Introduction

Within the lower Senegal valley there are large tracts of land that used to be subjected to a dynamic flooding regime, but are now cut off from the water. The historical situation allowed for a variety of traditional land uses, such as pastoralism and extensive fisheries and was characterised by high biodiversity. The loss of seasonal flooding has had serious consequences for local livelihoods and led, for example, to a major loss in winter and staging habitats for birds (Triplet and Yesou Reference Triplet and Yesou2000, Zwarts et al. Reference Zwarts, Bijlsma, van der Kamp and Wymenga2009).

This paper focuses on one of these areas, the Ndiael (Réserve Spéciale d’Avifaune du Ndiael (RSAN) 16°10–16°18N and 16°00–16°07W), a bird reserve in the delta of the Senegal River. The Ndiael is formally designated as a Ramsar Convention wetland of international importance, but is presently on the list of degraded sites (Montreux Record d.d. 04/07/90; Faye Reference Faye2015). The Ndiael is part of the UNESCO Man and Biosphere Reserve “Réserve de Biosphère Transfrontalière du Delta du Sénégal” (RBTDS), commonly declared by the two bordering countries, Senegal and Mauritania, and recognised by the United Nations since 27 June 2005. The concepts and ideas behind the RBTDS are further explained in Borrini-Feyerabend and Hamerlynck (Reference Borrini-Feyerabend and Hamerlynck2011).

Within the RBTDS there are three National Parks (NP): Diawling NP in Mauritania, Djoudj NP and Langue de Barbarie NP, both in Senegal. In addition, there are several reserves. Especially relevant for this study are Djoudj NP and Diawling NP, and to a certain extent the Trois Marigots hunting area (three elongated and parallel basins situated between the Ndiael and Saint Louis). These are the remaining wetland areas with seasonal flood dynamics in the lower delta, and are extremely important for wintering migrant and colony breeding birds (Zwarts et al. Reference Zwarts, Bijlsma, van der Kamp and Wymenga2009, Triplet et al. Reference Triplet, Diop, Sylla and Schricke2014). They serve as a spatial reference for the Ndiael under restored conditions and as examples for the type of water management required.

The cause of the degraded state of the Ndiael is a lack of seasonal flooding according to many sources (e.g. Humbert et al. Reference Humbert, Mietton and Kane1995, Kane et al. Reference Kane, Ndiaye, Mbaye and Triplet1999, de Naurois Reference de Naurois1965). Humbert et al. (Reference Humbert, Mietton and Kane1995) set out the relevant options for its restoration. One option is a seasonal inundation of the Ndiael, which would strengthen the ecosystem services, benefit and empower the rural communities, and enhance biodiversity. As of 2015, major hydrological investments are being made in the region, which is reason to review the historical developments and document the baseline situation.

The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of 1) the efforts that have been taken to restore the wetlands in the Ndiael, 2) the baseline ecological situation, now that fundamental hydrological changes are being implemented and 3) the threats and tensions that need to be tackled, when implementing the scheme of water management. This study provides information to feed the public debate on how the scarce water resources in this part of the Sahel region should be used in a sustainable way for food and ecosystems.

Historical developments and attempts for restoration

Until the 1950s, the Ndiael never dried out, and included an area of open water varying from 10,000 to 30,000 ha (de Naurois Reference de Naurois1965). The three sources of water that used to feed the Ndiael (see Figure 1) were cut off over time for different reasons. The Yéti Yone from the north became cut off in 1956 (Kotschoubey Reference Kotschoubey2000, Zwarts et al. Reference Zwarts, Bijlsma, van der Kamp and Wymenga2009) by the construction of a dike around Lac de Guiers. The access from the north-west became blocked when the national highway was constructed in the years 1950–1959, and the link to the Trois Marigots in the south became regulated by a series of dams which reduced spillovers. By 1965 the Ndiael had dried out as a result of these developments (de Naurois Reference de Naurois1965).

