‘Life moves pretty fast. If you don't stop and look around once in a while, you could just miss it’

(Ferris Bueller's Day Off, 1986).There is broad agreement among addiction specialists that detoxification from most substances is relatively straightforward, but that maintaining abstinence is more problematic. A recent review of psychosocial treatments used in addiction services highlighted the low effect sizes seen in treatment outcomes and the minimal differences between these approaches (Reference LutyLuty 2015). It is well recognised, however, that individual therapist factors, such as empathy and the strength of the therapeutic relationship, can strongly influence outcomes (Reference Miller and MoyersMiller 2015). With this in mind, there is scope to refine our existing treatments and develop new approaches for those with addictive behaviour problems.

We will briefly outline trends in psychological treatments used in addictions, before describing mindfulness and its use in addictions. We then provide some practical information for interested clinicians on getting started.

Mindfulness and mindfulness-based approaches

Mindfulness-based approaches (MBAs) were first popularised in the West by Jon Kabat-Zinn, who integrated meditation practices into a mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) course for people experiencing a range of chronic health problems. He defined mindfulness as ‘paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally’ (Reference Kabat-ZinnKabat-Zinn 1994: p. 4). MBSR has been adapted by cognitive therapists as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) (Reference Segal, Williams and TeasdaleSegal 2013), which is a recommended treatment to prevent relapse in people who have experienced three or more episodes of depressive illness (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2009). MBSR, MBCT and mindfulness-based relapse prevention (MBRP) courses each consist of eight sessions, with a large overlap between the content of the different courses. The main topics of each session are summarised in Table 1. The major differences between MBSR and MBCT courses are summarised in Table 2. For a general introduction to mindfulness, see Reference MaceMace (2007).

TABLE 1 Comparison of 8-week programmes in mindfulness-based stress reduction, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based relapse prevention

TABLE 2 Comparison between mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction

Mindfulness courses (MBSR, MBCT and MBRP) are typically delivered by 2 teachers to a group of 12–18 participants. Each participant attends a pre-course interview to determine their suitability to take part. The course usually runs for 8 weeks, with the group meeting for a 2 h session every week. Each session includes a meditation skills practice, followed by an inquiry process in which participants are encouraged to describe their experience of the meditation; this is then explored with the teacher in the group setting. There is no requirement for participants to talk about their experiences during the inquiry process, and usually several people in a group choose not to do so. There are three main meditation skills in a traditional MBSR course: a ‘body scan’, ‘mindful movement’ and a ‘guided sitting practice’ (Box 1). Readers may be familiar with the introductory ‘raisin exercise’, which is often practised during taster sessions or short presentations on mindfulness. The meditative skills practised are of increasing complexity, and each one can relate to ways of experiencing sensations and difficulties participants may face, either during the meditation practice itself or in life. The course encourages participants to explore any emotional, cognitive and physical experiences which may occur during meditation and to be aware of what happens to these over time. Participants are required to practise skills daily between sessions and to record their experiences of this in a reflective diary. In the sessions themselves, learning can take place during the meditation, during the inquiry process with the teacher, or vicariously by listening to other participants’ descriptions of their own experiences.

BOX 1 Formal meditation practices in mindfulness-based stress reduction

Body scan

Lying on a mat and observing physical sensations in sequential parts of the body. Noticing whether there are any thoughts and feelings attached to these sensations, and how they change over time.

Mindful movement

Introducing movement to the body scan. Noticing particularly the physical sensations at the ‘edges’ of movements and any thoughts and feelings attached.

Guided sitting practice

Attaining a comfortable posture in a chair. Becoming aware of external sounds, the experience of breathing and physical sensations, and noticing thoughts and feelings as they arise.

There is no formal definition of MBAs, but they are generally considered to include MBSR, MBCT and MBRP courses, as well as the teaching and use of mindfulness skills outside such courses (either in individual therapy sessions or as part of another psychotherapy). Mindfulness courses themselves continue to develop, and compassion practice has now been introduced into 8-week MBSR and MBCT courses. ‘Loving kindness’ and ‘nurturing compassion’ are seen as essential components of MBAs; many would consider compassion practice to be the key that unlocks the potential of mindfulness. Individuals presenting to statutory addiction services with addictive behaviour problems often describe experiencing suffering and a background of trauma. This makes it key for them to learn about nurturing compassion towards themselves. Reference ThakurThe Royal College of Psychiatrists (2015) has recently published a document highlighting the importance of compassion and the value of mindfulness as an aid to developing compassion.

