LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article you will be able to:

• understand the current literature regarding associations between inceldom, mental disorder and violence

• recognise the characteristics of the incel community and identify risk factors for incel-related violence

• consider best practice for risk assessment and clinical interventions to address negative aspects of inceldom for mental well-being.

On 12 August 2021, in Plymouth, England, 22-year-old Jake Davison killed five people and injured three more before killing himself. It was subsequently revealed that he had been involved with an online community known as incels (involuntary celibates), where he lamented his virginity and expressed hatred towards women for denying him sex (Townsend Reference Townsend2021). In addition, reports indicated that he was previously known to mental health services and had an autism diagnosis. Davison's attack is not the first to be linked to the incel movement: nearly 50 violent incidents have been documented since 2014 (Hoffman Reference Hoffman, Ware and Shapiro2020). However, while growing research aims to understand this online community, there has been comparatively little focus on the mental health of incels.

Background of the incel movement

Incels define themselves by their inability to have sexual or romantic relationships despite desiring them (Preston Reference Preston, Halpin and Maguire2021). The term ‘incel’ was originally created to foster a compassionate online community for lonely people of all genders, seeking to help those struggling with forming intimate relationships (van Brunt Reference van Brunt, van Brunt and Taylor2021). However, in recent years, the incel community has arguably become dominated by heterosexual men with a bleak and misogynistic world-view.

The incel subculture emerged from the ‘manosphere’, a collection of online forums where misogynistic views are prevalent, including the belief that feminism has ruined what they perceive to be an ideal society (Glace Reference Glace, Dover and Zatkin2021). Entitlement, misogyny, jealousy, fatalism and victimhood have been identified as driving forces of the incel subculture (Cottee Reference Cottee2020; van Brunt Reference van Brunt, van Brunt and Taylor2021). Incel philosophy centres on an understanding of society as a hierarchy, where one's place is determined by appearance. Incels perceive themselves to be stuck at the bottom of this hierarchy, whereas women are viewed as ‘sexual gatekeepers’ who make dating decisions based on attractiveness, height, weight, ethnicity and wealth (O'Malley Reference O'Malley, Holt and Holt2020). They believe that the most attractive, idealised men (‘Chads’) attract the most attractive women (‘Stacys’), leaving the less attractive women for men residing in the middle of the hierarchy (‘normies’) and none for the incels (Hoffman Reference Hoffman, Ware and Shapiro2020). Therefore, incels blame women for their lack of sexual experience, providing the basis for their misogyny.

Incel ideology has been described as an extreme overvalued belief, which emphasises the shared nature of the belief by others in an individual's cultural, religious or subcultural group (Rahman Reference Rahman, Zheng and Meloy2021). Over time the belief grows more dominant, refined and resistant to challenge and is distinct from an obsession or delusion. Intense emotional commitment to an extreme overvalued belief may result in an individual carrying out violent behaviour in its name (Rahman Reference Rahman, Zheng and Meloy2021).

Although inceldom represents a spectrum of behaviour – some men seek solace found in a group sharing mutual difficulties, others look for ways to control women to achieve their short-term sexual goals (van Brunt Reference van Brunt, van Brunt and Taylor2021) – at the most extreme end are those that subscribe to the ‘blackpill’ ideology. Incels who take the ‘black pill’ accept their nihilistic fate of inferiority determined by genetics, making them less desirable, with no chance of establishing sexual relationships (Hoffman Reference Hoffman, Ware and Shapiro2020; van Brunt Reference van Brunt, van Brunt and Taylor2021). In an extremist formulation of inceldom, being ‘blackpilled’ becomes the ultimate expression of indoctrination to inceldom, culminating in one choice: to kill themselves and/or others (van Brunt Reference van Brunt, van Brunt and Taylor2021).

Incels, violence and mental illness

As the emergence of this community is relatively recent, much of our understanding of incel demographics is limited to surveys distributed by forum moderators. A recent online poll in which 665 incels participated revealed that respondents were young males, between 18 and 30 years old, who lived with their parents and had no experience of intimacy (Anti-Defamation League 2020). Most reported dissatisfaction in their lives and 95% found the blackpill ideology to be an accurate reflection of their reality. Some 68% of respondents reported depression, 74% experienced anxiety and 40% reported an autism diagnosis. Considering this, mental illness appears to be a major concern among the community. Indeed, a group of incels refer to themselves as ‘mentalcels’, a type of incel who attributes their inceldom to mental illness (Jaki Reference Jaki, De Smedt and Gwóz´dz´2019). This suggests the potential for subgroups of incels who have different contributing factors to their inceldom, but there is no available research suggesting how mental illness influences how they attribute blame for their lack of sexual relationships.

In recent years, mass violence linked to incels has been of increasing concern and raises questions about links with mental illness. Often cited in this context is the Isla Vista massacre in 2014, where 22-year-old Elliot Rodger killed 6 people, seriously injured 14 others and then killed himself. In seeking to understand Rodger's motivations, attention was drawn to his autism and prolonged treatment with psychiatric medication (White Reference White2017). Prior to his attack, Rodger released a 141-page manifesto entitled ‘My Twisted World’, detailing his grievances against society and his inability to attract the women he felt he was entitled to (Rodger Reference Rodger2014). Although Rodger did not self-identify as an incel, instead identifying with another manosphere group known as ‘Pick Up Artist haters’, he and his manifesto have become sanctified within the incel subculture.

