In this article, I will discuss how, why and to what ends agricultural science became a favoured topic in communications directed to the young in early twentieth-century Portugal. My argument revolves around seven novels on agricultural subjects, written for young people, by the agricultural engineer João Coelho da Motta Prego (1859–1931), when Portugal faced a huge economic and financial crisis, and published when the country became a republic (5 October 1910). Prego's novels for young people covered horticulture, poultry farming, beekeeping, dairy farming, silkworm breeding, orchard culture and fish farming. These novels crowned sixteen years of sustained campaigning in the daily press on agricultural matters, by Prego, during the last two decades of the constitutional monarchy. The novels cannot be understood without a broader appreciation of both Prego's life and the political, economic and financial problems that Portugal faced at the time. This article will attempt to highlight the significance of Prego's novels for young people in the context of early twentieth-century Portugal and further discuss its implications.

Agricultural science has its own historiographical field. However, from the point of view of science popularization/popular science, agricultural science may turn out to be an interesting field to explore within the history of science. At the turn of the twentieth century, most of the world's population lived in the countryside and earned their living from agriculture, England being an exception. The slowly changing late nineteenth-century Portuguese landscape consisted mainly of small rural communities over which two migration-attracting cities towered: the capital, Lisbon, and Oporto in the north. In Portugal, at the end of the nineteenth century, small properties predominated in the mountainous north-western areas while modern, mechanized farming dominated the landscape of the southern plains. Modernizing agriculture had long been a part of the emerging liberal order's political agenda. However, the country's structural shortage of raw materials, its small internal market and hamstrung industrial growth at the turn of the century still underpinned the view that agriculture was the key sector to invest in.Footnote 1 Although the growth rate of industrial production was almost four times that of agriculture, in 1910 agriculture still overshadowed manufacturing. It represented 70 per cent of exports and 37 per cent of gross domestic product, and employed around 60 per cent of the labour force.Footnote 2 As such, the daily press often addressed agricultural matters. The lobbying/educational agenda conveyed by Prego in the daily press and in his novels is a case in point.

The low cost of newspapers made them the preferred medium to reach the population at large and, for that reason, a number of studies have emerged in recent years within the STEP initiative,Footnote 3 to learn how, outside the traditional Western zone (i.e. Britain, France, Germany and the United States), science (or rather science, technology and medicine – STMFootnote 4) was communicated to the population; what drove the popularizers, the newspapers and the journalists to write about a certain topic; what were readers’ interests; and what sort of social and economic implications were associated with popularization.Footnote 5 These studies rekindled interest in popular science and the popularization of science by showing its usefulness in probing deeper into science as a constituent of modern societies. From a historiographical point of view, this article brings together often neglected sources and themes within history of science: daily newspapers, agricultural science and science for young people, all of which can further enrich the understanding of how science circulated within society at large. And in doing so, it hopes to further contribute to the historiographical debates associated with the usefulness of the concepts of science popularization/popular science to understand and study the circulation of knowledge and its implications.Footnote 6 In fact, in this article, popularization of agriculture in the daily press turned out to be a useful primary source to understand the way science was communicated to a lay audience at the turn of the twentieth-century in Portugal, and to understand the context of production of Prego's novels for young people.

This study thus stands in contrast to those within the scholarship on science popularization/popular science that have mostly targeted urban audiences in rich and highly industrialized countries of the Western world, where science in the daily press has barely been addressed. Moreover, science for young people has been mostly studied during the Victorian era,Footnote 7 and books on agriculture for the young tend to be dealt with within the wider study of institutional teaching and learning practices, such as nature studies and agricultural education.Footnote 8 As has already been shown elsewhere, science popularization/popular science was used as an educational tool.Footnote 9 In the case under study, I show that a set of popular novels on agriculture directed at young people, which were in line with the elementary agriculture syllabus but were not textbooks, clearly served the purpose of re-educating the rural inhabitant and reviving the Portuguese agriculture-based economy. This re-educational agenda, I argue, involved more than merely instructional or vocational education. It was meant to refashion the poor, rural, Portuguese inhabitant to become a full citizen of a liberal economy. Only then could Portugal be lifted to the level of the wealthy nations. For that reason, there is an implicit taming of the impoverished populations in the way the novels are constructed.

How did locality drive and shape the way science was addressed in popular books for young people? What moral and educational agendas were imposed on what was written? What aspects of science were communicated? Who wrote for whom and why? What was the purpose of the writing itself? With this set of questions in mind, this article hopes to contribute by establishing a ground for comparison to other countries and by helping bring to the fore what lay behind popular science for young people, namely its importance for the construction of what it was to be a citizen of a nation. Finally, in line with studies showing how the social, cultural, political and economic contexts shape the way science is communicated to the public, this article aims to open up new discussions concerning the far-reaching role of science popularization/popular science in different contexts.

Prego's novels for young people

Despite all earlier attempts, magazines dedicated to children only started to appear consistently in the last two decades of the nineteenth century, while books for young people by Portuguese authors only began to come out at the turn of the twentieth century.Footnote 10 Although periodicals for children boomed at the time, they were short-lived and the number of titles available at the turn of the century remained small.

The first writings for children and young people consisted basically of compilations of translations (the stories by the French author Emile Desbeaux being an example), sometimes intertwined with Portuguese originals. Reflecting the increasing levels of literacy in cities and the foundation of schools designed to train primary teachers in 1860s Lisbon,Footnote 11 writings by Portuguese authors became more prominent from the 1870s onwards. Portuguese authors often used illustrated fantasy stories and folk tales, written in rhyme, to pass on moral virtues such as obedience and filial love, fear of God, charity, resignation to fate and destiny, and hard work and studiousness. Poverty, orphanhood and child mortality were also featured, mirroring ongoing social problems in cities.

