LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article you will be able to:

• understand the similarities and differences between the DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 PTSD diagnoses

• understand why PTSD is a disorder of memory and how to differentiate PTSD memories and ordinary episodic memories of psychologically threatening experiences

• understand how to assess PTSDs for medico-legal purposes.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a complex mental health problem that can be challenging to identify, assess, understand, diagnose and treat. DSM-5-TR (American Psychiatric Association 2022) and ICD-11 (World Health Organization 2022) have adopted different approaches to PTSD diagnosis, with ICD-11 distinguishing PTSD and complex PTSD (CPTSD) sibling diagnoses. This article provides an overview and critique of key topics, literature and principles to inform comprehensive and meticulous assessment of DSM-5-TR PTSD and ICD-11 PTSD and Complex PTSD, which are referred to collectively as PTSDs for the remainder of the article. Although expert witnesses are the target audience, the article will have relevance for identifying, assessing, understanding and diagnosing PTSDs in all clinical contexts.

Trauma and PTSDs

Exposure to trauma and adversity is near ubiquitous (Kessler 2010; Benjet Reference Benjet, Bromet and Karam2016). Trauma exposure is a transdiagnostic risk factor, increasing the likelihood of developing a range of psychological and physical problems and disorders. How best to define and understand what is and is not ‘traumatic’ and whether and how to include trauma exposure as a diagnostic criterion for PTSDs have been long debated, with no definition addressing all the problems and complexities that have been identified (Brewin Reference Brewin, Lanius and Novac2009; Larsen 2016; Siddaway 2020).

A growing body of evidence demonstrates that PTSDs are not more likely to follow traumatic events defined by DSM-5-TR Criterion A than non-Criterion A stressors (Larsen 2016; Franklin 2019; Hyland 2021), and psychologically threatening experiences such as bullying, stalking, emotional abuse, rejection and neglect – which would not be captured by DSM-5-TR Criterion A – predict ICD-11 PTSD and CPTSD independent of Criterion A events (Hyland 2021) (the DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 criteria are outlined in the Diagnosis section below). There is also evidence that PTSDs can develop in relation to events that cannot be recalled (e.g. owing to head injury) and events that did not physically occur (e.g. hallucinations due to psychosis or intensive care experiences) (Brewin Reference Brewin, Rumball and Happé2019b). It is difficult to clearly distinguish between life events, stressors, adversities and traumas (Siddaway 2020), which brings into question the proposal to refer to traumatic events as ‘potentially traumatic events'. Furthermore, meta-analyses of risk factors for PTSDs evidence that an individual's interpretation of what happened to them, how they coped and how their social environment responded are more important predictors than the ‘objective’ severity of the trauma(s) experienced (Brewin Reference Brewin, Andrews and Valentine2000; Trickey 2012).

Overall, the literature illustrates that trauma exposure is necessary but not sufficient for developing PTSDs, there are individual differences in vulnerability to the effects of any given traumatic event and the development of PTSDs involves a complex interaction between pre-, peri- and post-trauma biopsychosocial risk/vulnerability and resiliency/protective variables. Taking all the complexities and issues that have been raised in the literature into account, trauma exposure is probably best understood, and defined in future iterations of the DSM and ICD, as exposure to one or more psychologically threatening or horrific experiences that are overwhelming.

The complexity and controversy around the definition of PTSDs and their aetiology have provided fertile conditions for confusion and misunderstanding. For example, ‘complex trauma’, which denotes an experience, is regularly used to describe the impact of experiences on mental health (e.g. CPTSD), and phrases such as ‘trauma symptoms’ are used to refer to PTSD symptoms and/or other mental health difficulties in someone who has reported experiencing trauma. Evidence of a highly complex relationship between psychologically threatening experiences and PTSDs, coupled with the fact that traumatic events vary in terms of numerous characteristics (e.g. type, form of exposure, severity, duration, frequency, threat to life, bereavement, interpersonal nature, physical injury, sexual violation) – each of which plays a role in explaining individual differences in the development of PTSDs – challenges the widespread notion that it is accurate to reduce traumatic experiences to ‘complex/Type II’ versus ‘simple/Type I’ categories. Additionally, recent years have seen a trend advocating stopping asking ‘What's wrong with you?’ and instead asking ‘What happened to you?’ Although well-intended, this mantra may inadvertently suggest a simplistic, deterministic (1:1) relationship between experiences and their impact (e.g. PTSDs) – and does not acknowledge people's goals and potential for change. Expert witnesses need to have a precise understanding of PTSDs because the courts welcome precise clinical impressions and recommendations: imprecise thinking and language do not help the court, the person being assessed or the expert's reputation.

