LEARNING OBJECTIVES:

After reading this article you will be able to:

• make a comprehensive assessment of hypersexual disorders

• describe the current nosological status of this disorder

• understand the currently available treatment options.

Compulsive behaviours or impulse control disorders such as gambling are now widely recognised (Dhuffar Reference Dhuffar and Griffiths2016), but hypersexuality remains a controversial symptom or sign. In DSM-5 hypersexuality is defined as ‘a stronger than usual urge to have sexual activity’ (American Psychiatric Association 2013: p. 823). In ICD-10 (World Health Organization 1992) it is termed ‘excessive sexual drive’ (F52.7) and subdivided into nymphomania and satyriasis, which may be defined as uncontrollable or excessive sexual desire in women and in men respectively. Various terms are used for this behaviour, such as compulsive sexual disorder, hypersexuality, hypersexual disorder, sexual or sex addiction and Don Juanism, and we use them interchangeably. A particular problem in diagnosis is whether hypersexuality is one of the symptoms of a mental disorder or a condition in itself.

Epidemiology

There is limited literature on the epidemiology of hypersexuality. However, based on older literature, the prevalence of compulsive sexual behaviour is estimated to be 3–6% (Walton Reference Walton, Cantor and Bhullar2017). In a survey of 1837 Danish university students, prevalence of compulsive sexual behaviour was reported to be 3% among men and 1.2% among women (Odlaug Reference Odlaug, Lust and Schreiber2013). A study involving 1913 Swedish young adults reported internet sexual addiction in 2% of women and 5% of men (Ross Reference Ross, Mansson and Daneback2012). Evaluating the prevalence of hypersexual disorder is difficult as study participants may feel embarrassed to report their behaviour (Derbyshire Reference Derbyshire and Grant2015). Hypersexuality has been a controversial issue but some individuals do seek professional help. However, men are more likely to seek help than women (Dhuffar Reference Dhuffar and Griffiths2016). Dhuffar & Griffiths (Reference Dhuffar and Griffiths2016) found four main barriers explaining women's reluctance to seek help for sex addiction in the UK. They are: (a) individual barriers such as denial and deliberately not wanting to seek treatment; (b) social barriers such as social undesirability and the attitudes of family, parents and peers; (c) research barriers such as lack of universal agreement regarding sexual addiction and limited research into sexual addiction in females; and (d) treatment barriers such as lack of specialist services for the treatment of sexual addiction. However, in 2020, the case of a woman with hypersexuality was reported in a sexually conservative country (Bangladesh) (Arafat Reference Arafat and Kar2020), which seems to suggest that there is more widespread awareness now regarding hypersexual behaviour than before.

Aetiological models

Parts of this section report findings explored in Walton et al's (Reference Walton, Cantor and Bhullar2017) literature review.

Sexual compulsivity

DSM-5 defines compulsions as ‘repetitive behaviours or mental acts, the purpose of which is to prevent or reduce personal anxiety or distress, rather than to provide pleasure or gratification’ (American Psychiatric Association 2013). If the increased sexual urge interferes with other important non-sexual goals, then it is not considered as normal sexual behaviour (Howard Reference Howard2007). Sexual compulsivity may be stress related following trauma (Walton Reference Walton, Cantor and Bhullar2017). It could relate to a history of sexual abuse in childhood, which may lead to difficulty in regulating sexual desire, arousal and behaviour and successfully engaging in intimate relationships (Walton Reference Walton, Cantor and Bhullar2017). Hypersexual behaviour can be a way of coping with stress and escaping emotionally from painful memories such as rape, war-related trauma or death of a loved one (Walton Reference Walton, Cantor and Bhullar2017). Kafka (Reference Kafka2010) established that the neurotransmitters involved in compulsive sexual behaviours were monoamines, namely serotonin, dopamine and noradrenaline.

Sexual impulsivity

Sexual impulsivity has been described as the ‘inability to resist an impulse, drive or temptation to perform a sexual act that may be personally harmful’ (Walton Reference Walton, Cantor and Bhullar2017). This includes acting suddenly on a sexual urge with little thought before indulging in the sexual act. Such behaviour is attributed to ‘poor impulse control and faulty regulation of sexual motivations’ (Walton Reference Walton, Cantor and Bhullar2017).