Occasionally, textbooks and leisure books for children featured translated texts on science and object lessons. This was particularly the case in the late nineteenth century, when periodicals aimed to ‘familiarize children from early in their intellectual life with scientific and moral truths’ and ‘to disseminate useful knowledge and extol the moral virtues which are the unvarying fruitful foundations of all systems and civilizations’.Footnote 12 A closer look at the plots shows that, as everywhere else around the Western world, most of the stories targeted the relatively small, urban, upper class. Prego's novels for young people, however, featured exclusively Portuguese characters and countryside plots. They portrayed mostly impoverished children, improving their lives by way of science and technology. This was a novelty. Through his novels, Prego offered solutions for pressing livelihood problems and showed how, in one fell swoop, it was possible to redress the trade balance and revitalize rural populations while maintaining traditional order. Through them, I argue, he showed the way to include the poor, rural populations in the fabric of a liberal economy.

Prego (1859–1931) was a middle-aged man and a fairly well-known agronomist and technical writer by the time he published his novels for young people around 1910. Between 1891 and 1907, he had contributed over two hundred pieces on agronomy and agricultural policies to agricultural journals and to national daily and local conservative newspapers.Footnote 13 He also wrote a handful of technical books addressing the use of fertilizers, dairy production and wine and olive oil making. In his newspaper articles, Prego vividly reported his impressions about the laboratories, agronomic stations and experimental fields he had visited across Europe, often on official missions, and used them to reflect on the overall state of Portuguese agriculture.Footnote 14 In this respect, Prego was part of a wider movement in which late nineteenth-century Portuguese engineers were sent abroad to gain technical expertise and learn the best practices in order to implement them at home upon their return.Footnote 15 In his press pieces, Prego blamed successive governments for not agreeing over the implementation of a full package of measures in all areas of agriculture, such as those taken by other equally small and/or rural countries, like Denmark and Italy, which could bring forth a new level of economic prosperity.Footnote 16 After years of voicing his concerns and ideas to adults in the press, he turned to the young: it was left to them to regenerate the country.

Prego's novels for young people were in line with his technical books and recommendations in newspapers, and addressed the themes of economically significant crops and agribusinesses. For instance, A horta do Tomé gave thorough advice on chemical and organic fertilization, a hot topic at the time, to which Prego contributed with two technical books. Portuguese agronomists believed that chemical fertilization alone would be sufficient to increase yield and promote Portugal's food self-sufficiency, particularly in cereals. To be sure, his technical books on fertilizers sold out readily. In his press pieces, Prego also reported his own experiments with fertilizers.Footnote 17 Through them he showed farmers how they should compare different fertilization formulae.

It was while on one of his official missions, to the Madeira Islands, in 1905, that it seems Prego began writing his novels for young people.Footnote 18 Published for the first time between 1909 and 1912, they covered horticulture (A horta do Tomé (Tomé’s Kitchen Garden)),Footnote 19 poultry farming (A quinta do Diabo (Devils’ Farm)),Footnote 20 beekeeping (O padre Roque (Father Roque)),Footnote 21 dairy farming (A leitaria da Rosalina (Rosalina's Dairy)),Footnote 22 silkworm breeding (Os netos do Nicolau (Nicolau's Grandchildren)),Footnote 23 orchard culture (O pomar do Adrião (Adrião's Orchard))Footnote 24 and fish farming (A lagoa de Donim (The Pond in Donim)).Footnote 25 The stories also delved into post-primary agricultural-school curriculaFootnote 26 and the primary-school curriculum, in place since 1902,Footnote 27 to which Prego contributed with a manual on agriculture, in 1910.Footnote 28 A quinta do Diabo and O padre Roque were awarded a golden prize at an agricultural exhibition in 1911.Footnote 29

A horta do Tomé and A quinta do Diabo are written in the form of a dialogue, spiced with anecdotes; the others are slightly more literary. O padre Roque and A lagoa de Donim can arguably be considered fit for older people. But mostly it is educated young people, around twelve, both rich and poor, who are the literary agents of change and social regeneration. Published in a pocket-book format (12.5 × 19 cm), ranging from around 250 to 350 pages, and divided in small chapters (six to ten pages), Prego's novels are essentially instructive manuals for young people and even adults. The stories unfold chronologically and last for several years as the children grow up. The traditional pedagogical format of the teacher–pupil dialogue is sometimes used, but often the reader learns about farming methods through actions performed by the children. In his books, Prego diverts away from the much-criticized theoretical teaching, staging instead very concrete actions to attain a determined goal: to establish and consolidate a family agribusiness. For instance, in A horta do Tomé, the story accompanies vegetable planting and the thirty-two chapters are titled according to months. In each chapter, the children perform some agricultural practice. In all, detailed, step-by-step, time-bound management instructions are interwoven with colourful, entertaining episodes. Moreover, the novels complement each other by making reference to practices presented in one or another. Instead of presenting science facts and scientific explanations, Prego used science as a working methodology. He recommended to his readers that they should experiment, record and take notes after studying the subject in books and consulting with someone experienced – humbleness comes with the inquisitive mind. However, learning is clearly staged as a practice performed by children often only with one another.

