Introduction

In 1997, Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy published Melanie Fennell’s influential paper ‘Low self-esteem: a cognitive perspective’. Low self-esteem is common in various clinical populations. It can be an aspect of a presenting mental health problem and act to maintain it, a consequence of the experience of having mental health difficulties, and/or a vulnerability factor for problems such as depression, psychosis and eating disorders (e.g. Cervera et al., Reference Cervera, Lahortiga, Angel Martínez-González, Gual, Irala-Estévez and Alonso2003; Krabbendam et al., Reference Krabbendam, Janssen, Bak, Bijl, de Graaf and van Os2002, Sowislo and Orth; Reference Sowislo and Orth2013). Fennell’s model was based on Beck’s (1976) generic model of emotional disorders, and it was an important early example of a transdiagnostic approach. We are delighted to have the opportunity to propose some revisions to this model to help celebrate the 50th anniversary of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy and honour the lifetime achievements of Melanie Fennell and Aaron T. Beck.

Fennell’s (Reference Fennell 1997 ) original low self-esteem model

Fennell’s original model can be seen in Fig. S1 (see Supplementary material; reproduced with permission). In line with Beck’s (1976) general cognitive approach, Fennell (Reference Fennell1997) proposed that life experiences interact with temperament in the development of beliefs about the self. People with low self-esteem develop global negative self-beliefs which Fennell calls the ‘bottom line’, and are also often referred to as ‘core beliefs’ or ‘negative self-schema’. Examples might be ‘I am worthless/unlovable/unacceptable’. These core beliefs are associated with unhelpful conditional assumptions or rules for living. For example, someone with a core belief ‘I am failure’ might have a corresponding assumption ‘If I don’t succeed at everything I do, I am a failure’ and rule ‘I must do well at everything I do’. These assumptions and rules can allow the person to avoid high levels of distress that would otherwise be associated with the core belief, as long as they can meet the standards specified. However, when the individual perceives that their conditional assumptions and rules are not met, the core belief is activated. Activation of the core belief results in negative predictions (e.g. ‘I won’t be able to succeed at this task at work’) which can result not only in anxiety but unhelpful behaviours (e.g. avoidance, safety or compensatory behaviours) which can inadvertently prevent disconfirmation of the core belief. Fennell proposes that confirmation of the core belief results in self-critical thinking and in turn, depression. Depression increases activation of the core belief and thus, a vicious circle is set up. Fennell notes that the chronicity of low self-esteem relates to the ease and frequency of negative core beliefs activation and the availability of more positive, alternative self-views. Her model focuses on chronic rather than situational self-esteem.

Fennell’s model has been used to inform various individual and group-based treatments (e.g. Swartzman et al., Reference Swartzman, Kerr and McElhinney2021; Waite et al., Reference Waite, McManus and Shafran2012). A 2018 review of evaluations of interventions for low self-esteem in adults based on Fennell’s model identified seven publications (Kolubinski et al., Reference Kolubinski, Frings, Nikčević, Lawrence and Spada2018). Large effects were found for improvements in self-esteem (Hedges’ g 1.12 [0.97, 1.27]) and depression (–1.20 [–1.56, –0.84]) for the five studies of weekly individual or group sessions. Although the included studies were all from the UK and had significant limitations, such as high attrition rates and lack of follow-up data or appropriate controlling for confounding factors, these findings demonstrate the clinical utility of Fennell’s model.

Developments since the original model

Fennel’s model has been a huge influence on our work and those of others. However, theoretical and research developments over the past 25 years have occurred which might be usefully incorporated, such as those outlined below.

Social psychological theories

Two social psychological approaches to self-esteem are hierometer and sociometer theories (Leary et al., Reference Leary, Tambor, Terdal and Downs1995; Leary, Reference Leary2005; Mahadevan et al., Reference Mahadevan, Gregg, Sedikides and de Waal-Andrews2016). Both suggest that self-esteem is the output of monitoring for socially related threats. Hierometer theory suggests that self-esteem is a marker of one’s perceived level of status within social hierarchies, with status defined as being respected and admired (Mahadevan et al., Reference Mahadevan, Gregg, Sedikides and de Waal-Andrews2016). Sociometer theory proposes that self-esteem reflects the individual’s level of perceived relational value, i.e. being liked, accepted and included by others. It is suggested that such monitoring processes have evolved because social inclusion and successful management of social hierarchies are so important for survival. Mahadevan et al. (Reference Mahadevan, Gregg and Sedikides2019) propose that self-esteem has both sociometer and hierometer tracking functions and provide evidence to support this. Such theories imply that it could be helpful to distinguish between status and inclusion components in a model of low self-esteem, for example when considering core belief content and to help understand the aims and unintended consequences of some behavioural responses.

Research with people with socially disadvantaged characteristics

Research with people with socially disadvantaged characteristics could also inform a cognitive approach to low self-esteem. Socially disadvantaged group membership will not result in low self-esteem for members (for example, see work on social identity approaches about resilience and personal growth; Jetten et al., Reference Jetten, Haslam, Cruwys, Greenaway, Haslam and Steffens2017), but this paper suggests how it can contribute to low self-esteem for some individuals. We will provide examples from work about minority sexual orientation (e.g. being lesbian, bisexual, gay or queer).

We found that sexual minority individuals have lower self-esteem than their heterosexual counterparts (Bridge et al., Reference Bridge, Smith and Rimes2019) and that this may contribute to their greater risk for depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation and self-harm (Argyriou et al., Reference Argyriou, Goldsmith, Tsokos and Rimes2020; Argyriou et al., Reference Argyriou, Goldsmith and Rimes2021; Gnan et al., Reference Gnan, Rahman and Rimes2022; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Robinson, Oginni, Rahman and Rimes2017; Oginni et al., Reference Oginni, Robinson, Jones, Rahman and Rimes2019). This is consistent with Hatzenbuehler’s (2009) psychological mediation framework which suggests that stigma-related stressors increase cognitive, interpersonal and emotional regulation processes, including lower self-esteem, which mediate the impact of such stressors on mental health. Such research and theory suggest it could be important to include the role of interpersonal and cultural factors in a low self-esteem approach, for example through people with socially devalued characteristics experiencing increased risk for adverse interpersonal experiences which influence the formation of negative core beliefs and operate as triggering situations involving potential threat to one’s perceived value.

