The Faculty of the Psychiatry of Old Age of the Royal College of Psychiatrists has reaffirmed that ‘specialist old age services are best equipped to diagnose and treat mental illness in an ageing population’ and supports the principle that older people have access to dedicated and specialist old age services for functional illnesses and dementia (Faculty of the Psychiatry of Old Age 2015: p. Reference Abdul-Hamid, Lewis-Cole and Holloway1). Its report, developed after extensive consultation with various stakeholders, recommends new needs-based criteria as an alternative to age as a criterion for accessing old age services. These criteria are set out in Box 1.

BOX 1 Needs-based criteria for accessing old age psychiatric services

• Primary dementia, regardless of the person's age

• Mental disorder and physical illness or frailty that contributes to, or complicates the management of, the person's mental illness, regardless of their age

• Psychological or social difficulties related to the ageing process, or end-of-life issues, or the person's opinion that their needs may be best met by a service for older people; this would normally include people over 70 years of age

(Faculty of the Psychiatry of Old Age 2015)

In the UK, a number of factors appear to have contributed to a move to integrate old age services with those of working-age adults, including changes in healthcare commissioning, the economic downturn since 2008, the cost pressures faced by the National Health Service (NHS), the austerity drive aiming for greater efficiency, and innovative use of available resources to meet the complex physical, psychological and social needs of the mentally ill (Anderson Reference Anderson, Connelly and Meier2013; Warner Reference Warner2014, Reference Warner2015). With a growing older population there has also been an associated increase in the incidence of dementia. However, the single most important driver is perhaps the introduction of Equality Act 2010, which governs the whole of the UK.

The Equality Act, which made any unjustified discrimination in provision of services on the grounds of chronological age unlawful, demanded that the parity of esteem, equitability in allocation of resources and improved access to services that were already available to working-age adults (aged 16–64 years) also be made available to older adults (aged 65 and over). The World Psychiatric Association had recently noted that combating ageism was part of the remit of services for older people (Katona Reference Katona, Chiu and Adelman2009). However, given the funding and resource challenges faced by the NHS in general, and mental health services in particular, this might have been an opportune moment to consider an ‘age-inclusive’ or ‘all-age’ service as the best way to ensure that service provision falls on the right side of the legal framework. However, concerns have been raised by various stakeholders that the rather hasty implementation of age-inclusive services that were not designed to meet the specific needs of older adults may inadvertently have caused more discrimination. Anderson et al (Reference Anderson, Connelly and Meier2013) noted that inequality was more likely to be reported when older people were seen by a single age-inclusive service. A national survey of service provision in 2012 found that at least 60% of respondents (NHS healthcare providers) reported that ‘ageless’ services resulted in deterioration in such important domains as access to services, continuity of care, services meeting patients’ needs and person-centred care, as well as an increase in inappropriate referrals, missed diagnosis, patients ‘falling through the gaps’ and caregiver distress (Warner Reference Warner2014).

This is happening against a background of existing discrimination and inequality created by the differential implementation of health policy and the National Service Frameworks (NSFs) for England (Anderson Reference Anderson, Connelly and Meier2013). For example, the NSF for Older People addresses only dementia and depression – older people with other mental health problems are treated in accordance with the NSF for Mental Health, which covers general adult psychiatry. Older people, in the main, have been denied access to some services (assertive outreach, crisis resolution home treatment and early intervention) available to younger adults, and services that were developed as specialties of general psychiatry, such as hospital liaison, rehabilitation, psychotherapy and addictions, often exclude people over 65 (Anderson Reference Anderson, Banerjee and Barker2009). Despite evidence that shows the effectiveness of services for older people and their potential to deliver better care and value for money, very little effort has been made to develop such services, thus missing a vital opportunity to improve clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness (Anderson Reference Anderson, Banerjee and Barker2009).

Although times have changed and legislation has has progressed, negative attitudes towards old age still persist. Furthermore, as Anderson et al (Reference Anderson, Connelly and Meier2013) noted, ‘Governments and commissioners have shown a surprising failure to realise the significance of the ageing population, adopt best practice and make service development for older people a national priority’. All this has reopened the debate on the interface between general adult and old age psychiatry. At this juncture it would be helpful to consider how the specialty of old age psychiatry has evolved.