Trends in psychological interventions in addictions

Three ‘waves’ of therapies have influenced psychological treatments over the past 50 years. The first wave, behavioural therapies, included punitive measures such as electrical aversion treatments to reduce cravings in alcohol dependence. The second wave, cognitive–behavioural therapies (CBT), were specifically adapted for addictions (Reference Beck and EmeryBeck 1977) and led to an influential model of relapse prevention that focused on how an individual responds in high-risk situations (Reference Marlatt and GordonMarlatt 1985). Individuals learn alternative coping strategies to manage the difficulties experienced when facing high-risk situations. Relapses are no longer seen as failures, but as opportunities to understand behaviour, identify associated factors and develop new coping skills. Relapse prevention remains one of the most commonly used approaches in addiction services (Reference Wanigaratne, Davis and PryceWanigaratne 2005).

Third-wave therapies, which are often referred to as contextual CBT as they adopt a more contextualised approach than traditional CBT, have been developed over the past 20 years. Many of these include MBAs (Reference HayesHayes 2004) (Box 2). Contextual CBT differs from traditional CBT in several ways. For example, there is no goal to change negative thoughts or feelings. Instead, the aim is to help a person to recognise and alter their relationship with their thoughts and feelings, by impartially and compassionately observing these with an open curiosity. MBAs are often ‘transdiagnostic’, in that they are considered to be suitable for different and multiple problems, rather than a single disorder. They are also likely to be delivered in group settings. Perhaps the major difference between conventional CBT and the contextual approach is that contextual CBT therapists have not only completed a formal course and a teacher training programme, but continue to maintain their own personal practice of the therapy.

BOX 2 Examples of third-wave therapies that include specific mindfulness skills

Therapy

-

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT)

-

Compassion-focused therapy (CFT)

-

Dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT)

-

Metacognitive therapy (MCT)

-

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT)

-

Mindfulness-based relapse prevention (MBRP)

-

Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR)

Developer/s

-

Steven Hayes

-

Paul Gilbert

-

Marsha Linehan

-

Adrian Wells

-

Zindel Segal, Mark Williams and John Teasdale

-

Alan Marlatt and Sarah Bowen

-

Jon Kabat-Zinn

Mindfulness-based approaches in the treatment of addiction

Strategies to reduce stress are seen as a useful approach in addictions, as the biological link between addiction and stress has long been recognised (Reference SinhaSinha 2007; Reference DudleyDudley 2014). In the 1970s, studies found meditation to be helpful to those with addictive behaviour problems (Reference Benson and WallaceBenson 1971; Reference Shafi, Lavely and JaffeShafii 1974, Reference Shafi, Lavely and Jaffe1975). In the 1980s, meditation was also considered to be a useful coping strategy in relapse prevention to reduce stress and negative affect, and to encourage mindfulness (Reference Marlatt and GordonMarlatt 1985). This can then strengthen self-efficacy – the belief that one can successfully perform a behaviour required to produce a particular outcome (Reference BanduraBandura 1977) – and the possibility of relapse is therefore reduced. Reference Kadden and LittKadden (2011) reviewed the role of self-efficacy in those with addictive behavioural disorders and found it to be an important predictor of outcome or a mediator of treatment effect. Introducing MBAs could potentially improve outcomes by reducing stress and increasing self-efficacy.

Reference MarlattMarlatt (2002) was initially sceptical about meditation. However, he agreed to a trial at the suggestion of his physician and – after finding it helpful in reducing his own blood pressure – thought it might be a helpful coping skill to promote relaxation in those with addictive behaviours. MBAs have subsequently been integrated into many traditional relapse prevention programmes, and Sarah Bowen, Neha Chawala and Alan Marlatt have developed a clinician's guide to MBRP (Reference Bowen, Chawla and MarlattBowen 2011). A systematic review (Reference Zgierska, Rabago and ChawlaZgierska 2009) and more recent randomised controlled trials (Reference Bowen, Witkiewitz and ClisaefBowen 2014a; Reference Witkiewitz and BowenWitkiewitz 2010, Reference Witkiewitz, Warner and Sully2014a) have all supported the effectiveness of MBAs in addictions.