Onset and course of PTSDs

Many people experience at least some PTSD symptoms after extremely threatening events, which usually subside of their own accord after days or weeks (Ehlers Reference Ehlers and Clark2000). Most people rebound to pre-trauma levels of psychological functioning. However, a significant number of people develop PTSDs (Koenen 2017). Prototypical trajectories of PTSDs have been identified across independent studies in relatively consistent proportions. These trajectories/groups include ‘unaffected’Footnote a (relatively stable psychological health following trauma(s); ~66% of people), ‘recovery’ (PTSDs reduce over time; ~21% of people), ‘chronic’ (PTSDs do not reduce with time; ~11% of people) and ‘delayed onset’ (PTSDs develop after a delay; ~9% of people) trajectories/groups (Galatzer-Levy 2018).

As regards duration/prognosis, the mean duration of PTSDs averages approximately 6 years across all traumas and varies greatly between and within trauma types (e.g. 13.5 years (s.e. = 2 years) for traumas involving war combat; 4 years (s.e. = 1 year) for road traffic accidents; Kessler 2017). If maintaining factors (e.g. avoidance) persist, PTSDs can endure for a lifetime,Footnote b often involving waxing and waning patterns of symptoms and functional impairment.

Diagnosis

Accurate diagnosis of PTSDs is dependent on being fluent with the diagnostic criteria for PTSDs (Table 1) and other disorders.Footnote c As stated, ICD-11 includes the sibling diagnoses of PTSD and CPTSD, whereas DSM-5-TR does not make this distinction. A CPTSD diagnosis involves meeting all ICD-11 symptoms of PTSD (re-experiencing in the present, avoidance, and sense of threat, with associated functional impairment) and evidencing symptoms referred to as ‘disturbances of self-organisation’ (DSO) (persistent and pervasive impairments in emotion regulation, self-concept and interpersonal functioning, with associated functional impairment). Although substantial evidence supports the distinction between ICD-11 PTSD and ICD-11 CPTSD (Brewin Reference Brewin, Cloitre and Hyland2017b), these categories are probably best understood as a convenient means of describing continuous variables (Wolf 2015; Kotov 2017; Achterhof Reference Achterhof, Huntjens and Meewisse2019). ICD-11 CPTSD appears to generally be a more common presentation than ICD-11 PTSD in clinical settings, while the reverse is generally apparent in community and general population samples (Brewin Reference Brewin, Cloitre and Hyland2017b; Hyland 2024).

Table 1. ICD-11 and DSM-5-TR diagnostic criteria for posttraumatic stress disorders

ICD-11, International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision; DSM-5-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision. Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (Copyright © 2022). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved.

The DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 conceptualisations of PTSD are, predictably, similar, with some notable differences. The ICD-11 ‘core’ symptoms of PTSD are similar to DSM-5-TR criteria B, C and E, and ICD-11 CPTSD DSO symptoms are similar to DSM-5-TR criteria D and E. The ICD-11 definition of a traumatic event is broader and more inclusive than the DSM-5-TR definition and the same definition of trauma exposure is specified for PTSD and CPTSD: differential diagnosis between PTSD and CPTSD is determined by symptoms (i.e. impact), not experiences (Brewin Reference Brewin, Cloitre and Hyland2017b). The DSM-5-TR diagnosis aims to describe the heterogeneity of PTSD in detail, allowing for a wider range of symptom profiles to be classified as PTSD, but increasing the overlap with other mental health difficulties. The ICD-11 diagnosis takes a more restricted approach, aiming to make diagnosis as simple as possible but potentially missing individuals who have less-common patterns of symptoms and thus excluding access to healthcare services for some individuals.

Many of the DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 diagnostic criteria for PTSDs are not trauma-related and almost all PTSD symptoms are transdiagnostic (i.e. common to several mental health problems/diagnoses). Involuntary thoughts, images and memories are experienced by everyone: positive, negative and neutral material spontaneously pops into everyone's minds without disrupting life. Recurrent, intrusive (i.e. distressing) thoughts, images and memories (Brewin Reference Brewin, Gregory and Lipton2010, Reference Brewin2014), and repetitive nightmares (Sheaves 2023), are transdiagnostic. Although intrusive memories often induce bodily reactions and feelings associated with the original experience(s), individuals remain aware of the here and now and that they are recalling a memory.

The only symptom unique to PTSDs is reliving/re-experiencing, which involves vivid, decontextualised, threatening multisensory material repeatedly entering awareness involuntarily, creating a sense that past threatening events are happening again in the present moment (Brewin Reference Brewin, Gregory and Lipton2010, Reference Brewin2014, Reference Brewin2015). Reliving involves a small number of primarily visual, personally significant parts of experiences and a range of emotions entering awareness unbidden (Ehlers Reference Ehlers and Steil1995; Hackmann 2004; Holmes 2005). The ‘warning signal’ hypothesis suggests that reliving involves involuntary recollection of multisensory/perceptual material experienced shortly before the meaning of experiences became most threatening (Ehlers Reference Ehlers, Hackmann and Steil2002).