Rodger has been influential on subsequent violent incels who see themselves as prepared to be blackpilled (Lavin Reference Lavin2018). A blackpilled incel willing to carry out violence could be described as a ‘violent true believer’, someone committed to a belief system promoting homicide and suicide to further their goal (Meloy Reference Meloy2004). Fixations on their belief system develop until they self-identify as warriors for their cause and target members of the outgroup (women and Chads) deserving of hatred and contempt (Meloy Reference Meloy2004). In 2015, after claiming ‘here I am, 26, with no friends, no job, no girlfriend, a virgin’, Chris Harper-Mercer killed nine people, injuring eight others before killing himself (Lopes Reference Lopes2022). In 2018, Nikolas Cruz killed 17 students and injured 17 more on Valentine's Day, having previously posted online ‘Elliot Rodger will not be forgotten’ and complaining about his isolation (Hoffman Reference Hoffman, Ware and Shapiro2020). This was followed by Alek Minassian's van attack in Toronto in 2018, resulting in the deaths of 10 female victims and injury to another 16 (Williams Reference Williams, Arntfield and Schaal2021). It was later revealed that Minassian had hailed Elliot Rodger as his hero (Speckhard Reference Speckhard, Ellenberg and Morton2021) and explained that following Rodger's attack he felt proud and radicalised, stating that it was ‘time to take action rather than fester in his own sadness’ (Regehr Reference Regehr2022). Before the most recent incel-inspired mass shooting in Plymouth, Jake Davison blamed the blackpill philosophy for his increasing hopelessness that ultimately led to his killing spree (Townsend Reference Townsend2021).

All documented incel-related attacks, except for Nikolas Cruz, have been successful or attempted homicide–suicides (Hoffman Reference Hoffman, Ware and Shapiro2020) and many of the incels were previously known to mental health services. Overall, the prevalence of mental disorders in incel-related violence and the rate of self-reported mental health difficulties on the forums highlight that mental disorder contributes to inceldom and, for some, the pathway to violence.

As incel violence is not characteristically triggered by political motivations, it is not formally classified as terrorism (Hoffman Reference Hoffman, Ware and Shapiro2020). However, there is an increasing consensus that the incel community could be considered a radical milieu by providing the breeding ground for those at risk of radicalisation (Brzuszkiewicz Reference Brzuszkiewicz2020). The UK government's ‘Prevent’ strategy, an anti-radicalisation framework, has recognised incels as a category within radicalisation for several years (Adams Reference Adams, Quinn and Dodd2021). Terrorism research suggests that complex interactions between terrorism and mental illness may increase vulnerability to engaging in violence through involvement with a group (Gill Reference Gill and Corner2017). Additionally, under the right psychological circumstances, such radicalising online forums could encourage extremism in vulnerable incels (Ling Reference Ling, Mahoney and McGuire2018). Therefore, we propose that a better understanding of the contribution of mental illness to the risk of violence in incels is required.

The current literature

To our knowledge, no study has examined the current literature on the impact that inceldom has on mental health and risk of violence. We therefore conducted a narrative review to: identify the associations between mental disorder, inceldom and violence; identify potential risk factors for incel-related violence to inform assessment and intervention; and propose avenues for future research. Our search methodology is available in the supplementary materials available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2022.15. We identified 17 papers with a strong emphasis on mental illness and inceldom. The following sections explore some of their findings.

Mental disorder

Depression, hopelessness and suicidality

Studies of incel literature have revealed that depression-related symptoms of low mood, hopelessness and suicidality are common themes (Speckhard Reference Speckhard, Ellenberg and Morton2021; van Brunt Reference van Brunt, van Brunt and Taylor2021). In an online survey of 272 self-identified incels from across the world, 64% reported experiencing depressive symptoms, 48% reported suicidal ideations, 60% reported anxiety symptoms and 28% reported symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (Speckhard Reference Speckhard, Ellenberg and Morton2021). Notably, there is also evidence that the incel community reinforces depression and suicidality in those with pre-existing vulnerability (Speckhard Reference Speckhard, Ellenberg and Morton2021). This aligns with frequent discussion on forums attributing feelings of loneliness and suicidality to inceldom (Glace Reference Glace, Dover and Zatkin2021). Although gratitude is expressed towards the community for providing a safe, cathartic environment for like-minded individuals (Cottee Reference Cottee2020; Maxwell Reference Maxwell, Robinson and Williams2020; O'Malley Reference O'Malley, Holt and Holt2020; Speckhard Reference Speckhard, Ellenberg and Morton2021), this occurs alongside strong suicidal rhetoric throughout the forums (Hoffman Reference Hoffman, Ware and Shapiro2020; Maxwell Reference Maxwell, Robinson and Williams2020; Glace Reference Glace, Dover and Zatkin2021). Furthermore, 71% of incels viewed their circumstances as permanent (Speckhard Reference Speckhard, Ellenberg and Morton2021), suggesting that preoccupation with self-degradation and the blackpill ideology further contributes to the hopelessness experienced by most incels (O'Malley Reference O'Malley, Holt and Holt2020).