Figure 1. Map of reserve boundaries and hydrological system in the lower Senegal valley. The reserve boundary in 2014 is an approximation based on an image by SAED in 2014.

At the beginning of the 1990s a drain was created underneath the national highway (Figure 1) that supplies excess drainage water from Kassack (2,250 ha) and Grande digue (3,000 ha) rice fields in the north-west, flooding some 100 ha according to Kane et al. (Reference Kane, Ndiaye, Mbaye and Triplet1999). A small channel in the north, the ‘canal Idrissa’, supplied a trickle of water to the village at the northern boundary of the reserve. So in all these decades, the only water reaching the Ndiael was rainfall, supplemented with some river input from the drain and the Trois Marigots.

By 1961 the first studies estimating the costs of reflooding the Ndiael were done by the Mission d’Aménagement du Senegal (M.A.S.; de Naurois Reference de Naurois1965). Such studies were repeatedly put forward in later years, for example by Mietton et al. (Reference Mietton, Humbert and Richou1991), Kane et al. (Reference Kane, Ndiaye, Mbaye and Triplet1999), Kotschoubey (Reference Kotschoubey2000), Tecsult International (2006), and Association Inter Villageoise Ndiael (2008). In 1994 the OMPO, a European institute for the management of wild birds and their habitats, took practical action, and supported the digging of a small channel in the south, reconnecting the Trois Marigots to the Ndiael (Kane et al. Reference Kane, Ndiaye, Mbaye and Triplet1999). Water actually reached the central and deepest part of the reserve, the so-called ‘cuvette centrale’ in 1996–1997 when the flood was strong. As of 1998 a new weir between the Djeuss river-branch and the Trois Marigots subsystem allows for the quick filling up of the Trois Marigots and a significant flow towards the Ndiael when the flood is strong in the Senegal river (Kane et al. Reference Kane, Ndiaye, Mbaye and Triplet1999). In 2010 the local population, together with the reserve authorities, reduced some of the blockades (sand dunes and the invasive plant cattail Typha domingensis) in the Yéti Yone, which coincided with heavy rains (Figure 2A) and contributed to a serious flood (6,200 ha in October 2010) after six years of drought (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. A) The yearly deviation from the average sum of rainfall in St Louis 1984–2014 (long term average is 281 mm), and B) Developments in rainfall and inundated area. To calculate the inundated area, we used an algorithm (AWEInsh formula; Feyisa et al. Reference Feyisa, Meilby, Fensholt and Proud2014). Total study area is 52,000 ha.

The government of Senegal is very aware of the strategic and economic importance of water management in the hydrological system of the Lac de Guiers and the Ndiael-Yéti Yone sub-system (PDMAS/SAED 2009). It established a water authority (Office du Lac de Guiers, OLAG) at the end of 2010, that should ensure sustainable water management and the restoration of ecosystems. This authority has acquired funding for an integrative project, and the ecological restoration of the Ndiael is one of the most important objectives (Kitane et al. Reference Kitane, Gbeli, Ba, Soumare, Ebono and Diom2013). OLAG is investing in hydraulic infrastructure that should allow for a regulated flow of water up to 5 m3/s to the core of the reserve. Quite unexpectedly, a large agro-business company (SENHUILE) was established in the area in 2012, after a de-classification of 26,000 ha of the reserve for that purpose by Presidential decree (declassification decree number 2012-822; Word Reference Word2014).

Rainfall and inundated area

Regional rainfall is low and very erratic, which is characteristic of the Sahel (Zwarts et al. Reference Zwarts, Bijlsma, van der Kamp and Wymenga2009, figure 2A for St Louis). The long term average rainfall in St Louis over the years 1984–2014 was 281mm (119 SD). For Ross-Béthio, the rainfall station nearest to the Ndiael, the long term average is a little lower (262 mm for the years when data are available). The correlation between rainfall in Ross Béthio with that from St Louis is positive but the strength is poor (n = 18, R2 = 0.13). However, the yearly deviation from the average sum of rainfall in St Louis is presented in Figure 2A, because there was no uninterrupted series for Ross Béthio. Rainfall has a strong seasonal pattern with highest values in September (Fall Reference Fall2015). Evaporation varies between 1,400 and 1,900 mm/yr between 1983 and 2012 in St Louis (Fall Reference Fall2015).

