Introduction

Multi-dimensional measures of perfectionism (FMPS; Frost et al., Reference Frost, Marten, Lahart and Rosenblate1990; HMPS; Hewitt and Flett, Reference Hewitt and Flett1991) have been found to consistently load onto two factors: perfectionistic strivings (rigid pursuit of perfectionism) and perfectionistic concerns (concerns over mistakes and other people’s judgement about performance) (Bieling et al., Reference Bieling, Israeli and Antony2004). Perfectionism has been proposed as a transdiagnostic process that pre-disposes and maintains depression, anxiety and eating disorders (Egan et al., Reference Egan, Wade and Shafran2011), supported by meta-analytic evidence (Limburg et al., Reference Limburg, Watson, Hagger and Egan2017). A transdiagnostic process is defined as one which is not specific to a particular psychological disorder, but operates across diagnostic boundaries (Dalgleish et al., Reference Dalgleish, Black, Johnston and Bevan2020). Despite consistent evidence from quantitative studies in adults for perfectionism as a transdiagnostic process associated with anxiety and depression, no studies to date have performed a synthesis of qualitative literature in perfectionism with a focus on young people. It is important to understand the role of transdiagnostic processes, such as perfectionism, and the perspectives of young people in order to inform early intervention for anxiety and depression (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Knight, Patel, So, Dunning, Barnhofer, Smith, Kukyen, Ford and Dalgleish2021).

The efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy for perfectionism

Clinical perfectionism is defined as self-worth based on striving to achieve high standards despite adverse consequences (Shafran et al., Reference Shafran, Cooper and Fairburn2002). Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for perfectionism (see Egan et al., Reference Egan, Wade, Shafran and Antony2014; Shafran et al., Reference Shafran, Egan and Wade2018) addresses the maintaining processes (i.e. factors that keep perfectionism going), outlined in the cognitive behavioural model of clinical perfectionism (Shafran et al., Reference Shafran, Cooper and Fairburn2002). CBT for perfectionism has been demonstrated to result in significant moderate between-group differences to comparison conditions in perfectionism (perfectionistic strivings, g = 0.48; perfectionistic concerns, g = 0.55), depression (g = 0.62) and anxiety (g = .49) (Suh et al., Reference Suh, Sohn, Kim and Lee2019). An earlier meta-analysis that also included open trials also demonstrated efficacy for CBT for perfectionism with large within-group effect sizes for perfectionism (e.g. perfectionistic strivings g = 0.79; perfectionistic concerns g = 1.32), but medium effects for anxiety (g = 0.52) and depression (g = 0.64) (Lloyd et al., Reference Lloyd, Schmidt, Khondoker and Tchanturia2015). This result was replicated in a subset of intervention studies that included disordered eating (Robinson and Wade, Reference Robinson and Wade2020), for both between- and within-group effect sizes. This raises the question of whether CBT for perfectionism has less impact on anxiety and depression than perfectionism, and if the treatment could be made more effective. Furthermore, while there is some evidence for the efficacy of CBT for perfectionism in young people (e.g. Shu et al., Reference Shu, Watson, Anderson, Wade, Kane and Egan2019), most studies have focused on adults. One way that the treatment development could be informed in young people is to consider qualitative studies.

The value of qualitative studies and meta-synthesis

Qualitative studies are vital to the in-depth understanding of concepts, relationships and experiences (Fossey et al., Reference Fossey, Harvey, McDermott and Davidson2002) that can inform treatment development. Qualitative studies are important to consider in perfectionism as they can assist in understanding the impact of perfectionism from a young person’s perspective, and how perfectionism is associated with anxiety and depression. There have been a number of qualitative studies of perfectionism in high school and University students (e.g. Ashby et al., Reference Ashby, Slaney, Noble, Gnilka and Rice2012; Neumeister, Reference Neumeister2004a; Neumeister, Reference Neumeister2004b; Neumeister, Reference Neumeister2004c; Neumeister, Reference Neumeister, Williams and Cross2007), and high performing athletes and musicians (e.g. Hill et al., Reference Hill, Witcher, Gotwals and Leyland2015). Two qualitative studies in adults found themes supporting the model of clinical perfectionism (Shafran et al., Reference Shafran, Cooper and Fairburn2002), including continual striving to meet high standards despite negative effects, reacting with self-criticism to failure (Riley and Shafran, Reference Riley and Shafran2005), and re-setting standards higher following both success and failure (Egan et al., Reference Egan, Piek, Dyck, Rees and Hagger2013). Other qualitative studies have reported positive feedback from participants after CBT for perfectionism (Larsson et al., Reference Larsson, Lloyd, Westwood and Tchanturia2018, Rozental et al., Reference Rozental, Kothari, Wade, Egan, Andersson, Carlbring and Shafran2020).

