LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article you will be able to:

• Develop a structured approach to the assessment of psychosis in Parkinson's disease

• Understand the evidence base for management of Parkinson's psychosis, in particular the role of clozapine

• Understand different models of structuring safe clozapine services in this setting.

People with Parkinson's disease present with a wide variety of non-motor symptoms in addition to the more widely recognised motor symptoms (Chaudhuri Reference Chaudhuri, Healy and Schapira2006). Many of the non-motor symptoms are psychiatric in nature and psychosis is one of the most difficult to manage. It has been estimated that, over a 12-year period, up to 60% of people with Parkinson's disease will develop hallucinations and delusions (Forsaa Reference Forsaa, Larsen and Wentzel-Larsen2010). Prevalence is higher in the later stages of the disease and this increases the risk of nursing home admission and has a significant impact on quality of life (Chaudhuri Reference Chaudhuri, Healy and Schapira2006).

Clozapine is licensed for use in psychosis during the course of Parkinson's disease, and is available in the UK as Clozaril®, Denzapine® and Zaponex®. It has a strong evidence base (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2017, 2018a), but there are a number of practical problems and obstacles that prevent it from being prescribed. Quetiapine is commonly used to treat Parkinson's psychosis, as it is much easier to prescribe than clozapine; however, the evidence base for its efficacy is unconvincing, further strengthening the argument that clozapine should be used where appropriate (Borek Reference Borek and Friedman2014).

In this article we will describe a practical approach to the assessment of Parkinson's psychosis based on our own experience in setting up clozapine services in England and prescribing clozapine for this patient group. We also outline the evidence base in relation to treatment options.

Assessment and management of Parkinson's psychosis

Psychotic symptoms in Parkinson's disease are common and not all will require intervention. One useful concept is to consider them occurring on a clinical spectrum – the so-called neuropsychiatric ‘slippery slope’ (Playfer Reference Playfer and Hindle2008). At the start of the slope would be symptoms such as reduced deep sleep and daytime sleepiness, moving through to vivid dreams, illusions and the feeling of presence. At the more severe end of the spectrum one finds complex visual hallucinations, delusions and organic confusional psychosis. The further along this spectrum the patient moves the more complex the psychotic symptoms become and the more likely the person is to experience distress and for their symptoms to have an effect on their day-to-day functioning. Hallucinations in Parkinson's disease are usually visual in nature but can occur in all other modalities.

It is important to remember that mild symptoms of psychosis may not need to be treated if they are well tolerated by the patient and carer. It is useful to have a structured approach to assessment and management and Boxes 1 and 2 show an approach adapted from Playfer (Reference Playfer and Hindle2008) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2017).

BOX 1 Structured assessment of Parkinson's psychosis

• At review appointments and following medication changes ask whether the patient is experiencing hallucinations (particularly visual) or delusions

• Offer an explanation to the carer to help them offer support to the patient, as they may be able to manage better with an awareness of what is happening

• Do not treat hallucinations and delusions if they are well tolerated by the patient and their family members and carers

• Exclude delirium or concurrent physical illness

• Consider environmental factors:

• Sensory overload from patterned furniture, carpet and curtains

• Inadequate lighting

• Get an optician's review

• Consider reducing medication for motor symptoms: do this in a cautious and stepwise manner

BOX 2 Pharmacological considerations in the management of Parkinson's psychosis

• First, consider reducing the last drug added

• It is helpful to consider reducing anti-Parkinsonian medication in the following order:

-

anticholinergics; other medications with high anticholinergic burden (e.g. tricyclic antidepressants); monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors; amantadine; dopamine agonists; catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitors; levodopa (L-dopa) (Playfer Reference Playfer and Hindle2008)

-

• Anticholinergics and dopamine agonists seem to be associated with a higher risk of inducing psychosis than levodopa or catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitors (Ismail Reference Ismail and Richard2004; Stowe Reference Stowe, Ives, Clarke and van Hilten2008)

• Consider quetiapine to treat hallucinations and delusions if there is no cognitive impairment

