Research has consistently found that people using mental health services have experienced high rates of trauma in childhood or adulthood (e.g. Kessler Reference Kessler, McLaughlin and Green2010) and that these rates are higher than in the general population (e.g. Mauritz Reference Mauritz, Goossens and Draijer2013). It has also been found that people using mental health services are more likely to have experienced violence or trauma in the previous year than the general population (e.g. Khalifeh Reference Khalifeh, Moran and Borschmann2015).

A major retrospective study of over 17 000 predominantly White middle-class Americans found not only that childhood trauma is prevalent, but also that it influences physical, mental and emotional health as adults and can shorten life expectancy (e.g. Felitti Reference Felitti, Anda and Nordenberg1998). Traumatic effects are cumulative: the more traumatic experiences a person is exposed to, the greater the impact on mental and physical health (e.g. Shevlin Reference Shevlin, Housten and Dorahy2008). Furthermore, having a trauma history is associated with poorer outcomes for survivors, including a greater likelihood of attempting suicide, of self-harming, longer and more frequent hospital admissions and higher levels of prescribed medication (e.g. Read Reference Read, Harper and Tucker2007; Mauritz Reference Mauritz, Goossens and Draijer2013). There is also growing evidence that childhood trauma shapes our neurobiology. Box 1 describes how contemporary neuroscientific research is improving our understanding of the ways in which trauma affects individuals. This further highlights the interaction between the social, personal and biological realms that make up the ‘triangle of well-being’ and that cannot exist in isolation (Siegel Reference Siegel2012).

BOX 1 Contemporary neuroscientific research into the effects of trauma

Neuroscientific research has demonstrated the impact of trauma on the brain, including changes to the sensory systems, grey-matter volume, neural architecture and neural circuits (e.g. Read Reference Read, Fosse and Moskowitz2014). There is also a growing body of evidence that trauma leaves an imprint not only on the brain but on the mind and body too, signifying the value of broadening our understanding of and approach to healing trauma (Van der Kolk Reference Van der Kolk2014).

Experiencing complex childhood trauma creates a ‘template’ through which future inputs are processed; neural responses become sensitised and can be reactivated by seemingly minor stresses (Van der Kolk Reference Van der Kolk2005). This means that trauma survivors are ‘primed’ to respond to situations and relationships that embody characteristics of past traumatic events or in which there is a perceived threat. This can also be understood through having a narrower ‘window of tolerance’, with the stress thermostat being set too high or too low and being easily triggered into states of hyperarousal or hypoarousal by external cues (Siegel Reference Siegel1999).

Survival responses include fight, flight and freeze. These defence responses of the autonomic nervous system can lead people to become dysregulated into a hyperarousal state, in which feelings of terror and panic trigger the use of coping strategies such as substance misuse and self-injury to reduce distress (Raju Reference Raju, Corrigan and Davidson2012). These self-destructive behavioural adaptions are often linked to low self-esteem, shame and guilt. Other effects include hearing voices and eating difficulties. These responses may appear extreme or abnormal when a trauma history is not taken into account, and can be misconstrued as symptoms of mental illness. Likewise, explosive anger, walking out of or avoiding services, extreme apathy, overcompliance and silent crying potentially need to be recognised and understood as adaptive responses from trauma. These examples of emotional dysregulation can benefit from emotional understanding and adaptive regulation strategies (Powers Reference Powers, Cross and Fani2015). Learning to self-regulate high states of arousal and intense emotions can heal the effects of trauma (Levine Reference Levine2010).

In addition to improving self-regulation, trauma survivors benefit from developing healthy relationships, which they may have lacked during childhood, in particular secure attachment to their primary caregiver. Through relationships, trauma survivors can learn to feel safe, trust others, learn new ways of relating to people and develop self-compassion (Van der Kolk Reference Van der Kolk2014). The biomedical approach and associated interventions fail to acknowledge the value of healthy and meaningful relationships, which mitigate the destructive impact of trauma (Van der Kolk Reference Van der Kolk2005).

Trauma is costly in both human and economic terms. Economic costs include those from lost employment, presenteeism (being at work, but not functioning well), reduced productivity and the provision of mental health and other services (e.g. McCrone Reference McCrone, Dhanasiri and Patel2008). But the real impact is on people and society. Trauma not only affects individuals in the present, but crosses generations socially, psychologically and, recent evidence suggests, epigenetically (e.g. Yehuda Reference Yehuda, Daskalakis and Bierer2016).

Trauma-informed approaches in mental healthcare have a fairly extensive literature on the underpinning theory, along with an emerging evidence base; a small number of studies have explored the effectiveness of such approaches and found reductions in symptoms and in the use of seclusion and restraints, as well as improvements in coping skills, physical health, retention in treatment and shorter in-patient stays (Sweeney Reference Sweeney, Clement and Filson2016). Trauma-informed approaches also offer hope to survivors that the ongoing human costs of trauma can be overcome (e.g. Filson Reference Filson, Russo and Sweeney2016).

What is trauma?

Both DSM-5 and the forthcoming ICD-11 have refocused clinical attention on the definition and recognition of trauma and its effects. In DSM-5, trauma and related mental health conditions are understood as being triggered by external traumatic events: specifically, exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury or sexual violence through direct or indirect experiencing or witnessing of the event/s (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Extensive consultation led to a broad list of symptoms within post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and related diagnoses in DSM-5 (Friedman Reference Friedman2013). In contrast, the current draft of the ICD-11 includes complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) (e.g. Karatzias Reference Karatzias, Cloitre and Maercker2018); to be diagnosed with CPTSD, people must meet all diagnostic criteria for PTSD and additionally express difficulties in affect regulation, self-concept/worth and relationships/attachments.

