115 women with fibromyalgia, and the authors found that 5.25% of participants met criteria for BPD.Reference Thieme, Turk and Flor 21 The 2009 study by Rose et al investigated the prevalence of Axis 1 and Axis II disorders among 30 patients with fibromyalgia referred to consultation psychiatry as a facet of treatment within a specialised pain consultation service. There, 16.7% of the patients met criteria for BPD.Reference Rose, Cottencin, Chouraki, Wattier, Houvenagel and Vallet 22 The 2010 study by Uguz et al examined the prevalence of Axis I and Axis II psychiatric disorders in 103 patients with fibromyalgia as compared with sociodemographically matched controls.Reference Uguz, Cicek, Salli, Karahan, Albayrak and Kaya 23 The prevalence of BPD was 1% in patients with fibromyalgia and 0% in control individuals, a non-statistically significant difference.Reference Uguz, Cicek, Salli, Karahan, Albayrak and Kaya 23

Table 1 Prevalence of borderline personality disorder in patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia

| Authors | Country of study | Year published | Participants with fibromyalgia (n) | Study setting/design |

Diagnostic criteria | Sex | Age (s.d.) | Prevalence of BPD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thieme et al Reference Thieme, Turk and Flor 21 | Germany | 2004 | 115 | Out-patient/case series | SCID-II*

ACR** |

100% female | 48.17 (10.32) |

5.25 |

| Rose et al Reference Rose, Cottencin, Chouraki, Wattier, Houvenagel and Vallet 22 | France | 2009 | 30 | Out-patient/case series | SCID-II*

MINI † ACR** |

73% female | 48.4 (9.5) |

16.7 |

| Uguz et al Reference Uguz, Cicek, Salli, Karahan, Albayrak and Kaya 23 | Turkey | 2010 | 103 | Out-patient/case control | SCID-II*

ACR** |

100% female | Not given | 1 |

* Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders

** American College of Rheumatology Criteria for Fibromyalgia

† Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview.

Table 2 lists the characteristics of studies assessing the prevalence of BPD in patients with CFS. Five studies were identified. All of the studies used the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) criteria for CFS and relied on self-report questionnaires such as the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire–Revised or 4th edition (PDQ-R, PDQ-IV) or the Assessment of DSM-IV Personality Disorders Questionnaire (ADP-IV) for diagnosis of personality disorders. The 1996 study by Johnson et al investigated the relative rates of personality disorders in patients with CFS, compared with patients with multiple sclerosis, control patients with depression and healthy controls.Reference Johnson, DeLuca and Natelson 24 The prevalence of BPD was found to be 17% in those with CFS, 25% in patients with multiple sclerosis, 29% in control patients with depression and 0% in healthy controls.Reference Johnson, DeLuca and Natelson 24 The 2009 study by Courjaret et al assessed the prevalence of personality disorders in a sample of female CFS patients compared with two control groups (psychiatric and general population controls).Reference Courjaret, Schotte, Wijnants, Moorkens and Cosyns 25 The study found that the prevalence of BPD was 2, 42 and 6% in the CFS, psychiatric and general population groups, respectively.Reference Courjaret, Schotte, Wijnants, Moorkens and Cosyns 25 The 2010 population-based study by Nater et al compared the prevalence of personality disorders and traits of survey respondents meeting criteria for CFS versus respondents with ‘insufficient fatigue’ and ‘well’ respondents. The authors found that the prevalence of BPD was 1.8% among those with CFS, 0.4% among those with fatigue who did not meet criteria for CFS and 0% among those identified as well.Reference Nater, Jones, Lin, Maloney, Reeves and Heim 26 The Kempke et al study published in 2012 assessed the prevalence of DSM-IV personality disorders among female patients with CFS, compared with ‘normal community individuals’ and ‘psychiatric patient’ controls.Reference Kempke, Van Den Eede, Schotte, Claes, Van Wambeke and Van Houdenhove 27 The prevalence of BPD was found to be 6.5% in patients with CFS, 6.5% in the community control group and 39.1% in the psychiatric patient control group.Reference Kempke, Van Den Eede, Schotte, Claes, Van Wambeke and Van Houdenhove 27 The 2015 study by Carvo et al assessed the prevalence of personality disorders among patients with CFS and found that 3.03% of the participants had a comorbid BPD diagnosis.Reference Calvo, Saez-Francas, Valero, Alegre and Casas 28