Hopelessness is a common theme in incel-related violence and is argued to be a central risk factor for mass violence by incels (van Brunt Reference van Brunt, van Brunt and Taylor2021), with most attackers displaying suicidal ideation (Williams Reference Williams and Arntfield2020; van Brunt Reference van Brunt, van Brunt and Taylor2021). However, hopelessness is not enough to trigger extreme violence among those incels who transition from depression and loneliness to a mission-oriented plan to ‘punish’ those they deem responsible for their frustrations (van Brunt Reference van Brunt, van Brunt and Taylor2021). Hopelessness, significantly exacerbated by cognitive distortions such as over-generalisations, all-or-nothing thinking (across multiple contexts), misattributions, lack of empathy, neutralisation and victim stances, provides a justification for subsequent acts of extreme violence (Williams Reference Williams and Arntfield2020, Reference Williams, Arntfield and Schaal2021). In all attacks by incels, perpetrators misattributed blame to women for frustrations in their life, specifically for sexual frustration (Murray Reference Murray2017; Williams Reference Williams and Arntfield2020).

Psychosis

We found very little discussion on the association between psychosis and inceldom and no confirmed cases of psychosis in incel-related violence. Analysis of incel forums shows that beliefs are more comparable to extreme overvalued beliefs that are shared, amplified and defended by the entire community and not an example of delusion (Rahman Reference Rahman, Zheng and Meloy2021). Furthermore, impaired communicative skills may make it challenging for individuals suffering from a psychotic disorder to engage with the fast-paced nature of an online community (Haker Reference Haker, Lauber and Rössler2005). A survey on the use of technology among individuals with schizophrenia showed that although many respondents did use technology in a similar, positive way to non-clinical populations, almost half reported that they ‘rarely’ or ‘never’ used technology when experiencing symptoms (Gay Reference Gay, Torous and Joseph2016). More research is required to understand how a psychotic disorder may influence an individual's engagement with the online incel community and any related violence.

Eating disorders and body dysmorphia

At present there are no available data on the prevalence of eating disorders or body dysmorphia within the incel community. However, both incels and individuals with eating disorders demonstrate dichotomous thinking. For example, incels view the world through a lens of ‘Chads’ and ‘Stacys’ and individuals with anorexia fixate on ‘fat’ and ‘skinny’ (Rahman Reference Rahman, Zheng and Meloy2021). It could also be argued that both groups show extreme fixations on physical appearance (‘lookism’), fuelling feelings of worthlessness. There is evidence of toxic forums within the incel community dedicated to critiquing each other's appearance (O'Malley Reference O'Malley, Holt and Holt2020). Online communities also exist for individuals with eating disorders (e.g. various pro-ana groups; Juarascio Reference Juarascio, Shoaib and Timko2010) and although they aim to provide social support for people with eating disorders, they also have the potential for harm by encouraging maladaptive eating behaviours. Although an eating disorder would not fuel violence against others, associated distorted thinking, such as inferior body image in relation to others, could contribute to feelings of hopelessness and feed extreme overvalued beliefs. In addition, given that research suggests over 60% of individuals with an eating disorder report self-harm or suicidal thoughts (Cliffe Reference Cliffe, Seyedsalehi and Vardavoulia2021), incels might be more vulnerable to self-inflicted violence if they have an eating disorder. In fact, one-third of incels participating in an online survey reported ever engaging in acts of self-harm and the intensity of this self-harm significantly correlated with their agreement that belonging to the incel community made them want to harm themselves (Speckhard Reference Speckhard, Ellenberg and Morton2021). Nevertheless, while there are similarities between the two groups, there is no evidence to suggest that having an eating disorder increases vulnerability to inceldom.

Autism

The literature suggests that there may be a specific relationship between autism and incel-related activity (Williams Reference Williams, Arntfield and Schaal2021). In one online survey, almost a quarter of incels self-reported autism symptoms (Speckhard Reference Speckhard, Ellenberg and Morton2021) and analysis of seven incel-related cases of violence suggested that more than half showed characteristics of autism (Williams Reference Williams, Arntfield and Schaal2021). Some of the difficulties associated with autism may increase vulnerability to being drawn into the ‘rule-based’ incel ideology and increase risk of radicalisation (Williams Reference Williams, Arntfield and Schaal2021). Key factors are likely to be a specific cognitive style characterised by literal thinking and interpretations, as well as difficulties with various aspects of social cognition, resulting in social naivety and problems forming intimate relationships (Murphy Reference Murphy, Chaplin, Spain and McCarthy2020). Although there is nothing in the literature, a preoccupation with sex may also be a driver towards inceldom.

