Charles Darwin's Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex was suffused with questions of courtship, mating and sex.Footnote 1 Darwin's reconstruction of animal history positioned animals as vital sources of information on the development of the sexes and the mechanisms of courtship. Sexologists easily combined Darwinian with Freudian perspectives whereby homosexual desire was often rendered a sign of sex intermediacy.Footnote 2 By interpreting phylogeny as analogous to ontogeny, scientific theories of sexual development reinforced the moral authority of nature as a guide to normative sexual identity and desire.Footnote 3

As sexuality came under scientific and medical scrutiny, homoerotics subtended heterosexuality, rendering desire directed towards a member of the same sex a precursor to the capacity for normative gendered identity later in life. In the words of historian Jennifer Terry, ‘homosexual men were imagined as embodying the worst of both savages and women; while they were insatiable in their sexual pursuits and frivolously emotional, they lacked the modesty of bourgeois women and the primal strength of savage men’.Footnote 4 Evolutionary theory served rarely as a hopeful intellectual resource for sex radicals at the turn of the last century and was more often invoked in concerns over civilizational degeneration.Footnote 5 Psychically, homoeroticism was supposed to disappear as it matured into heterosexuality; evolutionarily, homosexuals were fated for extinction.Footnote 6

Over a century after Descent of Man, Joan Roughgarden and colleagues sparked a flash of angry letters to the editors of Science by claiming that Charles Darwin's theory of sexual selection could not provide an explanation for the origin of sexual differences because it assumed binary, competing sexualities in animals.Footnote 7 Sexual selection, they contended, was fatally flawed; their critics demurred. Roughgarden's hope of constructing a more inclusive evolutionary account of sexuality, without relying on the sexual stereotypes found in Darwin's ‘second’ theory, caught the attention of science studies scholars, especially those attentive to questions of sex and gender norms.Footnote 8

This paper charts the fate of evolutionary theories of homosexuality from Darwin to Roughgarden, and their entanglement with gendered sexual norms as theorized through animal models of human sexuality. I argue that when evolutionary biologists in the twentieth century used sexual selection as a tool for theorizing the evolution of homosexual behaviour – which happened only rarely – the effect of their theories was to continuously reinscribe normative heterosexuality.Footnote 9 As literary scholar Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick elegantly articulated, of the four sexual preoccupations identified by Michel Foucault as critical to understanding Victorian sensibilities (the masturbating child, the hysterical woman, sex in marriage and the medicalization of perversions), the one with real staying power turned out to be the medicalization of what came to be known as ‘sexual orientation’.Footnote 10 Sedgwick added that although ideas of homosexuality and heterosexuality are ontologically inseparable, they have never been understood as co-equal – heterosexuality as a category was defined by the exclusion of homosexuality. Thus, in the twentieth century, the seemingly ritualized and unending debates of nature and nurture took place against an unstable background of fantasies about both nature and nurture. Ideas about the sexual behaviour of animals constituted a crucial basis for theorizing (or, following Sedgwick, fantasizing) nature as normative, because evolutionary biologists’ arguments rested on a fundamental division of character and behaviours into female/feminine and male/masculine.Footnote 11 The story that follows will be familiar in that it adheres in its outlines to histories of sexuality that have highlighted the cultural assumptions wrought in medical and scientific theories that stigmatized some sexual behaviours as abnormal while lauding others as wholesome and necessary to the propagation of the human species.Footnote 12 Yet most histories of evolution do not wrestle with sexuality – even those that have taken questions of sex and gender within evolutionary theory as their main goal.Footnote 13

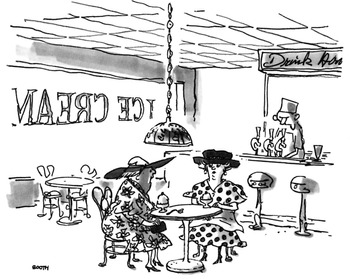

A closer look at evolutionary theories of sexuality reveals how even the biologists who found homosexuality to be a good tool to think with (like altruism) often assumed that homosexual preferences should eventually go extinct (Figure 1). (Like the sexologists, evolutionary biologists also concentrated the bulk of their intellectual attention on men.Footnote 14) Animal models of human sexuality – first based mostly on observations of animals in laboratories and zoological gardens, then based on animals in the wild – provided fertile ground for thinking about the normative implications for human behaviour.Footnote 15 Psychologists Peter Hegarty and Sean Massey have mobilized Sedgwick's distinction between universalizing and minoritizing strategies in hopes of guaranteeing same-sex rights through science. They identify two broad phases of evolutionary theorizing about homosexuality that map onto tranformations in social-psychological thought more broadly. First, through to the 1970s evolutionists imagined a homoerotic potential within all people. ‘Pathological’ behaviour in this context was assumed to manifest in adults as sexual intermediacy. Then, in the final decades of the twentieth century, biologists sought to understand homosexuality as an identity associated with only a minority of the population, baking conservative notions of gender into explanations of homosexuality as biologically based, including a sexual division of labour, mental traits and desires.Footnote 16 In both of these phases, a variety of animal species (whether turtles, dogs or primates) served as competing models of naturalized human behaviour. In recent decades, this paper shows, scientists have mobilized the wide array sexual behaviours exhibited by animals to suggest instead that variation in human sexual behaviours, in turn, is not unnatural. The incorporation of numerous animal exemplars into Darwinian models of human sexuality opened a space between old polarities – of psychological fluidity and biological determinism – where naturalization need not require determinism.

Figure 1. ‘If homosexuality is inherited, shouldn't it have died out by now?’, George Booth, New Yorker, 16 August 1993, reprinted in Dean Hamer and Peter Copeland, Science of Desire, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994, p. 182. © George Booth/The New Yorker Collection/The Cartoon Bank.

