The diagnostic process can aid understanding of complex and distressing psychiatric symptoms offer a shared language with clinicians, family, friends and others (e.g. employers); validate distress; support access and shared decision-making regarding care and treatment; and guide thinking and discussion about prognosis and recovery (Hayne Reference Hayne2003; Pitt Reference Pitt, Kilbride and Welford2009). However, this process can also feel reductive, stigmatising and/or meaningless to patients and can dominate an individual's sense of identity (Stalker Reference Stalker, Ferguson and Barclay2005; Horn Reference Horn, Johnstone and Brooke2007; Pitt Reference Pitt, Kilbride and Welford2009; Proudfoot Reference Proudfoot, Parker and Benoit2009; Hagen Reference Hagen and Nixon2011). Findings suggest that shared decision-making, associated with diagnosis and extending to decisions about care and treatment, is likely to enable people to have greater agency in their use of mental health services (Milton Reference Milton and Mullan2015). This is likely to support a better relationship with services and increased hope and recovery (Pitt Reference Pitt, Kilbride and Welford2009; Bilderbeck Reference Bilderbeck, Saunders and Price2014; McCormack Reference McCormack and Thomson2017). Contrastingly, the experience of exclusion from the decision-making process and subsequent clinical application of a diagnosis can leave patients feeling dismissed, unimportant and stigmatised (Pitt Reference Pitt, Kilbride and Welford2009; Bilderbeck Reference Bilderbeck, Saunders and Price2014; Lovell Reference Lovell and Hardy2014), which may undermine hope and impede recovery.