Some individuals with autism may be particularly vulnerable to the online nature of the incel community because of problems understanding relationships and associated dynamics (Williams Reference Williams, Arntfield and Schaal2021). In addition, co-occurring conditions such as depression and anxiety are often present in autism (White Reference White2017). Although autism is not directly linked to violence (Heeramun Reference Heeramun, Magnusson and Gumpert2017), in some contexts the combination of certain characteristics may lead to outbursts and criminal behaviour (Murphy Reference Murphy, Chaplin, Spain and McCarthy2020). For example, difficulties with emotion regulation and poor impulse control, combined with specific cognitive styles associated with autism, such as literal thinking, may increase vulnerability to engaging in violence.

It is suggested that Rodger's autism contributed to the significant frustrations that he experienced and provided the ‘psychobiological foundation’ for the development of his defensive personality that facilitated his mass violence (Allely Reference Allely and Faccini2017; White Reference White2017). However, as rates of autism in the incel community mostly come from self-report or retrospective diagnosis following a homicide–suicide, this must be interpreted with caution given the lack of valid assessments (Williams Reference Williams, Arntfield and Schaal2021). In regards to the association between having autism and vulnerability to inceldom, it is important not to infer that all men with autism are at risk of inceldom. It may be a particular subgroup of individuals in certain circumstances who are more vulnerable. More research is required, including robust diagnostic assessment of individuals.

Personality disorder

There are few articles addressing personality disorder within the incel community. Analysis of Rodger's writings reveals evidence of grandiosity, pretentiousness and entitlement that is suggested to be indicative of narcissistic personality disorder. This is also highlighted by his extreme jealousy of those in sexual relationships (Williams Reference Williams, Arntfield and Schaal2021). It has been argued that narcissistic rage was the main contributor to the mass shooting that he perpetrated. Furthermore, the co-occurrence of autism and narcissism may be a particularly explosive combination, increasing the risk of someone with autism engaging in violent behaviour (Allely Reference Allely and Faccini2017).

To date, there is no discussion of the contribution of dissocial, emotionally unstable or paranoid personality disorders to inceldom, which may be expected in cases where there is evidence of violence, suicidality and difficulties forming healthy relationships. However, a study of men from a general US population who completed an ‘incel trait’ measure found that the combination of personality traits frequently seen in inceldom (e.g. rejected, insecure, paranoid, resentful) with grievances about gender roles and hostile attitudes towards women was associated with increased reports of fantasies about mass murder and rape (Scaptura Reference Scaptura and Boyle2020). However, these ‘traits’ may be more a reflection of cognitive distortions and maladaptive schemas, reinforcing the role of distorted thinking in the incel community. Such traits also present opportunities for targeted intervention. Nevertheless, the ‘incel trait’ measure was developed from the analysis of media reports of incel violence and there has been no validation of the measure in incel populations.