Table 2 Prevalence of borderline personality disorder in patients diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome

| Authors | Country of study | Year published | Participants with CFS (n) | Study setting/design |

Diagnostic criteria | Gender distribution | Age | Prevalence of BPD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Johnson et al Reference Johnson, DeLuca and Natelson 24 | USA | 1996 | 35 | Out-patient/case–control | CDC-CFS*

PDQ-R † |

88.6% female | 34.8 (s.e.m.=1.3) |

17 |

| Courjaret et al Reference Courjaret, Schotte, Wijnants, Moorkens and Cosyns 25 | Belgium | 2009 | 50 | Out-patient/case–control | CDC-CFS*

ADP-IV** |

100% female | 37.1 (s.d.=7.9) |

2 |

| Nater et al Reference Nater, Jones, Lin, Maloney, Reeves and Heim 26 | USA | 2010 | 113 | Community/survey | CDC-CFS*

PDQ-4 ‡ |

81.4% female | 44.3 | 1.8 |

| Kempke et al Reference Kempke, Van Den Eede, Schotte, Claes, Van Wambeke and Van Houdenhove 27 | Belgium | 2012 | 92 | Out-patient/case–control | CDC-CFS*

ADP-IV** |

100% female | 42.2 (s.d.=9.0) |

6.50 |

| Calvo et al Reference Calvo, Saez-Francas, Valero, Alegre and Casas 28 | Spain | 2015 | 132 | Hospital/cross-sectional | CDC-CFS*

PDQ-4 ‡ |

91.7% female | 47.7 (s.d.=9.1) |

3.03 |

* Centers for Disease Control chronic fatigue syndrome criteria

** Assessment of DSM-IV Personality Disorders Questionnaire

† Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire–Revised

‡ Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire 4th edition.

Discussion

In psychiatric clinical settings, comorbidity of BPD with fibromyalgia or CFS is observed. As there has not previously been a systematic review of the literature assessing the prevalence of BPD in patients with fibromyalgia or CFS, or the prevalence of fibromyalgia and CFS in patients with BPD, this study represents an important step to further our understanding of possible relationships between these conditions. It would be important to study the association considering the prognostic implications and potential treatment challenges inherent in these complex conditions. The study also presents an opportunity to identify potential gaps in evidence regarding these complicated disorders.

Fibromyalgia and CFS in patients with BPD

We did not identify any studies that specifically assessed the prevalence of fibromyalgia or CFS in patients with BPD. However, as a facet of their longitudinal study published in 2004, Frankenburg & Zanarini assessed the prevalence of ‘poorly understood medical syndromes’ – an umbrella term encompassing CFS, fibromyalgia and temporomandibular joint syndrome – in patients previously diagnosed with BPD.Reference Frankenburg and Zanarini 10 The medical syndromes were diagnosed on the basis of the Medical History and Services Utilization Interview (MHSUI). Among patients who did not remit from BPD, the prevalence of a poorly understood medical syndrome was 42.2%.Reference Frankenburg and Zanarini 10 Among patients who had remitted from BPD, the prevalence of a poorly understood medical syndrome was 25.0%, suggesting that there is a high prevalence of these complex syndromes not only in patients with BPD but also in patients who have remitted from BPD.Reference Frankenburg and Zanarini 10 Clearly, further study is needed to assess the prevalence of these specific syndromes in patients with BPD and in patients who have remitted from BPD.