The inundated surface area in the Ndiael was estimated for several months from 1984 to 2015, using the algorithms provided by Feyisa et al. (Reference Feyisa, Meilby, Fensholt and Proud2014). We used the ‘no shade’ algorithm for all images until and including 2013 and the ‘shade’ algorithm thereafter, because of a change in data provided by Landsat TM8 images in comparison to the previous types. The selection of images was made such that it allowed us to arrive at the best possible estimate for maximal inundated surface area in each of the years studied. Assuming that maximum inundation would occur in October, we concentrated on images from October and November. If the inundated area was higher than 1,000 ha in any of these months we also estimated the inundation in January. We only selected images with cloud cover < 10% and visually inspected those for the presence of clouds in the study area. For the years 1985 and 1987–1998 we did not succeed in obtaining images that met our criteria, mainly due to a malfunctioning of the sensor in the Landsat mapper (www.usgs.gov).

The area inundated fluctuates strongly within and between years (figure 2B). In the month of January it is always small (< 510 ha), but it may be well over 5,000 ha in October (years 2000 and 2010). In the years studied it never arrived at the values mentioned by de Naurois (Reference de Naurois1965). When studying the images in detail it appears that the water indeed originates from the sources mentioned above: rainfall supplied with river input via the Trois Marigots (year 1999), the Drain (years 2003, 2005, 2009, 2010, 2013) and the Yéti Yone (year 2013). A sequence of six years from 2004 until 2009 showed inundations of limited surface area, i.e. less than 1,200 ha. The inundation of 2010 (6,227 ha) coincided with investments made by local people to remove blockades in the Yéti Yone, and indeed some water flowed through the old riverbed. Nonetheless, the majority of the inundated area was to be explained by above average local rainfall and input via the Drain. October 2013, however, was characterised by a bigger flood (2,750 ha) than October 2012 (1,589 ha), in spite of lower annual rainfall. Again water arrived via the Yéti Yone (pers. obs.), but this time in larger quantities as a combined result of the hydrological works for the new agro-business company SENHUILE and the removal of more barriers in the watercourse of the Yéti Yone by local people. It cannot be deduced exactly from the satellite images what quantities of water originated from the drain, but it appears that input via the drain should not be neglected. In January 2014, the inundated area was still 509 ha, which is the highest area inundated in this month since the start of the data series.

Current state and potential

Social context

The majority (70%) of people in the 32 villages in or near the Ndiael are pastoralists of Peulh origin (Fall Reference Fall2015). The Wolof are among the other relevant ethnic groups near the reserve, with 27% of the population. In total there are an estimated 21,000 inhabitants that have a strong link to the Ndiael (Fall Reference Fall2015). In 2014 there were an estimated 17,600 cattle and 22,100 goats and sheep. Some nomadic pastoralism still exists by nomads from the Ferlo region in the south-west, who may find water in the south of the Ndiael and the Trois Marigots (Faye Reference Faye2015). Pastoralism has suffered from degradation of the area, caused by the virtual absence of significant flooding, and the associated disappearance of flood recession cultures, perennial grasses and diminished production of leaves and fruits from the acacia trees.

Some inhabitants practise small scale irrigated agriculture or horticulture, but the absence of suitable infrastructure and equipment has thus far limited revenue (Kane et al. Reference Kane, Ndiaye, Mbaye and Triplet1999). Although some species of fish have disappeared (CSE 2008), and the area with permanent or seasonal water has become quite small, some fishing still takes place in the watercourses present, mainly by fishermen from Mali. The number of local fishermen is negligible. However, the increased flooding, that resulted from the hydrological works for the new agro-business company (see above), already appears to have brought more fish as of 2013 (no data). Hunting and eco-tourism are absent in the reserve and local craft only plays a minor role.

