Introduction

Policymaking is classically understood as a long-term endeavour: since significant effort is invested in designing an optimal policy, once it has been successfully implemented the default is for it to stay in place unless circumstances arise that require it to be amended or repealed. However, a long history of sunset clauses presents a parallel mode of policymaking, in which a predetermined timeframe is established after which the policy will expire unless actively renewed.

Times of emergency often give rise to rights restricting temporary legislation. The recent COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the adoption of such temporary measures in many countries.Footnote 1 While the pandemic may justify the adoption of temporary emergency measures in countries where the spread of the virus was extensive, important questions arise as to the short- and long-term implications of enacting such temporary measures. To what extent does the temporary nature of these measures affect the willingness of individuals to approve restrictions that they would otherwise not condone? Moreover, what are the longer-term effects of adopting such restrictive measures on the likelihood of prolonging them or adopting other restrictions later in the future?

Despite the antiquity of the phenomenon, only recently has the attention in the academic literature turned into what has been termed the ‘golden age of scholarship on temporary legislation’ (Bar-Siman-Tov, Reference Bar-Siman-Tov2018b), with a surge of historical, comparative and normative research. Although some connections have been drawn between the behavioural literature and temporary policy, no experimental research targeted at exploring the behavioural underpinnings of making temporary policy has been conducted.

The present experiments are, to our knowledge, the first attempts to empirically test some of the behavioural implications of making temporary policy (for some existing behavioural but not experimental work on the topic, see Fagan & Bilgel, Reference Fagan and Bilgel2015; Zamir, Reference Zamir2015; Fabbri & Faure, Reference Fabbri and Faure2018). In a series of three experiments, we investigate the effect of time – both prospectively and retrospectively – on the willingness to approve rights-restricting policy. We focus on a particular class of temporary legislation, which is implemented as a response to extreme circumstances and as a tool to mitigate the infringement of human rights. Specifically, we examine the prospective effect of temporary legislation by investigating whether willingness to approve new measures increases when these measures are presented as temporary as opposed to permanent. From a retrospective standpoint, we examine whether willingness to extend temporary measures that are already in place exceeds willingness to approve new measures.

General motivations for using temporary measures

It has been stated that sunset clauses are used for reasons ‘ranging from pragmatic, to institutional to strategic’ (Gersen, Reference Gersen2007). The academic literature generally cites three types of benefits that sunset clauses can potentially have (Finn, Reference Finn2010): informational benefits (the possibility of incorporating additional information collected over time into the policymaking process), deliberative benefits (the possibility that both decision-makers and the general public will devote additional time and attention to debating the policy) and distributive benefits (distribution of responsibility between present and future policymakers as well as distribution of power between the implementers of the policy and the overseers).

According to most theorists, temporary measures are often tied to experimental policymaking as a way of encouraging innovation and learning. Making policy temporary lowers the costs of policymaking, thus allowing greater risk-taking, and the renewal process sets predetermined points for review of the policy, which can be used as a mechanism for incorporating additional information, thereby making possible evidence-based policymaking (Bar-Siman-Tov, Reference Bar-Siman-Tov2018a). Temporary provisions are also viewed as a mechanism for increasing accountability for delegated power by requiring periodic oversight and control, which can also be used to ‘reinvigorate stagnant bureaucracies’ (Mooney, Reference Mooney2004).

In addition, policymakers often view temporary measures as less severe in terms of rights infringement than permanent ones (Bar-Siman-Tov, Reference Bar-Siman-Tov2018a). For example, in constitutional law, an important aspect of the proportionality principle is that any suspension of human rights should be temporary, and that such suspensions can only be justified in periods of emergency (McGarrity et al., Reference McGarrity, Gulati and Williams2012). When there is a need to limit civil liberties or human rights, temporary measures serve as a more proportional solution that causes less harm (Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Masur and McAdams2014; Bar-Siman-Tov, Reference Bar-Siman-Tov2018a).

Accordingly, temporary measures and sunset clauses are often proposed in times of emergency and turmoil. A prominent example of such chaotic circumstances is the context of terror attacks and the counterterrorism policies that follow. These circumstances may encourage the public to grant powers that threaten grave and permanent damage to human rights (Ackerman, Reference Ackerman2006).

Policymaking in response to the threat of terrorism has several characteristics that make the use of rights-restricting temporary measures especially common. Policymakers are often required to respond urgently to unexpected events under conditions of grave uncertainty, and their responses often have severe impacts in terms of human rights. Such circumstances frequently lead lawmakers to institute ad-hoc temporary policies. Indeed, the use of temporality in counterterrorism legislation is increasingly common. Examples of sunset clauses incorporated in counterterrorism legislation include the Patriot Act in the USA, the Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act in the UK, the Anti-Terrorism Act in Canada, the Prevention of Terrorism Act in India and the amendment to the Citizenship Law in Israel.

The rise in the use of temporary measures in the counterterrorism context and other domains has triggered a scholarly debate over the costs and benefits of this practice. In the following sections, we review the divergent views regarding the use of rights-restricting temporary measures in counterterrorism policy. Temporality can be considered from two perspectives: it can be viewed prospectively, in the sense that a policy is being considered for the first time and adopting it as a temporary measure is one of the options; or it can be considered retrospectively, when policy was enacted in the past as a temporary measure and its extension is currently being considered. We focus on both aspects: prospective duration (i.e., restriction of a newly proposed policy to a limited period of time) and its retrospective duration (i.e., the endpoint of temporary measures when the timeframe set for their implementation has expired), and their implications.

