Introduction

Introduced rodents have wide-ranging negative impacts on biodiversity of the world’s islands (Atkinson Reference Atkinson and Moors1985, Croll et al. Reference Croll, Maron, Estes, Danner and Byrd2005, Jones et al. Reference Jones, Tershy, Zavaleta, Croll, Keitt, Finkelstein and Howald2008, Kurle et al. Reference Kurle, Croll and Tershy2008, Harper and Bunbury Reference Harper and Bunbury2015). In the last 50 years, rodent eradication has become a common tool to restore island ecosystems, and rodents have been eradicated from > 570 islands (DIISE 2016, Russell and Broome Reference Russell and Broome2016).

Although most well-planned eradication operations are now successful (DIISE 2016), there are still occasional failures (Parkes et al. Reference Parkes, Fisher and Forrester2011, Holmes et al. Reference Holmes, Griffiths, Pott, Alifano, Will, Wegmann and Russell2015). Failures tend to be more common on tropical than on temperate islands, but even a failed eradication operation generally results in a large, if temporary, reduction of the rodent population (Amos et al. Reference Amos, Nichols, Churchyard and Brooke2016). These temporary reductions in rodent abundance may allow plants and animals that are heavily affected by rodents to reproduce more successfully and survive in larger numbers (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Holmes, Butchart, Tershy, Kappes, Corkery, Aguirre-Muñoz, Armstrong, Bonnaud, Burbidge, Campbell, Courchamp, Cowan, Cuthbert, Ebbert, Genovesi, Howald, Keitt, Kress, Miskelly, Oppel, Poncet, Rauzon, Rocamora, Russell, Samaniego-Herrera, Seddon, Spatz, Towns and Croll2016). However, the effects of failed eradication operations are rarely documented, particularly on tropical islands (Keitt et al. Reference Keitt, Griffiths, Boudjelas, Broome, Cranwell, Millett, Pitt and Samaniego-Herrera2015).

Henderson Island (24°20’S, 128°20’W) is a 43 km2 raised coral atoll in the Pitcairn Islands of the South Pacific Ocean. The island is home to thousands of seabirds (Brooke Reference Brooke1995a, Reference Brookeb), and four endemic land bird species: Henderson Crake Zapornia atra, Henderson Fruit Dove Ptilinopus insularis, Henderson Lorikeet Vini stepheni, and Henderson Reed Warbler Acrocephalus taiti (Graves Reference Graves1992, Brooke Reference Brooke1995b), all of which are classified as ‘Vulnerable’ by IUCN. Pacific rats Rattus exulans were introduced during the period of Polynesian expansion around 1100-1400 CE (Weisler Reference Weisler1995), and have negative effects on Henderson’s avifauna through predation of chicks and eggs, and competition for food resources (Wragg and Weisler Reference Wragg and Weisler1994, Brooke Reference Brooke1995a, Brooke and Jones Reference Brooke and Jones1995, Jones et al. Reference Jones, Schubel, Jolly, Brooke and Vickery1995, Brooke et al. 2010). At least four bird species, including three doves (Columbidae) and a sandpiper (Scolopacidae), have become extinct on Henderson Island over the past 500 years since Polynesian colonisation, partly due to human consumption and the detrimental effects of introduced rats (Steadman and Olson Reference Steadman and Olson1985, Wragg and Weisler Reference Wragg and Weisler1994, Wragg Reference Wragg1995). The high biodiversity values place Henderson Island among the top priorities for restoration among the UK Overseas Territories (Dawson et al. Reference Dawson, Oppel, Cuthbert, Holmes, Bird, Butchart, Spatz and Tershy2015).

To avert further bird extinctions from Henderson, a rat eradication operation was carried out in August 2011 using the aerial broadcast of toxic grain-based bait pellets (Torr and Brown Reference Torr and Brown2012). Although this operation was performed to the highest standards, it did not succeed in killing all rats on Henderson, but the operation did reduce the abundance of rats enormously for about 1–2 years (Amos et al. Reference Amos, Nichols, Churchyard and Brooke2016, Bond et al. Reference Bond, Cuthbert, McClelland, Churchyard, Duffield, Havery, Kelly, Lavers, Proud, Torr, Vickery and Oppelin press).