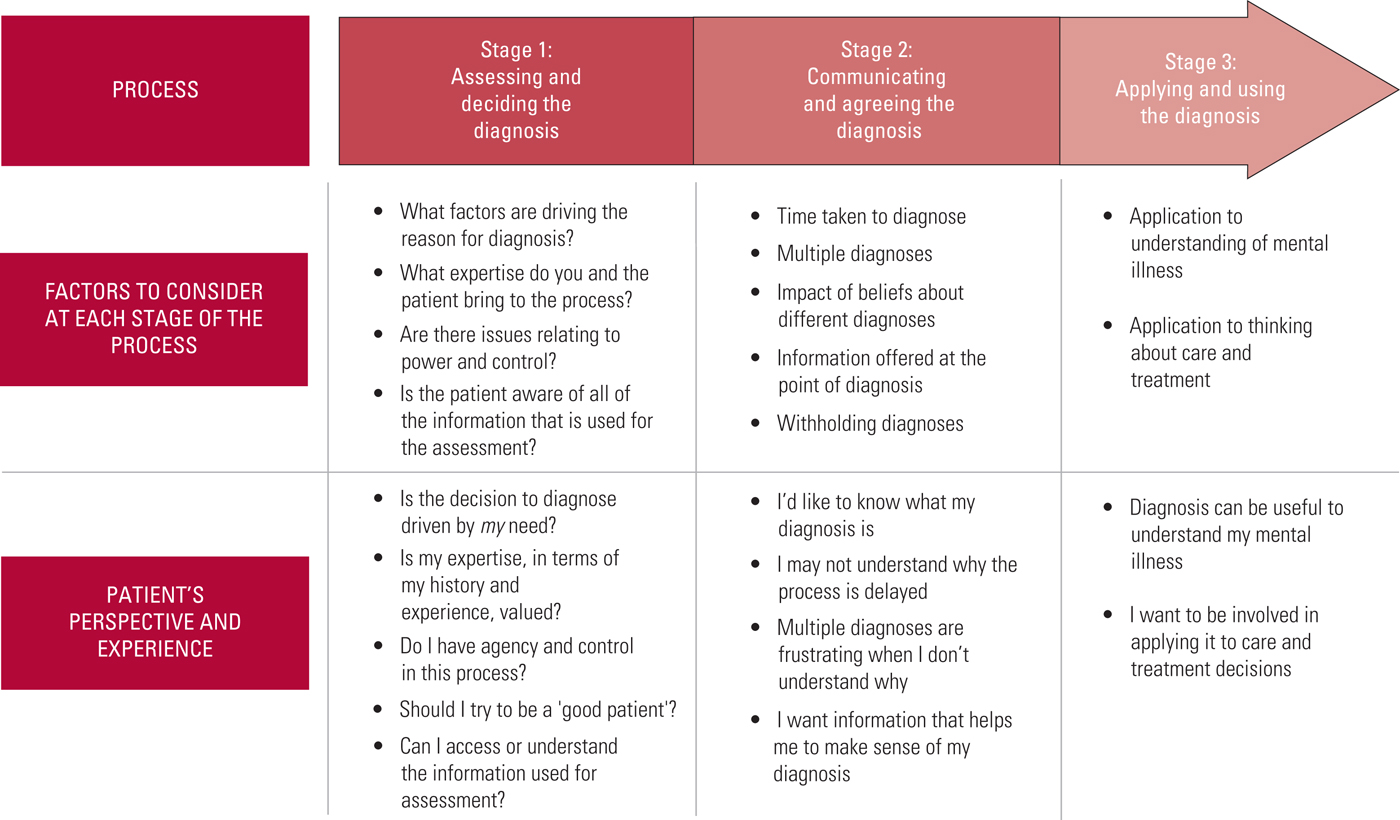

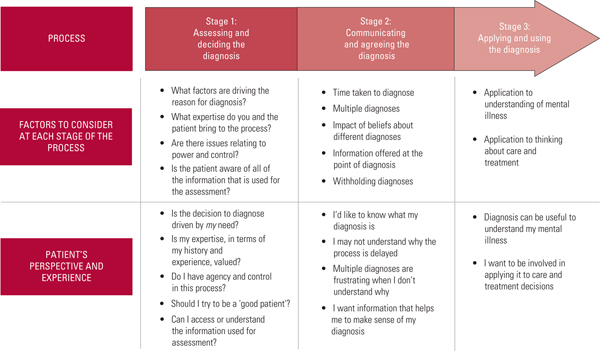

We previously explored the diagnostic journey from the perspectives of patients and clinicians (Perkins Reference Perkins, Ridler and Browes2018). This gave us an understanding of the complexities and potential inconsistencies between the perspectives of clinicians and the views and preferences of patients. We have also worked in collaboration with the World Health Organization, seeking patient feedback on the proposed content for ICD-11 (Hackmann Reference Hackmann, Green and Notley2017). Despite indications that a collaborative approach may be beneficial, there is a lack of operational clarity about what this might involve in clinical practice. In this article we discuss the three stages of the diagnostic process as identified from our previous work: (1) assessing and deciding the diagnosis, (2) communicating and agreeing the diagnosis and (3) clinically applying and using the diagnosis (Fig. 1).

FIG 1 Potential considerations and patient perspectives at each stage of the diagnostic process.

We recognise that the diagnostic process is heavily shaped by clinical environments and contexts that are not predictable. Consequently, the diagnostic process may often be disjointed and subject to factors that may undermine meaningful collaboration and the continuity of care that is required to facilitate this (e.g. complex emergencies where there is clinical pressure to diagnose quickly and decisively and settings with multiple agencies and limited service integration or resource). The aim of this article is not to offer a blueprint or gold standard for the diagnostic process but rather to facilitate reflection and offer guidance for clinical practice within complex clinical systems.

Stage 1: assessing and deciding the diagnosis

Drivers of diagnosis

There may be multiple drivers for patients and clinicians to enter a diagnostic process. Patients often enter mental health services seeking treatment, support or care and may perceive the clinician as gatekeeper to these services. Clinicians, on the other hand, tend to feel responsible for providing services and are subject to multiple systemic, professional and legal pressures. These starting positions will explicitly and implicitly influence motivations, reasoning and expectations when embarking on a diagnostic process. Findings suggest that if patients feel that a diagnostic process is driven by their needs (e.g. to gain access to care, treatment or support) as opposed to service drivers (e.g. to complete paperwork) or political drivers (e.g. for billing purposes) this contributes to the process being perceived as useful and informative (Frese Reference Frese and Myrick2010). Clinicians hold certain legal and clinical responsibilities and there may be situations where they judge that these demands override the need to ensure that patients are informed and involved in decision-making (e.g. in acute situations, where an emergency response is required). In these instances, it is important to consider if and when the patient can be involved in decision-making, challenge clinical assumptions that may unnecessarily undermine the patient's agency, use careful clinical judgement, and ensure that there is always an explicit clinical and ethical rationale for making the decision not to involve the patient (and that this has been recorded).