The effects of prospectively temporal measures in the context of counterterrorism

Prospectively temporal measures are often proposed in the context of urgent circumstances that call for a quick response. ‘Panic theory’ holds that policy responses to terrorism tend to be overreactions due to irrational assessment of risk or populist reactions to public sentiment; the resultant policies tend to be overly rights-restricting and plainly bad (Tushnet, Reference Tushnet2003; Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2003; Posner & Vermeule, Reference Posner and Vermeule2003; Gross, Reference Gross2006). Therefore, designing these policies as prospectively temporal measures expresses the notion that the extreme circumstances are exceptional, as well as recognition of the weaknesses inherent in the decision-making process under such conditions. Proponents of including sunset provisions in counterterrorism policy do indeed view them as potential safeguards against the dangers of overreaction and the infringement of human rights. Importantly, according to Finn (Reference Finn2010), constructing a policy in prospective terms can reassure those concerned by the measure, minimizing their objections and persuading them to support what they otherwise would have rejected, thus easing passage of the law.

Scholars do seem to agree that prospectively temporal measures are easier to pass (especially when they include much-debated restrictions of human rights). This may be the case for several reasons. First, legislators expect temporary policy to be re-evaluated when more time can be devoted to the process, or in light of additional information that will become available. Second, since policymakers are generally risk-averse, sunset clauses allow them to act in the face of crisis while shifting the accountability for the policy to a later time (Gersen, Reference Gersen2007; Finn, Reference Finn2010). Third, due to the perception of temporary measures as less restrictive of rights, temporary measures are frequently perceived as compromise tools; this softens objections and increases the chances of garnering agreement.

Indeed, in being more easily persuaded to approve prospectively temporal measures, policymakers might be affected by what Simonson (Reference Simonson1989) first described as the compromise effect. According to the compromise effect, an alternative is preferable when it represents a compromise or middle option (Simonson, Reference Simonson1989). Moreover, the preference for compromise may increase when the choice is harder to make (Novemsky et al., Reference Novemsky, Dhar, Schwarz and Simonson2007). In these cases, choosing a compromise option might be easier to justify, both internally and externally (Tetlock, Reference Tetlock1985; Curley et al., Reference Curley, Yates and Abrams1986). Policymakers might therefore prefer approving a policy temporarily as a compromise between the two extremes of either rejecting it completely or approving it permanently.

The effects of retrospectively temporal measures in the context of counterterrorism

As explained above, both proponents and opponents of temporary legislation seem to agree that temporary measures are more easily passed, especially in the context of counterterrorism. Prospective temporary measures allow for the adoption of measures that might not be acceptable under regular circumstances. However, scholars disagree on the effect of setting an expiration date for such measures. Proponents of sunset clauses hold that such legislation ensures the expiration of rights-restricting legislation and other harsh measures upon the end of the emergency period. Therefore, by limiting the period of validity of the measure in advance, the chances of disproportional limitations are minimized (Ackerman, Reference Ackerman2004).

Some people, however, are significantly more sceptical and even critical of the incorporation of sunset clauses in counterterrorism policy, claiming that they fail to deliver on their promise. According to opponents of sunset clauses, a temporary policy that has already been in place is often more likely to be reinstated for a longer period of time or even permanently when re-evaluated. According to what has been termed ‘ratchet theory’, legal changes, under certain conditions, are unidirectional and entrenched (Posner & Vermeule, 2004). Thus, even when policy responses to emergency circumstances are focused on the short term, they tend to have unwanted long-term post-emergency effects. This is because the demarcation between emergency and normalcy is typically more blurred than originally assumed, as well as due to a normalization process that leads to the ‘stickiness’ of the policy, often also causing a ‘spill-over’ of the policy to realms unrelated to terrorism (Gross, Reference Gross2006; Finn, Reference Finn2010). Thus, retrospective temporary duration (i.e., the pre-existence of legislation that is now about to expire) may lead to the extension and perpetuation of counterterrorism policies, as well as policies in other domains.

Insights from the cognitive psychology literature can offer another explanation for this possible effect of retrospective temporary duration on the ‘stickiness’ of sunset clauses: status quo bias. Status quo bias refers to the tendency of individuals to prefer the current state of affairs. Since humans tend to fear the unknown, the disadvantages of disengagement from an existing state are perceived as greater than the advantages (Kahneman et al., Reference Kahneman, Knetsch and Thaler1991). Therefore, status quo bias (Samuelson & Zeckhauser, Reference Samuelson and Zeckhauser1988) can be characterized as a cognitive error where one option is incorrectly judged to be better than another simply because it represents the status quo (Bostrom & Ord, Reference Bostrom and Ord2006). Accordingly, retrospective temporary duration may lead policymakers to approve and extend existing temporary provisions.

Indeed, both Finn (Reference Finn2010) and Ip (Reference Ip2013) have shown, in a series of case studies, that including sunset clauses in counterterrorism measures did not lead to the creation of and exposure to more information or bring about increased deliberation in the extension process; on the contrary, such measures were often extended without any further deliberation. When such policies were discontinued, it was often due to external political conditions not caused by the mechanism itself (see also the case study by Gersen (Reference Gersen2007), with similar findings).

If prospective temporary duration reduces objections to the policy at the outset and retrospective temporary duration increases the chances that the policy will be extended, sunset clauses are not only ineffective at adequately protecting rights, but also counterproductive. Berman (Reference Berman2013) terms this phenomenon the ‘sunset paradox’. It may also demonstrate what behavioural scientists call the ‘slippery slope’ effect. The slippery slope effect refers to a situation in which people gradually escalate their behaviour, ending up allowing outcomes they would not have agreed to otherwise. This phenomenon is frequently studied in terms of ethical behaviour. For instance, grossly unethical acts can be explained by a series of smaller infringements that increased over time, leading to increasingly severe unethical acts that people would otherwise have considered impermissible (e.g., Welsh et al., Reference Welsh, Ordóñez, Snyder and Christian2015).