• If quetiapine is not effective, offer clozapine

• Be aware that lower doses of quetiapine and clozapine are needed for people with Parkinson's disease than for adults with other indications

• Do not offer olanzapine to treat hallucinations and delusions

• Recognise that other antipsychotic medicines (such as phenothiazines and butyrophenones) can worsen the motor features of Parkinson's disease

• No specific mention of aripiprazole is made in the NICE treatment guidelines, although in our clinical experience it is often offered if patients have not responded to quetiapine and clozapine is not available

• Rivastigmine or an alternative acetylcholinesterase inhibitor may be useful in improving behavioural symptoms in Parkinson's disease dementia but there is a lack of evidence to support its efficacy in treating predominantly psychotic symptoms of Parkinson's disease

• Memantine is not specifically mentioned in the NICE treatment guidelines for managing psychotic symptoms, although it may be considered in clinical practice, particularly in patients with cognitive impairment

• Pimavanserin is a selective 5-HT2A receptor inverse agonist available in the USA for Parkinson's psychosis, but it is not licensed in the UK and is not recommended by NICE

• For guidance on managing hallucinations and delusions in people with Parkinson's dementia, the NICE Parkinson's disease guideline NG71 (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2017) refers clinicians to the section on managing non-cognitive symptoms in its dementia guideline NG97 (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2018b). This advises prescribing antipsychotics only if the risks and level of patient distress warrant it and recommends a risk–benefit approach to prescribing. However, the guideline does not give any specific advice relating to Parkinson's psychosis. It may therefore be appropriate to consider an approach similar to that already outlined above for patients with psychosis in the context of cognitive impairment related to Parkinson's disease

In clinical practice patients with complex psychosis sometimes quickly exhaust treatment options. They may show a partial response to treatment with quetiapine but remain symptomatic and distressed by their symptoms.

The evidence base for clozapine use in Parkinson's psychosis

Clozapine is an antipsychotic medication mainly used for treatment-resistant schizophrenia; however, it is also licensed for psychotic disorders occurring during the course of Parkinson's disease, in cases where standard treatment has failed. A summary of the UK licenses for clozapine is shown in Box 3.

BOX 3 Summary of product characteristics (SmPC) for clozapine

The following points are taken from the UK official recommendations for Denzapine, Clozaril and Zaponex, the only clozapine formulations licensed in the UK

• Starting dose must not exceed 12.5 mg/day, administered in the evening

• Dose increments should be of 12.5 mg, at a maximum of twice a week up to maximum dose of 50 mg, a dose that should not be reached until the end of the second week

• The total daily amount should preferably be given as a single dose in the evening

• Only use >50 mg/day in exceptional cases and never >100 mg/day

• Dose increases should be limited or deferred if orthostatic hypotension, excessive sedation or confusion occur

• Blood pressure should be monitored during the first weeks of treatment (the licences do not specify how often this should be done)

• When there has been complete remission of psychotic symptoms for at least 2 weeks, anti-Parkinsonian medication can be increased if indicated. If there is recurrence of psychotic symptoms, clozapine dosage may be increased by increments of 12.5 mg/week up to a maximum of 100 mg/day taken in one or two divided doses

• Ending therapy: a gradual reduction in dose by steps of 12.5 mg over a period of at least 1 week (preferably 2 weeks) is recommended. Treatment must be ended immediately in the event of neutropenia or agranulocytosis, with careful psychiatric monitoring owing to the risk of recurrence of symptoms

The Parkinson Study Group carried out a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of low doses of clozapine (6.25–50 mg clozapine per day, with a mean daily dose of 24.7 mg) in people with medication-induced psychosis in Parkinson's disease (Friedman Reference Friedman1999). A total of 60 patients were included in the study, 30 in each arm. Three patients withdrew from each group. In the placebo arm, two withdrew owing to the worsening of their psychiatric condition and one was admitted to hospital for pneumonia. In the clozapine treatment group, one participant withdrew from the trial owing to leukopaenia, one because of myocardial infarction and the third because of sedation.