Clinical management

Risk assessment

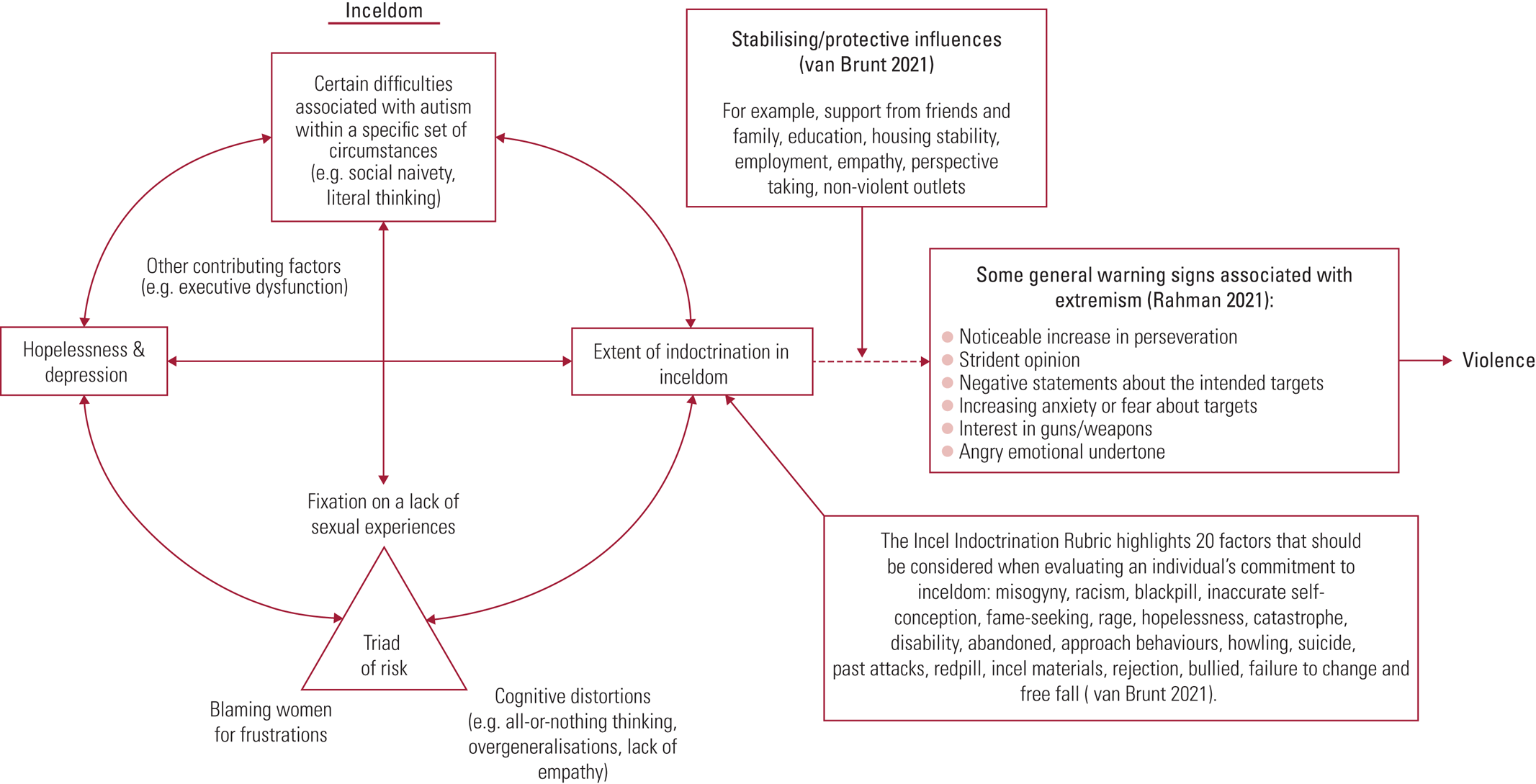

Although some of the specific difficulties associated with having autism might, in certain circumstances, increase vulnerability to inceldom (Williams Reference Williams, Arntfield and Schaal2021), hopelessness and depression appear to be central risk factors associated with incel violence (van Brunt Reference van Brunt, van Brunt and Taylor2021). However, these mental states are common and the commission of violence is a rare event among incels. The literature suggests that a 'triad of risk' that appears to be unique to incels is of particular relevance. This consists of cognitive distortions, a fixation on lack of sexual experience and blaming women for such frustrations. Changes in the intensity of these fixations must be monitored, particularly when accompanied by deterioration in social and occupational functioning, as they might be an indication of increasing pathological preoccupation with violence against women (Rahman Reference Rahman, Zheng and Meloy2021). Warning behaviours of an incel-related attack will be similar to those for violence related to any extreme overvalued belief, such as a noticeable increase in perseveration, strident opinion, negative statements about the intended target(s), increasing anxiety or fear about the target(s), interest in guns and an angry emotional undertone (Rahman Reference Rahman, Zheng and Meloy2021). The interaction between such factors is displayed in Fig. 1.

FIG 1 Risk factors associated with inceldom.

A tool measuring the degree of indoctrination to inceldom was recently developed from the analysis of 50 cases of incel violence. van Brunt & Taylor's Incel Indoctrination Rubric (IIR) (cited in van Brunt Reference van Brunt, van Brunt and Taylor2021), describes 20 risk factors indicating an individual's commitment to the movement (Fig. 1). To date, there are no available data on the validity of the IIR and it was not specifically developed for the mentally disordered incel population. More research is needed to assess how an IIR score would associate with violence. However, such a tool could prove invaluable for initial psychiatric assessment of incels with mental disorders.

Identifying stabilising influences for incels is vital, which if fostered will redirect them away from the pathway of violence by encouraging harm reduction strategies, increasing positive relationships and reinforcing non-violent attitudes (van Brunt Reference van Brunt, van Brunt and Taylor2021). Examples of such influences include social and family support, education, work and housing stability (van Brunt Reference van Brunt, van Brunt and Taylor2021). Assessing the presence of protective factors will inform the degree of risk and the best approaches to mitigate such risk.

Clinical interventions

Specific interventions aimed at addressing incel vulnerabilities remain at an early stage, as all available information is theoretical. Several psychotherapeutic approaches have been suggested, such as existential therapy, narrative therapy, person-centred therapy and reality therapy (van Brunt Reference van Brunt, van Brunt and Taylor2021). In general, clinical interventions should aim to discuss incel beliefs with the individual and validate their experiences while dismantling the narrative of females as the root of their problems, which will be important in preventing radicalisation (O'Malley Reference O'Malley, Holt and Holt2020).

Cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) has been identified as a useful approach to reframe the incel world-view, focusing on the maladaptive cognitions surrounding their victimhood, hopelessness and misattribution (Cottee Reference Cottee2020; Maxwell Reference Maxwell, Robinson and Williams2020; van Brunt Reference van Brunt, van Brunt and Taylor2021). It seems that distorted cognitive beliefs, rather than a certain personality typology, are central to inceldom (Scaptura Reference Scaptura and Boyle2020). CBT interventions could help incels to find alternative ways to process the world by recognising irrational and catastrophising thought patterns and thinking differently about their low self-esteem and rejection (van Brunt Reference van Brunt, van Brunt and Taylor2021).