In the case of temporary legislation in counterterrorism policy and other rights-restricting policies, a slippery slope effect may refer to the initial, perhaps begrudging approval of a prospectively temporal measure, followed by extension of the policy for longer and longer periods of time (eventually becoming permanent). The significant infringement by such extended legislation on fundamental human rights such as the rights to privacy and liberty and the freedoms of speech and association (McGarrity et al., Reference McGarrity, Gulati and Williams2012) raises concern that legislators might be less sensitive to such infringements if they are committed gradually over time, in the manner of a slippery slope process.

The experiments

Through our experiments, we conducted an empirical examination of the theoretical ‘sunset paradox’ model, or the ‘slippery slope’ effect of temporary legislation. To do so, we tested the effects of both prospectively and retrospectively temporal legislation on the willingness to first approve and then extend temporary measures involving human rights violations as part of counterterrorism legislation.

According to the legal scholarship described above, prospectively temporal measures can have the effect of bypassing decision-makers’ concerns and reservations regarding a rights-restricting means, thus facilitating the approval of a measure that otherwise might not have been approved. Therefore, our first hypothesis was that individuals are more likely to approve a rights-restricting measure if it is temporary rather than permanent.

H1: A prospectively temporal policy will receive higher approval rates than a permanent policy ex ante.

Additionally, according to previous theoretical and normative investigations, despite the temporal nature of sunset clauses, when the expiration date approaches, a measure has a greater chance of being renewed, leading to the sunset paradox and slippery slope effect of temporary measures. Therefore, our second hypothesis was that individuals are more likely to extend temporary measures (or make them permanent) than to approve new measures.

H2: A retrospectively temporal policy (i.e., a policy that has been in effect temporarily) is more likely to be approved (extended) than a new measure.

Overview of the experiments

We conducted a series of three survey-embedded experiments administered by a local survey agency – panel4all – and fielded between August and November 2016. Participants were registered for an online panel and were randomly drawn by the survey agency. The sample was close to representative of Jewish Israelis by age, gender, education and religious background.

Respondents were asked to answer an online questionnaire prepared by Israeli academic researchers. In each experiment, respondents were asked to approve or reject a rights-restricting policy proposal that would permit the use of physical means of interrogation in national security cases. Respondents read a passage describing a policyFootnote 2 that would allow the Israel Security Agency to use physical measures to extract information in anti-terror interrogations of Jewish Israeli citizens and were asked if the policy should be approved. The background described for the proposed policy was the increase in Jewish terrorist attacks in Israel over the past several years. The experimental design varied in terms of the duration of the proposed policy, the information provided regarding prior legislation and the ways in which the questions regarding the policy approval were phrased. In all experiments, respondents reported their political ideology by placing their socioeconomic and political views on a scale from political left (1) to political right (10).Footnote 3

All of the experiments examined H1 by testing whether willingness to approve temporary measures might be greater than willingness to approve permanent ones under various conditions. Additionally, Experiment 1 examined H2 by testing whether there is greater willingness to approve measures already in effect as compared to approving new measures.

Experiment 1: Prospective and retrospective temporary duration as means of increasing the approval rate of controversial measures

Experiment 1 examined the effect of defining a policy as temporary on the willingness to approve a new rights-restricting policy, as well as the willingness to extend such policy once it is already in place. A total of 1206 respondents (50.6% females, M age = 39.67 years, SD age = 14.19 years) participated in the experiment. In total, 45.8% of respondents placed themselves in the economic right wing and 64.7% of respondents placed themselves in the political right wing. The respondents read a passage describing a policy that would permit physical interrogation measures to extract information from suspects and were then asked if, in their opinion, such a policy should be approved.

The study was conducted to examine the influences of both prospective and retrospective temporary duration on willingness to approve a rights-restricting policy. To reach a more nuanced understanding of these questions, for exploratory purposes, Experiment 1 further examined whether various durations of prospective and retrospective temporary duration would change the policy approval rates (e.g., does a policy that has existed for 1 year yield higher approval rates than a policy that has existed for 6 months or vice versa?). Therefore, respondents were randomly assigned to 1 of 20 experimental conditions that varied both in terms of the duration of time that the proposed policy would last (5 levels varying from 6 months to permanently) and in terms of the duration of time the policy had already been in place (4 levels varying from a new policy to 5 years) (for a detailed description, see Supplementary Materials). If the policy was said to be already in place, no further information was provided regarding its effectiveness.

We expected respondents faced with a new policy to be less willing to approve the policy than those faced with an existing policy. To further examine the effects of temporality on those opposed to the policy (i.e., to see whether prospective temporary duration can act as a compromise alternative), respondents who stated that they would not approve the proposed policy were presented with a follow-up question: whether they would approve the policy if it were enacted for a shorter period (one level down relative to what they had previously been presented with). For example, if a participant did not approve the proposed policy as a temporary measure for the duration of 1 year, he or she was subsequently asked whether he or she would approve it for a period of 6 months. If the proposed time period was 6 months, respondents were not asked the follow-up question. Willingness to approve or extend the suggested policy served as the dependent variable in this experiment.

