Akathisia is a common movement disorder characterised by psychomotor agitation that includes a sense of inner restlessness and non-purposive motor activity. These subjective and objective components of the syndrome are commonly assessed using the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (also known as the Barnes Akathisia Scale; Reference BarnesBarnes 1989). Akathisia is frequently associated with the use of antipsychotics (neuroleptics), but it can also complicate the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Other causes of akathisia include anxiety disorders, drug withdrawal or discontinuation states, early serotonin syndrome, restless legs syndrome, iron-deficiency anaemia and endocrinopathies. It is therefore important to find the underlying cause by identifying drug precipitants and associated psychopathology and excluding general medical causes.

The pathophysiology of akathisia is not fully understood, but a combination of hypodopaminergic and hyperserotonergic neurotransmission may be implicated (Reference Poyurovsky and WeizmanPoyurovsky 2001). This hypothesis is supported by the emergence of akathisia following the initiation of antipsychotics or SSRIs, but also from the observation that dopamine agonists can alleviate psychomotor agitation associated with restless legs syndrome (Reference Garcia-Borreguero, Stillman and BenesGarcia-Borreguero 2011).

Akathisia can have a significant negative impact on quality of life and is associated with increased suicidality (Reference Seemüller, Schennach and MayrSeemüller 2012). Treatment of this distressing condition is difficult and treatment options are limited. I therefore carried out a review of the literature to devise an evidence-based treatment algorithm.

Treatment strategies

The treatment of akathisia may be divided into two components:

-

change in antipsychotic medication

-

addition of another therapeutic agent.

Pragmatic changes to the antipsychotic regimen include:

-

reducing the dose (or withdrawal) of the antipsychotic

-

switching to a low-potency first-generation antipsychotic or a second-generation antipsychotic with a low potential for causing akathisia.

In practice, use of this strategy is limited by the potential for deterioration in mental state. In addition, analysis of the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) data found similar rates of akathisia among patients prescribed first-and second-generation antipsychotics (Reference Lieberman, Stroup and McEvoyLieberman 2005; Reference Miller, Caroff and DavisMiller 2008). Therefore, the identification of safe and effective medications to manage akathisia is imperative.

Literature search

A search of the Cochrane Library using the search term ‘akathisia’ found three Cochrane reviews of centrally acting β-adrenergic antagonists (beta-blockers), anticholinergics and benzodiazepines. I then performed a MEDLINE search (MeSH terms: akathisia, treatment; limits: English language, randomised controlled trial, human) to identify additional double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trials using these three agents. The results of this literature search are summarised in the following sections.

Centrally acting β-adrenergic antagonists

A Cochrane review in 2004 identified three randomised placebo-controlled trials (n = 51) of centrally acting beta-blockers (Reference Lima, Bacaltchuk and BarnesLima 2004a). The authors stated that there were insufficient data to recommend their use for the management of akathisia. In two 48 h studies using propranolol (60–80 mg), none of the 31 participants experienced full remission of akathisia (Reference Irwin, Sullivan and van PuttenIrwin 1988; Reference Kramer, Gorkin and DiJohnsonKramer 1988), but the drug was well tolerated and no one discontinued treatment. In a 72 h trial (n = 20) no statistically significant difference was found between the novel centrally acting beta-blocker ICI-118,551 and placebo for the outcome ‘no change/worse’ (Reference Adler, Duncan and AngristAdler 1989). No adverse events were reported. The findings of Lima et al’s review and meta-analysis (Reference Lima, Bacaltchuk and BarnesLima 2004a) are limited by the small data-set and short trial duration. There were also important methodological limitations: not all of the trials were explicit about the process of randomisation or the maintenance of double-blind conditions.

My MEDLINE search found one additional randomised placebo-controlled trial (n = 90) (Reference Poyurovsky, Pashinian and WeizmanPoyurovsky 2006) since the publication of the 2004 Cochrane review. This involved a 7-day double-blind trial of propranolol (80 mg) and used the Barnes Akathisia Scale (BAS) to assess treatment response. This trial had two treatment arms (propranolol and mirtazapine) compared with placebo. The results of the mirtazapine arm are discussed below. Propranolol resulted in a significant reduction in akathisia symptoms (BAS score improved by 29% over the trial period). However, 27% of the participants discontinued propranolol because of non-response and 17% withdrew because of hypotension and bradycardia.

Anticholinergics

A Cochrane review (Reference Lima, Weiser and BacaltchukLima 2004b) systematically searched the literature to identify randomised placebo-controlled trials investigating the role of anticholinergics in antipsychotic-induced akathisia. The authors found no relevant trials and concluded that there was no reliable evidence to support or refute the use of anticholinergic agents.

My MEDLINE search yielded one short-term placebo-controlled trial (Reference Baskak, Atbasoglu and OzguvenBaskak 2007): this reported no difference in outcome between intramuscular biperiden and placebo.

The use of anticholinergics is also limited by an increased risk of related side-effects.

