LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading the article you will be able to:

• outline some of the barriers faced by professional footballers, and other elite athletes, that prevent them disclosing mental health difficulties

• describe the key concepts of the Power Threat Meaning Framework and be able to apply it as a non-stigmatising therapeutic model

• describe the important relationship between arousal and performance using the Yerkes–Dodson curve and use the curve as a template to discuss how to achieve optimal performance.

Surveys of the prevalence of psychiatric symptoms in professional footballers suggest their rates of psychological difficulties are similar to those of other professional sports participants (Gouttebarge Reference Gouttebarge, Kerkoffs and Mountjoy2021). One of the largest mental health surveys of footballers from a range of European countries (Finland, France, Norway, Spain, Sweden) showed rates of 25–43% for anxiety/depression, 19–33% for sleep disturbance, 11–18% for distress and 6–17% for alcohol misuse (Gouttebarge Reference Gouttebarge, Backx and Aoki2015). Research suggests that male U-21 players (under 21 years of age) show particularly high levels of depression (Junge Reference Junge and Feddermann-Dermont2016).

An article by Purcell and colleagues provides a helpful and comprehensive framework for meeting the mental health needs of elite athletes (Purcell Reference Purcell, Gwyther and Rice2019). It highlights the importance of: taking account of an athlete's social and ecological environments; the use of preventive strategies; early detection and management of difficulties; mental health literacy for athletes and support teams; and specialist mental health input in complex situations. The paper outlines a clinical pathway of interventions, from preventive strategies to specialist mental health management. An important omission in this framework, however, is the failure to suggest a model by which the clinical input is to be delivered (i.e. the model of treatment). We address this issue here, by proposing the use of the Power Threat Meaning Framework (PTMF) (Johnstone Reference Johnstone, Boyle and Cromby2018).

Introducing the PTMF

The PTMF (the key concepts of which are outlined in the next section) has been developed as an alternative to traditional models of therapy, which are based on psychiatric diagnoses. The PTMF is used as a way of helping people to create more hopeful narratives or stories about their lives and their difficulties. It avoids notions of blame, weakness, deficiencies and labels of being ‘mentally ill’. The PTMF also shows why people who do not have an obvious history of trauma or adversity can still struggle with poor mental health (Boyle Reference Boyle2022). It is suitable for people with and without mental health diagnoses, and focuses on both threats to people's self-esteem and the coping strategies they use to deal with such threats (Read Reference Read and Harper2022).

The PTMF has the potential to provide valuable insight and guidance for the management of mental stress in footballers. This is because it presents information in a non-pathologising manner, describing problems in terms of everyday events and responses. This is extremely important in relation to working with elite footballers because psychiatric labels (depression, generalised anxiety disorder, etc.) can be associated with stigmatisation. Therefore mental disorders are ‘often ignored by players and overlooked by coaches’ (Markser Reference Lucas2018: p. 138). Players also fear that admitting they have mental health difficulties will have a negative impact on their team selection, market value and possibly their standing among their fans. Since mental health problems are not openly discussed, many footballers and support staff at clubs are unable to recognise players’ mental health difficulties, and their problems may begin to manifest themselves as either low motivation, perceived as lethargy, or in the form of chronic physical ailments (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2021).

This denial of mental health difficulties has several consequences, one being that some players are treated by insufficiently qualified staff, including sports (performance) psychologists (Markser Reference Lucas2018). Nesti, a sports performance psychologist, concurs with this perspective and calls on performance psychologists to develop their clinical skills so they can deal adequately with players’ mental health problems in addition to their mental strengths (Nesti Reference Nesti2014, Reference Nesti, Ronkainen, Tod and Eubank2020). In a recent review paper we examined the types of therapy available to elite athletes, and to footballers in particular (this paper is available from the corresponding author on request). The review found an emerging evidence base for the use of rational emotive behaviour therapy (REBT) (Turner Reference Turner2014a, Reference Turner, Barker and Slater2014b), which is a form of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT). There was also evidence for the use of mindfulness (Carraca Reference Carraca, Serpa and Palmi2018, Reference Carraca, Serpa and Rosado2019) and compassion-focused approaches. Although such therapies are used widely in the general population, particularly the cognitive–behavioural approaches (e.g. Beckian CBT and REBT), they are not well established in football (Didymus Reference Didymus and Fletcher2017; Wilkins Reference Wilkins, Sweeney and Zaborski2020). For example, Wilkins and colleagues found that 8% of players in an elite academy had heard of CBT, and only 4% of players knew what CBT was (Wilkins Reference Wilkins, Sweeney and Zaborski2020).