BPD in patients with fibromyalgia

A small number of studies have assessed the prevalence of BPD among patients with fibromyalgia. All three studies reviewed in this study were conducted in tertiary out-patient clinic settings, and the prevalence rates in these populations, therefore, may not be generalisable to a wider population. There was wide variation in the reported prevalences (1 to 16.7%), and this variation may be partially explained by differences in geographical locations, demographic factors and study methodologies. Moreover, only the study by Uguz et al utilised a control group, and the difference in BPD prevalence between the fibromyalgia and control groups was not statistically significant.Reference Uguz, Cicek, Salli, Karahan, Albayrak and Kaya 23 The patients in the Rose et al study had all been referred to consultation–liaison psychiatry, and this may have selected for higher prevalences of all psychiatric diagnoses, including BPD.Reference Rose, Cottencin, Chouraki, Wattier, Houvenagel and Vallet 22 Finally, all three studies focused on current prevalence, as opposed to lifetime prevalence, of BPD, thus diminishing the likelihood of capturing instances where individuals with fibromyalgia have a previous history of BPD and have since remitted. At present, there does not appear to be firm and consistent evidence to support the hypothesis that the prevalence of BPD would be higher in individuals with fibromyalgia compared with the general population.

BPD in patients with CFS

A small number of studies have assessed the prevalence of BPD in CFS, and the rates of BPD and CFS comorbidity reported in these studies varied widely (1.8–17%). Again, this variability could be due to methodological, geographical and/or demographic differences across the studies. Of the three studies that compared the prevalence of BPD among patients with CFS with healthy controls, only one, the Johnson et al study, found a significantly higher rate of BPD among CFS sufferers (17% v. 0%).Reference Johnson, DeLuca and Natelson 24 Interestingly, the study by Courjaret et al found higher rates of BPD among healthy controls compared with individuals meeting criteria for CFS.Reference Courjaret, Schotte, Wijnants, Moorkens and Cosyns 25 In all five studies reviewed, current prevalence, rather than lifetime prevalence, of BPD was assessed. Therefore, the studies may not have captured instances where CFS sufferers had previously met criteria for, and subsequently remitted from, BPD. There does not appear to be firm and consistent evidence to support the hypothesis that the prevalence of BPD is higher in individuals with CFS than in the general population.

Limitations

This study was limited by the fact that we confined the literature search to studies published in English or French. Selection bias would be another limitation of the study as studies published in peer-reviewed journals were included, and it was difficult to search for unpublished observational studies. We did not include well-defined, objective quality assessments of reviewed studies. However, considering the paucity of relevant research studies, we do not believe that this would have significantly altered the findings and conclusions in this study.

Even with the limitations described above, this study examined potential relationships between clinically relevant comorbidities through careful analysis of available research. It would be reasonable to conclude that, considering the marked heterogeneity of findings and the limited data available, there is a need for specifically designed community-based and longitudinal research projects with well-defined control groups to study potential associations between BPD, fibromyalgia and CFS. Chart reviews of patients diagnosed with one or more of the disorders may also provide further information while limiting selection bias. In future studies, it would be helpful to investigate lifetime prevalence in addition to point prevalence as this may elucidate any temporal relationships between the disorders.

A growing body of research is shedding light on the connections between early childhood adversity, mental illness and chronic physical health problems.Reference Scott, Von Korff, Angermeyer, Beniet and Bruffaerts 29 Recent advances in neurosciences suggest that early life stressors induce persistent changes in neurocircuits which are implicated in the integration of emotional processing and regulation of arousal and vigilance.Reference Heim, Wagner, Maloney, Papanicolaou, Solomon and Jones 17 It is postulated that these changes result in increased reactivity to the environment, increased pain sensitivity, depression, anxiety and altered sleep patterns.Reference Heim, Wagner, Maloney, Papanicolaou, Solomon and Jones 17 It is not surprising, then, that all three disorders of interest are associated with early childhood adversity. It is possible, then, that the apparent patterns of comorbidity we encounter in clinical practice stem from common risk factors for all disorders of interest, rather than a specific relationship between any or all of the disorders.

Until more evidence is presented to either support or refute possible associations between the disorders of interest, the authors will continue to maintain an index of clinical suspicion for conditions such as fibromyalgia and CFS in patients with BPD as part of a thorough psychiatric assessment.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lexi Ewing, Research Assistant with the Department of Psychiatry at Queen's University, for her help.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.