The ward round is a key component of care provision in in-patient psychiatric settings.Reference Hopkins Rintala, Hanover, Alexander, Sanson-Fisher, Willems and Halstead1 However, studies have shown that the psychiatric ward round is not always an optimal environment for patients.Reference White and Karim2,Reference Cappleman, Bamford, Dixon and Thomas3 Although guidelines on how ward rounds should operate in eating disorder wards exist,Reference Clarke and Gardner4 they lack details on their content or how they are run. To our knowledge, there is no study examining how patients experience ward rounds in eating disorder settings.

Aims

The present study specifically focused on a single, 14-bed, adult eating disorders unit as part of a wider New Care Model (Provider Collaborative) initiative,Reference Viljoen and Ayton5 and sought to address the gap in the literature on ward rounds in eating disorder settings.

Historically, patients were not involved in ward rounds until 2014, when the ward round was renamed ‘clinical team meeting’ (CTM). In 2015, the service introduced the integrated cognitive–behavioural therapy for eating disorders (I-CBTE) model.Reference Ibrahim, Ryan, Viljoen, Tutisani, Gardner and Collins6 This model incorporates Dalle Grave's in-patient enhanced cognitive–behavioural therapy model (CBT-E) with a new framework for in-patients with eating disorders, where all health professionals and the patient sit at a weekly roundtable to discuss the treatment, a departure from the traditional top-down medical model.Reference Dalle Grave7 A previous audit identified issues relating to CTMs, including the meetings overrunning, patients lacking a sense of agency and the absence of psychologist input. The aims of this study wereReference Hopkins Rintala, Hanover, Alexander, Sanson-Fisher, Willems and Halstead1 to explore patients’ experiences and perception of the utility of CTMs; andReference White and Karim2 improve the current model of CTMs within the wider service improvement goals of embedding I-CBTE principles on the unit.

Method

A mixed-method approach was used. The study consisted of a mixture of in vivo CTM observations, focus groups and interviews. They were all held virtually because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Direct observations of the CTMs enabled comparison with previous literature on ward rounds and allowed a deeper understanding of the behaviours, meeting foci and attendee dynamics in a naturalistic context. Depending on patients’ preferences, focus groups and interviews were used to elicit in-depth insights into patients’ experiences and ideas for improving the CTMs. The focus groups/interviews were semi-structured, following a topic guide.

The Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public (GRIPP2) reporting checklistReference Staniszewska, Brett, Simera, Seers, Mockford and Goodlad8 was used to document patient involvement at all stages of the research cycle, as well as the outcomes of such involvement (Supplementary Table 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2023.14). The Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust's eating disorder patient forum and two former patients were involved in the conceptualisation, data analysis, co-production of service improvement initiatives and write-up, and one patient's (author L.R.) reflections on their involvement are included in Supplementary Appendix 1. ‘Patient’ was the preferred terminology, after discussing the study with the participants and a former patient in the ward who supported the study.

Ethics

The project was listed as a service evaluation based on the Health Research Authority decision tool, as it focused on quality improvement of a single unit and did not aim at generalising the findings.9 Hence, National Health Service (NHS) ethical approval was not needed. However, the authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human patients were approved by the Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust's Quality and Audit Department and registered on its quality improvement database. Informed consent was sought for audio recording of the CTMs and for patient participation in all stages of the study.

Participants

At the time of data collection, there were nine in-patients. All nine were invited but only six participated in the study. Five participated in two focus groups, and one participated in an interview. Of the six participants, five gave consent for the researcher to observe one of their CTMs. Patient participants were all female, five were voluntary patients and one was admitted under Section 3 of the Mental Health Act 1983.10 Ten staff participated in the CTMs: consultant psychiatrist (n = 1), psychiatry specialist trainee (n = 1), dietician (n = 1), core medical trainee (n = 1), specialty doctor (n = 1), medical student (n = 1), in-patient mental health advocate (n = 1) and nurses (n = 3).

