Introduction

The White-breasted Guineafowl Agelastes meleagrides Bonaparte, 1850 (Aves: Galliformes: Numididae) is one of 15 known bird species endemic to the Upper Guinea Forest (BirdLife International 2003, 2007), which once covered West Africa from southern Senegal to Togo (Sayer et al. Reference Sayer, Harcourt and Collins1992). Larger populations of the species are probably confined to remnants of continuous forest in Sierra Leone, Liberia and Côte d'Ivoire (BirdLife International 2007). Recent observations have been made in Ghana (L. H. Holbech pers. comm.), but its occurrence in Guinea remains doubtful (Gartshore et al. 1995).

White-breasted Guineafowl probably occurred throughout the forest area from Sierra Leone to Ghana (Collar and Stuart Reference Collar and Stuart1985). After the reduction of the Upper Guinea Forest in the 1960s (Martin Reference Martin1991) continuous primary forest now largely consists of fragments of less than 200 km2 (Sayer et al. Reference Sayer, Harcourt and Collins1992; Holbech Reference Holbech2005) and this loss of habitat as well as hunting pressure are thought to be the main threats to the existing populations of White-breasted Guineafowl (Francis et al. Reference Francis, Penford, Gartshore and Jaramillo1992). Little is known about its ecology (available information is compiled in Francis et al. Reference Francis, Penford, Gartshore and Jaramillo1992). Birds live in small flocks which move slowly through the forest, searching the leaf litter for invertebrates and possibly also seeds and fruits. Before dusk they settle to roost in thin understorey trees at heights of 6–15 m. Interestingly, no nest has yet been scientifically described, either for the White-breasted Guineafowl or for its sister species the Black Guineafowl Agelastes niger Cassin, 1857 (Urban et al. Reference Urban, Fry and Keith1986, Raethel Reference Raethel1991, Francis et al. Reference Francis, Penford, Gartshore and Jaramillo1992, Madge and McGowan Reference Madge and McGowan2002). Even today it is impossible to say with certainty whether the former nests on trees or on the ground, like most Galliformes (Bechinger Reference Bechinger1964, Francis et al. Reference Francis, Penford, Gartshore and Jaramillo1992). Young birds have been observed from the end of November until the end of May. No relationship between the time of the year and the size of the young was found, suggesting aseasonal breeding (Francis et al. Reference Francis, Penford, Gartshore and Jaramillo1992).

Taï National Park (NP) in Côte d'Ivoire certainly holds an important part of the global population of the species and is therefore of importance to its conservation (Gartshore et al. 1995). It is classified as ‘Vulnerable’ on the IUCN Red List (IUCN 2007). Detailed surveys on White-breasted Guineafowl are rare (see Allport et al. Reference Allport, Ausden, Hayman, Robertson and Wood1989 for Gola Forest in Sierra Leone and Francis et al. Reference Francis, Penford, Gartshore and Jaramillo1992 for Taï NP, Côte d'Ivoire) and previous estimates of population density in Taï NP were based on data restricted to the western park region (Francis et al. Reference Francis, Penford, Gartshore and Jaramillo1992). The objective of this study was therefore to re-evaluate population density within the area of Taï NP and the adjacent N'Zo Faunal Reserve (N'Zo FR) in Côte d'Ivoire, to detect habitat preferences and to assess the influence of poaching on the population of White-breasted Guineafowl. We used data from line transects in three sectors of the protected area, differing in: 1) amounts of rainfall received - lower in the north of the Taï region vs. wetter in the south (van Rompaey Reference van Rompaey1993); 2) the degree of disturbance from logging, as logged forest in the north vs. primary forest in the south (Fishpool Reference Fishpool, Fishpool and Evans2001); and 3) hunting pressure - high in the east vs. low in the west (Hoppe-Dominik Reference Hoppe-Dominik1997, Refisch and Koné Reference Refisch and Koné2005).