Here, we examine the response of the island’s land bird community to the temporary alleviation of the effects of rats, and provide an updated status assessment of all four endemic land bird species of Henderson four years after a failed eradication operation. This study provides valuable information that allows assessment of any temporary beneficial or detrimental effects of a failed eradication operation.

Methods

Study area

Henderson Island is a flat, raised coral atoll in the subtropical Pacific Ocean with two main habitats - a near-shore beach and embayment fringe forest, and a central plateau roughly 30 m above sea level, and no permanent freshwater bodies (Pandolfi Reference Pandolfi1995, Waldren et al. Reference Waldren, Florence and Chepstow-Lusty1995). The island has a subtropical climate with erratic rainfall patterns and a total annual rainfall around 1,700 mm (Spencer Reference Spencer1995). The plateau substrate is fossilised coral with a largely uniform native vegetation consisting of stunted trees up to 5 m tall, mostly Pisonia grandis, Pandanus tectorius and Xylosma suaveolens (Waldren et al. Reference Waldren, Florence and Chepstow-Lusty1995), and a very dense understorey of tangled vines. The beach and the embayment forest (“beach back”) areas have a sandy substrate with a mixed vegetation dominated by broad-leaved shrubs (e.g. Tournefortia argentea) up to 3 m tall, and small stands of introduced coconut Cocos nucifera. Further details of the island’s habitats and plant communities can be found elsewhere (St. John and Philipson Reference St. John and Philipson1962, Paulay and Spencer Reference Paulay and Spencer1989, Waldren et al. Reference Waldren, Florence and Chepstow-Lusty1995, Brooke et al. 1996, Waldren et al. Reference Waldren, Weisler, Hather and Morrow1999).

