Malawi is a landlocked country located in Southern Africa bordered by Zambia, Tanzania and Mozambique (Fig. 1). Its population was estimated at 17 563 749 in the 2018 population census and is expected to double by 2042.1 Malawi is one of the poorest countries in the world, with 51.5% of the population living below the poverty line and 20.1% living in extreme poverty.2 The economy is predominantly agriculture-based, with 80% of the population engaging in subsistence farming. Main exports are tobacco, sugar and tea.

Fig. 1 Map of Malawi with political and administrative divisions. Source: Malawi Demographic Health Survey 2015.

Prevalence of psychosis

There are no community prevalence studies of psychosis in Malawi. A few studies have been conducted in in-patient settings. The proportion of people with schizophrenia among all patients admitted to the Bwaila psychiatric unit in the central region of Malawi (1 January 2011 to 31 December 2011) was found to be 30%.Reference Barnett, Kusunzi, Magola, Borba, Udedi and Kulisewa3 In addition, 74.5% of all in-patients admitted to Zomba Mental Hospital in 2014 had psychosis of any cause (including organic and substance-induced psychoses).Reference Liwimbi4

Duration of untreated psychosis

The duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) in Malawi is high.Reference Chilale, Banda, Muyawa and Kaminga5,Reference Kaminga, Dai, Liu, Myaba, Banda and Wen6 Among people presenting to a mental health service in Northern Malawi, the median DUP was 28 months and the mean DUP 71 months.Reference Kaminga, Dai, Liu, Myaba, Banda and Wen6 Factors found to be associated with high DUP were poor insight, use of traditional healers, lower level of education, unemployment, younger age at onset of the first episode, diagnosis of schizophrenia, lower Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scores and greater severity of negative symptoms.Reference Chilale, Banda, Muyawa and Kaminga5–Reference Kaminga, Myaba, Dai, Liu, Chilale and Kubwalo7

Concepts of psychosis in Malawi

Culture and tradition play a significant role in the understanding of mental illness among community members in Malawi. There is no single unified local definition of psychosis, although the most common term used is ‘madness’ (misala). Within communities, people are identified as mentally ill by behaviours such as ‘roaming around’, ‘talking uncontrollably’ and ‘wandering naked’.Reference Wright and Maliwichi-Senganimalunje8 Many people attribute psychosis to illicit drug misuse and supernatural forces such as spiritual possession, witchcraft, curses and punishment for sins.Reference Crabb, Stewart, Kokota, Masson, Chabunya and Krishnadas9 As in other African countries, it is those conditions presenting with socially disruptive behaviours that tend to be considered mental illness.Reference Sorsdahl, Flisher, Wilson and Stein10 Therefore, the less obvious symptoms of severe mental illness are often missed, especially in rural areas.

Studies on the pathway to care for psychosis and other mental illness

A systematic review of the pathways to mental healthcare worldwide showed considerable variation across different countries.Reference Volpe, Mihai, Jordanova and Sartorius11 Compared with high-income contexts, fewer people in low- and middle-income countries seek professional assistance, and when they do, there are lengthy delays and inconsistent pathways to care.

A more recent systematic review showed that the first contact for the majority of people with psychosis in low-and middle-income countries was traditional health practitioners (THPs).Reference Lilford, Wickramaseckara Rajapakshe and Singh12 This was followed by mental health practitioners and primary care. Accessing THPs as initial contact was associated with a longer DUP.

In Malawi, traditional healers were found to be the first contact for 22.7% of psychiatric patients seen in one of the tertiary psychiatric institutions.Reference Kauye, Udedi and Mafuta13 For 23% of the patients, two different care providers were involved prior to referral to the psychiatric hospital. An MSc thesis looking at the pathways to care for people with first-episode psychotic disorders at Zomba Mental Hospital reported that 58% of the participants first sought medical advice from generalist clinicians/nurses, 28% from traditional healers, 8% from religious healers, 4% from Zomba Mental Hospital through the out-patient department and 2% from the police.Reference Nyirongo14

Method

This article is based on the Wellcome Trust Psychosis Flagship Report on the Landscape of Mental Health Services for Psychosis in Malawi, commissioned by the Wellcome Trust Innovations division. The full report has not yet been published online. The information was collected using a variety methods: literature review, including published studies and grey literature from Malawi (theses, reports, conference proceedings, etc.); identification of key stakeholders within Malawi (experts by experience, clinical services, research and training institutions, research studies and units, non-governmental organisations (NGOs)) and external partners and collaborators; and an expert working group comprising ten key individuals in mental health in Malawi.