In qualitative analysis of interviews about self-esteem with sexual minority young adults, participants spoke about the adverse impact of negative social evaluations and reduced sense of belonging on their self-esteem (Bridge et al., Reference Bridge, Smith and Rimes2022a; Bridge et al., Reference Bridge, Smith and Rimes2022b). Many reported periods of social isolation and some had invested much effort in developing new relationships due to difficulties or rejection in their family relationships or community. Internalised stigma about their sexuality and/or self-criticism about its concealment often reduced their sense of their value and self-esteem. These interviews found evidence consistent with sociometer and hierometer theories that self-esteem fluctuations mirror changes in perceived competence or status and social connectedness and inclusion (Bridge et al., Reference Bridge, Smith and Rimes2022b). Furthermore, many strove to meet high standards in valued areas (e.g. education) and became self-critical when they perceived that they were failing to reach their expectations. Sometimes young people made explicit connection between striving harder to improve their self-esteem to try to compensate for their lower social acceptance or inclusion due to their sexual orientation. This is consistent with Pachankis and Hatzenbuehler’s (Reference Pachankis and Hatzenbuehler2013) suggestion that sexual minority individuals may place extra importance on what they call achievement-based domains (similar to the above-mentioned hierometer theory’s status domain), due to their stigma experiences. This suggests that a model of low self-esteem could include how responses to a threat in one domain could be associated with compensatory behaviours undertaken in the other domain.

Clinical observations

Our clinical observations when applying Fennell’s model also indicated some other potential revisions. For example, some negative appraisals reported by people with low self-esteem are not self-focused but other-focused, e.g. ‘He thinks I’m stupid because I made that mistake’. This suggests that a refined model could have a more general ‘negative appraisal’ component rather than self-critical thinking. Shame and self-disgust are often reported by people with low self-esteem but not included in the model. The model implies that depression may occur; however, many people with clinically significant low self-esteem do not have depression, but rather transient low mood. The model does not address how the unhelpful behaviours associated with low mood can maintain low self-esteem. It does not include the increased value-monitoring that patients report can often take place after a perceived threat to one’s value, which can take unhelpful forms (e.g. much time spent monitoring markers of one’s competence or social connections). Behaviours such as responses with a corrective or restorative function, including self-harm, are not addressed. The model does not specify how behaviours aimed at repairing the negative moods associated with core belief activation (such as excessive use of food, drugs, exercise or sex) can also be counterproductive and maintain core belief activation. Furthermore, it does not specify how the unhelpful behavioural responses undertaken adversely impact the person’s daily functioning and physical or mental health, which is turn negatively affect their success/achievements or relationships and hence strengthen negative core beliefs.

Refined cognitive behavioural approach to low self-esteem

We propose a refined cognitive behavioural model of low self-esteem development and maintenance. This builds on Fennell’s (Reference Fennell1997) seminal model, taking into account the theory, research and clinical observations outlined in the previous section. Our refined model has more emphasis on interpersonal, social and cultural factors. Examples will be given below for people with low self-esteem in the context of minority sexual orientation. However, the new model is aimed to be applicable to all with low self-esteem, not only those with socially disadvantaged characteristics.

Our refined model also explicitly includes the role of biological factors. This is in line with a biopsychosocial models, such as Engel’s (1979) classic biopsychosocial approach, which conceptualises how biological, psychological and social processes are all interconnected through feedback loops, resulting in reciprocal causal influences.

