‘If you want something new, you have to stop doing something old’ – Peter F. Drucker, 1909–2005.

Inherent in the working life of a psychiatrist are difficult decisions. These decisions have consequences for the patient, the treating team and the wider healthcare system. Making the right decision for the patient should of course be the priority. There are, however, numerous factors that can both rightly and wrongly influence these decisions. In fact, it is increasingly recognised that many of these influencing factors encourage doctors to do more – to diagnose more, to investigate more and to treat more (Reference Malhotra, Maughan and AnsellMalhotra 2015). This article is about a new campaign in the UK called Choosing Wisely, which aims to reduce unnecessary interventions by increasing awareness about the overtreatment and overdiagnosis that occur throughout clinical practice (www.choosingwisely.org).

Such overuse is not just a problem for our medical and surgical colleagues; it is also an issue for psychiatrists. A brief examination of the history of psychiatry reveals that psychiatrists have been guilty of both overdiagnosis and overtreatment and that this has had devastating consequences for patients (Reference BurnsBurns 2014). The Choosing Wisely campaign aims to find out which treatments and tests, currently in use, might be unnecessary or even potentially harmful to patients.

Overdiagnosis

The terms overdiagnosis and overtreatment reflect decisions made by doctors that bring no patient benefit. Overdiagnosis occurs when ‘individuals are diagnosed with conditions that will never cause symptoms or death’ (Reference Welch, Schwartz and WoloshinWelch 2011). Reference MoynihanMoynihan (2015) gave the reasons for overdiagnosis as ‘disease definitions […] being broadened, thresholds lowered, and diagnostic processes changed in ways that increase patient populations without rigorous investigation of the potential harms of those changes or proposed systems to mitigate those harms’. In some circumstances, this might be the medicalisation of normal human experiences (Reference Dowrick and FrancesDowrick 2013). In psychiatry, some argue that this has occurred with the removal of the bereavement exclusion from the diagnostic criteria for major depression in DSM-5 (Reference Wakefield and FirstWakefield 2012), although this change aims to improve the recognition of those suffering with major depression during periods of grief.

Awareness of overdiagnosis began in relation to screening programmes for precancerous states. An example of this is the evidence that as many as 1 in 5 women given a diagnosis of breast cancer as a result of screening would likely not have been harmed by that cancer (Reference Moynihan, Glasziou and WoloshinMoynihan 2013). In psychiatry, an example of overdiagnosis could be the recent fourfold rise in autism diagnoses in the USA, which has been mostly attributed to the reclassification of children with neurodevelopmental disorders, rather than a true spike in cases (Reference Polyak, Kubina and GirirajanPolyak 2015). Another area of potential overdiagnosis is misunderstanding the ‘at-risk mental state’ as a diagnosis rather than as a research construct. Evidence suggests that only 1 in 5 with an ‘at-risk mental state’ subsequently develop a psychotic illness (Reference Fusar-Poli, Bonoldi and YungFusar-Poli 2012). A misunderstanding of this classification as simply another diagnosis requiring standard treatment could lead to many in this group being treated inappropriately.

Overdiagnosis is not a one-sided matter. There are many examples where insufficient diagnoses or treatments are being applied. In fact, it is probably the case that most increases in rates of diagnoses arise from the much welcomed increasing awareness of mental health problems and the reduction in stigma that encourages people to present to services. Simon Wessely, the current President of the Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCPsych), frequently mentions in the UK media the unacceptable levels of underdiagnosis and undertreatment of depression (Reference BoselyBosely 2014). Further, the 2015 NHS Atlas of Variation in Healthcare finds a threefold variation across England in the percentage of people who are recorded as having a severe mental illness (Public Health England 2015). Although there are many reasons for this, NHS England concludes that detection needs to improve in some areas (Public Health England 2015). While underdiagnosis is clearly a more pressing issue in mental health nationally, and psychiatrists should certainly support strategies that seek to improve the detection of mental illness, overuse is also a critical problem, even within the context of overall underuse. These processes are not mutually exclusive.