Results

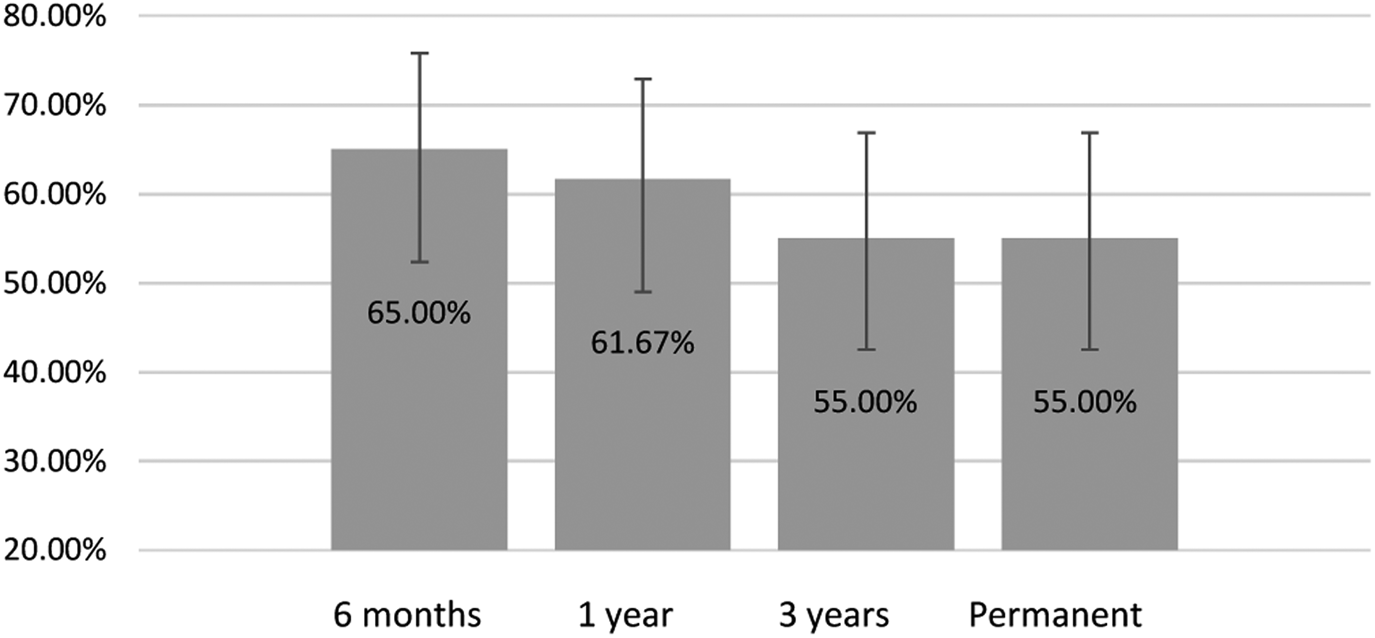

For prospective temporary duration, when asked to approve a new policy, 65% of respondents approved it for 6 months, 61.7% approved it for 1 year, 55% approved it for 3 years and 55% approved it permanently, indicating that the specific prospective durations did not affect approval rates (χ 2 (3, n = 240) = 1.86, p = 0.601). Importantly, when comparing all prospectively temporal policy durations to permanence, we do not find a significant difference in willingness to approve a new policy temporarily (60.2%) versus permanently (55.0%, χ 2 (1, n = 241) = 0.51, p = 0.48).