Regardless of the drivers, both clinician and patient bring expertise to the diagnostic process. The clinician is a learned expert, with training, clinical experience and medical authority. The patient is an expert in their own history, mental illness and, possibly, mental health service use and treatment. In most cases the patient will have a degree of mental health literacy and many clinicians will themselves have lived experience of mental illness. A collaborative and reciprocal diagnostic process draws on, and integrates, expertise by learning and expertise by experience. Contrastingly, in non-collaborative practice, patients have reported that they often feel that their expertise is undervalued, an experience that has been associated with an imbalance of power resulting in learned helplessness and passivity (Memon Reference Memon, Taylor and Mohebati2016). There have been reports of clinicians not taking on board patients' subjective accounts of lived experience, causing one author (Hagen Reference Hagen and Nixon2011: p. 54) to reflect that clinicians wanted patients to be ‘seen but not heard’. Additionally, a non-collaborative process, where patients feel unable to question the diagnosis, has been described as holding the clinician in the expert ‘knowing’ position while the patient is reduced to a position of ‘not knowing’ (Horn Reference Horn, Johnstone and Brooke2007).

The power imbalance

As suggested, the roles of patient as ‘service seeker’ and clinician as ‘service provider’ may result in a power dynamic between the clinician and the patient that can create a barrier to shared decision-making. From the patient's perspective, the clinician traditionally has a certain degree of power over them (Henderson Reference Henderson2003). For psychiatrists specifically, this may be due to their perceived status and authority and the dominance of the ‘biomedical/legal model’ (Behuniak Reference Behuniak2010), which has been associated with disempowerment in the diagnostic process (Pitt Reference Pitt, Kilbride and Welford2009). An imbalanced power dynamic in healthcare settings can undermine patients' confidence to communicate or participate in treatment decisions. This can be due to a desire to adopt the role of the ‘good patient’ – a role that is characterised by passivity and compliance (Hagen Reference Hagen and Nixon2011; Bilderbeck Reference Bilderbeck, Saunders and Price2014; Joseph-Williams Reference Joseph-Williams, Edwards and Elwyn2014). Our work suggests that a shared and reciprocal diagnostic process could facilitate a more nutrient form of power (May Reference May1998; Behuniak Reference Behuniak2010), which can be shared between patient and clinician to mutual benefit.

Gathering and sharing information

Findings from patients suggest that it is important for clinicians to explain their thinking, pace the diagnostic process, and make time for questions and assimilation (Bilderbeck Reference Bilderbeck, Saunders and Price2014; Milton Reference Milton and Mullan2015). Many sources of information that are used to aid decision-making during assessment may be inaccessible or difficult for patients to understand. This includes input from other members of the mental health team, information from medical records, classification systems (e.g. the ICD or DSM) and technical or medicalised language. Inaccessibility to these sources could diminish the patient's role and agency in the diagnostic process.

Classification systems are useful tools for guiding diagnostic decision-making and, with some explanation and ‘decoding’ of medical or technical language (e.g. terms like ‘retardation’, ‘neurovegetative’ and ‘word salad’), could be beneficial as a shared resource. Efforts to enhance reliability have resulted in systems that encourage practitioners to focus on operational symptoms and ‘taxonomy’ of mental ill health over internal or ‘felt’ phenomena. Additionally, psychiatry has been criticised for adhering to a reductionist approach that struggles to take a holistic perspective of mental illness (Engel Reference Engel2012). Arguably, this medical context has tended to disregard the patient's expertise in their own physiological, emotional, psychological and social experience and explanations, and this may result in defaulting to a more limited exploration of the patient's history and their lived and felt experience. A collaborative process will naturally and explicitly value the information that patients bring alongside the critical learning and clinical experience of the clinician and wider multidisciplinary team. It will also ensure that patients understand that the information used to aid decision-making comes from many sources and that medical knowledge can help to contextualise their experiences. This should protect against disengagement from the process as a result of feeling uninvolved and devalued. In fact, findings suggest that a collaborative relationship between patient and clinician often is experienced as supportive, validating and caring (Bilderbeck Reference Bilderbeck, Saunders and Price2014), which is likely to facilitate a therapeutic relationship.

