LEARNING OBJECTIVES

-

Understand the key amendments to the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ guidance on CPD, and the rationale behind the changes

-

Understand how to develop meaningful personal development plans (PDPs) that respond to the psychiatrist's professional needs

-

Consider the varied learning experiences that can be considered as CPD and understand that CPD activity is not limited to taught courses

Medicine is a rapidly developing field. Much of what many of us learned in medical school is now obsolete, and an expanding knowledge base has led to increasingly specialised services. Add to this the fact that many doctors – by choice or as the result of service changes – change their areas of clinical practice, and the need to continue learning and developing after completion of formal training is undeniable.

We learn on a day-to-day basis in our clinical practice. As well as taking the relatively obvious forms of reading a literature review or asking the advice of a colleague, learning will also be through continuous feedback, for example from patients about a particular approach we take or a good clinical outcome. Being open to everyday feedback and thoughtfully working in teams is therefore an important part of remaining a safe and effective practitioner.

Given this essential and unavoidable day-today learning, it is reasonable to ask what the additional benefit of continuing professional development (CPD) is and why it is important to be in good standing for CPD with the Royal College of Psychiatrists. Revised guidance from the College (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2015) aims to help psychiatrists ensure that the CPD they undertake has a real impact on their patients’ care.

What is CPD?

The General Medical Council (GMC) has defined CPD as follows:

‘CPD is any learning outside of undergraduate education or postgraduate training that helps you maintain and improve your performance. It covers the development of your knowledge, skills, attitudes and behaviours across all areas of your professional practice. It includes both formal and informal learning activities’ (GMC 2012).

This definition acknowledges the continuous learning within clinical practice described above and the importance of this in a doctor's development. It emphasises that CPD should consider the full scope of a doctor's practice and that, while the majority of psychiatrists are primarily clinicians, other roles such as teaching or research must not be forgotten.

The College's CPD programme supports a structured and objective approach to learning and seeks to make CPD more effective for the individual. It does not aim to encourage the doctor to record and explicitly consider all learning that they undertake. This would be unrealistic and would not reflect the way in which thoughtful practitioners develop. Key to the College's programme is the development and completion of a personal development plan (PDP) within a CPD peer group that can support the doctor in reflecting on current practice (and therefore areas for development) and the implications of new learning for their practice.

If CPD is intended to help ‘maintain and improve your performance’, it is reasonable to assume that the outcome of good CPD is improved patient care. This makes intuitive sense but, although it is possible to show evidence of improved outcomes individually, demonstrating that CPD as a whole improves care is far more challenging (Reference Mathers, Mitchell and HunnMathers 2012).

How to link CPD to improved patient care

Good CPD can have many potential outcomes – for example, improved confidence, greater job satisfaction, innovation, networking and sharing with peers – but the ultimate outcome should be improved care for patients. How can this be achieved?

Developing a focused PDP

As doctors, we receive feedback from many sources. Some sources are formal, such as complaints, incident reviews or structured multisource feedback, others are less formal, such as individual patient outcomes, peer discussion and our own reflections on our practice. Being able to consider this feedback honestly and thoughtfully is essential to understanding our learning needs. When developing a PDP, it is natural to be drawn to our areas of interest or expertise. Of course, to stay up to date, ongoing learning in such areas is necessary but we must also pay attention to areas of our practice that we are less enthusiastic about and have perhaps not focused on previously.

It is the individual doctor's responsibility to identify their needs and consider how they will address them (GMC 2012). However, psychiatrists are helped to do this in two ways: by their CPD peer group and by the appraisal process.

-

The peer group will use an informal process to help the doctor to develop a PDP that reflects their needs (rather than interests or wishes).

-

At appraisal, information about the full scope of the doctor's practice and performance is formally discussed (e.g. outcome measures, complaints, incident reviews, activity levels). Using this information as a foundation, the appraiser and doctor will create a PDP. The full scope of practice – both clinical and non-clinical aspects – should be considered.

This can mean that the doctor ends up with two PDPs: one from the peer group and one from appraisal. The PDP developed in the peer group will inform the one developed in appraisal. If the processes resulting in each have been robust, the PDPs should not be too dissimilar. A significant difference in the PDPs should raise concerns that there has not been fair or honest discussion about the psychiatrist's work or needs in one or both of the processes.