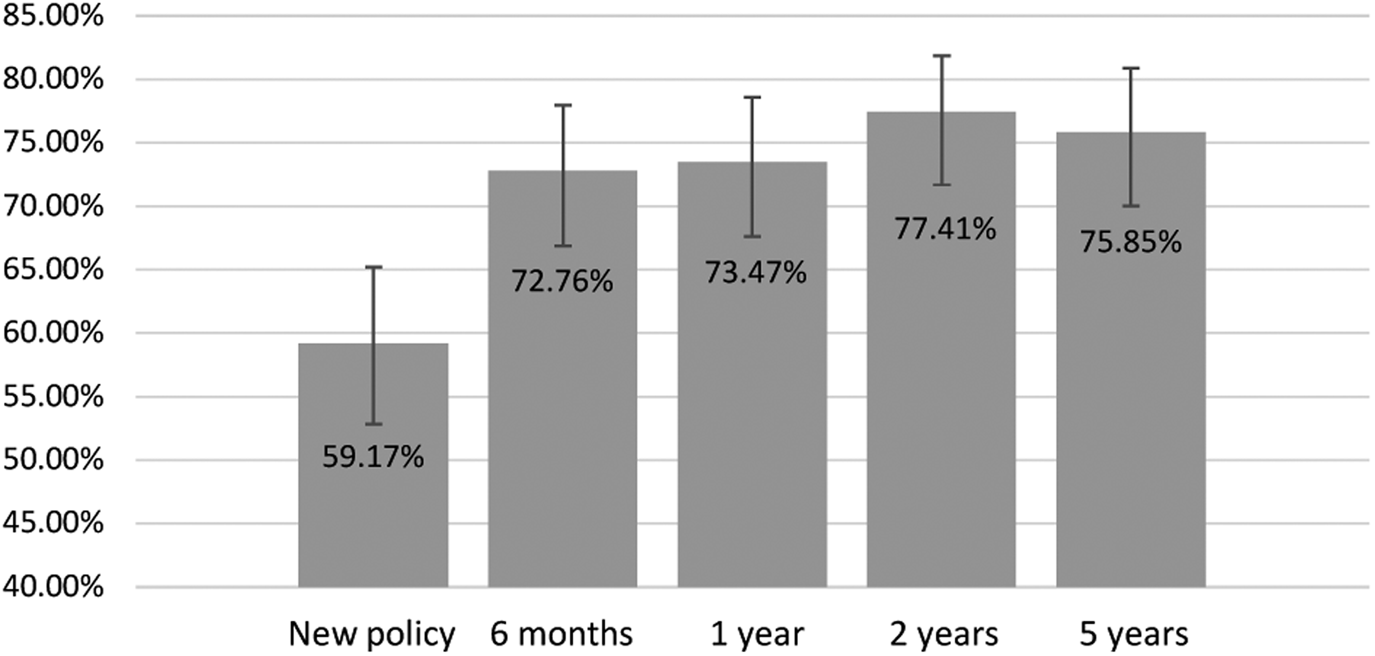

Next, we examined whether retrospective time variations – the length of time the policy was in effect in the past – affected respondents’ willingness to extend it. The results were 59.2% approval when the policy was new, 72.8% approval when it had been in effect for 6 months, 73.5% approval when it had been in effect for 1 year, 77.4% approval when it had been in effect for 2 years and 75.8% approval when it had been in effect for 5 years (χ 2 (4, n = 1206) = 24.94, p < 0.001, ϕC = 0.14). We find a significant difference in willingness to approve a policy that has been in effect for some time in the past (74.8%) as opposed to approving a new policy (59.2%, χ 2 (1, n = 1206) = 23.30, p < 0.001, ϕC = 0.14). However, there is no significant difference in approval ratings between the four retrospectively temporal durations (χ 2 (3, n = 966) = 1.77, p = 0.62). Importantly, as in the case of a new policy, in all cases where the policy had previously existed, there was no greater willingness to extend a policy temporarily (76.7%) than permanently (73.0%, χ 2 (1, n = 966) = 1.68, p = 0.20) (Figures 1 & 2).

Figure 1. Willingness to approve a newly suggested policy by prospective policy durations.

Figure 2. Willingness to approve the suggested policy by past durations.

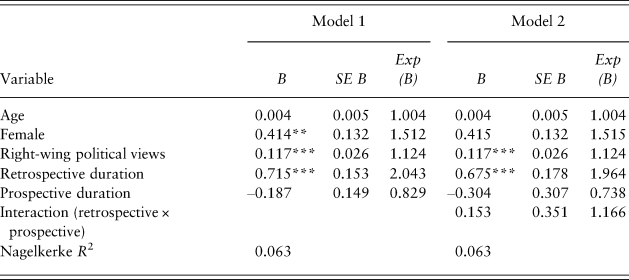

We conducted logistic regression analyses to predict willingness to approve the controversial measure based on its pre-existence and future duration, controlling for the following covariates: age, gender and political views. The results in Model 1 (Table 1) demonstrate that approval rates were shaped by retrospective temporary duration (b = 0.19, Wald χ 2 (1) = 16.3, p < 0.001), but not by prospective policy duration (b = –0.09, Wald χ 2 (1) = 2.44, p = 0.12).Footnote 4 Model 2 indicates no significant interaction between the two factors (b = 0.20, Wald χ 2 (1) = 0.81, p = 0.37).

Table 1. Willingness to approve the policy: hierarchical logistic regressions.

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

To examine non-linear effects, we conducted a second logistic regression with dummy variables for each pre-existing and proposed period (reference categories: new policy and permanent prospective duration). Regression results indicate a similar pattern (see Supplementary Materials Table 2).

Table 2. Willingness to approve the policy by suggested durations and experimental conditions.

Importantly, in response to the follow-up question for participants who did not approve the policy for the originally proposed period, 11.3% of these respondents subsequently agreed to approve the policy for a shorter period. This decision was not affected by the specific duration of the proposed policy (b = –0.165, Wald χ 2 (1) = 1.124, p = 0.29), nor by retrospective temporary duration (b = –0.055, Wald χ 2 (1) = 0.045, p = 0.95).

Discussion

The findings of Experiment 1 suggest that retrospective temporary duration results in greater willingness to approve a rights-restricting policy. Importantly, we found that any given timeframe of retrospective duration (from 6 months to 5 years) results in a similar increase in willingness to prolong the policy. These results suggest a status quo bias: once the policy was already in place (regardless of how long it had existed), respondents were less willing to change the status quo. These findings serve as preliminary evidence for a slippery slope effect, as past implementation of a policy may increase its chances of eventually becoming permanent. It may be the case that participants supported the extension of the temporary rights-restricting measures because the very suggestion of prolonging the existing measures implied that the measure had been found to be effective. Since no such information was provided, this may point to an additional problematic dynamic tied to temporary legislation: as Finn (Reference Finn2010) and Ip (Reference Ip2013) have indicated, rights-restricting temporary measures are often extended without exposure to new information or increased deliberation.

The results also show that participants were as likely to approve prospectively temporal measures as permanent ones. This does not support our first hypothesis that prospective temporary duration leads to greater willingness to approve a policy. This finding suggests that, without a reference point (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979), in the sense that participants are not aware of other possible durations and therefore do not compare the specific outcome to other possible outcomes, they are thus insensitive to variations in prospective durations of the policy.

However, we find that after having rejected the proposed policy in an earlier stage, some participants were willing to approve it for a shorter duration. This suggests that some individuals may be persuaded to approve a policy they would otherwise reject when offered a shorter temporary solution. Significantly, this required first introducing temporality with a longer duration. In other words, prospective temporary duration may have more impact in shaping willingness to approve restrictive measures when presented in the context of other possible durations. Our next experiments were designed to further examine whether prospective temporary duration shapes willingness to approve rights-restricting policies.

Experiment 2: Prospective temporary duration as a means of increasing the approval rate of controversial measures

In Experiment 1, we found that some of those who were unwilling to approve the policy when first exposed to it were willing to approve it for a shorter period. Experiment 2 was designed to further examine whether prospective temporary duration might promote compromise, resulting in greater willingness to approve a rights-restricting policy temporarily in comparison to permanently.

A total of 402 respondents (49.8% female, M age = 39.92 years, SD age = 14.18 years) participated in the experiment. In total, 51.5% of respondents placed themselves in the economic right wing and 61.9% of respondents placed themselves in the political right wing. As in the first experiment, respondents read a passage describing a policy proposal that would enable interrogators to use physical means to extract information from suspects posing a threat to national security. Respondents were randomly assigned to one of two experimental conditions. In the first condition (n = 210), respondents were asked whether they would approve the policy as a temporary measure for a period of 6 months. In the second condition (n = 192), respondents were first asked if the policy should be approved, without specifying the duration of the policy; this reflects permanent approval. As a follow-up question, respondents were asked whether they would be willing to approve the proposed policy as a temporary measure for a period of 6 months. We expected the approval rate for temporary measures following a suggestion to approve the measures unconditionally in Condition 2 to be higher than both the temporary approval in Condition 1 and the unconditional approval in Condition 2. Following the results of Experiment 1, we did not expect greater temporary approval in Condition 1 compared to the unconditional approval of the proposed policy in Condition 2 (as the temporary approval in Condition 1 was not put in the context of other time durations and therefore could not be perceived as a compromise).