Craving, a symptom of hypersexuality, induces activity mainly in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the ventral striatum, the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and the amygdala. Hence, these areas, mediated by dopamine, play a significant role in the dependence cycle, which begins by stimulation of dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental region projecting to the nucleus accumbens (the so-called reward centre). This cycle is associated with the repetition of a pulse-like increment in its glutaminergic projections to the prefrontal cortex, which alters brain function and creates neuronal pathways of addictive behaviour (Koob Reference Koob and Volkow2016).

Sexual excitation/inhibition

The dual control model of hypersexuality was originally developed to explore the tendency among men for sexual excitation and inhibition (Walton Reference Walton, Cantor and Bhullar2017). This led to the development and acceptance of the Sexual Inhibition/Sexual Excitation Scales (SIS/SES) (Walton Reference Walton, Cantor and Bhullar2017). Analyses of data from the SIS/SES identified a single sexual excitation factor: sexually arousing situations (for example, seeing an attractive person, watching an erotic video or being aroused by a particular smell); and two types of sexual inhibition: inhibition due to a threat of performance failure (for example, distractions) and inhibition due to the threat of performance consequences (for example, fear of unwanted pregnancy is said to predict a person's inclination towards sexual arousal) (Walton Reference Walton, Cantor and Bhullar2017). People with hypersexuality have been reported to be susceptible to ‘higher sexual excitation, lower sexual inhibition due to threat of performance failure and lower sexual inhibition due to the threat of performance consequences compared to the general population’ (Walton Reference Walton, Cantor and Bhullar2017).

Sex addiction

Early and chronic exposure to graphic cybersexual content can lead to hypersexual behaviour (Walton Reference Walton, Cantor and Bhullar2017). In an analysis of a vast amount of internet data, Ogas & Gaddam (Reference Ogas and Gaddam2011) estimated that 13% of online searches worldwide were related to erotic content. Analysing data from a survey conducted in 2015–2016 that included 1072 adolescents aged 11–16 across the UK, by Martellozo et al (Reference Martellozo, Monaghan and Davidson2020) found that 48% (n = 476) said they had seen online pornography and 52% (n = 525) said they had not. Of those who had seen online pornography, 65% were 15–16 years of age. Martellozo et al compare these findings with the study by the Child Exploitation and Online Protection Command (CEOP), which found that out of 2315 respondents aged 14 to 24, 34% said they had sent a nude or sexual image of themselves to someone they were sexually interested in. The motivations of young people taking and sending sexualised images include sexual gratification (by indulging in online sexual encounters) and sexual exhibitionism with online contacts (Martellozo et al Reference Martellozo, Monaghan and Davidson2020). For some, access to free, anonymous and unrestricted sex chat and pornography websites may lead to repetitive patterns of sexual behaviour that could be difficult to control (Walton Reference Walton, Cantor and Bhullar2017). They may become psychologically dependent on the euphoria related to ‘feel-good’ neurochemicals that are activated with sexual arousal (Walton Reference Walton, Cantor and Bhullar2017).

Neurobiology

Neurologically, hypersexual behaviour may be pathological rather than a liking for sex and the individual may feel unable to control their sexual behaviour (Walton Reference Walton, Cantor and Bhullar2017). Katehakis (Reference Katehakis2009) mentions that for some, the experience of emotional disengagement resulting from experiences such as childhood abuse, attachment-related trauma or neglect during childhood can have a significant impact on their neuropsychobiological development, particularly affecting the central nervous system (CNS), autonomic central nervous system (ANS) and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal system (the HPA axis). It is suggested that neurobiological deficits that develop in some of these individuals during early childhood can adversely affect their emotional and intellectual development, which could potentially cause the onset of sex addiction during adolescence and adulthood (Walton Reference Walton, Cantor and Bhullar2017).