Based on previous studies (Francis et al. Reference Francis, Penford, Gartshore and Jaramillo1992, Demey and Rainey Reference Demey, Rainey, Alonso, Lauginie and Rondeau2005, Dowsett-Lemaire and Dowsett 2007 in Klop et al. Reference Klop, Lindsell and Siaka2008), we expected that population density of White-breasted Guineafowl might be higher in drier forests north of Taï than in wetter forests in southern Taï NP. Furthermore, we expected White-breasted Guineafowl to be affected by poaching since groups are reported to be easily shot by imitating their grouping call which causes individuals to assemble rather than spread as in Crested Guineafowl Guttera pucherani (Bechinger Reference Bechinger1964, and reports from hunters in Ghana and Eastern Côte d'Ivoire). The impact of poaching on the population density should be greatest in the eastern areas of Taï NP where hunting pressure is reportedly highest (Refisch and Koné Reference Refisch and Koné2005, Caspary et al. Reference Caspary, Koné, Prouot and de Pauw2001, Hoppe-Dominik Reference Hoppe-Dominik1997). While Francis et al. (Reference Francis, Penford, Gartshore and Jaramillo1992) conclude that population density in selectively logged forests is similar to unlogged primary forests, Bechinger (Reference Bechinger1964) and Allport et al. (Reference Allport, Ausden, Hayman, Robertson and Wood1989) argue that population density is much lower in areas of past logging disturbance. The latter say that White-breasted Guineafowl is unable to adapt to the denser undergrowth of heavily disturbed forests. We expected our results to add useful information to this discussion by allowing us to compare data across three sectors, and to estimate effects of the factors of hunting and logging separately.

Methods

Study area

The study area comprises Taï NP (3,300 km2; 5°51’ N, 7°23’ W) and the adjacent N'Zo FR (930 km2; 6°15’ N, 7°14’ W) in southwestern Côte d'Ivoire, close to the border with Liberia (Fishpool Reference Fishpool, Fishpool and Evans2001; Gartshore et al. 1995). Taï NP holds the largest continuous remnant of Upper Guinea Forest and is thus of extreme importance for the conservation of many bird species endemic to this biome (Gartshore et al. 1995). Twelve of the 15 bird species endemic to the Upper Guinea Forest are currently reported to live in Taï NP (BirdLife International 2003, 2007).

Until this research was carried out, the area has never been controlled by rebel or loyalist armed forces and the park staff was largely able to continue operating (IUCN/UNESCO 2006). Adverse impacts on Taï NP's fauna, flora or infrastructure due to the national crisis caused by the civil war in 2002 should therefore have been only temporary. In contrast, poaching has always occurred and agricultural activities and, to a lesser extent, small surface gold-mining along rivers were other imminent threats to the park's unique fauna and flora (Avit et al. Reference Avit, Pedia and Sankaré1999, IUCN/UNESCO 2006). To prevent agricultural cultivation inside the park, 630 km2 of buffer zones (Avit et al. Reference Avit, Pedia and Sankaré1999) almost completely surrounding the park were established in 1977 (IUCN/UNESCO 2006). In these zones, any hunting, settling or new plantation development and even harvesting of non-timber forest products were officially prohibited. It is expected that the pressure from the growing human population has already affected these zones (IUCN/UNESCO 2006).

Several forest reserves (Forêt Classées, FC), are found in the south (FC de la Haute Dodo 2,000 km2, 4°54’ N, 7°18’ W; FC Rapide Grah 2,042 km2 5°05’ N, 7°08’ W) and the west (FC du Cavally, 1,890 km2 6°10’ N, 7°47’ W; Grebo National Forest, 2,510 km2 5°36’ N, 7°52’ W, in Liberia) of Taï NP (van Rompaey Reference van Rompaey1993, Alonso et al. Reference Alonso, Lauginie and Rondeau2005). However, forest cover within these FCs might only be a fraction of their total surface area (Refisch and Koné Reference Refisch and Koné2005).