‘Flashbacks’ have been defined differently over time. DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 assign flashbacks an overarching meaning that is synonymous with reliving/re-experiencing when awake. Flashbacks involve an intense sense of current threat and range from fleeting (a transient sense of traumatic experience(s) re-occurring in the present) to extreme (total disconnection from the current autobiographical self and one's present surroundings for minutes or longer). Thus, at present, the flashback concept/continuum encapsulates intrusive trauma memories.

It is for expert witnesses rather than the courts to consider these technical issues and the most accurate and informative means of conceptualising an individual's mental health for the court (e.g. the benefits of DSM-5-TR versus ICD-11 conceptualisations of PTSD; the validity and reliability of categorical psychiatric diagnoses versus empirically derived dimensions (Kotov 2017) or psychological formulations). Clinical and counselling psychologists may provide a psychological formulation alongside a diagnosis to describe and explain presenting difficulties.

Psychological models of PTSD

There is an adjustment and meaning-making process after trauma: people need to make sense of what they have experienced. Various internal and external factors can interrupt this natural process. Cognitive models of PTSDs – which are supported by a large evidence base – propose that PTSDs occur when individuals encode, appraise and cope with traumatic experiences and/or their sequelae in a way that produces an intense sense of current, ongoing threat (Brewin Reference Brewin, Dalgleish and Joseph1996; Ehlers Reference Ehlers and Clark2000; Hyland 2023).

Memory processes

Cognitive models of PTSDs hypothesise that re-experiencing occurs because of how memories of traumatic experiences are encoded, organised and retrieved (Brewin Reference Brewin, Dalgleish and Joseph1996, Reference Brewin2014; Ehlers Reference Ehlers and Clark2000; Hyland 2023). Table 2 outlines key theoretical and phenomenological differences between the memories that characterise PTSDs and ordinary episodic memories of extremely psychologically threatening experiences. According to the dual representation theory of PTSD (Brewin Reference Brewin, Dalgleish and Joseph1996, Reference Brewin, Gregory and Lipton2010), the storage of episodic memories relating to any experience (positive or negative) involves two separate memory and representation systems: (a) sensation-based representations (S-reps) encode multisensory/perceptual (primarily image-based) information, supported primarily by subcortical structures and areas of the brain directly involved in perception; and (b) contextually bound representations (C-reps) encode cognitive and spatial information, including the current autobiographical self, and involve higher-order cognitive activity. Ordinary, functional encoding (of positive memories, negative memories and processed PTSD memories) in episodic memory involves the creation of C-reps and S-reps, with connections between the two. In contrast, re-experiencing results from the creation of an S-rep (perceptual memory) without the usual association to a corresponding C-rep.

TABLE 2 Theoretical and phenomenological differences between post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) memories and ordinary episodic memories of extremely threatening experiences

S-rep, sensation-based representations; C-rep, contextually bound representations.

The dual representation theory (Brewin Reference Brewin, Dalgleish and Joseph1996, Reference Brewin, Gregory and Lipton2010, Reference Brewin2014) hypothesises that reliving arises if, during extreme stress and horror, an individual's brain prioritised encoding survival-related perceptual information and action over higher-order cognitive activity. Increased encoding into S-reps and reduced encoding into C-reps and the connections between S-reps and C-reps result in multisensory information not being encoded with enough contextual information, with the result that it can only be recalled involuntarily when automatically triggered by trauma reminders. This leads to the brain responding as though past experiences are happening again in the present, producing intense reliving, with associated emotional and physiological reactions. These issues mean that individuals can retrieve C-reps of experiences when they want to deliberately think or communicate about them, but these are fragmented and disorganised.

Reliving can be thought of as the brain trying to make sense of experiences: re-presenting information for more detailed processing when the danger has passed. ‘Processing’ traumatic experiences (with or without professional support) involves holding intrusive trauma memories in focal attention, strengthening C-reps and the connections between C-reps and S-reps such that multisensory information is given a temporal and spatial context and fits with the current autobiographical self and core beliefs.

Problematic meanings

The second mechanism hypothesised by cognitive models to be central to explaining the development and maintenance of PTSDs is the appraisals people have regarding traumatic experiences and their sequelae and what these mean for the self (Ehlers Reference Ehlers and Clark2000; Hyland 2023). PTSDs are characterised by threatening, excessively negative or distorted – and therefore unhelpful – appraisals/beliefs about traumatic experiences and/or their consequences. The memory and identity theory proposes that ICD-11 PTSD and CPTSD are distinguished by the types of negative identities/beliefs present, with ICD-11 PTSD involving identities centred on experiencing the self as powerless and unsafe, whereas ICD-11 CPTSD additionally involves identities related to experiencing the self as worthless/inferior, betrayed/abandoned, alienated, fragmented and/or non-existent (Hyland 2023).

Maladaptive coping

Cognitive models of PTSDs hypothesise that the manner in which individuals cope is another psychological mechanism that is central to explaining the development and maintenance of PTSDs (Ehlers Reference Ehlers and Clark2000; Hyland 2023). Individuals use a range of cognitive and behavioural avoidance strategies to cope with a sense of current threat and PTSD symptoms because these experiences are too distressing and/or cannot be understood within the person's current core beliefs/identity. Unfortunately, these management strategies inadvertently maintain PTSDs by directly producing PTSD symptoms, preventing change in negative appraisals of trauma and/or its sequelae, and preventing change in the nature of the trauma memory (Ehlers Reference Ehlers and Clark2000).