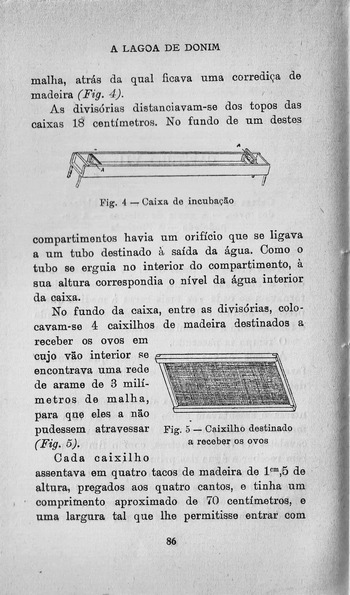

In order to make a successful venture, recording the results was as important as keeping accounts. In the novels, the text always carries cost and yield calculations, keeping in mind that the final goal is selling a product and making a profit. This preoccupation was already present in his press pieces, where Prego described minutely what he learned about olive oil production and cheese making on his trips.Footnote 30 There, he went into great detail on practical issues involving all stages of the production chain, from the field to the factory, including commercial and marketing advice. Dairies and olive oil mills equipped with modern technology were created following his endeavours.Footnote 31 He travelled around Portugal as well, to learn about local land usage and to study traditional cheese making for comparative studies.Footnote 32 For his novels, Prego took advantage of catalogues he collected during his trips, to present his young readers with modern machinery for small-scale businesses. Except for O padre Roque, in which beekeeping illustrations feature in an appendix at the end of the book, the other novels featured all sorts of illustrations enmeshed with the text, including new vegetable varieties, meeting the taste of the emerging French-influenced bourgeoisie; fertilizer formulae; pruning systems; exotic varieties of fowl; bovine breeds; types of tank fish; feed nutrition tables; incubators and all sorts of beekeeping material; pasteurizers and all sorts of cheese- and butter-making material and equipment; diseases, pests and ways to fight them; microscopes and microscopic slides; and even graphic drawings with detailed measures for building wooden equipment and facilities (see Figures 1–11). His novels also examined the role of spoilage microorganisms and pathogens, and hence the importance of hygiene to avoid diseases and produce quality products. The Dutch-style kitchen, for instance, was described as the most perfectly sanitized place to produce cheese.Footnote 33 Now and then, Prego explained more complicated matters, such as plant physiology or the ongoing acute deforestation, which had a lasting and devastating effect on river courses.Footnote 34 In all, the message that science allowed for the greater good of mankind through progress was a constant reminder.Footnote 35 Furthermore, this message dovetailed with Saint-Simonian and positivist ideals of contemporary engineers.Footnote 36

Figure 1. Brussels sprouts. João da Motta Prego, A horta do Tomé, Lisbon: Livraria Clássica Editora de A.M. Teixeira, 1909, from Isabel Zilhão's private collection.

Figure 2. Different formative pruning techniques. João da Motta Prego, O pomar de Adrião, Lisbon: Livraria Aillaud, Alves, & Cia, 1913, from Isabel Zilhão's private collection.

Figure 3. Houdan chicken. João da Motta Prego, A quinta do Diabo, Lisbon: Livraria Clássica Editora de A.M. Teixeira, 1909, from Isabel Zilhão's private collection.

Figure 4. Bretonne cow. João da Motta Prego, A leitaria da Rosalina, Lisbon: Livraria Aillaud, Alves, & Cia, 1911, from Isabel Zilhão's private collection.

Figure 5. Schematic drawing of a fish tank. João da Motta Prego, A lagoa de Donim, Lisbon: Aillaud, Alves & Cia, 1913, from Isabel Zilhão's private collection.

Figure 6. Feed nutrition table for chickens. João da Motta Prego, A quinta do Diabo, op. cit.

Figure 7. Honey extractor. João da Motta Prego, O padre Roque, Lisbon: Livraria Clássica Editora de A.M. Teixeira, 1911, from Isabel Zilhão's private collection.

Figure 8. Pasteurizer. João da Motta Prego, A leitaria da Rosalina, op. cit.

Figure 9. Honey bee pests. João da Motta Prego, O padre Roque, op. cit.

Figure 10. Microscopic slide showing pébrine corpuscles (spores). João da Motta Prego, Os netos do Nicolau, Lisbon: Livraria Clássica Editora de A.M. Teixeira, 1912, from Isabel Zilhão's private collection.

Figure 11. Fish incubator box. The text explains how to build one and set several in a row. João da Motta Prego, A lagoa de Donim, op. cit.

The novel Os netos do Nicolau is a good example of Prego's plots and mindset. It touches on many problems pertaining to social and economic aspects of Portuguese life and on how Prego proposed to solve them. As the story goes, Nicolau's impoverished family owned a two-century-old, outdated cutlery and a phylloxera-devastated vineyard in the surroundings of Guimarães, Prego's home city, situated in the densely populated north-western Minho region. In view of their financial situation, Nicolau's elder grandson decided to set up a silkworm breeding house as an alternative family business, after being offered a book on the topic on School Day. In the story, Nicolau was an educated, low-ranking soldier who had fought alongside liberals during the Patuleia civil war, back in 1846 – a major popular upheaval against taxes. But it is Nicolau's grandchildren who are the main characters of the plot. Nicolau's elder grandson benefited from various local government infrastructure as he set up his silkworm breeding house. The boy travelled to another town by train to learn from an experienced breeder and took lessons at a government-run silkworm breeding practical school. Backed by his former primary teacher and the local municipal laboratory, he built and equipped a silkworm breeding house, step by step. The family was happy when the penniless, emigrant father managed to modernize his ancestors’ cutlery, with the money his children had set aside, which belonged to all, equally. The family's happiness eventually spread to the town and country. Because the boy unselfishly taught his city folk silkworm breeding, the town became a balanced industrial centre of small-scale producers and households, with an evenly distributed income. The cycle was closed by local manufacturers who purchased the town's output. As Prego pointed out, silkworm breeding ‘is not an industry fit for the rich. But it is an industry that might be beneficial for the poor’.Footnote 37 Powerless, impoverished populations were thus encouraged to comply with the established class structure. As one big family, local producers and manufacturers cooperated instead of competing, each knowing that their role would help the country redress its trade balance – a key point in other novels as well.