The clozapine treatment group showed significant improvement in their psychotic symptoms on a number of measures. Clozapine treatment improved tremor and had no deleterious effect on the severity of Parkinsonism. The authors concluded that clozapine at daily doses of 50 mg or less is safe in this patient group and significantly improves medication-induced psychosis in Parkinson's disease without worsening Parkinsonism (Friedman Reference Friedman1999).

The use of clozapine in Parkinson's psychosis is supported by a NICE quality standard, which states that ‘Services for adults with Parkinson's disease [should] provide access to clozapine and patient monitoring for treating hallucinations and delusions’ (NICE 2018a, p. 4). It recognises that anti-Parkinsonian medication can cause hallucinations and delusions which, if not controlled adequately, they can lead to admission to care homes. It also recognises that specialist Parkinson's disease services may not be able to provide a clozapine service directly and should agree with other local services how access will be provided and ensure that specific needs of people with Parkinson's disease (such as the need for a lower dose) are understood and met. Unfortunately, however, there is very limited national provision of clozapine services suitable for patients with Parkinson's disease and this NICE quality standard offers no care pathway or guidance on how to implement it.

Seppi et al (Reference Seppi, Chaudhuri K and Coelho2019) conclude that clozapine is efficacious in the treatment of psychosis in Parkinson's disease, that it carries acceptable risk with specialised monitoring and that it is clinically useful. They report that quetiapine has insufficient evidence but that it carries acceptable risk without specialised monitoring and is possibly useful. No other antipsychotics are deemed efficacious or safe in Parkinson's disease because of the associated risk of extra-pyramidal side-effects.

Pimavanserin is not currently licensed in the UK and has not be evaluated by NICE.

Barriers to the prescribing of clozapine in this patient group

In the UK, patients prescribed clozapine require a named prescriber registered with the clozapine patient monitoring service and supply is only via registered pharmacies with a nominated pharmacist. Clozapine patient monitoring services are mandatory in accordance with national official recommendations to manage the risk of agranulocytosis through centralised monitoring of leucocyte and neutrophil counts. Blood monitoring reduces the risk of mortality from agranulocytosis to 1 in 10 000.

At the outset, weekly blood tests are required for at least the first 18 weeks, reducing to fortnightly for the rest of the first year and then 4-weekly thereafter, tailored to the individual patient's profile. Monitoring continues throughout treatment and for 4 weeks after discontinuation.

Clozapine can cause tachycardia and postural hypotension, and therefore physical observation monitoring is needed at initiation and on dose increases. The licences do not prescribe the frequency of this. Other adverse effects include hypersalivation and constipation, both of which are already common in Parkinson's disease. Traditionally, the need for monitoring has limited the initiation of clozapine to in-patient admissions.

People with Parkinson's disease who experience psychosis may not be seen in psychiatric services unless they are in crisis, and even those who are seen are unlikely to have access to clozapine initiation unless they are admitted to an acute psychiatric ward, which tends to occur only if there is significant risk or severity of symptoms. Owing to the reduction in in-patient psychiatric beds and the move towards community treatment the possibility of elective admission for commencement of clozapine is slight.

The situation is further complicated by Parkinson's services being located within National Health Service (NHS) acute hospital trusts and most of the expertise and infrastructure for commencing clozapine lying within mental health trusts. Additionally, there are practical considerations to facilitate continuity of dispensing and supply. There are also risks inherent in people with Parkinson's disease being admitted to hospital.

The majority of clozapine use is in younger people with treatment-resistant psychosis, who often require high doses and fairly rapid dose titration. People with Parkinson's psychosis, on the other hand, use much lower doses of clozapine and need very little dose titration.

It is our experience that currently clozapine is often only initiated in this patient group when they are admitted in crisis to a psychiatric hospital.

As the next section shows, it seems that each service that could potentially offer clozapine for a specific patient lacks key infrastructure or expertise to be able to make the leap to treatment initiation.

Who could offer clozapine to people with Parkinson's psychosis?

A number of NHS services could provide clozapine treatment for Parkinson's psychosis, and here we list the pros and cons in each case and outline other barriers to service development.