These multiple methods enabled us to have a comprehensive, up-to-date baseline for the Psychosis Recovery Orientation in Malawi by Improving Services and Engagement (PROMISE) project (see Discussion below) and to assess the impact of service developments over the 10 years or so since the previous pathways-to-care studies were done in Malawi.

Results

Where do people with psychosis seek help?

Traditional healers

Traditional healers are frequently the first to be consulted in Malawi for the treatment of mental health problems. Up to 60% of caregivers of people with psychosis seek their first help from traditional healers.Reference Chilale, Silungwe, Gondwe and Masulani-Mwale15 The exact number of traditional healers currently in Malawi is not known. However, in 2002 there were about 45 000 traditional healers registered with the International Traditional Healers Association in Blantyre District alone.Reference Robison, Sclar and Skaer16 A study of 1566 traditional healers across five districts found that they saw a total of 44 109 patients per week.Reference Harries, Banerjee, Gausi, Nyirenda, Boeree and Kwanjana17

Christian healing ministries

Christian healing ministries (principally through Pentecostal and Apostolic churches) are also commonly consulted for psychosis in Malawi. It is usually a family member or other relative that takes the person to a religious leader. The assumption is that psychosis is due to spiritual forces, particularly demonic ones, which can best be dealt with by the church.

Conventional mental health services

Primary level

The first point of contact with the healthcare system for people with mental illness in Malawi is usually at the primary care level through health centresReference Kauye18 staffed by general clinicians and nurses. The challenge at this level is both the lack of mental health services and specialists and, where they do exist, the frequent deployment of mental health professionals to other duties, such as maternity services. There has been an effort by the Ministry of Health to integrate mental health into primary healthcare,19 in alignment with World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines.20 A new mental health policy was launched in April 2020.19 The policy seeks to further improve access to integrated high-quality mental health services. However, implementation of this has been a challenge.

There are several mental health capacity-building projects targeting different levels of health workers in Malawi. For example, the Scotland–Malawi Mental Health Education Project (SMMHEP) implemented a training and supervision package based on the WHO's Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) to improve healthcare workers’ competencies and people's access to mental healthcare in five districtsReference Ahrens, Kokota, Mafuta, Konyani, Chasweka and Mwale21 and published the Malawi Quick Guide to Mental Health in 2020 to provide practical guidance for busy primary care healthcare providers. In addition, SMMHEP also supports psychiatric teaching and training for student doctors and other healthcare professionals.Reference Baig, Beaglehole, Stewart, Boeing, Blackwood and Leuvennink22,Reference Lindsay and Byers23

Secondary level

At the secondary level, district hospitals usually have psychiatric clinical officers and psychiatric nurses working together in district mental health teams (DMHTs).Reference Ahrens, Kokota, Mafuta, Konyani, Chasweka and Mwale21 The clinical officers have a BSc in clinical medicine (mental health) and the psychiatric nurses have either a diploma or BSc in psychiatric nursing. The district hospitals mainly provide out-patient mental health services. A few district hospitals have 2 to 5 rooms where they admit severely ill patients with mental illnesses for observation before referring them to the tertiary level. Each DMHT is also responsible for scheduling monthly community outreach clinics to health centres in their districts.

Tertiary level

Malawi has three specialist psychiatric units that offer in-patient and specialist mental health services. These are Zomba Mental Hospital in the Southern Region and St John of God Hospitaller Services in the Northern Region (Mzuzu) and Central Region (Lilongwe).

Zomba Mental Hospital was built in 1953 by the colonial administration and remains the main Ministry of Health referral psychiatric hospital in the country. It is located in Zomba district. It has approximately 2000 admissions per year and 400 beds. It provides in-patient and out-patient services to adults and some limited out-patient services to children. The hospital also provides forensic services, rehabilitation services and occupational therapy.