The offering of books during School Day is not incidental in the novel. School Day was a late nineteenth-century practice, officially adopted at the turn of the century.Footnote 38 Two of Prego's novels – A horta do Tomé and A quinta do Diabo – were approved by the government in 1908 to be offered to the best elementary-school pupils on School Day, a fact proudly announced on the cover. In Prego's novels, activities were made possible by local, government-run farms, practical schools and books awarded on School Day. In this way, Prego demonstrated to young people how they could use the books received at the end of their studies to kick-start their working life and contribute to the household income. At the same time, the plots fictionalized existing infrastructure, agricultural policies and educational reforms enmeshed with others that Prego wished to see implemented in Portugal. Prego thus claimed to overturn traditional rural views that the state's sole purpose was to collect tax.

In Os netos do Nicolau, School Day was perfectly timed to coincide with the renewal of silk production in Portugal. School Day was celebrated with great flair during springtime and, from 1908 onwards, it started to entail tree planting. Preferred trees included white mulberries, once widely cultivated in Portugal for silk production. However, by 1875, silkworm breeding, battered by pébrine, had decreased sharply, while state efforts to control the disease were held back by the economic impact of the spread of phylloxera in vineyards. Yet small domestic industries remained active and the government eventually took measures to revive silkworm breeding, including setting up a dedicated station in the north-east in 1891, which was later converted into an undifferentiated local agriculture station in 1898.Footnote 39 There, cocoons were bred using Pasteur's methods and were quality-assured by female hands.Footnote 40 Silkworm breeding required a relatively small initial investment and could provide a sound alternative business line to penniless people, otherwise forced to emigrate, as had been the case with the father of Nicolau's grandchildren. And, in fact, the government distributed cocoons and mulberries free of charge to farmers willing to resell their harvest to local government-run agricultural farms and stations.Footnote 41 This was exactly what Prego plotted in Os netos do Nicolau. In 1912 the Século Agrícola (Farming Century) weekly magazine (to which Prego contributed some articles), owned by the influential nationwide Século newspaper's publishing company, came up with the idea of organizing a School Day to plant mulberry trees all over Portugal.Footnote 42 Farmers and agronomy professors wrote to the press, rallying behind this idea.Footnote 43 The event was a success. Published for the first time in 1912, Os netos do Nicolau was perfectly timed with the event. In Prego's own words, silkworm breeding was an opportunity both for small farmers to recover lost ground and for the country to avoid currency outflows from importing raw silk.Footnote 44

The preoccupation with currency outflows had a reason. By the time Prego began writing in newspapers, in June 1891, the Portuguese Treasury was succumbing to pressing cash flow issues. The financial crisis ended the period known as the Regeneração (‘Regeneration’, 1851–1890).Footnote 45 Regeneração embodied the renovation of the political system, the reform of the Central Administration promoted by engineers moulded on Henri de Saint-Simon's ideals of efficiency and meritocracy,Footnote 46 and the construction of infrastructure. The building of three thousand kilometres of railway lines and fifteen thousand kilometres of macadam roads between 1850 and 1910 changed the country's landscape irreversibly.Footnote 47 The huge public investment was only made possible with money borrowed from abroad – a decision that proved fatal in 1891. Many factors contributed to the incapacity to pay for the public debt, namely the loss of revenue from wine exports and lower remittances from Brazil, both reflecting the structural weakness of the Portuguese economy.Footnote 48 Up until 1902, international borrowing was hampered by a partial state bankruptcy, declared in 1892. Drained of its gold reserves, the state had to live on non-convertible fiat money for the next ten years. At the same time, rising import duties opened up new prospects for domestic industries and agricultural production, a situation that Prego explored and advertised in the plots of his novels, of which Os netos do Nicolau is a good example. In this sense, the novels are more than just a story about how to make use of the books received on School Day. The stories offered a way out of the crisis Portugal faced at the time, even showing how to make good use of state infrastructure investment. The infrastructure included the railway and, as recently as 1886, a full package of laws designed to reorganize and modernize agricultural services and institutions. The 1886 agricultural policies were very dear to Prego and kick-started his career.Footnote 49And in the years that followed the 1891 crisis, he would campaign for the application of 1886 agricultural policies in the daily press.Footnote 50 Amongst other measures, it provided for the creation of agricultural research stations in twelve agronomic districts, as well as a network of government-run practical schools for male rural workers aged fourteen to eighteen who held a primary-school certificate, in order to counterbalance the hitherto small number of government-sponsored, but privately run, short-lived agricultural practical schools.Footnote 51 But the 1891 crisis forced adjustments.Footnote 52 Of the six agricultural research stations actually created, only the ones in Lisbon and Oporto were in place by 1892. By 1906 their number had risen to three, but except for Lisbon's the other two were mere laboratories.Footnote 53 Over the next few years a clearly insufficient number of agricultural practical schools, some of which were short-lived, including dairy schools, were put in place.Footnote 54 In 1891, some of these schools were either dismantled or rented for dairy production.Footnote 55 In 1899, the remaining government-run agricultural practical schools were closed down.Footnote 56 Of the original project, only the two schools offering secondary education in agriculture remained in place. The net result was that, during the entire period, access to agricultural education remained limited, both for the peasantry and for the rural working class.Footnote 57