Benzodiazepines

A Cochrane review (Reference Lima, Soares-Weiser and BacaltchukLima 2002) identified two randomised placebo-controlled trials (n = 27) using clonazepam (0.5–2.5 mg daily), a long-acting benzodiazepine (Reference Kutcher, Williamson and MacKenzieKutcher 1989; Reference Pujalte, Bottaï and HuëPujalte 1994). Overall, clonazepam was more effective in achieving ‘partial remission’ by day 7, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 1.2 (Reference Lima, Soares-Weiser and BacaltchukLima 2002). ‘Partial remission’ was defined as an improvement in BAS or Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS) scores by at least 50%. No adverse events or withdrawals were reported in both trials. Again, the findings of Lima et al’s review were limited by the small data-set and not all of the trials being explicit about the randomisation process or the maintenance of double-blind conditions. Tolerance and dependence are also considerations, especially when thinking about long-term treatment.

My MEDLINE search found no relevant randomised placebo-controlled trials since the Cochrane review.

Mirtazapine: a novel therapeutic option

The MEDLINE search found a number of small randomised controlled trials investigating other akathisia treatments, including trazodone (Reference Stryjer, Rosenzcwaig and BarStryjer 2010), vitamin B6 (Reference Lerner, Bergman and StatsenkoLerner 2004; Reference Miodownik, Lerner and StatsenkoMiodownik 2006) and mianserin (Reference Poyurovsky, Shardorodsky and FuchsPoyurovsky 1999), each of which demonstrated therapeutic benefit. However, there appears to be a growing body of data suggesting that mirtazapine, a presynaptic α2 receptor and specific serotonin antagonist, may have a greater role to play in the management of akathisia. The search also identified two randomised placebo-controlled trials using mirtazapine (total sample: 116), and these are discussed below. It is important to note that mianserin and mirtazapine have similar pharmacological actions.

A double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial of mirtazapine (n = 26) of 5 days’ duration was performed in 2003 (Reference Poyurovsky, Epshtein and FuchsPoyurovsky 2003). Symptom severity was assessed using the BAS. The randomisation sequence was stated: 13 patients received the active drug (mirtazapine 15 mg daily); 54% in the treatment group had a reduction in BAS scores of ≥2. This improvement in symptoms was statistically significant (P = 0.004). Complete remission of symptoms occurred in 31% of the mirtazapine group; 23% of the group withdrew from the study before the day 3 assessment because of non-response or sedation.

A second randomised placebo-controlled trial (n = 90) of 7 days’ duration was performed in 2006 (Reference Poyurovsky, Pashinian and WeizmanPoyurovsky 2006). The trial had two active groups (mirtazapine 15 mg daily and propranolol 40 mg daily) and a placebo group. The randomisation sequence was stated. Symptom severity was again assessed using the BAS. I discussed the propranolol results above. In the mirtazapine group (n = 30), the drug resulted in a statistically significant reduction in akathisia symptoms (BAS score improved by 34% over the trial period; P = 0.012). Ten patients in the mirtazapine group (33%) experienced a complete remission in symptoms; 36.7% experienced drowsiness, but this did not precipitate study withdrawal; 23% discontinued treatment early because of non-efficacy.

An evidence-based treatment algorithm

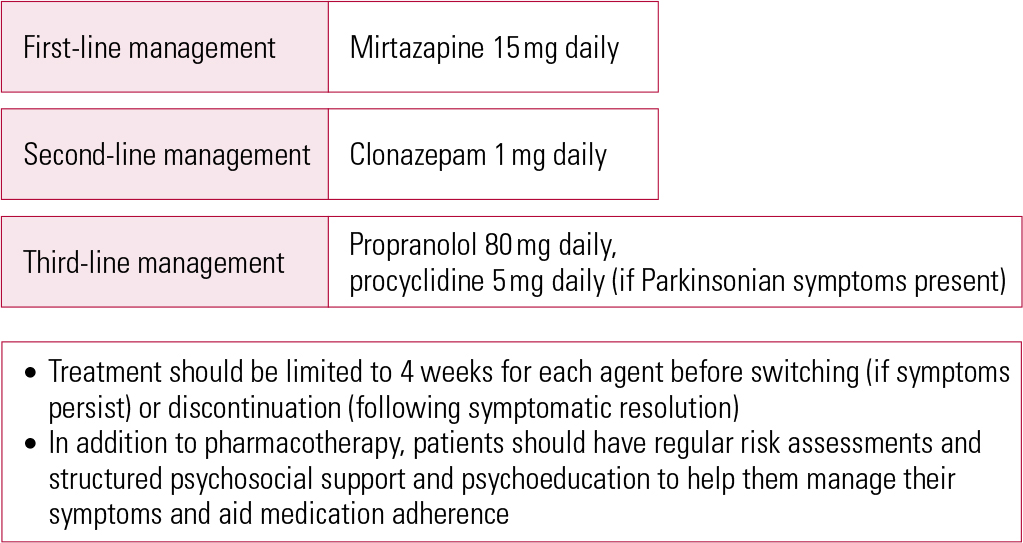

As this literature search shows, the evidence at present is limited and there is need for further evaluative studies. In the meantime, I propose the treatment algorithm shown in Fig. 1, which is based on the available evidence, to maximise therapeutic effect and reduce adverse effects. Note that, in keeping with best practice, this includes psychosocial support and psychoeducation to help patients manage their symptoms and adhere to their medication.

FIG 1 Evidence-based treatment algorithm for the management of antipsychotic-induced akathisia.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Peter Liddle (Professor of Psychiatry, University of Nottingham) and Dr Verghese Joseph (Stamford Resource Centre) for reviewing the first draft of this article.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.