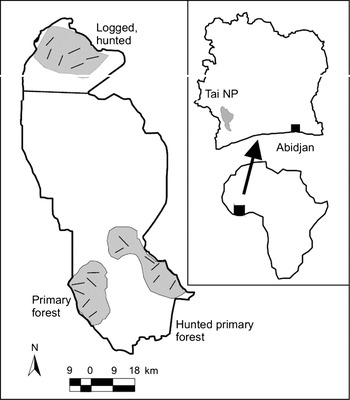

Data were collected in three different sectors of the protected areas, two in Taï NP and one within N'Zo FR, representing ca. 20% (Taï) and 50% (N'Zo) of the protected areas (Figure 1). These sectors vary considerably in the degree of hunting pressure and the impact of timber extraction. In N'Zo FR timber was extracted until 1992 (Fishpool Reference Fishpool, Fishpool and Evans2001). The two Taï NP sectors are located in the south of the park, one at the southwestern and one close to the southeastern boundary. Both were covered with primary forest at the time of the study (Fishpool Reference Fishpool, Fishpool and Evans2001), but the southeastern sector was strongly influenced by poaching, which should be of much less importance in the southwestern sector (Hoppe-Dominik Reference Hoppe-Dominik1997, Refisch and Koné Reference Refisch and Koné2005).

Figure 1. Map of the study area showing the three sectors and the location of the sampled transects (adapted from Radl Reference Radl, Girardin, Koné and Yao2000).

These sectors also represent a SW-NE oriented rainfall and vegetation gradient. Forest composition at N'Zo FR principally differs from the southern areas of Taï NP because N'Zo FR receives less annual precipitation (van Rompaey Reference van Rompaey1993). The rainfall gradient ranges from about 2,000 mm yr−1 in the southwest of Taï NP to 1,600 mm yr−1 in the northeast of N'Zo FR (van Rompaey Reference van Rompaey, Riezebos, Vooren and Guillaumet1994). The dry season becomes gradually longer from the coast of Côte d'Ivoire further inland (from a maximum of one arid month at the coast to three arid months at Taï (5°53’ N 7°20’ W) and precipitation during the driest month is significantly lower (van Rompaey Reference van Rompaey1993). Mean annual temperature is 26°C throughout the study area (Collar and Stuart Reference Collar and Stuart1988).

Fieldwork

In each of the three sectors, six line transects were placed randomly, each with a length of 4 km. Experienced teams consisting of three observers walked each transect on average 43 times between January 2000 and December 2001. A transect was sampled twice during a day of observation, between 07h00 and 12h00 and 15h00–18h00. At N'Zo FR a total of 924.5 km of survey effort was completed during the two-year survey. At the southwestern site in Taï NP, the distance covered totalled 1,314.1 km and at the southeastern site a total of 644.0 km was walked. Group size and perpendicular distance from the transect midline to the nearest 50 cm were noted for all detections of White-breasted Guineafowl groups.

Data analysis

We modelled the detection probability using Distance 5.0 (see Buckland et al. Reference Buckland, Anderson, Burnham, Laake, Borchers and Thomas2001). Since the number of sightings of White-breasted Guineafowl was relatively low, we combined the data gathered in 2000 and 2001 for each transect to increase the precision of our estimates of detection probability.

A hazard-rate key provided the best fit to the detection function. The model was selected using Akaike's Information Criterion (AIC), chi-squared goodness-of-fit-test and visual examination of histograms to assure an adequate representation of close-to-the-line distance intervals. We truncated data to a width of w = 15.5 m (1.25% of the data were excluded). Detection probability was modelled globally fitting a detection function to distance data from across strata (see Buckland et al. Reference Buckland, Anderson, Burnham, Laake, Borchers and Thomas2001), resulting in an AIC = 255.5, an effective strip width (ESW) = 8.4 m and a detection probability of P a = 0.53. Resolution of estimates of encounter rate, group density, cluster size and individual density was at the sector level.

Results

Our results show that White-breasted Guineafowl was not distributed uniformly throughout the study area (see Table 1). In the hunted primary forest sector in the southeast of Taï NP only one group of five individuals was recorded on one occasion, while it was regularly recorded in the other two sectors (23 observations at N'Zo FR and 55 observations in the southwestern sector of Taï NP).