Resisting psychosexual pathology

Evolutionary biologists are fascinated by sexual behaviour of plants and animals. They have linked reproduction to questions of progress or degeneration within populations (especially in eugenic theories of human development in the first half of the centuryFootnote 17), speciation and extinction (in the mid-twentieth centuryFootnote 18), and aggressive and cooperative behaviours (in subsequent decadesFootnote 19). As a result, attending to sexuality in evolutionary theory is not difficult. Reproduction is what makes evolution by both natural and sexual selection work – one individual survives, reproduces and passes their genetic material on to the next generation. This fascination characterizes students of animal behaviour equally well, perhaps in part because mating displays provide occasions to observe highly visible (and sometimes spectacular) species-specific courtship behaviours. Biologists themselves know this. Helen Spurway and J.B.S. Haldane wrote in 1953, ‘Animal ethology is mainly the study of complex coordinated muscular movements culminating in consummatory acts useful for the preservation of the species. Among these processes are breathing, drinking, eating, and reproduction, often in that order of priority.’ However, they added, ‘Ethologists have studied them in the opposite order of priority.’Footnote 20 As should be clear, however, non-procreative sexual activity mattered far less.

Within this substantial literature, the publications that refer to homosexuality in passing greatly outnumber those that took the theme as the focus of their investigations. Before the Second World War, scientists often used ‘inverted’ behaviour in animals (almost always males) as a diagnostic tool to measure the ‘naturalness’ of experimental set-ups. When comparative psychologist Gladwyn Kingsley Noble observed in the 1930s that in captivity male spotted turtles attempted to mount other males, for example, he became fascinated by documenting the behavior of the ‘ridden male’. When he observed turtles in their ‘natural habitat’ – and found no evidence of similar behaviour – he dismissed all of his laboratory observations as ‘valueless’ and filled the living quarters of the turtles in his laboratory with leaf litter to restore ‘natural’ courtship.Footnote 21 For experimental psychologist John B. Calhoun, his overcrowded rat cities proved a similar lesson in the 1950s and 1960s: urbanization and increased population density led causally to deviant social behaviour, including same-sex mounting behaviour, and also violence, cannibalism, social withdrawal and a loss of the maternal instinct in females.Footnote 22 In this context, purported homosexuality in animals reflected unnatural living conditions; it was a symptom rather than a behaviour to be studied in its own right.

Not until evolutionary biologists began to recognize same-sex sexual behaviours in animals as natural – that is to say, as occurring in wild populations and not just in potentially confounding laboratory settings – did they consider homosexual behaviour a biological trait whose evolution begged explanation. This took time, data, countless observations of animal courtship and a shift in perception. Trained as a zoologist, Alfred Kinsey argued that all sexual behaviour that humans engaged in counted as ‘normal’ through its very existence.Footnote 23 Many of the researchers at the Indiana University's Institute for Sex Research (more popularly known as the Kinsey Institute) adopted this ethic, even when their disciplinary backgrounds varied considerably. People who engaged in homosexual behaviour, Kinsey wrote, ran into difficulty because judgements of abnormality were ‘primarily moral evaluations’ with ‘little if any biologic justification’. Rather than being a result of psychopathology, he continued, ‘the problem of the so-called sexual perversions … is a matter of adjustment between an individual and the society in which he lives’.Footnote 24 Ethicists, sociologists, anthropologists, biologists, psychologists and theologians, Kinsey suggested, would necessarily have differing judgements of what constituted ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ behaviour (sometimes rendered ‘natural’ and ‘unnatural’). In science, he held by way of contrast, questions of morality should never apply. Rather than dichotomizing humans into distinct categories of homo- and heterosexual individuals, Kinsey and his colleagues rated the range of sexual experiences from exclusively heterosexual (0 on a sliding scale) to exclusively homosexual (6), with gradations in between.

One of Kinsey's co-authors and a New York-based sex therapist, Wardell Pomeroy eagerly argued in the pages of Playboy that polygamy, masturbation, homosexuality, mouth–genital stimulation and face-to-face intercourse topped his list of behaviours exhibited by non-human animals. Even sexual relations with inanimate objects were more common than most people assumed. He continued, ‘the difference between humans and other mammals, therefore, is one of degree and not of kind’.Footnote 25 Pomeroy found a simple comparison of humans to other animals insufficient to define typical sexual behaviour, because rape, incest and sadism also occur in mammalian species. So he adopted a series of criteria by which readers might define so-called normal behaviour – statistical (which behaviours are common among humans?), phylogenetic (do animals do it?), moral (according to accepted social norms, should we engage in these behaviours?), legal (what does the current law prohibit?), and social (do such behaviours hurt other people?). Given the wide variety of things people meant by ‘normal’, Pomeroy argued that normality was a useless metric by which to judge sexual behaviours, and suggested that people should feel free to engage in all kinds of sexual activities, as long as their actions did not interfere with anyone else's liberty.

Another (less publicly visible) scientist who remarked on the widespread occurrence of homosexual behaviour in animals was Frank Beach.Footnote 26 Beach worked at the American Museum of Natural History under Noble, and after Noble's death took charge of the Laboratory of Animal Behaviour at the museum for a few years before decamping to Yale University. Beach had trained with animal psychologists Karl Lashley and Harvey Carr at the University of Chicago and came to New York fascinated by animal models of human behaviour and questions about sex, sexuality and their hormonal control. In many of the species he studied, Beach noticed that animals engaged in same-sex sexual behaviour and, like Kinsey, took this as a sign of the behaviours’ normalcy. A few years earlier, primatologist Solly Zuckerman had written that he had observed homosexual interactions in young and adult primates at a zoological garden, where both male–male and female–female mounting behaviour appeared to function as regular signals of social dominance.Footnote 27 The individual higher in social status always mounted the subordinate individual, Zuckerman suggested, and such encounters were far from uncommon. In the first English translation of André Gide's Corydon in 1950, Beach penned eleven brief pages of comments in which he was quite clear about the lesson to be learned from animal behaviour for humans. Gide had won the Nobel Prize in Literature three years earlier and considered Corydon an important, necessarily controversial defense of homosexuality.Footnote 28 Beach wrote, ‘People who say that homosexual activities are biologically abnormal and unnatural are wrong’, but also updated Gide's contentions about animal behaviour in light of recent research, including Zuckerman's.Footnote 29