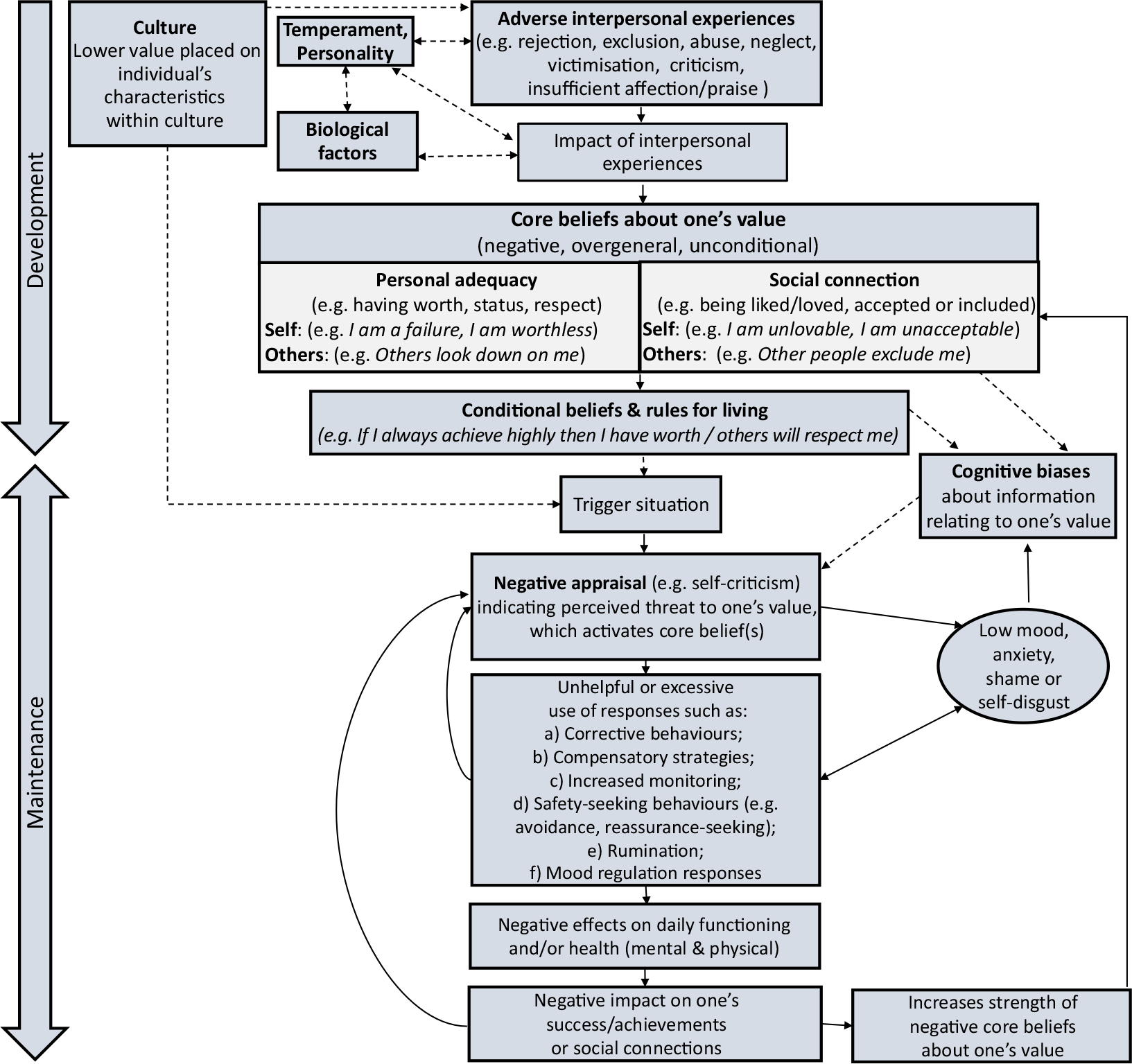

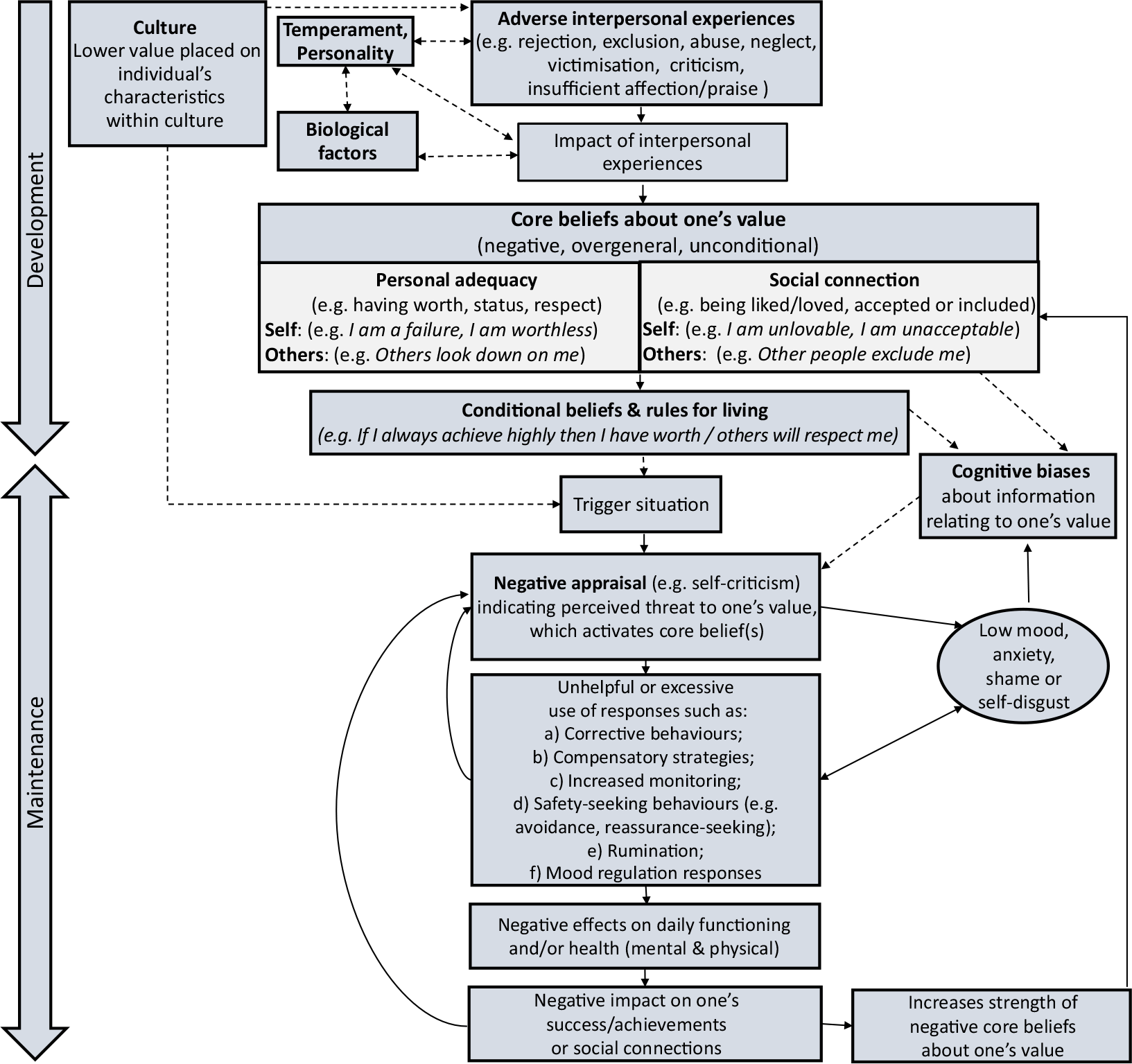

As shown in Fig. 1, the model has two parts: (a) the longitudinal development of ‘core’ or unconditional beliefs and associated conditional beliefs and (b) a maintenance cycle of low self-esteem. Continuous lines indicate the core causal processes in the model. Dashed lines indicate processes in which other important influences can also occur.

Figure 1. Refined cognitive behavioural model of low self-esteem (figure reproduced with permission).