Results

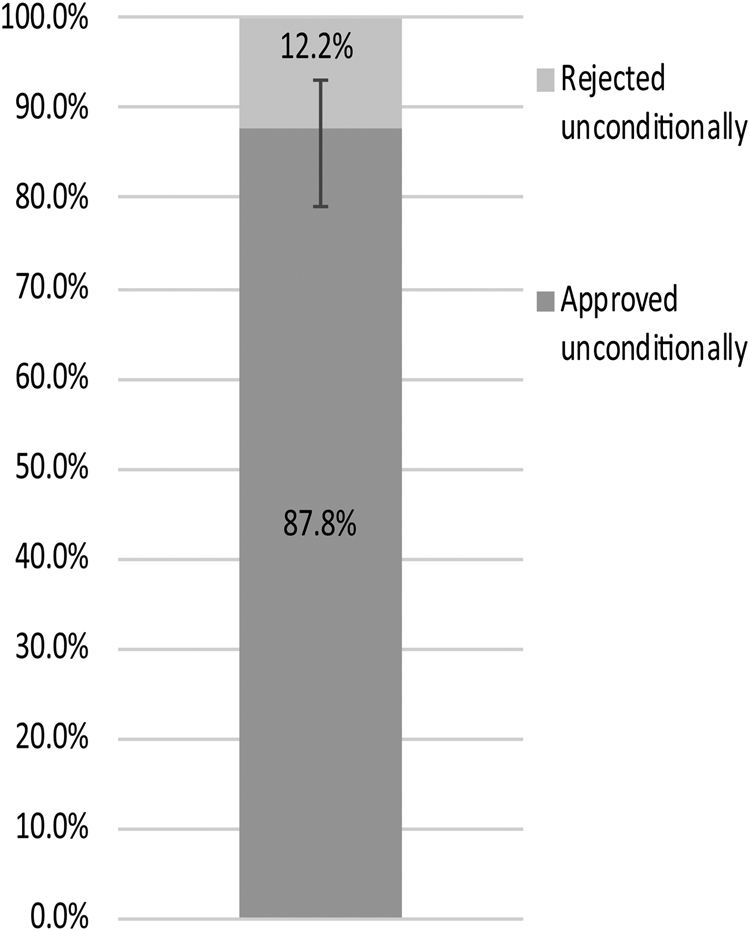

When asked if the policy should be approved temporarily for a period of 6 months, 53.3% of respondents agreed. When asked if the policy should be approved unconditionally (without any further information), a similar proportion of respondents (52.6%) agreed (χ 2 (1, n = 402) = 0.02, p = 0.89). When the question of temporary approval followed an unconditional approval (in the second experimental condition), the proportion of respondents who were willing to approve the measures dropped (43.2%; χ 2 (1, n = 400) = 4.14, p = 0.042, ϕC = –0.102) (see Figure 3 for the distribution of approval of the temporary policy between those who approved or disapproved the policy unconditionally). However, 11.2% of respondents who did not approve the measure unconditionally (Condition 2, n = 91) agreed to approve it temporarily.

Figure 3. Participants who approved the policy temporarily in Condition 2, divided according to their decision on whether to approve or reject it unconditionally in the previous step.

Discussion

Respondents presented with a serial evaluation (first being asked to approve a permanent policy and then being asked whether they would approve this policy temporarily) did not, overall, show greater willingness to approve the temporary measure. As in Experiment 1, the approval rates of respondents asked to approve a temporary policy did not differ from those of respondents asked to approve the policy unconditionally, ostensibly rejecting the hypothesis that prospective temporary duration leads to greater willingness to approve a policy. However, similarly to Experiment 1, more than 1 of every 10 respondents who originally rejected the permanent measure was subsequently willing to approve it as a temporary measure, probably because as a temporary measure it was perceived as more lenient and less restrictive. Although this proportion might seem relatively low, a shift in 11% of votes in favour of a controversial policy could easily prove crucial for the outcome. This finding supports the idea of a slippery slope effect among opponents of rights-restricting policies and demonstrates the concern expressed by scholars that temporary legislation might be used to sugar-coat rights-restricting policies (e.g., Finn, Reference Finn2009). Individuals who may find a rights-restricting policy unacceptable may be persuaded to approve the same policy temporarily.

Experiment 3: Prospective temporarily duration as a means of increasing approval rates of controversial measures – the effect of joint evaluation

In Experiment 1, we compared respondents’ willingness to approve a policy permanently or for various temporary durations, and each respondent separately evaluated the permanent and/or temporary policy duration. As participants were not aware of other possible durations, their sensitivity to prospective temporary durations (versus policy permanence) might have been reduced. However, when policymakers make decisions regarding a proposed policy, they often consider alternatives and evaluate the various options side by side. When policymakers evaluate several options and weigh temporary measures against permanent ones, they may prefer to approve the measures temporarily, since temporary measures are considered less severe (Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Masur and McAdams2014; Bar-Siman-Tov, Reference Bar-Siman-Tov2018a). Therefore, when presented with a choice between temporary and permanent measures, people are expected to be more willing to approve the temporary policy. In Experiment 3, we presented respondents with several possible prospective durations in a joint evaluation design in order to increase their awareness of alternatives and better simulate the policymaking process. For exploratory purposes, as in Experiment 1, we offered participants a choice between different variants of prospective temporary duration to examine whether this would play a role in determining approval rates.