Nesti, who has worked with several English premiership teams, believes that the problem with traditional modes of therapy is that they are overly rigid, jargonistic and fail to use language relevant to the needs of footballers. Nesti's preferred conceptual models are the existential approaches which, like the PTMF, are non-pathologising (Nesti Reference Nesti, Ronkainen, Tod and Eubank2020). A further advantage of the PTMF over the other therapies is that it explicitly emphasises the roles of coping strategies and strengths, making it a member of the family of ‘positive’ psychotherapies (Seligman Reference Seligman2002). This can be contrasted with CBT, which tends to focus on the re-evaluation of dysfunctional cognitions (beliefs and thoughts; Beck Reference Beck1975). It is worth noting, however, that PTMF's emphasis on the positive should not lull potential users of the approach into a false sense of safety. It is vital to remember that clinicians will be managing individuals with major mental health difficulties and they should be registered practitioners, receiving regular training and supervision.

The key concepts of the PTMF

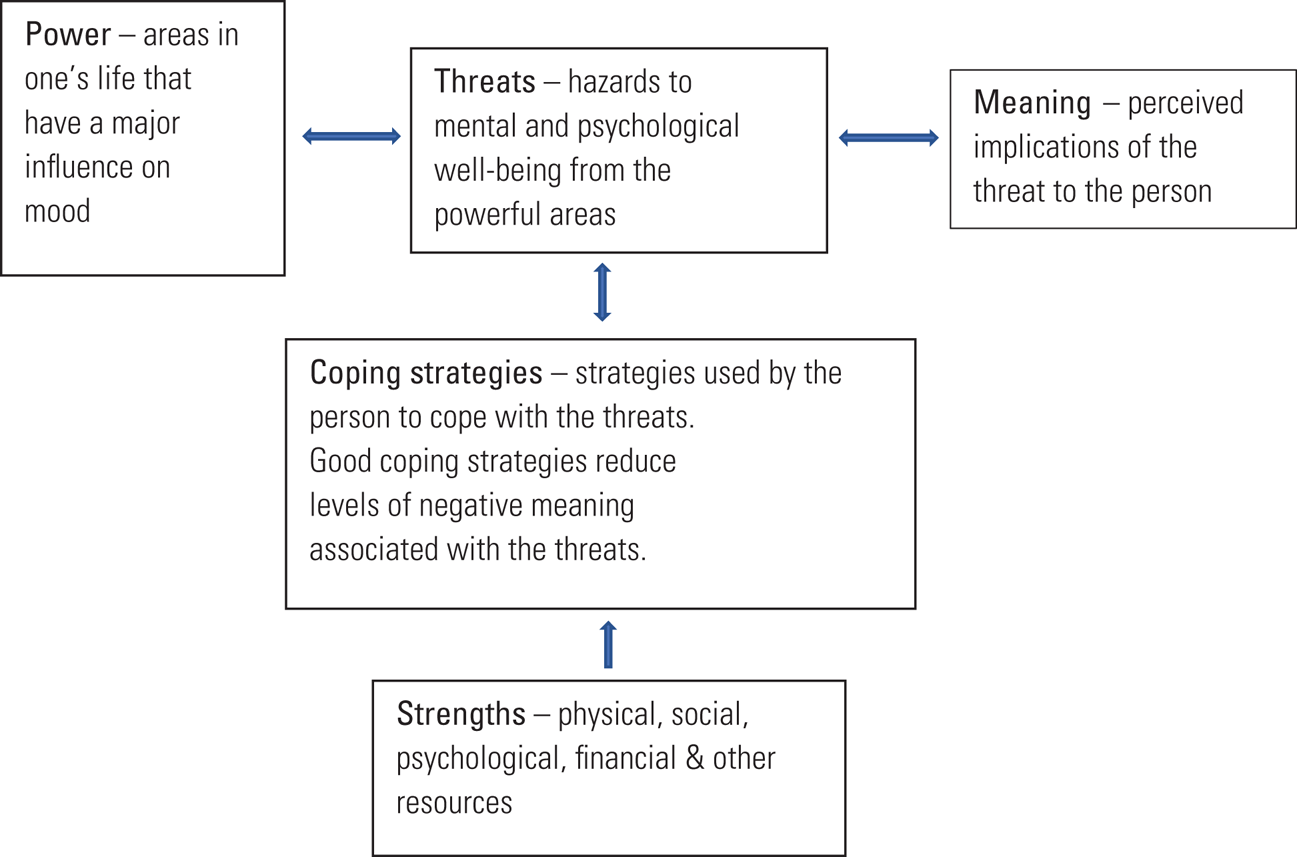

The proposed framework describes people's experiences of distress in terms of five main features: power, threat, meaning of threat, coping strategy and strengths:

• Power – A therapist using the PTMF approach with a footballer would typically ask the player what they regarded as being the powerful, or main, areas of influence in their lives (current and historical).

• Threat – Under this theme the player would be asked to state how these powerful areas may be threatening to their current status as a footballer, friend, partner, etc. These statements represent the potential threats to the player's mental health and well-being.

• Meaning – This theme relates to the meaning of the threat to the individual. A key question to ask is: ‘Do you feel that the threats are devasting and have traumatic consequences, or, in contrast, are they minor issues of little concern?’

• Coping strategies – The therapist also explores the coping strategies the player uses to help them deal with the threats. Later in therapy, the coping strategies would be examined to see how helpful and effective they are.

• Strengths – Finally, the player is asked to identify their strengths in the various areas of their lives, such as the physical, social, psychological, intellectual, interpersonal and financial. The strengths can be used to increase both self-esteem and perceptions of resilience.

Material from the five areas is portrayed diagrammatically in Fig. 1. It is worth noting that the degree of stress a person experiences is a product of ‘meaning × coping strategies’. Hence, even when a person assigns a great deal of negative meaning to a threat, if they feel they can cope ‘adequately’ then the stress levels will be manageable. If the stress is not manageable, it can cause problems, as illustrated in the next section.

FIG 1 The five areas of the Power Threat Meaning Framework (after Johnstone Reference Johnstone, Boyle and Cromby2018).