Population monitoring

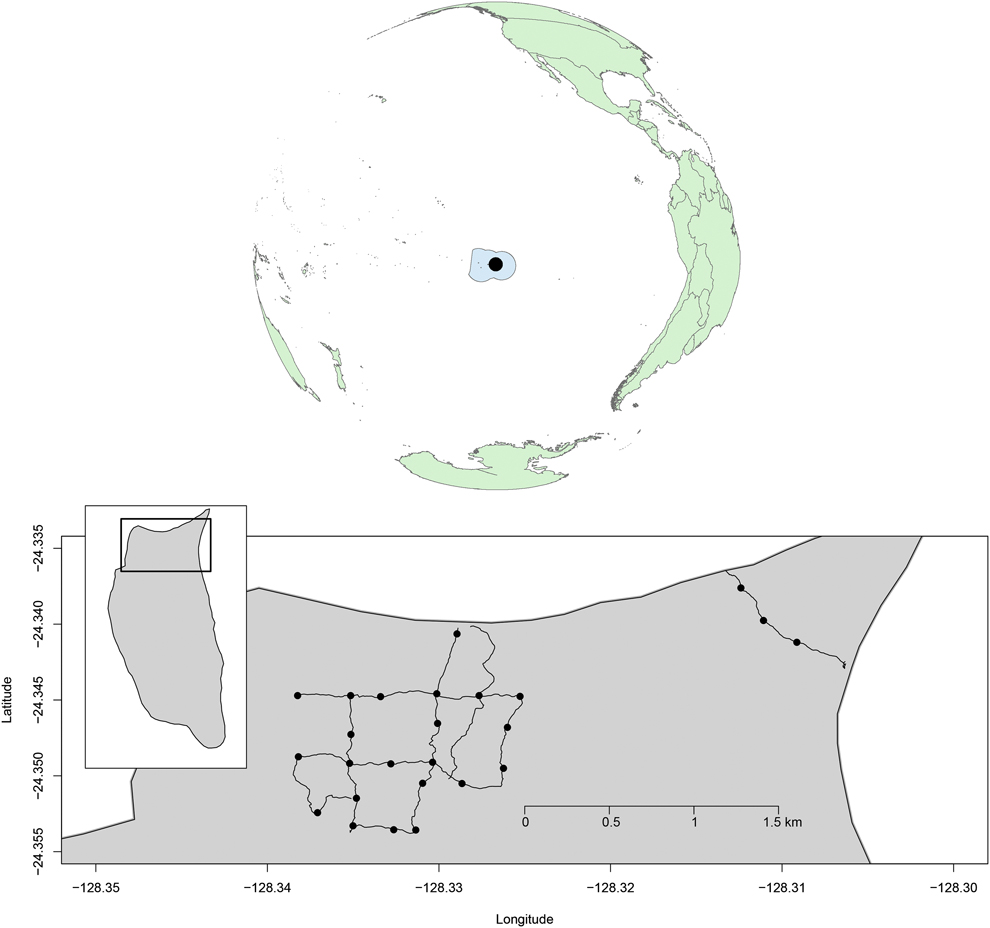

We monitored land bird abundance at 25 point-count locations spaced ∼250 m apart along an 8.6 km trail network on the north end of the island (Fig. 1). Difficulty in accessing Henderson Island meant that monitoring periods were not spaced equally through time. Surveys were conducted from August to November 2011 (immediately before and after the eradication operation from 11 to 22 August 2011), in November 2012, July and August 2013, and June–November 2015.

Figure 1. The Pitcairn Islands Exclusive Fisheries Zone, with Henderson Island (black circle), and detail of the northern part of Henderson Island showing the trail network and the locations where land bird point counts where conducted between 2011 and 2015 (black dots).

During each survey period, we conducted 2–3 surveys at each point count station within 5–7 days to maximise the chance that populations were demographically closed during the survey period. The timing of surveys varied among years: between 10:00 and 14:00 hrs (2011, 2012; all times UTC-8), or between 06:00 and 10:30 hrs (2013). To maximise comparability with previous survey efforts, at least one of the three repeat visits in each month in 2015 was in each of the two time intervals. We recorded all land birds that were detected visually or acoustically by 1–4 observers during a 10-minute period, and registered the date, time, and the observers conducting the survey to account for variation in detection probability among observers and over time. Henderson Crakes suffered considerable mortality during the eradication operation; their population recovery is described in detail elsewhere (Oppel et al. Reference Oppel, Bond, Brooke, Harrison, Vickery and Cuthbert2016), but they are included here to provide data on the entire extant land bird community.

At each point count location, we also recorded habitat variables that may have affected the detectability of bird species. We visually estimated the mean canopy height (in m), the maximum tree height within a 10-m radius (in m), and the mean height of the understorey (in m) to the nearest m, the density of the understory in three categories based on whether we could walk through the understory with ease, with difficulty, or not at all, and the proportion of the ground in a 5-m radius covered in leaf litter.

Estimation of land bird population changes over time

We estimated the abundance of each species around the point count stations using binomial mixture models (Royle and Nichols Reference Royle and Nichols2003, Kéry et al. Reference Kéry, Royle and Schmid2005, Royle et al. Reference Royle, Nichols and Kéry2005). Briefly, these models consist of two components which link the ecological state of interest (abundance of birds) and the observation process (detection probability) in a hierarchical fashion. The abundance component is modelled as a random Poisson process and estimates the size of the ‘superpopulation’ of birds, conceptually the total number of birds whose home range overlaps with the area around a sampling station where they can be detected by observers (Royle and Nichols Reference Royle and Nichols2003, Kéry et al. Reference Kéry, Royle and Schmid2005, Kéry and Schaub Reference Kéry and Schaub2012). The observation model component is conditional on the number of birds estimated at each sampling station, and estimates the probability of detecting an individual bird during a given point count based on repeated counts at a given site using binomial trials for each bird. Because we were interested in the temporal trajectory of land bird populations, we used the open-population binomial mixture model described by Kéry et al. (Reference Kéry, Dorazio, Soldaat, Van Strein, Zuiderwijk and Royle2009). We accounted for the unequal time difference between primary survey periods by first calculating the number of days that had elapsed between the mid-points of subsequent primary survey periods, and using that information to scale the population growth parameter to the period of 365 days to report annual population growth rates.