Table 1. Survey effort, Number of detections per sector (n), encounter rate (ER, [n km−1]), group density (GD, [flocks km−2]), expected cluster size (ECS, [ind./flock]) and individual density (D, [ind. km−2]) of White-breasted Guiineafowl in the Taï region, Côte d'Ivoire. Limits of the 95% confidence interval are given in brackets.

Group density varied notably between sectors. In N'Zo FR, an average of 1.5 group(s) km−2 was estimated compared to 2.5 groups km−2 in the unhunted primary sector of Taï NP. However, there was a much higher cluster size in N'Zo FR, ranging from 1 to 38 individuals per group with an average of 22.3 ind. per group (95% CI: 19.3–29.4). This more than doubled the values from the undisturbed, but wetter southwest of Taï NP (range: 1–23 ind./group; average: 9.1 ind./group, 95% CI: 7.2–9.7).

Individual density was with 32.9 ind. km−2 at N'Zo FR, ca. one-third higher than in the unhunted primary forest (22.6 ind. km−2, Z test Z = 1.88, two-tailed P = 0.030).

Discussion

Distribution and density

The high individual density in N'Zo FR (32.9 birds km−2) strongly suggests that the White-breasted Guineafowl is not confined to undisturbed primary forest areas and that former sightings in logged forest (Allport et al. Reference Allport, Ausden, Hayman, Robertson and Wood1989) potentially were not isolated cases. Our findings confirm the assumption by Francis et al. (Reference Francis, Penford, Gartshore and Jaramillo1992) that White-breasted Guineafowl occurs at high densities in areas of past disturbance. It would, however, be far too speculative to attribute the high population density exclusively to the fact that forest in N'Zo FR has formerly been logged. The species is apparently absent from forest plantations in Côte d'Ivoire (Gartshore et al. 1995). Several studies from the Sundaic region in Southeast Asia and from French Guiana in South America showed that terrestrial litter-gleaners are particularly vulnerable to the effects of logging (Thiollay Reference Thiollay1992, Reference Thiollay1997, Grieser Johns Reference Grieser Johns1996, Lambert and Collar Reference Lambert and Collar2002). Studies of bird communities and different feeding guilds in several forest types in East Africa and Madagascar also showed that they are negatively affected by timber extraction (Plumptre et al. Reference Plumptre, Dranzoa, Owiunji, Fimbel, Grajal and Robinson2001). Thus in our case, other factors, maybe related to vegetation composition or rainfall patterns, might be of higher importance in explaining why the logged sector had a higher bird density than both unlogged sites.

Demey and Rainey (Reference Demey, Rainey, Alonso, Lauginie and Rondeau2005) who conducted a rapid assessment programme in the FC de la Haute Dodo (south of Taï NP) and in the FC du Cavally (west of the park) discovered White-breasted Guineafowl at both sites, also proving the existence of populations in logged forest areas outside the national park. White-breasted Guineafowl was found to be more abundant at the FC du Cavally, which is situated about 100 km north of the FC de la Haute Dodo, receiving less annual precipitation (van Rompaey Reference van Rompaey1993).

Forests in N'Zo FR are even drier than those at Cavally and certainly than those in the south of the national park. The southern sectors of the park are likewise influenced much by floods of the river Hana and its tributaries. Apparently, White-breasted Guineafowl avoids wet valley bottoms (Francis et al. Reference Francis, Penford, Gartshore and Jaramillo1992).

Drier forests usually support a considerably thicker litter layer and potentially a richer arthropod fauna than wet evergreen forests (L. H. Holbech pers. comm.).

The differences in cluster size detected between N'Zo FR and the south-western sector of Taï NP are also of interest. Before this study, the largest White-breasted Guineafowl group ever recorded was a flock of 29 birds (Francis et al. Reference Francis, Penford, Gartshore and Jaramillo1992). The largest flock we observed consisted of 38 birds and was found at N'Zo FR. Other Galliformes showed altered flock behaviour due to changed habitat conditions which might also influence flock size (Shin-Jae and Woo-Shin Reference Shin-Jae and Woo-Shin2003), but reproductive and social behaviour of the species is largely unknown.