Movement disorder services

Pros:

• Expertise in managing Parkinson's disease and anti-Parkinsonian medication

• Comfortable with managing comorbidities

• Used to making alterations to anti-Parkinsonian medication

• Knowledge of the individual patient, as they tend to follow up patients for the lifetime of their disease

• Can offer ongoing support for each patient.

Cons:

• Little knowledge or experience of prescribing clozapine.

Adult mental health services

Pros:

• Expertise in managing psychosis and prescribing clozapine, but in higher doses in the context of treatment-resistant schizophrenia

• Have the infrastructure for the dispensing of clozapine and the related monitoring requirements.

Cons:

• May only have access to clozapine initiation in hospital settings, depending on the configuration of services

• Less expertise in managing Parkinson's disease and other comorbidities.

Older adult mental health services

Pros:

• Expertise in diagnosis and management of dementia

• May be more comfortable with the management of Parkinson's disease than adult mental health services

• Offer routine community follow-up by community mental health teams, including community psychiatric nurses

• Have the infrastructure for the dispensing of clozapine and the related monitoring requirements.

Cons:

• Have expertise in managing psychosis but may not have as much experience in prescribing clozapine in their older population

• May only have access to clozapine initiation in hospital settings, depending on configuration of services.

Some other barriers to the development of clozapine services

• The heterogeneity of Parkinson's disease services and differing levels of input from mental health professionals mean that a ‘one size fits all’ approach will not work.

• There is no blueprint for the development of services that other services can easily adopt.

• It is not possible to take protocols for the use of clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia and translate them directly to services for Parkinson's psychosis.

• Clinicians’ lack of experience of prescribing clozapine in Parkinson's psychosis leads to uncertainty and anxiety.

• Disjointed care occurs between physical and mental health trusts, which often have different electronic patient record systems.

What is the national picture of clozapine provision for Parkinson's psychosis currently?

Unfortunately, it is unknown how much of the UK is currently able to access timely and appropriate initiation of clozapine for people with Parkinson's psychosis.

Until now there has been no sharing of good practice or established care pathways or policies.

We will now outline three clozapine services for patients with Parkinson's psychosis and share some reflections.

Clozapine initiation and titration in the Movement Disorder Service in Teesside – Dr Neil Archibald

Clozapine has been in routine use in the Parkinson's Advanced Symptoms Unit (PASU) for the past 5 years. The unit, based in Redcar Primary Care Hospital, is a rapid-access multidisciplinary service for people with Parkinson's disease who are at high risk of emergency admission owing to the severity of their symptoms. Many of these individuals will have undiagnosed dementia and/or distressing psychosis.

In addition to a neurologist, a Parkinson's nurse specialist, an occupational therapist a physiotherapist and a therapy assistant, the PASU team also includes a pharmacist and a community psychiatric nurse (CPN) from the local mental health trust. Part of the motivation for the PASU service was to proactively diagnose Parkinson's disease dementia, where psychotic symptoms are common, improve access to mental health interventions for our patients and find a way to safely offer clozapine to those who need it.

The initial phases of set-up were difficult. The major barriers were the inability to access clozapine through our acute trust's pharmacy, getting approval from the mental health trust to utilise their network of clozapine clinics for dispensing and monitoring, and navigating the shared ownership and decision-making required between our team and mental health teams across a geographically diverse area. This again reflects the description given earlier in this article that the expertise for prescribing clozapine is found across different services.

The current service model has the neurologist, supplied with an honorary contract with the local mental health trust, as the named clozapine prescriber, supported by the CPN. Once a patient and caregiver have been appropriately counselled on the risks and benefits, and are aware of the monitoring requirements, a provisional start date is decided, in conjunction with the local clozapine clinic for the patient's area. We liaise with local mental health teams as well, although the overall responsibility for prescribing comes from the PASU team. Registration with the Clozaril Patient Monitoring Service (CPMS) is done, with recent electrocardiogram (ECG) and full blood count (FBC) results required for this step. Patients typically attend the clozapine clinic for an orientation and their first ‘point of care’ FBC. They pick up their 7-day clozapine prescription and are booked back in for review the following week.