Overtreatment

Overtreatment refers to any of the following (Reference Hoffman and PearsonHoffman 2009):

-

• when treatment brings no benefit to the patient

-

• when there is a lack of evidence to support a treatment

-

• when the harms outweigh the benefits

-

• when a treatment is excessive in complexity, duration or cost, relative to accepted standards.

Examples of overtreatment are widespread. In the USA, where insurance-based health provision dominates and the budget is essentially infinite, the variation in cost of healthcare between different regions suggests that 30% of money spent on healthcare does not bring any patient benefit (Reference Berwick and HackbarthBerwick 2012). Across all healthcare in the UK, studies have suggested that around 20% of clinical work in the National Health Service (NHS) has no effect on outcomes (Reference MacArthur, Phillips and SimpsonMacArthur 2012). No specific data are available about national levels of overtreatment in mental healthcare in the UK, although the NHS Atlas of Variation is beginning to provide evidence of unwarranted variations in clinical practice between regions (Public Health England 2015).

In psychiatry, the reasons for overtreatment are multifactorial. One reason may be an excessive reliance on symptom scores. A recent study found that using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scale for depression significantly increased antidepressant prescription (adjusted OR = 3.80; 95% CI 1.0–13.9) (Reference Jerant, Kravitz and GarciaJerant 2014). A particular problem with screening tools such as the PHQ-9 in the common context of comorbidity with chronic physical conditions is that they can produce spuriously high scores by including physical symptoms of depression, such as fatigue, which may actually be related to the coexisting physical condition. So this can also lead to overdiagnosis.

Overtreatment may also be due to prescribing habits: in 2009 the average dose of flupentixol decanoate depot prescribed in the UK was 60 mg every 2 weeks (NHS 2009); however, a Cochrane review found little evidence for clinical improvement from doses higher than 50 mg every 4 weeks (based on 3 small studies) (Reference Mahapatra, Quraishi, David, Sampson and AdamsMahapatra 2014). Evidence therefore suggests that there is a maximum clinically effective dose that is considerably less than the average prescribed dose in the UK. This is likely to be related to the fact that doses for this medication historically have been far higher (Reference Reed and FanshaweReed 2011).

Another example of overtreatment is the use of antipsychotics in dementia. There is good evidence to suggest that they can cause significant harm (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health 2007). Guidance suggests that antipsychotics should be considered only after non-pharmacological interventions have been unsuccessful, as the benefits of these medications remain uncertain (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health 2007). However, in 2012, a study of over 10 000 patients with dementia found that, of the 1001 patients prescribed antipsychotic treatment for more than 6 months, a quarter had no documented review of therapeutic response in the previous 6 months (Reference Barnes, Banerjee and CollinsBarnes 2012). This indicates a large number of potential cases where antipsychotics have been started but perhaps not stopped following a lack of response.

Since 2002, the BMJ has run a ‘Too Much Medicine’ campaign, with the aim of persuading doctors to become ‘pioneers of de-medicalisation, [by] handing back power to patients, resisting disease mongering, and demanding fairer global distribution of effective treatments’ (Reference Moynihan and SmithMoynihan 2002). The BMJ has published many articles that demonstrate evidence of overdiagnosis and overtreatment. For example, in December 2015, an article in this series discussed the ongoing lack of clarity about whether screening for ovarian cancer actually saves lives (Reference KmietowiczKmietowicz 2015). Few articles in this series relate to mental health. One article raised concerns that marketing strategies of medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder by pharmaceutical companies lead to large rises in their use (Reference McCarthyMcCarthy 2013). Another commented that the recent UK government's ‘name and shame’ Dementia Challenge website might lead general practitioners (GPs) to overdiagnose dementia to avoid appearing on the list (Reference BrunetBrunet 2014).