One of the difficulties besetting contemporary discussions of homosexuality, Beach claimed, was the profusion of definitions. To his way of thinking, ‘Homosexuality refers exclusively to overt behaviour between two individuals of the same sex. The behaviour must be patently sexual, involving erotic arousal and, in most instances, at least, resulting in satisfaction of the sexual urge.’Footnote 30 Beach noted Gide's intimation in his second dialogue that males were more likely than females to engage in homosexual acts because their sexual drive far outpaced that of females. Beach disagreed. He noted that female animals and women were equally likely to exhibit same-sex attraction and behaviour as males and men. Beach also suggested that any biological understanding of homosexual behaviour would have to take account of the fact that ‘different degrees’ of behavioural ‘intergradation’ existed. Again following Kinsey, Beach argued that if one were to simplify the range of possible behaviours into three categories of identity – strictly heterosexual, strictly homosexual and bisexual – then the zoological evidence ‘might predict that bisexual human beings would outnumber the other two groups combined’.Footnote 31

Beach belonged to a group of American scientists who referred to themselves as ‘psychobiologists’ – a category that has largely disappeared from our current scientific vocabulary. Like Kinsey and Noble, much of his research on sex and hormones was funded by the National Research Council, Committee for Research in Problems of Sex.Footnote 32 As the name suggests, psychobiologists sought (and continue to seek) to understand the biological and psychological grounding of human behaviour in animal models and were fascinated by the sexual behaviour of their research organisms.Footnote 33 Psychobiologists often referred to same-sex encounters in animals as ‘homosexual’.Footnote 34 When he observed an individual animal engaging in sexual encounters with both males and females, Beach concluded that these individuals might possess a ‘bisexual neuromuscular organization’. (Or such individuals might just be exhibiting synchronized breeding cycles – when fish spawned in close proximity to many other individuals, for example, it was hard to tell the difference.Footnote 35) Combined, the research of psychobiologists recognized the widespread existence of same-sex sexual behaviours in the animals they studied. This opened up the possibility that comparative evidence from animals could contribute to ongoing arguments for the normalcy of same-sex desire and sexuality. This was true, at least in the case of Beach, who took on this perspective directly and in print.Footnote 36

Across the Atlantic, British zoologist Desmond Morris also found these questions fascinating. Drawing from his dissertation research on ‘pseudomale’ and ‘pseudofemale’ behaviour in stickleback fish and zebra finches – that is to say, males that exhibited female-typical courtship behaviours and vice versa – as well as the research of the psychobiologists, he remarked in 1952 that the species in which pseudofemale and pseudomale behaviour had been observed were exactly those species that had been studied extensively. He believed that this indicated ‘that such behaviour is of a much wider occurrence in the animal kingdom than was previously believed, and that it is only revealed after a detailed study of the animal concerned has been carried out’.Footnote 37 In 1955, Morris tried to clarify the relationship between sexual inversion on the one hand (meaning pseudomale and pseudofemale behaviour) and homosexuality on the other.Footnote 38 Self-consciously following Kinsey, Morris sought to make his behavioural terminology comparable to Kinsey's in discussing human behaviour – homosexual encounters, then, necessarily involved two individuals of the same sex, only one of whom behaved in a sex-inverted fashion. If a male acting like a female engaged in courtship with a female acting like a male, then biologists, he believed, should refer to that as a case of heterosexual courtship.

In his sensationally popular The Naked Ape, Morris further distinguished between a ‘homosexual act of pseudo-copulation’ and ‘the development of a homosexual fixation’.Footnote 39 The former, he noted, was far from ‘unusual … many species indulge in this, under a variety of circumstances’. But, he continued, ‘the formation of a homosexual pair-bond is reproductively unsound, since it cannot lead to the production of offspring and wastes potential breeding adults’. Many other human behaviours, of course, fell into the same category and a few pages later he pointed out that ‘[s]uch groups as monks, nuns, long-term spinsters and bachelors and permanent homosexuals are all, in a reproductive sense, aberrant. Society has bred them, but they have failed to return the compliment’.Footnote 40 He implied, through association with these other cultural identities, that exclusive homosexuality was, if not a lifestyle choice, then the result of social circumstances rather than biology, even though occasional sexual encounters between two males could be expected as a part of any individual's lifetime sexual repertoire – he was silent on sex between females.Footnote 41

By the end of the 1960s, public assumptions about sex and sexuality were rapidly changing.Footnote 42 Playboy magazine gained steadily in distribution, becoming a dorm room staple if not entirely respectable. With help from contraception in the form of a discrete pill, the sexual revolution was blooming.Footnote 43 Books on the sexual behaviour of Americans continued to generate sales and controversies, from William Masters and Virginia Johnson's Human Sexual Response to Alex Comfort's The Joy of Sex (which spent over a year on the New York Times bestseller list).Footnote 44 Morris's Naked Ape built on recent research in sexology to argue that humans’ capacity for sexual pleasure helped unite men and women in cooperative long-term sexual unions that, in turn, formed the basis of human social structures.Footnote 45 In the midst of this sexual revolution and building on a decade of media attention to questions of homosexuality raised in part by the controversy over the Kinsey reports, the underground circulation of gay and lesbian magazines, guides and gossip sheets helped forge an increasingly visible gay community.Footnote 46

Even among heterosexuals, countercultural stereotypes seemed to push against the previous generation's clear division between feminine and masculine forms of dress and behaviour. In June 1962, for example, a Playboy panel on the ‘Womanization of America’ asked eight men to reflect on the newfound ‘dominance’ of women in society and whether these new women posed a threat to traditional manhood.Footnote 47 Most of the scientists were psychologically trained, with the exception of one anthropologist, Ashley Montagu – author of The Natural Superiority of Women.Footnote 48 The panel concluded on a hopeful note, that ‘a new spirit on the land’ would teach American youth that ‘one can be masculine without being hairy-chested and muscular; the women, that one can be intelligent and sensitive – and witty and wise – and at the same time completely feminine’. In these new roles for boys and girls the panelists saw a greater range of gender roles, ‘an acting out at last’ that could breathe fresh air into American society.Footnote 49 (Future Playboy issues, however, reinforced precisely the ‘hairy-chested and muscular’ masculinity that the panel had scorned as too limiting.)