It is important that CPD reflects the doctor's practice (or intended practice for the future), rather than their own personal interests. Although all doctors, whatever their experience, need to stay up to date with relevant therapeutic developments, it is inevitable that their needs will change over their career. Developing skills that are not going to be used in practice will not benefit patients.

Successfully addressing development needs

To evaluate how successful learning has been, it is necessary to be clear about what is to be achieved. The PDP must be specific and the outcomes must be to some extent measurable (Box 1).

BOX 1 How to develop a good PDP

-

1 Gather information about the full scope of your practice (e.g. multisource feedback, clinical activity, complaints and compliments, incident reports)

-

2 Make time to reflect on what the PDP says about your practice – what should you aim to improve?

-

3 Discuss it in a supportive and formative environment with others (e.g. a CPD peer group)

-

4 Agree specific objectives – SMART objectives are good:

-

Specific

-

Measurable (or demonstrable)

-

Achievable (personally and within the service)

-

Relevant to current or proposed practice

-

Time-bound

-

How to best meet development needs will depend on a variety of factors. We all have preferred ways of learning – for example, by reading or through experience. In addition, different objectives will be best achieved in different ways; attending a lecture might help to meet an objective of understanding the evidence base of pharmacological treatments for treatment-resistant depression, but would be unlikely to offer a doctor much if their objective was to improve their communication skills, in which case observation and practice with a respected colleague are more likely to be effective.

The Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (2012) has created a useful template to help doctors structure their reflections when considering how new information relates to current practice and whether further actions are required (Fig. 1). Use of this template is encouraged by the Royal College of Psychiatrists (2015). There are many alternative templates that can be adjusted as needed, but all tend to cover the same areas: what the activity was, what the learning was and how it will change practice. Such notes can be used in peer-group discussions, to demonstrate value and justify the allocation of CPD credits, and within the appraisal process, to demonstrate ongoing personal development and quality improvement.

FIG 1 Example of a reflective note using the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (2012) template.

However, completing the learning event will not in itself improve practice. The knowledge and skills acquired need to be put into practice in the psychiatrist's work.

Modifying practice after acquiring new skills or knowledge

CPD is only important inasmuch as it improves a doctor's practice; it is not an end in itself. The College's revised guidance emphases this and places the responsibility for ensuring that learning relates to practice on the peer group. CPD credits cannot be awarded to a particular activity unless the peer group are assured that the psychiatrist has considered how the activity relates to their current practice. In a relationship between peers, this requirement might not feel comfortable but it is a professional responsibility.

