Background

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there is a global shortage of 10.3 million healthcare professionals, expected to rise to 12.9 million by 2035.1 It is further estimated that there is a shortage of 2.8 million physicians worldwide,2 with low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) suffering the brunt of this burden.3 Psychiatry is no exception to the growing workforce shortage. Indeed, over the past 20 years, psychiatrists’ numbers have risen by only one-third compared with population numbers, which grew by 4.3 million, or 6.9%.Reference Sederer4 Clearly, a highly skilled workforce is essential to deliver high-quality patient care. This generates global competition for the scarce workforce resource.Reference Mathur5 The consequent global migration has sparked a broad international debate about sustainability, distributive justice and global societal accountabilities, not to mention the well-being of the migrant workers.Reference Aluttis, Bishaw and Frank6 Hitherto, the medical and allied healthcare workforce has been regulated within national boundaries. The post-COVID-19 surge in virtual working in health systems offers an opportunity for low-cost economies to contribute workforce to higher-paying economies without the damaging impact of the current brain drain. However, given the wide variation in technological development and support infrastructures among healthcare providers across the world, along with a huge variation in economic strength across nations, the opportunities of globalising digital healthcare are counterbalanced by the challenges (Table 1).Reference Dave, Abraham, Ramkisson, Matheiken, Pillai and Reza7 This editorial offers a potentially different view, providing a way for matching international demand with virtual workforce supply.

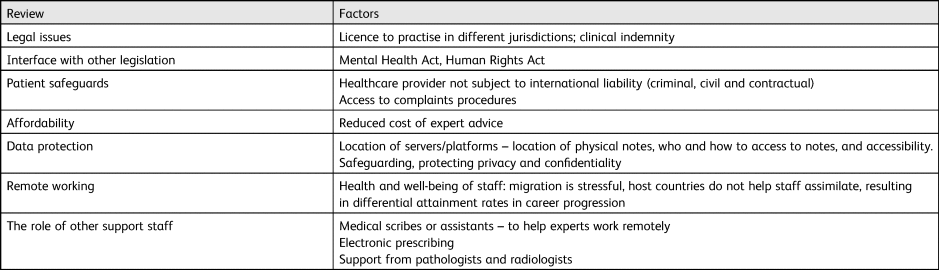

Table 1 Challenges and opportunities associated with a virtual international healthcare workforce

Digital solutions and healthcare leadership

Technology has played a big part in medical care for a very long time, especially in remote and rural communities. Bashshur et al define telemedicine as the establishment of medical care minus physical patient–doctor presence.Reference Bashshur, Shannon, Krupinski and Grigsby8 Weinstein et al also suggest the term telehealth, with an extended scope, encompassing telemedicine and including telenursing, telepharmacy, public health and health education.Reference Weinstein, Lopez, Joseph, Erps, Holcomb and Barker9 Digitalisation, globalisation and environmental issues, as they converge, will have a significant impact on organisations in the future related to how and where the workforce will work. Although an interconnected healthcare system offers new hope of bringing equitable and effective healthcare for all, there remains mistrust of technology, particularly in an intensely personal matter such as healthcare. However, digital solutions have often been adopted at a faster pace in emerging economies, for example in mobile payment technology. Whether similar paced innovations can occur in a highly regulated service such as healthcare remains a moot question. Facing off the twin challenge of workforce scarcity and designing and delivering sustainable health systems will require us to hold our ‘global nerve’ in adopting new technological solutions while keeping ‘up to date with the evolving compliance landscapes’.Reference Guo, Ashrafian, Ghafur, Fontana, Gardner and Prime10

Efficiency

Telemedicine definitions above were termed in 1969 and 1978 and so are not a new endeavour, and earlier applications of remote consultation have been utilised in primary care.Reference Liddy, Moroz, Mihan, Nawar and Keely11 Remote consultation allows patients to obtain a consultation and expert opinion in a timely manner from the comfort of their own homes. For clinicians, it offers flexibility in their working practice, while for health systems, reductions in missed appointments (‘did not attend’ patients) and efficiencies through reduced travel time for clinicians creates extra clinical capacity to offer a potential solution to excessive waiting times for specialist care. Waiting lists remain a serious concern in many countries, especially in the post-pandemic period.Reference Liddy, Moroz, Mihan, Nawar and Keely11