A more radical gay liberation movement followed – building on the successes of the homophile movements of earlier decades – in which activists successfully fought for the decriminalization of homosexual acts and an end to police harassment and other visible signs of cultural oppression. A sign of their success came in 1973 when the American Psychiatric Association (APA) removed homosexuality from the highly influential Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. In the debates within the APA around the (de)classification of homosexuality, Beach's animal experiments formed an important basis of argumentation.Footnote 50 Over the course of the twentieth century, American psychiatrists had concentrated more intensely on ‘abnormal’ behaviour rather than ‘normal’, as homosexuality itself had been increasingly normalized in cultural and scientific perceptions. The depathologizing of homosexuality in psychiatry reflected the synergy of these trends and a disaggregating of homosexuality from associations with disability and mental illness. With respect to gender variance and ‘transsexuality’, these associations would remain in force, in part because ‘pathology’ had the pragmatic benefit of providing access to treatment in the form of gender-affirming therapies and surgeries. The disaggregation of ‘homosexuality’ from ‘transsexuality’ and gender variance took place both within psychiatry and also among homophile and later gay rights activists, avouching gender and sexuality as distinct categories of human experience.Footnote 51 By the mid-1970s, environmentalist explanations of homosexuality as a pathological reaction to overcrowding in cities were also disappearing.Footnote 52 The depathologizing of homosexuality, however, renewed it as a subject of biological fascination – as an evolutionary conundrum.Footnote 53 The scientific discipline through which questions of homosexuality's normalcy would be negotiated in coming decades thus shifted from medicine to biology. At first, this took the form of fitting homosexuality into blossoming debates over determinism in evolutionary theories of human behaviour.

Modelling heterosexuality

This shift to biology as the proving ground of natural sexuality introduced new vocabularies with which scientists located the behaviours they investigated. In the mid-1960s, professional terminology was still very much in flux, reflecting contemporary social flexibility in defining sexual orientation. Natural and social scientists in turn sought to distinguish between ‘homosexual’ and ‘homosocial’ spaces and behaviours.Footnote 54 Beach, for example, had used ‘homosexual’ to mean a single-sex group of individuals, regardless of their sexual predilections or practices. Morris, in The Naked Ape, instead referred to single-sex non-sexual groups as ‘unisexual’, to help distinguish them from ‘homosexual’, and noted that ‘the important role they play in the lives of adult males reveals the persistence of the basic, ancestral urges’.Footnote 55 When the terminological dust settled, ‘homosexual’ implied an individual's preference for sexual encounters with members of the same sex, while ‘homosocial’ referred to single-sex social environments without any necessary reference to sexual activity, like an all-male boarding school. This generation of evolutionary theorists of human behaviour defended all-male homosocial groups as fundamental to the origins of human sociality and intelligence, but in doing so reproblematized exclusive homosexuality as a logical riddle in need of a solution.

As mid-career social scientists entranced by questions of evolution and human behaviour, social anthropologists Robin Fox and Lionel Tiger concurred with Morris's conclusions, if not with his terminology. In their first of many collaborative publications, Fox and Tiger sought to imbue the social sciences with a zoological perspective – a move they believed would bring intellectual rigour to the field.Footnote 56 Social scientists should pay more attention to recent theories in the biological sciences, they argued, especially insights gleaned from the study of animal behaviour as an evolutionary subject. Of particular interest to Fox were questions of kinship, especially the mother–child bond as the primary basis for determining kinship patterns in both humans and non-human primates.Footnote 57 Tiger, for his part, was gripped by how males related to other males in human groups.Footnote 58 Both found inspiration in research by primatologists like Michael Chance, who first became interested in the natural behaviour of his animal subjects as a means of diagnosing humane laboratory conditions (much like Gladwyn Kingsley Noble). By the 1960s, Chance had started to argue that aggression rather than sexual relations primarily structured social relations in animals and people, and it was this research that grabbed the attention of Fox and Tiger.Footnote 59 Humans’ evolutionary heritage constrained our actions, they argued, shaping the social behaviour studied by sociologists and anthropologists.Footnote 60 Fox and Tiger wanted humans to remain the focus of the social sciences but hoped that their analyses would become more nuanced as a result of this biological lens. When we look at their research as a whole, a sexual division of labour becomes clear: competitive heterosexual men hunted and preferentially socialized in small, homosocial groups whose structure dictated the social organization of the entire community; women reproduced and occupied a heterogeneous domestic world filled with other women, children of both sexes and men returned from the hunt.Footnote 61

Fox and Tiger defensively positioned themselves and the naturalness of homosocial association between adult men against both feminists and Freudians (their labels), basing their research on an ostensibly universal grammar of behaviour in primates and humans.Footnote 62 Challenges to their conclusions appeared almost immediately, many indeed penned by women.Footnote 63 Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, women entered graduate school in greater numbers to start professional scientific careers.Footnote 64 From the perspective of Tiger and Fox, feminists were fighting against both social tradition and their own evolutionary heritage. For their critics, such supposedly universal biological constraints on human behaviour functioned to exclude women from professional spaces, safeguarding them as a masculine preserve. At issue were biological meanings of all-male associations: were all-male groups socially discriminatory and perhaps subversively sexualized, or were they ‘natural’ and therefore to be explained through evolution?