The local population in the 32 villages around the Ndiael is quite well represented in a local association of villages (AIV) that actively seeks to restore the ecological potential of the Ndiael and performs many activities to sensitise people, protect and restore their tree resources and monitor the ecological developments (Association Inter Villageoise Ndiael 2008, Bos et al. Reference Bos, Davids, Wade, Sow and Gueye2015).

Land cover

According to old IGN maps (year 1922) the Ndiael consisted of salt marsh. However, already in 1964 (BDPA et al. 1995 as cited in Kane et al. Reference Kane, Ndiaye, Mbaye and Triplet1999) the major part of the reserve was characterised by bare soil. In 2013 this is still the case (Table 1). The terrain map of 2013 is given in Figure 3. The map is based on Google images from 2013, updated by ground-truthing in January 2014. There are sand dunes in the south-west and the east (upland grassland with trees and shrubs) that harbour herbaceous vegetation, dominated by annual grasses and interspersed with trees (average tree canopy cover of 3% ± 0.4). Dominant trees are Acacia senegal, A. tortilis and Balanites aegyptiaca. The basin is characterised by bare soil, grassland with trees and shrubs (tree canopy cover 12.6% ± 1.4) and gallery forest (tree canopy cover 27% ± 3.5) around the temporary watercourses and small depressions. Here the dominant trees are Acacia nilotica and Tamarix senegalensis. Temporary water bodies, helophytic vegetation and aquatic vegetation, together add up to 3,200 ha in the current situation. As yet, the area dominated by Typha domingensis is negligible (67 ha). The new agro-business is mainly situated in, and allocated to, areas on the higher ground. Information derived from a terrain map for the year 2003 (Table 1; CSE 2008), is not inconsistent with these results, but since the methodology to produce both maps was not the same, the differences are not discussed.

Table 1. Surface area of terrain types in the Ndiael in 2003 (CSE 2008) and 2013 (own data). The 2003 map is part of a supervised classification from satellite imagery for the entire lower Senegal valley (CSE 2008), the 2013 map is based on a landscape guided approach using Google images from 2013, updated by ground truthing in the field in January 2014.

Figure 3. Terrain map of the Ndiael for the year 2013.

The surface of the central, and deepest parts of the basin, the ‘cuvette’ itself is estimated by Humbert et al. (Reference Humbert, Mietton and Kane1995) at 10,000 ha at a water level of 1.10 m above sea level. Another estimate of the area that may be flooded potentially is given by the area of terrain types that belong to the basin, within the reserve. This is estimated at 18,700 ha. Thus, in comparison to the inundations of the short-term past (Figure 2B), the flooded area in the reserve may increase by thousands of hectares, assuming that sufficient water can be transported to the Ndiael.

