Introduction

Over the past fifteen years, psychological services in England have been transformed by the introduction of the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme, which aimed to expand access to evidence-based psychological treatment for people with common mental health difficulties, such as anxiety and depression (Clark, Reference Clark2018; Richards and Whyte, Reference Richards and Whyte2009). One of the key features of IAPT is its adherence to clinical guidelines provided by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). NICE guidelines recommend a stepped-care model of service delivery, offering the least intrusive interventions first (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2011). Currently, the IAPT programme offers access to almost a million clients and treats over 560,000 clients per year (Clark, Reference Clark2018).

In addition to the more traditional High-Intensity CBT Therapist (HIT) role, IAPT introduced the Psychological Wellbeing Practitioner (PWP) role to ensure the provision of low-intensity CBT for mild-to-moderate anxiety and depression (Richards and Whyte, Reference Richards and Whyte2009; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Kellett, King and Keating2012). Low-intensity treatment can be delivered face-to-face, over the telephone or using online platforms. To undertake this work, PWPs complete a one-year undergraduate or postgraduate certificate in low-intensity CBT based on a national curriculum (University College London, 2015). Trainee PWPs are employed by IAPT services and spend roughly three to four days working in service, and the remaining days undertaking university work. PWPs receive a minimum of one hour per week of individual case-management supervision and also regular group clinical skills supervision (Green et al., Reference Green, Barkham, Kellett and Saxon2014).

IAPT services have consistently reported high levels of staff turnover in their PWP workforce (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2018). Whilst many PWPs move into high-intensity CBT training after two years of clinical experience (NHS England & Health Education England, 2016), research has highlighted that, despite receiving individual case-management and group clinical skills supervision, as well as general NHS and employer assistance support, PWPs experience high levels of stress and burnout, which might contribute to these high levels of turnover, including staff leaving IAPT altogether. Steel et al. (Reference Steel, Macdonald, Schröder and Mellor-Clark2015) found that PWPs’ stressful work involvement, and wider service-related issues such as service demands and autonomy, were the most significant predictors of burnout. Westwood et al. (Reference Westwood, Morison, Allt and Holmes2017) found that the prevalence of burnout was 68.6% among PWPs and 50.0% among HITs. Hours of overtime predicted higher levels of burnout and hours of clinical supervision predicted lower levels of burnout. The likelihood of burnout increased with the number of hours of telephone contact among PWPs who had worked in the service for two or more years. In the wider literature on therapist burnout, factors such as younger age, neuroticism, and emotion-focused coping have also been associated with higher vulnerability for burnout (Simionato and Simpson, Reference Simionato and Simpson2018). Delgadillo et al. (Reference Delgadillo, Saxon and Barkham2018) investigated the impact of occupational burnout on depression and anxiety treatment outcomes in IAPT, finding that therapist burnout had a negative impact on client treatment outcomes. Improving PWP retention is a key IAPT objective (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2018) and the National Health Service (NHS) in England has identified staff wellbeing as a critical factor in promoting resilience in its workforce (NHS England, 2016).

There have been numerous attempts to define and standardise the concept of resilience. Heterogeneity in adversity and risk experienced, as well as in the levels of competence obtained, has led to the development of competing ideas and definitions of resilience (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Cicchetti and Becker2000). However, despite this variability, many definitions encompass some common elements: exposure to significant levels of adversity, threat or trauma; the ability to recover from such experiences; and achieving better-than-anticipated outcomes (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Cicchetti and Becker2000; Masten and Barnes, Reference Masten and Barnes2018). Historically, research on resilience has focused on identifying risk and protective factors to understand how disadvantaged people, especially children, can thrive in adverse circumstances (Garmezy, Reference Garmezy1970; Garmezy, Reference Garmezy, Anthony and Koupernik1974).