Mental skills versus stress: the normal curve

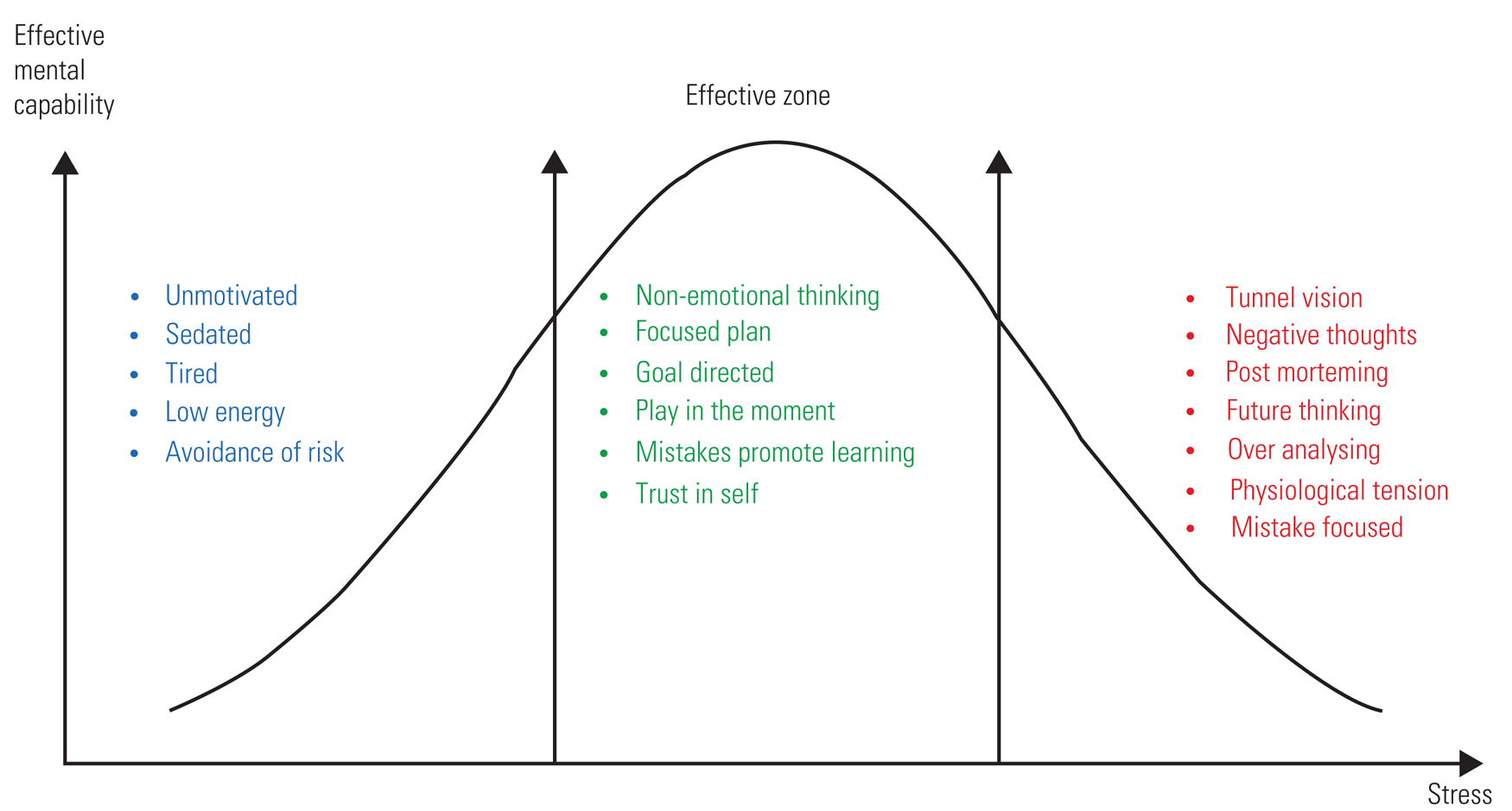

In this section we will examine the impact of stress on a footballer's performance using the Yerkes–Dodson law, which describes the relationship between stress and performance (Yerkes Reference Yerkes and Dodson1908). This relationship takes the form of a normal or bell curve that is symmetrical about the mean.

Figure 2 uses a Yerkes–Dodson curve to illustrate the impact of stress on footballers during a match. The horizontal axis indicates the degree of stress, from low to high. The potential causes of the stress are multiple (e.g. ‘fear of failure’, ‘criticism from managers’, ‘concerns about de-selection’, ‘worries about injury’, ‘anxieties external to football’). The vertical axis indicates the degree of mental functioning. The higher up the vertical scale the better the performance of the person's mental and thinking abilities. Hence, scoring high on this axis indicates the ‘brain’ is working well.

FIG 2 The normal curve illustrating the relationship between mental skills and stress and its impact on performance.

The diagram shows that at very low levels of stress, the player's arousal is too low for them to function well. In terms of their behaviour they will appear tired, unmotivated, disinterested, careless and showing low energy. In mental terms, their thinking will be slow, unfocused and unengaged. Their mood will be apathetic and unpredictable. They may not have the motivation to follow the coach's instructions.