Despite a number of qualitative studies examining perfectionism, there have been no meta-syntheses of qualitative literature to date. Meta-synthesis involves a synthesis of a number of qualitative studies by translating findings into thematic statements, and building themes and categories that go beyond the original qualitative studies (i.e. meta-summaries) (Ludvigsen et al., 2015). Advantages of meta-synthesis are managing the amount of information that is generated across qualitative studies and stimulating debate (Ludvigsen et al., 2015). The authors performing the meta-synthesis are viewed as ‘third-order interpreters’ of the participants’ experiences (‘first-order interpreters’) and qualitative study authors views (‘second-order interpreters’) (Ludvigsen et al., 2015). A meta-synthesis of the link between perfectionism, anxiety and depression in qualitative study may be helpful to inform understanding and treatment of perfectionism, particularly in young people where few studies have examined CBT for perfectionism.

Why young people are important to consider in a review of perfectionism

It is well recognised that anxiety and depression typically onset in young people, and the onset of depression in adolescence has a robust and lasting association with adult functioning (Copeland et al., Reference Copeland, Alaie, Jonsson and Shanahan2021). Despite this, the views of adolescents and young people are often under-represented in research (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Knight, Patel, So, Dunning, Barnhofer, Smith, Kukyen, Ford and Dalgleish2021). Given recent meta-analytic evidence that perfectionism is increasing over time (Curran and Hill, Reference Curran and Hill2019), it is important to consider how young people view the role of perfectionism with respect to anxiety and depression in order to improve treatment. The vast majority of studies of treatment of perfectionism, however, have been conducted in adults, therefore understanding the views of young people from qualitative research may help inform future treatment approaches.

Aims of the present study

The aims of this review were to conduct a systematic meta-synthesis of qualitative research on perfectionism in order to: (i) help inform our understanding of how perfectionism is associated with negative affect, so that we can (ii) inform future development of treatment for perfectionism in young people, to improve efficacy.

Method

Literature search and study selection

The study protocol was registered on PROSPERO (Shamseer et al., Reference Shamseer, Moher, Clarke, Ghersi, Liberati, Petticrew and Stewart2015) in June 2020 (approval number CRD42020189170). A literature search was conducted by the primary reviewer (G.F.) in July 2020 across six electronic databases: PubMed/Medline, PsycINFO, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Embase, Web of Science and ProQuest Education Database. Inclusion criteria were (1) qualitative study and (2) investigation of perfectionism and depression and/or anxiety. Search terms were decided by the senior authors (S.E., T.W., R.S.), and included an extensive range of terms in order to capture experiences of anxiety and depression as widely as possible. The base keywords and Boolean operators used in the search included: Perfection* AND anxiety OR depression OR stress OR wellbeing OR well-being OR ‘mental health’ OR psychopathology OR ‘obsessive-compulsive’ OR ‘obsessive compulsive’ OR trauma OR ‘post-traumatic stress’ OR ‘posttraumatic stress’ OR ‘psychological disorder’ OR panic OR ‘specific phobia’ OR psychiatr*. To ensure a comprehensive search, a supplementary search was conducted on PsycINFO using the search terms: perfectionism AND qualitative. Age was not restricted in the searches in order to be broad in our definition of young people (defined as 14–24 years of age; Wellcome Trust, 2020), we did not exclude any studies as the number of studies was relatively small and we wished to be as inclusive as possible. All database searches were restricted to peer-reviewed English language articles published between January 1980 and July 2020.