Box 1 outlines suggestions for ensuring a collaborative diagnosis during stage 1 of the diagnostic process.

BOX 1 Suggestions for a collaborative diagnosis during stage 1

Stage 1: assessing and deciding the diagnosis

• Consider your and the patient's reasons for entering a diagnostic process. Discuss and consider whether:

○ the patient has thought about this

○ this is driven for both of you by the patient's need

• Discuss whether the patient would find a diagnosis helpful. Explain and consider the following:

○ it may make sense of and explain their mental illness

○ it may offer a shared language for friends, family and others

○ it may guide decision-making in terms of treatment

○ it may support discussion relating to prognosis and recovery

• Make sure you have offered and informed the choice not to undergo the diagnostic process, considering the following:

○ it can feel reductive

○ it has limited explanatory power

○ it can have a negative effect on sense of self and identity

○ it can be feel socially stigmatising

• Make time to weigh up the pros and cons with the patient

• Explicitly value the patient's expertise and their lived experience

○ make appointments long enough to allow for discussion and active listening

○ make explicit links between their lived experience and your diagnostic reasoning

○ invite the patient to question and challenge your reasoning

○ share and decode the language in diagnostic guides (e.g. DSM and ICD)

○ considering offering an informed choice of diagnoses and ask what most resonates with lived experience

• Be aware of power dynamics

○ this could be sensitively acknowledged and discussed with the patient

• Explain that the process of diagnosis can be protracted and may involve a period of uncertainty, e.g. waiting to see what symptoms emerge

Stage 2: communicating and agreeing the diagnosis

Delay and uncertainty

The amount of time taken to reach a diagnosis has been found to be important to patients, and patients have reported relief at getting a diagnosis after a long delay (Proudfoot Reference Proudfoot, Parker and Benoit2009). One reason for delay may be difficulty reaching a diagnosis that feels accurate (e.g. Outram Reference Outram, Harris and Kelly2014). In this instance, a drawn-out and robust assessment period is likely to benefit patients, as findings suggest that receiving several potential diagnoses can be distressing, unhelpful and frustrating (Frese Reference Frese and Myrick2010; Hagen Reference Hagen and Nixon2011). This is especially the case when the patient feels that the diagnosis has been ‘stamped on’ them rather than agreed (Hagen Reference Hagen and Nixon2011: p. 52). An open and transparent diagnostic process should enable patients to understand that the reasons for delay are often that clinicians are attempting to achieve an end result that is satisfactory and useful. Regardless of a robust assessment, however, there may be difficulty achieving a transparent process for a variety of reasons, including unintegrated mental health services involving multiple agents with limited resource to support continuity of care. In addition, psychiatric symptoms can change. Consequently, it should be agreed that a diagnosis is often not a ‘static’ label but a ‘best-fit’ concept and there should be ongoing flexibility to question and alter diagnoses together.

Withholding a diagnosis

Another common reason for delay, or even withholding a diagnosis from a patient, is that the clinician is concerned about discussing the diagnosis with the patient. We believe that the diagnostic process should be collaborative regardless of the diagnosis reached. Research suggests that delaying or avoiding disclosure is more common for diagnoses that have been linked to stigma or are perceived to have a worse prognosis (e.g. schizophrenia and personality disorder) (Clafferty Reference Clafferty, McCabe and Brown2001; Outram Reference Outram, Harris and Kelly2014; Rumpza Reference Rumpza2015). Clinicians have also reported withholding a schizophrenia diagnosis for fear that it may cause distress or be incorrect (Outram Reference Outram, Harris and Kelly2014). Findings suggest that patients do perceive that specific diagnoses (e.g. schizophrenia or other psychoses) hold more stigma and this can lead to rejection of the diagnosis (Frese Reference Frese and Myrick2010). Despite this, a withheld diagnosis can cause patients to feel isolated, confused or insignificant (Bilderbeck Reference Bilderbeck, Saunders and Price2014). Additionally, findings suggest that patients tend to prefer that, if the clinician has reached a diagnosis, it is not withheld, especially if it has explanatory power for them in explaining their symptoms (Bilderbeck Reference Bilderbeck, Saunders and Price2014; Loughland Reference Loughland, Cheng and Harris2015). This includes diagnoses that may be more likely to be withheld by clinicians and may be more likely to be rejected by patients, such as schizophrenia (Loughland Reference Loughland, Cheng and Harris2015) and personality disorder (Bilderbeck Reference Bilderbeck, Saunders and Price2014). Therefore, it is important for clinicians to reflect on their reasoning for reaching a diagnosis but withholding it from the patient. Is the diagnosis necessary? If it is, it is important to challenge any reasoning related to why it should not be shared and collaborative. Patients' concerns about stigma and prognosis are likely to be better addressed by person-centred discussion, which normalises mental illness and considers treatment options or management techniques and supports recovery, than by avoidance of disclosure.

