In 1997, Daniel Kahneman, with his co-authors Peter Wakker and Rakesh Sarin, wrote the manifesto-like paper ‘Back to Bentham: explorations of experienced utility’ (Kahneman et al., Reference Kahneman, Wakker and Sarin1997). In it, they laid out a hedonic view of utility that promised to go some way back to what might be called ‘personal utilitarianism,’ according to which the quality of life can be evaluated by measuring the momentary well-being a person is experiencing and then integrating those measurements over time. They spoke of ‘temporally extended outcomes’ (TEOs), meaning slices of life for which well-being could be measured separately, and discussed how these measures of well-being could be aggregated (or ‘concatenated’), so that the goodness of the whole life could be treated as the sum of the well-being from all of its TEOs. This paper, in conjunction with a series of other important works, significantly influenced the now vast field of ‘happiness studies’ (Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2022) and continues to be a major empirical and conceptual touchstone in economic philosophy and behavioural public policy (Hausman, Reference Hausman2010; Layard, Reference Layard2010; de Lazari-Radek and Singer, Reference de Lazari-Radek and Singer2014; Oliver, Reference Oliver2017; Fryxell, Reference Fryxell2024).

My discussion will take as its starting point a key passage from Kahneman et al. (Reference Kahneman, Wakker and Sarin1997). My mind has returned repeatedly to this passage since I first began to seriously consider the question of ‘what’ utility is (Read, Reference Read2006, Reference Read2007).

Our normative treatment of the utility of temporally extended outcomes adopts a hedonic interpretation of utility, but no endorsement of Bentham’s view of pleasure and pain as sovereign masters of human action is intended. Our analysis applies to situations in which a separate value judgement designates experienced utility as a relevant criterion for evaluating outcomes. This set does not include all human outcomes, but it is certainly not empty. (Kahneman et al., Reference Kahneman, Wakker and Sarin1997, p. 377)

This is an unsettling passage to find in a paper entitled ‘Back to Bentham’. Bentham had no such qualms and this ‘separate value judgement’ was the cornerstone of his philosophy, whereas Kahneman makes it optional. It appears there are higher-level principles that determine what is best for us other than only pleasure and pain. If so, what makes the set ‘not empty?’ In this paper, I will briefly describe the Benthamite and the Kahnemanian approaches and then report some preliminary thoughts about what the ‘separate value judgement’ (or judgements) may be. My focus will almost exclusively be on the 1997 paper, and it should be understood that Kahneman’s thoughts on this matter varied and evolved. My own thinking evolved while writing this paper, and what I believe now is not what I expected to believe when I started typing. It is a matter of considerable regret that I did not personally ask for Kahneman’s thoughts on this issue when I had the opportunity.

Back to Bentham

Although Bentham did not name his method, subsequent writers described his quantitative approach using such terms as ‘the felicific calculus’ (from Mitchell, Reference Mitchell1918) or ‘the hedonical calculus’ (from Edgeworth, Reference Edgeworth1881). While Bentham is associated with utilitarianism (a term he did not himself use) which proposes as its moral goal the ‘greatest happiness for the greatest number’, much of what I will say concerns what philosophers call hedonistic egoism, or ‘the greatest happiness for the individual’. As sources, Bentham (Reference Bentham1789) and the extensive excerpts in Halévy (Reference Halévy1995) are most relevant.

According to this variant of egoism, the goodness of an act is determined by the pleasure it produces or the pain it avoids for the acting individual. Pleasure and pain come in units, which are ‘just noticeable’ increments or decrements to happiness, spanning a minimum duration (call this a moment). During an extended period, the total pleasure experienced by an individual is the number of such units they experience in all the moments spanning that period. The total utility from a whole life can be measured as this sum taken over that life.