Development of relevant core beliefs

Adverse interpersonal experiences

In line with Fennell’s (Reference Fennell1997) model, it is proposed that the development of negative core beliefs is influenced by adverse life experiences. In this refined model, it is suggested that it is adverse interpersonal experiences which are key for the development of low self-esteem, such as rejection, exclusion, victimisation, abuse, inadequate or conditional affection or praise, or criticism by others. Furthermore, these interpersonal experiences will be influenced by the social value placed on the individual’s different characteristics within their culture, such as their sex, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, appearance or abilities. For example, those with characteristics associated with lower social value will be more likely to have adverse interpersonal experiences such as exclusion, victimisation, criticism and lack of validation. There is evidence that such experiences are associated with lower self-esteem (e.g. Blais et al., Reference Blais, Gervais and Hébert2014).

Temperament and personality traits may influence both the likelihood of negative interpersonal experiences (e.g. van Os et al., Reference van Os, Park and Jones2001) and their impact; for example, neuroticism is characterised by greater vulnerability to the impact of stress (Amstadter et al., Reference Amstadter, Moscati, Maes, Myers and Kendler2016). Biological factors such as genes can play a role in self-esteem (e.g. Roy et al., Reference Roy, Neale and Kendler1995). Genetic factors have been found to modify the impact of adverse interpersonal experiences; for example, there is evidence that variation in a gene coding for oxytocin receptors might result in differential susceptibility to the impact of social exclusion on self-esteem (McQuaid et al., Reference McQuaid, McInnis, Matheson and Anisman2015). This relationship might also be reciprocal, with stressful interpersonal experiences having epigenetic effects (Lang et al., Reference Lang, McKie, Smith, McLaughlin, Gillberg, Shiels and Minnis2020).

Core beliefs

(a) Content: personal adequacy and social connection

Drawing on previous cognitive models (e.g. Beck, Reference Beck1976) and the above-mentioned social psychology models of self-esteem and research by our team and others about the impact of prejudice and discrimination, the refined model distinguishes between two key domains of beliefs in people with low self-esteem. The first set of beliefs relate to the individual’s lower perceived personal adequacy, for example having lesser worth, success in socially valued domains, respect or status (e.g. ‘I am worthless’/’Other people don’t respect me’). The second type relate to beliefs around poorer social connections, i.e. being less liked/loved, accepted, included and reduced belonging (e.g. ‘I am unacceptable’/‘Other people exclude me’). For both types of beliefs, it is suggested that perceptions of one’s value in the eyes of others is crucial. We use these terms for simplicity but acknowledge that no single terms adequately describe these broad domains, and therapists may prefer to use other terms.

Beliefs of either type are proposed to be sufficient for low self-esteem, although people may have both types and they may be closely related. For example, someone who believes that they are a failure may believe that as consequence this means they are unlovable or will be rejected. There is evidence that among people with low self-esteem, performance failure facilitates the processing of interpersonal rejection words more strongly than for people with higher self-esteem, indicating associations between performance and social connectedness (Baldwin and Sinclair, Reference Baldwin and Sinclair1996). The relationship between the personal adequacy and social connections domains can have implications for compensatory strategies, which are discussed more below.

People with stigmatised characteristics such as having a minority sexual orientation are more likely to report negative core beliefs about social connection (e.g. Nematy et al., Reference Nematy, Fattahi, Khosravi and Khodabakhsh2014). Examples are ‘I am different to other people/I am unacceptable’ and ‘Other people don’t accept me/reject me/exclude me’.

(b) Core beliefs about the self and others

In line the with greater emphasis on others’ perceptions of one’s value in determining one’s self-esteem, the refined model makes it more explicit that individuals with low self-esteem typically have a belief about others that corresponds to the negative self-beliefs. For example, beliefs that ‘I am a failure’ or ‘I am unlovable’ may have corresponding beliefs such as ‘Other people look down on me’ or ‘Other people don’t care about me’. Identifying both forms of beliefs and the extent to which they match or differ may be helpful. For example, the strength of the belief in the self-oriented form can be different than in the other-oriented form. Someone may completely believe that they are an unlovable person, but nevertheless believe to some extent that others love them, for example because others don’t know what they are really like or because parents generally have unconditional love for their children. Conversely, the individual may believe, for example, that ‘Other people think I am bad person because of my sexual orientation’ while the individual does not think that being lesbian, gay or bisexual makes them a bad person. This information could be used when addressing the self- and other-oriented beliefs and developing more positive alternatives.

People with low self-esteem may also have some positive beliefs about themselves, but it is assumed that there may be fewer, and the strength of positive beliefs and/or ease of activation is lower than for others. Conversely people who do not have low self-esteem may have negative beliefs about themselves, but it is suggested that these beliefs are less strong, generalised and easily activated. For people with socially devalued characteristics, the continued negative societal feedback act to strengthen the negative self-beliefs and negatively affect the development or strength of positive beliefs.

Conditional beliefs and associated behaviours

As in Fennell’s and general cognitive models, it is assumed that the individual develops conditional beliefs (sometimes previously termed ‘dysfunctional assumptions’) and ‘rules for living’ which relate to the unconditional core belief(s). For example, someone with a core belief ‘I am a failure’ may have a conditional belief such as ‘If I don’t achieve a consistently high performance at work, that means I’m a failure’ and rules such as ‘I must be highly successful at all work tasks’. These conditional beliefs/rules are associated with compensatory behaviours. For example, the individual might work very long hours, push themselves to achieve more and focus on their work despite detriment of other areas of their life. An example applicable to people with a concealable socially devalued characteristic might be ‘If others knew my sexual orientation, they would consider me unacceptable and reject me’ with the rule that ‘I must hide my sexual orientation from others’ and corresponding sexual orientation concealment behaviours.