Assessment of methodological quality

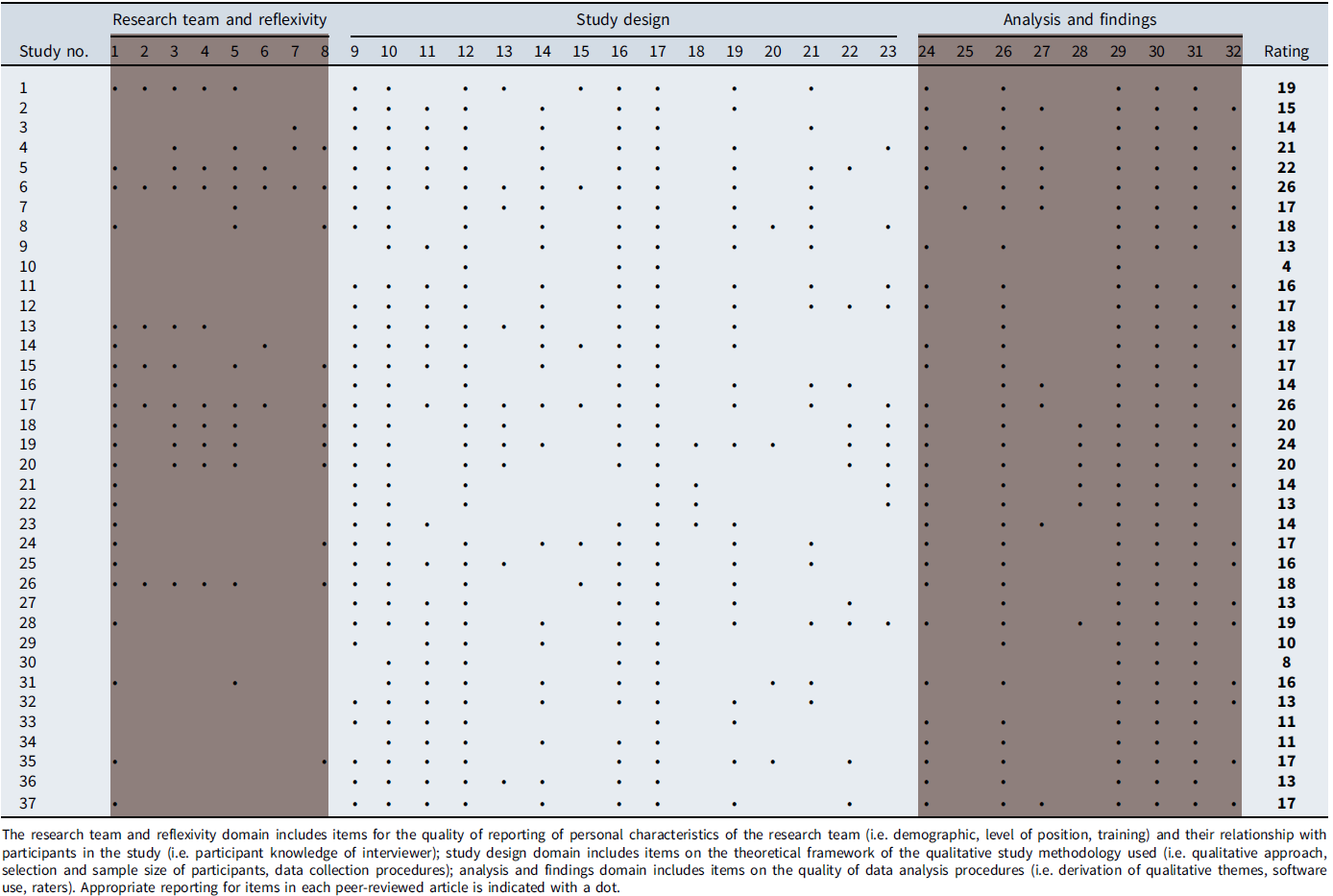

In line with PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009; Shamseer et al., Reference Shamseer, Moher, Clarke, Ghersi, Liberati, Petticrew and Stewart2015), the methodological quality of included articles was assessed. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ; Tong et al., Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig2007) rating scale was conducted by G.F. Quality ratings were discussed by authors; however, no studies were excluded due to low quality ratings scores, as per Sandelowski and Barroso’s (Reference Sandelowski and Barroso2006) recommendations.

Data extraction and synthesis procedure

The data extraction was performed by the primary reviewer (G.F.). As previously described in meta-synthesis literature (Malterud, Reference Malterud2019; Thomas and Harden, Reference Thomas and Harden2008), any information described by authors within the findings or results section of the paper was extracted for synthesis. Meta-synthesis was used for qualitative studies following established procedures (Lachal et al., Reference Lachal, Orri, Sibeoni, Moro and Revah-Levy2015; Sandelowski and Barrosa, Reference Sandelowski and Barroso2006). Similar to Ludvigsen et al. (2015), we were ‘third-order interpreters’ and quotes were included from participants (‘first-order interpreters’) and observations by authors (‘second-order’ interpreters). However, following Sandelowski and Barroso’s (Reference Sandelowski and Barroso2006) recommendations, the first order experiences of participants were highlighted through focusing on extracting quotes from the qualitative studies. All studies were read by the reviewer in full for familiarisation with the literature. Themes were cumulatively established as the reviewer sequentially reviewed and extracted information from the studies including existing quotations. This process was repeated a second time to enable the refinement of themes that were developed from the first extraction cycle. The research team were consulted regularly throughout this process and themes discussed with senior authors (S.E., T.W., R.S.) until consensus was reached. Methodological and participant characteristics were extracted from each study pertaining to author name, country, qualitative approach, sample size, participant age and gender (Table 1). Ethical approval was not required for the review.