To account for variation in detection probability, we included relevant detection covariates for each species based on personal observations and other studies (Kéry Reference Kéry2008, Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, McIntyre and MacCluskie2013, Parashuram et al. Reference Parashuram, Oppel, Fenton, James, Daley, Gray, Collar and Dolman2015). We first conducted an exhaustive exploratory analysis to identify the environmental variables explaining the greatest amount of variation in our data (Table S1 in the online supplementary material), and used those variables in subsequent models assessing the population trend over time (Parashuram et al. Reference Parashuram, Oppel, Fenton, James, Daley, Gray, Collar and Dolman2015). We ran models including all combinations of variables and used Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) to select the most parsimonious model. For the Henderson Fruit Dove, we included the number of observers, density of the understorey, and mean canopy height (Table S1); for Henderson Reed Warblers, we included time of day, number of observers, and mean canopy height (Table S1); and for Henderson Lorikeet we included time of day, number of observers, mean canopy height, maximum tree height, understorey height, understorey density and litter cover (Table S1). The model used for Henderson Crake included mean canopy height, time of day, leaf litter, maximum tree height, understorey height, and the number of observers, as well as an additional correlation parameter to address the fact that members of a pair call to each other and are usually detected in pairs (Graves Reference Graves1992, Oppel et al. Reference Oppel, Bond, Brooke, Harrison, Vickery and Cuthbert2016).

We fitted all models in JAGS 4.2 via the R2jags package (Su and Yajima Reference Su and Yajima2015) in R 3.2.4 (R Core Team 2017). We ran eight Markov chains each with 250,000 iterations, discarded the first 150,000 iterations, and report posterior mean estimates and 95% credible intervals for annual population growth rate (λ), total abundance summed across all survey points, and detection probability averaged across survey points and repeat counts. To assess whether models provided an adequate fit to the data, we applied a Bayesian posterior predictive check (Gelman et al. Reference Gelman, Carlin, Stern and Rubin2004), and we report the Bayesian P-value as an indicator of model fit (Kéry and Schaub Reference Kéry and Schaub2012).

Extrapolation of global population sizes of endemic land bird species

The binomial mixture models that we used estimate the abundance of birds that can occur in the area around a survey point (Oppel et al. Reference Oppel, Cassini, Fenton, Daley and Gray2014). Because this area is not unambiguously defined and varies by species, the abundance estimates cannot be transformed into density estimates without making an explicit assumption about the area that is being sampled for each species. Historic surveys of land birds on Henderson Island provided total population sizes for the island. To facilitate a comparison with historic reports we extrapolated the total population size of each species in 2015 by making explicit assumptions about the area over which point counts would sample individuals. Although this area was unknown, we used previous descriptions of territory size and likely flight distance of each species (Graves Reference Graves1992, Brooke and Hartley Reference Brooke and Hartley1995, Brooke and Jones Reference Brooke and Jones1995, Jones et al. Reference Jones, Schubel, Jolly, Brooke and Vickery1995), combined with personal observations in the field, to specify a minimum and maximum radius that seemed plausible for each species. These radii are a combination of both detection and movement distances. For Henderson Reed Warblers, which have a quiet call and are an inconspicuous and slow-moving understorey species, we chose a radius of 50–100 m; for Henderson Fruit Doves, which have a quiet but far-carrying call and a larger home range we chose a radius of 100–150 m; for Henderson Lorikeet which can travel long distances very rapidly and have a loud screeching call we chose 150–350 m; for Henderson Crakes we chose a radius of 64–131 m based on radio-tracking information (Oppel et al. Reference Oppel, Bond, Brooke, Harrison, Vickery and Cuthbert2016). We emphasise that these assumed radii are not empirically determined, and do not allow a robust estimation of population size, but they provide reasonable upper and lower limits of likely population sizes that allow a qualitative comparison with historical data.

We used the specified radii around each point count location to calculate the sampled area for each species and converted the robust abundance estimates into an average density which we then extrapolated across the available habitat on the island. Available habitat was assumed to be approximately 75% of the 43 kmFootnote 2 island area (Brooke and Jones Reference Brooke and Jones1995). We emphasise that our estimates are not strictly comparable to those made previously because of methodological differences in how total population sizes were extrapolated, but they allow us to compare whether population sizes of land birds in 2015 were of the same order of magnitude as in the 1980s and 1990s. We report the number of individuals per ha, and adjust historical estimates, which were often reported as pairs per ha and were based on an incorrect island area.

