Introduction

Identification of natural groups and assigning appropriate taxonomic ranks are among the main goals in systematics, and have become a key issue in conservation biology (Kelt and Brown Reference Kelt and Brown2000, Fraser and Bernatchez Reference Fraser and Bernatchez2001). Different viewpoints on species limits lead to different priorities for conservation assessments; hence, species concepts are of great importance in conservation (Hazevoet Reference Hazevoet1996, Peterson and Navarro Reference Peterson and Navarro1999, Peterson Reference Peterson2006), particularly when they extend to public and governmental agendas in which biodiversity protection is legislated. However, generating endangered species lists relies on a range of taxonomic surveys that sometimes lack a general agreement among scientists, thus making it difficult to assess conservation tags (i.e. units or areas) among regions and countries, especially if definitions of a species vary from place to place and from taxon to taxon (Goldstein et al. Reference Goldstein, DeSalle, Amato and Vogler2000). Also, the taxonomic validity of subspecies has been debated for more than 40 years, a debate that can affect conservation decisions (Ryder Reference Ryder1986, Ball and Avise Reference Ball and Avise1992, Wilcove et al. Reference Wilcove, McMillan and Winston1993, Barrowclough and Flesness Reference Barrowclough, Flesness, Kleiman, Allen and Harris1996, Cracraft Reference Cracraft, Claridge, Dawah and Wilson1997, Zink Reference Zink2004). Despite different points of view on the validity of subspecies, they have been considered as conservation units by several international conventions and organizations such as CITES (Inskipp and Gillett Reference Inskipp and Gillett2005) and IUCN (IUCN 2009), as well as in official endangered species lists of countries such as Brazil (MMA 2003), Australia (EPBCA 1999), Mexico (DOF 2002), United States (ESA 1973), Canada (SRA 2003), and Spain (Catálogo Nacional de Especies Amenazadas 2002). Hence, it is desirable to try to arrive at consistent nomenclatural units on which to establish conservation strategies.

Mexico holds approximately 1,060 biological species of birds, ~28% of which are listed under some national risk status. The NOM-059-ECOL-2001 (DOF 2002; hereafter ”NOM”) is the official list of threatened and endangered taxa protected by Mexican legislation, and is also the framework for conservation policies, commercial ventures involving biodiversity, environmental impact studies, hunting regulations, ecotourism development, and scientific collecting permits. Taxa are listed in the NOM based on several attributes: population size, distributional area, human impacts, and population trends. Taxa are placed in one of four NOM risk categories: extinct, endangered, threatened, or subject to special protection, the latter referring to taxa with insufficient information regarding their risk of extinction. Taxa included in the NOM can be either species or subspecies. These taxonomic units are based on the currently recognized taxonomic authority for each taxon. For birds, the authority list is that of Friedmann et al. (Reference Friedmann, Griscom and Moore1950), Miller et al. (Reference Miller, Friedmann, Griscom and Moore1957) and AOU (1998; and recent addenda, http://www.aou.org), all based on the traditional Biological Species Concept (BSC; Mayr Reference Mayr1942).

An alternative species-level taxonomy was recently proposed for Mexican bird species by Navarro-Sigüenza and Peterson (Reference Navarro-Sigüenza and Peterson2004; hereafter N&P), who outlined a taxonomy under the Phylogenetic Species Concept (PSC) and Evolutionary Species Concept (ESC) (Navarro-Sigüenza and Peterson Reference Navarro-Sigüenza and Peterson2004). Their taxonomy was based largely on evidence from morphology, genetic data, and vocalizations when available (see literature cited by N&P). Thus 135 biological species became 323 species, 122 of which represent “new” endemic forms for Mexico, and another 29 forms suggested as additional candidates for splitting. Although such a rise in the number of species may seem huge, it falls within the expected rate of 1.9 phylogenetic species per biological species detected by Zink (Reference Zink2004). This list of phylogenetic species, contrasted with biological species, provides the basis for the results reported here.

Because the diverse concepts for conservation units have been analyzed in detail in the literature (Riddle and Hafner Reference Riddle and Hafner1999, Kelt and Brown Reference Kelt and Brown2000, Fraser and Bernatchez Reference Fraser and Bernatchez2001), our goal focuses on analyzing whether species and taxa defined by N&P would provide a different approach for constructing endangered species lists and different prioritisation schemes, in contrast with schemes based on BSC and subspecies by using the Mexican avifauna as an example.