The reinscription of gendered norms of sexual behaviour was taken up by researchers in animal behaviour (independent of whether they had been trained in biology or anthropology departments). Recall that psychobiologists had known about same-sex sexual behaviour in animalsFootnote 65 – as had at least some members of the non-science-reading public – and used their research to argue that homosexuality was biologically normal in Pomeroy's statistical and phylogenetic meanings of the word. Even Konrad Lorenz in his broadly read On Aggression had recorded examples of what he called ‘triangular marriages’ in graylag geese, between two males and a female. These sexually bonded groups, he related, were a considerable biological success and usually topped the social hierarchy of the colony. He concluded that when two male geese successfully courted each other, exhibiting a ‘“homosexual” triumph bond’, this could not be regarded as ‘pathological … since it also occurs in wild geese in the natural state’.Footnote 66 Evolutionary explanations of homosexuality as a biological trait were relatively new. Not until after biologists accepted homosexuality as non-pathological did they seek to incorporate it into their primary theoretical framework for discussing the evolution of human behaviour. As soon as biologists did, however, they began to wonder how homosexuality could have originated, and once present be maintained, if only human behaviours that maximized individual reproduction were favoured by natural selection.

As early as 1959, ecologist G. Evelyn Hutchinson had speculated about the evolution of non-reproductive sexual behaviours and included fetishisms along with homosexuality as behaviours likely to decrease the rate at which individuals reproduced. Hutchinson suggested that heterozygote selection might provide a solution.Footnote 67 He argued that like sickle-cell anaemia, fetishisms might exist because people heterozygous for the gene that coded for the trait (that is, they were ‘carriers’ of the trait but did not suffer from sickle-cell anaemia themselves) survived and reproduced at a greater rate than those who were not carriers. In the case of sickle-cell, heterozygotes were protected against malaria.Footnote 68 For this argument to work, Hutchinson assumed a one-gene model for homosexuality. A decade and a half later, however, evolutionary arguments usually meant interpreting homosexual behaviour itself as an adaptation, as a trait that conferred a reproductive advantage on individuals who exhibited it.Footnote 69

Critics of evolutionary approaches to human nature in the 1970s crafted a new term – biological determinism – that enabled them to counter arguments for a biological basis of a wide variety of human traits, whether those were innate differences between the sexes, purported links between race and IQ, or sexual orientation.Footnote 70 To understand these politics, we must turn to the professional fallout from E.O. Wilson's publication of Sociobiology: The New Synthesis in 1975.Footnote 71 Two interrelated claims proved to be major sticking points among sociobiology's critics: that homosexual behaviours could be explained through heterosexuality and that, because homosexual encounters had been documented more frequently in male animals than in females, this demonstrated more generally that men had higher sexual drives than women.

Wilson had considered exclusive homosexuality to be an evolutionary puzzle to which evolutionary reasoning held the key. Early in Sociobiology, Wilson suggested that behaviours that might at first glance appear to be abnormal could prove to be adaptive upon closer inspection – including homosexuality. Biologists, he noted, had documented ‘pseudo-copulation’ in macaques, as a ritual expressing rank among males, and in South American leaf fish, where some males mimic the colouration of the females in order to slip past the notice of territorial males. He wondered, did the latter case represent ‘a case of transvestism evolved to serve heterosexuality?’Footnote 72 In addition, British mathematical theorist George C. Williams remarked in his Sex and Evolution (also published in 1975) that homosexual behaviours in male animals provided evidence of the hyper-variability of male sexuality in comparison to female sexuality, drawing on long traditions of assuming that males exhibit greater variability than females in any number of traits.Footnote 73

More specifically, Wilson argued that ‘the homosexual state itself’, by which he meant that ten percent of the male population who scored a 6 on Kinsey's scale, should result in ‘inferior genetic fitness’ because these men would have fewer children than the remaining 90 per cent of American males.Footnote 74 Citing the research of geneticist Franz Kallmann, Wilson further suggested ‘the probable existence of a genetic predisposition toward the condition’. Kallmann himself had been more circumspect, concluding merely that the accumulated research ‘throws considerable doubt upon the validity of purely psychodynamic theories of predominantly or exclusively homosexual behaviour patterns in adulthood’.Footnote 75 How, then, Wilson asked, did homosexuality persist in human populations – not just in the US but also around the globe? He advanced a series of hypotheses.Footnote 76 Following Hutchinson's logic, he suggested there might be a yet-to-be-discovered heterozygous advantage. He found a different possibility more convincing, however: that ‘homosexual members of primitive societies may have functioned as helpers, either while hunting in company with other men or in more domestic occupations at the dwelling sites’. Through kin selection alone, he reasoned, homosexual preferences might spread in a population. ‘Freed from the special obligations of parental duties, they could have operated with special efficiency in assisting close relatives.’ (We can see in these theories an inarticulate endorsement of the venerable inversion hypothesis, where male homosexuality was associated with greater domesticity.) Wilson also left room for the action of the environment, suggesting that once genes controlling the expression of homosexuality were found, he suspected they would exhibit incomplete penetrance and be variable in expression.

Sociobiologists’ two favoured theories for explaining the evolution of all sexual behaviour in humans were sexual selection – reproductive behaviours shaped by female choice of mates and male–male competition over territory and females – and kin selection to account for non-reproductive behaviours. In Wilson's words, the possibility of explaining the evolution of homosexuality in terms of kin selection ‘should give us pause before labelling homosexuality an illness’.Footnote 77 Like William D. Hamilton's account of the evolution of altruism (another apparent conundrum, where individuals sacrifice their own potential reproduction for the survival and continued health of their relatives), Wilson reasoned that selection could favour homosexuality through advantage conferred on relatives – the cumulative reproductive success of nieces and nephews, each of whom carried (on average) a quarter of the genetic material of their parents’ siblings, provided the evolutionary fitness of the otherwise childless ultra-uncle.Footnote 78 (That the theory became known as the ‘avuncular hypothesis’ draws our attention to the continuing silence of evolutionary theorists regarding benevolent aunts.Footnote 79) This line of thinking effectively reinforced homosexuality as an individual identity, rather than a set of behaviours, dichotomously setting apart ‘homosexuals’ from ‘heterosexuals’.