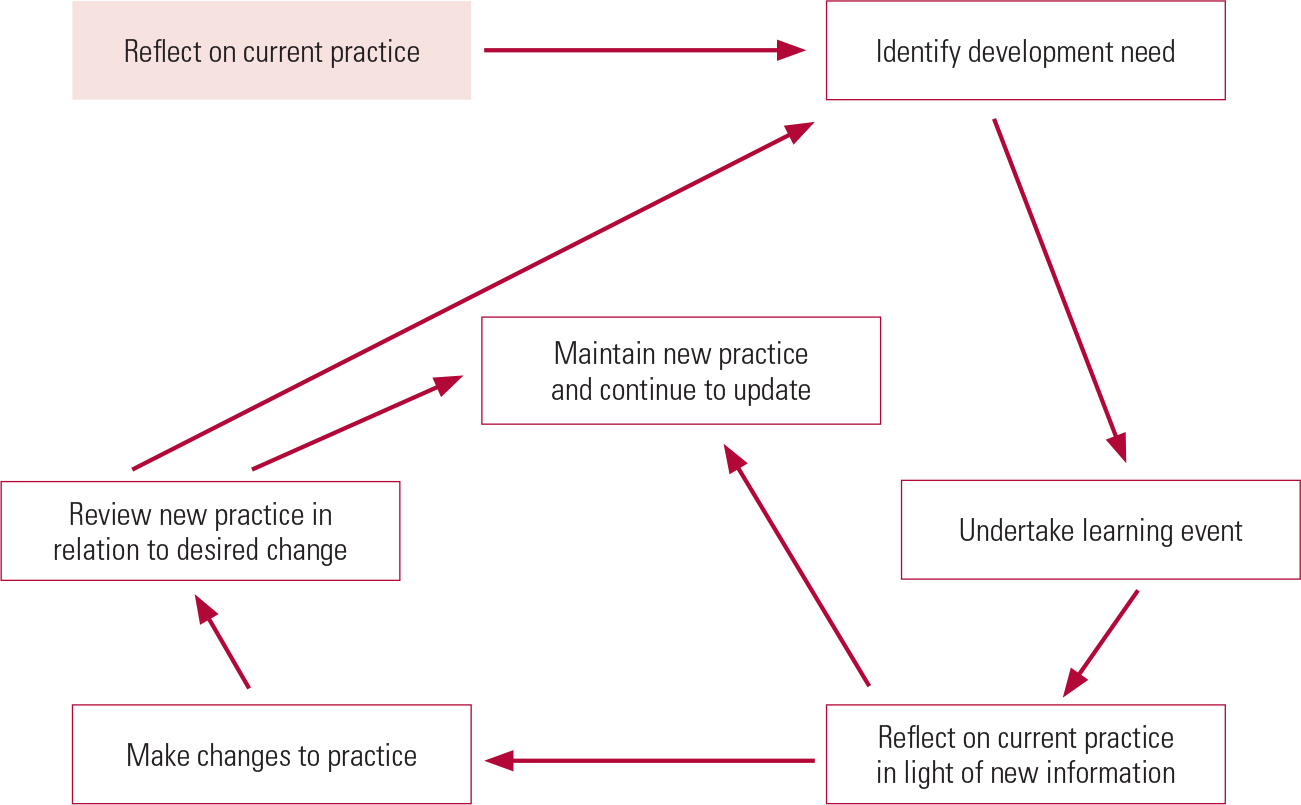

Collating evidence of improvement can be difficult in some circumstances and will be impossible if the initial objective is not specific. Organisations are now collecting more clinically relevant outcome measures (although this is not yet universal) and clinical audit is a useful tool for measuring performance against predetermined standards. In its guidance on revalidation, the College acknowledges the benefit of clinical audit in both identifying the need for improvement and demonstrating that it has taken place (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2014). Showing that learning has been incorporated into practice need not and should not be onerous. Considering learning in relation to clinical practice through, for example, a case-based discussion, is a useful way to gain feedback. If honestly and openly approached, such a process could identify further, previously unconsidered learning as needed. The result, therefore, is one of continued learning, reflection and change (Fig. 2).

FIG 2 The learning cycle.

Reflection as part of effective CPD

In CPD, reflection is the process of thinking about our actions, responses or practice in a conscious, open and considered way in order to learn from them. It encourages us to ask why we do things or make particular decisions and thus whether there are other, better options.

There are two times at which reflection is particularly important in ensuring that CPD improves patient care:

-

when identifying development needs, often in response to feedback, we must review our practice and why we came to a particular decision or work in a certain way;

-

after a learning event, we should consider the new information in relation to our own practice, and decide whether we need to make changes or whether it supports our current approach.

Reflecting on current practice to identify development needs

We need to consider not just what we are doing but why. This often happens after significant events such as a serious incident or a complaint and this is, of course, necessary and good practice. However, if reflection is restricted to such times, consideration of our practice will be restricted and probably unfairly critical. We need to evaluate our practice on an ongoing basis, and to do that we need mechanisms to support us.

-

Reflective practice groups allow teams to consider how they respond in (often) challenging situations and the feelings that patients and situations can evoke.

-

CPD peer groups help the psychiatrist to explore their practice and, from formal or informal feedback, consider which areas could improve through the CPD process.

-

Appraisal considers the whole of a doctor's practice and uses both hard and soft data to support discussion about the care they provide and the relationships they form with patients and colleagues.

-

Case-based discussion and clinical supervision with peers will explore a relatively small area of practice in detail. Although it is not required by the GMC, the College recommends that psychiatrists undertake at least two case-based discussions each year.