However, engaging incels with therapeutic interventions remains a challenge owing to a general mistrust of the mental health system among incels (Speckhard Reference Speckhard, Ellenberg and Morton2021). Despite the clear link between inceldom and depression, only half of the 272 incels responding to an online survey reported ever trying therapy; 15 (6%) reported finding it beneficial. Those who had not tried therapy deemed it ‘a scam’, ‘a waste of money’ and unable to fix the physical features to which they attributed their inceldom (Speckhard Reference Speckhard, Ellenberg and Morton2021). Moreover, working with patients with issues as complex as those experienced by some incels may be challenging for therapists. The patient's severe envy of the therapist's perceived success may interfere with the therapeutic alliance, triggering feelings of inferiority (White Reference White2017). Given the importance of online communities to incels, group therapy may be a supportive peer environment to explore feelings associated with inceldom, and internet-based CBT groups are a potential avenue for exploration (Maxwell Reference Maxwell, Robinson and Williams2020).

Improved access to mental health resources for young men online has been identified as one of the most important policy recommendations to counter incel extremism (Hoffman Reference Hoffman, Ware and Shapiro2020). Addressing ‘toxic masculinity’ and gender inequality will be important to encourage healthier expression of emotions related to lack of self-esteem and worthlessness in young boys (O'Malley Reference O'Malley, Holt and Holt2020). Engaging with social media may facilitate and reinforce dangerous beliefs that condone gender-based violence. Therefore, targeting youth who are vulnerable to incel ideology by enhancing digital literacy and critical consciousness throughout education is crucial (O'Malley Reference O'Malley, Holt and Holt2020).

Discussion

The vast majority of incels are not a significant threat to women. However, increasing cases of incel violence have been considered acts of violent extremism (Zimmerman Reference Zimmerman, Ryan and Duriesmith2018) and there are rising concerns that incel subculture embodies characteristics of terrorism (Speckhard Reference Speckhard, Ellenberg and Morton2021). Therefore, there is a need to determine the risk factors among incels that lead to individuals supporting and engaging in violence. This includes improving our understanding of incel mental health.

Incel ideology relies on the individual having a negative view of themselves, the world and their future due to the belief that their genetically determined physical appearance condemns them to a life of isolation, loneliness and rejection by women and society (Hoffman Reference Hoffman, Ware and Shapiro2020). This ‘negative triad’ influencing their world-view is common in people experiencing depression (Beck Reference Beck, Rush and Shaw1979), thus explaining the high prevalence of hopelessness in the incel community. However, the combination of hopelessness with the ‘triad of risk’ consisting of (a) fixation on a lack of sexual experience, (b) cognitive distortions and (c) blaming women for their frustrations appears to be central in exacerbating the difficulties associated with inceldom. Incels may escalate to violence if they feel misunderstood by society and view harming themselves and/or others as their only option (van Brunt Reference van Brunt, van Brunt and Taylor2021).

Some difficulties associated with autism may increase vulnerability to the development of additional risk factors that ultimately push an individual towards inceldom and potential violence. Examples include difficulties navigating social interactions and increased susceptibility to depression and anxiety. Research shows that when an individual with autism does commit violence there is often a comorbid condition such as mood disorder, psychosis or psychopathy (Im Reference Im2016). For a comprehensive risk assessment, it is important that the combination of difficulties associated with the individual's autism is considered in the context of their personal circumstances. For example, social naivety, difficulties with emotion regulation and preoccupation in the context of certain cognitive characteristics (such as rigid thinking and lack of awareness of consequences), sensory processing deficits and social exclusion have a profound impact on decision-making and behaviour (Murphy Reference Murphy, Chaplin, Spain and McCarthy2020). The contextual role of autism will differ depending on the individual, and individual case formulation should be used to establish the contributing factors to risk (Al-Attar Reference Al-Attar2020). This will also identify vulnerabilities associated with autism that could be nurtured as strengths and increase the individual's resilience to extremism (Al-Attar Reference Al-Attar2020). It is not autism alone that confers risk, but the combination of the specific difficulties experienced by the individual in certain circumstances.

Less clear is the impact of other neurodevelopmental disorders, as there has been no research on attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or intellectual disability and their associated challenges among incel groups. Moreover, further research is required to understand how psychosis may contribute to inceldom and incel-related violence, particularly considering that engaging with an online community may be challenging for individuals with active symptoms of psychosis (Gay Reference Gay, Torous and Joseph2016).

There is emerging research on the contribution of personality disorder to incel violence. Narcissistic personality disorder appears to be of particular interest. This is noteworthy given the complex interaction seen in incels between their sense of male superiority in relation to women and their feelings of inferiority triggered by perceived or actual rejection by women. Research suggesting specific cognitive patterns leading an incel to believe that wrong is deliberately being done to them may contribute to the pathway to violence (Allely Reference Allely and Faccini2017). However, clarification is needed to establish whether it is apparent ‘personality traits’ or, perhaps more likely, the development of a specific set of maladaptive schemas associated with increased risk of inceldom.

Recommendations for risk assessment and clinical practice

In the context of clinical risk assessment, given the novelty of this online phenomenon, clinicians may be unsure how to approach discussion with the patient to ascertain whether inceldom is a presenting problem. Conducting interviews with incels and gathering collateral information is crucial to formulate what inceldom means to them and how it shapes their interactions with others, especially women (Cottee Reference Cottee2020). The gender of the clinician must be considered in this context and how the individual may react to a female assessor. Most importantly, the clinician should have a comprehensive understanding of inceldom and the associated world-views and values.