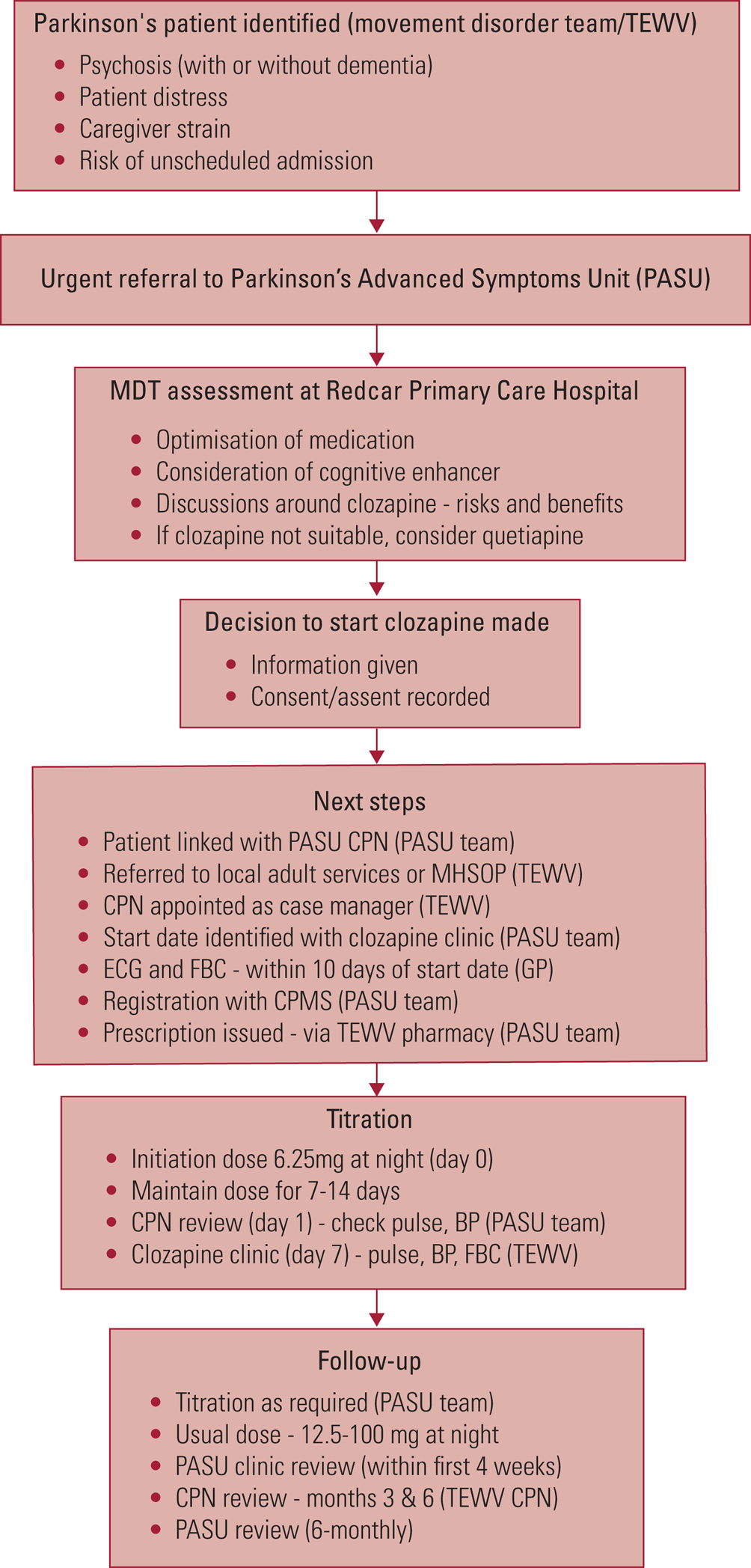

Figure 1 gives some idea of the process and which teams are involved in the various steps. Patients are reviewed the morning after the first dose, to check blood pressure and assess for any adverse side-effects. Further reviews are carried out at the clozapine clinic, as well as by local CPNs and, of course, the PASU team as well (both in clinic and at home).