Prego was highly critical of the fact that existing agricultural schools were exclusively attended by a handful of well-off boys.Footnote 58 This was a reality he knew well since between 1899 and 1904 Prego had himself taught at an agricultural secondary school, which he also directed.Footnote 59 Well aware that modern farming could not forgo knowledge and schooling, he often advocated in his press pieces investment in the creation of well-equipped practical schools close to production centres.Footnote 60 In fact, existing government-run practical schools were paid boarding schools which served their boarding population and a small number of tuition-free students.Footnote 61 In his press pieces, he underscored the educational success promoted by agricultural itinerant schools in countries such as Switzerland and Belgium.Footnote 62 The so-called Maria Christina itinerant schools, as well as an accompanying magazine, O Lavrador (Farmer), were eventually created in the north of Portugal in 1902, sponsored by a philanthropic emigrant in Brazil, and with the help of the newspaper Comércio do Porto (Commerce from Oporto).Footnote 63 Because of this, Prego's novels were essentially practical, and this practicality was not incidental. The hands-on-approach was generally considered to be absent from Portuguese classrooms. In his novels, Prego often pointed out the advantages of object lessons and the intuitive learning method for teaching in practical and itinerant schools. Also, some of the agricultural tools and equipment the author speaks of were available in the agricultural schools, notably dairy, and at the local government-run farms, where farmers could see how the equipment worked.Footnote 64

Similarly, investment in primary education in general remained modest, despite legislation. Successive monarchic governments had not been able to tackle this problem, although they generally recognized that it hampered the country's progress and industrialization. But persistent illiteracy (69 per cent for those aged ten or over in 1911) was a compound problem.Footnote 65 Even if inland primary schools were sparse, schooling was not always regarded as an important goal in life, especially by those parents who lived on subsistence farming and livestock grazing. Realizing how difficult it would be to get through to the rural population on this, Prego aimed instead to entice educated young people, raised in the city, to move back to the countryside and, once there, to lead by example. Furthermore, even as he presented the benefits of getting a proper education, Prego still offered a solution to parents who, out of necessity, were unable to send all their children to school. In Os netos do Nicolau, for instance, Nicolau's grandson trained his younger sisters in the business, while teaching them the alphabet (the boy would later become a primary teacher). In the same vein, three other novels, A horta do Tomé, A quinta do Diabo and A leitaria da Rosalina, portray a poor family with many children, in which the eldest are responsible for teaching the alphabet to their younger siblings. In all of them, these were excused from going to school on account of the new family business. Prego thus recognized the necessity, at the time, of child labour in poor families. Nevertheless, this could be mitigated by home schooling. Again, Prego proposed the establishment of practical itinerant schools, instead of the former paid boarding schools, which hardly served the poor rural population, as invaluable places where young protagonists learned about their new trade. Prego thus depicted youngsters who generally studied in itinerant schools and developed their businesses at home, with their family.

Family love was essential in the unfolding of all the stories, where parents and relatives were portrayed as caring and supportive people. In Os netos do Nicolau, the building of family and community cohesion permitted also the overcoming of emigration problems in Guimarães. The city lies at the foot of a centuries-old pilgrimage site in the Minho region, which has long been characterized by a range of scattered villages and small farms. Excessive land partitioning in this region, caused by how land was inherited, forced many men to emigrate. The low demand for labour and the increasing prices that followed the 1891 crisis forced many more to flee to the cities, or emigrate to Brazil or North America. The region is also renowned for its textiles, leather and cutlery industries, which made it an important manufacturing centre at the turn of the twentieth century. But competition with the cutlery industry ruined small manufacturing, forcing more men to emigrate.Footnote 66 As we have seen, it was Nicolau's grandchildren's efforts that saved their father's business and not their father's emigration, which was a failure. In addition, Guimarães has a deep historical significance. The Christian Reconquista has been historically portrayed as having started from there at the hands of Afonso I of Portugal in the twelfth century. This lends a symbolic refounding, ‘regenerating’ purpose to Prego's novels, the majority of which are set on the outskirts of Guimarães.