Bentham recognised that pleasures and pains take many forms that are not obviously alike. He was, indeed, almost uniquely attuned to this fact and conducted a scrupulous inventory. He identified 14 simple sources of pleasure (e.g., the pleasures of sense, wealth, amity, malevolence and piety) and 13 simple sources of pain (e.g., the pains of sense, privation, enmity, malevolence and piety) – most sources of pleasure had a corresponding source of pain. The ‘simple’ pleasures of piety were described as follows:

The pleasures of piety are the pleasures that accompany the belief of a man’s being in the acquisition or in possession of the goodwill or favour of the Supreme Being: and as a fruit of it, of his being in a way of enjoying pleasures to be received by God’s special appointment, either in this life, or in a life to come. (Bentham, Reference Bentham1789, 59)

The pains of piety come from being in God’s bad books. All pleasures and pains were ultimately commensurable, enabling the total pleasure and pain to be measured when even the most seemingly disparate influences are simultaneously in operation. It is also evident that these pleasures and pains could be quite complex and sophisticated – piety will not give rise to the same kind of pleasurable sensation as will food or vigorous exercise.Footnote 1

Utilitarian philosophers viewed the choices people made as a direct index of the pleasure and pain that would arise from an action. Bentham, in particular, argued that money could be used to measure utility even in the absence of a market:

If then between two pleasures the one produced by the possession of money, the other not, a man had as leif enjoy the one as the other, such pleasures are to be reputed equal. (Quoted in Halévy, Reference Halévy1995, p. 207).

For Kahneman et al. (Reference Kahneman, Wakker and Sarin1997), a crucial distinction is between decision and experienced utility. Decision utility is the utility or value that can be inferred from the choices people make; experienced utility is the experience of that choice. As is evident from this passage, Bentham did not see these as being different, but Kahneman did. He argued, backed up by ingenious experiments, that people often choose that which is not the best for them in experience. This faith in individual decisions is a key distinction between Bentham (and as far as I can tell, all the classic utilitarians) and Kahneman.

The temporally extended outcome

The TEO is a unit or slice of life comprising experiences that make up, perhaps loosely, an identifiable psychological event. As examples, Kahneman et al. (Reference Kahneman, Wakker and Sarin1997) referred to ‘a single medical procedure [such as a colonoscopy] or the concatenation of a Kenya safari and subsequent episodes of slide-showing and storytelling’ (p. 376). Clearly the category of TEO is fuzzy, with the endpoints of any TEO being themselves matters of judgement.