Poaching

Although not addressed in our study, there is much evidence of increasing poaching levels in the Taï region. One reason is the dramatically growing human population in areas surrounding the park. Many immigrants, primarily resettled Baoulé from the centre and the north of Côte d'Ivoire and refugees from Liberia, have settled since 1970, causing an increase in population of more than 10% annually (Koch Reference Koch, Riezebos, Vooren and Guillaumet1994). Secondly, the growing large-scale commercial market for bushmeat in Côte d'Ivoire has turned poaching into an important source of income in the region (Caspary et al. Reference Caspary, Koné, Prouot and de Pauw2001). Lastly, increased pressure on game is triggered by advances in hunting technology which result in more efficient hunting (Refisch and Koné Reference Refisch and Koné2005).

The extremely low number of detections of the species in the hunted sector at the southeastern border of the park is an alarming signal and in line with Refisch and Koné (Reference Refisch and Koné2005) who conclude that also other wildlife has disappeared over much of the eastern part of Taï NP.

Initially, we assumed that hunting pressure might also be high at N'Zo FR due to the infrastructure created to extract timber (Robinson et al. Reference Robinson, Redford and Bennett1999). Our results could imply, however, that at least for White-breasted Guineafowl, the impact of poaching is much smaller in this area than in the southeastern sector of Taï NP. Whether accessibility is really a problem for hunters remains unclear but at least roads are apparently underdeveloped given the usual infrastructure created by logging companies.

Nevertheless, the near-absence of the species in the southeastern sector of the NP suggests that illegal hunting is likely to pose a major threat to the White-breasted Guineafowl population in Taï NP. The birds might not be the main target of poachers (Francis et al. Reference Francis, Penford, Gartshore and Jaramillo1992) since prices for guineafowl are usually low compared to other game (Allport et al. Reference Allport, Ausden, Hayman, Robertson and Wood1989) but the cost-benefit relationship could be influenced by the species’ gregarious habits which allow groups rather than individuals to be targeted. In addition to commercial hunting with guns, subsistence hunting and the use of snares are also likely to affect the population (Allport Reference Allport1991).

Population size

Any estimate of population size based on our data is necessarily neither exact nor statistically tenable, because we can only assume that our line transects covered representative proportions of favourable and less favourable habitats. An educated guesswork approach might use the following assumptions: (i) population data from the southwestern sector of Taï NP (22.6 ind. km−2) might be representative for about 50% of the NP (1,650 km2); (ii) data from the southeastern sector of Taï NP (0.5 ind. km−2) might be representative for the other half of the park area (1,650 km2); and (iii) data from the N'Zo FR (32.9 ind. km−2) might be characteristic for the whole faunal reserve (930 km2). Based on these assumptions, we obtained an overall individual density of 16.2 ind. km−2 for the whole study area and a total population size of roughly 68,700 individuals (range based on 95% CI of density estimates: 42,400 to 119,800) for Taï NP and N'Zo FR combined (4,230 km2).

This value is higher than the population size estimate of Francis et al. (Reference Francis, Penford, Gartshore and Jaramillo1992), who calculated a maximum potential population of 30,000–40,000 individuals for Taï NP and the surrounding buffer zone. Their estimate included 3,400 km2 of national park area and 660 km2 of peripheral zone. Differences between the estimates arise partly from the area included (4,060 km2 Francis et al. Reference Francis, Penford, Gartshore and Jaramillo1992; 4,230 km2 this study), but mainly from the fact that our calculations include observations from different sectors inside the protected area. Values used for the estimate in Francis et al. (Reference Francis, Penford, Gartshore and Jaramillo1992) were based only on observations next to the IET (Institut d'Ecologie Tropicale) scientific station in the west of the park and some sightings at Hana and Meno River in the wetter southwestern region. Our study showed, however, that the population in N'Zo FR is particularly large, underlining the conservation importance of the N'Zo FR.