St John of God Hospitaller Services is a Catholic mission-run psychiatric service located in Mzuzu in the north and Lilongwe in central Malawi (http://sjog.mw). It provides in-patient and out-patient services, community services, counselling and substance misuse rehabilitation programmes. The two in-patient units provide a total of 88 beds (39 in Mzuzu and 49 in Lilongwe) and have approximately 700 admissions per year.

Other routes to accessing mental health assessment and care

Other potential pathways to care include schools and colleges, workplaces, police, courts and prisons. There are, however, very few mental health services offered at these places. Moreover, there is little done to increase awareness of mental health problems and to encourage help-seeking.

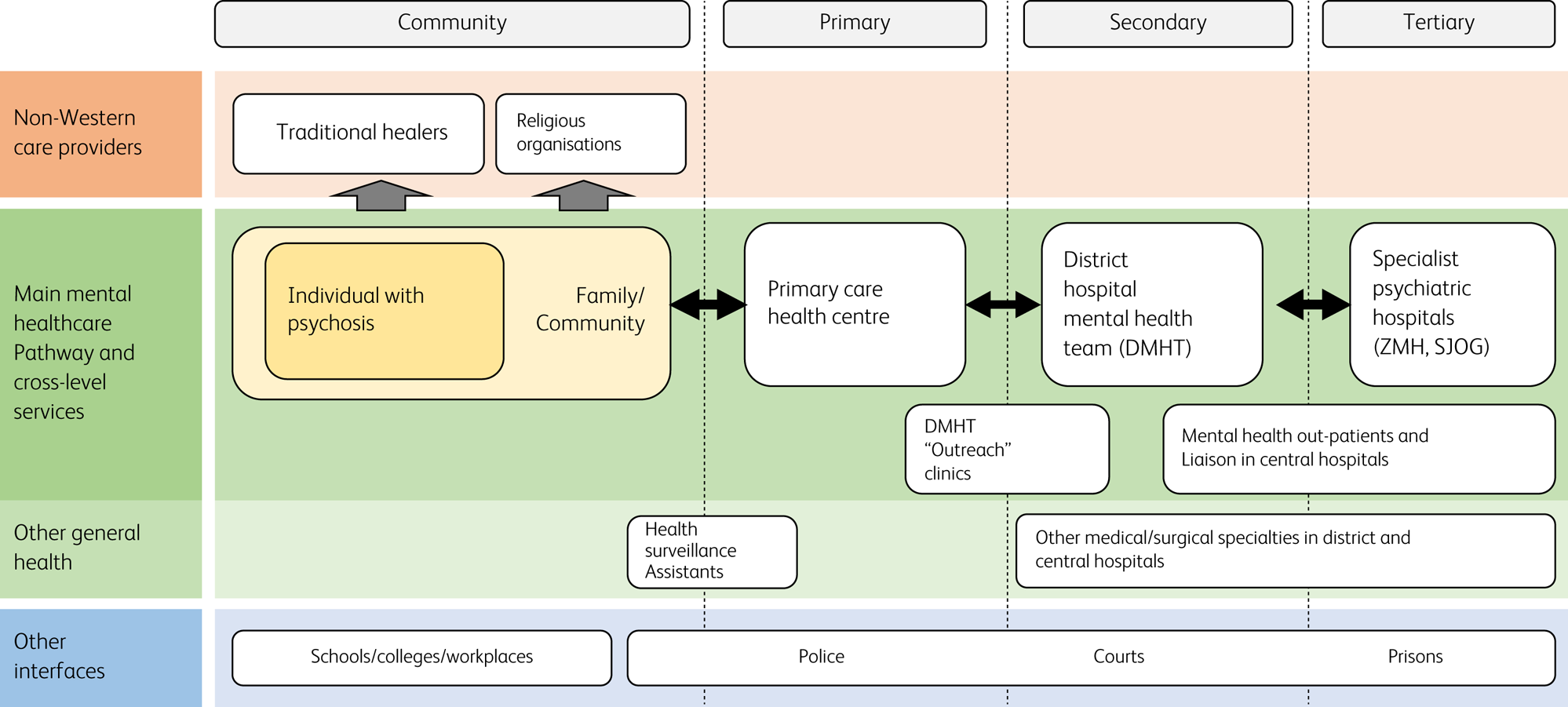

Fig. 2 summarises the care pathways for psychosis in Malawi.