FIG 1 Clozapine initiation and titration in the Movement Disorder Service in Teesside, UK. TEWV, Tees, Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Foundation Trust; PASU, Parkinson's Advanced Symptoms Unit; MDT, multidisciplinary team; CPN, community psychiatric nurse; MHSOP, mental health services for older people; ECG, electrocardiogram; FBC, full blood count; GP, general practitioner; CPMS, Clozaril Patient Monitoring Service; BP, blood pressure.

Originally, when we first started, we admitted patients to a mental health ward for clozapine initiation. We were worried about adverse events in a population at risk of complications. We found that this led to delays in treatment and prolonged in-patient stays. These were difficult for patients and their families and, of course, costly. As we grew more familiar with the systems, and the medication, we found that out-patient initiation reduced delays in treatment, and was feasible and safe. It is now possible to commence a patient on clozapine within 14 days of our initial assessment. Our light-touch approach results in considerable cost savings compared with a crisis in-patient admission.

There was understandable concern from the local mental health trust regarding the numbers of patients we would potentially require their help with. Thankfully, these concerns were unfounded. Overall, we have treated around 25 patients in the 5 years since the service opened, and these have been spread across a number of different mental health teams in our region.

We have had no cases of agranulocytosis and only a small number of ‘amber’ blood results. One patient stopped clozapine owing to problems with balance and drowsiness, but these are common to other medications we use, and also seen in advanced Parkinson's. Two other patients stopped the medication due to lack of efficacy.

Patient and caregiver feedback has been excellent and, overall, we have seen significant improvements in psychosis and a number of other symptoms as well. Anecdotally, our experience is that, even with very low doses, anxiety and nocturnal sleep improve early on. This gives some respite for caregivers in particular, who experience significant stress and sleep deprivation. We titrate the dose very slowly, and rarely need to exceed 50 mg, given at night. We typically expect to see a reduction in psychosis within 4–6 weeks, and counsel patients accordingly.

Royal Devon and Exeter Clozapine Service – Dr Sarah Jackson

Clozapine was being prescribed for patients with medication-induced psychosis in Parkinson's disease at the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital over a decade ago, and it was clear that it could be of huge benefit for patients, often making the difference between being admitted to a nursing home or being able to say in their own homes with care and support. The Royal Devon and Exeter Clozapine Service was set up in 2010. With Dr Sarah Jackson, a movement disorder specialist, as the consultant and registered clozapine prescriber, the team ensuring that the service runs efficiently for people with Parkinson's disease also involves a designated pharmacist, Parkinson's disease nurse specialist, a designated secretary and liaison with primary care (both district nurses and the patient's general practitioner (GP)).

The consultant's role is to identify those who may benefit from clozapine and this is done either during clinic or in liaison with the Parkinson's disease nurses in the community. A patient information leaflet explaining the rationale behind its use and the side-effects is given out to patients and their families. The GP is asked to check a baseline 12-lead ECG and baseline blood tests. During treatment postural blood pressure is checked in clinic and then again in the community by the district nursing team. Occasionally patients are started on clozapine during an in-patient stay and the team ensures that the GP and district nursing team are are ready to continue with FBC and postural blood pressure monitoring in the community on discharge.

The biggest challenge is making sure patients have their blood tests on time. Communicating with care home staff, GP surgeries, community nurses or spouses/partners to ensure that bloods are taken regularly can be challenging. The coordinating of this process is managed by the team's secretary.

From an administrative perspective, the main points for ensuring an efficient clozapine service are:

• Have one person responsible for preparing the prescriptions for all the patients and one consultant who signs for them

• If the clozapine prescriber is away on annual leave, ensure that other consultant prescribers are not on leave at the same time, and if they are, then prepare prescriptions before the leave

• Make GPs aware of the importance of regular weekly blood tests at the start of the prescribing

• Do not issue prescriptions on a Monday, because problems would then occur on bank holiday Mondays

• If the GP is outside of the laboratory area, ensure that they send the weekly blood results to the team by email to ensure that their patient is having regular tests and that the results are checked by the team

• Plan ahead for longer bank holidays, such as Easter and Christmas, to make sure prescriptions are done well in advance because of problems with delays in the post around these busy times

• Have a system to log prescriptions that are needed in advance and record when prescriptions are sent to the pharmacy

• Impress on people how crucial it is to have ‘green’ blood test results and not to have treatment breaks: the risk of treatment breaks is that the patient needs to go down to the initiation dose after the break, and this could exacerbate their psychosis.