The conceptualisation of responses to trauma as disorders with identifiable aetiology and symptoms, as opposed to natural human reactions to extreme adversity, is highly contested (e.g. McHugh Reference McHugh and Treisman2007). For instance, the chair of the DSM-IV Task Force has argued against the over-medicalisation of human experience (Frances Reference Frances2013). Alternative ways of conceptualising trauma and its effects include the ‘Power Threat Meaning Framework’, a psychosocial narrative based alternative to psychiatric diagnosis, (Johnstone Reference Johnstone, Boyle and Cromby2018) and that of the US Federal organisation SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2014), set out in Box 2.

BOX 2 SAMHSA's definition of trauma

‘Individual trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual's functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional or spiritual well-being.’

(Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2014: p. 7).

SAMHSA's conceptualisation (Table 1) encompasses three factors: the trauma event, which need not be life threatening, thus acknowledging that, as social animals, we can be traumatised by acts that threaten our psychological/social integrity; the way in which the event is experienced (the intra- and interpersonal context); and its effects.

TABLE 1 Understanding trauma

Based on Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2014).

Notably, these alternative conceptualisations acknowledge the role of social traumas, arguably overlooked in DSM-5 and the proposed ICD-11. For instance, poverty has sometimes been described as ‘the cause of the causes’ of mental distress (Read Reference Read2010): the latest UK Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey found that, among people receiving Employment and Support Allowance (for people who cannot work for health reasons), nearly half had attempted to take their own life (NHS Digital 2016). It has also been found that Black people are simultaneously more likely to experience trauma (e.g. Hatch Reference Hatch and Dohrenwend2007), are overrepresented in the mental health system, and receive the most negative and adversarial responses (such as compulsory treatment) which are known to cause iatrogenic harm (e.g. Morgan Reference Morgan, Mallett and Hutchinson2004; Mohan Reference Mohan, McCrone and Szmukler2006). Trauma-informed approaches to mental healthcare places individuals in their social and political contexts in order to understand how complex traumas affect past and current states. However, there is concern among some survivors that, in adopting a broad conceptualisation of trauma, the term could lose its meaning, with anything and everything subsumed under its label (Taggart, personal communication, 2018). Consequently, the gravity of the experiences and effects of trauma should be acknowledged, with individuals able to develop their own narratives (Taggart, personal communication, 2018).

To effectively implement trauma-informed approaches in routine healthcare (in contrast to trauma-specific services), trauma does not need valid and reliable diagnosis or measurement, because principles of engagement are implemented for all service users, regardless of whether they have survived trauma. Trauma-informed approaches are, in effect, a process of organisational change that creates recovery environments for staff, survivors, their friends and allies, with implications for relationships. It is also acknowledged that experiences of trauma are widespread across all demographics of society and have an impact not on only the service user, but also on staff, allies, family members and others; this knowledge underpins our ability to be compassionate.

Trauma in the mental health system

‘No intervention that takes power away from the survivor can possibly foster her recovery, no matter how much it appears to be in her immediate best interest’ (Herman Reference Herman1998).

Retraumatisation

The current mental health system tends to conceptualise extreme behaviours and distress as symptoms of mental illnesses, rather than as coping adaptations to past or current traumas. As a consequence, responses to people in extreme distress can be unhelpful and even (re)traumatising. Retraumatisation – meaning to become traumatised again – occurs when something in a present experience is redolent of past trauma, such as the inability to stop or escape a perceived or actual personal threat. Evident forms of retraumatisation include seclusion, restraint, forced medication, body searches and round-the-clock observation. Box 3 gives an account of a woman experiencing 24 h observation on a psychiatric in-patient ward.

BOX 3 Case vignette: Claire

Claire has been admitted to hospital following an attempt to take her own life. Staff are concerned that she will either self-harm or attempt suicide again and have set up round-the-clock observation. Claire is naturally private and finds the constant presence of another person during personal care, eating and sleeping humiliating. The staff members observing Claire do not interact with her much and, rather than feeling supported, Claire feels as though she is being punished. She has few opportunities to talk about the things that led her to feel suicidal. The constant observation and lack of choice also trigger the feelings associated with memories of unwanted intrusions and lack of privacy in childhood. This leaves Claire feeling more frightened, desperate and out of control.

There is some empirical evidence that service users frequently witness or experience traumatic events in psychiatric in-patient settings (seclusion, restraint, physical assault, etc.) (e.g. Freuh Reference Freuh, Knapp and Cusack2005; Cusack Reference Cusack, Cusack and McAndrews2018) and general psychiatric settings (e.g. Örmon Reference Örmon and Hörberg2017), and that these events are harmful to those who experience and witness them. Service users and those who support them cite lack of understanding of trauma as a barrier to reducing seclusion and restraint (Brophy Reference Brophy, Roper and Hamilton2016). There can also be a lack of training in alternative approaches to responding to distress, and a lack of recognition of the role of coercion in perpetuating crisis and legitimising force. Using controlling practices can, of course, also be traumatising for staff enacting or observing them, further supporting the need for adopting alternative, less traumatising approaches.

Retraumatisation can also relate to people's experiences of historical or cultural trauma, such as pathologising an individual's response to racism (Jackson Reference Jackson2003). Less obvious forms of (re)traumatisation include the use of ‘power-over’ relationships that replicate power and powerlessness by disregarding the experiences, views and preferences of the individual. Butler and colleagues explain:

‘There may be messages implicit in the manner or communication of care delivery that can also be triggering for a trauma survivor if he or she recapitulates aspects of the betrayal, boundary violation, objectification, powerlessness, vulnerability, and lack of agency experienced during the original trauma’ (Butler Reference Butler, Critelli and Rinfrette2011).

Box 4 describes a woman's experiences of lacking choice in perinatal services.