Results

The models for land bird abundance fit the data well (Bayesian P-values = 0.39-0.76), and all parameters had ![]() $\hat{R}$ < 1.09. The number of Henderson Fruit Doves (λ = 1.077, 95% CI: 1.042-1.112) and Henderson Reed Warblers (λ = 1.212, 95% CI: 1.165–1.260) increased from 2011–2015, while Henderson Lorikeet showed no evidence of population change (λ = 1.046, 95% CI: 0.983–1.113; Fig. 2). The population of Henderson Crakes increased enormously in the aftermath of the anticipated mortality during the eradication operation (Oppel et al. Reference Oppel, Bond, Brooke, Harrison, Vickery and Cuthbert2016).

$\hat{R}$ < 1.09. The number of Henderson Fruit Doves (λ = 1.077, 95% CI: 1.042-1.112) and Henderson Reed Warblers (λ = 1.212, 95% CI: 1.165–1.260) increased from 2011–2015, while Henderson Lorikeet showed no evidence of population change (λ = 1.046, 95% CI: 0.983–1.113; Fig. 2). The population of Henderson Crakes increased enormously in the aftermath of the anticipated mortality during the eradication operation (Oppel et al. Reference Oppel, Bond, Brooke, Harrison, Vickery and Cuthbert2016).

Figure 2. Estimated population size (mean ± 95% credible intervals) of all four endemic Henderson Island land bird species around 25 point count locations from 2011 to 2015, after an unsuccessful eradication operation in August 2011. Note that Henderson Crake abundance in 2011 was artificially reduced (Oppel et al. Reference Oppel, Bond, Brooke, Harrison, Vickery and Cuthbert2016).

We estimated a mean of 260 Henderson Fruit Doves around the 25 point-count locations in 2015, 146 Henderson Lorikeets, 181 Henderson Reed Warblers, and 228 Henderson Crakes (Oppel et al. Reference Oppel, Bond, Brooke, Harrison, Vickery and Cuthbert2016). In general, the extrapolated global population sizes of all four land bird species were of the same order of magnitude as previous estimates from the 1980s and 1990s (Table 1).

Table 1. Total population estimates of Henderson Crake, Henderson Fruit Dove, Henderson Reed Warbler, and Henderson Lorikeet extracted from the literature and extrapolated from estimated abundances in 2015 based on different sampling radii around point count locations.

Population estimates from 2015 were estimated using binomial mixture models based on data from point counts, and are the mean and 95% credible interval (CrI; see text for details). Original population estimates from 1987 used an incorrect island area of 3600 ha, those from 1991 used 3700 ha, and we corrected these estimates to the actual island area of 4308 ha. Estimates from 1987, and those for Henderson Reed Warbler in 1991 assumed all island area was suitable; all other estimates assumed 75% of habitat was suitable (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Schubel, Jolly, Brooke and Vickery1995).

These abundances, combined with likely detection distances resulted in population estimates of 4,476–10,072 Henderson Fruit Doves, 554–3,014 Henderson Lorikeets, 7,194–28,776 Henderson Reed Warblers, and 4,960–20,783 Henderson Crakes in 2015 (Table 1).

Discussion

Although the eradication operation on Henderson Island in 2011 failed to eliminate all rats on the island, land bird populations in 2015 were of the same order of magnitude as in the 1980s and 1990s, and the extinction risk of the four endemic land bird species and Henderson Petrel Pterodroma atrata (Oppel et al. Reference Oppel, Lavers, Donaldson, Forrest, McClelland, Bond and Brooke2017) is unlikely to have fundamentally increased or decreased. The smallest land bird species, the Henderson Reed Warbler, experienced a substantial population increase following the eradication operation, which may have been facilitated by the temporary reduction of the Pacific rat population.

The rat population on Henderson Island was previously estimated to be 104,000–172,000 individuals, and was reduced to 60–80 individuals during the eradication operation in 2011 (Cuthbert et al. 2012, Amos et al. Reference Amos, Nichols, Churchyard and Brooke2016, Bond et al. Reference Bond, Cuthbert, McClelland, Churchyard, Duffield, Havery, Kelly, Lavers, Proud, Torr, Vickery and Oppelin press). Subsequent monitoring indicated that rat density in the embayment forest may have recovered to pre-operation levels within less than two years, while the plateau rat population may have required a longer period to reach carrying capacity, or may have been substantially overestimated in the past (Bond et al. Reference Bond, Cuthbert, McClelland, Churchyard, Duffield, Havery, Kelly, Lavers, Proud, Torr, Vickery and Oppelin press). For native biodiversity, there may have been a period of 1–2 years during which consumption of flowers, fruit, eggs, or young by rats would have been substantially lower. The mechanisms by which a temporary reduction of the rat population may have benefitted the endemic land bird species vary depending on the nature of the interaction between birds and rats.