The sense of community surfaced again in A leitaria da Rosalina with even deeper implications, and this novel is probably the most uncompromising of all. The story is about how, thanks to Rosalina – an educated and city-bred girl – an entire village became a balanced dairy production centre. Rosalina expanded her dairy and farm by purchasing local church-confiscated property at a public auction, with the help of a rich immigrant uncle. With the money she had set aside from selling cheese, she built a fully equipped dairy and promoted a well-established market in the city of Oporto, situated in the north. Local illiterate peasants, who only drank milk as medicine, mortgaged their land to make modest investments.Footnote 67 In the end, a Minho village was spared from emigration as it moved from charcoal kilning and subsistence farming to French-style cheese making and well-cultivated and fertilized farms, thus entering the producer–consumer paradigm. By transforming inland populations into producers and consumers, Prego offered not only a way to expand both the Portuguese internal and external markets but also a way to prevent the outflow of currency caused by the importation of goods. In fact, Portugal had been losing agricultural export markets to the rest of the world: eggs and butter to Denmark; wine and olive oil to France and Italy; silk to France; silk, fruit and horticulture products to non-European countries; and beef cattle to South America.Footnote 68 At the same time, cooperatives offered a way to overcome the lack of subsidies and the high cost of capital, two issues that Prego complained about in his press pieces.Footnote 69 Prego had been greatly impressed with the improvements in rural life promoted by agricultural associations that he saw abroad. Dairy cooperatives, in Prego's view, proved successful economic ventures in Denmark and in the north of Italy and he used them in the newspapers as examples to show sceptical Portuguese farmers the benefits of association.Footnote 70 In fact, in Portugal it was generally acknowledged at the time that the Portuguese had a low appetite for business associations.Footnote 71 He campaigned firmly for the creation of agricultural associations in Portugal and eventually founded one, in 1897.Footnote 72 In 1915 he became the director of a dairy cooperative.Footnote 73 Arguably, the cooperative in the story may have served a dual purpose: while it improved everyone's life and demonstrated the usefulness of association in business, it showed how the community could continue under liberalism. In fact, major land reform was undertaken after the first liberal revolution, in 1820. Male monastic orders were extinguished and expelled from the country. Confiscated land was auctioned but old aristocrats, more recent members of the nobility, politicians and public clerks were the ones who actually profited from the sale. From 1869 onwards, communal property and parish land were confiscated and put on the market, in order to make more land available for agriculture.Footnote 74 In the end, much of the land remained underused or completely unused, while many of its owners lived in cities. Ousted from communal land, the majority of the non-gentry rural population survived on subsistence farming, barter, seasonal work on large estates and occasional work in small industries.Footnote 75 Rosalina's purchasing of land expropriated from the local clergy to expand her farm and create a cooperative both restored the community underlying the confiscated communal propriety and extended the liberal ideal of ownership to all, and by extension citizenship. In fact, only private property – or private income – or education would turn male individuals truly free, and hence full citizens, with voting rights.Footnote 76 In time, earned income and education would transform inland peasants and farmers into full and satisfied citizens of a liberal economy, and eventually lift Portugal to the level of wealthy nations.

The class reconciliation reached at the end of the novel Os netos do Nicolau is also evident in the way Prego depicted landlords living in the city. He portrayed absent landlords as good men who suffered greatly from anaemia and tuberculosis, caused by the city life, as in O pomar de Adrião. By showing them the benefits of living closer to nature, Prego urged their younger people to change their attitude. In fact, Prego believed that the rich landowners’ trading of the dusty countryside for the sparkling city compromised agricultural progress, and he often voiced this view in the press: they offered the sad spectacle of a dissolute lifestyle and vast expanses of underused land.Footnote 77 Again, Prego stages his idealizations in the novels, O pomar de Adrião being a case in point. Featuring the ‘ill-advised’ king as a character, O pomar de Adrião has as its protagonist Counsellor Adrião's son. Counsellor Adrião was an important member of the government who led a tiresome political life at the capital and who, because of that, was rarely present at his estates. After realizing the effect that politics had on his father, the boy chose to expand his family farm rather than be sent to a junior boarding school to continue with his studies. Clearly, here there was an implicit social critique of the upper class who chased after a university degree merely to attain status in the city. The expansion of the farm was again achieved by the purchase of local land, confiscated from the clergy. Guided by books and his uncle, a farmer, and with the help of the local government agronomist, the eleven-year-old boy set up an orchard for market-oriented fruit and jam production. The end of the novel – his worn-out father dying by his side amid blossoming fields – is testament to the resurrection of a regime at the hand of a renewed generation of local influential farmers. In the novel, Prego stated his belief that the Portuguese private sector could improve the life of everyone and help the country out of its financial difficulties, if only it was led by experts and well-informed landowners, supported by government agencies, located close to production centres. Prego himself put his ideas into practice on many occasions, demonstrating the benefits of fertilizers to illiterate farmers, helping them out at the local farming association, or even showing around olive oil mill equipment, and giving advice after Mass.Footnote 78 To honour his ‘extension’ work, a Prego bust was erected next to that of Veríssimo de Almeida (considered to be the founder of agronomy in Portugal) at the Agronomic Institute of Lisbon.Footnote 79 And he was awarded the Grand Cross of Agricultural Merit only three months before his death, in July 1931.

Prego would later revisit the theme of generational turnover among rich farmers in A lagoa de Donim. This novel focuses on a ruined young aristocrat who decided to leave his unproductive city life and return to his ancestors’ estates to set up a freshwater fish farm. In this novel, as in Os netos do Nicolau and O pomar de Adrião, Prego discussed a reality that was close to him: all are set in the vicinities of his family estates. Notably, Donim is Prego's forefathers’ estate and the author himself conducted experiments on freshwater fish farming there.Footnote 80 Actually, Prego was born into the Guimarães rural aristocracy,Footnote 81 and his family owned extensive properties there. A lagoa de Donim is also full of ethnographic details that bear witness to Prego's membership of the Sociedade Martins Sarmento, located in Guimarães and dedicated to archaeology, history and ethnography.Footnote 82 In A lagoa de Donim, books and the government-run aquaculture station's supplying of fish are again key to the success of the business. In the end, the young man married the daughter of a hard-working local farmer who had contributed significantly to the country's wealth: ‘Those in charge nowadays are the ones who work honestly, those who have arms and intelligence to rise up from the earth on their own.’Footnote 83 The marriage between old aristocracy and emerging landowners exemplifies the repopulation of the countryside with ‘quality’ seed. The message that the only wealth worth having is the one earned through hard work is a recurrent one in his novels and goes hand in hand with the critical remarks he made in the press. There, Prego drew attention to the many rural folk he came across during his trips abroad, as role models for Portuguese farmers. For instance, he described how a major Tuscan farmer was, nevertheless, a simple and modest man, working side by side with his workers; or how this man's daughter lived on the family farm and attended the local elementary school together with his workers’ children.Footnote 84