BOX 4 Case vignette: Emma

Emma, a first-time mother with a 4-month-old baby, has been referred to a specialist perinatal service by her general practitioner. During her first appointment with the perinatal psychiatrist, Emma is asked about her life history and discloses experiences of childhood abuse. She explains that she is feeling overwhelmed and hopeless, and fears that she is not fit to parent her baby. Emma says that she would like to be in touch with women who are going through similar experiences, as she feels it would give her strength to know she is not alone and would help her to build a support network. The perinatal psychiatrist feels that Emma is experiencing post-natal depression and prescribes an antidepressant. Emma is breastfeeding and does not want the antidepressant because it will pass to the baby. However, the psychiatrist says that the harm done to the baby by Emma's depression will be far greater than the harm done by the medication and explains that this is the only treatment available to her. Emma is left feeling confused and guilty, believing that either choice she makes will harm her child. Where previously she had feared that she was unfit to be a mother, now she is convinced. Emma is not referred to peer support as the perinatal service does not facilitate this. Instead, she is given a prescription and has an appointment in one month's time for monitoring.

Vicarious trauma

Vicarious trauma usually refers to the effect of working with traumatised people on practitioners, and it includes compassion fatigue, countertransference and burnout (e.g. Schauben Reference Schauben and Frazier1995). But ‘trauma-uninformed’ organisations can themselves cause vicarious trauma in staff. For example, relying on seclusion and restraint to manage distress is not only harmful to the person experiencing it: clinicians may learn to rely on power rather than their relational capacity to engage collaboratively, particularly where trauma-uninformed organisations place a high priority on risk management. This can have an enormous negative effect on staff members, shaping and reconstructing identity (Knight Reference Knight2015) from ‘I am a compassionate, caring person who is here to help others’ to ‘Just get me through one more day’. Using power to manage extreme behaviours can cause service users to fear and distrust staff, resulting in poor engagement and thus potentially frustrated and dissatisfied staff who rely even more heavily on power and control. Sandra Bloom has discussed these issues in terms of ‘parallel processes’ (Bloom Reference Bloom2006).

What are trauma-informed approaches and why do we need them?

Trauma-informed approaches were initially developed in North America and are now receiving increasing global attention, including pioneering work by A. K. in the UK. They are based on a recognition and comprehensive understanding of the widespread prevalence and effects of trauma. This leads to a fundamental paradigm shift from thinking ‘What is wrong with you?’ to considering ‘What happened to you?’ (Box 5). Rather than being a specific service or set of rules, trauma-informed approaches are a process of organisational change aiming to create environments and relationships that promote recovery and prevent retraumatisation.

BOX 5 The key paradigm shift in trauma-informed approaches

The fundamental shift in trauma-informed approaches is moving from thinking ‘What is wrong with you?’ to considering ‘What happened to you?’ (Foderaro, cited in Bloom Reference Bloom1995). This means that service providers understand and acknowledge the widespread prevalence and effects of trauma on people and incorporate this into their practice. However, as Taggart observes, this can only be considered an improvement if it does not become another form of imposition (Taggart, personal communication, 2018).

Trauma-specific services

Trauma-specific support can be distinguished from trauma-informed approaches. In trauma-specific services, the individual has a known history of trauma and interventions directly address its effects (e.g. eye-movement desensitisation and reprocessing). Conversely, trauma-informed approaches are founded on an understanding of the widespread exposure to trauma among service users and also among providers. (Esaki Reference Esaki and Larkin2013).