At the time of writing, the team has 10 patients with Parkinson's disease psychosis actively being treated with clozapine, and 45 patients have been treated since 2010. To date, there have been no problems with red or amber results. Although patients often develop hypersalivation, constipation and a postural drop, no clozapine prescription has been stopped as a consequence. The average dose used in this patient cohort is 12.5–25 mg once a day.

Clozapine initiation at the Parkinson's Service Specialist Assessment and Rehabilitation Centre, Derby – Dr Rob Skelly and Dr Christine Taylor

Parkinson's UK funded a 1-year quality improvement project in Derby, for direct psychiatrist input one session per week into the multidisciplinary Parkinson's disease service (Taylor Reference Taylor, Johnson and Marsh2020). It quickly became evident that there was an unmet clinical need for access to clozapine.

This quality improvement project offered an ideal opportunity for reflection and investigation into the barriers to setting up such a service. The project benefited from having professionals in both the physical health and mental health trusts who could understand the logistics more easily and look for solutions to set up a service.

As a team we brainstormed possible models of care, also using the expertise of the mental health trust's senior pharmacists. There was already an infrastructure in place within the mental health trust to monitor patients on clozapine and provide weekly prescriptions. We identified that the number of people who would benefit from clozapine for their Parkinson's psychosis was likely to be very small.

It therefore appeared logical to use the infrastructure already in place for prescribing and blood results monitoring. This was set up using a service line agreement which, given the small number of patients and low costs of clozapine, amounts to a nominal sum of only several hundred pounds a year.

The team agreed that suitability for clozapine should be assessed in the Parkinson's clinic, so that this could occur alongside review of other anti-Parkinsonian medication.

We recognised that we would need a clear pathway to guide professionals and that there would need to be a named prescriber registered with the Clozaril Patient Monitoring Service (CPMS). As funding for ongoing psychiatric input was not guaranteed, we agreed that the Parkinson's consultant would also need to be registered as a named prescriber so that the service could continue in the absence of psychiatric input within the Parkinson's clinic.

As the service spanned the physical health trust and the mental health trust we sought and received approval from the drug and therapeutics committees of both trusts and the local clinical commissioning group.

We identified the training needs of staff in the Parkinson's clinic and developed a training presentation for them covering the key points with which they needed to be familiar. We also developed a clozapine patient record. The model, which we are now embedding, is outlined in the next section.

The logistics of the model

Patients will be seen in the multidisciplinary clinic on a Friday afternoon following referral from the treating specialist (geriatrician or neurologist). This assessment will involve a review of treatments tried so far and review of their anti-Parkinsonian medication. They will be assessed for suitability of community initiation of clozapine and factors considered will include whether they have someone living with them at least until treatment is established and that they must be willing to attend frequent appointments, including at least two visits to the Parkinson's clinic per week, once for blood testing and the other to collect weekly medication. The decision to proceed with a trial of clozapine will be made collaboratively with the patient and carer and the full multidisciplinary team.

If suitable, the patient will be registered with CPMS and dispensing pharmacy, and baseline bloods, ECG and physical observations checked. The dispensing pharmacy will also check that the referral meets suitability criteria. The patient will return the following Tuesday for a further blood test to ensure that there is a blood test within a few days of initiating treatment; they will then return on the following Friday to collect their first weekly prescription, which they will start on the Sunday evening.

Some patients are unsuitable for community initiation but are not in crisis. These individuals may be unable to access clozapine so have an unmet clinical need. They would be likely to continue on medications such as Quetiapine and Rivastigmine which have not fully resolved their symptoms.

Patients will attend for weekly blood testing on a Tuesday and attend on Friday for review and collection of a weekly prescription. The initial few reviews will be with the doctor and then subsequent reviews will be with the nursing team, who will issue the dispensed medication and review progress and potential side-effects.