As well as, or instead of developing conditional beliefs relating to the domain in which they believe themselves to be most lacking, people with low self-esteem may develop conditional beliefs associated with the other key domain to try to enhance their overall sense of value. For example, people with negative social connection core beliefs may develop beliefs and associated behaviours relating to compensation in a personal adequacy domain where it feels potentially possible to gain success and respect from others. Kresznerits et al. (Reference Kresznerits, Rózsa and Perczel-Forintos2021) found that seeking love and perfectionism were significant mediating factors in the relationship between depressive symptoms and low self-esteem. Someone with a minority sexual orientation may believe that although their sexuality is likely to be considered unacceptable to others, they may try to increase their personal achievements in an area that is socially valued, such as at work, sport or a hobby (Pachankis and Hatzenbuehler, Reference Pachankis and Hatzenbuehler2013). This has the effect of not only improving their sense of personal adequacy and status, and hence overall sense of value, but also has implications for their perceived social connection. For example, they may have a conditional belief that ‘People already think less of me for being queer, so if I don’t achieve highly at work, I will be rejected’.

Conversely, someone with negative beliefs about their personal adequacy may develop conditional beliefs and compensatory behaviours to increase their social connectedness value. Furthermore, they may believe that achieving markers of relationship success in relation to cultural standards (e.g. having a large social network, successful social life, getting married, having children) will help increase their sense of personal adequacy, status, and respect from others.

Maintenance of beliefs about low self-worth and social value

This model incorporates the above-mentioned social psychological perspectives which suggest that for everyone, self-esteem reflects an ongoing monitoring about one’s value. For people with a more adaptive balance of positive and negative beliefs about themselves, perceived threats to one’s value are assumed to result in helpful responses if needed. This could include identifying if any restorative action is required to address threats to one’s personal adequacy or social connections (e.g. directly addressing mistakes or interpersonal problems) and/or adaptive emotional regulation strategies. For example, someone with a socially devalued characteristic may attribute negative social feedback to prejudice/discrimination and either dismiss it or take action such as calling attention to the prejudice, attempting to educate the perpetrator or seeking support from others with similar characteristics (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Henderson and Rimes2020; Crocker and Wolfe, Reference Crocker and Wolfe2001). However, for people with negative core beliefs about their personal adequacy or social connectedness value, unhelpful responses are more likely, as discussed further below.

Triggering events

In the refined model, situational triggers to lower self-esteem are those which result in a threat to, or perceived reduction in, one’s value in relation to personal adequacy or social connection. Threats to meeting the conditions specified in the conditional belief (e.g. ‘Unless I maintain high standards at work all the time, I’m a failure’) mean that the underlying core belief (e.g. ‘I am a failure’) are activated. Examples of situational triggers include perceived failures, mistakes, social ‘faux pas’, rejection, exclusion or negative evaluations by others.

For those with socially disadvantaged characteristics, these experiences might be more frequent due to prejudice and discrimination. For example, for sexual minority individuals, triggers could include family rejection, homophobic/biphobic attitudes or victimisation, employment discrimination or stressors associated with ‘coming out’ or sexuality concealment (Bridge et al., Reference Bridge, Smith and Rimes2022a).

Cognitive biases

It is proposed that core and conditional beliefs relating to one’s value result in negative cognitive biases in attention, memory and interpretation (Everaert et al., Reference Everaert, Podina and Koster2017; Maheshwari et al., Reference Maheshwari, Kurmi and Roy2021; Rostosky et al., Reference Rostosky, Richardson, McCurry and Riggle2021). Biases in these automatic processes generally occur outside of conscious awareness and therefore may relate to ‘implicit’ self-esteem processes (Greenwald and Banaji, Reference Greenwald and Banaji1995). The results of these biases may be more open to conscious awareness, in the content of interpretations or appraisals of ongoing experience. For example, an interpretation of a mistake might be ‘I made a huge mistake, everyone must be laughing at me’ rather than an alternative ‘I made a little slip-up but it’s unlikely anyone noticed or cared’. The usual cognitive distortions specified in generic cognitive behavioural approaches apply, such as over-generalisation, mind-reading, discounting positive information, emotional reasoning, dichotomous or catastrophic thinking and so on. Examples from people with a minority sexual orientation might be ‘X is only being nice to me because they want to seem tolerant to LGBTQ people’; ‘People will automatically not like me when we first meet because I am queer’.

Negative appraisals and core belief activation

Negative appraisals of triggering events which are relevant to low self-esteem are those which indicate a threat to, or perceived reduction in, one’s value. This includes self-critical thoughts or thoughts about others’ negative perceptions of oneself. This threat perception increases activation of underlying negative unconditional and conditional beliefs about the self and/or value to others. As a result of increased activation of core beliefs and conditional assumptions, it is proposed that adverse mood effects and behavioural responses can occur which results in a vicious circle in which low self-esteem is maintained.

Low mood, anxiety, shame, self-disgust

Activation of core beliefs about low value in relation to personal adequacy or social connections increases negative emotions such as low mood, anxiety, shame and self-disgust (Goss et al., Reference Goss, Gilbert and Allan1994; Thew et al., Reference Thew, Gregory, Roberts and Rimes2017). These emotions can increase negative cognitive biases and hence the likelihood of further negative appraisals. They can also have a bi-directional effect with the behavioural responses outlined below.

Excessive or unhelpful responses

People with low self-esteem can undertake a range of different behaviours that are either unhelpful or used excessively, resulting in negative effects; key examples are outlined below.

(a) Corrective or restorative behaviours

After one has detected a threat to one’s value, some remedial action may be helpful, for example to address mistakes, failures or threats to relationships, to learn from our mistakes or difficulties and/or address associated distress in ourselves or others. However, for people with low self-esteem, responses can take on excessive or unhelpful forms. For example, people may apologise excessively or try to compensate when not needed, which can cause further threat to relationships or reduce their status in the eyes of others.

Self-punishing behaviours can occur including deliberate self-harm or withholding pleasurable activities. This may be due to a sense of deserving punishment and hence having a restorative function and/or a belief that such behaviours may lead to future self-improvement (Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Clarke, Hempel, Miles and Irons2004). If observed by others, behaviours such as self-harm may sometimes have a negative impact on how the individual is perceived, for example as someone who needs much support and cannot provide it to others. It can sometimes increase the risk of others, even therapists, acting with less compassion and care, thus impairing social connections and reinforcing negative core beliefs.