The principles of trauma-informed approaches

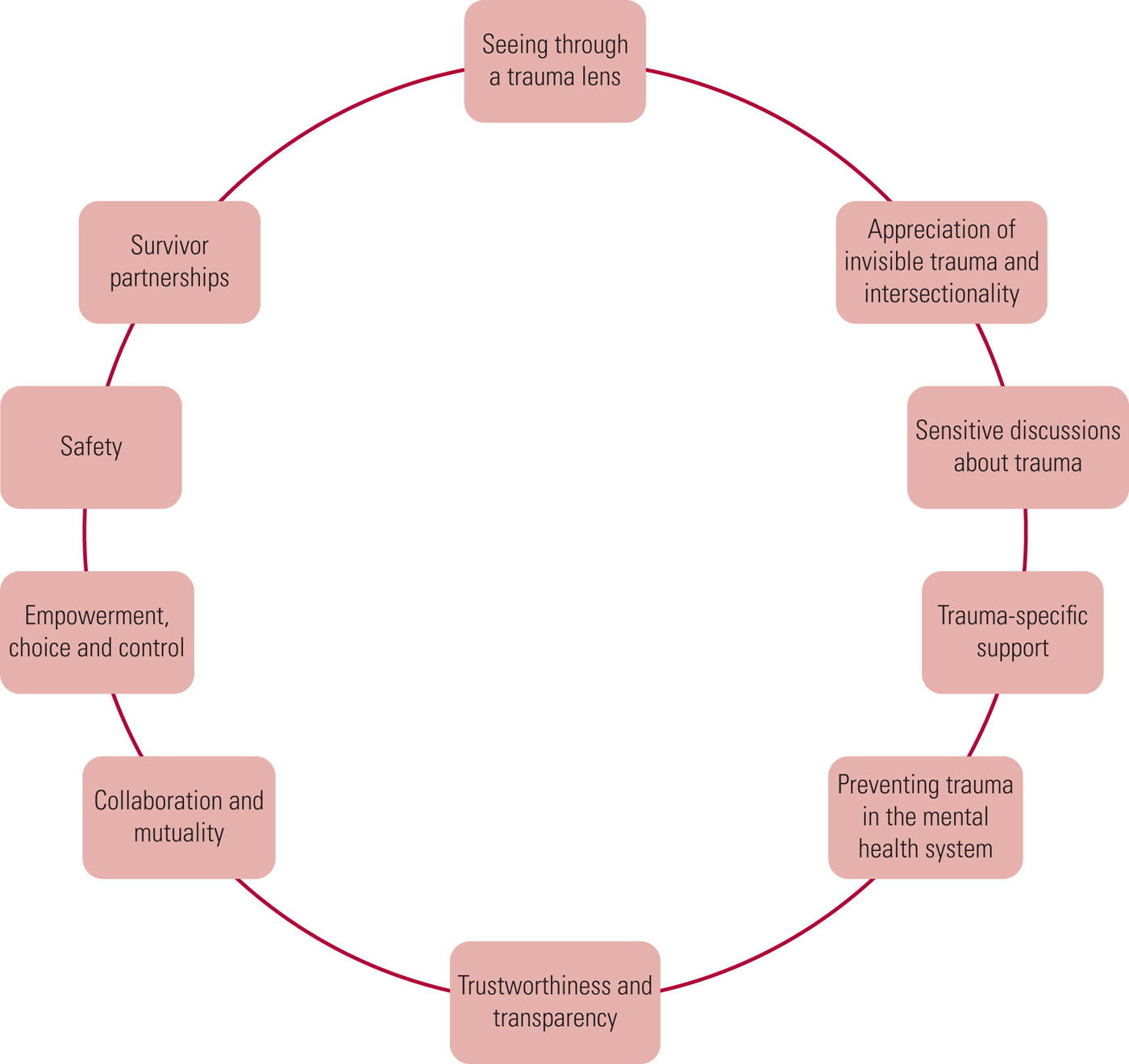

The basic principles of trauma-informed approaches include the following (adapted from Elliot Reference Elliot, Bjelajac and Fallot2005; Bloom Reference Bloom2006; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2014) (Fig. 1).

FIG 1 Ten key principles of trauma-informed approaches (adapted from Elliot Reference Elliot, Bjelajac and Fallot2005; Bloom Reference Bloom2006; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2014).

Seeing through a trauma lens

Trauma-informed practices acknowledge and understand the high prevalence, common signs and widespread effects of trauma. There is an understanding of the ways in which trauma can influence emotions and therefore behaviour, leading to the development of coping strategies that can seem excessive, dangerous or harmful without a comprehensive understanding of the multiple consequences of trauma (Box 1).

Appreciation of invisible trauma and intersectionality

A broad-based understanding of trauma is adopted, involving an appreciation of community, social, cultural and historical traumas such as racism, poverty, colonialism, disability, homophobia and sexism and their intersectionality. Services understand the context and conditions of people's lives and are culturally and gender competent. To achieve this, staff remain open-minded and consider all perspectives.

Sensitive discussions about trauma

When service users are asked about trauma, this is done in respectful, sensitive, timely and appropriate ways, and the individual is offered a clear choice regarding whether or not to answer (Box 6). There is an understanding of the potential retraumatisation caused by describing traumatic events, and the potential damage caused by repeating one's story when nothing changes (Filson Reference Filson2011). Additionally, survivors may not recognise that past events have had adverse, lasting effects on them, for instance, because of definitions of trauma, the normalisation of traumatic events within families and communities or an inability to recall early experiences.

BOX 6 Asking about trauma and abuse

It is very rare for trauma survivors to spontaneously disclose their trauma experiences, yet mental health practitioners often fear asking people about their past or current experiences of trauma (Read Reference Read, Hammersley and Rudegeair2007). Read and colleagues report a range of reasons for this reluctance to ask, including: a need to focus on immediate concerns; fear of causing distress; fear of vicarious traumatisation; holding a biogenetic causal model of mental distress; and lacking training. They recommend that practitioners:

• ask everyone about their experiences of trauma and abuse

• ask at the initial assessment, but not during a crisis

• ask in the context of the person's general psychosocial history

• preface trauma questions with a brief normalising statement

• use specific questions, with clear examples.

Questions should be asked sensitively and at the person's pace. Service users should be reassured that they do not have to disclose abuse or trauma if they do not want to and that they can refuse to answer questions. It is important to have an understanding of dissociation, commonly associated with trauma, and to be sensitive to this. When individuals choose not to disclose traumatic experiences or are simply unable too, staff need to be receptive to this and be able to recognise the signs associated with previous trauma, without the need for full disclosure. Where a person discloses trauma and abuse, Read and colleagues recommend that the practitioner responds in the following way:

• reassure the person that disclosure is a good thing

• do not try to ascertain the details of the trauma or abuse

• ask if anyone has been told previously and how that went

• offer trauma-specific support and know how to refer people to it

• ask whether the trauma is related to their current difficulties

• check their current safety (freedom from abuse)

• check the person's emotional state at the end of the session

• offer a follow-up appointment.

(Based on Read et al Reference Read, Hammersley and Rudegeair2007)

Pathways to trauma-specific support

When survivors are able to report a trauma history, and trauma-specific services are requested or desirable, these services are available, or facilitated through cross-agency coordination.

Preventing trauma in the mental health system

Trauma-informed practices understand that the fundamental operating principles of coercion and control in mental health services can lead to (re)traumatisation and vicarious trauma. Deliberate steps are taken to eliminate and/or mitigate potential sources of coercion and force, and accompanying triggers.

Trustworthiness and transparency

Trusting relationships are built between staff and service users through an emphasis on openness, transparency and respect. This is essential because many trauma survivors have experienced secrecy, betrayal and/or ‘power-over’ relationships.

Collaboration and mutuality

Trauma-informed practices understand that there is a unilateral aspect to relationships in mental health care, with one person acting as helper to a ‘helpee’. These roles can replicate power imbalances and reinforce a sense of disability and helplessness in the helpee (Mead, personal communication, 2018). Thus, relationships and interventions strive for collaboration through transparency, authenticity and an understanding of what both people see as helpful.

Empowerment, choice and control

Trauma-informed practices use strengths-based approaches that are empowering and support individuals to take control of their lives and service use. Such approaches are vital because many trauma survivors will have experienced an absolute lack of power and control. Adaptations to trauma are emphasised over symptoms, and resilience over pathology (Butler Reference Butler, Critelli and Rinfrette2011).

Safety

Central to trauma experiences are threats to the person's safety and often to the integrity of their identity. Consequently, trauma-informed practices ensure that the staff member and the individual are emotionally and physically safe, with both people defining what this means and negotiating it relationally. This extends to physical, psychological, emotional, social, gender and cultural safety, and is created through measures such as informed choice and cultural and gender competence.