In addition, dysfunction in the frontal cortical systems, which are responsible for decision-making and inhibitory control over sexual functioning, may lead to impaired judgement and impulsivity regarding sexual behaviour (Walton Reference Walton, Cantor and Bhullar2017). Idiopathic Kleine–Levin syndrome is characterised by recurrent episodes of hypersomnia and behavioural or cognitive disturbances, and some individuals also develop compulsive eating behaviour and hypersexuality (Arnulf Reference Arnulf, Rico and Mignot2012). Pathophysiology might involve hypoperfusion in diencephalic structures, especially the thalamus and hypothalamus (Arnulf Reference Arnulf, Rico and Mignot2012). Secondary Kleine–Levin syndrome is observed in association with genetic or developmental diseases, stroke or post-traumatic brain haematoma, multiple sclerosis, hydrocephalus, paraneoplastic syndromes, autoimmune encephalitis or severe infections (Arnulf Reference Arnulf, Rico and Mignot2012).

Kluver–Bucy syndrome is a rare neuropsychiatric disorder that can occur following traumatic brain injury. Its most common symptom is sexual hyperactivity, and lesion in the amygdala or amygdaloid pathways is considered to be the causative factor. The syndrome is also reported to be associated with destruction or dysfunction of bilateral mesial temporal lobe structures (Clay Reference Clay, Kuriakose and Lesche2019).

Assessment

In 2009, the Paraphilias Subwork-Group of the DSM-5 Workgroup on Sexual and Gender Identity Disorders proposed that ‘hypersexual disorder’ should be added as a distinct category in DSM-5, with the diagnostic criteria shown in Box 1. However, DSM-5 rejected the inclusion of hypersexual disorder as a separate category under the overall sexual and gender identity disorders. The reasons mentioned were (Reid Reference Reid and Kafka2014):

• lack of scientific research, inadequate neuropsychological testing and potential misuse of new sexual disorder diagnoses by the legal community, particularly in forensic settings where hypersexual disorder would potentially be used as a defence by hypersexual criminal defendants who are being prosecuted for crimes such as child abuse (Halpern Reference Halpern2011);

• hypersexual disorder has no place as a diagnosis but could possibly be an extension of other mental disorders (Halpern Reference Halpern2011).

BOX 1 Diagnostic criteria for hypersexual disorder proposed by the DSM-5 Paraphilias Sub-Workgroup

A. Over a period of at least six months recurrent and intense sexual fantasies, sexual urges or sexual behaviours in association with three or more of the following five criteria: -

1. Time consumed by sexual fantasies, urges or behaviours repetitively interferes with other important (non-sexual) goals, activities and obligations.

2. Repetitively engaging in sexual fantasies, urges or behaviours in response to dysphoric mood states for example anxiety, depression, boredom or irritability.

3. Repetitively engaging in sexual fantasies, urges or behaviours in response to stressful life events.

4. Repetitive but unsuccessful efforts to control or insignificantly reduce these sexual fantasies, urges or behaviours.

5. Repetitively engaging in sexual behaviours while disregarding the risks for physical or emotional harm to self or others.

B. There is clinically significant personal distress or impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning associated with the frequency and intensity of these sexual fantasies, urges or behaviours.

C. These sexual fantasies, urges or behaviours are not due to the direct physiological effect of an exogenous substance for example a drug of abuse or a medication.

-

Specify if:

-

Masturbation

-

Pornography

-

Sexual behaviour with consenting adults

-

Cybersex

-

Telephone sex

-

Strip clubs

-

Other.

-

-

D. The person is ≥18 years of age.

DSM-5 therefore lacks criteria for diagnosing hypersexuality or compulsive sexual behaviour.

In ICD-11 (which is scheduled to be implemented in January 2022) hypersexuality is termed ‘compulsive sexual behaviour disorder’ and defined as follows (see Kraus Reference Kraus, Krueger and Briken2018 for a discussion):

‘Compulsive sexual behaviour disorder is characterised by a persistent pattern of failure to control intense, repetitive sexual impulses or urges resulting in repetitive sexual behaviour. Symptoms may include repetitive sexual activities becoming a central focus of the person's life to the point of neglecting health and personal care or other interests, activities and responsibilities; numerous unsuccessful efforts to significantly reduce repetitive sexual behaviour; and continued repetitive sexual behaviour despite adverse consequences or deriving little or no satisfaction from it. The pattern of failure to control intense, sexual impulses or urges and resulting repetitive sexual behaviour is manifested over an extended period of time (e.g., 6 months or more), and causes marked distress or significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. Distress that is entirely related to moral judgments and disapproval about sexual impulses, urges, or behaviours is not sufficient to meet this requirement’ (World Health Organization 2021).