Effectiveness

Earlier reviews evaluating the use and impact of remote consultation in primary care showed wide-ranging effectiveness in terms of providing faster access to specialist advice, with short response times for some providers, and there was evidence of substantial avoidance of face-to-face referral visits among the participating specialists.Reference Liddy, Moroz, Mihan, Nawar and Keely11–15

In a recent systematic review of meta-analyses, Snoswell et al aimed to synthesise evidence associated with the clinical effectiveness of telehealth services.Reference Snoswell, Chelberg, De Guzman, Haydon, Thomas and Caffery16 The review found 38 meta-analyses, covering 10 medical disciplines: cardiovascular disease, dermatology, endocrinology, neurology, nephrology, obstetrics, ophthalmology, psychiatry and psychology, pulmonary and multidisciplinary care.Reference Snoswell, Chelberg, De Guzman, Haydon, Thomas and Caffery16 The results across all disciplines indicate that telehealth across a range of modalities is as effective, if not more effective, than usual care.Reference Snoswell, Chelberg, De Guzman, Haydon, Thomas and Caffery16 However, we agree with the authors of the review, who concluded that the existing data are very specific to each discipline, highlighting a need for more clinical effectiveness studies on telehealth across a broader range of clinical services and safety. Despite the assertion that telemedicine will not be the first choice in all contexts, these findings indicate that in appropriate situations, telehealth will not compromise the effectiveness of clinical care when compared with conventional forms of health service delivery.

Accessibility

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the acceptance of such technology for routine medical and psychiatric care has surged.Reference Yellowlees, Nakagawa, Pakyurek, Hanson, Elder and Kales17 ‘Digital poverty’, however, remains a noticeable determinant of health outcomes for patients who do not have smartphones or alternatives with good internet access.Reference Bauer, Glenn, Geddes, Gitlin, Grof and Kessing L18 In some jurisdictions, it seems increasingly likely that most rare diseases will be managed through a network of centres of expertise utilising remote consultation systems that become a vital component of the service offered.Reference Drop, Mure, Wood, El-Ghoneimi and Faisal Ahmed19 Clearly, telehealth is beneficial to patients in specific contexts, such as those living in rural areas or with impaired mobility, ensuring access to clinical expertise. Moreover, its advent ties in well with the general trend towards increasing self-management and greater patient empowerment.20 However, telehealth broadly and telepsychiatry more specifically, while as effective as usual care, may not be the choice of all individuals in every context.

Consequently, the pandemic has highlighted opportune prospects such as an ‘uberisation’ of healthcare workers matching demand and supply. This has been relatively well-established in radiology,21 where remote analysis of digital scans is becoming relatively commonplace. In psychiatry, the reliance hitherto on importing workforce usually from LMICs to high-income countries (HICs) may give way to a two-way or even reciprocal exchange of human resource, with high-recruiting countries providing some of their high-value resource to LMICs consistently rather than through programme grant-driven ad hoc arrangements of the old days. Remote assessments in psychiatry, including specialist neuropsychological tests, psychopharmacology advice and interpretation of neurophysiological tests, are well within the realms of possibility.

Sustainability

The WHO supports countries in building climate-resilient health systems and tracking national progress in protecting health from climate change.Reference Hileman22 Perhaps ‘flying doctors’ are not good for the environment? Renewable-energy powered, remotely working professionals might be better in some, if not all, cases. The direct damage cost to health due to the global crises of climate change is estimated to be between US$2–4 billion per year by 2030.Reference Hileman22