Procedure and data analysis

CTM observations

The observation utilised a behavioural analysis approach.Reference Hopkins Rintala, Hanover, Alexander, Sanson-Fisher, Willems and Halstead1 Measures taken were minutes each staff member spoke; the length of the meetings and minutes spent on different areas of patient care, such as decision-making, formulation, risk and goal-setting. The meetings were audio-recorded. The field notes from the observations documented patients’ expressions and emotions, which helped to inform the analysis/coding of the qualitative data.

Focus groups and interview

The focus groups and interview were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and entered into NVivo version 12 (QSR International Pty Ltd, Burlington, USA; https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home). The duration of the interview was 35 min and the two focus groups took an hour each. The interviewer was a trainee clinical psychologist who was independent from the service, which helped maintain neutrality. Reflexive thematic analysisReference Braun and Clarke11 was chosen because of its flexibility, its focus on identifying patterns rather than having an idiographic approach, and its emphasis on uncovering latent meanings and reflexivity. Themes were subsequently refined with a former in-patient who experienced CTMs. Critical realist ontology was used, which recognised the viewpoints of different stakeholders and their experiences while locating it within the service context (including our knowledge of the unit philosophy and service development plans, as well as lived experience of being in the ward as an ex-patient).Reference Cassell, Cunliffe and Grandy12

From findings to service improvement initiatives

The findings were used to inform the service improvement initiatives, which were identified through discussing the findings with the I-CBTE multidisciplinary working group and the former patient. The first author (S.H.Y.) disseminated the findings in a nurse training session and patient community meeting, and they were subsequently implemented.

Results

CTM observations

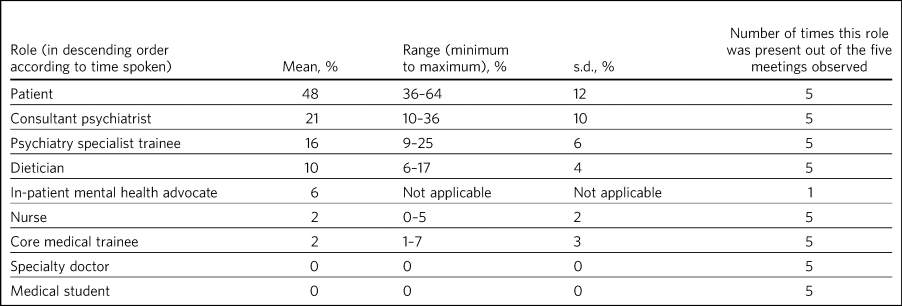

The mean duration of a CTM was 14.3 min (range: 7–24.3 min). Table 1 below shows the percentages of the time that each role spoke for in the CTM (N = 5). As shown in the table, the patient spoke the most in the meeting (48% of the time), followed by the consultant psychiatrist (21%) and the psychiatry specialist trainee (16%). The dietician spoke about 10% of the time. The in-patient mental health advocate attended one of the five meetings and spoke for 6% of the time. The core medical trainee and nurse spoke about 2% of the time, and the specialty doctor and medical student did not speak at all. It is worth noting that no psychologist or occupational therapist was present in the meetings observed.

Table 1 Time that each role spoke for in the clinical team meeting (N = 5)