Clarifying the diagnosis

Discussing diagnostic labels can be distressing for patients and it is important to consider what information is available at the time of reaching a diagnosis (Saver Reference Saver, Van-Nguyen and Keppel2007). Information about the diagnosis that resonates with the patient's life experiences and offers some explanation of their symptoms has been found to be beneficial (Milton Reference Milton and Mullan2015; Delmas Reference Delmas, Proudfoot and Parker2012). Despite this, patients have reported that it can be difficult to get access to useful information (Loughland Reference Loughland, Cheng and Harris2015), and this can be experienced as dismissive (Bilderbeck Reference Bilderbeck, Saunders and Price2014). A collaborative diagnostic process will naturally include an information exchange throughout the entire process, including at the time of reaching a diagnosis. It may be beneficial to consider offering or signposting to additional sources of information (such as leaflets and websites) that patients could use to educate themselves further.

Suggestions for engaging in a collaborative diagnosis during stage 2 are offered in Box 2.

BOX 2 Suggestions for a collaborative diagnosis during stage 2

Stage 2: communicating and agreeing the diagnosis

• If the person already has a diagnosis, explain your reasons for thinking together about an alternative diagnosis

• Be sensitive to distress when suggesting a particular diagnosis

• Make time to ensure that the patient understands what the suggested diagnosis is and make time for questions about it

• Invite the patient to challenge or disagree with a suggested diagnosis:

○ ask whether it resonates with their lived experience

• Ask about the patient's perspective on the suggested diagnosis and consider discussing the impact this has on their sense of identity

• Be prepared to answer questions relating to prognosis and discuss the limitations of diagnosis with reference to this

• If you are tempted to withhold a diagnosis, challenge your reasoning for this and consider not formalising the diagnosis (e.g. in medical notes) until it can be discussed with the patient

• Explain that symptoms and diagnoses can change over time

Stage 3: applying and using the diagnosis

Naming the problem

Evidence suggests that patients often want to find an explanation for their mental health difficulties and that the diagnostic process can contribute to this (Bilderbeck Reference Bilderbeck, Saunders and Price2014; McCormack Reference McCormack and Thomson2017). A process that is broader than the categorisation of symptoms, contextualising diagnostic reasoning explicitly with reference to social, psychological and biological factors will have a greater explanatory power (McCormack Reference McCormack and Thomson2017). The diagnostic process can also offer a shared language that reflects this explanation. Pitt et al (Reference Pitt, Kilbride and Welford2009) helpfully differentiate between ‘naming the problem’ and ‘labelling the person’ (p. 419), implying that the process of ‘naming’ offers a shared framework or language with the patient, whereas ‘labelling’ is more associated with stigma. It is important that the resulting explanation feels valid and meaningful to patients, since a diagnostic process that resonates with lived experience has been found to have a positive influence on identity, in addition to aiding understanding (McCormack Reference McCormack and Thomson2017). In contrast, feelings of powerless have been associated with a diagnostic process that prevents patients from developing their own interpretations of their distress (Bonnington Reference Outram, Harris and Kelly2014) and that fails to take a holistic biopsychosocial approach (Lampe Reference Lampe, Shadbolt and Starcevic2012).

The value of knowledge

It has been argued that the ‘knowledge’ or explanatory power discussed above is only helpful to patients if they understand it and can apply it to decisions about care, treatment or recovery (Hayne Reference Hayne2003; Horn Reference Horn, Johnstone and Brooke2007; McCormack Reference McCormack and Thomson2017). Additionally, a diagnosis that has explanatory power can offer insight into managing mental illness in ways that feel personally efficacious (Bonnington Reference Bonnington and Rose2014). Clinicians who do not perceive that patients are able to be actively involved in this process have been described as ‘paternalistic’ and this has been associated with diminishing the autonomy of patients in decisions about their care and treatment (Barker Reference Barker1994). In contrast, a collaborative diagnostic process that involves discussion of how the diagnosis may relate to decisions about care and treatment should foster agency and control for the patient. Beyond supporting decision-making, patients have also reported that they find diagnosis beneficial when it facilitates access to treatment, care and support (Pitt Reference Pitt, Kilbride and Welford2009; Delmas Reference Delmas, Proudfoot and Parker2012).