History of old age psychiatry

Hilton's comprehensive review of the history of old age psychiatry (Hilton Reference Hilton2015) shows that, before the 1950s, dedicated old age services were almost non-existent. The stereotypical view of the inevitability of decline with older age undermined proactive approaches to treatment. Psychiatrists working across all ages offered little to older people. Ronald (Sam) Robinson established the UK's first documented dedicated comprehensive old age psychiatric service at Crichton Royal Hospital in Scotland in 1958.

Services for older people have continued to lag behind those for younger people (Anderson Reference Anderson, Connelly and Meier2013; Hilton Reference Hilton2015). Since the 1970s, policies for older people have appeared after those for younger people, reinforcing the idea that the needs of older people are less pressing. For example, The NSF for Mental Health (for working-age patients) came 2 years earlier than the NSF for Older People (Department of Health 2001).

Hilton found that there were few formal studies comparing the clinical effectiveness of dedicated old age and all-age psychiatric services (Hilton Reference Hilton2015). One study, conducted in 1985–1986, that compared ‘specialised’ and ‘non-specialised’ services treating older people with mental illness indicated outcomes ‘in favour of the specialised services’ (Wattis Reference Wattis1989), suggesting that dedicated services provided more forward-thinking and needs-led care. In a more recent study, elderly patients with long-term mental illnesses in contact with old age psychiatry had significantly fewer unmet needs compared with those in contact with general adult psychiatry (Abdul-Hamid Reference Abdul-Hamid, Lewis-Cole and Holloway2015).

The interface between general adult and old age psychiatry

The specialty of old age psychiatry looks after patients who are frail and vulnerable. In addition to patients of any age who have dementia, the specialty manages older patients with functional psychiatric disorders, physical illness and frailty and those with psychological and social difficulties associated with old age (Pomerleau Reference Pomerleau and McKee2005). As mentioned earlier, needs-led criteria for accessing old age services have been suggested (Box 1), but understanding of four areas in particular is important to their successful implementation – as well as to ensuring that these services eliminate ageism, while preserving the ‘specialism’ and benefits of dedicated old age psychiatric services:

• the definition of ‘old age’

• the commonly encountered problems in old age psychiatry

• frailty and physical illness

• the procedures for transfer of patients between adult and old age services.

What does ‘old age’ mean?

The meaning of ‘old age’ is constantly evolving as life expectancy increases and the culture of ageing and identity of older people change (Sanderson Reference Sanderson and Scherbov2008; Carstensen Reference Carstensen and Fried2012; Harper Reference Harper2013). Currently in most Western societies the chronological age of 65 and over, when degenerative changes of ageing become noticeable and retirement is a social norm, is accepted as a definition of older person (Akman Reference Akman2000). The UK's Guidance for Commissioners of Older People ' s Mental Health Services (Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health 2013) mainly focuses on people aged 65 and over. The same age is accepted for commonly used indicators of ageing in demographics (Sanderson Reference Sanderson and Scherbov2008). However, this definition is arbitrary as there is a great variability in the health and level of functioning of people over 65 (Carstensen Reference Carstensen and Fried2012). It is expected that the period of old age associated with frailty and dependence will shift from the current mid-70s into the mid-80s, and that the transitional period after midlife and before frailty will shift from 60–75 to 70–85 by around 2025 (Harper Reference Harper2013). Recognising these changes and variabilities is important from a social perspective in developing age-based services, policies and programmes (Carstensen Reference Carstensen and Fried2012).

Commonly encountered problems in old age psychiatry

Depression

Depressive disorder is the most frequent psychiatric illness in older people, a leading cause of suicide and an independent predictor of mortality (Baldwin Reference Baldwin and Wild2004). The overall prevalence of major depression in older people is estimated at 2% and the prevalence of clinically significant depressive symptoms is between 10 and 30%, with higher rates in clinical and nursing home settings (Variend Reference Variend and Gopal2008). Depression can complicate stroke, Parkinson's disease and dementia. High rates of depressive symptoms are also observed in a range of chronic medical disorders, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart disease (Baldwin Reference Baldwin and Wild2004).