Methods

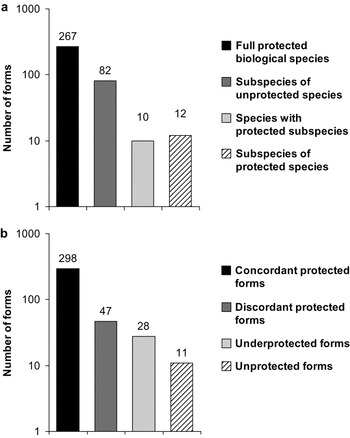

We compared the list of species and subspecies listed on the NOM with that of N&P (Fig. 1, Appendix 1 in Supplementary materials). Protected species usually contained multiple subspecies under different risk categories, so each component form was evaluated independently of its taxonomic category (e.g., Least Tern Sternula antillarum is subject to special protection, but S. a. browni is catalogued as endangered).

Figure 1. Number of current NOM protected avian species and subspecies (a), and changes in the NOM removing the subspecific category and considering the use of phylogenetic species proposed by Navarro and Peterson (2004) (b). In (b), the number of forms (373 considering only the concordant, the underprotected and the unprotected forms) does not coincide with those protected by the NOM (371) due to the existence of two indirectly protected forms but unrecognized by the NOM (see Appendix 1 in Supplementary materials). Y axes are log-transformed for better visualization.

We identified four management categories that encompass the analysis of putative taxa under risk: (1) Concordant protected forms: BSC species and subspecies listed in the NOM that correspond to phylogenetic species recognized by N&P. (2) Discordant protected forms: BSC species and subspecies that do not correspond to a phylogenetic species as recognized by N&P, and that may not represent biological entities meriting protection. (3) Underprotected forms: species recognized by N&P that do not correspond directly to any current protected taxon but that are part of a protected BSC species listed in the NOM, at a lower risk category than presumably is merited under a PSC view point (e.g., Oaxaca Screech-owl Megascops lambi, subject to special protection as part of Pacific Screech-owl M. cooperi). (4) Unprotected forms: species recognized by N&P that have restricted geographic distributions but are not listed in the NOM because they are not currently recognized as biological species (Fig. 1b).

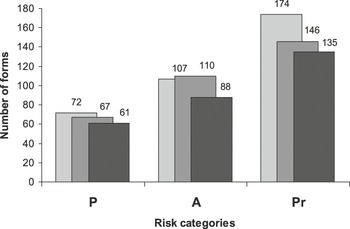

Finally, we used a chi-square analysis to analyze the differences among the risk categories (endangered, threatened and special protection) by species concept (Fig. 2) considering two datasets: a) the total number of protected forms (by risk category) per species concept, and b) the number of forms (by risk category) exclusively protected by each species list.

Figure 2. Number of forms protected under the three risk categories (P = endangered, A = threatened, and Pr = special protection) considering the biological species concept (light grey) and the phylogenetic species concept (dark grey). Black indicates the forms protected by both concepts.

Results

Of the 371 bird taxa listed in the NOM (Appendix 1 in Supplementary materials), 277 correspond to species and 94 to subspecies (note that 12 of these protected subspecies are included within 10 of the 277 protected species; however, as stated in methods, those were counted independently; Fig. 1a). In N&P, these numbers correspond to 298 species, of which 269 are concordant protected species and 29 are concordant protected subspecies (e.g., Jabiru Jabiru mycteria or San Lucas Robin Turdus migratorius confinis, forms recognized by both NOM and N&P, Fig. 1b).

We identified 47 discordant protected forms, most of them Baja California subspecies of widespread taxa (e.g., a local form of Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias sanctilucae, Appendix 1 in Supplementary materials). Two of these forms are included within a protected full biological species with distinct risk category: Northern Aplomado Falcon Falco femoralis septentrionalis and a form of Great Curassow Crax rubra griscomi.

The 28 under-protected phylogenetic species (Appendix 1 in Supplementary materials) include an interesting set of forms that exist in isolation in mountain ranges or islands, like White-breasted Hawk Accipiter (striatus) chionogaster, Salle's Quail Cyrtonyx (montezumae) sallei, forms of Band-tailed Pigeon Patagioenas (fasciata) vioscae, Yellow-headed Amazon Amazona (oratrix) tresmariae and Turdus (migratorius) confinis, among others.

Considering their restricted distributions, 11 phylogenetic species (Unprotected forms; Fig. 1b, Table 1) are considered good candidates for official protection, although not accorded any protected status previously. Such forms include phylogenetic species like Roadside Hawk Buteo gracilis or Vizcaino Thrasher Toxostoma arenicola, two examples that will be discussed below.

Table 1. List of unprotected phylogenetic species which are not included in the NOM.