In the middle section the player will be operating in the optimal zone, where the brain and mind will be working efficiently. At this stage the player will be playing at the height of their abilities, they will appear sharp, alert, moving well. They will make good decisions and be able to anticipate their opponents’ strategies. In terms of mental skills, we would see: good concentration, an ability to remain focused, effective mental control and coordination. They would be trusting in their own abilities and able to follow coaching instructions appropriately.

At the right-hand side of the diagram we see the negative effects of high levels of stress on a player's mental skills and performance. If we watched them, we might perceive them to be tense, overly emotional, hyper-aroused, rushed and chaotic. From a mental and brain perspective, they would be demonstrating overly emotional thinking, showing poor problem-solving skills and tunnel vision. They are likely to become self-critical, focusing excessively on mistakes and their implications for their future. As their thinking becomes more focused on themselves and their own performance, they will become poorer at carrying out roles assigned to them by the coach for the benefit of the wider team.

Using the PTMF

If a sports therapist were consulted for a player, their role would be to keep the player in the central zone of the stress–performance curve as much as possible. To do this the therapist needs to work on the player's pre-match and post-match preparations.

The therapist would initially help the player get into the ‘effective zone’ in the build-up to the match. This would involve enhancing the footballer's motivation and focus, addressing doubts and under-confidence, and dealing with issues (football/home life) likely to lead to overly emotional thinking.

The post-match period is also a critical time to provide support to the player. This is the period when the player is likely to be ‘post-morteming’ (going over the game in their mind) and receiving feedback from a range of sources. To be helpful for the player and to allow them to get into the effective zone in the next match, the feedback, particularly if critical, needs to be dealt with rationally and proportionately. In some football clubs, footballers are encouraged to try to delay the processing of the match until a day or so after their performance, to reduce the level of emotion attached to their thinking. Constructive feedback and criticism will need to be separated from the unwarranted destructive criticism.

It is important to note that the description of the Yerkes–Dodson curve has been simplified for the purposes of this article. However, the manner in which it has been represented here reflects the way the concept is often explained to professional footballers by coaches and medical teams. An animation demonstrating how the concept is presented to elite footballers is available from the corresponding author. For a more comprehensive overview of the Yerkes–Dodson curve, including a critique, see Corbett (Reference Corbett2015). Corbett's review shows that a person's particular position on the curve will be determined by a number of factors, including current task complexity, personality, current mental health, physiology and self-efficacy.

Case example: premier league footballer (JJ)

This fictitious case illustrates how the information from Fig. 2 and the PTMF can be used together to help a footballer (JJ), who has been struggling with his form in recent matches. It is evident that he is stressed and distracted, and when playing he appears tense and overly emotional, i.e. his presentation is best described as being in the right-hand side of the normal curve. Thus, Fig. 2 is helpful in showing some of the impact of JJ's distress on his performance and the direction he needs to travel to return to his regular form. In addition, the therapist could use the PTMF to help identify the underlying issues in JJ's life that are causing him to become stressed. In the development of the PTMF for JJ (Table 1), the therapist asked him the following questions:

• What's happened/happening to you? (powerful events affecting JJ)

• How does it affect you? (types of threat posed by the events)

• What sense do you make of it? (meaning of the threats for JJ)

• What do you do to cope with your difficulties? (coping strategies JJ uses to deal with the threats)

• What are your strengths? (the abilities and skills JJ acknowledges about himself).

TABLE 1 The Power Threat Meaning Framework for JJ

Table 1 highlights the powerful forces acting on JJ and his view of their implications. The meaning he attaches to some of the threats highlights that he is attempting to cope with many stressors. When one examines his range of coping strategies, they are not tackling the underlying causes of his difficulties. Apart from the excessive training, he is employing ‘sticking plaster’ remedies that are merely helping him get by (e.g. use of humour; inviting mates around). It is worth noting that the excessive training could also prove problematic, leading to overtraining syndrome, in which the player's body does not have time to recover, which has an impact on the endocrine system and leads to lethargy (Kreher Reference Kreher and Schwartz2012).