Clinically, depression in older people commonly presents with symptoms of psychomotor change, anhedonia, cognitive impairment and weight loss. It may also present with fewer reported symptoms of dysphoria, but with more anxiety and somatic complaints of unexplained medical aetiology, than are seen in younger people (Hegeman Reference Hegeman, Kok and van der Mast2012). There is a poorer treatment outcome and a greater incidence of completed suicide (Baldwin Reference Baldwin and Wild2004; Variend Reference Variend and Gopal2008).

There is a positive and potentially bidirectional association between depressive symptoms and frailty status in older people. Depression in later life is predictive of many of the same kinds of outcome as frailty, including disability and mortality (Mezuk Reference Mezuk, Edwards and Lohman2012). There is a strong association between late-life depression and cognitive impairment (Edo Reference Edo, Reitz and Honig2013). Depressive symptoms occur in 40–50% and major depression in 10–20% of people with Alzheimer's disease (Wragg Reference Wragg and Jeste1989). Depressive symptoms were observed in 3–63% of older adults with mild cognitive impairment in population-based studies (Panza Reference Panza, Frisardi and Capurso2010). The causal relationship between late-life depression and cognitive impairment is complex and remains to be elucidated. Depression may increase the risk of cognitive decline and dementia, especially Alzheimer's disease, via multiple pathways (Butters Reference Butters, Young and Lopez2008). There is evidence that depression accompanies cognitive impairment but does not precede it (Edo Reference Edo, Reitz and Honig2013).

Depression in older people is not well recognised and is often not optimally managed. There is a difficulty in diagnosing depression in the context of the comorbid medical conditions and cognitive impairment that are common in later life. Depression is often obscured by physical and cognitive decline (Variend Reference Variend and Gopal2008). Increased risk of organic conditions contributing to depression makes assessing depression and planning investigations in older people a special skill (Baldwin Reference Baldwin and Wild2004). Old age psychiatrists have additional training and expertise in the diagnosis and management of physical and psychiatric comorbidity.

Early-onset dementia

Early-onset dementia (onset before 65 years of age) is increasingly recognised because of its clinical significance and social importance. Its prevalence is probably underestimated (Jefferies Reference Jefferies and Agrawal2009) and those with the disease form a heterogeneous group that is poorly understood. As a result, early-onset dementia is likely to be underdiagnosed and inadequately treated, with limited services and resources (Vieira Reference Vieira, Caixeta and Machado2013).

Early-onset dementia affects people who are still in active employment, providing for families and caring for children (McMurtray Reference McMurtray, Clark and Christine2006; Jefferies Reference Jefferies and Agrawal2009). Patients are more likely than the general population in the same age range to feel distressed and frustrated, and depression occurs frequently. Care is complex: it requires input from a multidisciplinary team and benefits from the support offered by voluntary organisations (Jefferies Reference Jefferies and Agrawal2009). Spouses of patients with early-onset dementia often experience financial problems and a feeling of lack of support and social isolation (Kaiser Reference Kaiser and Panegyres2006).

There are not enough services for early-onset dementia, provision of specialist services remains patchy, and carers and patients can be stuck between psychiatry and neurology. There is a need in the UK for specialist services for patients with early-onset dementia and their carers (Jefferies Reference Jefferies and Agrawal2009), and they should sit within old age psychiatric services. Dedicated early-onset dementia services within old age services could be set up by using a ‘hub-and-spoke’ model. This has been adopted in behavioural neurology and neuropsychiatry (Jethwa Reference Jethwa, Joseph and Khosla2016) and it involves the concentration of expertise in regional ‘hubs’ with outreach clinics, ‘spokes’, to support services away from regional centres. Case conferences and written and telephone advice can foster effective case management.