Reference Zgierska, Rabago and ChawlaZgierska et al (2009) considered the existing evidence on a range of mindfulness meditation-based interventions for substance use disorders. They considered 25 articles and concluded that preliminary evidence suggested that mindfulness meditation was efficacious and safe. Many studies had methodological limitations, and the review provided guidance for those conducting further research in MBAs. Reference Witkiewitz and BowenWitkiewitz & Bowen (2010) found MBRP to be a superior treatment when compared with a 12-step approach, although the strength of this finding was limited as the follow-up period was only 4 months. In a further randomised controlled trial comparing MBRP with relapse prevention at a residential addiction treatment facility for female offenders, individuals in the MBRP group reported significantly fewer drug use days and fewer legal and medical problems, but the follow-up period was only 15 weeks (Reference Witkiewitz, Warner and SullyWitkiewitz 2014a).

Reference Bowen, Witkiewitz and ClisaefBowen et al (2014a) looked at 286 patients who had successfully completed either 28 days of inpatient or 90 days of out-patient treatment for a substance use disorder. They were predominantly unemployed males in their 30s or 40s who used several drugs, with or without alcohol. Patients were randomly allocated to one of three groups running for 12 months. Two groups received a 12-month structured relapse prevention programme, which included either an 8-week MBRP course or an 8-week CBT-based relapse prevention programme. The third group received treatment as usual, which was participation in an abstinence-based 12-step group. The main findings were that at 6-month follow-up significant differences had emerged between the relapse prevention groups and the treatment-as-usual group; with relapse prevention, fewer patients over the previous 3 months had used drugs or drunk heavily, and those who had drunk heavily had done so on a third fewer days. At 12-month follow-up, the MBRP group was consistently performing better than the CBT-based relapse prevention or treatment-as-usual groups; these advantages included statistically significant differences with respect to heavy drinking and days of drug use. However, answers to many questions remain uncertain, including which MBAs should be offered, to whom, by whom and for how long; as well as how MBAs work and what the best implementation strategies are (Reference Witkiewitz and BlackWitkiewitz 2014b).

The essence of mindfulness in addictions is to ‘raise awareness of specific triggers and the “automatic” responses that often follow, to recognise early warning signs for relapse, and to increase an ability to be with the discomfort of substance misuse’ (Reference Bowen, Witkiewitz, Chawla, Hayes and LevinBowen 2012: pp. 107–108). However, it is clear that for some individuals, traditional relapse prevention treatments without a specific mindfulness component may be sufficient to achieve this. Perhaps, then, the individuals who benefit from MBAs are those who would not otherwise recognise or experience their thoughts, feelings and physical sensations in high-risk situations: meditation helps them to become more aware of these experiences, while the inquiry process helps develop a vocabulary to describe them. Research supporting this hypothesis includes a study which found an inverse correlation between students’ dispositional mindfulness (an individual trait or disposition towards being mindful, which can be developed through meditation practice) and the quantity and frequency of their alcohol and cannabis consumption (Reference PhilipPhilip 2010). This finding has been replicated clinically (Reference Bowen and EnkemaBowen 2014b). Low dispositional mindfulness is also associated with individuals who self-medicate with prescription opioids (Reference Garland, Hanley and ThomasGarland 2015).

Practical information on getting started

Clinicians interested in mindfulness should first consider experiencing an MBA course. They can then decide whether to complete further training to deliver MBA courses themselves, or whether they prefer to find teachers from elsewhere to introduce MBAs to the service in which they work. There is clear guidance concerning good practice in teaching MBA courses in the UK (UK Network for Mindfulness-Based Teacher Trainers 2011). There is an MBRP teacher training course delivered by Action on Addiction, an organisation affiliated with the UK Network for Mindfulness-Based Teacher Training Organisations. It is unclear how teachers of a particular MBA can cross over to teach another MBA. For example, an MBSR teacher would perhaps require training in cognitive therapy or relapse prevention to teach MBCT or MBRP, respectively, whereas an MBCT teacher would require training in mindful movement to teach MBSR.