Based on the two species lists (BSC and PSC), the variation among numbers of total forms changed respectively from 72 to 67 for “endangered”; from 107 to 110 for “threatened”, and from 174 to 146 for “special protection” (Fig. 2) which do not differ statistically (χ22 = 1.34, P = 0.511). However, considering the number of forms exclusively protected by each of the species lists, the differences vary from 11 to 6 for “endangered”, 19 to 22 for “threatened”, and 39 to11 for “special protection” (Fig. 2), differences that are statistically distinct (χ22 = 9.79, P = 0.007).

Discussion

Lack of correspondence between taxonomic lists based on different species concepts may generate inconsistencies in the identification of taxa that merit protection according any particular legislation. Our results suggest that the current number of forms listed by the NOM (371; Fig. 1a) decreases to 337 species considering the PSC (Fig. 1b). This reduction follows the exclusion of discordant forms (i.e. poorly differentiated subspecies) even considering the inclusion of unprotected taxa. However, an increase in the list from 277 BSC forms (Fig. 1a) to 337 PSC taxa (Fig. 1b) occurs only if the species category is considered. Modifications of this magnitude based on the application of alternative species taxonomy would make a significant difference, not only for conservation strategies and priorities for the Mexican avifauna (Peterson and Navarro Reference Peterson and Navarro1999), but also worldwide (Dillon and Fjeldså Reference Dillon and Fjeldså2005).

The discordant protected forms identified include 47 subspecies that represent minor variants of broadly distributed species, therefore not considered by N&P as species. As an example, the California Gnatcatcher Polioptila californica has been subdivided differently in three treatments (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Friedmann, Griscom and Moore1957, Atwood Reference Atwood1991, Mellink and Rea Reference Mellink and Rea1994), rendering ambiguous infraspecific patterns of variation. P. c. atwoodi (ranging from west of the Sierra San Pedro Mártir to the US-Mexican border, Mellink and Rea Reference Mellink and Rea1994) is listed as “threatened”. However, Zink et al. (Reference Zink, Barrowclough, Atwood and Blackwell-Rago2000) found no genetic differentiation among these populations that might justify division below the species level. Indeed, even the validity of P. c. californica, the subspecies used as a flagship for habitat conservation in California, has been questioned: Zink et al. (Reference Zink, Barrowclough, Atwood and Blackwell-Rago2000) suggested a single, recently expanded population across the species's range.

Discordant protected forms also include widely distributed species containing well-differentiated sub-populations that deserve higher levels of protection. For example, the widespread Kentucky Warbler Oporornis tolmiei is categorized as threatened as a whole, based on an isolated breeding population that is differentiated genetically and morphologically from other populations of the species. This population remains taxonomically undescribed (Milá et al. Reference Milá, Girman, Kimura and Smith2000) and may best be added to the list of underprotected forms, based on its very restricted distribution in northeastern Mexico. Other such examples of discordant protection are listed in Appendix 1 in Supplementary materials.

Evidence of the existence of taxa that are underprotected or underappreciated throughout the world is becoming available more often as research in song, behaviour, and phylogeography develops. Examples of allopatric populations with long-term evolutionary independence, especially among montane and insular taxa that have coupled genetic and morphological differentiation associated with geographic breaks (e.g., Milá et al. Reference Milá, Girman, Kimura and Smith2000, García-Moreno et al. Reference García-Moreno, Navarro-Sigüenza, Peterson and Sánchez-González2004, Reference García-Moreno, Cortés, García-Deras and Hernández-Baños2006).

The vast majority of the underprotected forms detected by us result from lack of recognition of allopatric populations as separate species. For example, Yellow-headed Amazon Amazona oratrix is listed as endangered, but the form endemic to the Tres Marías Islands (A. tresmariae, sensu N&P) is listed only as threatened, even though it has a more restricted distribution and its population has been estimated as less than 800 birds (Howell Reference Howell2004). Eberhard and Bermingham (Reference Eberhard and Bermingham2004) came to the conclusion, based on molecular and plumage character analysis, that all Mesoamerican forms (including A. o. tresmariae and A. o. oratrix) should be considered as distinct units for conservation purposes. Therefore, threat status should be higher due to restricted distribution and small population size.

Another example involves the allopatric populations of the highly polytypic Emerald Toucanet Aulacorhynchus prasinus complex, presently listed as subject to special protection in Mexico. Although up to six subspecies have been described in Mexico (A. p. prasinus, A. p. virescens. A. p. wagleri. A. p. stenorhabdus, A. p. chiapensis and A. p. warneri; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Friedmann, Griscom and Moore1957, Winker Reference Winker2000), morphology (Navarro et al. Reference Navarro, Peterson, López-Medrano and Benítez-Díaz2001), and molecular characters (Puebla-Olivares et al. Reference Puebla-Olivares, Bonaccorso, Espinosa de los Monteros, Omland, Llorente-Bousquets, Peterson and Navarro-Sigüenza2008) converge on the conclusion that the Sierra Madre del Sur (Guerrero and western Oaxaca) A. p. wagleri should be accorded species status and ranked in a higher conservation category given its restricted range and low abundance. The application of BSC criteria may result in the restricted geographic distribution, narrow ecological range and small population size of such forms being overlooked, thus limiting also the assignation of conservation status.