By the same token, enriched emigrants often chose to mimic aristocrats rather than invest in their home town. Along the same lines, the role of emigrants in the economic uplift of rural communities is often discussed. In O padre Roque, an emigrant donates an institute consisting of a primary school and an associated arts and crafts workshop, and a museum featuring an object lessons section. The endowment of the private school is set as an example to be followed by other enriched emigrants, to help cope with the short supply of schools at the time. In A leitaria da Rosalina is the rich emigrant uncle who helps her to buy the land she needs to kick-start the dairy. In Os netos do Nicolau Prego shows the other side of emigration, the many more that never succeed to make a fortune, sometimes never to return home. In the novel, we learn, wealth should be sought in one's home town, not abroad.

Religious reconciliation is present in the stories as well. Well aware of the Catholic Church's influence on rural populations, Prego suggested after-Mass farming lectures by local priests as an ideal popularization vehicle to reach the population at large. He also advocated the idea of delivering agricultural lessons to men during conscription. In A leitaria da Rosalina, Rosalina's father benefits from lessons of this sort at the military barracks with great advantage to his daughter's dairy business. Prego had learned about both in Italy.Footnote 85 Prego regarded local priests as good allies in changing outdated, but deeply rooted, farming practices. In many of his novels local priests play exactly that role. In perhaps his most moralistic and young-adult novel – O padre Roque – Prego goes one step further. He portrays a priest as the saviour of a southern smuggling village. The story demonstrates how a progressive and educated local priest turned beekeeping into a viable business activity and thus rescued his parishioners, with the help of his consumption-stricken daughter. The girl had contracted her sickness while residing in a convent. Prego used this as a means to express anti-clerical liberal ideals. In the same vein, Prego was highly critical of those priests who did not accept liberal ideas, portraying them as backward and futile, as he did with the Donim priest. Those priests represented the old regime and the monastic orders that had been expeled from the country following the liberal revolutions. However, by the end of the constitutional monarchy, religious orders devoted to teaching and healing were tolerated, despite the sometimes violent outbreaks of protest in Lisbon and Oporto.Footnote 86 Even though this is not overtly stated in the novel, the priest, imbued with a scientific spirit, personified Bernardino Barros Gomes (1839–1910),Footnote 87 the reputable scientist and forest engineer who, after his wife's death, became a Lazarist, devoted to teaching.Footnote 88 Jesuits and Lazarists in particular faced strong anti-clerical opposition from society at large, and Gomes ended up one of the few victims of the republican revolution, in 1910. Tightly woven into the story, beekeeping is inevitably used as a parable for human societal constructs. A testament to his spirit of reconciliation and fellowship, Prego repeatedly mulled over man's incapacity to orchestrate a society as balanced as that of bees.

Another interesting and original side to Prego's novels is women's role in the narrative. In all the novels, the girls have important work roles, even when they come from a higher social layer, as in O padre Roque, or as the elder sister in Os netos do Nicolau who was in charge of sorting out infected cocoons with the microscope, as women did at the north-east station. Besides, Prego regularly portrayed girls as intelligent, proactive, key characters and even successful entrepreneurs, as in A quinta do Diabo and A leitaria da Rosalina. This mindset stood in vivid contrast with the contemporary traditional views of the female gender, of which the female literacy rate of 23 per cent in 1911 (as against 40 per cent for men) reflected their disadvantaged condition.Footnote 89 Nonetheless, to him, dairy schools were places where women could learn household duties and how to become good wives, mothers and educators – their foremost goal in life: ‘Couples should be equally balanced by giving women a more important role and freeing them from the serfdom associated with ignorance and their exclusive role as servants.’Footnote 90 As Prego often pointed out in the more adult stories, women were traditionally close to the family house, therefore poultry and cheese making came as natural activities to them, a way to contribute to the economy of the household and, ultimately, of the country. His novels are clearly in line with what he wrote in the newspapers about the work role of women, ideas that might have been influenced by his visit to the Swiss educational institutes, since at the time they admitted a disproportionally higher number of women students than anywhere else.Footnote 91 Moreover, his wife, also a children's novelist, was a keen supporter of the Swiss educational system.Footnote 92 And Prego's views about schooling for women dovetailed with those expressed in the Progressive Party's law of 1906, which stated that while secondary schooling should serve mostly to educate women on how to be good mothers and wives, it should nevertheless prepare them for a profession and to be independent.Footnote 93 Besides their work role, educated girls are the ones who demonstrate the power of science in overthrowing firmly rooted superstition in the novels, A quinta do Diabo being a particular case in point. The novel is about a young girl who managed to set up a poultry farm in an otherwise unproductive ranch where cattle died off. Locals blamed the Devil for killing the animals. As the narrative unfolds, it becomes apparent that cattle are being killed by carbuncle; the girl realized this after consulting with a scientist at an institute in Lisbon. As in real life, the institute produced vaccines and had a carbuncle vaccination plan for cattle,Footnote 94 a novelty for city dwellers, let alone for rural folk. Besides urging government laboratories in place to support agriculture and rural populations, Prego was promoting scientists and science, and the possibilities they offered for solving problems. Moreover, Prego was relatively well acquainted with laboratory life. After graduating in 1887 at the Agronomic and Veterinary Science Institute, he learned soil chemistry and fertilization with Achille Muntz at the Agronomic Institute of Paris.Footnote 95 In 1894, at the Agronomic and Veterinary Science Institute, he worked as a chemical analyst and later as a demonstrator; he also started and led the institute's fermentation laboratory at least until 1895.Footnote 96 And he published journal articles on yeasts and wine fermentation.Footnote 97 Collaborative research with the institute's director afforded him membership of the Société mycologique de France.Footnote 98 Ten years later, Prego was granted membership of the Academy of Sciences.Footnote 99