Individual differences in vulnerability

Cognitive models of PTSDs recognise individual differences in vulnerability to developing PTSDs. Ehlers and Clark's (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) model provides the most detailed discussion of the range of ways in which background factors are likely to influence cognitive processing during traumatic events, the nature of trauma memories, appraisals of trauma/its sequelae and the strategies used to control perceived threat/PTSD symptoms.

Neuropsychological changes

A substantial evidence base demonstrates that, compared with individuals exposed to trauma but not experiencing PTSDs and individuals not exposed to trauma, individuals experiencing PTSDs evidence deficits in various neuropsychological abilities – which are similar irrespective of the type of the trauma experienced (Scott 2015; Malarbi 2017). Cognitive abilities are not fixed at birth: developing cognitive abilities to one's potential requires stimulation via exposure to learning opportunities. In adults (who have completed school and whose brains were fully developed before PTSD onset), resolution of PTSD is generally accompanied by neuropsychological improvements towards pre-trauma cognitive functioning. Anecdotally, alleviating an individual's PTSD tends to have a small (less than 1 s.d.) positive impact on cognitive abilities and a large or very large impact on distress and everyday functioning, including education and employment prospects and interpersonal relationships. Experiencing mental health problems such as PTSDs as a child or adolescent (when the brain is still developing) can hinder cognitive abilities developing to their potential, and the impact on cognitive development is often greater the earlier the onset of mental health problems.

Functional impairment (disability)

PTSDs confer increased mortality risk (Nilaweera 2023) and predict worse educational (Bachrach Reference Bachrach and Read2012; Boyraz et al 2016; Vilaplana-Pérez 2020) and occupational (Ehlers Reference Ehlers and Clark2000; Wald 2009) performance and outcomes. It is impossible to predict with sensitivity and specificity what an individual's educational and occupational performance and outcomes would have been were it not for certain experiences or PTSDs, because educational and career performance and outcomes are the result of a complex interplay between a range of factors over time. Moreover, the relationship between PTSDs and educational and occupational performance and outcomes is complex and idiosyncratic. Some PTSD symptoms (e.g. poor sleep, reduced motivation) and behaviours used to manage them (e.g. substance or alcohol use, social withdrawal) may exert a deleterious effect on educational and occupational performance and outcomes, social relationships, criminal behaviour and other outcomes. Equally, school attendance, work, exercise or reading may have been used to manage re-experiencing symptoms. Thus, although it may not be the neat picture legal professionals seek, expert witnesses can only opine what seems most likely, prognostic predictions need to be carefully phrased and caveated, and it is best to specify that different things are true and likely when this is the case.

Assessment

The information above provides a foundation for the assessment of PTSDs for medico-legal and other clinical purposes. It goes without saying that such assessments need to be trauma-informed, involving gentle questioning, collaboration and a calm, non-judgemental interviewer manner, and that careful, systematic assessment and precise thinking are critical.

Depending on the context, an expert witness's assessment of PTSDs may entail assessing some or all of the following: (a) risk/vulnerability factors before one or more index events, including mental health difficulties, mental health treatment, previous trauma exposure and everyday functioning, as well as protective factors that may have mitigated the deleterious effects of trauma/adversity; (b) the onset, nature, frequency, duration, severity and course of index event-related mental health problems, particularly focusing on psychiatric diagnostic criteria; (c) the relationship between index event-related physical health problems and an individual's mental health; (d) whether and how any index event-related mental health problems have impaired educational and occupational performance and outcomes, activities of daily living, interpersonal relationships, hobbies and interests, and other important life areas (e.g. parenting); (e) significant stressors and treatments since an index event, including whether an individual's life circumstances mean they do not perceive that they are post-trauma (i.e. the trauma is not in the past); (f) developmental, systemic, neurodevelopmental and cultural factors that may be important to understanding an individual's clinical presentation (e.g. PTSDs manifest more behaviourally in younger children; caregiver reports are more necessary with younger children; caregiver mental health is an important determinant of child mental health; older persons may downplay or not volunteer symptoms; cultural differences in understanding trauma and PTSDs might mean that symptoms manifest or are described as primarily somatic); and (g) an individual's perceptions of and any contraindications to interventions. Some more specific principles for assessing PTSDs are outlined in the subsections below and some example assessment questions are provided in Table 3. The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM–5 (CAPS-5; Weathers 2018) also provides example assessment questions.