Reasons for overuse

The reasons for overdiagnosis and overtreatment are complex and multifactorial. There is, however, a clear confluence of influences exerted on the doctor during each consultation. These include the following:

-

• clinical culture: for example, it may be the cultural norm to order excessive and unwarranted baseline tests, such as computed tomography (CT) head scans for all first episodes of psychosis;

-

• time pressures: for example, time constraints do not allow for a thorough history and examination, so more tests are performed to rule out potential conditions;

-

• defensive practices: for example, the doctor orders tests or starts treatments with the primary aim of avoiding litigation, rather than acting for patient benefit;

-

• poor health literacy: for example, a survey of 150 gynaecologists revealed that one-third did not understand the meaning of a 25% risk reduction created by mammography screening; many of them believed that, if all women were screened, 25% fewer women – or 250 fewer out of every 1000 – would die of breast cancer, when actually the best evidence-based estimate is actually only 1 in 2000 fewer (Reference Malhotra, Maughan and AnsellMalhotra 2015);

-

• patient factors: for example, the doctor is aware that a treatment will not be effective, but prescribes it to avoid conflict with the patient; a survey of 200 GPs found that 33% had prescribed an antidepressant simply because the patient had requested it, rather than because of a clinical indication (Mental Health Foundation 2005: p. 8);

-

• pharmaceutical pressures: for example, a doctor is encouraged to prescribe a medication by a pharmaceutical representative despite the fact that evidence does not favour this option.

Why reducing overuse is important

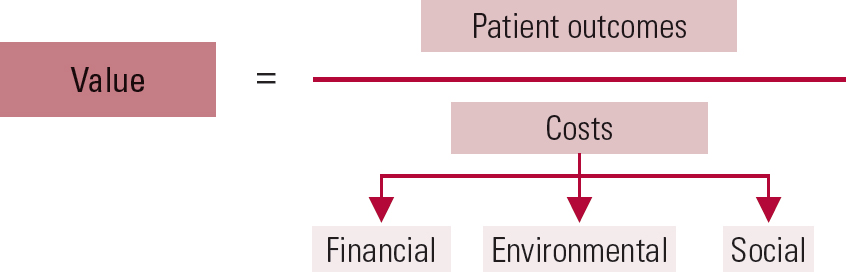

The sustainable provision of high-quality healthcare is fundamental to the health of future generations. Whether a given healthcare service is sustainable is based on what health outcomes can be achieved within the constraints of the system. Importantly, these constraints are not just financial but lie across three domains: financial, environmental and social (Reference Maughan, Lillywhite and CookeMaughan 2016). These three areas are known as the ‘triple bottom line’ of sustainability (Reference SavitzSavitz 2013). In our financially strapped healthcare system, financial costs tend to dominate clinical decisions. However, the environmental and social costs are also highly significant. Healthcare is carbon intensive: the NHS has a larger carbon footprint than some medium-sized European countries (Reference Steen-Olsen, Weinzettel and CranstonSteen-Olsen 2012) and is the largest contributor of greenhouse gas emissions in the public sector in the UK (Sustainable Development Unit 2013). Most of this is made up of clinical factors: in fact, medication is the single largest contributor to the carbon footprint of the NHS (Sustainable Development Unit 2013). The social costs of healthcare are also highly significant. For the patient, an acute psychiatric admission could result in the loss of a job, loss of relationships and possibly even loss of accommodation. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment result in the wasting of clinical resources. Money and carbon are squandered and patients’ lives are unnecessarily disrupted and sometimes harmed (Reference Moynihan, Glasziou and WoloshinMoynihan 2013). This overuse therefore serves to undermine the sustainability of our healthcare system.

The concept of value in healthcare (Fig. 1) has been developed over the past decade as a response to growing awareness of ongoing unnecessary or ineffective clinical practices (Reference GrayGray 2011). High-value interventions have little wasted resource, whereas low- or negative-value interventions are themselves waste. In this case overdiagnosis or overtreatment should be viewed as waste. Value in healthcare refers to the patient outcomes that are achieved per pound spent (Reference PorterPorter 2010). Arguably, however, value should be broadened to refer to the triple bottom line of sustainability.