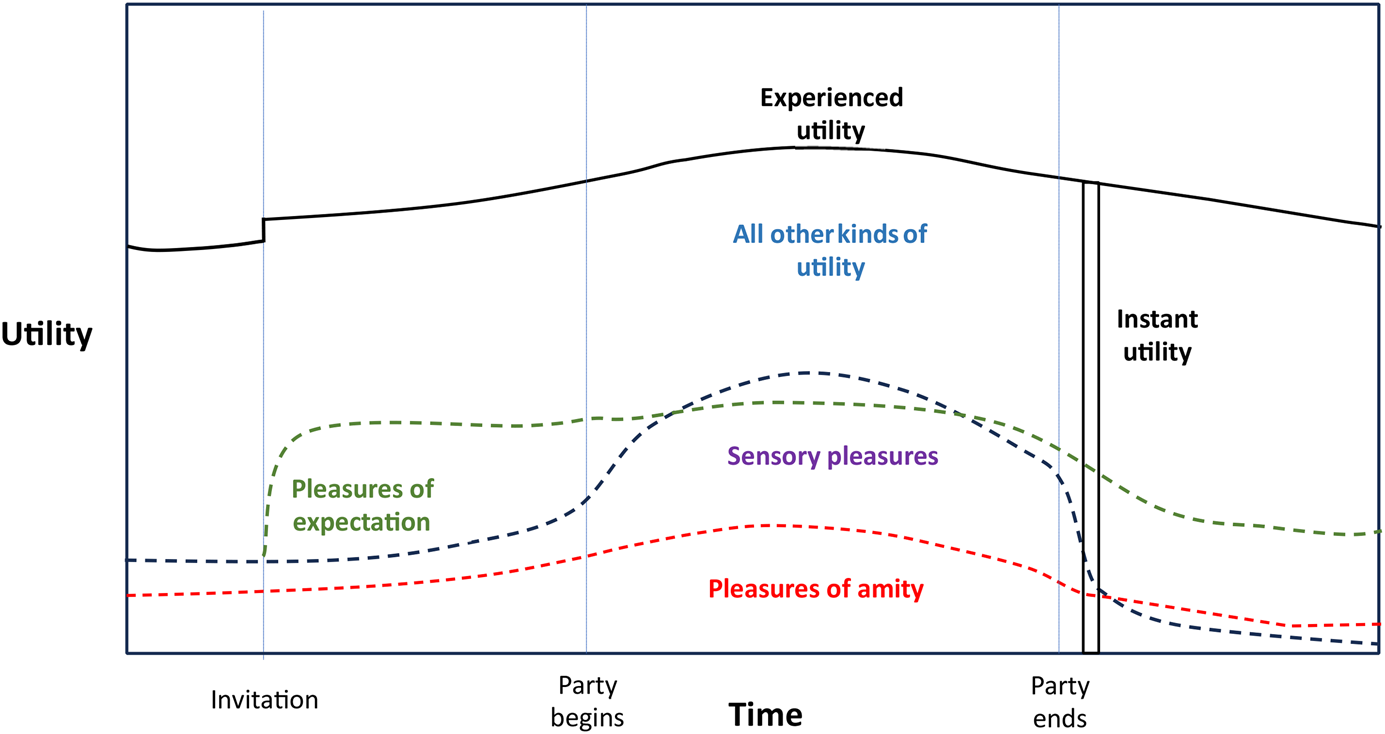

How do we describe the utility experienced during or derived from a TEO? We can take two analytic approaches, each having Benthamite roots. Both begin with instant utility, a measure taken at a single moment of the current degree of pleasure or pain. In the first approach, we consider what choices or experiences have an influence at each moment and describe the stream of utility as the sum of the separate pleasure and pain contributions of all those experiences. In the second approach, we consider the kinds of pleasures and pains (such as those described by Bentham) contributing to experience at any moment and describe the stream of utility as reflecting the relative contribution of each kind. Regardless of the approach, we can sum over the period to determine ‘total utility’ for that period. Instant utility at each moment and total utility over the entire TEO are unaffected. Both ways are shown in Figure 1, illustrating the same period of time.

Figure 1. Utility of a single event (a party) and its relationship to instant and total utility over a selected period of time.

Note: The black line at the top indicates experienced utility. The height of the line at any point is instant utility at that point, and the area under the black line is total experienced utility. The red dotted line is the part of experienced utility attributable to the party.

Imagine you have been invited to a party. Receiving the invitation is exciting in itself and this leads to a positive shock in the level of your experienced utility. You eagerly look forward to the party, have a great time while it is taking place and then recall it fondly once your hangover dissipates. These positive recollections continue, although after a while they will play only a small residual role in experience. Figure 1 shows the instant utility at every point, and that which is attributable to the party is shown as a red dashed line.

Utility at any moment during this period is directly measurable, as it is happening, usually in the form of instantaneous self-report.Footnote 2 Self-report is, however, neither necessary nor sufficient. Physiological measures of instant utility might be available instead of self-report (Berridge and O’Doherty, Reference Berridge, O’Doherty, Glimcher and Fehr2014), and it is conceivable that self-report, even if honest and even if the question being asked is well formulated, might not effectively capture all aspects of instant utility. Utility might not be conscious, although the utilitarian philosophers placed a great weight on the primacy of consciousness. Even Edgeworth (Reference Edgeworth1881), in his famous account of the hedonistic calculus, insisted that his idealised system would measure well-being ‘exactly according to the verdict of consciousness’.