TABLE 3 Example questions for assessing post-traumatic stress disorders

The clinical interview in more detail

After outlining the individual's ethical rights and setting up the assessment, expert witnesses are advised to begin assessments with open questions and free recall, as these are the most effective means of eliciting large amounts of uncontaminated information. Briefly asking individuals about current home circumstances and education/employment, for example, helps establish rapport. Individuals can then be asked to tell the story of the index event(s) (describe what happened); if distress or potential PTSD symptoms (e.g. avoidance) are observed, reflective questions might be asked about what it is like to think and talk about these experiences. These initial sources of information help establish rapport and swiftly elicit a wealth of clinical information pertinent to the expert's aims, informing preliminary hypotheses about possible and likely diagnoses and psychological formulations, and identifying potential inconsistencies and information that will need assessing in more detail.

Continuing to use primarily open (non-leading) questions, the expert can then move to more specific assessment of an individual's mental health over time using cued invitations (e.g. ‘Tell me more about X’), direct questions (concerning who, what, when, where, how, why), and a mixture of open and closed questions, aiming to elicit further details and clarify unclear and contradictory information. The diagnostic criteria for any mental health problems being reported (e.g. PTSDs) need to be comprehensively assessed.

Expert witnesses may assess pre-, peri- and post-index-event variables, and how cognitions, behaviour and functioning have changed from before to after experiences. A theory-informed assessment of PTSDs – which considers memory characteristics, problematic meanings and maladaptive coping – is recommended and further informs: (a) why a particular individual developed PTSDs when they did; (b) understanding maintaining factors and treatment targets; (c) differential diagnosis; and (d) attributing mental health problems and functional impairment/disability to specific events when an individual has experienced multiple traumas. The nature of reliving (i.e. what intrusive memories, flashbacks and nightmares are about) and the appraisals people have about traumatic experiences and/or their consequences help in understanding the differential and cumulative impact of different experiences of trauma and adversity.

As the clinical interview continues, the focus shifts from sensitivity (identifying relevant mental health difficulties) to specificity (accurate diagnosis and psychological formulation). If two or more diagnoses might plausibly describe an individual's index event-related mental health problems, further information-gathering may be needed. The assessment continues until uncertainty about the most accurate diagnostic impression and psychological formulation are minimised.

Administering psychometric instruments

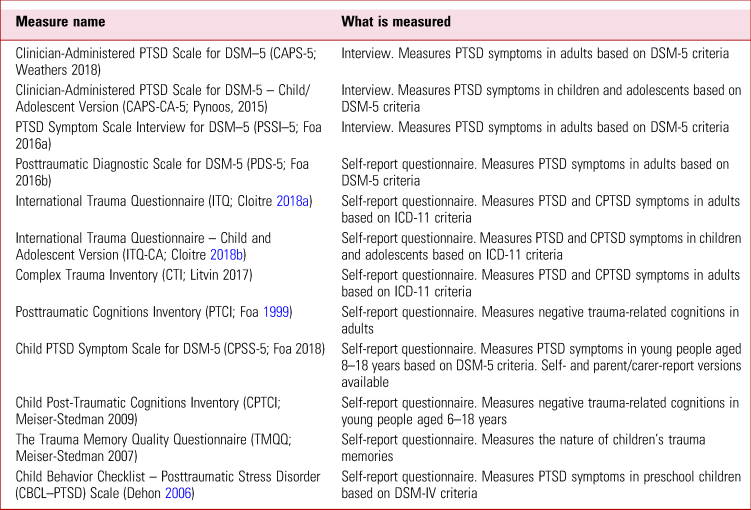

Expert witnesses may collect psychometric information about an individual's PTSDs and other mental health problems to corroborate and extend information gathered during clinical interview. Measures usefully quantify the presence and severity of symptoms. Some example PTSD measures are provided in Table 4. There are advantages and disadvantages to different approaches: semi-structured interviews ensure systematic, comprehensive assessment of diagnostic criteria and provide the highest inter-rater reliability, but are more time-consuming to administer, whereas questionnaires collect large amounts of clinical information swiftly and easily but may be more susceptible to bias than interviews. Some professionals fear that collecting self-report information ahead of a clinical interview may influence clinical interview responses; I have not observed this myself and I am not aware of any evidence for or against this hypothesis.

TABLE 4 Some example measures of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex PTSD (CPTSD)

When PTSDs are being considered as a legal defence

PTSDs may be considered as a legal defence to argue for temporary diminished responsibility, loss of capacity, insanity or duress, or as a mitigating factor in sentencing. In addition to the considerations discussed above, the expert witness's role in such circumstances is to carefully assess how PTSD symptoms relate to specific (criminal) behaviours. For example, a flashback could plausibly cause a temporary, abrupt behaviour change beyond the person's volition (‘automatism’; Kopelman 2022); an individual's perceptions, decision-making and capacity for self-control may have been influenced by trauma-related beliefs/expectations (e.g. heightened perceptions of threat); irritability and aggression may have made an individual easily provoked; negligent behaviour may have occurred due to chronic insomnia. In cases of memory loss specifically for an offence, it is important to determine whether memory loss was partial or complete and to ask about the onset of amnesia and the return of normal, continuing memories and any ‘islets’ of memory in between (Commane Reference Commane and Kopelman2022).