The therapist can use the information from both Fig. 2 and Table 1 to conceptualise the situation and produce an intervention plan. First, from examining Fig. 2 it is evident that JJ needs to move from the right-hand side of the graph to the central zone, in which case he would see an improvement in his focus, concentration, emotion regulation and performance. It is worth noting that many of the concerns described in the right-hand side of the graph are common for footballers, but only become dysfunctional when they lead to a decrease in performance. At such times the therapist would need to examine the meaning attached to the concerns and the coping strategies being deployed to deal with them. Matching the frequency and conviction of footballers’ thinking and coping to their performance is an area we intend to study over the next year.

In relation to treatment, it is always helpful to base clinical interventions on people's existing skills. JJ's skills as he describes them are outlined under the heading of ‘strengths’ in Table 1. Indeed, because he recognises himself to be bright, articulate and good with people, this information can be used to get him to address some of the threats. For example, he clearly needs to be helped to address the difficulty with the intimidating teammate and to regain confidence in his knee. He also requires some support regarding his marriage and assistance with his legal and financial problems.

The specific interventions a therapist might consider are: motivational interviewing to modulate JJ's levels of arousal and improve his problem-solving skills; elements of CBT for his worry and ruminations; sleep hygiene techniques to improve his sleep; the undertaking of a thorough assessment regarding potential alcohol and substance misuse. In addition, it is important to pay attention to the other issues highlighted in the PTMF because these threats also link directly to JJ's mood. Hence, all of the threats raised in Table 1 require some degree of focus, because if they remain unresolved they could continue to be sources of ongoing distress for JJ.

Caveat

The PTMF is an ‘umbrella framework’, providing an overarching structure, without dictating the process features that determine how the therapy is carried out. Consequently, to use the PTMF effectively therapists are required to have experience of other therapeutic approaches, using the change strategies within the other approaches to bring about clinical improvement. Although this might appear to be a weakness, it can also sometimes be a strength because it enables a therapist to use evidence-based techniques within a simpler, more accessible framework.

It is important to recognise that in certain circumstances, such as extreme distress, an athlete may require the use of a more established evidence-based therapy (e.g. REBT or interpersonal therapy), rather than proceeding with the PTMF.

Evaluation of the framework for elite athletes

Figure 2 is a helpful visual representation of the impact of stress on the performance of footballers. It is presented in terms that are easily understood, using sport-appropriate terminology. It is therefore a useful tool for people who may be neither ‘psychologically minded’, nor familiar with the language commonly used in therapy. The PTMF provides a framework for broaching conversations regarding an athlete's stress. The model has a high degree of face validity (Johnstone Reference Johnstone, Boyle and Cromby2018) and it uses non-stigmatising language and avoids lots of psychological jargon. These features reduce potential barriers for raising issues to do with stress and distress, facilitating the early identification and management of mental health difficulties. The user-friendly language also makes the approach more comprehensible to support staff, coaches and managers.

In addition to identifying difficulties and threats, the PTMF highlights people's coping strategies and strengths. This is helpful on several fronts. First, describing the coping strategies allows them to be assessed in terms of their degree of effectiveness. Beneficial strategies can be built on, while the ineffective ones can be tweaked or dropped altogether. Second, by asking the footballers to talk about their strengths and ‘ways of coping’, a conversation is initiated regarding their positive qualities. Helping a person to recognise their abilities is empowering, particularly when someone is feeling low. Such conversations also permit the therapist and athlete to explore together the many transferable skills that have enabled the footballer to be an athlete (determination, hard work, focus, desire to succeed) that they could also use to overcome their current difficulties.