A total of 395 respondents (54.2% female, M age = 38.9 years, SD age = 14.57 years) participated in the experiment. In total, 48.6% of respondents placed themselves in the economic right wing and 63.8% of respondents placed themselves in the political right wing. As in the previous experiments, respondents read a proposal for a rights-restricting policy that would permit the use of physical means of interrogation in national security cases. They were asked to indicate whether the proposal should be approved, and if so, for how long. The options were presented to respondents on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (rejecting the policy), through 3 levels of temporary durations (ranging from a short duration to a longer one), and finally to 5 (approving the policy permanently). The rate of willingness to approve the policy for each duration served as the dependent variable in this experiment.

The experiment included two between-subjects experimental conditions. In the first condition, the possible durations ranged from 6 months to permanent, while in the second condition, the possible durations ranged from 1 year to permanent. The purpose of this between-subjects design was to examine the extent to which decision-makers are sensitive to specific policy durations and whether variations in temporary durations affect their decisions.

Results

Despite the difference in durations associated with each scale point (i.e., 1–5) in the different conditions, we found similar approval rates of scale points between conditions (M = 1.10, SD = 1.46 and M = 1.31, SD = 1.45 for the first and second experimental conditions, respectively, t(393) = –1.50, p = 0.14).Footnote 5 However, we found a significant difference in willingness to approve the proposed policy for 1 year (12.6% in the first condition (scale beginning with 6 months) versus 32.5% in the second condition (scale beginning with 1 year), χ 2 (1, n = 395) = 22.32, p < 0.001) (Table 2). Since we found similar approval rates of scale categories across the two scales, these experimental conditions are combined in the findings reported below.

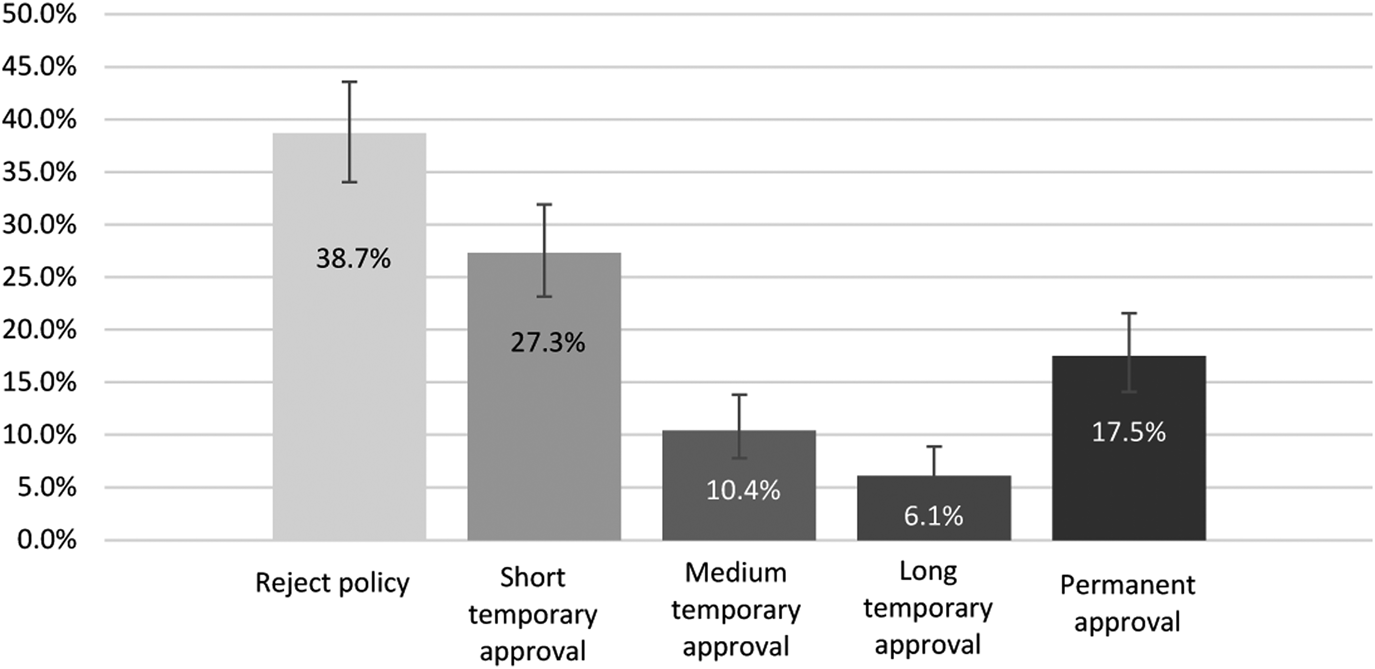

A larger proportion of participants chose to approve the policy for some prospectively temporal duration (43.8%) than approved it permanently (17.5%). Additionally, a larger proportion of participants were willing to approve the policy for a prospectively temporal period than rejected it (38.7%; see Figure 1). Among participants who chose to approve the policy temporarily, we found a clear preference for the shortest temporary duration (27.3% for the shortest temporary duration, 10.4% for the middle temporary duration and 6.1% for the longest temporary duration) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Willingness to approve prospective policy durations.

Discussion

Contrary to our findings in Experiment 1, we found that prospective temporary duration increased overall willingness to approve the policy when a choice was given between temporary or permanent approval and dismissal of the policy. It appears that the joint evaluation scale provided context that allowed participants to differentiate between permanent and temporary approval within the same question. This may have led participants to perceive temporary approval as more lenient and less restrictive of rights.