Approximately 11 micro-endemic forms were identified by N&P that have been overlooked in any protection category (Fig. 1b, Table 1). For example, the form of Roadside Hawk Buteo [magnirostris] gracilis, endemic to Cozumel Island, is one of the most endangered Mexican bird taxa (Howell Reference Howell2004), yet has been ignored by the current legislation. Similarly, the Vizcaino Thrasher Toxostoma [lecontei] arenicola is well-differentiated in mtDNA characters and coloration (Zink et al. Reference Zink, Blackwell-Rago and Rojas-Soto1997), suggesting that the taxon is a different species, and the only bird endemic to the Vizcaino Desert of central Baja California. Another nine potentially endangered species (Table 1) were selected based only on restricted geographic distributions, so consideration of more and broader information it is necessary to corroborate their risk status.

In general, our analysis suggests that once a species is split or aggregated, its position in any of the priority listings of threatened and endangered species should be carefully reassessed, given that such changes could transform a biological species into a set of phylogenetic species, some of which may prove to be of very restricted distribution, inhabit isolated and endangered habitats, and/or have small population sizes.

Considering the protection scenarios based on the two species concepts, the amount of change in the number of total protected forms by risk category statistically remains the same (Fig. 2). However, considering the number of forms by risk category that are protected exclusively by each species concept, then the differences vary statistically. Thus, the major difference between lists is based on which forms are exclusively protected by each list. Differences between the two scenarios result mainly from the use of subspecies under BSC, leading to the incorporation of 75 forms at different levels (discordant and underprotected forms, Fig. 1b), representing almost 20% of the total BSC list.

As more studies find a lack of correspondence between subspecies boundaries and historical groups obtained by phylogenetic analyses, taxonomic recommendations resulted in that many subspecies are either synonymised, or given full species status, particularly in species showing continuous distributions and clinal variation and based in morphology, molecular, and vocal data sets (e.g. Barrowclough and Gutierrez Reference Barrowclough and Gutierrez1990, Zink Reference Zink1994, Marín Reference Marín1997, Burns Reference Burns1998, Pitman and Jehl Reference Pitman and Jehl1998, Friesen et al. Reference Friesen, Anderson, Steeves, Jones and Schreiber2002, Leger and Mountjoy Reference Leger and Mountjoy2003, García-Moreno et al. Reference García-Moreno, Navarro-Sigüenza, Peterson and Sánchez-González2004, Zink et al. Reference Zink, Rising, Mockford, Horn, Wright, Leonard and Westberg2005, Rising Reference Rising2007). Within this framework, governments compose endangered taxa lists based on the expertise of the scientific community. Scientists using diverse taxonomic criteria for recognition of forms that should be encompassed in the catalogues should devote their efforts to the goal of conserving biodiversity by compiling, advising, and commenting on such lists. However, the general resurvey of the world's avifauna under alternative species concepts in wide regions has only begun (see Christidis and Boles Reference Christidis and Boles2008 for Australia), and more taxa remain unstudied than those that have been subject of analysis, creating a notably unbalanced alpha taxonomy for the global avifauna (Navarro-Sigüenza and Peterson Reference Navarro-Sigüenza and Peterson2004, Peterson Reference Peterson2006). This problem has influenced conservation due to the use of subspecies that in diverse cases might not represent evolutionary units and processes at any scale, and the flaw of not detecting several significant conservation units.

Given that conservation priorities depend critically on the particular authority employed, and that mixed-species-concept prioritizations may yield unpredictable results as has been demonstrated for the endemic avifauna in Mexico (Peterson and Navarro Reference Peterson and Navarro1999) and the Philippines (Peterson Reference Peterson2006), we suggest that progress in delimitation of conservation units will be greatly improved by the advance in species concept debate, instead of being impeded by it (Winker et al. Reference Winker, Rocque, Braile, Pruett, Cicero and Remsen2007). We need agreement on the taxonomic basis for taxa to make risk categories comparable within and among countries, which would contribute to improvement in policies for bird conservation.

Acknowledgments

A. T. Peterson, R. M. Zink, N. Mercado-Silva, and J. F. Ornelas provided important comments on the manuscript. The staff of the Museo de Zoología, F. C., UNAM and Instituto de Ecología, A. C., encouraged the generation of this manuscript through discussions of subspecies concepts and conservation. Funding was obtained from SEMARNAT-CONACYT Sectorial Fund (C01-0265).