More recently, research on resilience has shifted its focus towards understanding key underlying processes, putting emphasis on how these factors contribute to positive outcomes (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti2010). This new attention to the underlying processes of resilience is key to generating theories and identifying preventative and intervention strategies for people coping with adversity. Resilience has therefore been understood as the result of interactions taking place across multiple levels, shaped by processes occurring between the individual and the macro-level systems of culture, society and ecology (Masten and Barnes, Reference Masten and Barnes2018; Ungar, Reference Ungar2011). This study aims to draw on these newer understandings of resilience-building processes to explore the individual, organisational and psychosocial dynamics that contribute to the development of resilience in PWPs.

Due to the recent development of IAPT, research regarding PWPs has been scarce (Green et al., Reference Green, Barkham, Kellett and Saxon2014). There is very little research on resilience in PWPs, and existing research is mainly quantitative. A recent study in IAPT investigated the impact of mindfulness and resilience on therapist effectiveness, finding that more effective therapists reported higher levels of mindfulness and resilience, compared with less effective therapists (Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Barkham, Kellett and Saxon2017). Similarly, Green et al. (Reference Green, Barkham, Kellett and Saxon2014) found that PWPs whose patients had higher rates of reliable and clinically significant improvement, reported greater resilience and organisational skills, and felt more knowledgeable and confident in delivering therapy.

As can be seen, research on resilience in IAPT so far has focused on factors and associations investigated within cross-sectional analyses, rather than exploring how resilience occurs in PWPs and how they benefit from resilience-building processes. Existing theoretical models of resilience in other mental health professionals, such as social workers and family therapists, stress the importance of being able to adapt to challenging circumstances, the role of individual and environmental factors, the integration of practice within the self, the benefits of positive appraisals of adversity and the need to operate within a flexible environment where problems can be addressed effectively (Clark, Reference Clark2009; Van Breda, Reference Van Breda2011). These models can help to inform research on PWPs’ resilience as they can experience similar work-related and personal difficulties.

The aim of this study is to fill this gap in the existing literature by constructing a theoretically sufficient grounded theory (Strauss and Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1998) of the resilience-building process in the PWP role, and how this impacts on them personally and professionally. Making sense of this process of resilience-building can help services to address individual, occupational and organisational difficulties, and provide a greater understanding of what enables PWPs to thrive in the role, despite the chronic work-related stress they face.

Method

Study design

A critical realist perspective was taken, which postulates that the data, their interpretation and the related findings might not provide direct access to all reality as they only hold true within their specific contexts, structures and interactions (Bhaskar, Reference Bhaskar2008; Roberts, Reference Roberts2014; Willig, Reference Willig2013). Grounded theory was used to analyse the data, employing different coding strategies to identify categories of meaning that led to the development of a theoretically sufficient explanatory model. This study followed the methodological guidelines outlined by Strauss and Corbin (Reference Strauss and Corbin1998), which recognise the active role of the researcher in interpreting data and enhancing theoretical sensitivity (Corbin and Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2008).

Participants

The study recruited PWPs from two IAPT services within the same large NHS Mental Health Trust. Eligible participants were required to (a) be 18 years old or over, (b) have completed a one-year postgraduate or undergraduate certificate based on a PWP national curriculum, and (c) work as a fully qualified PWP within IAPT. The study did not aim to specifically target PWPs who described themselves as resilient. Rather, the study aimed to recruit participants who could talk about the process of developing resilience, and the potential challenges and barriers related to this process, regardless of whether they considered themselves resilient.

The recruitment of PWPs was facilitated by IAPT service leads, who cascaded relevant information about the study to PWPs in their service, who then contacted the first author if they were interested in taking part in the study. Eligible participants who expressed an interest were sent a participant information sheet and a consent form to sign prior to taking part in an interview. Ten participants (nine female and one male) were recruited. No eligible participants were excluded or dropped out from the study. The average duration of clinical experience since qualification was 27 months, ranging from 2 months to 12 years.

Participant confidentiality was preserved by anonymising recorded interview data, transcripts and verbatim extracts. Recruiting participants from more than one IAPT service also helped to ensure participant anonymity. Given the small sample size of this study, to ensure anonymity, participants’ demographic and socio-economic information was not included.