Crucial to measuring experienced utility is that, at any moment, we do not need to measure how much instant utility is attributable to a specific action, nor the actions that are contributing to that instant utility, but only the level of instant utility at any moment. In the example, even when the party is actually taking place, it will not be the only determinant of instant utility. You will likely be somewhat happier when the party is taking place than when it is not, and overall the party increases your average happiness (or reduces your average pain) while you are anticipating it and remembering it. Figure 1 shows how instant utility is partly determined by what we can call the focal outcome (the party) and partly determined by other factors. During the party, for instance, you might be thinking about the new puppy that will be arriving tomorrow, or a research idea that you cannot get out of your head, or worried about the pending results of a medical procedure.

There will be situations in which a focal outcome will be disproportionately important, and in some circumstances, it may be all absorbing while it is taking place.

The colonoscopies which Kahneman studied, for example, were likely the primary source of instant utility for patients while they were taking place (Kahneman et al., Reference Kahneman, Fredrickson, Schreiber and Redelmeier1993). Similarly, many researchers have put forward concepts such as ‘flow’ to describe the experience of being so absorbed by a positive task that nothing else enters the mind. Kahneman (Reference Kahneman2011, p. 200) took the view that the focal experience was of paramount importance: ‘Our emotional state is largely determined by what we attend to, and we are normally focused on our current activity and immediate environment’.

Figure 2 shows another way of analysing the same TEO into the determinants of utility or value, which are drawn from Bentham’s (Reference Bentham1789) list. Only some of these determinants are given. Both figures are greatly simplified, since at any moment all of one’s previous life choices will have an effect (albeit small) on current activities, and even future activities that are currently being planned or considered will have an effect in terms of anticipation. In theory, it is possible to analyse instant utility into all of its experiences and their determinants, and see in each instant utility cross-section how much each determinant is contributing to the utility contribution of each experience. In practice, this is unlikely to ever be done.

Figure 2. Kinds of utility and their relationship to instant and total utility over a selected period of time.

The interrupted record

In his TED talk, Kahneman (Reference Kahneman2010) reported how one reader of his book reported that he had been listening to an exquisite recording of a symphony when the entire experience was ruined by a terrible screeching sound at the very end. The anecdote of the interrupted recording is used to distinguish between the experiencing self and the remembering self. Kahneman argued that the listener was wrong about the experience, which was largely unaffected since the screeching sound came in the final movement. It was his memory of the performance that was ruined.

Kahneman proposes that for a given experience, we can divide a person into an experiencing self and a remembering self. Concerning the same moment, these will be different selves. There are two forms of utility due to memory. One form is ‘remembered utility’. It is the retrospective judgement of the quantity of utility experienced over a TEO. A question like ‘taking everything into account, what was the symphony like?’ would be one way of measuring remembered utility. If decision utility is based on predicted utility, then the choice to re-experience one future TEO over another, as in the colonoscopy experiments, would be another way of measuring the same thing. Remembered utility, in this sense, has no affective content. Memory is a yardstick.

But memory does not restrict itself to measurement. Episodic memory enables us to re-experience the event and interpret it and discuss it. These recollections are themselves sources of utility. Kahneman et al. (Reference Kahneman, Wakker and Sarin1997) discussed these when they referred to the ‘subsequent episodes of slide showing and storytelling’ after a trip to Kenya.

The slide showings are why the TEO does not end when you check out of the hotel. And the disappointed music lover will continue to relive their disappointment. In some cases, perhaps as in this one, this remembering utility from bad experiences will be positive. That of good experiences can also be negative.

Moreover, memory is not only episodic. Every experience transforms us in multiple ways, some small and some large.Footnote 3 The unfortunate listener might flinch from further recordings of that symphony or be more careful with his vinyl collection in the future. Such effects need not be conscious, but they are all part of remembering utility, or the utility that arises when recalling an event. This is why, in Figure 1, the instant utility attributable to the party does not go to zero and, in fact, never will.