Critics of sociobiology like geneticist Richard Lewontin argued vehemently that this reductionist thinking constituted a caricature of Darwinism and could never count as politically progressive.Footnote 80 I quote a piece of his argument at length to illustrate both his anger and dismissal of Wilson's logic:

First, it is supposed, on no evidence, that homosexuality is genetically based, despite the known immense variation in the frequency of homosexual and heterosexual behaviour in history and between social classes. Second it is assumed with no evidence that homosexuals leave far fewer offspring than heterosexuals. But this is a typological view of sexual behaviour. Obviously, persons who engage only in homosexual behaviour can have no offspring. But there is an immense range between complete homosexuality and complete heterosexuality. Do persons who engage in homosexual encounters, say, 14 per cent of the time, leave fewer offspring? Perhaps they have higher libido and leave more. What is the evidence? Finally we have the totally untestable story, with no ethnographic evidence, that in ‘primitive societies’ homosexuals used to be helpers. While the construction of such stories is an amusing pastime, it cannot be taken seriously as science.Footnote 81

Lewontin ended his attack succinctly, ‘The naive reductionist program of sociobiology has long been understood to be a fundamental philosophical error. Meaning cannot be found in the movement of molecules.’Footnote 82 These arguments formed the basis of his involvement in the Sociobiology Study Group, a Boston-based organization with overlapping membership in Science for the People and the New York-based Genes and Gender group.Footnote 83 Lewontin's criticisms of sociobiology found their culmination in his co-authored Not in Our Genes: Biology, Ideology, and Human Nature, when once again homosexuality constituted a key example demonstrating sociobiologists’ fallacious reasoning.Footnote 84 The authors again emphasized the lack of evidence for any of Wilson's hypotheses – no information existed on the reproductive rates of men who had sex with other men, much less the reproductive rates of men who identified as bisexual; on the genetic basis of homosexuality; or on whether homosexuals act to increase the reproductive rates of their relatives.Footnote 85 In the face of such criticisms, Wilson and his defenders remained unmoved.Footnote 86

The ideological polarization of arguments for the genetic, evolutionary basis of human behaviour helps account for the politics of evolutionary ideas about homosexuality in the late 1970s and early 1980s: claims that human behaviours were constrained by biological circumstance were considered socially conservative, while arguments in favour of environmentalist explanations of behaviour coded as politically left.Footnote 87 Sociobiologists proposed a number of other possibilities as well: the much older idea that homosexuals might be created as a result of genetics and social circumstances at home, this time due to a phenomenon they called ‘parental manipulation’, and a theory that homosexuality might be a by-product of selection for some other trait.Footnote 88 Evidence favouring any one of these suggestions over another was in short supply, which just fuelled the possibilities.Footnote 89

One of the most remarkable corollaries of sociobiologists’ logic came from Donald Symons's Evolution of Sexuality, published in 1979.Footnote 90 In Symons's vision, homosexual behaviour became the best yardstick by which to measure normative heterosexual behaviour. If, as Wilson and others had argued, male and female heterosexual reproductive strategies fundamentally differed, then every sexual encounter between a man and a woman represented a compromise between their duelling desires and agendas. How best, then, to understand true male behavioural patterns? In sexual encounters unfettered by female reluctance. Symons wrote,

Heterosexual men would be as likely as homosexual men to have sex most often with strangers, to participate in anonymous orgies in public baths, and to stop off in public restrooms for five minutes of fellatio on the way home from work if women were interested in these activities. But women are not interested.Footnote 91

He concluded that ‘available data on the sex lives of contemporary homosexuals may have far-reaching implications for understanding human sexuality. These data imply that male sexuality and female sexuality differ much more profoundly than might be inferred from observing only the heterosexual world’.Footnote 92 Symons's account reinforced gendered stereotypes already inscribed in evolutionary theory – that men's sexual drives led them to have profligate sexual interests, although they were, of course, most attracted to the young, fertile women who would allow them to produce the largest number of offspring, and that women were much less interested in sex, preferring stable relationships with older, established male mates in order to protect a smaller number of offspring.Footnote 93 Symons argued that the frequency of sex among male homosexuals illustrated that males possessed a greater sex drive than females, derived from the far greater evolutionary importance of male sexual pleasure. In fact, he hypothesized that ‘the human female's capacity for orgasm is no more an adaptation than is the ability to read’.Footnote 94

Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, a feminist sociobiologist, found Symons's characterization of female sexuality ‘both more original and more controversial’ than his descriptions of male sexual behaviour, countering with her own observations in primates of homosexual encounters between two females and female mounting behaviour as evidence of females’ sexual nature.Footnote 95 In The Woman That Never Evolved, she sought to break down assumptions like Symons's that males were sexually motivated (and variable) and females were not.Footnote 96 In addition, Hrdy sought to revise evolutionary explanations of parenting. Using evidence from comparative anthropology and primatology, she convincingly argued that most offspring, whether non-human primates or human children, are raised by a fluid collection of (semi-)responsible adults. Sometimes that might involve one male and one female, both of whom served as the genetic parents of the child, but usually non-direct relatives contribute as well. In this sense, Hrdy did not need a special explanation for non-reproductive parenting behaviour because she assumed that offspring care often involves non-biological parents. Even Hrdy, so intent on revising sociobiologists’ theories of sexuality in females, argued for the existence of ‘homosexual behaviour in the natural world, both male–male and female–female’, but added, ‘What we have yet to document is a lifetime strategy of homosexual behaviour.’Footnote 97 In the preface to the revised version of The Woman That Never Evolved, she suggested that Symons's book provided the ‘founding document’ for the new field of evolutionary psychology based on the version of Darwinian sexual selection theory she sought to dismantle as inappropriately relying on ‘ardent’ males and ‘coy’ females.Footnote 98 Not surprisingly, she noted, in the years between the two versions of the book, Symons became an outspoken critic of her ideas.Footnote 99