Data collection

Video-recorded semi-structured interviews were undertaken with PWPs. The duration of the interviews ranged from 54 to 80 minutes, with an average of 67 minutes. These were conducted remotely by the first author using Microsoft Teams. An interview schedule was utilised as an initial guide, including questions that explored the process of developing resilience in the PWP role. Open questions such as ‘what is resilience for you?’, ‘have you been able to develop resilience in your role?’, ‘how have you developed your resilience?’ and ‘what has helped you develop resilience?’ were included. The interview schedule remained flexible and open so that the conversation could be actively shaped by the participants’ reflections, views and language in a natural way. The iterative nature of grounded theory implied the progressive redefinition of the interview schedule within and across interviews, taking into consideration the emerging data, codes and analysis (Strauss and Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1998). Therefore, in line with theoretical sampling, interviews were transcribed and coded while recruiting participants. This iterative process was conducted until theoretical sufficiency, rather than saturation, was achieved. It has been proposed that theoretical sufficiency can be reached with 6–10 interviews (Clarke and Braun, Reference Clarke and Braun2013).

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed and the data analysed using a qualitative grounded theory methodology. This methodology was chosen as it allowed the researchers to generate an explanatory model of the conditions that gave rise to the process of developing resilience in PWPs, which was the main aim of this study, particularly as little was known about this process (Strauss and Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1998).

This led to the development of a theoretical model describing how PWPs build resilience in their role. The study followed the methodological guidelines set by Strauss and Corbin, which are based on a three-stage model of data analysis: open, axial and selective coding (Corbin and Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss1990; Corbin and Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2008; Strauss and Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1998). The analytical process was carried out using NVivo qualitative data analytical software (Release 1.5.2, 2021). Open coding involved an open-minded, line-by-line coding. The emerging codes were labelled to establish categories and a constant comparative approach was employed to achieve theoretical sufficiency. The second stage, axial coding, iteratively explored the relationships between codes, highlighting how they related to each other. This process was facilitated by the emergence of conditions, contexts, strategies, actions and interactions of categories, as well as the consequences of these. The third stage of analysis, selective coding, involved the identification of core categories or concepts, from which the theoretical model of the resilience-building process in PWPs developed. This model was obtained by conceptualising a storyline around the core category while constantly exploring the connections between this and the other categories identified in the analysis (Corbin and Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2008; Strauss and Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1998).

The development of all codes and categories, as well as the resulting theoretical model, were reviewed and discussed with the second and third author throughout the data analysis process. Data extracts were slightly edited to preserve anonymity and improve readability, when needed.

Reflexivity and rigour

Theorising contextual effects is one of the key advantages of qualitative research, which aims to gain awareness of participants’ views and settings, and the multi-level interactions between contexts (Cohen and Crabtree, Reference Cohen and Crabtree2008). Two authors of this study have worked as PWPs in the past. This direct experience enabled them to develop a better understanding of the participants’ contexts and perspectives (Yardley, Reference Yardley2000; Yardley, Reference Yardley2017), in line with the critical realist framework adopted in this research. In order to promote a trusting, open and transparent rapport, participants were made aware of the first author’s professional background prior to their interviews.

The first author used a self-reflective diary and memos to record significant events and acknowledge personal, social and cultural contexts throughout the research process. The diary helped the researcher to reflect on their own observations, experiences, interpretations and biases. The authors regularly met to discuss and agree on identified themes, and explore the development of the theoretical model. Furthermore, the project sought to ensure quality and rigour by using Yardley’s (Reference Yardley2000, Reference Yardley2017) evaluative criteria and framework, which informed and guided the research process.