A schedule is in place for monitoring of physical observations, which will be done at the Parkinson's clinic. Patients will commence medication on Sunday evening after collecting it on the previous Friday. They will then attend for physical observation checks on Monday and Tuesday mornings as a minimum and a plan then made for whether subsequent checks are needed later in that week. Any dose increase will occur on a Sunday and the physical observation monitoring will be repeated as above. Dose titration will be carried out very slowly, with patients starting on 6.25 mg and at least 2 weeks must elapse between dose increases. Medication is dispensed in a blister pack because a starting dose of 6.25 mg is a quarter of a 25 mg tablet and, if tablets were dispensed in a pot as quarter tablets, there is a risk that they would break up further.

Consideration will routinely be given to the management of common side-effects of clozapine, including postural hypotension, hypersalivation and constipation. Patients will be routinely provided with information leaflets about these side-effects. Patients will also be issued with an alert card to carry with them to show to other health professionals to explain that they are on clozapine should they become unwell.

Pros and cons of the three models

The main advantages of all three models are that patients can commence clozapine in the community and avoid a hospital admission and treatment decisions are made by their treating team, who know them well.

The main disadvantage of all three models is that patients who already have problems with postural hypotension or other physical health issues may not be suitable for out-patient initiation and may still require hospital admission. They alsorequire the patient to have adequate support at home, with a carer who can live with them at least during the initiation phase.

Conclusions

Management of Parkinson's psychosis is a complex area of clinical practice and untreated Parkinson's psychosis can carry with it a large burden on quality of life and is a key predictor of the need for 24 h care.

Treatment options are limited and clozapine is the most effective pharmacological treatment, with the best evidence base to support its use. However, in practice it can be difficult to prescribe owing to the monitoring requirements and the dispersal of the required expertise across several different healthcare services.

We hope that we have demonstrated that it is possible to set up safe out-patient clozapine initiation services that greatly benefit the small number of patients with Parkinson's psychosis. However, the operation of Parkinson's services varies across the UK, and individual services need to consider which model will best fit their own situation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Marie Hickman and Meara Brooks, clinical librarians at Kingsway Hospital, Derby, UK, for their help.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the paper.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 The percentage of patients with Parkinson's disease who develop psychosis is approximately:

a 5%

b 20–30%

c 60%

d 80%

e 100%.

2 The following treatments for Parkinson's psychosis are supported by NICE:

a quetiapine, clozapine, aripiprazole and olanzapine

b only clozapine

c quetiapine, clozapine, aripiprazole and rivastigmine

d quetiapine and clozapine

e quetiapine, clozapine and aripiprazole.

3 Blood monitoring reduces the risk of death from clozapine-related agranulocytosis to:

a 1 in 100 000

b 1 in 1000

c 1 in 15 000

d 1 in 10 000

e 1 in 150.

4 In a patient with Parkinson's psychosis it may be most helpful to consider stopping medications in the following order:

a anticholinergics, tricyclics, monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors, amantadine, dopamine agonists, catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitors, levodopa

b levodopa, COMT inhibitors, dopamine agonists, amantadine, MAO-B inhibitors, tricyclics, anticholinergics

c anticholinergics, levodopa, COMT inhibitors, dopamine agonists, amantadine, MAO-B inhibitors, tricyclics

d anticholinergics, tricyclics, levodopa, MAO-B inhibitors, amantadine, dopamine agonists, COMT inhibitors

e anticholinergics, levodopa, tricyclics, MAO-B inhibitors, COMT inhibitors, amantadine, dopamine agonists.

5 Regarding the UK licences for clozapine in Parkinson's psychosis which of the following is false:

a the starting dose must not exceed 12.5 mg daily

b the maximum dose must not exceed 100 mg daily

c dose titration can be done daily

d preferably clozapine should be given at bedtime in one dose

e the licences do not give any specific guidance about frequency of physical observation monitoring on commencing clozapine.

MCQ answers

1 c 2 d 3 d 4 a 5 c

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.