Cost considerations, funding and working with other stakeholders

Approaches in treating addictive behaviours are cyclical and may often be influenced as much by political factors as by the evidence base for particular interventions (Reference LutyLuty 2014). Introducing new interventions within an addiction service usually requires the approval of those who manage and commission services, particularly if additional funding is required. In the UK, many addiction services are now delivered outside the National Health Service (NHS) by non-statutory or third-sector organisations. It may be possible to influence the development of MBAs elsewhere, particularly within third-sector organisations which value the experience and support of addiction specialists. Indeed, several of these organisations already offer various forms of MBAs, and it can be useful for clinicians to develop expertise in this area so that they can either assist in the running of groups or provide non-clinical support, such as supervision or governance strategies, as needed.

It may be possible to offer MBAs within existing resources, as they can be extremely cost-effective. First, they are delivered to groups rather than individuals. Second, there is potential to deliver MBAs in local community settings, rather than in hospitals, where space tends to be more costly and more difficult to obtain. Third, because MBAs may be transdiagnostic, and many people experiencing a chronic illness have multiple morbidities (Reference Barnett, Mercer and NorburyBarnett 2012), it may be possible to adapt an MBA course to cover other symptoms such as anxiety, depression or chronic pain. This approach also helps if participant numbers are low, for example in remote or rural areas, where an open or mixed course may be more viable. This can be facilitated by liaison with other specialties. Costs may include start-up funding for teacher training, as well as ongoing development needs. Equipment needs are relatively small.

Initially, running a pilot course may be all that can be agreed upon or secured financially, but planning for a continuing series of courses is recommended. Ideally, there will be opportunities for participants to move into practice groups after completing the MBA course; this becomes easier as numbers grow. This is an ideal opportunity for previous participants to contribute (Box 3) and to involve third-sector organisations and community groups.

BOX 3 Case vignette: a participant

Ms A, a 36-year-old woman with a longstanding history of alcohol dependence, was referred to the addictions service for relapse prevention work following a community detoxification prescribed by her general practitioner. There was a history of episodes of low mood and self-harm since she was a teenager. She currently had symptoms of social phobia and depression. She was long-term unemployed and her marriage had broken down secondary to her alcohol use. She was socially isolated and was expressing suicidal ideation. She was motivated to maintain abstinent but was at high risk of relapse.

Ms A was referred to an anxiety management group. She attended and gained some benefit, but remained socially avoidant. She then attended the team clinical psychologist for individual cognitive– behavioural therapy work with some additional benefit, but she continued to struggle with anxiety and social avoidance. The clinical psychologist introduced some mindfulness and compassion-focused work to their sessions and referred Ms A to an 8-week mindfulness-based relapse prevention group.

Ms A became very interested in mindfulness approaches; she attended the group regularly throughout the course and embraced the personal mindfulness practice. She incorporated mindfulness practice into her daily routines and has continued to practise regularly since. She is now regularly attending Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, a recovery café and other community-based groups. She is volunteering as a peer support worker and has remained abstinent. She believes mindfulness helps her to manage her anxiety better, to slow down her breathing and to control her emotions when feeling stressed or experiencing cravings for alcohol.

Teachers

Teachers of MBA courses can be employed independently or through third-sector organisations, or they may be members of community addiction teams. If teachers delivering a course also have responsibility for treatments such as prescribing take-away opioid replacement therapies or benzodiazepines, it is worth considering how this may affect both the therapeutic relationship and the course experience. Individuals with previous addictive behaviour problems who take on new social roles – for example, as meditators – can benefit both themselves (Reference WestWest 1979) and course participants, as they will have their own authentic experiences of mindfulness in high-risk situations.

Participants

The MBRP clinician's guide (Reference Bowen, Chawla and MarlattBowen 2011) suggests that the course is intended for people who have competed initial treatment for addictive behaviour problems. For example, in the study described earlier, the authors chose to recruit participants who had successfully completed either 1 month of intensive in-patient treatment or 3 months of out-patient treatment (Reference Bowen, Witkiewitz and ClisaefBowen 2014a).