Additional support for this idea may be found in the clear preference of participants for the shortest temporary duration. The findings of Experiment 2 suggest that prospective temporary duration may act as a compromise between approving a rights-restricting policy permanently and rejecting it. Since Experiment 1 indicated that there is a greater chance of extending a temporary policy than of approving a new one, persuading policymakers to approve temporary measures that they would otherwise reject may lead to a dangerous slippery slope in terms of human rights infringement.

General discussion

This study is the first to undertake an experimental analysis of the behavioural implications of making rights-restricting temporary policy and its susceptibility to a slippery slope effect. Our findings show an increase in willingness to approve a rights-restricting policy proposal when the policy was already in place and about to expire, regardless of how long it had been in place, compared to approving a new policy. This supports the effect of status quo bias on increasing willingness to extend a temporary rights-restricting measure once it is already in place.

Regarding new policies, contrary to our expectations, we found no difference in approval rates between temporary and permanent policy proposals when the options were presented in isolation. However, some of the respondents who rejected the proposed policy as a permanent measure were subsequently willing to approve it temporarily, and some of those who rejected the policy for a specific period of time were willing to approve it for a shorter period of time. Furthermore, when presented with the options of adoption of a rights-restricting measure temporarily, permanent approval or complete rejection, the temporary options were most frequently selected. These findings demonstrate that temporary policies enjoy higher approval rates, but only when the temporary nature is emphasized, thus triggering a compromise effect between action and inaction. Needless to say, if the word ‘temporarily’ is used in a cynical and Machiavellian way, then such an approach might cause legal policymakers to make use this tool in ways that are harmful to the values being sacrificed for the particular public policy.

Taken together, our findings support the ‘sunset clause paradox’: they suggest that making temporary policy may lead, through a slippery slope, to the perpetuation of policy that may not have otherwise been approved. Thus, initially choosing a temporary design to help mitigate the rights infringement may ultimately facilitate graver infringement without the needed deliberation. These findings are consistent with the literature on the compromise effect (Simonson, Reference Simonson1989) and status quo bias (Samuelson & Zeckhauser, Reference Samuelson and Zeckhauser1988; Bostrom & Ord, Reference Bostrom and Ord2006). Our findings support the notion presented by Finn (Reference Finn2010) and Gersen (Reference Gersen2007) that including such clauses can act to reassure those concerned by the measure, minimizing their objections and persuading them to support what they otherwise would have rejected, thus making the policy easier to pass. Moreover, while proponents of including sunset clauses in counterterrorism measures believe that such clauses will minimize the chances of disproportional limitations persisting over time (Ackerman, Reference Ackerman2004), our findings provide experimental support for the claim put forth by Finn (Reference Finn2010) and Ip (Reference Ip2013), based on case studies, that measures originally adopted temporarily often end up being extended. Bar-Siman-Tov and Harari (Reference Bar-Siman-Tov and Harari-Heit2019) offer a review of ways through which temporary legislation might cause irreversible harm, especially when it is extended again and again.

Our study has several notable limitations. First, the participants in this study were laypeople, not professional decision-makers or legislators. Professional decision-makers have previously been found, in multiple studies, to be equally affected by psychological biases as laypersons (e.g., Landsman & Rakos, Reference Landsman and Rakos1994; Wissler et al., Reference Wissler, Hart and Saks1999; Sulitzeanu-Kenan et al., Reference Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Kremnitzer and Alon2016; Statman et al., Reference Statman, Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Mandel, Skerker and De Wijzeforthcoming). Nevertheless, future research should examine the effects of making temporary policy among professional policymakers as well.

Second, the study focuses on one policy scenario in one national setting. In Israel, the use of temporary measures has been relatively pervasive (Bar-Siman-Tov, Reference Bar-Siman-Tov2018a), mainly as a reaction to lasting security concerns – the product of long-lasting military tensions with neighbouring countries and with respect to residents of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip (e.g., Lapidoth & Friesel, Reference Lapidoth and Friesel2010). These unique circumstances might create differences in the initial approval rate of the suggested policy across countries. However, such differences would express themselves in the baseline results, not in the treatment effects. We therefore believe that the behavioural mechanism could be generalized to other circumstances. Furthermore, Israeli case studies have played a central role in other countries’ deliberations over the use of rights-restricting measures (e.g., Roznai, Reference Roznai2016). Nonetheless, future research should be conducted in additional national settings and should consider different scenarios that vary in terms of the policy goals and rights involved.

Considering that this paper presents the first experimental study of the effect of temporary legislation on the willingness to restrict human rights, one should be cautious in drawing conclusions from our findings. Nevertheless, one tentative implication for the debate over temporary rights-restricting legislation may be the importance of mechanisms that reinforce the temporary and experimental nature of the measures and the expiration date of the policy, so as to weaken the effect of status quo bias. One such mechanism might be requiring a larger majority to extend a temporary measure. Further research might look at whether the compromise effect that leads to greater support for temporary measures in the first place can be mitigated – for example, by emphasizing the likelihood of recurring extensions. Creating a mechanism that will make the extension process especially demanding, thereby helping policymakers to see the extension as a new rather than default move, might reduce the likelihood of an abuse of the important tool of temporary legislation. Requiring policymakers to create a whole new processes of legislation each time they only want to extend the temporary legislation might reduce the likelihood of instituting a temporary legislation in cases where the hidden motivation is to create a permanent legislation through the back door. In all other cases, where the motivation for temporary legislation is genuine and legitimate for reasons related to uncertainty and experimental legislation, the fact that the extension process will become more burdensome is less likely to have a chilling effect.

Further recommendations as to how temporary legislation should be designed to enhance its positive rather than negative behavioural and normative consequences would require further empirical work.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2020.35

Financial support

This study was conducted as part of the ‘Proportionality in Public Policy’ research project at the Israel Democracy Institute. It received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013), ERC Grant No. 324182.