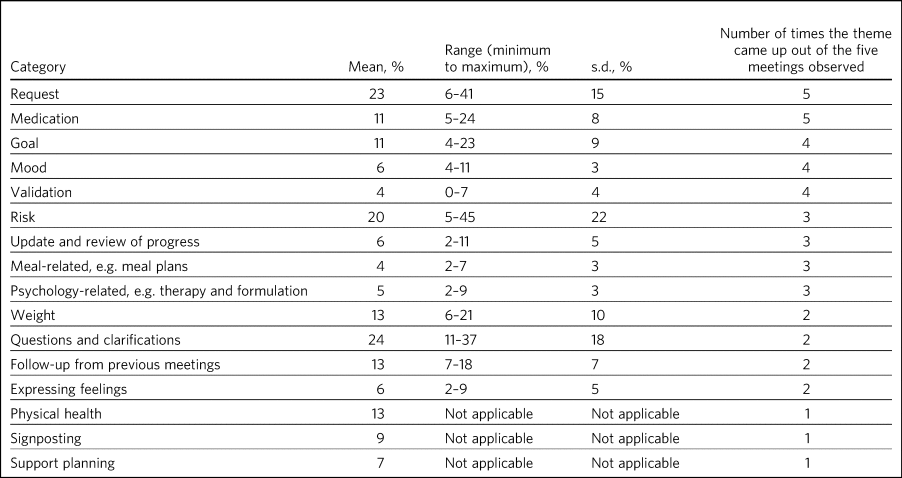

Table 2 shows the mean percentage of time and number of occurrences each coded category was mentioned in the meeting. A few categories were discussed more often than others, including requests (e.g. home leave, increasing break times – an average of 23% of the meeting) and medication (11% of the meeting). Risks such as self-harm and alcohol use (20%), and clarification/questions (24%) also took up considerable amounts of time in the meetings in which they were discussed, followed by physical health, weight and follow-up actions (13%). Psychology-related concerns such as the patient formulation were mentioned in three of the meetings and took up an average of 5% of the time.

Table 2 The amount of time each category was mentioned in the clinical team meeting

Thematic analysis of the interview and focus groups

Three themes were identified after an iterative process of theme development with a former patient.

Theme 1: the CTM is important but feels impersonal

The patients expressed a contrast between appreciating the importance of the CTM and experiencing a sense of impersonality in the meetings. A few factors contributed to the feeling of impersonality. CTMs felt too brief for any well-rounded discussion of a patient's treatment progress and goals. Although it is an important meeting, some participants felt that the people who made the key decisions were ‘strangers’. One patient said, ‘remembering the very first admission in the very first CTM I had, and I was taken to a room full of strangers and you have to tell them quite personal things, I found that absolutely terrifying’. In addition, the virtual format (owing to COVID-19) could exacerbate the impersonality. Remote working meant that patients may not have met the staff in person. There were mixed views about the new virtual format. Participants acknowledged that technical problems were barriers to a smooth meeting, and some felt overwhelmed by the many ‘strangers’ on the screen. Other participants, however, expressed feeling more comfortable speaking to attendees remotely as opposed to having many unfamiliar staff sitting in the same room: ‘I actually prefer if most of the people are remote, it makes it more comfortable to speak this time’.

Theme 2: a sense of palpable anxiety

Patients recognised the palpable anxiety on the ward on Mondays, when CTMs took place. This quote illustrates the level of unease:

‘There's a huge amount of anxiety surrounding CTMs into the point where I feel for the staff working on the ward on a Monday because everybody's really stressed. You know … there's a palpable sense of tension.’

A source of anxiety came from not knowing what to expect. One participant said, ‘You feel like this, this secret bag of things. You don't know how to access this’. Another participant expressed confusion, ‘I think clarity from the beginning would have lessen my anxiety … what it's for, how it works, what the process is, who is going to involve … What's their role? What's my role?’. The inherent power difference also contributed to the anxiety, as evident in the language used by both staff members and patients, such as the word ‘request’. This word carries the idea that patients and staff are not engaging in shared decision-making, and the power of approval lies within the clinical team. One participant said, ‘there are things that you request that get turned down … ’ Another quote echoes similar ideas, ‘ … I requested a 2-h ground leave on Saturday, is this approved? … Is that acceptable? We don't know what our boundaries are’.

Theme 3: staff and patients have differing views on the goals of CTMs

Although the staff team and some patients would like to embed an I-CBTE formulation into CTMs, explicitly discussing their psychological formulation might not be preferred by all patients because of the personal nature of the document. As one patient put it:

‘ … There are too many people, I feel very anxious because it [formulation] is a very personal document, I wouldn't want to share it with all the staff, one-to-one is fine but not in front of everybody, I wouldn't be comfortable.’

One participant noted the psychological dimension was missing in the CTM:

‘Like one of my goals is like, building up relationships and things, but there isn't any, much of the psychologist side of therapy side of the CTM, there's the dietician side and doctor side, the other stuff so we don't talk about the other goals?’