Teaching MBAs to individuals who are not abstinent, or who continue to use substances in harmful or dependent ways, is of uncertain benefit. However, if individuals who continue to use substances are excluded, then one needs to consider the suitability of individuals prescribed opioid replacement therapies (methadone, buprenorphine or injectable opioid treatments). Methadone can blunt emotional reactivity (Reference Savvas, Somogyi and WhiteSavvas 2011), and so individuals prescribed methadone at high doses may find it difficult to experience their feelings as easily during mindfulness skills practice than those prescribed lower doses. However, in a study of methadone-maintained parents, those who received a parenting intervention which included mindfulness skills showed significant reductions in problems across multiple domains of family functioning, in addition to a lowered methadone dose (Reference Dawe and HarnettDawe 2007). This intervention has been found to be cost-effective (Reference Dalziel, Dawe and HamettDalziel 2015).

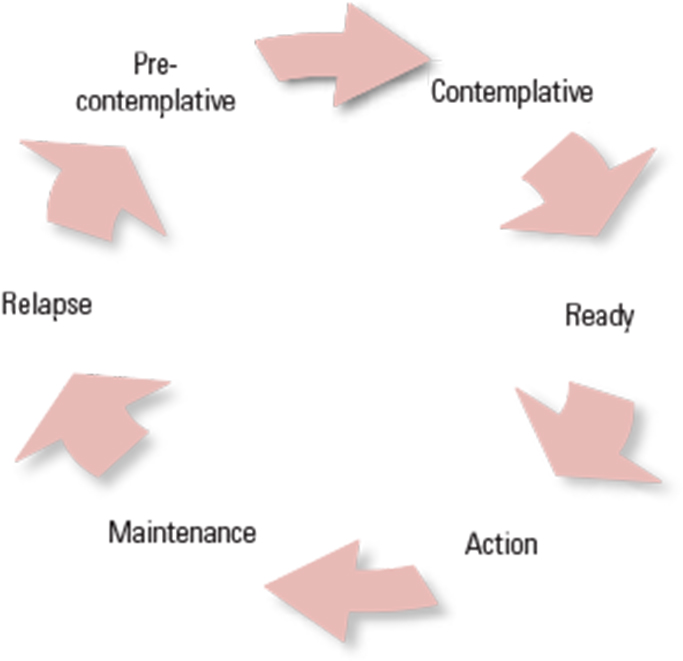

The transtheoretical model of behavioural change (Fig. 1) measures the readiness of an individual to change an addictive behaviour (Reference Prochaska, DiClemente and NorcrossProchaska 1992). The model has been highly influential in determining when specific addictions treatments are likely to be most effective. For example, if a person is in the contemplative stage of the model, weighing up the pros and cons of changing an addictive behaviour can lead to a profound ambivalence about change and at this stage motivational interviewing is appropriate. However, if a person is ready to change, then motivational interviewing may have a negative effect and other psychosocial treatments are more appropriate (Reference Miller and RollnickMiller 2013). Similarly, if an abstinent individual in treatment returns to feeling ambivalent about remaining abstinent, then continuing with the same psychological treatment can be detrimental. The ability to recognise this change in motivation is therefore essential. MBAs can be advantageous in this situation, as they teach the individual to observe and notice their own experience of reduced motivation.

FIG 1 The transtheoretical model of behaviour change (after Reference Prochaska, DiClemente and NorcrossProchaska et al, 1992).

Given that there is little evidence to suggest who to include in an MBA course, a reasonable approach may be to have as few inclusion and exclusion criteria as possible, and to offer courses to interested people attending addiction services, subject to a pre-class interview. This interview is widely considered to be key to engagement and establishing a personal connection, and although there is little published research to support this, chapter 6 of the standard MBCT text is devoted to it (Reference Segal, Williams and TeasdaleSegal 2013). It may be that an MBA course is not suitable for some individuals, owing to personal circumstances or current mental health problems. We do not think that abstinence should be a strict inclusion criterion, but would ask participants to respect a few ground rules, including not attending while intoxicated or in acute withdrawal, as this would be disruptive. Reference ArrienArrien's (1993) four rules for life offer good advice:

‘Show up and be present. Pay attention to what has heart and meaning. Tell the truth without blame and judgement. Be open to (but not attached to) outcome.’