Fig. 2 Care pathways for psychosis in Malawi. ZMH, Zomba Mental Hospital; SJOG, St John of God Hospitaller Services.

Staffing

In total, as of 2020, Malawi had only three psychiatrists, three clinical psychologists and one occupational therapist (information from interviews with key staff and records from key institutions, as there is no recently published data). There were seven social workers for mental health but none in the public sector. Table 1 below shows the numbers of different cadres of mental health workers in different facilities.

Table 1 Facilities and staffing for mental healthcare

Discussion

The findings of this paper are consistent with other studies globallyReference Volpe, Mihai, Jordanova and Sartorius11 and locally,Reference Kauye, Udedi and Mafuta13,Reference Nyirongo14 where variations of pathways for people with psychosis have been found. Traditional and religious systems continue to play a large role in the pathway to care for people with mental illnesses, including psychosis. These healing systems are important and integral to the core values and belief system of the Malawian culture and hence should not be ignored.

There is a strong (and growing) community of dedicated mental healthcare practitioners in Malawi, and many examples of good collaborative practice in the care of people with psychosis. There is also strong policy support for improving mental health services from the Ministry of Health.19 However, there are challenges at many levels in ensuring that consistent high-quality care for psychosis is available across the whole country. Broad issues include a lack of funding for mental healthcare, inadequate mental health facilities, a shortage of well-trained and equitably distributed health workers and the use of alternative healthcare systems. Challenges on the demand side include a lack of knowledge and awareness of mental health problems and services. There are also no early intervention services for psychosis.

Community-based health surveillance assistants (HSAs) are embedded in communities and could provide a resource for improving timely access to care. Wright et al demonstrated that, with a short training, HSAs can recognise and respond to the needs of people experiencing both common and severe mental health problems.Reference Wright and Chiwandira24 However, limitations to implementation include insufficient training, support and supervision; no clear referral pathways; and lack of funding. In addition, most HSAs hold similar, often stigmatising attitudes as their communities.Reference Wright and Maliwichi-Senganimalunje8

Community awareness-raising projects can assist in increasing people's knowledge about psychosis, encourage help-seeking and reduce stigma.Reference Stuart25 There are a few examples of awareness-raising projects in Malawi. For example, the Mental Health Users and Carers Association (MeHUCA) uses its established support groups to conduct different mental health awareness events.

PROMISE

It is against this background that the Wellcome Trust has funded Psychosis Recovery Orientation in Malawi by Improving Services and Engagement (PROMISE) – a longitudinal study that aims to build on existing services to develop sustainable psychosis detection systems and management pathways to promote recovery. PROMISE will work with people with lived experience of psychosis, all groups involved in the pathway to care (e.g. traditional healers, religious leaders, police, health workers) and other members of the wider community to develop systems for identifying people with psychosis and signposting to appropriate services. Studies have demonstrated that involving different stakeholders, including traditional healers, in the screening and management of people with psychosis provides positive outcomes.Reference Kilonzo and Simmons26,Reference Davies and Lund27

The PROMISE study officially started in 2022 and is divided into four work packages. Work package 1 involves engagement with stakeholders, including the participatory research method of ‘photovoice’, to investigate perspectives on psychosis qualitatively and quantitatively. Work package 2 will use theory of change and implementation science approaches to develop a manual for intervention and then recruit HSAs and train them in its use. Work package 3 will pilot the resulting psychosis detection and management system to screen for psychosis, support engagement in care and deliver community-based psychosocial interventions, in two districts of Malawi. Work package 4 will involve a 2-year evaluation of the psychosis detection and management system and the completion of a cost-effectiveness analysis.

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Author contributions

D.K. conceived the paper and wrote the first draft, organised with S.M.L. and R.C.S. All authors edited the drafts and approved the final version of the paper.

Funding

This study is an output of the Psychosis Recovery Orientation in Malawi by Improving Services and Engagement (PROMISE) study funded by Wellcome (223615/Z). R.C.S. also receives funding from the UK Medical Research Council/Global Challenges Research Fund grant to the University of Edinburgh (MR/S035818/1). The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the funding agencies.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.