End-stage dementia

Patients with advanced dementia experience significant comorbidities, including dehydration and malnutrition. Care is often multidisciplinary, involving physicians, old age psychiatrists, liaison psychiatrists and other allied health professionals. Old age psychiatrists are strategically placed to coordinate the care of patients with complex physical and psychiatric comorbidity. Advance care planning (ACP) is a targeted intervention that promotes autonomy for end-of-life decisions before decision-making capacity is lost. A recent review of this area identified three core themes: barriers to ACP (patient- and professional-specific), raising awareness and fostering communication between families and healthcare professionals, and the management of issues specific to end-stage dementia (Jethwa Reference Jethwa and Onalaja2015).

Patient and professional education, early in the course of dementia, is important to promote patient autonomy and prepare patients and families. In addition, old age psychiatry and medicine can complement each other by identifying and managing the many causes of behavioural disturbance in dementia. Dementia special care units or ‘medical mental health units’ pool expertise to ensure that patients receive tailored holistic care. At present, these services are centred in a small number of specialised units. Better communication, greater patient comfort and carer satisfaction were noted in a retrospective cross-sectional study of 13 nursing homes with specialised dementia units in Boston, USA (Engel Reference Engel, Kiely and Mitchell2006). There is a scope for further research to assess outcomes and service development opportunities, including developing a hub-and-spoke model of services.