Survivor partnerships

Trauma-informed practices strive to achieve mutual and collaborative relationships between staff and service users through partnership working. Additionally, services can be led and delivered by people with direct experience of trauma and mental health service use.

Clearly, within trauma-informed approaches, endemic trauma is a motivator for organisational change and improved relationships, alongside an attempt to address trauma-related needs.

Trauma-informed approaches and contemporary policy and good practice

Trauma-informed principles overlap with a number of other good practice approaches. For instance, principles of collaboration, empowerment, informed choice and control have much in common with shared decision-making (e.g. Elwyn Reference Elwyn, Frosch and Thomson2012) and service user involvement, for example in care planning (e.g. Grundy Reference Grundy, Bee and Meade2016). Cultural and gender competence are well-established good practice principles (e.g. Schouler-Ocak Reference Schouler-Ocak, Graef-Calliess and Qureshi2015; Against Violence and Abuse 2017). Peer support is emerging as an important element of UK mental healthcare (e.g. Gillard Reference Gillard, Edwards and Gibson2013), with the principles of trauma-informed approaches in line with grassroots peer support practice (Mead Reference Mead and McNeil2006). Research and clinical efforts to improve acute wards also overlap with the principles of trauma-informed practice (e.g. Star Wards, https://www.starwards.org.uk/; Safewards, www.safewards.net), including efforts to reduce control and restraint (e.g. O'Hagan Reference O'Hagan, Divis and Long2008).

Implementing trauma-informed approaches may enable commissioners and health services to meet national policy recommendations. For instance, shared decision-making, increased choice, positive care experiences and improved recovery rates are part of the Five Year Forward Plan (Mental Health Taskforce 2016; NHS England 2016). In Scotland, trauma-informed approaches are fundamental to the implementation of the knowledge and skills framework ‘Transforming Psychological Trauma’ (NHS Education for Scotland 2017). Public Health Wales (2015) has produced a series of reports on adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), supporting the need for trauma-informed practice. Moreover, trauma-informed services are likely to be in a state of readiness for major incidents similar to the Manchester Arena bombings or the Grenfell Tower fire in London.

Barriers to creating trauma-informed relationships in mental health services

Before we describe the relational aspects of trauma-informed approaches, we would first like to explore systemic barriers that can prevent individual staff from fully engaging in trauma-informed relationships. We do so while acknowledging that many staff will engage in trauma-informed practices without perhaps naming them as such.

Barriers related to working in the UK public sector:

• austerity, underfunding and lack of resources, particularly staff shortages, can make the working environment stressful and at times overwhelming

• the volume of paperwork can reduce time for clinical activities, developing relationships and interacting with service users

• grappling with top-down, unpredictable and frequent change in public services, coupled with a regular plethora of new initiatives to implement, can lead to confusion and exhaustion (Sweeney Reference Sweeney, Clement and Filson2016)

• low morale and high staff turnover, particularly on acute psychiatric wards, can prevent meaningful long-term change.

Barriers related to a lack of supportive organisational cultures:

• organisational cultures can fail to support, or can actively conflict with, trauma-informed working methods; an example is a risk-averse culture that encourages staff to engage with service users using ‘power-over’ approaches

• a general lack of supervision, training and support, coupled with a specific lack of training on trauma-informed approaches

• little opportunity to reflect on practices and feedback among staff, and with service users

• consequent confusion and perhaps apprehension regarding introducing trauma-informed principles into individual practice beyond the reduction of seclusion and restraint (Muskett Reference Muskett2014).

Barriers relating to the continuing dominance of biomedical models of mental distress:

• reluctance to shift from biomedical causal models of mental distress to holistic biopsychosocial models, or a lack of exposure to alternatives

• strong biomedical focus of training for mental health professionals, making it difficult to challenge biomedically dominated cultures

• the biomedical emphasis means that the social and psychological are neglected, leading to lack of investment in diverse mental health services and treatments

• little exposure to the notion of social, urban, historical and cultural trauma

• the historical underpinnings of psychology, including behaviourism with its erroneous assumptions that empathy and compassion reward bad behaviour

• understanding the extent of trauma exposes human nature as cruel and perverse, challenging our worldview and making it difficult to accept that reality.

In addition, research has identified a number of barriers to enquiring about childhood abuse, including a belief that people want to be asked about their experiences by someone of the same gender or cultural background, and holding biogenetic causal models of mental distress (Young Reference Young, Read and Barker-Collo2001) (Box 6).

Identifying these barriers can signpost some of the changes needed to support staff to work fully in trauma-informed ways (for more on overcoming these barriers see Sweeney Reference Sweeney, Clement and Filson2016).

Overcoming the barriers to create trauma-informed relationships in mental health services

Notwithstanding these barriers, many practitioners are not employed in trauma-informed organisations yet want to practice trauma-informed approaches, recognising their benefits. Butler and colleagues have given an excellent overview of the ways practitioners can ensure that principles of safety, trustworthiness, choice, collaboration and empowerment are enacted (Butler Reference Butler, Critelli and Rinfrette2011). We consider two further key areas relating to understanding the impact and universality of trauma.

‘What happened to you?’ – asking about trauma

Although the shift from thinking ‘What is wrong with you?’ to considering ‘What has happened to you?’ is an orienting one, well-timed and paced trauma enquiries are nonetheless critical. Making such enquiries is likely to uncover the scale of trauma and abuse experienced by service users, providing further impetus for the need to adopt trauma-informed approaches.