However, others felt therapy groups might be a better place to discuss the psychological aspects of treatment: ‘I think the groups help much more with goals much more than CTM … things like the goal setting groups and formulation groups are much more helpful in that respect’. There appeared to be different views around patient empowerment. Staff members wanted to move toward a culture of patients taking initiatives and being active in their CTMs in line with Dalle Grave's roundtable approach. Nevertheless, some patients wanted to hear from the expertise of staff and have staff proactively feeding back, as evident in this quote:

‘They ask us how we think we might be getting on, but they don't say how they think we're progressing, and I think that would be encouraging if they said to us, oh I think you are doing really well on AB and C but maybe you need to work on X, Y. We don't get any response. What they think.’

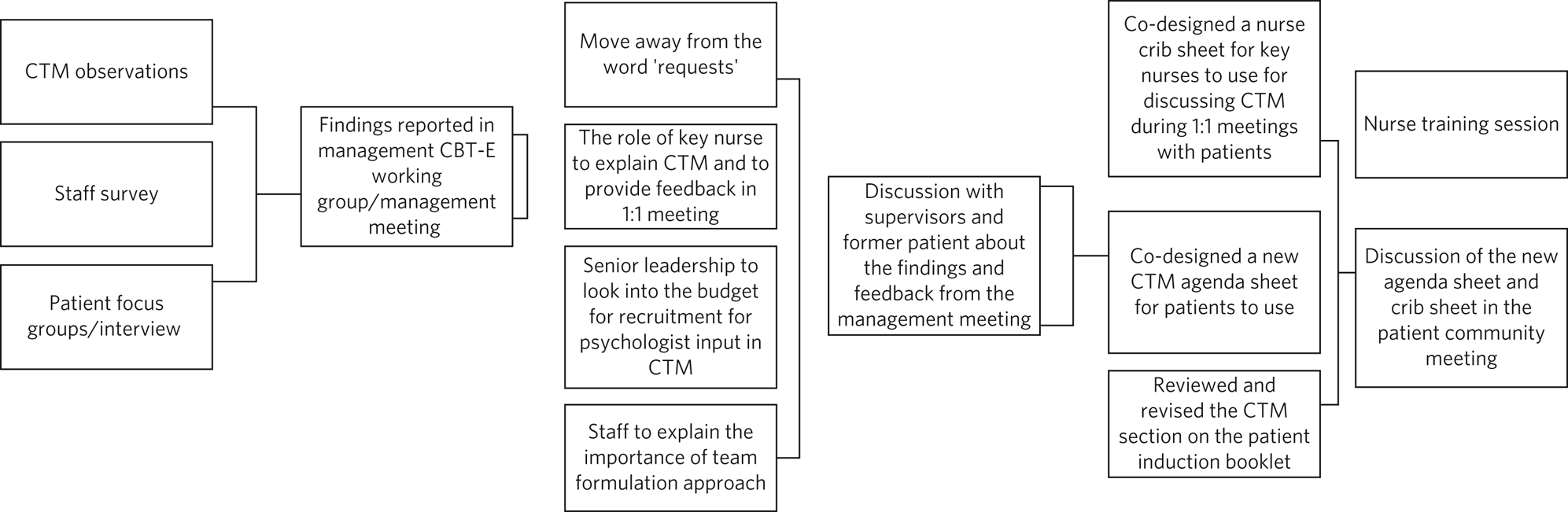

Service improvement initiatives

A diagram of the data collection, dissemination and improvement process so far is shown below (Fig. 1). Senior staff found the results helpful. They acknowledged that the meeting is short for everything to be covered and would like to have psychological input in CTMs but it had been difficult because of budget/staffing issues. The service decided to revise the patient induction booklet and created a new CTM agenda sheet (Supplementary Appendix 1). The former patient suggested making a guidance sheet for nurses to help patients prepare for CTMs. A nurse training session and patient meeting ensued, focusing on using the new documents. Eight nurses attended the training. They agreed with the idea of moving away from the language of ‘request’ and proactively giving positive feedback in relation to making progress on any goals based on the patient's unique formulation. For example, rather than ‘you are doing well’, the feedback could be more specific, pointing out how the patient managed to reduce an eating disorder maintaining factor (such as overcoming compensatory behaviours; addressing problems with body image, low self-esteem or perfectionism; or interpersonal difficulties), and how that helped them progress toward their goals. The idea was to be ‘formulation-driven’ while being sensitive to individual patient's wishes not to show the formulation in the CTM. Four patients attended the feedback meeting and found the new CTM agenda sheet more helpful than the old one. It was suggested that nurses distribute the forms 1 day before CTMs took place.