Table 1. Study characteristics

* Data presented as a range or mean (SD). ED, eating disorder; NR, not reported; MT, mental toughness.

Results

Study identification and inter-rater reliability

As seen in the PRISMA flowchart in Fig. 1, the comprehensive search yielded a total of 3659 individual results, and 100% of these initial articles were screened by abstract and title by G.F. A secondary reviewer (A.O’B.) screened 30% of the articles by abstract. This resulted in 204 studies, of which 100% were assessed for eligibility by full text by G.F., based on a coding manual to ensure consistency. The coding manual contained information on the inclusion and exclusion criteria to record in an Excel spreadsheet by each rater in order to judge the criteria for the study eligibility. Blind, independent ratings of a random selection of 30% of full-text articles was performed by the second reviewer (A.O’B.). Moderate inter-rater agreement was calculated using Cohen’s kappa (κ = .624, p<.001), and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC = .529, 95% confidence interval: .102–7.53). In line with Watson et al. (Reference Watson, Joyce, French, Willan, Kane, Tanner-Smith, McCormack, Dawkins, Hoiles and Egan2016), a κ-value of 0.81–0.99 indicated near perfect agreement. Despite the inter-rater agreement only being moderate, following independent review, the two raters met to discuss discrepancies which were resolved in whole (κ = 1.00, p<.001; ICC = 1.00). On completion of full-text screening, 44 studies were identified as potentially relevant for the meta-synthesis and were reviewed by the research team. To further ensure consistency in rating and inclusion given the moderate inter-rater agreement, consensus was reached by T.W. and S.E., finding seven studies were not eligible based on inclusion criteria, leaving 37 eligible studies.

Figure 1. PRISMA Flowchart outlining study selection process.

Study characteristics

As seen in Table 1, 14 of the 37 included studies were conducted in the United States of America, eight in the United Kingdom, three in Canada, Australia and Sweden, and one in Switzerland, Cyprus, Chile, Denmark, South Africa and Germany. Among the included studies, authors used content analysis (n = 9), thematic analysis (n = 6), inductive data analysis (n = 5), interpretative phenomenological analysis (n = 2) and grounded theory (n = 2). Framework analysis, the Tesch method, plan analysis, cross case analysis, descriptive analysis and mixed content/thematic analysis were evident once. Five of the included studies did not explicitly report the qualitative method that they used. The mean age of participants was 24 years, and 73.5% were female.

While some studies were specific qualitative studies of perfectionism, others identified were qualitative studies in other areas, for example understanding suicidal ideation, where significant themes of perfectionism were mentioned by participants. Studies were included if they were not specific investigations of perfectionism as the qualitative findings were relevant to the questions regarding the association between perfectionism, anxiety and depressive symptoms in young people and hence were included in the meta-synthesis.

Study quality

The methodological quality ratings of each study can be seen in Table 2. The COREQ rating scale does not specify a cut-point guide for the interpretation of rating scores. The quality ratings for included studies ranged from 4 to 26 (mean = 16.16) out of a possible rating of 32.

Table 2. Quality ratings

Meta-synthesis

As seen in Table 3, there were numerous themes that emerged from the literature. For full quotes used to illustrate the themes, see Table S4 in the Supplementary material. There were many studies that described the key components of perfectionism, including for example high personal standards (n = 20 studies), drive for excellence and striving (n = 6 studies) and fear of failure and mistakes (n = 9 studies) (see Table 3; and Table S4 in Supplementary material).