Box 6 gives an overview of how practitioners can ask about abuse based on a major paper by Read and colleagues (Read 2007). It suggests that all mental health service users should be asked about their experiences of trauma and abuse, and in the UK this is now considered standard practice (e.g. Rose Reference Rose, Freeman and Proudlock2012). However, a recent systematic review of international research found that between 0 and 22% of service users report being asked about abuse experiences (Read Reference Read, Harper and Tucker2017). Similarly, a substantive literature review found that mental health professionals do not routinely ask people in acute psychiatric settings about their experiences of childhood sexual abuse (Hepworth Reference Hepworth and McGowan2013). This may in part be because practitioners feel insufficiently equipped to respond effectively to disclosures (Rose Reference Rose, Trevillion and Woodall2011). A study involving a small number of psychological therapists in early intervention services reported that asking about abuse was related to the therapists' knowledge of the literature on trauma-based models of mental distress, whether they emphasised therapeutic relationships with service users, and their personal qualities, skills and confidence (Toner Reference Toner, Daiches and Larkin2013). Moreover, holding a psychosocial model of psychosis was an essential foundation for conducting trauma assessments. There is promising research suggesting that, with training and support, staff can gain the confidence and knowledge needed to effectively assess and treat trauma (Walters Reference Walters, Hogg and Gillmore2015).

However, it is not sufficient simply to ask, as asking about abuse in trauma-uninformed ways can be retraumatising (Box 6). This includes asking without making sure that the individual feels they can refuse to answer, asking overly detailed questions, not knowing where to refer an individual who reveals past trauma and not understanding how to respond. It is therefore critical that practitioners are trained not only in making sensitive routine enquiries about trauma experiences, but also in how best to respond to disclosures and how to translate the information into meaningful individualised services; this clearly means that there should be appropriate services to refer survivors to (Scott Reference Scott, Williams and McNaughton Nicholls2015). Clinicians should also be clear that they may have a duty to breach confidentiality, for instance where the perpetrator poses a current risk to others (Rouf Reference Rouf, Waites and Weatherhead2016). For service users, being asked extensive questions about trauma without appropriate response and follow-up support can be experienced as a form of silencing and/or as akin to having a wound opened in surgery and left exposed.

Understanding coping adaptations

Many of the behaviours displayed by trauma survivors can seem perplexing, dangerous or bizarre if they are not viewed through a ‘trauma lens’ (Box 1). Filson explains the response of psychiatry:

‘I was essentially disconnected from any context that could have explained the chaos in and around me. This is what happens when the individual is viewed as the problem, rather than the world the individual lives in. When the actions we take to cope, or adapt, or survive are deprived of meaning, we look – well, crazy’ (Filson 2016: p. 21).

In shifting towards a model that assumes that service users might have experienced trauma and recognises that extreme behaviours may be adaptions to past traumas rather than symptoms of a mental illness, practitioners can better understand behaviours that enable a survivor to cope in the present moment. Often, extreme behaviours can best be understood as a survivor's best attempt at coping, connecting and communicating their pain (Filson Reference Filson2013) (Box 7).

BOX 7 Understanding extreme behaviours as coping, connecting and communicating

Many of the problematic trauma responses that a person has are often their best attempt at coping, connecting and communicating.

Coping Risk-taking or self-destructive behaviour (e.g. illicit substance use, extreme self-harm) can be an unconscious way of coping with internal suffering such as shame and low self-esteem and of managing emotional dysregulation and fight, flight or freeze (e.g. Baker Reference Baker, Shaw and Biley2013).

Connecting Rather than labelling service users who display difficult behaviour as ‘manipulative’ or ‘attention-seeking’, practitioners can attempt to understand the distress and fears that underlie particular ways of trying to get needs met and difficulties expressing them, and connect with the service user with empathy instead of judgement.

Communicating Research indicates that experiencing trauma in childhood has a major effect on neurodevelopment, making our threat responses extreme and easily triggered, compromising our ability to soothe ourselves and our integrative capacity (Van der Kolk Reference Van der Kolk2003). Distress of this kind is wired not to be easily managed via language. In addition, language has failed many survivors in stopping abuse, particularly where ‘No’ is ignored or violation continues. Consequently, extreme behaviours can be the only means a trauma survivor has to express or communicate the extreme distress they are experiencing.

(Based on Filson Reference Filson2013)

At times, aetiology is less important than the practitioner's response to the distress. Whether or not the practitioner sees it as a symptom of an underlying health condition (mental or physical: e.g. Barry Reference Barry, Hardiman and Healy2011) or even views the crisis as a choice, albeit a maladaptive choice, their response to it can either cause more distress and heighten alarm, or can support a lessening of distress and a return to emotional and physiological homeostasis. However, acknowledging underlying emotional and psychological pain and working with the person to develop insight and skills to manage, eliminate and even transform their distress necessitates a longer-term willingness to adopt a holistic model of mental distress that centralises the causal role of trauma and fully appreciates the range and severity of its impact. This entails a shift away from a biomedical understanding of mental health to a biopsychosocial model.

Universal expectation of trauma: moving beyond ‘power-over’ relationships

‘It is clear that there is no subset of traumatized people for whom we can build new structures, new institutions that will more adequately suit their needs. The world is a traumatized place’ (Bloom Reference Bloom2006: p. 58).

Blanch and colleagues have produced a guide to engaging women in trauma-informed peer support relationships (Blanch Reference Blanch, Filson and Penney2012). Many of the recommendations are applicable to all relationships in mental health services, including between men and women, service users and providers, between staff and within the National Health Service (NHS) as an organisation. They include:

• developing relationships that are non-judgemental, empathic, respectful and use honest and direct communication

• reflecting on racial or cultural biases and creating space for people to explore and define their cultural identity

• adopting a ‘gender lens’ in order to create safer environments and develop supports that are responsive to the needs and histories of women and men

• using the language of human experiences rather than clinical language to enable people to explore the totality of their lives

• moving beyond a helping role to mutuality and power-sharing.

On this latter point, they explain:

‘Being trauma-informed means recognizing some of the ways that “helping” may reinforce helplessness and shame, further eroding women's sense of self and their ability to direct their own lives. It means recognizing things you may be doing in your relationships that keep women in dependent roles, elicit anger and frustration, or bring on the survival responses of fight, flight, and/or freeze’ (Blanch Reference Blanch, Filson and Penney2012: p. 49).