Spiritual issues

MBAs are considered to originate from Buddhist traditions, dating back over 2000 years, and it has been suggested that aspects of Buddhist philosophy may be pertinent to theories of the cause and treatment of addictive behaviour problems (Reference Groves and FarmerGroves 1994; Reference MarlattMarlatt 2002). MBAs are also similar to contemplative practices in major faith religions and have been adapted as treatments in secular or non-religious settings to make them more accessible and acceptable to people from diverse backgrounds (Cook 2015; Reference WestWest 1979). There are differing views on how the boundary between the secular and the religious should be managed in clinical practice (Cook 2015). It is essential that professionals and organisations who deliver MBAs follow relevant guidance (Reference CookCook 2013; General Medical Council 2013).

Audit and research

There have been few UK-based MBRP studies, and further evidence is required to fully assess the effectiveness of MBAs in addictions and how they are best delivered. As with any practice, consider auditing courses and perhaps offer to contribute to further research. Within the addictions field, abstinence has long been the outcome measure favoured by politicians, the media and senior managers within the NHS. However, in keeping with the spirit of MBAs, it seems sensible not to make the aim striving for abstinence, but rather to look at the experiences of people who have completed courses.

Conclusions

MBAs warrant consideration by those commissioning and delivering services for individuals with addictive behaviour problems. MBAs are cost-effective and likely to benefit the increasing number of individuals with multiple chronic morbidities. A randomised controlled trial comparing MBRP with CBT-based relapse prevention over 1 year found MBRP to be the more efficacious treatment (Reference Bowen, Witkiewitz and ClisaefBowen 2014a). Further research is required; however, the importance of individual therapist factors suggests that it may be worthwhile focusing on the selection and training of teachers. Mindfulness practices are also useful for health professionals (Box 4): they can nurture compassion and the feeling of a strong desire to alleviate the suffering of others, which can enrich our work and reduce burnout:

‘spread this wisdom and perhaps train us in following a new and mutually beneficial path’ (Reference ThakurThakur 2015: p. 193).

BOX 4 Case vignette: a teacher

Dr P was an addiction psychiatrist who had completed formal training in cognitive–behavioural therapy and had an interest in mindfulness. He completed an 8-week mindfulness-based approaches (MBA) course which he found interesting, and he could see that this approach might be useful. He then completed an MBA teacher training programme over 12 months, which included a residential 3-day retreat towards the end of the programme.

Dr P found the practice of some of the meditation techniques during the retreat challenging. For example, he experienced lower back pain during some of the lengthier sitting practices on the final day; however, he found the application of mindfulness techniques very useful in this situation. He found that through focusing his attention on the pain rather than trying to ‘block it out’, together with a compassion practice directed towards himself, his experience of pain was altered. He believes this experience has improved his ability as a teacher, as he is aware through his own personal practice that the application of meditation skills may lead to changes in physical sensations. This, alongside his regular practice, adds to the authenticity of the approach.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Who of the following has been the least influential in the development and integration of mindfulness skills in addictions?

-

a Alan Marlatt

-

b Aaron Beck

-

c Kate Witkiewitz

-

d Sarah Bowen

-

e Neha Chawla.

-

-

2 Which of the following is not a recognised mindfulness skill?

-

a Sitting practice

-

b The body scan

-

c Mindful movement

-

d Breath-holding

-

e The raisin exercise.

-

-

3 Which of the following therapies does not include mindfulness skills?

-

a Dialectical behaviour therapy

-

b Formal cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT)

-

c Compassion-focused therapy

-

d Acceptance and commitment therapy

-

e Metacognitive therapy.

-

-

4 Which of the following statements is true?

-

a There are no randomised controlled trials supporting the value of mindfulness-based approaches (MBAs) in addictions.

-

b There are no systematic reviews supporting the value of MBAs in addictions.

-

c A recent study found no difference between the mindfulness-based and CBT-based relapse prevention groups at 12-month follow-up.

-

d There is uncertainty about which individuals with addictive behavioural problems will benefit from MBAs.

-

e There are clear guidelines concerning who is best suited to teach MBAs to those with addictive behaviour problems.

-

-

5 Which of the following statements is false?

-

a MBAs are cost-effective.

-

b MBAs are can be helpful for those working within an addictions service.

-

c MBAs are derived from Buddhist traditions.

-

d There is guidance on the teaching of MBAs in UK settings.

-

e Relapse prevention was developed from MBAs.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | b | 2 | d | 3 | b | 4 | d | 5 | e |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.