Fig 1 Value in healthcare – a sustainable approach based on the triple bottom line of financial, environmental and social costs (after Reference Maughan and AnsellMaughan & Ansell, 2014).

The Choosing Wisely programme

In the USA in 2012, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) launched the first Choosing Wisely campaign. It was in response to a growing awareness that doctors were partly responsible for the spiralling costs of healthcare in the country (Reference Wolfson, Santa and SlassWolfson 2014). The campaign involved medical societies proposing a ‘Top Five List’ of tests or treatments that they thought were being overused in their specialty and did not provide meaningful benefit for patients. Since then, medical and surgical specialty societies across the USA have produced more than 70 Choosing Wisely lists, with around 400 recommendations. This campaign was subsequently taken up in Canada, which in 2014 invited several other countries to start their own Choosing Wisely campaigns. Now, more than 15 countries, over several continents, have developed their own campaigns, including, in 2015, the UK, led by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges.

The fundamental premise of the Choosing Wisely campaign is that, by developing their own Top Five List of unnecessary interventions, medical societies will become more aware of the problem of overdiagnosis and overtreatment. The aim is that this increased awareness will make commonplace conversations between doctors and patients about which interventions are truly necessary and will ultimately reduce unnecessary interventions.

Is Choosing Wisely simply about reducing costs?

In 2014, D. M. was co-author of a report published by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges urging doctors to review their clinical decisions with the aim of reducing overtreatment (Reference Maughan and AnsellMaughan 2014). The report stated that ‘If the finite NHS resources are spent on costly interventions that have little benefit, then the service we provide will be of little value and the resources we have will be wasted. The key is to focus on minimising waste in all its forms. By doing this, value, and therefore good health outcomes, is maximised’ (Reference Maughan and AnsellMaughan 2014: p. 6). It argued that, in a healthcare system with a finite set of resources, the issue of reducing unnecessary interventions becomes an ethical one: one doctor's overtreatment is another patient's delay.

Although the Choosing Wisely initiative was initially created in response to the need to cut healthcare spending in the USA, it has been taken up in other countries with a different emphasis. In Canada, the major rationale for their Choosing Wisely campaign is that unnecessary tests and treatments undermine high-quality care ‘by potentially exposing patients to harm, leading to more testing to investigate false positives and contributing to stress for patients’ (Choosing Wisely Canada 2014). In the UK, the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges has been clear that the programme is not about cutting costs or refusing treatments, but about improving the value of care by reducing unnecessary interventions (Reference Malhotra, Maughan and AnsellMalhotra 2015).

Choosing Wisely – the RCPsych programme

In June 2015 the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges requested all medical Royal Colleges to provide a Top Five List of interventions whose use should be questioned. The following guidance was provided for developing the list:

-

• it should be relevant to the specialty

-

• it should have an impact on patients and/or the NHS: the unnecessary intervention should result in an unwanted effect on patients or be a drain on NHS resources

-

• it should be evidence based

-

• Colleges should actively involve patients and the public in drawing up the list

-

• Colleges should prioritise in their recommendation those interventions that would have a big positive impact

-

• the list should be measurable and implementable.

At the RCPsych, we (D. M. & A. J.) led a committee made up of representatives from faculties and divisions as well as patients, carers and experts in evidence-based medicine. The committee initially made 12 suggestions through expert consensus (the options listed in Table 1). A survey constructed using these suggestions was sent to all UK members of the RCPsych in September 2015, asking which options they would choose to be on the Top Five List. Members were asked to make their choice on the basis of which option they thought would have the greatest positive impact on clinical practice. It was made known to members that the results of the survey would not directly determine the final list, but would inform the discussions of the Choosing Wisely committee.