Frailty: the conceptual framework

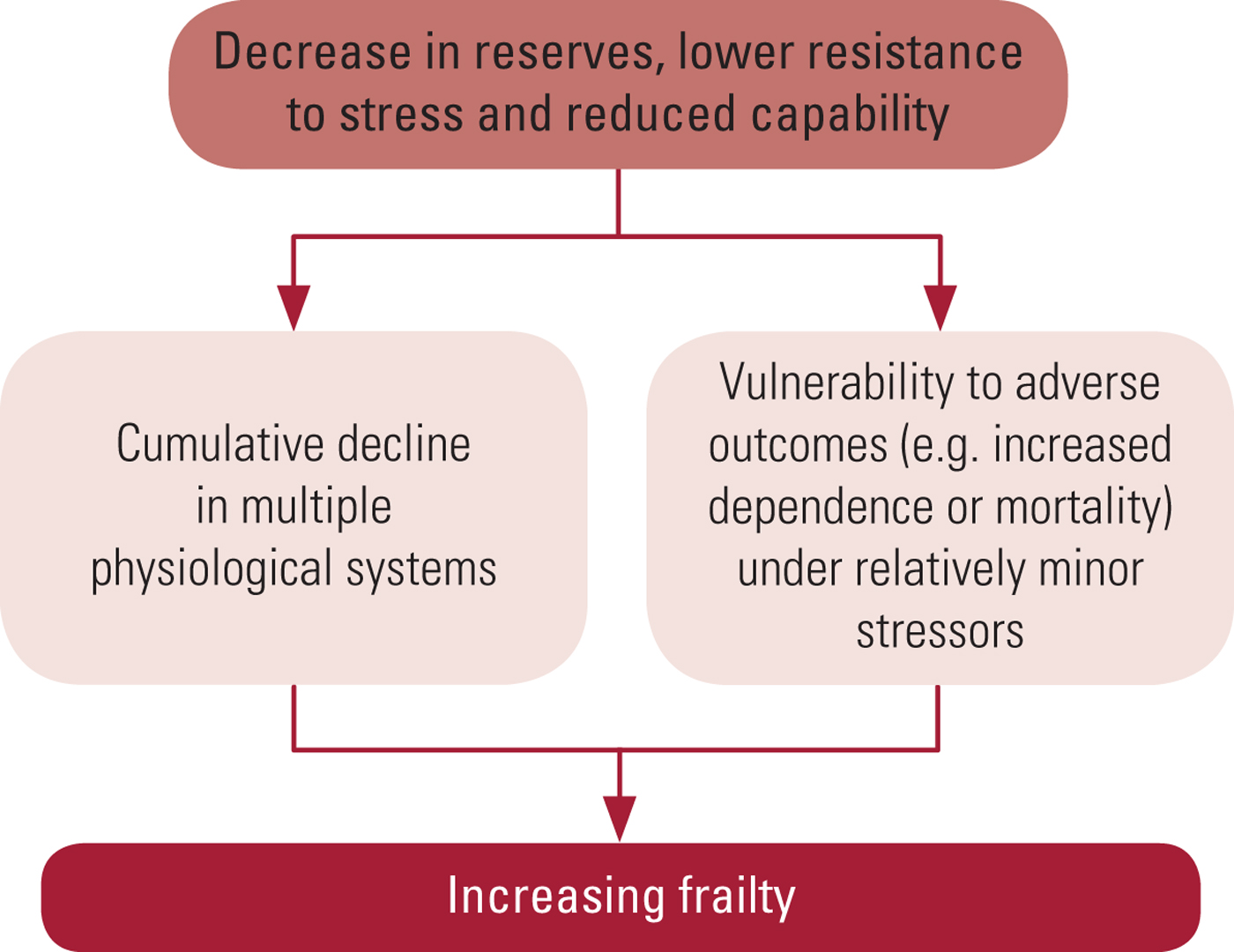

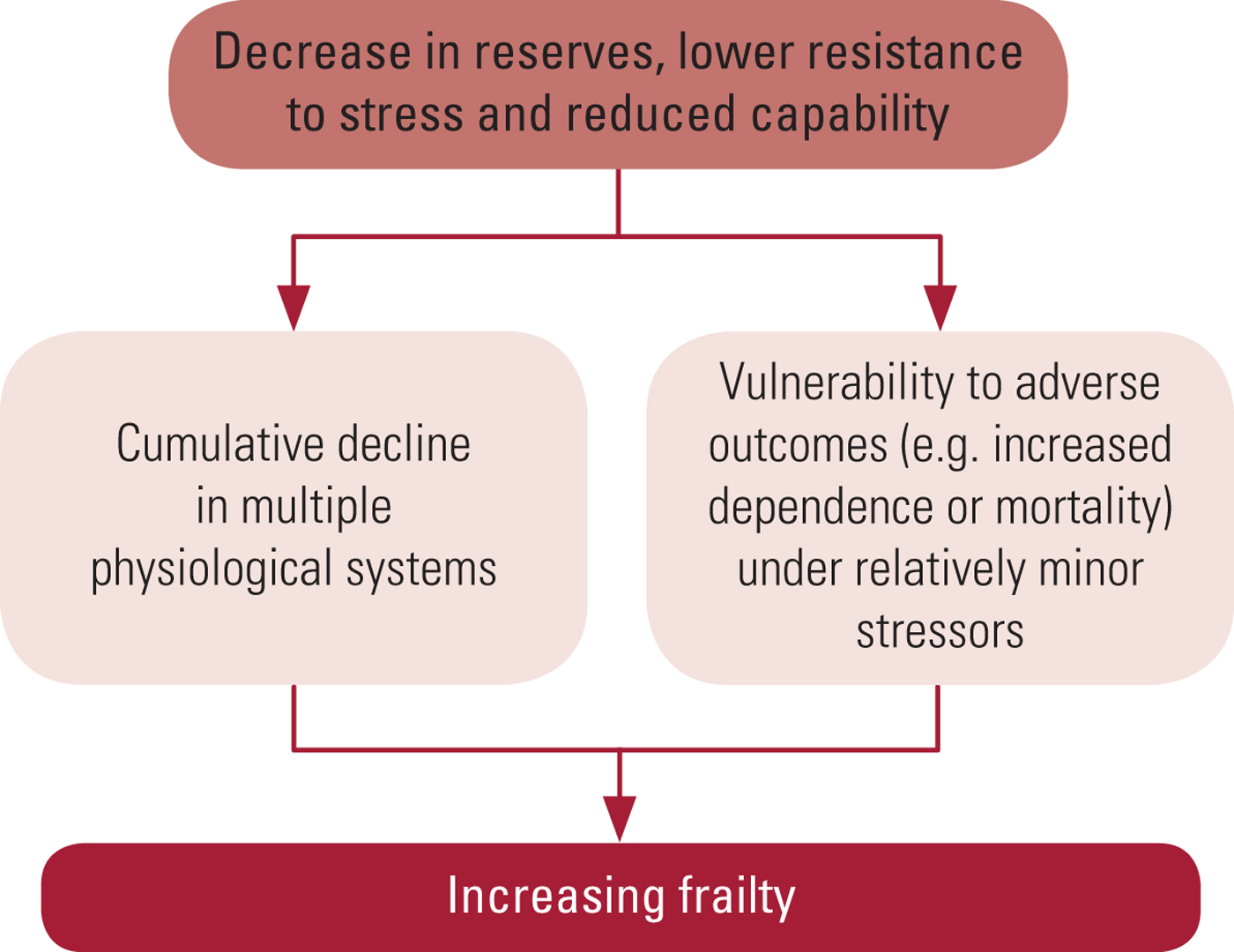

The concept of frailty has been attracting attention for at least the past three decades. It is seen as a preclinical and potentially reversible indicator of health status for older adults, predicting functional decline, disability and mortality (Mezuk Reference Mezuk, Edwards and Lohman2012). There is no universal agreement on the definition of frailty, but most definitions include three main components: (a) a cumulative decline in multiple physiological systems, usually in later life, which leads to (b) reduction in reserves, resistance and capability and (c) vulnerability to relatively minor stressors (Fig. 1) (Fried Reference Fried, Ferrucci and Darer2004; Rockwood Reference Rockwood and Mitnitski2007; Clegg Reference Clegg, Young and Iliffe2013; Morley Reference Morley, Vellas and van Kan2013).

FIG. 1 The main factors contributing to frailty (Fried Reference Fried, Ferrucci and Darer2004; Rockwood Reference Rockwood and Mitnitski2007; Clegg Reference Clegg, Young and Iliffe2013; Morley Reference Morley, Vellas and van Kan2013).

Frailty is not the same as ageing. Gradual decline in physiological reserves is expected in ageing, but in frailty this decline is accelerated and homeostatic mechanisms start to fail (Clegg Reference Clegg, Young and Iliffe2013). Frailty is much more common in older people, although up to 75% of people over 85 years might not be frail (Clegg Reference Clegg, Young and Iliffe2013). Frailty increases the risk of worsening disability, falls, admission to hospital and into long-term care, and death (Rockwood Reference Rockwood and Mitnitski2007; Clegg Reference Clegg, Young and Iliffe2013). It is the most common condition resulting in death among older people living in the community (Gill Reference Gill, Gahbauer and Han2010). Frailty is associated with the development of cognitive impairment and dementia, and an increasing degree of frailty has been associated with a faster rate of cognitive decline (Kulmala Reference Kulmala, Nykanen and Manty2014). It is also associated with increased risk of delirium and subsequent reduced survival (Eeles Reference Eeles, White and O'Mahony2012). Frail persons are high users of community resources, hospital beds and nursing home places (Morley Reference Morley, Vellas and van Kan2013).