(b) Compensatory strategies

When an individual perceives failure and believes that this might not be adequately addressed by restorative or corrective action, they may undertake compensatory behaviours in another area of life where success seems more likely (Crocker and Park, Reference Crocker and Park2004). For people with low self-esteem, such compensatory strategies are often used excessively or inappropriately, for example when not required, due to their excessively negative appraisal (Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Broomhead, Irons, McEwan, Bellew, Mills, Gale and Knibb2007). Unfortunately, these can have unintended adverse consequences such as some listed below; see Crocker and Park (Reference Crocker and Park2004) for a detailed review.

Some compensatory responses will correspond to the individual’s conditional beliefs. As in Fennel’s model, such strategies prevent belief disconfirmation as the individual does not learn that their feared outcome (e.g. being a failure, rejection) does not necessarily occur in the absence of this behaviour. Such behaviours can be persistently in place to help prevent activation of the core belief but can also increase in frequency and rigidity as the perceived threat increases. Cognitive biases may occur in appraisals relating to compensatory behaviours, for example discounting positive experiences: ‘I can only achieve success by working much longer hours than other people which means I’m not as good as them’ or ‘X only values me because I do so much for them’).

When used excessively, compensatory strategies such as greater performance striving can be very time-consuming and demanding (Shafran et al., Reference Shafran, Egan and Wade2018). Perceived mistakes/failure to meet excessively high standards can lead to defensive reactions such as avoidance, anger and blaming (Farmer et al., Reference Farmer, Mackinnon and Cowie2017). People can be overly competitive rather than collaborative. Behaviours driven primarily by avoidance of negative core belief activation, rather than the enjoyable pursuit of valued goals, can also result in chronic dissatisfaction or a sense of disconnection with how the person feels inside, inauthenticity or identity confusion (Shafran et al., Reference Shafran, Egan and Wade2018).

Excessive performance striving can reduce the person’s ability to use other coping strategies including social support (Farmer et al., Reference Farmer, Mackinnon and Cowie2017). It can negatively impact on interpersonal relationships (Cameron and Granger, Reference Cameron and Granger2019). The poorer social connections and greater sense of social isolation (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2010, p. 112), can reduce one’s perceived or actual value to the self or others. Therefore, although excessive performance striving may be undertaken to try to compensate for negative beliefs about one’s acceptance or inclusion, unfortunately it can have the unintended consequence of ultimately increasing difficulties in social connections. This maintains or even worsens the negative core beliefs.

Conversely, strategies aimed at increasing one’s social inclusion, such as investing a large amount of time in improving and maintaining relationships, may come at a cost to one’s competence, performance or achievements in other areas. Such behaviours can also have other unintended consequences, for example others coming to expect a large amount of social support from the individual with low self-esteem. Sometimes the compensatory behaviours can lead to the individual feeling that no-one really knows them, if they are always striving to present themselves in ways that they perceive will increase social connectedness (e.g. always being positive, entertaining or supportive). At times this does indeed result in others not knowing what the individual really believes or feels, although others might detect that they are not connecting with the real person, with potentially adverse consequences for social connections.

Compensatory behaviours are often prioritised over self-care activities, for example in relation to sleep, nutrition, exercise, relaxation or personal grooming. Poorer self-care may also be associated with beliefs that they do not deserve it or caused by general low motivation associated with depressed mood. If persistent, inadequate self-care risks decreasing the person’s physical/mental health which may impact on their competence and success at valued activities in the short or longer-term. Such behaviours can result in reductions in social connectedness, for example an individual whose presentation reflects lack of self-care may be judged more negatively by others.

Pachankis and Hatzenbuehler (Reference Pachankis and Hatzenbuehler2013) found that gay men who focused their self-worth on academic achievement were more likely to report social isolation. Furthermore, the more that gay men based their self-worth on their appearance, the more eating problems they reported, and the more they tried to be better than others, the more likely they were to report dishonesty, distress and arguments.

(c) Increased monitoring of one’s value

Monitoring of one’s status or belonging increases as a result of perceived threat; this is assumed to be the case for many people temporarily, but in people with low self-esteem it is more likely to take on excessive or unhelpful forms. The type of monitoring behaviour depends on the domain valued to the individual. For example, in relation to personal adequacy, this may focus on markers of education or work performance, exercise/fitness or weight or shape and may take the form of detailed systematic monitoring using spreadsheets or apps. In relation to social connections, monitoring may focus on number of friends, dating or marriage success, number of ‘likes’ on social media, time taken for others to respond to one’s messages, and so on.

This monitoring takes place under the influence of attentional, memory and interpretation biases towards information that relates to a potential threat to their value. For example, upwards social comparisons are often reported by individuals with low self-esteem. Monitoring efforts can maintain focus on the feared outcome and associated distress, interfere with effective coping behaviours and trigger more self-critical appraisals or rumination.

(d) Safety-seeking behaviours

As a response to perceived threat, a range of different safety-seeking behaviours may occur. As with all safety-seeking behaviours, these prevent disconfirmation of unhelpful underlying beliefs (Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis1991). Examples of further consequences of avoidance and reassurance-seeking are provided below, but the therapist can also draw on disorder-specific approaches for formulation and treatment where appropriate.

Avoidance of situations which are associated with perceptions of low or reduced value in relation to competency/status or social connectedness often results in reduced opportunities for situations that could help to increase a sense of one’s value. For example, procrastinating about work can result in tasks being done at the last minute, possibly being associated with reduced quality or inconvenience to others, which will confirm negative core beliefs about personal adequacy or social connections. Social avoidance or withdrawal might be interpreted by others as being unfriendly or uncaring, resulting in negative social evaluations by others and adversely impact on the quality of one’s relationship or social inclusion. Avoidance of direct communication around difficulties and lack of assertiveness can mean that problems continue or worsen.