Box 3 gives suggestions for ensuring a collaborative diagnosis during stage 3.

BOX 3 Suggestions for a collaborative diagnosis during stage 3

Stage 3: applying and using the diagnosis

• Investigate whether the patient feels that the diagnosis helps them to make sense of their mental illness

○ Think with the patient about how they relate their diagnosis to their history, symptoms and lived experience

• Think with the patient about how the diagnosis may inform decisions regarding treatment

○ Make sure they are involved in making these decisions

• Discuss where the diagnosis fits in a wider recovery journey

• Discuss whether the patient has beliefs about the diagnosis that might undermine their hope and recovery

• Make a follow-up appointment to discuss further questions that may have arisen following the diagnosis

• Consider whether to involve the team in supporting the process of assimilation of the diagnosis

Is the diagnostic process person-centred, shared and equitable?

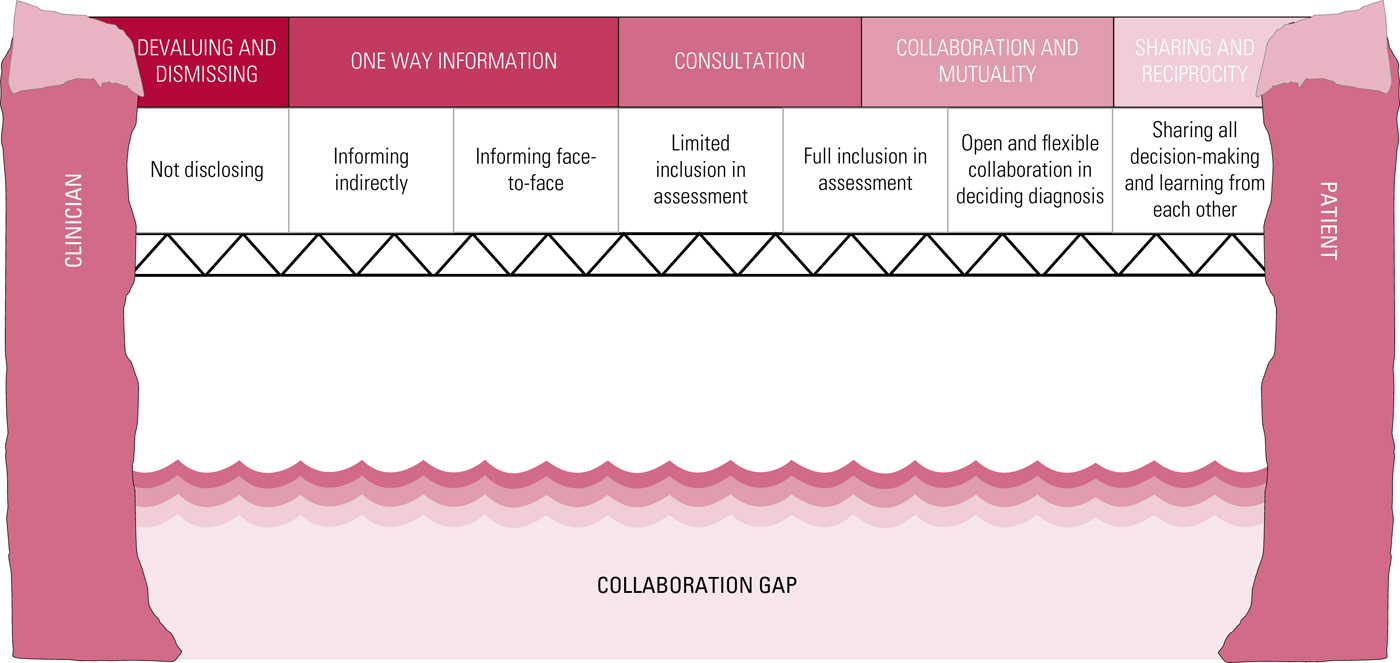

There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution to collaboration and sharing. By its nature it is person-centred and will need to be adapted to the individual needs of each patient. It will also have to flex to operate within often complex and demanding clinical contexts. Adaptation of collaborative decision-making to complex and pressured clinical environments will require clinical judgement but it may be helpful to hold certain questions in mind to support this. At each stage, clinicians should ask themselves, where possible, whether the diagnostic process is:

• person-centred (i.e. explicitly aware of, and attending to, the needs of the individual)

• shared (i.e. truly collaborative and valuing of the expertise that both the clinician and the patient bring)

• equitable (i.e. aware of issues relating to the power imbalance and attempting to overcome these and aspire to a relationship defined by mutuality and reciprocity).

Figure 2 represents the potential levels of a ‘collaboration bridge' between clinician and patient. Reaching the level of sharing and reciprocity enable the collaboration gap to be bridged.

FIG 2 Bridging the collaboration gap between clinician and patient.

Case vignette

Emma presents in Dr A's clinic saying that she took an overdose the night before and that the people at the hospital said that she has an ‘emotionally unstable’ or ‘borderline’ personality disorder. She is not happy with this as she believes that she took the overdose because she felt depressed.

Dr A asks her what she already knows or understands about the diagnosis. She says that she has a friend with this diagnosis and they are not at all similar. Her friend uses drink and drugs but Emma does not. Dr A asks her what diagnosis she believes would fit and she says that her family think that she has ‘bipolar disorder’.

Dr A asks her whether she would like to consider these diagnoses and possibly others too. She is happy to do that and so the doctor explains the broad and specific criteria for both bipolar and borderline personality disorder, translating terms (e.g. ‘disturbances in self-image’) when needed. He highlights the differences between the two diagnoses using his clinical experience to guide the conversation but also drawing on Emma's experience, for example asking about her fluctuations in mood, how rapid they are and what may trigger them and asking her to link these to the two diagnoses. He also touch on other diagnoses that resonate with themes that she has mentioned and clearly experiences, such as depression and anxiety.

Having described the features and related these to Emma's day-to-day experiences, Dr A asks her which diagnosis seems to fit best. Dr A explains that this is important because it guides choice of the best-evidenced treatments. Emma reflects that her changes in mood are very brittle and overwhelming and she strongly identifies with struggling to think of the consequences before acting. She also identifies difficulties maintaining relationships. Emma decides that a diagnosis of ‘emotionally unstable personality disorder, borderline subtype’ seems to fit. However, she is worried about what this might mean for her life in the future and Dr A decides to think about how she might tackle this and what additional support she might need.

He asks Emma to research the proposed diagnosis, suggesting user-friendly websites, and to discuss it with her family and friends if she feels able. They agree to meet again in a few weeks to discuss the diagnoses further and agree a treatment plan. She says that she will carry out some research and plans to bring some of her family to the next appointment.

When they meet in a few weeks, Emma has considered these diagnoses and her family strongly identify with the concept of her having a borderline personality disorder. Together, Dr A and Emma again run through each of the diagnostic criteria against Emma's experience so that they are all clear that she meets the necessary number of items for the diagnosis. Emma then describes the relief she feels at finally understanding why her relationships seem to keep going wrong and states that she is determined to better understand herself and learn to manage her feelings differently. Dr A begins to discuss potential treatment and support options (e.g. peer support, psychological therapy and psychoeducational groups) and talks about how the wider mental health team will be engaged in this process.

What if there is a disagreement between clinician and patient?

In the fictitious case vignette outlined above, a collaborative process reduces the likelihood of clashing perspectives between the clinician and patient. There may be instances where, despite collaboration, differences in opinion persist. In such circumstances, the clinician should try to understand the patient's reasons for objecting to, or preferring, a particular diagnosis. In the example above, Emma may feel that a diagnosis of bipolar disorder is less associated with social stigma. It is also worth exploring the clinical utility of the diagnosis together. If the clinician decides to record a diagnosis that the patient does not agree with, this must be documented and explained to the patient (with the patient's preferred option also documented). Meaningful involvement in care and treatment is a human rights matter and it is important that clinicians carefully consider their reasons for making decisions that patients do not agree with. On one hand, it is the patient's diagnosis; it will affect their understanding of their mental illness, their treatment, possibly their identity and, critically, should be useful or, at the very least, understood by them. On the other hand, clinicians are subject to legal and clinical responsibilities and may feel that it is their professional duty to record a diagnosis that is the most valid in order to best inform decisions regarding care and treatment. These are complex issues but it is important to remain patient-centred and document the decision-making process, including the patient's perspective.