Dean Hamer read these evolutionary theories with interest and disappointment. In the body of The Science of Desire, he wrote that two books had inspired him to change fields and begin looking for a genetic basis of homosexuality: Darwin's Descent of Man, which he found while browsing through a bookstore in Oxford, and Not in Our Genes by ‘Lewontin and colleagues’.Footnote 100 The first he adored, especially Darwin's long passages on the evolution of sexual behaviour and the implication that sexuality ‘has a significant genetic component’. (For historians, the anachronism is striking; there was no concept of the gene in 1871.) The second he hated, deeming Lewontin's analysis political rather than scientific. Why, Hamer wondered, had Darwin been so convinced that human behaviour was at least partially inherited, years before the scientific community had worked out the basics of the field that would be known as genetics, and Lewontin, although trained in genetics a century later, found this very same idea antithetical? He decided there was ‘room for some real science here’.Footnote 101

Then in 1991 Simon LeVay published an article in the pages of Science announcing that a region in the anterior hypothalamus was more than three times smaller in brains of homosexual men (and women with unknown sexual orientations) than in heterosexual men.Footnote 102 LeVay concluded that the variation of the INAH-3 region (or third interstitial nucleus of the anterior hypothalamus) with sexual orientation suggested a ‘biological substrate’ to sexuality. Hamer's research appeared in Science, too, a couple of years later.Footnote 103 He posited that a region on the tip of the long arm of the X chromosome (Xq28) likely contained genes linked to sexual orientation, although he could not yet identify which genes might be located there or their physiological effects. Their work was suggestive but both men admitted they needed more data to demonstrate a conclusive biological basis for male homosexuality – and scientific evaluations of their research agreed.Footnote 104 The general public missed the nuance of these qualifications, however, in part thanks to contemporaneous excitement over the Human Genome Project and the promise of genetic research as a tool for understanding a wide array of human behaviours and identities.Footnote 105

In the early 1990s, ‘born this way’ activists in the United States had found new biological voice by engaging with Hamer's quest to find a genetic basis for homosexuality, LeVay's attempts to locate a neurological region of the human brain responsible for homosexuality, and new twin studies by J. Michael Bailey and Richard Pillard. The last of these suggested that brothers of gay men were more likely to also be gay if they were identical twins rather than fraternal twins or (biological or adoptive) brothers.Footnote 106 None of these men drew significantly on comparative evolutionary frameworks by citing the vast array of reproductive modes in animals. Media coverage forged links between these independent research projects, and Hamer and LeVay capitalized on this interest, co-publishing an article in Scientific American timed with the release of their books aimed at non-specialist readers.Footnote 107 Hamer and LeVay's genetic and neurobiological experiments, respectively, provided ready evidence that homosexuality was not a ‘choice’ but possessed a biological basis. Their research grabbed public attention at a moment when the nation was wrestling with more than 250,000 documented deaths due to AIDS-related health complications, without antiretrovirals to treat HIV infection, and deeply concerned with the spread of the disease from gay men and IV-drug users to the ‘normal’ public, including haemophiliacs and recipients of blood transfusions.Footnote 108 For groups like ACT UP, the gross neglect of the federal government in the face of a deadly pandemic disproportionately affecting gay men was far more important than advocating for a biological basis of homosexuality.Footnote 109 Within the history of the life sciences, genetics, neurobiology, and studies of animal behaviour competed for explanatory power in accounting for human behaviour.Footnote 110

These scientists were hailed as heroes by some members of the LGBT movement; in their research lay proof that being gay was legal precedent for arguing that homosexuals were due protection under the law as a group of people defined by immutable identity, a long step beyond decriminalization.Footnote 111 The benefits of this legal line of argumentation were less clear to others.Footnote 112 If a biological basis for homosexuality were to be convincingly demonstrated, this could be a step towards attempts to selectively breed it out of existence or find a ‘cure’.Footnote 113 Hamer, for example, was already defending against this possible interpretation in his original Science paper: ‘We believe it would be fundamentally unethical to use such information to try and assess or alter a person's current or future sexual orientation’. The paper concluded, ‘Rather, scientists, educators, policy-makers, and the public should work together to ensure that such research is used to benefit all members of society.’Footnote 114 These new studies also seemed to support the idea that men were bimodally either straight or gay, and therefore that Kinsey's model of a sliding scale of sexual orientation had been incorrect.Footnote 115 In this light, the persistence of evolutionary accounts of homosexuality traced a fine line between essentializing homosexuality as a biological identity in need of explanation and offering animal models as a possible source of biological liberation.Footnote 116

By the early 1990s, legal activists were seeking to overturn state sodomy laws as violations of privacy and also to define homosexuality as a ‘suspect classification’.Footnote 117 That the group in question had been subject to long-standing persecution was beyond doubt; the key was providing evidence that the trait defining the group was ‘immutable’.Footnote 118 Biological reasoning thus proved to be as useful to breaking down this legal apparatus as medical logics had been in erecting it.Footnote 119 Around the same time, the sexual habits of animals began to play a role in public discussions about the biological basis of homosexuality, at first through observations of laboratory or zoo animals as one-to-one guides for modelling human sexuality, and by the end of the century with an eye towards animal behaviour in the wild.Footnote 120