Whether held in public libraries or in itinerant libraries, or housed in primary schools,Footnote 100 Prego's novels circulated during his lifetime. Print runs are impossible to find; however, a contemporary and close source stated that over 60,000 books (all his oeuvre) had been sold in Portugal and Brazil by 1919.Footnote 101 By 1931, all the novels had already been sold out.Footnote 102 They were republished in the 1940s. A horta do Tomé and A quinta do Diabo were reprinted many times in between, probably because of their approval for schools. The novels continued to be part of itinerant libraries after the Second World War. In fact, mid-twentieth-century agriculture still employed a large fraction of the Portuguese workforce. For that reason, the topic occupied a tangible place in Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian mobile libraries (1957–1987),Footnote 103 and Prego's novels were sufficiently relevant to be part of its booklist.Footnote 104 This privately run foundation has been a cultural and scientific landmark in Portugal since its founding in 1956. Its itinerant libraries in particular were created to further literacy. Over the years, Gulbenkian's itinerant libraries and its bulletin reached a large audience in Portugal.Footnote 105 The reception of Prego's novels by his readers is more difficult to grasp. It is not known whether he received letters about his novels. Contemporary memoirs were also left unexplored, though they were not a common practice at the time. Positive impressions about his novels resonate on the Internet but they are rare.Footnote 106 This paper will therefore not delve into the reception of Prego's novels.

Concluding remarks

In order to develop Portuguese agribusiness, Prego believed that the private sector should lead the economy backed by an essential set of state agricultural policies. In this respect, he quoted the conservative republican Jules Simon (1814–1896) on the title page of one of his technical books.Footnote 107 Irrespective of his monarchic or republican leanings, Prego was a liberal at heart, although a complex one. On the one hand he advanced access to education and credit in order to liberate the peasantry and poor farmers from profiteers and from dependency on local caciques, turning them, in time, into satisfied landowners and producers and consequently citizens with voting rights. On the other hand he believed it possible to do so without disturbing the existing class structure. In this, Prego most probably aligned to social Catholic movements in the north of Portugal seeking to lead and take control of the masses.Footnote 108 Also, his (apparent) contradictions may just reflect the natural unfolding of an internationally driven society based on science and technology that could no longer forgo universal access to knowledge and education and to which the ruling class, to which Prego belonged, had to adapt. In the novels, Prego tried to reconcile both worlds in order to make the transition, at least initially, acceptable for the ruling class.

Prego's novels were educationally innovative but also provocative in many different ways. Tellingly, they still reflect ongoing educational discussions about children teaching children and the effectiveness of state-sponsored vocational education. In spite of the fact that the hands-on-approach solution to learning was advanced by Prego's contemporary pedagogues and even prescribed in the preambles of educational laws, the reality was that teaching was fundamentally theoretical, relying heavily on memorization, with classes given exclusively indoors, in a classroom. Instead, Prego staged a more dynamic and less prescriptive learning methodology. He proposed a flexible way of learning according to the youngster's needs and taking advantage of his/her family context. In the novels, the young protagonist is invited to take action and seek the information he/she needs in order to achieve his/her goals. Moreover, Prego stages siblings teaching siblings the alphabet and learning with one another the agribusiness they wanted to implement, often without direct supervision of an adult. Today, children teaching children echoes the twenty-first-century experiments showing how children successfully learn with one another through computers and without the direct supervision of an adult educator.Footnote 109 Before Prego's time, the private sector proved a disaster as a promoter of vocational education. Yet Prego believed that the enlightenment and education of the private sector, as he campaigned for in the novels and in the press, would overcome past difficulties. Clearly, Prego's proposal of vocational education promoted by the private sector is again timely and much in line with current, although much challenged,Footnote 110 views that the vocational education promoted by the state has failed to meet the private sector's needs.Footnote 111

The agricultural topics addressed in Prego's novels had economic significance for Portugal. When Prego suggested production alternatives to impoverished farmers, he was trying to help his countrymen. By enticing young people to move to the countryside and develop agriculture, Prego hoped to have finally found a way to regenerate the country. Yet, in fictionalizing his political and technical proposals, Prego went one step further than simply writing farming manuals for young people. By using the popularization of science and technology to prompt rich and poor people alike, both men and women, to change their attitudes, in fact liberating them from more traditional roles, Prego demonstrated how his proposals, once put into practice, would inevitably lead to successful farming holdings and the prosperity of the country, without class struggle. Imbued with a certain paternalistic tone, I argue, Prego urged the poor to take command of their destiny and become full citizens on their own – but only to the extent that order is maintained by keeping people under control. Even if, at a certain point, Prego implied that the money that went from the rich to the poor was just a restitution,Footnote 112 all in all, in his novels, powerless, impoverished populations were tamed to comply with the liberal order. More than just teaching about science and technology, this set of popular books served to indoctrinate young Portuguese people into the fabric of a liberal economy. Locality clearly shaped the staging of the novels and the purpose of the technological solutions themselves.