Results

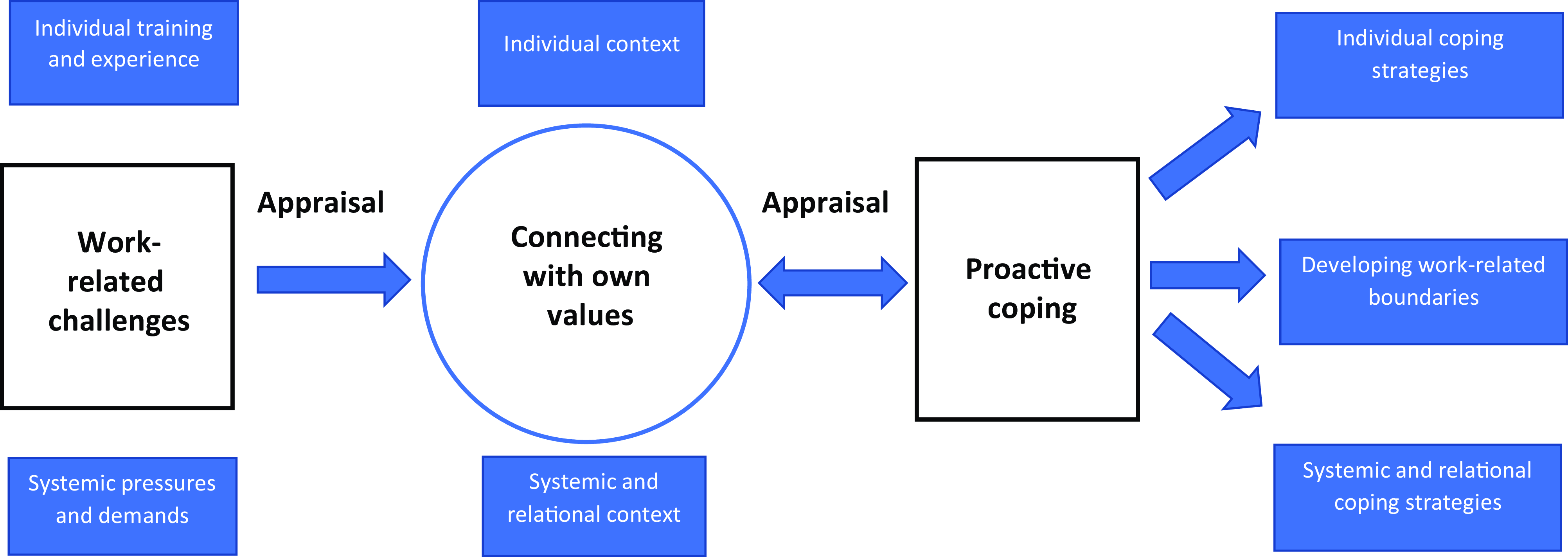

Participants described how the process of building resilience in their role developed through connection with their own values and the appraisal of work-related challenges in relation to those values. Three main phases of this theoretical model were identified: experiencing work-related challenges; connecting with their own values and appraising adversity in relation to those values; and implementing proactive coping strategies. This developmental process was established to have individual and systemic dimensions, which impacted on the development of resilience over time. Figure 1 shows the key elements of this dynamic resilience-building process. The arrows indicate how elements interlink, and the relationship between them.

Figure 1. Development of resilience in Psychological Wellbeing Practitioners.

Participants described how finding meaning and purpose encourages them to implement coping strategies when facing adversity, fostering their willingness and ability to cope with difficulties. Participants spoke about feeling that what they do matters and that they are in the role for a reason, which enables them to adapt to difficult circumstances and build resilience over time. They reflected on the meaning of ‘helping others’, ‘making a difference’ and ‘changing people’s lives’. This process of awareness of their values and how they are being nurtured through day-to-day work allows PWPs to navigate and overcome the challenges they experience in their role, reaffirming their sense of purpose and identity. For this group of PWPs this awareness is therefore a key part of the resilience-building process, and how they face and adapt to adversity more generally. Each part of the grounded theory model will be evidenced in turn.