Table 3. Meta-synthesis themes

Association of perfectionism with symptoms of anxiety and depression

Participants across the qualitative studies reported several negative consequences associated with perfectionism. Anxiety was a sub-theme of the over-arching ‘costs of perfectionism’ theme, and was mentioned in 10 studies, as seen in Table 3. Participants who were gifted students reported perfectionism being associated with ‘anxiety disorders and depressive problems’ (Gokaydin and Ozcan, Reference Gokaydin and Ozcan2018), ‘unrelenting anxiety and worry’ (Schuler, Reference Schuler2000), and high school students were ‘worried about parents’ reactions because of their high expectations’ (Neumeister et al., Reference Neumeister, Williams and Cross2007). Symptoms of anxiety were linked with perfectionism, for example high performance (sports, dance and musician) participants reported ‘anxiety and constant pressure experienced by participants by virtue of a perceived obsession with analysing one’s performances’ (Hill et al., Reference Hill, Witcher, Gotwals and Leyland2015), and gifted adolescents said ‘their fixation over making mistakes resulted in an almost continual state of high anxiety’ (Schuler, Reference Schuler2000). Similarly, stress was mentioned in quotes across seven studies (see Table 3). Depressive symptoms were mentioned in relation to perfectionism in 18 qualitative studies. For example, a university student stated it ‘… feels like the pressure to be “perfect” has mounted to an enormous level … and when I don’t succeed at something I become somewhat depressed …’ (Merrell et al., Reference Merrell, Hannah, van Arsdale, Buman and Rice2011). Guilt was also noted as a sub-theme of depression across four studies, for example ‘When you get a bad grade on a test, you feel bad inside, and when you are trying to go to sleep at night, you just feel guilt, like really bad, depressive guilt, like you did something seriously wrong that you should be ashamed of. And you have nobody to blame but yourself’ (Neumeister, Reference Neumeister2004b).

Self-worth dependent on achievement

There were seven studies identified (see Table 3) where perfectionism was associated with negative self-evaluation, for example ‘I think if I haven’t got something right, then I’m a bit of a worthless person. Or that I’m not good enough…’ (Riley and Shafran, Reference Riley and Shafran2005). Perfectionism was also associated with a theme of self-esteem and identity in 12 studies as seen in Table 3. For example, a first year university student reported ‘[If you get a bad grade] you feel incompetent, and that is one of the worst things you could ever be’, and university students reported that ‘achievement allowed them to maintain their self-worth’ (Neumeister, Reference Neumeister2004a).

Cognitive and behavioural maintaining factors of perfectionism

Cognitive and behavioural factors that maintain perfectionism (see Shafran et al., Reference Shafran, Cooper and Fairburn2002) were identified as themes across studies. Dichotomous thinking (e.g. viewing performance as either a complete success or a complete failure) was identified in 10 studies (see Table 3), for example in Hill et al. (Reference Hill, Witcher, Gotwals and Leyland2015) ‘rigid and dichotomous thinking’ were noted with participants’ stating ‘the only way to be the best musician is to just not accept any mistakes’ and ‘everything has to be black and white’. Self-critical thinking was noted in six studies (see Table 3), for example a first year university student stated ‘… instead of being a constructive evaluation, I just beat myself up over what I have failed to do…’ (Neumeister, Reference Neumeister2004b). A range of behavioural factors were also reported across studies, which may keep perfectionism going (Shafran et al., Reference Shafran, Cooper and Fairburn2002). For example, procrastination and avoidance was mentioned in six studies (see Table 3), for example a first year university student stated ‘If I am not good at something, I tend to avoid it’ (Neumeister, Reference Neumeister2004c). Similarly, excessive time devoted to performance was noted in five studies (see Table 3).

Perfectionism related to expectations of others (parents, family, friends, teachers)

A theme that was mentioned in 10 studies was related to the expectations and pressure on achievement experienced from family and others including friends and teachers. For example, ‘… expectations at home, when I lived with my parents, were far too great for me to handle in my teens … and surprisingly also in my early 20s, despite not living at home’, highlighting the role of expectations for performance from parents in university students who were interviewed regarding suicidal ideation and behaviour (Augsberger et al., Reference Augsberger, Rivera, Hahm, Lee, Choi and Hahm2018). Similarly, another participant reported ‘my parents put a lot of pressure on me to make good grades like my sister, I know they will be disappointed if I don’t, and while they never overwhelm me, I know the pressure is there’ (Merrell et al., Reference Merrell, Hannah, van Arsdale, Buman and Rice2011).

Effective elements of perfectionism interventions

There were few studies included in the meta-synthesis that evaluated participants’ qualitative feedback after engaging in treatment for perfectionism. In the study of Larsson et al. (Reference Larsson, Lloyd, Westwood and Tchanturia2018) after CBT for perfectionism for in-patients diagnosed with anorexia nervosa, participants particularly highlighted finding group treatment preferable over self-help, for example ‘having a group and talking about the ideas of how you can change is different to reading a book’ (Larsson et al., Reference Larsson, Lloyd, Westwood and Tchanturia2018). Furthermore, in this study participants highlighted the positive impact of CBT for perfectionism in a group format for helping to view their perfectionism in a different way in relation to others experiences, for example ‘… we’ve been able to challenge each other outside of the group and kind of make it into a bit of an awareness of perfectionism in terms of what perfectionism is and its associated behaviours and thoughts’ and ‘it was good to see that everyone wanted to be perfect in different ways … you always think you are the only person, so it was nice to see that there were other people that felt the same’ (Larsson et al., Reference Larsson, Lloyd, Westwood and Tchanturia2018). In another study examining internet delivered CBT for perfectionism, Rozental et al. (Reference Rozental, Kothari, Wade, Egan, Andersson, Carlbring and Shafran2020) reported qualitative feedback from participants emphasising the importance of guidance in this internet-based treatment, for example ‘this [guidance] appears to not only have provided them with support and encouragement, but also valuable feedback on things that were essential for moving forward. Some also pointed out that they probably would have missed out on significant aspects related to the understanding of their ongoing problems without this feedback’.