For people with concealable socially disadvantaged characteristics such as minority sexual orientation, avoidance can include attempting to hide one’s characteristic(s). This may reduce the risk of mental or physical mental harm due to others’ attitudes or social penalties, such as social exclusion and in some countries, imprisonment, physical punishment or the death sentence associated with minority sexual orientation. However, it can also prevent the individual from potential benefits such as improved relationships when the social context is not as dangerous as feared. Concealing aspects of the self can reduce the opportunities for meaningful interactions which could enhance social connectedness, especially when others perceive that the individual is hiding parts of themselves. Furthermore, sometimes the characteristic that the person tries to conceal is suspected or known to others which can make them not only subject to the usual stigma processes but also potentially attempts to ‘out’ or blackmail them.

Reassurance-seeking from others, designed to elicit a sense of increased safety, if used excessively can have detrimental effects on competence/status or social connections (Birgenheir et al., Reference Birgenheir, Pepper and Johns2010). For example, excessive reassurance-seeking in a work context could result in managers beginning to question the individual’s ability to cope or perform. Partners, family members or friends who feel that their affections are being tested may become frustrated, irritated or criticised, which may result in relationship difficulties.

(e) Rumination

Repetitive negative thinking or rumination can occur, focused on content relating to one’s personal adequacy or social connections. Examples may include asking oneself why one is not achieving as much as other people or why one is not being sufficiently accepted, included, liked or loved. Although often aimed at problem-solving, rumination can have a range of negative effects such as interfering with the individual attempting more helpful strategies including assertive communication; it can also be associated with meta-cognitive beliefs about rumination being dangerous or uncontrollable (Kolubinski et al., Reference Kolubinski, Marino, Nikčević and Spada2019) and maintain activation of core negative beliefs, low mood, anxiety or shame (Kuster et al., Reference Kuster, Orth and Meier2012; Rimes and Watkins, 1995; Watkins and Roberts, Reference Watkins and Roberts2020).

(f) Unhelpful mood regulation behaviours

It is proposed that compared to those with high self-esteem, people with low self-esteem feel less deserving of a positive mood after a perceived threat to their value than people with high self-esteem and less motivated to use mood-repair strategies that they know will be helpful (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Heimpel, Manwell and Whittington2009); further, when they do attempt mood-repair strategies they are more likely to use unhelpful responses. For example, people with low self-esteem can report excessive use of food, drugs, exercise, sex, sleep, productivity or deliberate self-harming behaviours which can have unintended consequences, including perceived or actual negative impact on performance or relationships (Crocker and Park, Reference Crocker and Park2004; McGee and Williams, Reference McGee and Williams2000). Furthermore, behaviours such excessive alcohol use, drugs, dieting or behaviours that inadvertently reduce sleep quality (e.g. overworking) can have short-term physiological effects that worsen mood. Long-term detrimental physical effects may occur from excessive use of alcohol, comfort-eating, exercising or risky sexual behaviours.

When growing up in a society which gives ongoing negative messages about their characteristic(s) such as minority sexual orientation, young people may be so frequently stressed that they rely on mood regulation strategies that provide quick short-term distress reduction. This can impair development of strategies that are more effective in the long term.

Consequences of unhelpful behaviours

Further negative appraisals often occur about the unhelpful behavioural responses outlined above. This can include self-critical thinking about not being able to cope effectively or using strategies that are ineffective or cause further difficulties or have a perceived negative meaning, e.g. ‘I am a fraud and a coward for hiding my sexual orientation’ (Bridge et al., Reference Bridge, Smith and Rimes2022b). This further contributes to the vicious circle, adding the direct negative mood effect of some of the responses or their consequences, such as the physiological effects of stress, excessive alcohol/drugs or inadequate sleep, nutrition or exercise.

As outlined above, the behavioural responses undertaken by people with low self-esteem to try to increase their perceived value in relation to personal adequacy or social connections often have unintended consequences with counter-productive effects, adversely affecting the person’s ability to achieve their personal achievement goals or positive social connections. Therefore, not only can the behavioural responses prevent disconfirmation of the negative core belief, these behaviours can contribute to a worsening of the person’s perceptions of their value, thus strengthening their negative core belief.

Relationship between low self-esteem and mental health problems

The processes described above can contribute to the development and maintenance of mental health problems. For example, unhelpful responses such as avoidance, rumination and dieting may play a role in clinically severe problems with anxiety disorders, depression and eating disorders. Such mental health problems have deleterious effects on the person’s daily functioning and health, negatively impacting on the individual’s perceptions of their personal adequacy and/or social connections, further maintaining low self-esteem.

Clinical implications

The refined model places more emphasis on interpersonal, social and culture contexts, and how low self-esteem relates to monitoring of one’s value in the eyes of others. The distinction between beliefs about personal adequacy or social connection, and how these may interplay, may be useful for formulation. For example, if it is identified that an individual has become excessively focused on improving personal adequacy to compensate for perceived lack of social connectedness, strategies may be helpful to not only address unhelpful success-related beliefs and compensatory behaviours, but to increase a sense of social connection. Individuals may wish to receive support around improving their social interactions or social networks. Conversely, individuals who focus much effort on their social connections in the context of core beliefs about low personal adequacy may want support in pursuing success in valued life domains, especially if avoidance or other unhelpful strategies are getting in the way.

Individuals with low self-esteem often present with beliefs such as ‘I am worthless’ or ‘I am a bad person’. It is difficult to envisage how such beliefs would develop in the absence of negative feedback or treatment from others, either subtle or explicit. Supporting the individual to identify how such beliefs have developed in an interpersonal context may help improve a self-compassionate metacognitive awareness about such beliefs and their perceived ability to address them.