Birds and other fauna

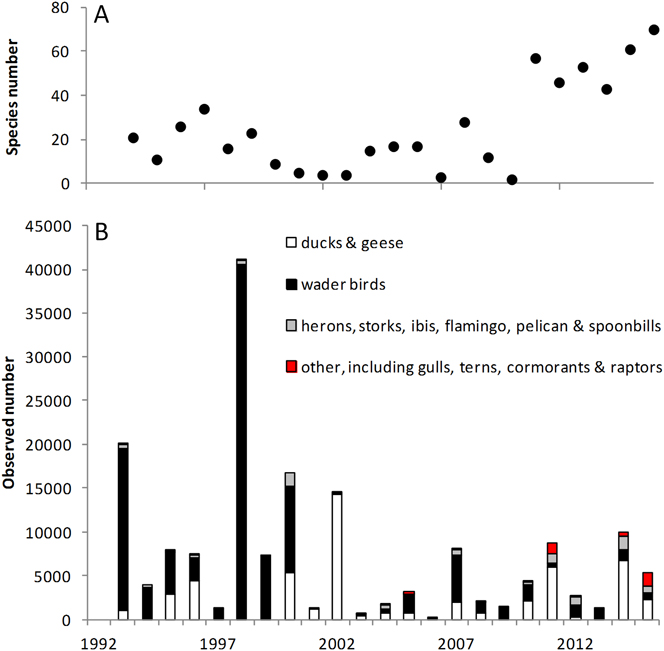

From 1993 there is an almost uninterrupted series of yearly counts of water birds in the Ndiael (Figure 4; Triplet et al. Reference Triplet, Diop, Sylla and Schricke2014). This series has been collected in the framework of the International Waterbird Census, executed in January each year. Most of the results have been collected by a local team consisting of volunteers and staff of the reserve. The consistency of the census data in the Ndiael varies with the availability of vehicles, binoculars and skilled people. Bird numbers strongly fluctuate both in total and between species. After 2009, there is a sudden change in the number of species observed (Figure 4A). This is known to be the result of a quantitative and qualitative investment in observer effort. Another reason for fluctuations is the change in availability of water in the Ndiael. In January of the years 2011 and 2014 the number of ducks and geese is particularly high (6,000–7,000 approximately, Figure 4B), caused by the considerable inundations at the end of the preceding years (Figure 2B). Due to these inundations, there was a relatively high water availability in the depressions of the former floodplain.

Figure 4. A) The observed number of species, and B) the number of birds observed per species group during the International Waterfowl Census in the Ndiael. Data courtesy of P. Triplet (Triplet et al. Reference Triplet, Diop, Sylla and Schricke2014). Observer effort has varied between years.

Over the past five years Garganey Anas querquedula were most numerous, with average numbers above 1,000 individuals. Except for the Eurasian Spoonbill Platalea leucorodia, the numbers nowadays are only a fraction of what was recorded in the past. In the period 1958–1965, Morel and Roux (Reference Morel and Roux1966) observed tens of thousands of Northern Pintail Anas acuta and Garganey as well as thousands of Black-tailed Godwit Limosa limosa and Greater Flamingo Phoenicopterus roseus, species that averaged only 37, 2048, 53 and 44 individuals respectively in the period 2010–2015. Nonetheless, five species are likely to surpass the 1% criterion for the international importance of wetlands according to the Ramsar Convention (Bos et al. Reference Bos, Davids, Wade, Sow and Gueye2015). These are Fulvous Whistling Duck Dendrocygna bicolor, Squacco Heron Ardeola ralloides, Black Stork Ciconia nigra, Eurasian Spoonbill and maybe Egyptian Goose Alopochen aegyptiaca.

In order to further establish a quantitative baseline, the bird fauna was inventoried using monthly point-transect counts for more than two years. This inventory revealed the frequency of occurrence of 194 species and demonstrates which bird species are present in addition to the waterfowl censused annually (Bos et al. Reference Bos, Davids, Wade, Sow and Gueye2015). The counts demonstrate that the habitat in the Ndiael is mostly dry and terrestrial in the current situation. The most frequently observed species are thus, for example, Red-billed Quelea Quelea quelea, Sand Martin Riparia riparia and Crested Lark Galerida cristata. Red-billed Quelea, a gregarious species, occurs in the highest densities of all and is treated as a pest species by the authorities, who kill them and destroy their nest locations.

Wild vertebrate fauna is rare in the Ndiael. The original large herbivore and carnivore species have disappeared, as is the case almost everywhere in West Africa (Prins and Olff Reference Prins, Olff, Newberry, Prins and Brown1998). In 2013 and 2014, patas monkey Erythrocebus patas, jackal Canis sp., African savanna hare Lepus crawshayi, marsh mongoose Atilax paludinosus and warthog Phacochoereus aethiopicus were observed in the reserve, as well as the reptiles West African Nile monitor Varanus niloticus and rock python Python sebae. Another 10 small vertebrate species, amongst which common genet Genetta genetta and African civet Civettictis civetta, but also spotted hyena Hyena crocuta crocuta were encountered by the local people in the last ten years (CSE 2008). Fish species are listed in Baldé (2007, as cited in Fall Reference Fall2015).