Further comments about differential diagnosis

It is beyond the scope of this article to review the numerous possible and likely alternative diagnoses to PTSDs but some general comments can be made. First, since PTSDs are a disorder of memory, an intimate understanding of trauma memory characteristics (Table 2) is critical to differential diagnosis. Second, meticulous interviewing and thinking are required to form and clearly describe accurate clinical impressions. Third, accurate differential diagnosis is obviously dependent on fluent knowledge of the diagnostic criteria for a range of diagnoses. A common error involves mistaking the reliving symptoms that specifically characterise PTSDs with (a) ‘thinking about’ trauma only when reminded; (b) non-intrusive memories of traumatic experiences; (c) intrusive thoughts, images and memories (which are transdiagnostic); (d) blaming oneself or others; or (e) trauma-related preoccupation, worry or rumination (which involves repetitive ‘coulda/woulda/shoulda’ thoughts and focusing on how bad one's life is or could have been because of one or more experiences). Another common mistake involves not delineating different mental health problems/disorders and whether and how they interact. The most obvious way to accurately differentially diagnose involves carefully assessing and describing the nature of trauma-related mental health responses and how different diagnostic criteria are or are not met.

Factors that may affect reliability

Broadly speaking, the evidence base indicates that memory is essentially reliable but malleable and subject to contamination under certain circumstances; that memory quantity and the richness of episodic detail decline as the retention period increases, although the details people do recall are pretty accurate across time; that it tends to be more difficult to recall thoughts and feelings than it is to recall events; that the reliability and accuracy of recollections cannot be easily verified by other people (including professionals) except by reference to other sources of information; and that susceptibility to false memories of childhood events appears more limited than has sometimes been suggested (Brewin 2011a, Reference Brewin and Belli2011b, Reference Brewin2014, Reference Brewin and Andrews2017a, 2019a, Reference Brewin, Andrews and Mickes2020; Wixted 2018; Commane Reference Commane and Kopelman2022; Baddeley Reference Baddeley, Brewin and Davies2023). Civil claims and repeated interviews about past distressing events invite individuals to reflect on past experiences, sometimes leading to re-interpretation of past events, potentially attaching to events a significance that they did not originally have. The phenomenological characteristics of PTSDs (Table 2) may affect perceptions of an individual's reliability.

Expert witnesses must critically consider the extent, nature, consistency and quality of the available evidence when diagnosing, formulating and caveating their professional opinions. When considering records and collateral information, it is important to remember that informant discrepancies are common (De Los Reyes Reference De Los Reyes, Augenstein and Wang2015) and perceptions of other people's difficulties and abilities vary greatly in accuracy, detail and degree of bias, depending on a range of factors. Corroborating information across varied sources, time and contexts helps overcome biases and weaknesses in any one information source. More generalised and caveated professional opinions about mental health difficulties and psychiatric diagnosis are appropriate for events that are more distant in time, when there is less available information and when the information available is of poorer quality or inconsistent. Highlighting inconsistencies, gaps and contradictions in the available evidence and discussing possible and likely reasons for these valuably informs the court, but expert witnesses must always stick to their role: it is for the court to make determinations on fact.

Treatment

A large body of research has tested the efficacy and effectiveness of pharmacological, psychological and other treatments for PTSDs. Meta-analyses of the adult literature indicate that some medications have a small positive effect on symptom severity and there is little evidence for the superiority of one medication over another (de Moraes Costa Reference de Moraes Costa, Zanatta and Ziegelmann2020; Hoskins 2021). Very few trials have tested psychopharmacological interventions for paediatric PTSDs (Morina 2016).

Trauma-focused psychological therapy

Trauma-focused psychological therapy (TFPT) is recommended as the first-line treatment for PTSDs in all populations in guidelines across the world. Large effect sizes and clinically meaningful symptom improvement are generally observed as a result of TFPT (Mavranezouli 2020a, 2020b). However, some individuals do not engage in TFPT (i.e. do not start therapy); a small number of individuals drop out (Simmons 2021); and a substantial number retain a PTSD diagnosis (Cusack Reference Cusack, Jonas and Forneris2016) or high levels of symptoms (Larsen 2019) at the end of TFPT. In my clinical experience, trauma processing is a one-way street such that PTSDs do not return if they have been fully processed – unless an individual's life circumstances change such that they once again no longer perceive they are post-trauma. Definitions of what constitutes ‘permanent’ PTSD or impairment differ (e.g. 5+ years’ duration) across contexts.