Rats are likely significant predators of Henderson Reed Warbler eggs and chicks (Brooke and Hartley Reference Brooke and Hartley1995), and rats may also compete for seeds, fruits, and invertebrates which Henderson Reed Warblers consume at certain times of the year (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Moller, Ramsay and Wait1984, Graves Reference Graves1992, Sugihara Reference Sugihara1997, Shiels and Drake Reference Shiels and Drake2011, Pender et al. Reference Pender, Shiels, Bialic-Murphy and Mosher2013, Harper and Bunbury Reference Harper and Bunbury2015). The number of Henderson Reed Warblers around point count locations more than doubled between 2011 and 2015 to an island-wide population of around 7,000–28,000 individuals (Table 1, Figure 1).

Rats may compete with frugivores by removing or damaging fruit (García Reference García2002, Shiels and Drake Reference Shiels and Drake2011), and reducing rodent abundance can have a positive effect on frugivorous birds. New Zealand Pigeons Hemiphaga novaeseelandiae have increased breeding success and are more abundant when rats are removed or controlled, mostly as a result of a reduction in direct predation, but also because of an increase in abundant food sources previously suppressed by rats (Clout et al. Reference Clout, Denyer, James and McFadden1995, James and Clout Reference James and Clout1996, Innes et al. Reference Innes, Nugent, Prime and Spurr2004). Henderson Fruit Doves consume fruits < 18 mm in size, mostly Procris pedunculata, with smaller contributions from several other species, including Xylosma suaveolens, Cyclophyllum barbatum, and Psydrax odorata (Brooke and Jones Reference Brooke and Jones1995), all of which showed an increase in seedling counts in vegetation monitoring plots between the time of the bait drop in 2011 and subsequently in 2013 and 2015 (Lavers et al. Reference Lavers, McClelland, MacKinnon, Bond, Oppel, Donaldson, Duffield, Forrest, Havery, O’Keefe, Skinner, Torr and Warren2016). Because Henderson Fruit Doves are thought to be limited by food supply (Brooke and Jones Reference Brooke and Jones1995), an increase in fruit abundance may have contributed to the Henderson Fruit Dove population increase from 2011 to 2015.

However, we found no population change for Henderson Lorikeet, which also feeds on a variety of smaller fruit, flowers, nectar from Timonius uniflorus, and Scaevola taccada, and arthropod larvae (Trevelyan Reference Trevelyan1995). While Henderson Lorikeets were probably least affected by human habitation and the introduction of rats on Henderson (Trevelyan Reference Trevelyan1995, Weisler Reference Weisler1995), their nesting habits are poorly known and it is unclear how vulnerable Henderson Lorikeet eggs and chicks may be to rat predation. In New Zealand, the Red-fronted Parakeet Cyanoramphus novaezelandiae, a species with a similar natural history to the Henderson Lorikeet, increased once rats had been removed from breeding islands, presumably because of reduced predation (Graham and Veitch Reference Graham, Veitch, Veitch and Clout2002, Miskelly and Robertson Reference Miskelly, Robertson, Veitch and Clout2002). However, the increase was much steeper on an island where Norway rats R. norvegicus were removed (Miskelly and Robertson Reference Miskelly, Robertson, Veitch and Clout2002) than on an island where only Pacific rats were removed, and the larger Norway rat may have a substantially higher impact through the predation of adult females in nest cavities. Our data could therefore indicate that Henderson Lorikeets are not substantially affected by Pacific rats on Henderson, but we emphasise that Henderson Lorikeets are also the most mobile of the four land bird species, and estimates of population size therefore lacked the precision needed to assess whether populations had changed.