Work-related challenges

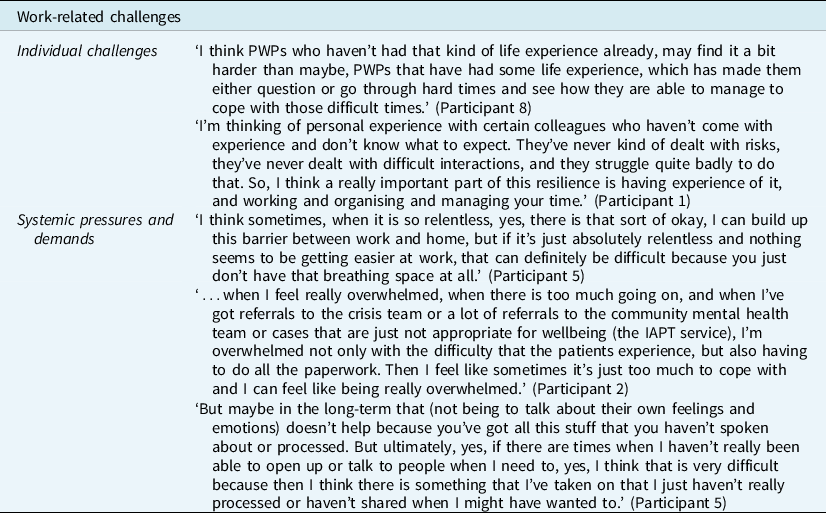

The first phase of the theoretical model is related to the difficulties PWPs experience in the role, which affect their experience of resilience. These challenges are important to consider as they are an integral part of the resilience-building process that occurs in PWPs over time. Two main dimensions were identified: systemic and individual challenges (see Table 1).

Table 1. Work-related challenges

Individual challenges

Individual challenges were mainly related to lack of professional and personal experiences. Participants highlighted how lacking personal or professional experience could contribute to the development of work-related challenges. Participant 8 talked about not having had particular life experiences prior to working as a PWP as a barrier to thriving in the role.

Lack of prior professional experience and training was also described as a significant challenge for PWPs, who may find it difficult to work clinically and manage their workload. Participant 1 highlighted the importance of prior work experience when managing risk and their time more generally.

Systemic pressures and demands

Participants emphasised the impact of the systemic challenges they experienced on their ability to develop and maintain resilience. Work-related pressures and demands, particularly the high volume of clinical work and the related time constraints, were identified as the main challenges that PWPs experience, as Participant 5 explained. Participants reflected on the difficulties associated with balancing administration and clinical work, particularly when managing risk and safeguarding concerns, as Participant 2 highlighted.

Participants also talked about the stress related to dealing with a high volume of clinical work and the lack of opportunity to reflect on it. Participant 5 spoke about the impact of not being able to process their own feelings and emotions, when needed.