We not only have to concern ourselves about the remembering self, but also about the anticipating self, who begins to accumulate instant utility from knowing what future events might occur (again as in Figure 1). The anticipating self is also an experiencing self. Memory and anticipation are part of the experience. While it is interesting to consider how the various kinds of experience differ, it is also important to recognise that if all we are concerned about is experiencing utility, the details of when an event occurs – that is, whether it is nominally occurring at the moment of measurement, has occurred in the past or will occur in the future – do not matter.

The separate value judgement

The ‘separate value judgement’ is needed to decide whether the total utility measured during a TEO is ‘a relevant criterion for evaluating outcomes’. In one sense, it will almost always be relevant, if by relevant we mean that it is one thing worth considering when assessing an outcome. But this does not seem ambitious enough nor, to be honest, very useful. Let’s assume that what is intended is that there are at least some TEOs for which we can measure total utility, and when we do so we have measured what is normatively important about the TEO and can therefore identify whether one TEO is better, worse or equivalent to another. This then enables us to say that people have made a mistake if they choose one that is not the best.

Two possible value judgements are what we can call comprehensiveness and personal independence.

Comprehensiveness

A comprehensive measure of utility captures all relevant aspects of instant utility (the cross-section of Figures 1 and 2) in a single measure. Kahneman et al. (Reference Kahneman, Wakker and Sarin1997) proposed that whereas previous economists believed it was impossible to measure subjective experience (including instant or experienced utility), psychologists and present-day economists know better. Comprehensiveness is, therefore, a candidate separate value judgement: Is the measure missing part of the cross-section? If so, the purported total utility is not the total utility. The major threat here is that the measurement we take might be some subset of experience on which attention is focused. As Kahneman said, ‘what you see is all there is’. If we ask someone how happy they are at a party, they might tell us about the happiness they experience due to the party, but not their overall level of happiness at that moment.

Another aspect of comprehensiveness is that any measuring instrument we use might not capture what is going on in all occasions. Scholars with a utilitarian inclination might wish to assume all pleasures and pains are associated with the same feelings with, ideally, pleasure being the mirror image of the pain experience and measurable on the same scale. Edgeworth’s (Reference Edgeworth1881) hedonometer certainly has this flavour. But this is likely incorrect, since there may not be a single characteristic of experience that is associated with all pleasure. If we go back to Bentham, it is not likely that he believed the pleasures of piety are identical in kind to ‘the pleasures of the sexual sense’, yet they are both in his view commensurable. We need not doubt this is true even if we doubt the commensuration is done by any instrument currently in use. The colonoscopy studies are illustrative. Participants rated their pain on a 100-point scale. Were they only feeling pain, or perhaps also fear and hope and even curiousity? If so, did the 100-point scale capture it all?

Personal independence

As discussed already, a single slice of life (the TEO), measured while it is occurring, may not capture all the consequences for that person of all the activities undertaken during that period, even if the measure we have taken is comprehensive for that period. We can use the term personal independence to denote a situation in which a TEO is, according to any reasonable judgement, fully independent of other TEOs with which it might be concatenated. For instance, the colonoscopy experience would be personally independent if it could be slotted into a life while changing no other TEO in that life. One separate value judgement that needs to be made is that the specific TEO we are looking at displays personal independence from other TEOs with which it will be concatenated. Alternatively, the specific TEO would contribute the same quantity of total utility to any life.

Such TEOs may not be easy to identify. True, they may be created by expanding the time horizon over which measurement is made, potentially increasing the chance that all interactions are accommodated within the TEO. Expanding the time, however, may always leave a ‘fringe’ of effects outside of the TEO, unless the entire life is embraced within the single TEO. Concerning this, it is worth remarking that Edgeworth (Reference Edgeworth1881, p. 101) included in his description of the hedonometer the requirement that the ‘integration must be extended from the present to the infinitely future time’.