Frailty is a manageable condition. Screening for frailty is important, and it is recommended that all persons over 70 years of age and all individuals with weight loss ≥5% due to chronic disease should be screened for frailty (Morley Reference Morley, Vellas and van Kan2013). Several scales and standardised questionnaires are available for use in clinical practice and research for detection of frailty and to measure its severity. Among others they include the Frail Elderly Functional Assessment Questionnaire, the Groningen Frailty Indicator, the Tilburg Frailty Indicator and the Edmonton Frail Scale with a timed-up-and-go test and a test for cognitive impairment (Clegg Reference Clegg, Young and Iliffe2013). Comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) has been shown to help in the development of coordinated and integrated plans for treatment and long-term follow-up of frail elderly patients by determining their medical, psychological and functional capabilities (Ellis Reference Ellis, Whitehead and O'Neill2011). However, a follow-up review by Ellis (Reference Ellis, Gardner and Tsiachristas2017) concluded there were too many variations in cognitive function and length of stay in hospital to necessarily draw conclusions from the CGA.

Procedures for transfer of patients between adult and old age services

Old age psychiatric services look after elderly ‘graduates’ – patients with enduring mental illnesses such as unresolved psychosis, relapsing or enduring mood disorders, cognitive loss and dysfunctional personalities (Jolley Reference Jolley, Kosky and Holloway2004). Graduates are likely to be stigmatised by their mental illness and the side-effects of long-term treatment. They are often socially disabled and lack personal contacts and supports. When physically ill, their mental disorder may make recognition of their physical illness and its treatment problematic.