Potential barriers to treatment of perfectionism

Benefits of perfectionism were noted across 12 studies (see Table 3) by many participants, and these positive beliefs about the benefits of perfectionism are likely to be a significant barrier to young people engaging in treatment. For example, a participant from the high-performance sports and arts group in Hill et al. (Reference Hill, Witcher, Gotwals and Leyland2015) stated ‘well, I think there’s quite a lot [of advantages] because you achieve more just because you don’t accept low standards’. Similarly, a participant in the qualitative study of Ashby et al. (Reference Ashby, Slaney, Noble, Gnilka and Rice2012) with university students noted perfectionism was helpful as it led to ‘feeling good about accomplishments or success’. Further benefits identified as themes across a number of studies included participants reporting perfectionism helped with organisation (n = 5), working hard (n = 8), learning (n = 2), and achievement of goals (n = 7) (see Table 3). Participants also reported believing that perfectionism is associated with less stress, pressure and worry (n = 5), and that perfectionism led to admiration/recognition (n = 3) (see Table 3). Participants also reported across four studies (see Table 3) that perfectionism leads to success, for example a university student in the study of Rice et al. (Reference Rice, Bair, Castro, Cohen and Hood2003) reported ‘If you are going to be a perfectionist, you are going to accomplish a lot of things’ and in another study a participant reported ‘I think if I wasn’t [a perfectionist] then I wouldn’t have achieved things’ (Hill et al., Reference Hill, Witcher, Gotwals and Leyland2015).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to conduct a meta-synthesis of the qualitative literature relevant to understanding the link between perfectionism, anxiety and depression. The specific aims were to (i) help inform understanding of how perfectionism is associated with negative affect and (ii) inform future development of treatment for perfectionism in young people. Numerous themes were found across qualitative studies, representing the association of perfectionism with anxiety and depression, the definition of perfectionism and factors that keep perfectionism going, barriers to treatment and potential effective elements of treatment.

Perfectionism is linked to anxiety and depression

Perfectionism was reported to be associated with anxiety and depression across the qualitative studies (e.g. Gokaydin and Ozcan, Reference Gokaydin and Ozcan2018; Hill et al., Reference Hill, Witcher, Gotwals and Leyland2015; Neumeister et al., Reference Neumeister, Williams and Cross2007), and several of these studies were specifically with young people, for example adolescents (e.g. Schuler, Reference Schuler2000), first year university students (e.g. Neumeister, Reference Neumeister2004b) and university students with a mean age of 18 years (e.g. Merrell et al., 2018). These qualitative findings are in line with a meta-analysis that was not disaggregated by age but demonstrated a strong association between perfectionism and anxiety/depression (Limburg et al., Reference Limburg, Watson, Hagger and Egan2017) as well as quantitative studies in adolescents (e.g. Morgan-Lowes et al., Reference Morgan-Lowes, Clarke, Hoiles, Shu, Watson, Dunlop and Egan2019).

There are several possible routes by which we hypothesise perfectionism may contribute to anxiety and depression based on the cognitive behavioural model of clinical perfectionism (Shafran et al., Reference Shafran, Cooper and Fairburn2002). In clinical perfectionism, the emphasis of self-worth in a young person is on striving to meet unreachable standards, which can result in anxiety and depression when goals are not reached. The accompanying self-criticism associated with perceived failures exacerbates anxiety and depression and further reinforces self-worth based on achievement, which a young person then seeks to improve through further achievement, leaving them in a maintenance cycle of continued striving (Shafran et al., Reference Shafran, Cooper and Fairburn2002). The contexts that foster self-worth based on achievement may include having parents, teachers or peers who place pressure to attain high standards across different domains of life (e.g. study, appearance, sport), as highlighted in themes found in this qualitative meta-synthesis. Also implicated are widespread cultural shifts that increasingly emphasise competitiveness (Curran and Hill, Reference Curran and Hill2019) which may be increasingly dominant on some forms of social media. Future research should seek to conduct longitudinal studies on the role of perfectionism in the onset of anxiety and depression in young people, which in the area of eating disorders have clearly demonstrated perfectionism to be a risk factor in longitudinal studies examining the onset of symptoms (Wade et al., Reference Wade, Wilksch, Paxton, Byrne and Austin2015).