Appropriate TEOs may also be created by selecting events that are truly irrelevant or ‘swappable’ with other events. So far, I have not been able to think of any such cases. Certainly not painful colonoscopies.Footnote 4 Perhaps, in all practical circumstances, no TEO can be arbitrarily combined with other TEOs. Rather, the TEOs to be combined must come from the same life and, indeed, the impact of a given action cannot be fully captured without combining all the TEOs of that same life, and consequently, we still have to go ‘back to Edgeworth’.

Other separate value judgements

These may be the main value judgements but there are others. One possibility is that instant utility, even if the measurement is comprehensive and personal independence is maintained, might not capture all that matters. We can consider, as an objection, the ‘van Gogh example’. Vincent van Gogh (at least the van Gogh of myth) struggled his entire life to master his craft yet received no reward for doing so. If we measured van Gogh’s instant utility over his life, it might well have been worse than people whose lives are distinctly unremarkable. If van Gogh had a choice, however, he might have preferred his life of struggle to an unremarkable but happy one. Perhaps, no measure of pleasure and pain that we would take over Van Gogh’s life, regardless of how precise that measure is, might make his life preferable to the unremarkable one.

A further value judgement may be that the utility of the TEO should be sufficiently independent of the utility of other people, meaning it should have no externality or at least not one that matters. If a TEO draws its utility at the expense of others, or benefits others, then this particular ‘separate judgement’ may not be made. The TEO of a profiteer in the process of gaining personal benefit at the expense of others would perhaps not meet the criterion for the separate value judgement. Nor would the TEO of a hero or martyr who sacrifices their well-being for the benefit of others. For Bentham and other utilitarians, this issue was central to their project, although it is not clear that this is of vital importance for modern economics.

Conclusions

Kahneman’s early work in experienced utility was based on an approach that he had successfully applied in some of his greatest work. This was to scrutinise how people make judgements about a quantity and to learn the relationship between the information people had about that quantity and these judgements. Kahneman and Tversky learned that people use simplifying rules, such as the availability and representativeness heuristics, that, while in most cases are very effective, can nonetheless go wrong (see, for example, Kahneman (Reference Kahneman2011)). In the work on experienced utility, the quantity was a measure of aggregate pleasure or pain over an interval, and the judgements were memories of that pleasure or pain or related decisions, such as whether to undergo the episode again. These judgements proved to be systematically biased in a manner quite similar to that found in the earlier work. Certain hard to evaluate information such as the duration of the experience was ignored, and easier to evaluate information such as the ‘peak’ and ‘end’ of the experience became the primary determinants of remembered utility. This also apparently led people to make poor decisions when decision quality was defined in terms of choosing the outcome that would lead to a better overall experience.

The experienced utility studies pose a challenge not faced by the heuristics and biases work. This challenge arises for exactly the reason Kahneman proposed: to say that option A is better than option B, and therefore, that the judgement of remembered utility is biased, requires a ‘separate value judgement’ about the relative merits of A and B. In this paper, I scrutinised this separate value judgement and reached a provisional conclusion that there may yet be few circumstances where we can make it with any confidence, except with respect to an entire life, and with respect to measurement procedures we do not yet have available. If this conclusion is correct, then the application of experienced utility is reduced since the set of relevant cases may actually be empty or at least very small. Or, alternatively, we are still in search of a different normative standard for choice.

Behavioural scientists have a great need for an unambiguous and measurable operationalisation of what is commonly called ‘utility’. The concepts and theoretical framework that Kahneman and his co-authors provided are foundational for achieving this operationalisation. Kahneman proposed, in essence, that we could go back to Bentham for a model of what we want to do, and look ahead to modern psychology and neuroscience for a model of how to do it. As with all attempts to define what is good in life, however, several questions are left unanswered. Some of these questions were sketched out in this paper and no doubt many remain.

Author contribution

Much gratitude is due to Despoina Alempaki and Caspar Kaiser for careful and insightful comments and to Thomas Hills for some robust objections. All greatly improved the paper.