It may also be helpful to identify and address separate beliefs associated with oneself and others (e.g. ‘I am a failure’, ‘Other people see me as a failure’) which often correspond, although not necessarily, or not to the same degree. For example, most of the time an individual may believe that others do not view them as a failure, but only because they maintain the compensatory behaviours related to their conditional belief such as putting in huge efforts to try to prevent or hide mistakes or failure. In Gilbert’s (Reference Gilbert2010) compassionate mind therapy he calls these types of beliefs ‘internal’ and ‘external’ fears; we often refer to these core beliefs as key fears about the self and others.

To inform the formulation, it may be helpful to assess different types of negative appraisals (e.g. self-critical thoughts and thoughts about others’ negative perceptions of oneself) and key unhelpful responses such as corrective behaviours, compensatory strategies, increased monitoring, safety-seeking behaviours, rumination and mood regulation responses. Similarly, specifically addressing the possibilities of reduced self-care and negative impact on one’s achievements/success or relationships in some situations may help increase awareness of the potential disadvantages of their behavioural responses. This may help to motivate the challenging work involved in changing typical responses.

Importance of interpersonal, social and cultural context

We suggest that the interpersonal, social and cultural context should be considered in formulations for all individuals with low self-esteem. When working with people with socially disadvantaged characteristics, the individual’s interpersonal and wider social experiences relating to these characteristics, such as sexism, racism or homophobia/biphobia, and how these intersect, can be discussed and included in the formulation if appropriate. It may be very validating to discuss how overt and subtle messages about having a socially devalued characteristic can have an understandable adverse impact on self-esteem.

The way in which the person’s individual characteristics interplay with their social context can help inform a more compassionate formulation of their difficulties. For example, sexual minority individuals may have restrictions on the range of effective coping responses available to them, for example due to their higher rates of mental health problems, lower levels of social support, fears about the consequences of sexual orientation disclosure, threats to be ‘outed’ to others, or fearing or encountering disbelief or lack of understanding. People with socially disadvantaged characteristics are often financially or otherwise more restricted in their coping responses. People with early trauma experience in addition to socially devalued characteristics may have particular difficulties in developing effective coping skills if they felt worthless and deserving of punishment, from the self and others, from a young age.

Intervention strategies should be planned which take into account the social context. For example, although sexual orientation concealment may have some costs to self-esteem and other negative effects, the individual may decide it is not psychologically or physically safe to come out in their current context.

A more self-compassionate understanding of one’s difficulties may also assist the individual to move towards greater acceptance not only of oneself but the reality of living in a society in which one’s characteristics are devalued. As discussed in third wave CBT approaches such dialectical behaviour therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy and mindfulness-based approaches, acceptance does not imply approval but can be an important precursor to enabling change. Addressing one’s unhelpful beliefs and behaviours does not preclude taking action to address societal prejudice and discrimination, and in fact may help the individual feel more able to take such action if they wish.

We developed protocols for working with people with a socially disadvantaged characteristic who wanted help for low self-esteem; one for people with any socially disadvantaged characteristic (Langford et al., Reference Langford, McMullen, Bridge, Rai, Smith and Rimes2021) and a second for sexual minority young adults (Bridge, Langford, McMullen, Rai, Smith and Rimes, submitted). These drew on traditional CBT and compassion-focused (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2010) intervention approaches. Uncontrolled acceptability and feasibility studies for these two new interventions, with young adults aged 16–24 years, indicated good acceptability, feasibility and preliminary evidence of improvements in self-esteem, functioning, depression and anxiety (Bridge et al., submitted; Langford et al., Reference Langford, McMullen, Bridge, Rai, Smith and Rimes2021).

Research implications

The processes specified in the refined model, and its clinical utility, require further research. As low self-esteem is a transdiagnostic process, much of the existing research evidence for the processes outlined above comes from people with specific mental health problems, and the research into social theory approaches is mostly based on general population rather than low self-esteem samples. Research is required to test out different aspects of the proposed model in people with low self-esteem, who do not necessarily have a current mental health problem. Research challenges include the difficulty of researching core beliefs due to them being idiosyncratic and not always easily accessible to conscious awareness although a ‘downward arrow’ technique may be helpful to identify them, not only clinically but in research (e.g. Millings and Carnelly, Reference Millings and Carnelley2015). The maintaining processes including the types of mood effects and behavioural responses can also vary widely between individuals and within individuals in different contexts.

The impact of social disadvantage on different core beliefs and the likelihood of triggering situations could also be investigated further in groups with different characteristics. For example, there is evidence from patients with depression that women were more likely to report core beliefs relating to relationships than men, i.e. relevant for the social connection domain, but the reverse was found for competence core beliefs, i.e. beliefs relating to the personal adequacy domain (Millings and Carnelly, Reference Millings and Carnelley2015).

Conclusions

Fennell’s (Reference Fennell1997) model has been important in guiding CBT interventions for low self-esteem. We have proposed a refined version which includes more focus on interpersonal, social and cultural factors. Our model also highlights mechanisms that were not prominent in Fennell’s model such as the distinction between different types of key core beliefs (personal adequacy and social connections; self and other-related), different types of unhelpful behavioural responses, and the potential negative impact on one’s competence and social connections that can result from such behaviours. Although consistent with existing research evidence, this model requires further investigation. We hope that the refined model will be useful for clinicians to support people with low self-esteem to develop a self-compassionate understanding of their unhelpful beliefs and behaviours and how to address them.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465823000048

Data availability statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the people with low self-esteem with whom we have worked in clinical or research contexts for sharing their experiences. We would also like to thank Helena Bladen, Jake Camp, David Hambrook and Sophia Kosmider for their very helpful feedback on a draft of this manuscript and to Monica Malhotra for her assistance with formatting.

Author contributions

Katharine Rimes: Conceptualization (lead), Writing – original draft (lead); Patrick Smith: Conceptualization (supporting), Writing – review & editing (equal); Livia Bridge: Conceptualization (supporting), Writing – review & editing (equal).

Financial support

None.

Conflicts of interest

Katharine Rimes is an Associate Editor of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. She was not involved in the review or editorial process for this paper, on which she is listed as an author. The other authors have no conflicts to declare.

Ethical standards

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conducted as set out by the BABCP and BPS.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.