Fig. 1 Diagram showing the improvement process. CBT-E, cognitive–behavioural therapy model; CTM, clinical team meeting.

Discussion

Psychiatric ward rounds have been criticised for lacking patient participation and being stressful.Reference Lindberg, Persson, Hörberg and Ekebergh13 The service improvement project aimed to understand patient's experience of the CTM in an adult eating disorder ward and implement improvements based on the findings.

The observational data showed that, similar to early studies,Reference Hopkins Rintala, Hanover, Alexander, Sanson-Fisher, Willems and Halstead1 psychiatry colleagues spoke the most among all clinicians, and other professions (e.g. nursing, dietician etc.) spoke for <20% of the time. ‘Request’ was the most discussed category, and psychological aspects were spoken for only 5% of the time. Contrary to Hopkins Rintala et al,Reference Hopkins Rintala, Hanover, Alexander, Sanson-Fisher, Willems and Halstead1 patients in this study spoke the most in the CTM (roughly half the time), indicating that the service has come a long way since 2014, from patients not being invited to the meetings to having an active role and speaking the most in ward rounds. Reviewing and adapting the CTMs was part of a wider service transformation toward I-CBTE. This approach has shown significantly better patient outcomes compared with treatment-as-usual models in the UK.Reference Ibrahim, Ryan, Viljoen, Tutisani, Gardner and Collins6

The subsequent development of the CTM agenda form that better reflected patients’ needs and goals confirmed previous studies’ findings in relation to patients ‘needing a guide’Reference Lindberg, Persson, Hörberg and Ekebergh13 and preparing for the ward round in advance helped facilitate discussion and engagement.Reference Holzhüter, Schuster, Heres and Hamann14

The thematic analysis revealed differing views between staff team and patients, and there was still a sense of impersonality in the CTMs. The findings echoed with the wider literature on the power dynamics between clinicians and patients in eating disorder wards.Reference Zugai, Stein-Parbury and Roche15 The language of ‘request’ and ‘approve’ further reflected the power imbalance between staff and patients. As a result, there might not be standalone solutions to improving the CTM model without considering systemic factors such as staff–patient power hierarchy and ward culture. There seemed to be a lack of shared understanding in terms of patients’ role in the CTM: staff wanted the patients to take more initiative, whereas patients still reported a lack of agency. The power dynamic was possibly maintained by a multitude of factors: some patients might not feel comfortable or able to participate in the decision-making process, especially those who were extremely unwell or sectioned under the Mental Health Act. Furthermore, although the in-patient CBT-E model emphasised the importance of discussing one's formulation during meetings, some patients might not feel comfortable doing this because of the large number of professionals in the room. This was in contrast to the Dalle Grave model,Reference Dalle Grave7 where patients were voluntarily admitted and only a few key professionals attend the roundtable.

The pandemic contributed to the impersonal feelings, as some clinicians were working from home and patients might not have met the clinicians face to face. The situation has partially changed as post-pandemic, the CTMs are conducted in person once more. However, helpful lessons were learnt regarding the use of technology and how future hybrid CTMs could be conducted, e.g. with patients joining remotely when they need to isolate or cannot leave their rooms/beds. A hybrid approach also allows for the attendance of external professionals outside of formal review meetings (the Care Programme Approach).