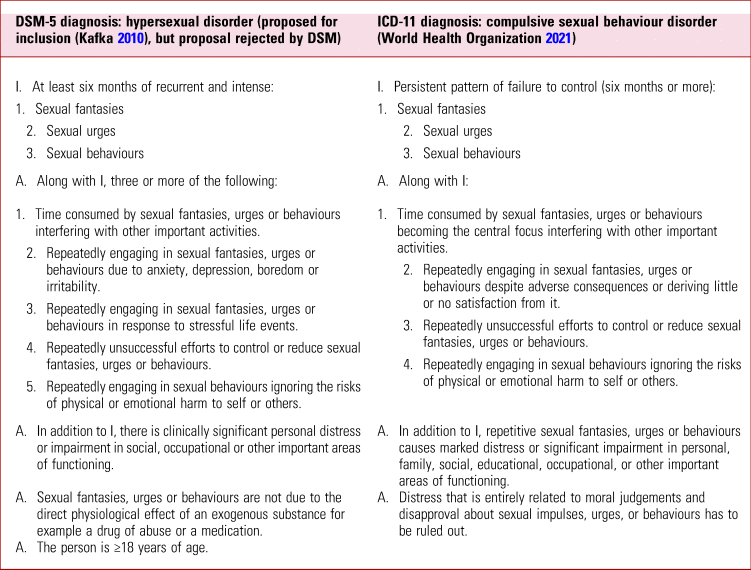

The diagnostic criteria proposed by the DSM-5 Paraphilias Sub-Workgroup and those currently set out in ICD-11 are compared in outline in Table 1.

TABLE 1 Comparison of the proposed diagnostic criteria for hypersexuality in DSM-5 and ICD-11a

a The proposed DSM-5 criteria are reprinted, with permission, from Kafka (Reference Kafka2010). The ICD-11 criteria are reprinted, with permission, from World Health Organization (2021) (will be published in 2022), © World Health Organization 2021.

People who present with hypersexuality may also have concurrent anxiety and depression due to the stress of the condition. A case report by Kalra (Reference Kalra2013) discusses a depressed man with underlying compulsive sexual behaviour in the form of compulsive frottage. Mina (Reference Mina2019) reports the case of a woman with depression who had a strong impulse to touch men inappropriately, even in the presence of family members.

It is worth noting that before treating hypersexuality the underlying pathology should be clarified. It is therefore crucial to exclude misuse of alcohol and substances (e.g. hallucinogenics, cocaine, amphetamines, propofol anaesthetics) and dopamine agonists treating Parkinsonism, restless leg syndrome and prolactinomas. Mania and hypergonadism should also be ruled out (Thibaut Reference Thibaut, Birchard and Benfield2018).

Hypersexuality in dementia

The diagnostic criteria for hypersexuality in people with dementia differ from those for hypersexual behaviour in younger adults. Diagnosis depends on the patient's ability to identify the person with whom sexual contact is being initiated and the level of sexual intimacy they would be comfortable with (Series Reference Series and Dégano2005). It also depends on the person's awareness of potential risk of exploitation (Series Reference Series and Dégano2005).

Screening instruments

According to a systematic review by Montgomery-Graham (Reference Montgomery-Graham2017), the Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory (HDSI) is the best available screening instrument for hypersexual disorder and its use is recommended in future clinical trials examining the disorder. Other tools identified include the Hypersexual Behavior Inventory, the Sexual Compulsivity Scale, the Sexual Addiction Screening Test, the Sexual Addiction Screening Test–Revised, and the Compulsive Sexual Behavior Inventory.