Trauma-focused psychological interventions – which involve elements of processing trauma memories and altering problematic trauma-related cognitions – are superior to non-trauma-focused interventions (Coventry Reference Coventry, Meader and Melton2020; Mavranezouli 2020a, 2020b). TFPT is typically delivered weekly, although it can be delivered more intensively (e.g. daily; Ehlers Reference Ehlers, Hackmann and Grey2014; Bongaerts Reference Bongaerts, Voorendonk and Van Minnen2022). Typically, 6–12 sessions are required for more straightforward presentations, but more sessions may be indicated (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2018). Almost all clinical trials conducted to test the effectiveness of TFPT have not distinguished between ICD-11 PTSD and CPTSD – suggesting that TFPT is effective for both diagnoses. Meta-analyses indicate that TFPT causes reductions in comorbid mental health problems and is effective for individuals thought to have experienced ‘complex trauma’ (Coventry Reference Coventry, Meader and Melton2020); is equally effective in relation to PTSDs arising after single and multiple traumatic events (Hoppen 2023, 2024); and is effective in reducing ICD-11 CPTSD DSO symptoms (Banz Reference Banz, Stefanovic and von Boeselager2022).

Some authors suggest that a safety and stabilisation ‘phase’ is always requiredFootnote d before trauma-focused intervention (i.e. before targeting the mechanisms thought to be central to the maintenance of PTSDs; Ehlers Reference Ehlers and Clark2000; Kangaslampi 2022; Hyland 2023). There is great variability among clinicians and academics as to what constitutes ‘stabilisation’, which interventions are offered as part of a stabilisation phase, under what circumstances/for whom stabilisation is needed and whether to ever proceed beyond stabilisation work. The limited evidence available indicates that interventions with a dedicated stabilisation ‘phase’ neither improve outcomes nor reduce drop out (Oprel 2021; van vliet 2021); critics argue that this approach is an unnecessary use of clinical time and delays change (de Jongh Reference de Jongh, Resick and Zoellner2016). Anecdotally, therapists sometimes use a stabilisation phase because of their anxiety about engaging in exposure work (Waller 2009, 2016), meaning it could potentially be conceptualised as a therapist therapy-interfering behaviour.

Overall, most clinicians and academics seem to agree that TFPT should be individualised, formulation-driven and involve multiple components; should address the problems that most concern the individual experiencing PTSD (Cloitre Reference Cloitre2015); and should be delivered by a suitably trained, regulated and qualified professional who is receiving appropriate clinical supervision. Given limited evidence that a phase-based approach is superior, and uncertainty about whether a stabilisation phase is needed at all, it seems best and most ethical to seek to ameliorate PTSDs by targeting the mechanisms theorised to be central to their maintenance, rather than to help people to live with their symptoms.

Remote assessment and therapy

Working remotely became popular during the COVID-19 pandemic. It confers several advantages, including reducing geographical barriers and travel time and costs, overcoming logistical challenges in attending appointments (e.g. due to caring responsibilities or an impairing health condition) and increased convenience. The available evidence suggests that remote psychological and psychometric assessment of PTSDs and remote psychological therapy are generally comparable to working face to face in terms of effectiveness, safety and acceptability for clinicians and patients (Batastini Reference Batastini, King and Morgan2016, Reference Batastini, Paprzycki and Jones2021; Olthuis 2016; Wild 2020; Bongaerts Reference Bongaerts, Voorendonk and van Minnen2021, Reference Bongaerts, Voorendonk and Van Minnen2022). The appropriateness of remote assessments must be considered on a case-by-case basis, in collaboration with involved parties, prioritising clinical need, ethical rights and choice, and accounting for any contraindications (e.g. poor digital access/awareness, cognitive difficulties, auditory or visual impairments, severe mental health problems, high levels of risk, young age).

Accessing therapy

Many people experiencing PTSDs wait years or decades before disclosing past experiences and seeking professional help. Several barriers potentially limit access to TFPT, including lack of confidence in treatment effectiveness; fear of PTSD symptoms worsening; perceived stigma regarding psychological therapy; practical barriers (e.g. transportation, treatment availability); and long waiting times (Smith 2020).

The right time

Expert witnesses are encouraged to explicitly discuss alternative treatment options with the individuals they are assessing so that realistic recommendations and prognostic predictions can be made. It is each person's ethical right to choose whether and when they want to engage in TFPT. Although TFPT may seem indicated, it may not be the right time for an individual to engage in therapy. Crown Prosecution Service (2022) guidance on pre-trial therapy emphasises prioritising the well-being of the victim, giving informed choice regarding treatment, and not delaying therapy if it would be in the victim's best interest; the recommendations may be different outside of England and Wales. However, it can be difficult or impossible to ‘put the trauma in the past’ if current or future situational factors mean that an individual does not perceive that they are post-trauma (e.g. preoccupation with an asylum claim outcome, ongoing interviews and legal process, ongoing trauma exposure or threat).

Suicidal thoughts and psychoactive substance use are common in individuals experiencing PTSDs (Luciano 2022; Hien 2023). These, insomnia, severe distress and severe flashbacks and dissociation, are sometimes perceived as reasons to delay treatment (Murray 2022). However, these factors are not necessarily contraindications for TFPT. The relationship between PTSDs and other difficulties needs to be carefully assessed and considered. Ameliorating PTSDs often addresses other difficulties (Hien 2023; Luciano 2022; Murray 2022). PTSDs and comorbid substance use can be treated effectively by TFPT (Hien 2023). However, during TFPT individuals must not be too emotionally numbed to bring distressing trauma memories to mind; thus, an individual may be using substances in general, but should not do so for hours or days before each therapy session if this seems to be impacting progress.