Binders full of animals

What, then, is the role of biologically based arguments in defence of human rights? Is the investment of evolutionary attention to questions of sexuality a ‘good’ thing for gay rights? Or are there hidden dangers in the persuasive power of naturalistic reasoning when it comes to sexuality? Some professional biologists in the mid-twentieth century argued that homosexuality had a biological basis and therefore an evolutionary ontology. One tempting explanation for why these ideas were not more widely mobilized politically is that a common means of critiquing evolutionary arguments of human behaviour was to suggest that they presupposed a genetic basis without any evidence. Perhaps better, then, to argue for a ‘gay gene’ or ‘gay brain’ and assert the plausibility of subsequent evolutionary explanations. In this vein, scientists like Hamer, LeVay, Bailey and Pillard remained fairly agnostic as to which evolutionary explanation would prove the most robust.Footnote 121 When evolutionary biologists in the last quarter of the twentieth century engaged with questions of homosexuality their own explanations reinforced their understanding of normative heterosexuality – gay men exemplified hyper-masculine heterosexual norms because they never had to compromise in their sexual proclivities. This put naturalistic arguments for LGBT rights in awkward juxtaposition with arguments against the naturalization of gender, but this need not have been the case.Footnote 122

In recent decades field biologists have documented hundreds and hundreds of examples of species who exhibit same-sex courtship behaviour, sex-changing behaviours, hermaphroditism, and more. Bruce Bagemihl's Biological Exuberance, published in 1999, provided an exhaustive accounting of this ‘polysexual, polygendered world’. Rather than working from one particular animal model to humans (in a case study approach), Bagemihl instead suggested that readers should recognize that the breadth of sexual behaviours and patterns found in animals could serve as a guide for thinking about the diversity of sexualities exhibited by humans.Footnote 123 Joan Roughgarden entered the fray with Evolution's Rainbow, in which she sought to undermine sexual selection theory by similarly mapping the non-binary, non-normative sexualities and genders of the planet's flora and fauna.Footnote 124 Bagemihl, Roughgarden and others defined nature as containing a plethora of sexualities, genders and kinship structures.Footnote 125

The reading public finds biological arguments documenting the occurrence of same-sex relations in animals incredibly persuasive, reflecting an endless appetite for normative explanations of human behaviour but also providing a powerful political tool.Footnote 126 This has been amply demonstrated with the success of legislative arguments for gay marriage in American courts.Footnote 127 Scientific knowledge evolves, too, of course. Historical explorations of the persistence of the naturalistic fallacy – the slide between ‘is’ and ‘ought’ when it comes to the order of nature – teach us that progressive biological arguments can be upended with time.Footnote 128 In 1991, biologists John Kirsch and James Weinrich expressed this concern, noting, ‘There are plenty of morally wrong things that are perfectly natural in the evolutionary sense.’ They continued, ‘our aim … has not been to justify homosexual behaviour on biological grounds, but rather to show that the frequent condemnation of gay people because homosexual behaviour is unnatural must be rejected because the premise of unnaturalness is false’.Footnote 129 If concerns over the naturalistic fallacy make us wary of using a specific animal model as a guide to human sexuality, that should not dissuade us from the persuasive power of behavioural research to disprove claims of unnaturalness.Footnote 130

In 2003, the American Psychological Association submitted an amicus curiae brief to the US Supreme Court in the case of Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003), in support of overturning the Texas Penal Code, which prohibited consensual sexual activity between persons of the same sex. The APA suggested, ‘Heterosexual and homosexual behaviour are both normal aspects of human activity. Both have been documented in many different human cultures and historical eras, and in a wide variety of animal species.’ They cited a recent compilation of sexual behaviour in animals, Bagemihl's Biological Exuberance, and Clellan Ford and Frank Beach's much older Patterns of Sexual Behaviour, published in 1951.Footnote 131 In a surprising twist, given the excitement over genetics in the 1990s, the APA also noted,

Although much research has examined the possible genetic, hormonal, developmental, social, and cultural influences on sexual orientation, no findings have emerged that permit scientists to conclude that sexual orientation is determined by any particular factor or factors. The evaluation of amici is that, although some of this research may be promising in facilitating greater understanding of the development of sexual orientation, it does not permit a conclusion based in sound science at the present time as to the cause or causes of sexual orientation, whether homosexual, bisexual, or heterosexual.Footnote 132

Although they sidestepped the issue of biological causation, the APA's amicus curiae brief supported the concept of immutability and pointed to Kinsey's studies of sexual behaviour in American men and women, as well as more recent work arguing ‘that most gay men and most or many lesbians experience either no choice or very little choice in their sexual attraction to members of their own sex’.Footnote 133 In the diversity of sexual behaviours exhibited by both animals and humans lay persuasive evidence supporting the designation of homosexuality as one of several immutable sexual identities, independent of biological proof of homosexuality's origins. Animal exemplars again took their place alongside data gathered about human sexual practices as science mobilized in defence of gay rights, this time creating the opportunity for naturalization without recourse to biological determinism.

Acknowledgements

I have presented this work to a number of welcoming and helpful communities: Boston University's Colloquium on Diversity, Plasticity, and the Science of Sexuality, especially Alisa Bokulich; the DC History and Philosophy of Biology reading group, with particular thanks to Lindley Darden and Eric Saidel; Stockholm University's Department of Ethnology, History of Religions, and Gender Studies, especially Malin Ah King; Karin Nickelson's Historisches Oberseminar, Perspektiven der Wissenschaftsgeschichte, LMU, with additional thanks to Christian Joas and Fabian Kraemer; the graduate seminar for visiting STS speakers at Cornell, with thanks to Suman Seth; and the entire Descent of Darwin crew. I gratefully acknowledge Don Opitz, Luis Campos, Angela Creager, Michael Gordin and the anonymous referees of this paper, all of whom were extraordinarily generous with their time and expertise – this paper is much improved for their efforts and I am sincerely grateful. Simon Werrett and Trish Hatton shepherded this volume through review and publication; without them, it would not exist. Finally, collaborating with Suman on Descent of Darwin these last years has been a true delight – I thank him for both his sharp analysis and boundless generosity.