As mentioned above, although the PTMF makes the topic of mental well-being more available and comprehensible, it is important to recognise that the process of conducting therapy within the framework requires the work of a skilled practitioner. The greater accessibility should not be a green light for either the unskilled or well-intentioned layperson to dabble and potentially increase players’ ill health. Wilkinson (Reference Wilkinson2021) recommends that football clubs offer a clinical space within the club where accredited therapists (counsellors, psychologists, psychiatrists) can work to appropriate ethical standards, offering confidential 1 h sessions. Nesti suggests that sports psychologists could potentially have an important role to play in this area, but notes that currently their training and focus is overly biased towards ‘performance’ rather than therapy (Nesti Reference Nesti, Ronkainen, Tod and Eubank2020). Sothern & O'Gorman's (Reference Sothern and O'Gorman2021) interviews with academy footballers in England found evidence in support of Nesti's position, finding that some psychologists had a bias towards performance rather than well-being. Sothern & O'Gorman used the following participant's quote to emphasise the point:

‘The psychologist says stay positive and don't let your feelings get hold of you, she says don't let your feelings take over your body if you feel sad you don't want to show it because you would focus on that in a game you could become conscious of people seeing it and it would affect your game.’

Wilkinson (Reference Wilkinson2021) notes that football clubs also need to promote commitment and trust in the therapist and counselling environment. The therapist should work closely with the medical team and coaches. Purcell and colleagues, speaking about athletes in general rather than just footballers, believe a ‘systems response’ is required to achieve improvements in elite athletes’ mental health. In their discussion about improving awareness and encouraging athletes to seek help, they make the following point:

‘These initiatives are unquestionably warranted; however, improving awareness and help-seeking behaviours are at best pointless, and at worst unsafe, if systems of care to respond to athlete's needs are not available. A whole of system approach needs to be developed simultaneously’ (Purcell Reference Purcell, Gwyther and Rice2019).

We concur with this perspective, believing a whole-system approach is required in football, and the approach should be supported by football's governing bodies. A good start was made with the signing of the Mentally Healthy Football Declaration by all the major leagues in the UK (Lucas Reference Markser, McDuff, Bär, Glick, Kamis and Stull2020). Yet, like many other campaigns, there still seems to be a reluctance to draw attention to problems experienced by players in the top clubs (Sothern Reference Sothern and O'Gorman2021). We therefore believe that future campaigns should be directed more specifically at the needs of elite footballers, whether they be in the first team or in their academies.

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Author contributions

I.J. undertook the conception and main writing of the article. The co-authors made significant contributions to the original draft, were involved in revising the article critically for important intellectual content and took part in all stages of redrafting.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 The Power Threat Meaning Framework is:

a a conceptual approach used to treat extreme aggression

b a non-stigmatising conceptual approach for understanding and managing stress and distress

c a framework used mainly in forensic services

d an approach for measuring relative degrees of threat

e a linguistic theory of communication.

2 The Power Threat Meaning Framework:

a requires the clinician to establish a diagnosis prior to treatment

b was developed as a non-stigmatising framework for treating mental health difficulties without the need for diagnoses

c was developed to treat people with aggressive personality difficulties

d was developed for people with treatment-resistant depression

e is a training framework for de-escalating aggressive situations.

3 The Yerkes–Dodson curve:

a is a statistical equation

b is a graph representing well-being and emotion

c is a straight line, showing the relationship between stress and performance

d is a normal-shaped curve, showing the relationship between stress and performance

e is a figure used in cognitive therapy to show the effect of well-being on emotion.

4 In terms of elite male footballers’ mental health:

a researchers have a good understanding of the prevalence of their difficulties

b researchers have found very high levels of mental health difficulties

c researchers have found high levels of psychosis and bipolar disorder

d researchers have shown that depressive disorders are very uncommon in players, although anxiety disorders are higher than in the general population

e researchers have struggled to obtain a good understanding of the prevalence of difficulties because of stigma associated with admitting to difficulties.

5 Motor performance observed in a sporting scenario:

a is always best at low levels of arousal

b is always best at high levels of stress and arousal

c is best when the athlete is sufficiently motivated, but not so aroused that their skills are impaired

d is not related to an athlete's level of arousal

e has not been adequately studied, and therefore adequate theories have not yet been developed.

MCQ answers

1 b 2 b 3 d 4 e 5 c

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.