Opportunities and threats

Restored flows of water have the potential to bring back much of the resources that were previously lost. People are already eating fish that are caught in the Ndiael, something that has not been possible for years. A regeneration of trees and shrubs is observed that may provide important forage in the dry season for cattle. If perennial grasses should return, the forage availability per unit area becomes even larger. With the increased presence of water the availability of raw material for artisanal use will increase (Hamerlynck and Duvail Reference Hamerlynck and Duvail2003). The local people furthermore expect to gain from eco-tourism. These assumptions are corroborated by the information from the nearby example of Diawling NP (Mauritania), where economic activity was enhanced in many ways when the water returned (Hamerlynck and Duvail Reference Hamerlynck and Duvail2003; cf. Scholte Reference Scholte2005). The revitalisation of the Ndiael should thus result in a structural improvement for local pastoralists, smallholders and fishermen. The artificial flooding will be a very strong means to counteract climate change. Finally, the Ndiael has the potential to be a breeding area for colony breeding birds and a staging site for many more wintering migrants than it is now (Triplet et al. Reference Triplet, Diop, Sylla and Schricke2014), analogous to the case of the Logone floodplain restoration in Cameroon (Scholte Reference Scholte2006) and the Diawling NP (Hamerlynck and Duvail Reference Hamerlynck and Duvail2003; Triplet et al. Reference Triplet, Diop, Sylla and Schricke2014). Next to the Diawling and Djoudj National Parks, the Ndiael may provide the third safe haven for these groups of birds within the RBTDS. That could significantly reduce the risk of a failing year for their populations, in terms of breeding success or overwinter mortality.

In terms of threats, with increased water flows and the recently established large-scale agro-business, more people will undoubtedly be attracted to the area (cf. Scholte Reference Scholte2003). As a result of the conversion to intensive irrigated agriculture, large tracts of the reserve have lost most of their value as grazing land. This greatly increases the pressure on the remaining grazing resources with overgrazing and excessive cutting of branches as the main direct risk. Current water quality is at risk due to the input of nutrients and residues of pesticides from discharge of neighbouring and upstream irrigation schemes. The new agro-business may further exacerbate this, and will have strong repercussions regarding water availability, disturbance and social tension. These threats are nicely summarised in Word (Reference Word2014) and Fall (Reference Fall2015). Furthermore, unless the inundations are strictly alternated with prolonged dry periods, there is a very realistic danger that T. domingensis will develop dense stands in the watercourses and depressions. This has happened all over in the lower Senegal valley (Cogels et al. Reference Cogels, Coly and Niang1997; Kloff and Pieterse Reference Kloff and Pieterse2006) blocking waterways and access to water (OMVS and HaskoningDHV 2013) and reducing biodiversity (Sidaty Reference Sidaty2005). Finally, wind erosion may play a negative role by blocking the free flow of water towards the Ndiael.

Updated management plan

In consultation with local stakeholders, the reserve authorities (RSAN) have outlined their vision for the future management (Faye Reference Faye2015). The plan is highly comparable to previous management plans formulated for the area by Kane et al. (Reference Kane, Ndiaye, Mbaye and Triplet1999) and Association Inter Villageoise Ndiael (2008) in the sense that it aims for the restoration of the ornithological potential of the site, a rational use of natural resources by traditional activities of fishing, pastoralism and an active approach to promote reforestation. It is more specific than the previous management plans in that it explicitly opts for a seasonal rather than permanent inundation, options that were left open for public debate by Humbert et al. (Reference Humbert, Mietton and Kane1995). Seasonal inundation is seen as a key prerequisite in recreating diversity of habitats and enhancing biodiversity, while preventing the spread of waterborne diseases and infestation by Typha.