Conclusions

Although PTSDs are a common, serious, complex mental health problem, a wealth of theoretical and empirical literature provides a foundation for accurate identification, assessment, understanding, diagnosis and treatment. Careful, comprehensive assessment can usefully benefit the courts and individuals experiencing PTSDs.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2024.27.

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

Owing to space constraints, the reference list is continued in the Supplementary material, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2024.27.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 As regards the relationship between trauma and PTSDs:

a PTSDs can develop in relation to events that cannot be recalled (e.g. due to head injury)

b PTSDs can develop following events that did not physically occur (e.g. hallucinations due to psychosis or intensive care experiences)

c PTSD is not more likely to follow traumatic events defined by DSM-5-TR Criterion A than non-Criterion A stressors

d how best to define and understand what is and is not ‘traumatic’ and whether and how to include trauma exposure as a diagnostic criterion for PTSDs have been long debated

e all of the above hold true.

2 An ICD-11 diagnosis of CPTSD entails:

a exposure to an extremely threatening or horrific event or series of events, plus one or more of each of the following symptom types: re-experiencing in the present, avoidance, and sense of threat, with associated functional impairment

b one or more symptoms of re-experiencing in the present and sense of threat, with associated functional impairment

c exposure to an extremely threatening or horrific event or series of events, plus one or more of each of the following symptom types: re-experiencing in the present, avoidance, sense of threat, affect dysregulation, negative self-concept and disturbances in relationships, which persist for at least several weeks, with associated functional impairment

d exposure to an extremely threatening or horrific event or series of events, plus one or more of the following symptom types: re-experiencing in the present, avoidance, sense of threat, affect dysregulation, negative self-concept and disturbances in relationships, with associated functional impairment

e one or more of each of the following symptom types: re-experiencing in the present, avoidance, sense of threat, affect dysregulation, negative self-concept and disturbances in relationships, with associated functional impairment.

3 A DSM-5-TR PTSD diagnosis entails:

a exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury or sexual violence, one or more ‘re-experiencing’ symptoms, one or more ‘avoidance’ symptoms, two or more ‘negative alterations in cognitions and mood’ symptoms, two or more ‘marked alterations in arousal and reactivity’ symptoms, and that the symptoms persist for more than 1 month and cause clinically significant distress or functional impairment

b exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury or sexual violence, plus one or more ‘re-experiencing’ and ‘avoidance’ symptoms, and that the symptoms persist for more than 1 month and cause clinically significant distress or functional impairment

c one or more ‘re-experiencing’ symptoms, one or more ‘avoidance’ symptoms, two or more ‘negative alterations in cognitions and mood’ symptoms, two or more ‘marked alterations in arousal and reactivity’ symptoms, and that the symptoms persist for more than 1 month and cause clinically significant distress or functional impairment

d exposure to actual or threatened death, one or more ‘re-experiencing’ symptoms, one or more ‘avoidance’ symptoms, one or more ‘negative alterations in cognitions and mood’ symptoms, one or more ‘marked alterations in arousal and reactivity’ symptoms, and that the symptoms persist for more than 1 month and cause clinically significant distress or functional impairment

e exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury or sexual violence, one or more ‘re-experiencing’ symptoms, one or more ‘avoidance’ symptoms, one or more ‘negative alterations in cognitions and mood’ symptoms, and two or more ‘marked alterations in arousal and reactivity’ symptoms.

4 The literature on PTSDs demonstrates that:

a PTSDs do not predict worse educational and occupational performance and outcomes

b PTSDs are characterised by deficits in various neuropsychological abilities, which are similar irrespective of the type of the trauma experienced

c the deficits in various neuropsychological abilities are different depending on the type of trauma experienced

d there is robust and reliable evidence that a safety and stabilisation ‘phase’ is necessary before exposure to traumatic memories and meaning-making, the mechanisms thought to be central to explaining PTSDs

e remote assessments of PTSDs and remote psychological therapy are generally less effective, safe and acceptable for clinicians and patients than face-to-face working.

5 The evidence-base indicates that:

a some medications have a small positive effect on PTSD symptoms

b large effect sizes are generally observed as a result of trauma-focused psychological therapy

c trauma-focused psychological therapy causes reductions in comorbid mental health problems; is equally effective in relation to PTSDs arising after single and multiple events; and is effective in reducing ‘disturbances of self-organisation’ symptoms in ICD-11 CPTSD

d although trauma-focused psychological therapy may seem indicated, it may not be the right time for an individual to engage in therapy

e all of the above hold true.

MCQ answers

1 e 2 c 3 a 4 b 5 e

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.