Acute psychiatric wards for adults may be unsuitable for the care of frail older people (Jolley Reference Jolley, Kosky and Holloway2004), and old age psychiatry in-patient units would be better placed to meet their needs. As mentioned earlier, elderly graduates in contact with old age psychiatry had significantly fewer unmet needs compared with those cared for within general adult psychiatry: the domains particularly noted by Abdul-Hamid et al (Reference Abdul-Hamid, Lewis-Cole and Holloway2015) were medication management, physical healthcare, domestic management, transport and housing.

Elderly graduates are often well established as users of adult psychiatric and rehabilitation services (Jolley Reference Jolley, Kosky and Holloway2004), but transfer of their care from general adult to older adult services is not always smooth. It can result in loss of relationships with professional carers, disengagement with services and deterioration in mental health (Lievesley Reference Lievesley, Hayes and Jones2009). Existing protocols in various organisations allow transfer of patients with functional mental disorders from general adult to older adult services mainly on the basis of chronological age of 65, regardless of clinical need. Revised protocols could establish principles of transfer such as ensuring access to services considered to be most appropriate for the patient's needs. Hence, many organisations are reviewing their transfer protocols, incorporating the needs-led criteria advocated by the Faculty of the Psychiatry of Old Age of the Royal College of Psychiatrists (Box 1).

Do we need a separate subspecialty of old age psychiatry?

The management of psychiatric and medical comorbidity in older patients is complex and requires input from various professionals, including psychiatrists, physicians, physiotherapists, occupational therapists and social workers. The management of late-life depression and early-onset dementia, advance care planning and palliation in dementia all require a skilled specialist old age service. Thus, the delivery of psychological and physical care to the elderly population requires pragmatic care pathways incorporating the skills and expertise of both adult and old age services. Shared-care protocols can be devised and agreed between general adult and older adult services regarding the identification and referral of patients requiring particular specialist care. These protocols should include a thorough clinical assessment of needs. Care pathways can be devised collaboratively, with annual auditing and reviewing of procedures to ensure positive patient outcomes.

The historical evidence suggests that services improved when dedicated old age psychiatrists advocated for their patients and were listened to. Given the unique nature of the elderly population, including their frailty, and the historic alignment of services, we make a case for continuation of specialist old age psychiatric services.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 As regards frailty:

a up to 75% of people aged over 85 might be frail

b frailty is associated with an increased risk of delirium

c frailty is associated with an increased risk of depression

d frailty predicts functional decline, disability and mortality in adults

e frailty is the least common cause of death in older people living in the community.

2 Evidence indicates that depression in later life:

a is not a leading cause of suicide

b presents with a high number of symptoms of dysphoria

c accompanies as well as precedes cognitive impairment

d cannot present with unexplained medical aetiology

e has the same predictive outcome as frailty in later life.

3 As regards early-onset dementia:

a its prevalence is underestimated

b it is a clearly defined, homogeneous condition

c most cases occur after retirement

d carers usually have adequate access to resources and social support

e patients are usually appropriately directed into neurology and psychiatry services.

4 As regards older adult psychiatric services:

a the first dedicated service in the UK was established in 1958

b old age services have kept pace with general adult services, thus ensuring parity of access

c comparative studies comparing their clinical effectiveness with all-age psychiatric services often do state clinical outcomes

d the introduction of the Equality Act 2010 improved access to these services

e the Faculty of the Psychiatry of Old Age has recommended new outcome-based access criteria.

5 As regards old age:

a the meaning of ‘old age’ has remained constant overtime

b the meaning of ‘old age’ is unaffected by changes in life expectancy and the culture of ageing

c the meaning of ‘old age’ is not affected by the identity of older people

d it is expected that a period of old age associated with frailty and dependence will shift into the mid-90s from the current mid-80s by 2025

e it is expected that the transitional period after midlife and before frailty will shift from 60–75 to 70–85 by 2025.

MCQ answers

1 b 2 e 3 a 4 a 5 e

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.