Based on the current literature, initial guidance is provided below on areas to consider when assessing the presence of inceldom and the degree of risk. This is by no means an exhaustive guide and, depending on the context of the assessment, not all information will be easily accessible. The key elements of this guide have been summarised in Box 1.

BOX 1 Recommended areas to consider when completing risk assessments for potential incels

Internet use

Relationship history

Misogyny and other discriminatory attitudes

Frustrations and grievances

Cognitive distortions

Mental illness

Autism

Indoctrination into incel ideology

Glorification of Elliot Rodger

Acceptance of blackpill ideology and suicidality

Fixation on/access to weapons

Stabilising factors

Risk assessment guidance

• Assessment of the individual's internet use must be prioritised to understand how online cultures influence their world-view and their engagement with the incel community (Rahman Reference Rahman, Zheng and Meloy2021). Forums of particular interest and advice on how to broach internet use with a potential incel can be found in Box 2.

• Evaluate the individual's relationship history, both sexual and non-sexual. Try to understand their feelings about lack of intimacy. For example, an incel would experience significant shame and frustration by their virginity and feel jealous of peers in successful sexual relationships.

• Determine the presence of misogyny and anti-feminist attitudes. Other discriminatory attitudes, such as racism and homophobia, are also common in incels (van Brunt Reference van Brunt, van Brunt and Taylor2021).

• Understand the frustrations incels experience in different domains of their lives and the weighting they place on each of these areas. Typically, incels experience significant challenges in areas such as employment, family and friendships, and financial success, but their fixation is on their lack of intimate relationships (Williams Reference Williams and Arntfield2020).

• Consider the presence of cognitive distortions such as catastrophising, overgeneralisations, all-or-nothing thinking, entitlement and lack of empathy (Williams Reference Williams, Arntfield and Schaal2021). Most importantly, consider the presence of misattributing blame, particularly to women, for their problems.

• Consider the presence of mental illness, such as depression, anxiety and personality disorder, and how this has affected the individual's engagement with the incel community. Understand their experiences of mental health services in the past.

• Consider an autism diagnosis and the specific associated difficulties the individual experiences. In certain contexts, some difficulties associated with autism (such as social naivety, interpreting the mental states of others and perspective-taking) may increase an individual's vulnerability to radicalisation by online communities.

• Evaluate the extent of indoctrination to the incel ideology. With research in this field continually growing, tools such as the IIR (van Brunt Reference van Brunt, van Brunt and Taylor2021) are vital. The presence of core incel beliefs should be of particular interest: misogyny, entitlement and jealousy (van Brunt Reference van Brunt, van Brunt and Taylor2021).

• Determine whether there is evidence of glorification of Elliot Rodger and other individuals associated with incel violence.

• Evaluate the individual's adoption of the blackpill ideology, which is deemed the ultimate level of indoctrination to the incel cause and will contribute to the risk of suicidality and homicide (van Brunt Reference van Brunt, van Brunt and Taylor2021).

• Evaluate the presence of a fixation on and/or access to weapons, particularly firearms. Most incel attacks have been mass shootings. Therefore, engagement with the incel community should be considered when assessing suitability for gun licences. Other potential weapons include knives, poison and acid.

• Evaluate the presence of stabilising and protective factors in the individual's life, such as support from friends and family, education, financial stability, a positive outlook, limited access to lethal means, empathy for others, perspective-taking, intimate relationships, awareness of consequences, resilience, problem-solving, non-violent outlets, emotional stability and positive self-esteem (van Brunt Reference van Brunt, van Brunt and Taylor2021).

BOX 2 Advice for navigating conversations on internet use during initial assessments

Visiting an internet site is similar to visiting physical sites. Often a judgement-free environment and some basic understanding is required for people to feel comfortable.

The clinician should aim to ask the individual to explain where they go on the internet rather than asking them to explain the details of how they access such websites or what they contain (which can make them feel further alienated).

In addition to gaining information on how a patient uses a website, the clinician should search the site after an initial meeting to familiarise themselves with the layout and general attitudes, especially forums.

It is important to find out what incel forums the individual uses. There are many different incel forums and they are often forced off web hosting services because of offensive content. This means that the website names change frequently. If the individual says which website they use, review the site if possible, to understand the type of community and content they are engaging with. For example, do they use an incel forum on Reddit, where they will be bound to site-wide rules, or is it an incel-specific forum such as Incels.is? The latest URLs can be found on Twitter @IncelsCo.

Within the English-speaking web forums, other sites to be aware of are:

Stormfront, an extremely racist website noted for fostering extremist and terrorist views with some cross-over with the incel community

4chan, which is the biggest chan (imageboard). In recent years 4chan has become a lot more racist and prone to radicalisation due to internal politics. It is also important to establish which boards on 4chan the individual uses, as some boards are more concerning than others (e.g. /pol/ and /r9k/)

Parler, which is one of the few ‘free speech’ platforms to still exist in the wake of the attack on the US Capitol on 6 January 2021. Although not incel specific, it is likely to bring people into contact with far-right extremists

Lookism.net, a website specifically fixated on the idea of how to be attractive and how being attractive is the only way to find a romantic interest. Frequently referenced and used by incels

In addition to a comprehensive formulation of the individual's inceldom, utilising a structured professional judgement tool to assess risk of engaging in lone-actor terrorism would be beneficial. The Terrorist Radicalization Assessment Protocol-18 (TRAP-18; Meloy Reference Meloy2018) assesses a mixture of dynamic and static proximal warning signs and distal characteristics, focusing on patterns of behaviour. The tool can be used to allocate resources by informing which individuals require priority attention and active case management.