In the context of the physical risks associated with eating disorders, there is a risk that services might assume a more ‘expert’ medical approach, resulting in them paying less attention to the underlying psychological processes.Reference Land16 Additionally, impaired decision-making is associated with people with eating disorders,Reference Guillaume, Gorwood, Jollant, Van den Eynde, Courtet and Richard-Devantoy17 and eating disorders are characterised by ambivalence toward recovery.Reference Geller, Zaitsoff and Srikameswaran18 Another maintaining factor is clinical perfectionism: patients worried that they were not responding to the agenda questions well enough. Moving toward shared decision-making CTMs requires a shift in attitudes from both staff and patients, steering away from the expert clinician and passive patient culture19 and toward the incorporation of psychological formulations to inform treatment.

The prevalance of anxiety is consistent with the survey results from White and Karim.Reference White and Karim2 Understandably, there is a baseline level of anxiety given the nature of CTMs, when important decisions are made. Additionally, the findings revealed that the decision makers were those who spent the least amount of time with the patients. CTMs could be seen as too brief for patients to deliberate, discuss and consider options, similar to findings from Lindberg et alReference Lindberg, Persson, Hörberg and Ekebergh13 in the older adult setting. Although staff members such as healthcare assistants and nurses wanted to be more involved, shift patterns and staff shortages meant that staff who spent the most time with the patients and knew them best were not always able to join the CTMs.

Limitations

The lack of psychological input affected the project. During the timespan of the project, three clinical psychologists left the service and there was an absence of a senior psychologist to support the project in-house. Consequently, it was difficult to provide psychological input during CTMs, and train and supervise new staff members. Furthermore, the lack of in-patient psychology leadership made it difficult to galvanise the team's engagement as the project's ownership was perceived to lie within the psychology leadership. Staff shortages meant that formulation groups were no longer running, hindering the development of psychologically informed CTMs, as not all patients had the opportunity to create a CBT-E formulation of their eating disorders.

Evaluating patients’ experiences after the implementation of changes was complicated by the turnover of patients and staff in the ward, meaning that if pre- and-post-measurements were taken, they would not come from the same participant group. Nevertheless, a strength of the service evaluation was its high patient buy-in (two-thirds of the in-patients took part in the focus groups/interview and two former patients supported the study).

Although generalisation is not claimed in this study, the findings resonate with other studies on patients’ and staff members’ experiences of psychiatric CTMs, and add to the existing literature by having valuable inputs from former patients and incorporating improvements based on the findings. Future improvements may wish to adopt methodological approaches, such as ethnography and conversation analysis, to study the social interactions on the ward. It was also noted that there might be a difference in experiences of voluntary versus sectioned patients. There was only one participant who was sectioned, and future research could examine the subgroups separately.

In conclusion, the co-production of a more psychologically informed process, including an amended admission handbook, CTM guidance sheet and training for nurses, helped to facilitate a more person-centred care. Services also need to recognise and address the power dynamics and specific psychological maintaining factors that affect the engagement and decision-making, to achieve shared decision-making between staff and patients. This also connects to sensitively attending to a patient's preference while also being aware of eating disorder maintaining factors (e.g. perfectionism and ambivalence to recovery) that influence the decision-making process.

About the authors

See Heng Yim is a clinical psychologist at Central and Northwest London NHS Foundation Trust. At the time when the study was conducted, she was a doctoral trainee in clinical psychology at University of Oxford, UK, and a trainee clinical psychologist at Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Roshan Jones is a clinical psychologist at Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Myra Cooper is a research director at the Oxford Institute of Clinical Psychology Training and Research, University of Oxford, UK, and a clinical psychologist at Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Lyn Roberts is a former in-patient at Cotswolds House, Adult Community Eating Disorder Service Oxford, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK. David Viljoen was a consultant clinical psychologist at Cotswold House, Adult Community Eating Disorder Service Oxford, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK, and is now a consultant clinical psychologist at Ellern Mede Group, UK.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2023.14

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author, S.H.Y., upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank all staff members and patients for their participation and support in this project.

Author contributions

S.H.Y. contributed to the conception, design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, and the writing of the work. R.J. contributed to the acquisition of the data, analysis, and revision and approval of the work. M.C. and D.V. contributed to the conception, design, and revision and approval of the work. L.R. contributed to the data interpretation, and revision and approval of the work.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.