Leveraging artificial intelligence to improve health outcomes

Promising artificial intelligence (AI) options are available to help handle the vast volume of patient's health-linked data with reduced intervention from staff. AI systems are showing promise in aiding the identification of those at risk of self-harm or suicide and can help optimise treatment plans for individuals. The advent of AI-driven bots to triage patients for video consultationsReference Lovett23 opens the opportunity for remotely located staff to optimally match patients with workforce depending on identified need. AI bots are meant to relieve pressure on a scarce workforce. An equally important task is to match clinical need with appropriate expertise. Giordano et al's tantalising finding that it is possible to predict outcomes and personalise psychiatric treatment by using machine learning offers a vision of AI-assisted personalised care, especially given the advances in computation technology enabling deep learning of large data-sets. However, the substantial challenge of separating noise from signal makes clinical implementation a difficult and possibly distant proposition.Reference Giordano, Brennan, Mohamed, Rashidi, Modave and Tighe24 It is more likely that in the near future, AI and machine learning will assist clinicians in improving the efficacy of clinical decision support tools.

Cost-effectiveness

Remotely located workforces have led to improved cost-effectiveness in a range of service industries, such as banking and customer care. The healthcare industry has been a relatively late entrant to remote working, but the pandemic has accelerated the pace of this change. Remote healthcare offers a cost-effective solution to address the poverty of skilled clinical resource.Reference Ri, Daehan, Humaun Kabir, Mahmud and Kyung-Sup25 Certainly, studies have shown that loss in productivity is lower in remote clinics than in standard out-patient clinics.Reference Jacklin, Roberts, Wallace, Haines, Harrison and Barber26–Reference Nelson, Russell, Crossley, Bourke and McPhail30

Reports of provider experiences, quality of responses/feedback and impact on healthcare support and workloadReference Thijssing, Van Der Heijden, Melissant, Chavannes, Witkamp and Jaspers31 suggest that the provider experience is generally positive in these domains and point out that remote consultation has the potential to improve overall job satisfaction and retention in geographically remote communities and provide educational/continuing professional development.Reference Thijssing, Van Der Heijden, Melissant, Chavannes, Witkamp and Jaspers31,Reference Soriano Marcolino, Minelli Figueira, Pereira Afonso Dos Santos, Silva Cardoso, Luiz Ribeiro and Alkmim32

Global workforce, migration and healthcare

Migration of healthcare workers is not a new phenomenon. HICs have relied on workers trained abroad for decades. One sophisticated attempt to map and quantify healthcare workforce flows was conducted in 2007 by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which reviewed the in- and outflow of doctors and nurses in OECD countries based on the best available data.33 The study showed that over the past 25 years, the number and the percentage of foreign-trained nurses and doctors increased significantly in European countries.33 Thus far, India is the top source country and provided United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia with 69 000 Indian-trained physicians, it is estimated anywhere from 20% to 50% of Indian health-care workers seek employment overseas.Reference Walton-Roberts and Rajan34

There is a broad consensus in the scientific literature that health worker migration has negative effects on the native country and its people, while the receiving country and the migrating worker are chief beneficiaries.Reference Aluttis, Bishaw and Frank6 Saluja et al used the concept of the value of a statistical life and marginal mortality benefit provided by physicians to estimate the economic cost for LMICs of excess mortality associated with physician migration. They estimate that LMICs lose US$15.86 billion (95% CI US$3.4–38.2) annually due to physician migration to HICs. The greatest total costs were incurred by India, Nigeria, Pakistan and South Africa.Reference Saluja, Rudolfson, Massenburg, Meara, Shrime and Saurabh35 It is important to note that brain drain does not result in a one-time capital loss, but rather continues to affect LMICs each year that their physicians are out of the country.

More recently, evidence from an exploration of the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) healthcare staff in the UK has intensified the discussion by shining a light on the determinants of migration and immigration of international healthcare workers. The report has revealed the stresses experienced by international healthcare workers, such as poorer career progression, increased bullying and harassment, higher referral rates to regulators and, sadly, higher death rates related to COVID-19.36

Admittedly, migration may also be associated with beneficial effects, ranging from increased remittances to LMICs to transfer of technology and expertise. Whether migration strengthens or restricts transfer of technology and knowledge between countries remains debatable, but the pandemic has altered the scope of discussion linking technology and the migration process.