Management recommendations

The basic idea behind a seasonal inundation of the Ndiael still holds. By refilling natural depressions, such as the Ndiael, the water is put to use for the benefit and empowerment of the rural communities and the strengthening of ecosystem services and biodiversity in the Ndiael. Moreover, it will result in a a) reduced inundation risk in the lower parts of the city of St Louis downstream, b) an enhanced availability of forage for livestock, fish and habitat for wild fauna, and c) in a significant strengthening of the UNESCO Man and Biosphere reserve in the Senegal Delta (RBTDS), as next to the Djoudj and Diawling national parks, the Ndiael area will grow to be a third stronghold for wildlife and waterfowl populations.

However, given the annual and seasonal variation in the availability of water, as well as the suitability of the low-lying wetland zones for agro-economic development, there are competing demands around the use of land and water for intensive agriculture, versus pastoralism, fisheries and ornithological purposes. These interests are not necessarily opposing each other, as long as they are managed in an equitable and integrative way, taking into account the interests of local populations.

So, while the investments in the necessary hydrological infrastructure are being made by OLAG (year 2015 and 2016), it is recommended to maintain and improve the discussion with local stakeholders on how to understand, tackle and solve the above mentioned tensions. It will be useful to formulate ecological and socio-economic objectives suitable for the Ndiael, and monitor them together with local stakeholders. This should preferably be organised in a formal management structure. In doing this, much can be learned from the experiences in nearby Djoudj (Fall et al. Reference Fall, Hori, Kan and Diop2003) and Diawling national parks (Hamerlynck and Duvail Reference Hamerlynck and Duvail2003; Parc National du Diawling 2013). In particular, the recommendation by Hamerlynck and Duvail, that development issues are to be taken as seriously as environmental issues, is underlined. It is recommended to support the local population in their long-term protection of the natural resources and the development of sustainable economic activities.

Conclusions

The Ndiael became isolated from the natural flood regime of the Senegal river in the 1960s. For more than fifty years there has been only a limited inflow of water. But even in the current degraded state its remaining water bodies have important ecological value for resident and wintering migrant birds, as well as other resident fauna. The potential of the reserve for the provision of resources and biological diversity is much larger, as can be deduced from historical and spatial reference records. With limited effort and investment, the local population has achieved some increases in the inundated area, setting the stage for much larger investments within the framework of a recently started scheme run by the governmental water authority, OLAG. The baseline situation was mapped and a local team is monitoring the changes in habitat and bird density. Parallel to these developments, almost half of the reserve was declassified for the benefit of a large agro-business company. The increased pressure on the remaining grazing grounds, and the ecological threats associated with their activities provide a challenge for long-term sustainable protection and development of the Ndiael, unless the different interests are managed in an integrative way. In the new setting it will be essential to mitigate the tensions between this large scale irrigated agriculture, small holder interests and ecological restoration. This will require a continuous dialogue.

Acknowledgements

We are greatly indebted to the local team of the Association Inter Villageoise Ndiael (AIV) and the Reserve spéciale d’avifaune du Ndiael (RSAN) that performed the ecological monitoring, especially Coumba Ly-Tiamm, Abdoulaye Ka, Makhmout Fall, Ousseynou Niang, Babacar Diagne, Idrissa Ndiaye, and Paul Robinson. We furthermore thank Paul Brotherton, Dibocor Dione, Babacar Faye, Mahmoudou Tall, Moctar Wade, Aye Fall, five anonymous reviewers and Patrick Triplet. The support from Eddy Wymenga and Jaring van Rooijen has been very instrumental. This work was funded by Vogelbescherming Nederland (grant number P00098-C110067) and the Ecosystem Alliance Program Senegal (grant number 1232-005-002).