For both the Henderson Reed Warbler and the Fruit Dove, extrapolated population sizes in 2015 were of similar magnitude as those in the 1980s and 1990s (Table 1), despite the documented population increase of both species between 2011 and 2015. We therefore caution that the increase may have been due to natural fluctuations. In late 2010 and early 2011, the island experienced a 6-month drought that may have naturally suppressed vegetation, invertebrates and bird abundance, and our counts at the beginning of the time series in August 2011 may therefore have happened at a time when the population sizes of some land bird species were lower than usual (Oppel et al. Reference Oppel, Bond, Brooke, Harrison, Vickery and Cuthbert2016). Because no comparable point-count data exist from before 2011 that would allow us to quantify the natural fluctuation of land bird populations in response to environmental conditions, understanding the mechanism for the population changes in Henderson Reed Warbler and Henderson Fruit Dove between 2011 and 2015 is complicated by the fact that population recoveries may have occurred either due to increasing food availability following the end of a natural drought or the temporary suppression of rodent numbers, or a combination of both factors.

Henderson Crake’s population recovered rapidly following the unintended but expected high mortality during the eradication operation, and is discussed in detail elsewhere (Oppel et al. Reference Oppel, Bond, Brooke, Harrison, Vickery and Cuthbert2016). This recovery was facilitated by a population held captive in situ during the eradication operation, and subsequently released once it was safe to do so (Oppel et al. Reference Oppel, Bond, Brooke, Harrison, Vickery and Cuthbert2016). Rails can be heavily impacted by invasive rodents, but respond rapidly when rodents are eradicated, or reduced in abundance (Wanless et al. Reference Wanless, Cunningham, Hockey, Wanless, White and Wiseman2002, Donlan et al. Reference Donlan, Campbell, Cabrera, Lavoie, Carrion and Cruz2007, Hockey et al. Reference Hockey, Wanless and von Brandis2011). On Henderson Island, rats likely depredate small chicks (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Schubel, Jolly, Brooke and Vickery1995), and the temporary reduction in rat numbers from 2011 to 2013 may have aided in the crake’s recovery.

Our study highlights the importance of monitoring native bird species both before and after interventions to reveal previously unknown or suspected impacts of introduced species (Lorvelec and Pascal Reference Lorvelec and Pascal2005). The responses of ecosystems to a reduction or cessation in competition or predation pressure by introduced rodents can be complex with unanticipated outcomes (Rayner et al. Reference Rayner, Hauber, Imber, Stamp and Clout2007, Bergstrom et al. Reference Bergstrom, Lucieer, Kiefer, Wasley, Belbin, Pedersen and Chown2009), and very few eradication projects invest adequate resources in pre- and post-operational monitoring (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Holmes, Butchart, Tershy, Kappes, Corkery, Aguirre-Muñoz, Armstrong, Bonnaud, Burbidge, Campbell, Courchamp, Cowan, Cuthbert, Ebbert, Genovesi, Howald, Keitt, Kress, Miskelly, Oppel, Poncet, Rauzon, Rocamora, Russell, Samaniego-Herrera, Seddon, Spatz, Towns and Croll2016, Brooke et al. Reference Brooke, Bonnaud, Dilley, Flint, Holmes, Jones, Provost, Rocamora, Ryan, Surman and Buxton2018). We have shown that the four endemic land bird species of Henderson Island were as abundant in 2015 as they had been in the 1980s and 1990s, but that there may have been temporary benefits of the failed conservation intervention. We encourage future island restoration programmes to establish robust monitoring schemes in advance of an eradication operation to document the natural variability of population sizes and continue monitoring following the operation to allow an unambiguous assessment of the effect of conservation management.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270918000072

Acknowledgements

We thank the Government of the Pitcairn Islands for permission to work on Henderson Island, P. Warren, S. O’Keefe, M. Rodden, D. Brown, and A. Brown for assistance in the field, and J. Hall, A. Schofield, J. Kelly and C. Stringer for general support. The crews of the Braveheart, Claymore II, Teba, and Xplore, provided transportation to and from Henderson. The David and Lucile Packard Foundation, Darwin Plus: Overseas Territories Environment and Climate Fund, British Birds, generous donors, and the RSPB, the UK partner in BirdLife International, helped to fund our research. Comments from three anonymous reviewers improved this manuscript.