Practitioners do not always have insight into, identify or appreciate the effects of the power dynamics within which they work and the culture that exists to fix or rescue people in paternalistic and disempowering ways. It is possible for practitioners to reflect on the working practices that characterise helping roles, which may not consider the service user's perspective, and attempt to move beyond them to work with people in more empowering ways. Box 8 outlines how the responses to Emma and Claire (Boxes 3 and 4) may have differed in trauma-informed services.

BOX 8 How Claire's and Emma's stories might have been different in trauma-informed services

Claire

On another ward where care plans are based on a formulation of the person in their context, it is understood that round-the-clock observation can cause long-term harm to a person's recovery. In this ward, another person called Claire still undergoes round-the-clock observation, but staff sit with this Claire to explain why and what their concerns are. Staff are as interactive as possible. They attempt to validate Claire's feelings of distress and engage in discussion about how to create a plan for ending observations with mutually agreed strategies. Partnering rather than enforcing is achieved. This Claire feels she has hope, because she is supported with the things that are important to her.

Emma

In another perinatal service where they operate a culture of trauma-informed care, Emma would have a person leading on her care, who sensitively asks about her experiences of trauma as routine, helps her make links between these experiences and her emotional distress and parenting problems, and also asks whether Emma feels safe from abuse. This professional links with Emma's health visitor to see what local or online peer support options there are. Emma realises that what she is feeling is common in her circumstances and feels connected enough with others to explore what she needs in order to develop her confidence as a mother.

On psychiatric in-patient wards this most obviously means addressing the retraumatisation that occurs through ‘power-over’ relationships that rely on physical or chemical restraints and seclusion to control people. Research has found that the use of physical restraint increases the risk of injury to staff as well as to service users, with the risk to service users including a risk of death (e.g. Mind 2013). Instead, practitioners can explore and develop alternative techniques such as de-escalation, advance directives and crisis planning, identification of risk factors, active listening and mediation (O'Hagan Reference O'Hagan, Divis and Long2008). A randomised controlled trial into the Safewards approach to reducing conflict and containment on psychiatric in-patient wards found that implementing simple interventions that improve relationships between staff and patients led to a reduction in the use of control and restraint (Bowers Reference Bowers, James and Quirk2015). Practitioners can reduce defensive behaviour, such as aggression, by considering what trauma-related triggers, including their own behaviour, might be contributing to the current situation. Responding to defensive behaviour openly and calmly, rather than mirroring the behaviour, can potentially diffuse the level of arousal through a process of co-regulation. Understanding, moderating and managing the fear/triggers driving aggressive responses is an essential component of trauma-informed practice.

Beyond the use of seclusion and restraint, ‘power-over’ relationships also manifest in subtle ways. Research suggests that service users' experiences of mental health services are characterised by powerlessness and formal and insidious coercion, which can lead to a fear of help-seeking and engagement (e.g. Norvoll Reference Norvoll and Pedersen2016). In becoming trauma-informed, practitioners can reflect on any paternalistic models of relating they may hold that can disable a person's autonomy and sense of self, that trigger flight, fight or freeze and subsequent coping mechanisms, and that disempower people from creating the support systems they need. Most simply, this can mean moving beyond interactions, or a lack thereof, that erode service users' basic sense of humanity. For instance, research into therapeutic alliances has found that service users are frequently ignored by in-patient staff leading to preventable frustration and anger (Sweeney Reference Sweeney, Fahmy and Nolan2014) (Box 9). This research further found:

‘Underpinning positive therapeutic alliances are the basic human qualities of staff and their ability to communicate these to service users. All service users valued relationships with staff who demonstrated kindness; warmth; empathy; honesty; trustworthiness; reassurance; friendliness; helpfulness; calmness; and humour’ (Sweeney Reference Sweeney, Fahmy and Nolan2014).

BOX 9 Subtle retraumatisation: dehumanising interactions on psychiatric wards

As a survivor researcher conducting research on psychiatric wards about therapeutic alliances, I (A.S.) witnessed the kinds of interaction service users were describing in their interviews.

A Black male approached the nurses station and stated that he hadn't had his medication. ‘You have’, stated the nurse. No eye contact, curt response, minimal engagement. ‘I haven't’. Pause. ‘I haven't, can you check?’. There was still no response. The man's clear frustration rose to anger. ‘Ask that nurse, she knows’. No response, no engagement. The man began shouting. ‘Don't talk to me like that. Keep shouting and we'll call the police’. The man carried on shouting, his anger increasing as his query remained unaddressed. A nurse moved out of the nurses' station and stood in front of the man. ‘Calm down or we'll call the police’. The man drew back his fist, verbally and physically threatening to punch her. Eventually he backed down, walked off, still visibly angry. His medication was still not checked.

See Sweeney Reference Sweeney, Fahmy and Nolan2014 for details of the study.

Service users in this study described forming better relationships with staff members who communicated their basic humanity to them and demonstrated basic levels of interest in and engagement with them. Forming relationships with service users that are rooted in these qualities can build trust, connection and hope, the foundation for positive relationships and trauma-informed practice. This can transform service user experience. Indeed, a body of therapeutic alliance literature suggests that therapeutic relationships between staff and service users create positive outcomes to the extent that they can be considered a form of therapy (e.g. Priebe Reference Priebe and McCabe2008). This is particularly important because experiencing trauma can have a huge impact on interpersonal relationships, whereas engaging in meaningful relationships can mediate the destructive impact of trauma (e.g. Van der Kolk Reference Van der Kolk2005). This suggests that staff should be supported, encouraged, recognised for and assessed on these qualities. Box 10 gives an account of Ted's experiences of staff responses to voice hearing which demonstrates the potential impact of staff fully engaging with service users and their experiences.