How qualitative studies can inform the refinement of CBT for perfectionism

There were consistent reports across qualitative studies that support the cognitive behavioural model of clinical perfectionism (Shafran et al., Reference Shafran, Cooper and Fairburn2002). This was demonstrated through evidence for quotes supporting self-worth based on achievement (e.g. Riley and Shafran, Reference Riley and Shafran2005), including in high school students (e.g. Neumeister et al., Reference Neumeister, Williams and Cross2007). There were also key elements of clinical perfectionism outlined in various studies with themes highlighting striving to achieve high standards and concern over mistakes. In support of the model were cognitive and behavioural processes that may keep perfectionism going highlighted across studies, including dichotomous thinking, avoidance and procrastination (e.g. Ashby et al., Reference Ashby, Slaney, Noble, Gnilka and Rice2012; Hill et al., Reference Hill, Witcher, Gotwals and Leyland2015; Neumeister, Reference Neumeister2004c; Rice et al., Reference Rice, Bair, Castro, Cohen and Hood2003; Riley and Shafran, Reference Riley and Shafran2005). In summary, these findings suggest the utility of CBT for perfectionism in young people (e.g. Shu et al., Reference Shu, Watson, Anderson, Wade, Kane and Egan2019), which focuses on targeting these processes.

There were potential barriers to effective treatment identified in many studies with participants believing perfectionism helps them achieve and even lowers pressure and stress (e.g. Ashby et al., Reference Ashby, Slaney, Noble, Gnilka and Rice2012; Hill et al., Reference Hill, Witcher, Gotwals and Leyland2015; Rice et al., 2015). These statements echo our clinical experience with treatment of perfectionism and highlight the importance of increasing motivation to change perfectionism (Egan et al., Reference Egan, Piek, Dyck, Rees and Hagger2013) based on various strategies outlined in CBT for perfectionism (see Egan et al., Reference Egan, Wade, Shafran and Antony2014). This may be particularly important in young people, where there are added potential barriers to treatment, for example the emphasis reported on experiencing pressure and expectations from others, including parents, which was associated with their perfectionism (e.g. Augsberger et al., Reference Augsberger, Rivera, Hahm, Lee, Choi and Hahm2018; Merrell et al., Reference Merrell, Hannah, van Arsdale, Buman and Rice2011). To date there have been limited studies examining the efficacy of CBT for perfectionism specifically in young people, and one area that may be important to consider when developing these interventions is a focus on the impact of parental expectations and peer pressure either in person or via social media.

Only two studies investigated participants’ qualitative feedback after specific treatment for perfectionism (Larsson et al., Reference Larsson, Lloyd, Westwood and Tchanturia2018; Rozental et al., Reference Rozental, Kothari, Wade, Egan, Andersson, Carlbring and Shafran2020) and both were with adults. Positive feedback from participants highlighted the importance of group delivery in one study (Larsson et al., Reference Larsson, Lloyd, Westwood and Tchanturia2018), and guidance in internet CBT for perfectionism (Rozental et al., Reference Rozental, Kothari, Wade, Egan, Andersson, Carlbring and Shafran2020). As neither of these samples were specifically young people, it is difficult to draw generalisations from these studies regarding recommendations for treatment in young people. It does, however, highlight critical gaps in the literature which are: (1) there are few specific studies examining treatment of perfectionism in young people and (2) the existing studies of CBT for perfectionism in youth (e.g. Shu et al., Reference Shu, Watson, Anderson, Wade, Kane and Egan2019) have not engaged in qualitative research.

The consultation of young people with lived experience of anxiety and depression is critical for future research to inform the content, delivery and preferences for treatment of perfectionism. There have been three studies in young people, which have demonstrated the efficacy of CBT for perfectionism in non-treatment-seeking community samples of children (Vekas and Wade, Reference Vekas and Wade2017) and adolescents (Nehmy and Wade, Reference Nehmy and Wade2015; Shu et al., Reference Shu, Watson, Anderson, Wade, Kane and Egan2019). While these studies have demonstrated a reduction in perfectionism and prevention of anxiety, depression and eating disorders in young people, there is a gap in knowledge regarding treatment effects of CBT for perfectionism in young people seeking treatment for anxiety or depression. As there are few treatment studies of perfectionism in youth, the first step in developing a treatment should be to understand the issue from the perspective of a young person. Based on the findings of this review, our current work is focusing on forming youth advisory groups for intervention studies for adolescents. The aim is to incorporate the views of young people with lived experience of perfectionism and its impact on anxiety and depression. Consequently, the findings addressed our aim of informing the future refinement and research for CBT for perfectionism, particularly with a focus for future research to incorporate the views of young people in informing future iterations of the treatment.