Differential diagnosis

Finlayson et al (Reference Finlayson and Martin2001) designed a decision tree to establish the diagnosis of hypersexual disorder. The first step is to rule out any medical causes. As previously mentioned, hypersexuality has been associated with neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson's disease, neurocognitive conditions such as dementia, traumatic brain injury and also the effects of certain drugs, such as dopamine used in dopamine replacement therapy (Callesen Reference Callesen, Scheel-Kruger and Kringelbach2013). Dopaminergic treatment may reduce sexual inhibition in the cerebral cortex and increase the motivational impulse for seeking sexual stimuli, resulting in hypersexual behaviour (Walton Reference Walton, Cantor and Bhullar2017).

The second step is to consider whether hypersexual disorder may be due to substance use (such as cocaine, methamphetamines, alcohol, marijuana and hallucinogens) or medications, as mentioned above.

The third step includes ruling out bipolar disorder or other functional psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia, delusional disorder (erotomania) or any other psychotic disorder.

The fourth step addresses hypersexuality associated with personality disorders. Personality disorders grouped in cluster B, which comprises borderline, antisocial, histrionic and narcissistic personality disorders, are most likely to be associated with hypersexual behaviour (Finlayson Reference Finlayson and Martin2001). If all these associated disorders are ruled out, the diagnosis of hypersexual disorder could be established.

Treatment

Psychological therapy

Although there is a lack of empirical studies on the efficacy of psychological therapies for hypersexual disorder, the psychotherapy modalities most widely used for the treatment of the disorder are cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT), psychodynamic psychotherapy, twelve-step or addiction treatment and couples therapy (Kaplan Reference Kaplan and Krueger2010).

A randomised controlled trial of CBT for hypersexual disorder suggested that CBT helps in reducing the sexual compulsivity and also reduces the depressive symptoms associated with the disorder (Hallberg Reference Hallberg, Kaldo and Arver2019). However, this study included only male participants. The authors recommended encouraging the participation of women in future trials and exploring the administration of online CBT (Hallberg Reference Hallberg, Kaldo and Arver2019). Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is a form of CBT indicated in hypersexual disorder triggered by problematic internet pornography viewing (Twohig Reference Twohig and Crosby2010). It emphasises acceptance of thoughts and urges, together with behavioural commitments to engage in therapy and its activities (Twohig Reference Twohig and Crosby2010). Experiencing sexual urges with acceptance, without acting on them, and while consistently performing self-monitoring can cumulatively lead to refraining from engaging in unwanted sexual behaviours, which in turn would lead to improved self-efficacy (Bandura Reference Bandura2012).

Psychodynamic psychotherapy explores the potential origins of hypersexuality. Fundamental themes include early childhood trauma, shame, avoidance, anger, and impaired self-esteem and self-efficacy (Bergner Reference Bergner2002). It is vital to explore how the person forms and maintains intimate relationships and the meaning of their sexual and romantic behaviour (Montaldi Reference Montaldi2002). Psychodynamic therapy would explore the intrapsychic and interpersonal dynamics that underlie the individual's sexual behaviours and fantasies in relation to their history and current relationships, including that with the therapist (Efrati Reference Efrati, Gerber and Tolmacz2019). In addition, it identifies and works through emerging ‘therapy-interfering’ behaviours that would negatively affect treatment of hypersexuality (Montaldi Reference Montaldi2002). Therapy-interfering behaviours could appear to be intentional or unintentional. They include not adhering to the therapy, being flirtatious with the therapist, exhibiting passive or aggressive behaviours and displaying anxious and avoidant tendencies towards the therapist (Chapman Reference Chapman, Rosenthal, Chapman and Rosenthal2016).

The twelve-step therapy model helps individuals to hold a sense of responsibility about their behaviour in a safe environment. Treatment goals are focused on helping the individual to stop or control their problematic behaviour, as well as to learn new coping strategies. In treating compulsive sexual behaviour these programmes are usually an adjunct to other modes of therapy (Carnes Reference Carnes2000). Examples of twelve-step self-help programmes include Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous, Sex Addicts Anonymous, Sexaholics Anonymous and Sexual Compulsives Anonymous (Carnes Reference Carnes2000).