-

Review processes should allow doctors and clinical teams to learn from incidents and consider their development needs.

-

The cycle of clinical audit requires considering the findings (comparing practice with established or agreed standards) to develop an action plan for improvement.

Alongside these are many less formal discussions about what they do that clinicians have with colleagues during day-to-day practice.

If they are committed to improvement and learning, any of the above mechanisms will provide the psychiatrist with a rich view of their practice and therefore suggest what their development needs are.

Reflecting on new learning to change practice

Even if new knowledge has been acquired, without changes to practice patients will not experience any benefit. Reflection is the process that bridges the gap between theory and practice. However, changing practice is not necessarily simple. Most psychiatrists work within teams and interact closely with others. Changing an individual's practice might, therefore, not be possible without changing a wider system. It is thus essential, when setting objectives, that not only the needs of the doctor but the needs of the teams and services in which they work are considered.

As when setting development objectives, considering how new learning will affect practice requires space and honest consideration of our own behaviour. Through regular meetings the peer group will allow space for the doctor to consider both their needs and later, through reflection and appropriate challenge, whether they have met their learning objectives.

In practice, some reflection will need to take place in other arenas (such as incident reviews or clinical audit meetings) or by the doctor alone. Achieving meaningful reflection might require practice. As shown in Fig. 1, the Academy of Royal Colleges’ template provides a useful framework for reflection.

What is effective CPD?

Put simply, effective CPD is learning that meets the doctor's developmental needs and leads to improved patient care. Better care does not solely come from improved clinical skills. Teachers and trainers who enhance their educator skills through CPD indirectly improve the care of all the patients their students go on to treat. Similarly, those who use CPD to develop their leadership skills improve patient care provided by the clinicians working in their service.

There are several factors related to learning that make CPD more likely to improve patient care.

-

Learning objectives should be set after honest consideration of the doctor's range of practice and feedback from various sources.

-

Learning that relates to the doctor's work is best suited to improving their practice.

-

Various forms of education should be considered to acquire the learning. This is an important point, as it is always tempting to look for a taught course rather than considering other forms of learning, such as working alongside a colleague. The Royal College of Psychiatrists no longer specifies the need for ‘internal’ and ‘external’ CPD, but the benefit of learning from others in outside organisations should not be underestimated.

-

New knowledge should be considered alongside current practice to identify any changes that are needed.

-

Time must be available to implement any necessary changes.

-

Effects should be evaluated after implementation – has the desired improvement actually been achieved?

Box 2 summarises the principles of effective CPD.

BOX 2 Principles of effective CPD

-

The doctor feels able to honestly and openly discuss their development needs

-

Information about their practice is accurate and readily available

-

There is a supportive environment in which needs can be considered

-

There is space for new learning to be considered alongside current practice

-

Needs and improvements in the doctor's practice are not considered in isolation from the team/service in which they work

-

Changes to practice are evaluated and further learning identified

Who and what is needed to make CPD effective?

The doctor

The GMC (2012) simply states that ‘you are responsible for identifying your CPD needs, planning how these needs should be addressed and undertaking CPD that will support your professional development and practice’. To identify relevant CPD, the doctor needs to consider the available information about their practice and reflect on areas for improvement. This must cover the entirety of practice, both clinical and non-clinical. Without this open and honest reflection, the effect of any subsequent learning will be limited. The doctor is also responsible for reflecting how new learning should be considered alongside current practice and, as far as they are able, for changing practice as appropriate. In both these areas, although the individual doctor is responsible, they should be supported to do this effectively.

To be in good standing with the College for CPD, all clinically active psychiatrists are required to undertake, on average, 30 h of clinical CPD and thus ensure a high standard of care is experienced uniformly by patients.

The CPD peer group

A doctor's peers are a useful asset in identifying development needs and how and when these needs should be met. The College relies on the effective functioning of a peer group when considering whether someone is in good standing for CPD (Box 3). The peer group should ‘support the individual in developing and completing a relevant [PDP] that leads to an improvement in that person's skills or competence and therefore an improvement in care provided to patients’ (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2015: p. 4). In addition, the peer group is responsible for accrediting learning as CPD activity. A learning activity can only be allocated CPD credits if:

-

it is relevant to the psychiatrist's scope of practice (or intended practice)

-

it is of sufficient quality

-

learning has been understood and, through reflection, considered alongside current practice.