TABLE 1 Results of the RCPsych Choosing Wisely survey

Over 50% of respondents thought that the continued use of antidepressants without adequate response and the long-term use of benzodiazepines should be on the list (Table 1). Results indicated that members thought antipsychotics were being used in circumstances that were inappropriate, such as prescription for children, for adults with dementia and in combination before clozapine treatment is tried. The intervention that received the least support for inclusion was the community treatment order, an intervention that allows legally mandated treatment in the community.

The results of the survey were discussed at a subsequent meeting of the RCPsych Choosing Wisely committee. The Academy of Medical Royal Colleges pared down the lists submitted by its member organisations, and on 24 October 2016 it published 40 recommendations in 11 specialties (see www.choosingwisely.co.uk). The RCPsych's recommendations are shown in Box 1.

BOX 1 The RCPsych Choosing Wisely recommendations

-

1 In the treatment of depression, if an antidepressant has been prescribed within the therapeutic range for 2 months with little or no response, it should be reviewed and changed, or another medication added that will work in parallel with the initial antidepressant.

-

When adults with schizophrenia are introduced to treatment with long-term antipsychotic medication, the benefits and harms of taking oral medication compared with long-acting depot injections should be discussed with all relevant parties.

-

Women who are planning a pregnancy or may be pregnant should not be prescribed valproate for mental disorders except where there is treatment resistance and/or very high-risk clinical situations.

-

When a diagnosis of psychosis is made, CT or MRI head scans should only be used for specific indications where there are signs or symptoms suggestive of neurological problems.

Why is it difficult to create a Top Five List?

Given the complexities involved in making any clinical decision, it was unsurprising that we encountered significant difficulties in creating the RCPsych's original Top Five List. First, there were concerns that if the College made a stand against overuse this might overshadow the substantial problem of underdiagnosis and undertreatment. This is particularly pertinent for psychiatry, where underdiagnosis is potentially greater than in other specialties (Reference BoselyBosely 2014). However, both processes are simultaneously occurring and we agreed that doctors and the public should be made aware of them both.

Second, members raised the point that patients with complex problems are often treated outside of guidelines, as other treatments (within guidelines) are tried but prove ineffective. The concern was that putting interventions on a Top Five List without appropriate caveats could lead to criticism of successful treatment plans for ‘complex patients’.

Third, there were concerns that if the Top Five List was too rigid, it might not allow for the professional autonomy required to make appropriate clinical decisions based not only on the diagnosis, but also on the patient and their circumstances. Nevertheless, while it is important to allow for departures from recommendations, there are certain occasions when the evidence is overwhelmingly against a given intervention. ‘Do not do’ lists provide a forum for discussions about stopping such unnecessary interventions.

Stopping overuse – what works?

Evidence-based medicine has been successful in getting doctors to do new things, through the propagation of best practice. However, an important dialogue has been lacking in the medical profession: that concerning what doctors should stop doing. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines are well respected globally for providing useful information about the evidence and cost-effectiveness of treatments. NICE now runs a very helpful database of ‘do not do recommendations’, which is compiled by lifting ‘do not’ recommendations out of their guidelines.Footnote a The report published by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges argues that doctors should be leading the reduction of wasted resources in healthcare (Reference Maughan and AnsellMaughan 2014). The BMJ's ‘Too Much Medicine’ campaign has also increased awareness at a national level about the concept of overdiagnosis and overtreatment. The Welsh Government has developed a ‘Prudent Healthcare’ campaign aimed at reducing the unnecessary use of clinical resources (www.prudenthealthcare.org.uk). It is unclear whether these initiatives have had a significant impact. This is perhaps because measuring overuse is not easy. The NHS Atlas of Variation has begun this process of measurement, but only a small number of interventions are covered so far (Public Health England 2015). It is our opinion that the (unwarranted) variation across the UK is still largely unknown.