Management

Certainly, the first priority to save the unique fauna of Taï NP is to control poaching more effectively. A much better conservation awareness by the park staff is needed to reach this goal. Access points to the park, routes and preferred game species should be recorded every time a group of poachers is detected in order to obtain a clearer picture of their methods and to quantify their influence on the fauna (see also IUCN/UNESCO 2006). Animal husbandry and/or alternative wildlife friendly farming of resilient and prolific rodents and duikers has to be promoted through community-based programmes (Refisch and Koné Reference Refisch and Koné2005). Efforts to control the large-scale commercial market are also of great importance in reducing poaching in the Taï region, but it is managerially more complicated as it entails prosecution of bushmeat operators.

The ‘forêts classées’ surrounding the National Park suffer even more than N'Zo FR from agricultural encroachment, uncontrolled logging and poaching (Alonso et al. Reference Alonso, Lauginie and Rondeau2005). To ensure that enough appropriate habitat for White-breasted Guineafowl is protected, drier forest areas such as the ‘forêts classées’ and N'Zo FR should be awarded a higher conservation status. N'Zo FR should be seen as a part of Taï NP as proposed in the joint IUCN/UNESCO mission report (IUCN/UNESCO 2006). Stronger legal protection status is an advantage in the fight against poaching and agricultural encroachment, especially if the human population in the surroundings of this area continues to grow.

Increased protection and restoration of the ‘forêts classées’ would contribute to the construction of a protected area network connecting the Taï NP population of White-breasted Guineafowl to populations in Liberia (in Grebo National Forest and Sapo NP). A bilateral project to create this ‘green sickle’ (van Rompaey Reference van Rompaey1993) is a challenge for future conservation of Upper Guinea Forest bird endemics.

To prevent the ‘forêts classées’ from being a ‘sink’ for the local fauna, timber extraction needs to be reduced to a level of minimum impact and hunting activities need to be controlled more effectively, by involving neighbouring communities as well as strengthening law enforcement. The conservation of endangered species should be more effectively included in integrated conservation programmes (IUCN/UNESCO 2006) by incorporating biodiversity goals not only into park management but also in buffer zone management through increased awareness creation at the level of project staff.

Conclusions

As for the conservation of wildlife in general, the first priority for the conservation of White-breasted Guineafowl is the reduction of poaching in Taï NP and adjacent areas, to ensure the survival of a viable core population. Not only the poachers themselves but also traders, markets and restaurants profiting from the illegally hunted meat need to be addressed. Community-based programmes might provide appropriate alternatives to bushmeat and might help in the process of forming legal wildlife management but it is also essential that existing conservation regulations are enforced.

The incorporation of N'Zo FR into the national park, as proposed in the IUCN/UNESCO mission report (2006) would provide a more adequate protection status to a considerable part of the population of White-breasted Guineafowl.

A network of forests connecting Taï NP in Côte d'Ivoire and Sapo NP in Liberia is another important step in enhancing long-term survival of White-breasted Guineafowl. Remaining forest areas next to the Liberian border, such as the FC du Cavally and the FC de la Haute Dodo, should be protected more strictly. Further agricultural encroachment into these areas has to be stopped and wildlife-friendly, agroforestry-based production systems should be encouraged to create a ‘green bridge’ between Liberia and Côte d'Ivoire.

Also further research is needed to determine the main mortality factors of White-breasted Guineafowl and factors influencing social structure and behaviour. Indeed any ecological information gathered on this species would facilitate an optimal conservation strategy.

Acknowledgements

We thank Taï National Park and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) for supporting wildlife monitoring as part of their management activities. Matthias Waltert is currently supported by a grant from the Volkswagen Foundation. We also thank Benjamin G. Krause, Nicolai G. Brock, Jasmine Braidwood and Juliane Geyer, as well as the reviewers Lars H. Holbech and Hugo Rainey for useful information and improvements to our manuscript.