BOX 3 Responsibilities of the CPD peer group

The College relies on the CPD peer group to ensure that learning is relevant and incorporated into practice. Peers should choose their peer group; it should not be allocated by employers. The peer group should:

-

help the psychiatrist to honestly reflect on their practice and identify areas for improvement

-

help convert development needs into achievable goals for a PDP

-

help identify how these goals can be met

-

allow the psychiatrist to reflect on how new learning relates to their current practice

-

consider whether the learning has been relevant to the goal and whether appropriate reflection in relation to practice has been achieved (are there further learning needs?)

-

allocate CPD credits to the learning if it has been relevant to practice and followed by appropriate reflection

The peer group is not fulfilling its duty to the psychiatrist if it does not robustly consider these points.

Rather than answer a set of MCQs at the end of this article, I invite you to complete the reflective template in Fig. 3 so that it can be considered for CPD credits by your CPD peer group.

FIG 3 Reflective template for completion and consideration for CPD credits by your peer group after reading this article.

Appraisal

The appraisal process is at the core of revalidation and, thus, the assurance we give to the public that doctors are safe practitioners. It examines the full scope of the doctor's practice and encourages reflection. CPD is one way in which a doctor can demonstrate that they are up to date in their practice and developing the skills required in their work.

During appraisal, information about the doctor's practice is considered and the doctor is required to reflect on it, with a view to developing a PDP. A good appraiser will support reflection in a way that promotes learning and a formative approach. They will also seek to understand how quality or improvement has been demonstrated.

The following information should be used to develop a PDP within the appraisal:

-

information from and reflection on complaints and other forms of patient feedback

-

information from and reflection on incidents relating to the doctor or the service in which they work

-

multisource feedback

-

clinical activity information

-

clinical outcome information (in the form of patient reported outcome measures (PROMs), patient reported experience measures (PREMs), clinician reported outcome measures (CROMs), etc.)

-

reflections on incidents or feedback in other services (but of relevance to the doctor's practice)

-

the PDP agreed with the CPD peer group.

Good appraisal, therefore, will start the cycle by developing a PDP that reflects the doctor's scope of practice and development needs within it and challenges the doctor to reflect on their development and demonstrate ongoing improvement in practice.

Employers

Employers have a responsibility to ensure that their workforce is up to date and working to appropriate standards. CPD is one mechanism for achieving this. The health service is facing unprecedented financial challenges, but effective CPD does not come without sufficient resources. This is not simply an adequate study leave budget (learning is not necessarily met through taught courses), but also allowing doctors the time to reflect on their development needs and the meaning of new knowledge in relation to their own practice, and also to evaluate the impact of any change.

As already mentioned, psychiatrists rarely work in isolation. If the ambition of CPD is to improve patient care, learning in teams is an important option, at least for some people. Therefore, it will be necessary for a whole team, not just a single doctor, to find time for reflection.

Finally, honest and open reflection has been described as a key element to effective CPD. This includes being able to reflect on our actions when things go wrong. Learning from serious incidents is essential to developing safe doctors and safe services and is understandably what the public demands of us. Employers have a major role in providing an environment that is supportive of this approach.

Conclusions

CPD should not be seen as an optional ‘add-on’ to our everyday work and cannot live in conference halls and lecture theatres. It needs to be an integrated part of our everyday practice, with the aim of continually improving the care we provide to patients and their families. It requires us to reflect on our work and behaviour so that we can identify what improvements to make and then consider whether we have achieved them.

Being in good standing with the College for CPD is one way in which we can assure the public that we are maintaining our skills and continuing to develop. It requires the psychiatrist to reflect on their current practice, undertake relevant and effective learning, put that learning into practice and evaluate the outcome. The College relies on the CPD peer group to ensure that learning is relevant and that it is incorporated into practice. To do this requires a constructive, enquiring relationship between peers that can only exist if they are comfortable being open and honest with each other.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.