Clinical and treatment implications

What does this mean for clinical practice in developing an intervention for a young person with anxiety or depression? First, it is recommended to focus on a range of different domains of life that contribute to self-worth, which are not based only on achievement. Second, rigid all-or-nothing goals (e.g. ‘I must achieve 80% on this exam or I am a failure as a person’) should be challenged to develop more realistic and flexible guidelines (e.g. ‘I would like to achieve a good mark overall in the exam, but I am still a good person no matter what grade I receive’). Third, the conduct of behavioural experiments and other CBT techniques (see Egan et al., Reference Egan, Wade, Shafran and Antony2014) should address the specific cognitive processes that may keep perfectionism going, including the belief that perfectionistic practices are required for higher achievement (Osenk et al., Reference Osenk, Williamson and Wade2020). It is important specifically to focus on challenging ambivalence regarding changing perfectionism due to its perceived benefits as identified in this review. In summary, future research should further examine preliminary evidence for the efficacy of CBT for perfectionism in treating anxiety and preventing depression in young people (e.g. Shu et al., Reference Shu, Watson, Anderson, Wade, Kane and Egan2019). Specifically, research should examine if CBT for perfectionism can facilitate the prevention of escalation of early signs of anxiety and depression in young people.

Limitations

There were limitations of the review. First, few studies focused specifically on young people, and no qualitative studies reporting on treatment for perfectionism specifically with young people were found. Consequently, generalisations based on the synthesis should be interpreted in the context that the qualitative studies on treatment feedback were with adults rather than young people. Second, we did not specify age in the inclusion criteria due to the relative lack of studies in young people, hence despite the focus on young people the review also included qualitative studies with adults, and the mean pooled age of participants was 24 years, consequently generalisations to adolescents may be limited. Nevertheless, on average the pooled age of participants in the samples of 24 years indicates overall they were within our working definition of young people (Wellcome Trust, 2020). Third, we did not include a search of grey literature (e.g. dissertations, unpublished articles) or manual searching of journal articles, and it is likely that some relevant literature was missed in this category. Finally, although we discussed themes as a research team until consensus was met, there has been debate surrounding whether meta-syntheses contradict the epistemological positions of the qualitative research being synthesised and the role of meta-synthesis authors as third-order interpreters (Ludvigsen et al., 2015). Hence, there should be continued debate on the advantages and disadvantages of meta-synthesis (Ludvigsen et al., 2015). For example, Ludvigsen et al. (2015) have highlighted advantages of meta-synthesis as including the synthesis of findings into meta-summaries, but question the practical benefit of abstract themes and concepts for informing clinical practice. This emphasises the need to supplement meta-summaries with clear suggestions for intervention, so that a meta-synthesis is not based only on abstract concepts and themes, but can help inform clinical practice (Ludvigsen et al., 2015).

Conclusions

In summary, the qualitative literature broadly supports the idea that perfectionism plays an important role in anxiety and depression. While the literature is still in early development regarding the evaluation of treatments for perfectionism in young people, it holds promise as a treatment to target both anxiety and depression simultaneously given evidence of its transdiagnostic role (Egan et al., Reference Egan, Wade and Shafran2011; Limburg et al., Reference Limburg, Watson, Hagger and Egan2017). The critical importance of the lack of qualitative research and lack of engagement of young people as co-creating treatment interventions have been highlighted by this review, and we hope this stimulates further consideration of the importance of incorporating young people’s experience into the development of effective interventions for perfectionism.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

This work was funded by a Wellcome Trust Active Ingredients grant awarded to principal investigator Tracey Wade at Flinders University and (partly) funded by the NIHR GOSH BRC. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. Wellcome Trust had no role in the study design or interpretation of the findings, writing the manuscript or decision to submit the paper for publication.

Conflicts of interest

S.J.E., T.D.W. and R.S. co-authored and receive royalties for the self-help book ‘Overcoming Perfectionism’ referenced in this manuscript.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the review.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

S.J.E. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. G.F. performed the systematic review including database search, data extraction, thematic analysis, and quality ratings, and was a major contributor in writing the method and results. A.O’B. provided secondary ratings for the review. T.D.W. and R.S. were major contributors in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465821000357

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.