A recent study in the USA (Reference Rosenberg, Agiro and GottliebRosenberg 2015) assessed the effectiveness of the US Choosing Wisely programme. It analysed the trend in the use of seven ‘do not do’ recommendations over the 3 years since their publication in 2012. The study found that the use of two interventions had declined significantly: imaging for headache (from 14.9% to 13.4%; P <0.001) and cardiac imaging (from 10.8% to 9.7%; P <0.001). The use of three interventions did not reduce: preoperative chest x-rays, imaging for low back pain, and antibiotics for acute sinusitis. Two interventions increased in frequency: HPV testing (from 4.8% to 6.0%; P <0.001) and use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (from 14.4% to 16.2%; P <0.001). The authors concluded that additional interventions are required to ensure the successful implementation of Choosing Wisely recommendations, including ‘greater feedback, physician communication training, clinical decision support in electronic medical records, and patient focused strategies’ (Reference Rosenberg, Agiro and GottliebRosenberg 2015). Others have suggested that in order to succeed ‘clinician groups must accept and commit to the Choosing Wisely challenge and […] strategies [should be implemented] that make it easier for clinicians to follow Choosing Wisely recommendations’ (Reference McCarthyMcCarthy 2015).

In our opinion, Choosing Wisely will only ever be effective if patients are involved in the campaign right from the start. This is because there is good evidence to suggest that the concept of shared decision-making is a highly effective strategy for tackling overuse (Reference Mulley, Trimble and ElwynMulley 2012; Reference McCaffery, Jansen and SchererMcCaffery 2016). A Cochrane review of 115 randomised controlled trials found that use of patient ‘decision aids’ improves patients’ knowledge, increases the accuracy of their risk perceptions, improves participation in decision-making and reduces demand for procedures (Reference Stacey, Légaré and ColStacey 2014). There is evidence that skills training for shared decision-making has led to reductions in inappropriate antibiotic use in respiratory infections (Reference Coxeter, Del Mar and McGregorCoxeter 2015) and better understanding of the risk of overdetection in breast screening (Reference Hersch, Barratt and JansenHersch 2015). Fundamental to the success of the Choosing Wisely campaign, therefore, is engaging well with the public and patients.

Conclusions

Stopping overuse is difficult. It requires a broader approach than that required for introducing a new intervention. Instead, a culture shift is required. Top Five Lists aim to provide a weight of professional opinion against certain interventions in order to emphasise the issue of overdiagnosis and overtreatment. Good media attention alongside substantial patient and public involvement will be needed. Ideally, the public will view Choosing Wisely as an approved and accepted ‘brand’ of sensible clinical practice. But, most importantly, for the campaign to succeed, shared decision-making must become the new mantra of medicine.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Overdiagnosis is:

-

a diagnosing too many conditions in one patient

-

b having too many different diagnoses to choose from

-

c diagnosing an illness that will never cause symptoms or death

-

d diagnosing the wrong condition in patients

-

e overtreating patients.

-

-

2 Which of the following does not describe overtreatment?

-

a When treatment brings no benefit to the patient

-

b When a treatment harms the patient

-

c When there is a lack of evidence to support a treatment

-

d When a treatment is excessive in complexity relative to accepted standards

-

e When a treatment is excessive in duration or cost relative to accepted standards.

-

-

3 The triple bottom line of sustainability is:

-

a financial, environmental and social

-

b value, quality and efficiency

-

c financial, social and technical

-

d quality, safety and compassion

-

e safety, quality and probity.

-

-

4 Value in healthcare refers to:

-

a the personal values that doctors have

-

b the personal values of patients

-

c the financial value of a service

-

d the health outcomes achieved per pound spent

-

e better investment in healthcare.

-

-

5 Choosing Wisely is:

-

a a campaign to improve the wisdom of doctors

-

b a campaign to increase awareness about overdiagnosis and overtreatment

-

c a campaign aimed at medical students to help with their career choice

-

d a government campaign aimed at reducing costs

-

e a way to get doctors to prescribe more medication.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | c | 2 | b | 3 | a | 4 | d | 5 | b |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.