Modern electronic technologies have possibly transformed not simply the ‘spatial and temporal’ association between healthcare worker and patient,Reference Yellowlees, Richard Chan and Burke Parish37 but also increasingly the recruitment of healthcare workers themselves. Seventy-five per cent of patient–doctor consultations in the pandemic period took place remotely (defined as utilising telephone and video calls).Reference Richardson, Aissat, Williams and Fahy38 As medical tourism is set to become less possible between countries in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, participatory treatment and the accessibility of marketable technologies can provide patients with extra possibilities to view and track their health information and to connect with their providers. For some, medical care will be delivered in the palm of their hand, in the comfort of their own home. Recently, a healthcare provider in the UK advertised a ‘virtual’ consultant psychiatrist post with 100% remote working.39

Novel mechanism for levelling up global healthcare workforce equity

Could the underlying principle of remote consultations be the attractive alternative for health systems that are facing a crisis in recruitment of healthcare personnel and costs?

Expanding, improving and supporting the health workforce – collectively part of human resources for health – is of fundamental importance. Extending health coverage to more people and offering more services has proved challenging for many of the worst affected parts of the world.Reference Guilbert40 Codes of practice on ethical international recruitment – or similar policies – have been introduced at both national and international levels to protect the health systems of vulnerable countries.Reference Willetts and Martineau41 We contend that what the WHO's Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health PersonnelReference Guilbert40 has done is to expose the polarisation in the availability of health (including human) resources between HICs and LMICs. The WHO Code of Practice was an ambitious step in the evolution of what has become known as global health diplomacy, seeking to redress the imbalances among health workers around the world by raising important issues of human rights, including access to healthcare, equity and social justice.Reference Poz and Siyam42 The adoption of the Code in 2010 by all 193 member states of the WHO has put in place a new global health architecture.Reference Cooper, Kirton, Lisk and Besada43 This Code established and promoted voluntary principles and practices for the ethical international recruitment of health personnel and the strengthening of health systems.Reference Poz and Siyam42 It is a multilateral framework for tackling shortages in the global health workforce and addressing challenges associated with the international mobility of health workers. For these reasons, the role and relevance of the Code may require a revaluation in the areas shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Key factors requiring revaluation

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to the rapid, pervasive and local adoption of technology normalising remote consultations. Previously, digital technologies such as remote consultations were the preserve of geographically remote and rural communities, whereas AI and data mining were largely confined to urban scientific communities. Post-pandemic, technology not only offers access to local populations, including underprivileged areas, but crucially democratises access to healthcare technology across the world. The pandemic has had a significant impact on the global healthcare workforce and rates of burnout and stress have further depleted a workforce already short on numbers. Under such circumstances, migration from LMICs to HICs escalates – with consequences for all parties’ native countries, host countries, the migrating doctors and the patients. Migration of healthcare workers from LMICs leads to worsening healthcare outcomes in their native countries. However, although migrants might be lured by the holy grail of better prospects for them and their families, the reality is that some experience poorer career progression, less favourable pay and a professional risk of referral to regulators. Telemedicine could prove a novel mechanism for many LMIC doctors to ethically offer their services to HICs remotely. Alternatively, expertise from HICs that was expensive to import may now be available with fair compensation mechanisms and professional safeguards that may lead to widening access to the available healthcare capacity and lead to better matches between demand and supply. However, it is the future potential development that telemedicine could spread so widely that has raised questions surrounding the re-evaluation of regulation processes. Codes of practice on ethical recruitment have in the past been produced with the aim of ensuring ethical values, protecting vulnerable countries, workers and their patients. The policy initiatives developed in the past have, however, depended on the expansion of the medical workforce through the active recruitment of overseas qualified doctors.Reference Esmail44 Quality improvements in healthcare offered through advances in digital technology including telemedicine should be a fundamental right of the public to help access the best healthcare. The provision of high-quality care at a cost-effective price, while ensuring that there are regulations and policies in place to safeguard if things go wrong, should be a given when designing digital interventions. Good codes on guidance of such digital solutions will not only help globally migrant healthcare workers, but will also have the potential of transforming future health outcomes for millions of people around the world.

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Author contributions

S.D. and N.K. conceived the idea; N.K. prepared the first draft of the manuscript. N.K. and S.D. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

S.D. is Dean of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, London, UK.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.