BOX 10 Case vignette: Ted

Ted has been admitted to psychiatric hospitals many times, hearing voices that threatened to hurt him. During his early admissions, staff told Ted that the voices were all in his head and that he had nothing to be afraid of. Although this was true, Ted did not find it soothing, but instead became more anxious as he felt he was not being listened to or believed. Ted worried that if these awful thoughts came from his own mind, then he must be either crazy or an evil person. Ted became more afraid of the contents of his mind. Recently, Ted's hospital has trained its staff in trauma-informed approaches and trauma responses. When Ted explains what he is experiencing, staff take the time to listen to him and explore his fears. Ted is asked what sense he makes out of hearing voices and about any previous times that he was able to manage the voices. Staff also ask whether Ted is aware of the Hearing Voices Network. In taking this approach, staff do not argue about reality, but acknowledge Ted's emotional distress and attend to it. This has the same purpose of letting Ted know that he is safe, but Ted experiences it as gentle and validating because he feels listened to. It also means that Ted has built strong relationships with many staff members and consequently feels well supported. Staff help Ted to understand that his reactions are common in people with his history and they find ways of helping him notice that the voices are triggered by particular social stresses. He is beginning to explore how these triggers link to his past.

There is also a clear need for greater transparency and trust and more focus on informed consent, with service users included in conversations about their support, in line with shared decision-making (e.g. Elwyn Reference Elwyn, Frosch and Thomson2012).

For practitioners interested in exploring further principles and techniques, Box 11 suggests a range of possible resources.

BOX 11 Suggested further resources for practitioners

Concluding thoughts

The specific actions that mental health practitioners can take in becoming trauma-informed may feel fuzzy, particularly beyond the obvious steps of reducing seclusion and restraint (Muskett Reference Muskett2014). This is because becoming trauma-informed does not mean ticking off a list of actions. Instead, trauma-informed approaches represent a shift in ideology and approach to service provision, with an attendant shift in ways of relating that can transform survivors' experiences of services and therapeutic relationships. This ideological shift is captured by the oft-quoted move from thinking ‘What's wrong with you?’ to considering ‘What happened to you?’. In introducing trauma-informed principles into practice, mental health staff attempt to: acknowledge the rates of trauma, including complex social and developmental traumas, among people who use mental health services; make sensitive enquiries about abuse and signpost people to appropriate support; ensure cultural and gender competence; adopt strengths-based models that see the service user as the expert in their own life and as having had the skills to survive; connect in ways that acknowledge the pain underlying extreme distress and behaviours; and recognise and address power imbalances that prevent mutuality, collaboration and choice, and consequently prevent survivors from engaging with services. As we have discussed, this has overlap with current NHS policy and other contemporary models of good practice, remembering that if trauma-informed principles are not adhered to, it is likely that trauma survivors will be unable to engage with services (Elliot Reference Elliot, Bjelajac and Fallot2005).

Trauma-informed approaches are clearly beginning to enter UK mental health practice (Sweeney Reference Sweeney, Clement and Filson2016). Beyond healthcare, they are also influencing UK homelessness services, children and family services, juvenile and adult criminal justice services, domestic violence services and more. One Small Thing, for example, is a charity that works with staff who engage with women in the criminal justice system to develop their trauma-informed practice (www.onesmallthing.org.uk/about/). The charity's name reflects the fact that the value of those small things – like compassion, understanding, respect - and their power to make a big difference (www.onesmallthing.org.uk/about/). This echoes our belief that lone practitioners can take big leaps towards becoming trauma-informed, even where they face cultural and organisational barriers.

Acknowledgements

The clinical vignettes included in this article were inspired by an exploration of people's experiences of iatrogenic harm in Tees, Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Foundation Trust as part of the organisation's Recovery Program. This work was conducted by the organisation's experts by experience in order to inform good clinical practice and the management of safety. A. S. would like to thank the Advisory Groups for their contribution to the APTT study (understanding and improving Assessment Processes for Talking Therapies), from which this article has arisen: Vanessa Anenden, Katie Bogart, Dr Sarah Carr, Dr Jocelyn Catty, Professor David Clark, Dr Sarah Clement, Alison Faulkner, Sarah Gibson, Mary Ion, Steve Keeble, Dr Angela Kennedy (co-author), Dr Gemma Kothari and Lana Samuels.

MCQs

Select the single best answer for each question.

1 Research has shown that experiencing childhood trauma can:

a affect mental well-being

b shorten life expectancy

c lead to worse outcomes in services

d a and b

e a, b and c.

2 In trauma-informed approaches, trauma is primarily understood as:

a a diagnosable medical condition

b having multiple causes, including social, historical and interpersonal

c a one-off life-threatening event that a person has witnessed or experienced

d recurrent symptoms that meet DSM-5 or ICD-10 criteria

e a disorder that meets the draft ICD-11 threshold for PTSD or complex PTSD.

3 Mental health services and systems can retraumatise survivors through:

a failing to ask about experiences of trauma and abuse

b failing to refer survivors to peer support

c failing to refer people to trauma-specific services

d failing to review the policies, procedures and practices that challenge people's sense of safety

e failing to employ trauma survivors as staff members.

4 Trauma-informed approaches primarily emerged in response to:

a practitioners’ dissatisfaction with mental health services and systems

b perceived failure of psychiatric systems to adequately diagnose and treat PTSD

c growing recognition that trauma is widespread and that it has enormous and wide-ranging effects on survivors

d US government guidelines supporting trauma-informed approaches

e psychotherapeutic work with trauma survivors.

5 Individual staff members working in trauma-uninformed organisations can:

a have little impact on people's lives because they face overwhelming organisational and cultural barriers

b experience high levels of toxic stress, which entirely prevent them from working in trauma-informed ways

c assume that very few of the service users they see will have experienced trauma

d partner with trauma survivors to co-deliver trauma-specific services

e work in trauma-informed ways with individual service users despite the barriers they face in doing so.

MCQ answers

1 e 2 b 3 d 4 c 5 e

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.