Conclusions

For patients the diagnostic process is far more than a simple classification of their symptoms. Findings show that a diagnostic process and subsequent diagnosis that is not collaborative can feel reductive, labelling and stigmatising and patients have reported that the process can feel dismissive and devaluing. This could undermine hope, recovery and relationships with services. In contrast, findings suggest that a shared and collaborative process, which values the expertise of the patient in terms of their history and lived experience, and contextualises the diagnosis clearly within these factors, can be insightful, meaningful and beneficial for patients. The resulting shared diagnostic label is more likely to resonate with lived experience, have explanatory power and may offer a shared language for friends, family and mental health practitioners. The experience of being listened to and heard has been described by patients as validating and supportive. There are therefore the additional benefits, for both clinician and patient, of supporting engagement and developing a therapeutic relationship. Involvement in the process of thinking about how the diagnosis relates to decision-making regarding care and treatment should foster in the patient hope and a sense of control and agency, thus supporting the recovery process. Moreover, a collaborative diagnostic process will help to identify whether the patient actually needs or wants a diagnosis and whether it might in fact be unnecessary and unhelpful.

A shared diagnostic process is inevitably complex and time-consuming and it is important to consider potential barriers to collaboration. These may include pre-existing beliefs and attitudes, political, professional and systemic pressures, and issues relating to power and control. A collaborative diagnostic process may help patients overcome some of the potential self-stigma by contextualising, explaining and normalising their experiences. However, many diagnostic labels themselves carry stigma or can lead to social exclusion (Pitt Reference Pitt, Kilbride and Welford2009), which cannot be mitigated by the diagnostic process.

This article aimed to explore the patient's experiences of the diagnostic process and the benefits of a shared and collaborative process. We have attempted to draw on research findings and our own experience to inform a framework for supporting a diagnostic process that is person-centred, equitable and shared, so that both the process and output are holistic, useful and empowering for the patient. Just as the disability rights movement has understood the importance of including the voices of patients at all levels, so our work is animated by the philosophy that those living with mental health difficulties are not ‘other’ and there should be nothing written or studied ‘about us, without us’. Moreover, a mutual and reciprocal relationship that honours the expertise, position and potential for learning on both sides leads to improved services and outcomes for all.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust (NSFT) Frank Curtis Library and research manager Bonnie Teague for the advice and support generously given. We also express our gratitude to Alpa Kadchha (research assistant psychologist) and Tallulah Smith (research administrator) for their help, including with developing and formatting the figures in this article.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 From the perspective of patients, which of the following is not listed as a potential reason for patients to seek a diagnosis?

a to gain access to treatment or support

b to understand their symptoms

c to achieve an ICD code to put on paperwork

d to have an explanation to share with friends or family

e to validate their problems or distress.

2 Which of the following is outlined as a potential consequence of a collaborative diagnostic process for patients?

a they feel labelled

b they feel devalued

c they feel dismissed

d they feel frustrated

e they feel valued.

3 What should clinicians keep in mind when communicating a diagnosis to the patient?

a a psychiatric diagnosis is a ‘static label’ that should never change

b it is beneficial to consider offering or signposting to additional sources of information for patients to educate themselves further

c a poor prognosis or potential for stigma are reasonable justifications for withholding a diagnosis from the patient

d receiving several diagnoses is helpful and empowering for patients

e it is best to communicate the diagnosis using technical and medical terms.

4 For the patient, which of the following is not a likely result of the power imbalance between doctor and patient?

a feelings of being seen but not heard

b learned helplessness

c passivity

d a better understanding of their mental health difficulties

e a position of ‘not knowing’.

5 Which of the following is not a component of the ‘collaboration bridge’?

a consultation

b one-way information

c engagement

d collaboration and mutuality

e sharing and reciprocity.

MCQ answers

1 c 2 e 3 b 4 d 5 c

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.