Clinical interventions

In terms of clinical intervention, incels are complex, vulnerable individuals requiring complex clinical management and there will not be a single intervention that works for all (Basu Reference Basu2021). Therefore, a comprehensive formulation of the individual's problems will be beneficial not only for risk assessment and management, but also to guide interventions tailored to the individual's needs. As distorted ideas and beliefs typically characterise these individuals it is not surprising that psychological interventions such as CBT have been put forward as the treatment of choice. Providing strategies to recognise their irrational thinking and utilise more rational approaches is essential to prevent an incel spiralling into maladaptive thinking, regardless of risk.

Encouraging engagement with mental health services is a priority, given the prevalence of suspicious and negative attitudes towards therapy among incels (Speckhard Reference Speckhard, Ellenberg and Morton2021). Furthermore, incels often do not broadcast their inceldom outside of the forums. Online, group-based therapy has been argued as an approach to overcome these barriers. Careful consideration should be given to deciding how such groups should be facilitated. Incels can view advice from non-incels as unsolicited, unhelpful and often insulting (Maxwell Reference Maxwell, Robinson and Williams2020). Group therapy could prevent triggering feelings of inferiority by relieving the focus on the therapist, who may be viewed as a symbol of success. Using approaches from compassion-focused therapy may be helpful for incels, given its proven effectiveness in populations high in self-criticism (Leaviss Reference Leaviss and Uttley2015). Further research is needed to establish the efficacy of such interventions.

Limitations and future directions

Understanding the associations between inceldom and mental disorder is limited by the lack of valid psychiatric assessments used to establish diagnoses. Current literature is theoretical or based on online self-report surveys, media or analyses of forum content by non-incels, who may misinterpret the nuances of incel language. Recruiting incels for interviews is possible and future research should endeavour to work directly with incels to gain greater insight into their experiences (Cottee Reference Cottee2020). More research is needed to understand the contributions of psychosis, personality disorder, substance misuse, ADHD and intellectual disability to incel violence. In addition, given the high level of fixation seen in this population, research should focus on the influence of cognitive functioning in incels, considering features such as executive dysfunction, perseveration and lack of flexible thinking. As we gain a greater understanding of factors contributing to inceldom and associated violence we may begin to identify subgroups of incels, which would be beneficial for determining appropriate support and intervention.

Conclusions

Inceldom is a poorly understood but significant online movement that shows potential for extremism and violence, particularly among those with mental health difficulties. Although depression, autism and personality disorder are not associated with violence themselves, they may accelerate or produce a vulnerability to extreme overvalued beliefs, which refine over time and become increasingly difficult to challenge. Research in this field is in its infancy and the mechanisms behind this association require further investigation. Future research should aim to work directly with incels to determine how psychopathology develops over time and potential therapeutic interventions to prevent vulnerable incels transitioning to violence.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2022.15.

Data availability

All articles cited in the review are referenced. Search methodology is available in supplementary materials. No other data was used for this article.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of the West Yorkshire Police.

Author contributions

J.H. and J.B. jointly conceived the study. J.B. wrote the majority of the text, with significant support from L.B. with the narrative review and writing. D.P., D.M. J.H. assisted in the development of the project and made significant contributions in editing the text.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 Incel ideology is centred on the belief that:

a one's place in the social hierarchy is determined by physical attractiveness and financial success

b incels are at the top of the social hierarchy

c women are at the bottom of the social hierarchy

d incels attract the most attractive women (‘Stacys’), leaving the less attractive women for ‘Chads'

e men are 'sexual gatekeepers'

2 The following are all driving forces of inceldom, except for:

a entitlement

b misogyny

c jealousy

d isolation

e fatalism.

3 The suggested ‘triad of risk’ factors unique to inceldom includes:

a fixation on lack of sexual experience, evidence of cognitive distortions and autism

b fixation on lack of sexual experience, blaming women for frustrations and autism

c fixation on lack of sexual experience, evidence of cognitive distortions and blaming women for frustrations

d fixation on lack of sexual experience, fixation on weapons and evidence of cognitive distortions

e fixation on lack of sexual experience, self-loathing and fixation on weapons.

4 Which of the following is not one of the 12 recommended areas to cover during risk assessment of a potential incel?

a internet use

b occupational skills

c presence of stabilising factors

d presence of mental disorder

e extent of indoctrination to the incel ideology

5 Challenges to implementing clinical interventions to address inceldom include:

a pervasive distrust of mental health services within the incel community

b identifying candidates for therapy, as incels do not broadcast their inceldom

c the inefficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy among incels

d b and c

e a and b.

MCQ answers

1 a 2 d 3 c 4 b 5 e

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.