Couples therapy may be used to address the suggestion that, for some individuals, hypersexuality could be a reflection of a ‘relationship disorder’ (Cooper Reference Cooper, Marcus, Levine, Risen and Althof2003). Dealing with the expectations of each partner in a couple, identifying emotional vulnerabilities, building up trust, honesty and learning skills of intimacy are integral concepts that Brown (Reference Brown1999) highlights for couples therapy. Lasser (Reference Lasser, Carnes and Adams2002) describes adaptations to couples therapy from the twelve-step model, underlining that the focus of therapy needs to be redirected to establishing the longer-term pleasure goal of nurturing intimacy rather than depending on the immediate short-term pleasure associated with hypersexuality.

Relate (the largest provider of relationship support in the UK) and Relationships Scotland have recommended that clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) should improve access to sex therapy services as a part of the National Health Service (NHS) in England (Marjoribanks Reference Marjoribanks and Bradley2017). Currently this service is not available in all areas of the UK so, depending on their location, some couples may have to fund their treatment themselves. To address the lack of services within the NHS that specifically treat sexual disorders such as hypersexual disorder, Marjoribanks & Bradley (Reference Marjoribanks and Bradley2017) made the following recommendations:

• the sexual relationship support service should be expanded so that it is easily accessible to NHS service users

• policy makers should raise awareness about the sexual health problems and dysfunction and include them in their national health outcome frameworks

• the commissioning of sex therapy services should include evaluation to establish effective evidence-based practice and provide cost–benefit analyses

• front-line health professionals should receive special training about sexual relationships and their impact on health and well-being.

Pharmacological therapy

Most of the medications used in hypersexuality are prescribed off-label (off-licence) and the evidence base on their use is generally weak.

In a 12-week double-blind trial of citalopram (20–60 mg) versus placebo, the outcomes showed significant reduction in libido, masturbation and pornography use, yet there was no reduction in having many sexual partners (Wainberg Reference Wainberg, Muench and Morgenstern2006). Fluoxetine may also help to improve some features of hypersexuality in men, although there have been no randomised controlled trials of the treatment (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2015). Naltrexone has been used as an off-label medication for hypersexuality as it is an inhibitor of endogenous and exogenous opiates and to block dopaminergic release in the nucleus accumbens. It acts on the reward system by blocking the positive reinforcement of addictive behaviour by a mechanism similar to that engaged in the treatment of alcohol and opioid addiction (Verholleman Reference Verholleman, Victorri-Vigneau and Laforgue2020). A number of case reports support the use of variety of other agents, such as naltrexone by itself or in combination with citalopram, clomipramine and valproic acid (Raymond Reference Raymond, Grant and Kim2002).

Other medications used to treat hypersexuality include mood stabilisers such as lithium and valproate, and antipsychotics used to treat other psychiatric illnesses (e.g. bipolar disorder or psychosis) (Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg, Carnes and O'Connor2014). However, it is important to stress that some antipsychotic medications could actually lead to hypersexuality. Aripiprazole, and also clozapine and even risperidone, have been reported to cause hypersexuality themselves (Koener Reference Koener, Hermans and Maloteaux2007). The mechanism by which aripiprazole could possibly do this is that it is a partial D2 agonist that works on hypersensitive dopamine receptors; this might lead to a boosted dopamine action in the mesolimbic pathway, favouring the agonist effect of aripiprazole and hence leading to this behaviour (Koener Reference Koener, Hermans and Maloteaux2007).

In a double-blind controlled study comparing it with chlorpromazine and placebo, benperidol was found to have some ‘reducing effect’ on libido, in that it participants reported a lower frequency of sexual thoughts (Tennent Reference Tennent, Bancroft and Cass1974). Most studies of medication for hypersexuality have included only men, leaving very limited data on effective medications to treat the disorder in women.

Treatment in dementia

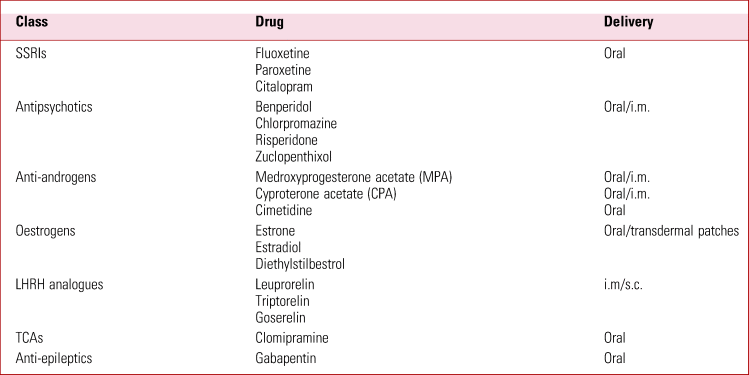

Table 2 lists some of the drugs that have been used off-licence to treat hypersexuality in people with dementia.

TABLE 2 Some of the drugs that have been used as off-licence treatment of hypersexuality in dementia

i.m., intramuscular; LHRH, luteinising hormone-releasing hormone; s.c., subcutaneous.

Sources: Series (Reference Series and Dégano2005), DeGiorgi & Series (Reference DeGiorgi and Series2016).

Research implications

Further research is required to determine the pharmacological treatment of choice for hypersexual disorder. Future clinical trials could focus on treatments to regulate oxytocin levels in addictive behavioural disorders (Lee Reference Lee, Rohn, Tanda and Leggio2016).

Conclusions

Hypersexual disorder is a very controversial subject. There is sufficient literature available on its clinical presentation, but limited data regarding epidemiology and management. This might be due to barriers to presentation, research and treatment mentioned above in relation to women, but that relevant to men also, which can make the diagnosis very subjective. There have been efforts made in the past to clearly define hypersexual disorder without any overlap with other mental health disorders. DSM-5 rejected the addition of ‘hypersexual disorder’ as a diagnosis, but ICD-11 has approved its addition, as ‘compulsive sexual behaviour disorder’. ICD-11 will be implemented from January 2022. There is insufficient evidence regarding the treatment options available, largely because of the difficulty in recruiting participants to studies. Most small clinical trials done in the past have only included men, thus providing very limited treatment options for women. The key is to acknowledge that hypersexual disorder exists and that more awareness is required. This will facilitate robust clinical trials, which will eventually lead to better clinical outcomes.

Author contributions

H.E. contributed to the aetiology, assessment, treatment, reading objectives and MCQs. Q.J. worked on epidemiology, aetiological model assessment and differential diagnosis. Both authors contributed to the manuscript amendments and submissions.

Funding

None.

Declaration of interest

None.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2021.68.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 Concerning the pathophysiology of hypersexuality, which one of the following is incorrect:

a organic brain lesions could present with hypersexuality

b Kleine–Levin syndrome presents with hypersomnia along with hypersexuality

c oxytocin signaling pathway is involved/implicated in the pathogenesis of hypersexuality

d monoamines are not associated with hypersexual behaviour

e emotional detachment could be one of the contributing factors to sexual addiction.

2 Concerning the epidemiology and diagnosis of hypersexuality:

a women are more likely to seek help than men

b there is more awareness about hypersexuality than in the past

c ICD-10 includes hypersexuality as a separate diagnostic entity

d the prevalence of hypersexuality in adults is estimated to be 6%

e nymphomania is known in males.

3 Hypersexuality:

a may be associated with a sudden surge in glutamate in the prefrontal cortex

b is neither an impulsive nor a compulsive behaviour

c is not associated with early exposure to cyberporn

d does not affect the individual's life or functioning

e is rarely associated with any risk behaviour.

4 ICD-11:

a includes hypersexuality as a sole diagnosis (compulsive sexual behaviour disorder)

b includes hypersexuality only as a part of other diagnoses

c declined to include hypersexuality as either a symptom or a disorder

d does not include indulging in repetitive sexual activities as a pivotal criterion for diagnosing hypersexuality

e gives 18 years as the minimum age for diagnosing hypersexuality.

5 Psychological therapies that work in treatment of hypersexuality are:

a psychodynamic therapy

b cognitive–behavioural therapy

c twelve-steps (addiction) treatment

d acceptance and commitment therapy

e all of the above.

MCQ answers

1 d 2 b 3 a 4 a 5 e

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.