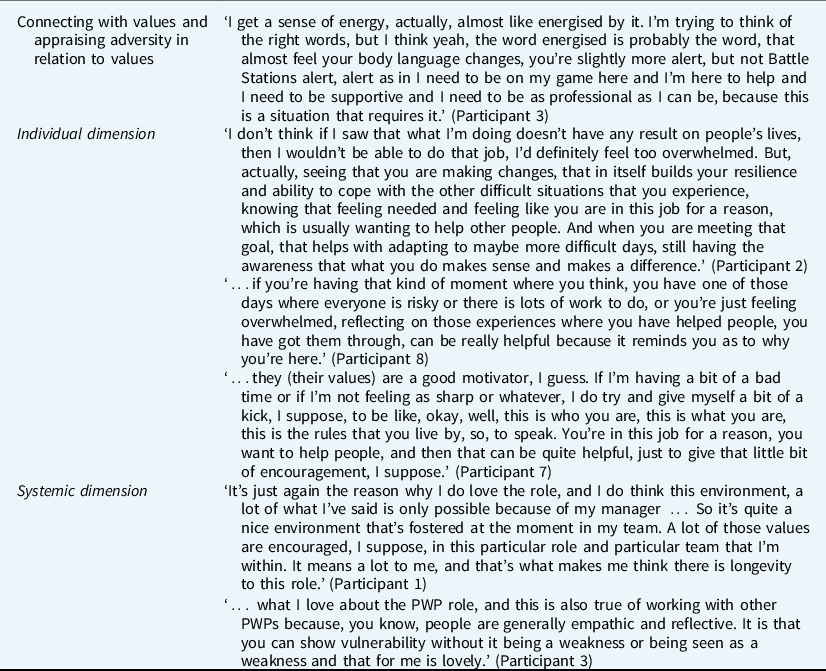

Connecting with values and appraising adversity in relation to values

The core category of this theoretical model was the participants’ connection with their own values and the subsequent appraisal of work-related adversity in relation to those values. Rather than experiencing challenges as overwhelming and unsurmountable barriers, getting in touch with their beliefs allowed the participants to place adversity in a wider context, acknowledging the need to overcome it in order to stay true to the values they believed in. Participants talked about how finding meaning in their day-to-day work encouraged them to take action and proactively implement coping strategies when facing challenges (see Table 2). Participant 3 described how powerful and motivating this process is. It is through this sense-making process that participants were able to adapt to work-related difficulties and develop resilience in their role. Similar to the first phase of the theoretical model, this core phase has an individual and a systemic dimension.

Table 2. Connecting with values and appraising adversity in relation to values

Individual dimension

Participants talked about getting in touch with their values when facing challenges as the key element of their resilience-building process. Finding meaning and purpose in their day-to-day work enabled them to build resilience over time, as Participant 2 explained. Participant 8 described how reminding themselves of the meaning of their work was particularly helpful when dealing with highly emotive situations. Participant 7 talked about how their values act as a motivator, encouraging them to implement coping strategies and take action when facing difficulties.

Systemic dimension

Participants highlighted that the process of connecting with their values and finding a sense of purpose in their work can also develop systemically and relationally. They shared how this sense-making process can be encouraged within the workplace by promoting a values-based culture, where PWPs feel they can stay and develop in the role despite the challenges they face, as Participant 1 explained.

Participants valued working in environments where they could share their vulnerability with their colleagues when facing difficulties, which enabled them to be open about what they found meaningful in their work.

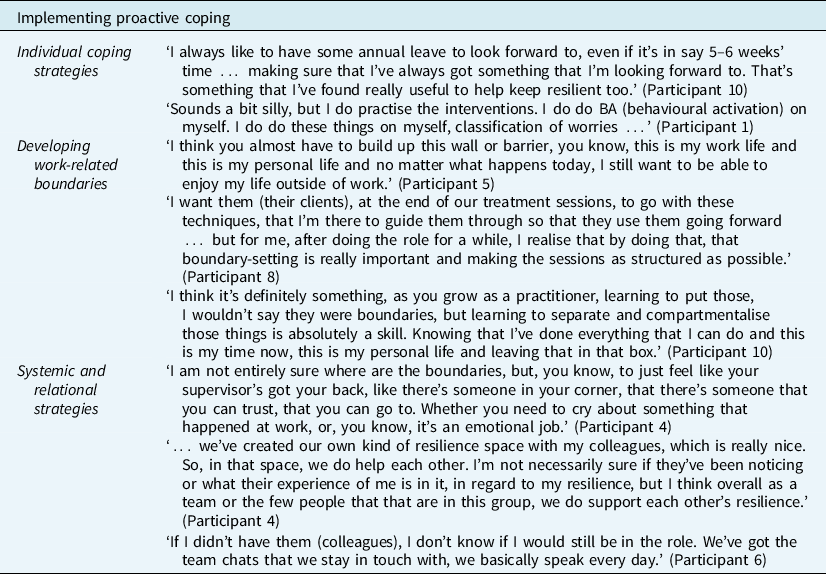

Implementing proactive coping

The final phase of the model involves the implementation of proactive coping strategies. Participants explained that getting in touch with their values and finding meaning in what they do encouraged them to implement strategies that helped them to overcome the barriers and the difficulties they faced, thus fostering resilience. This phase has three main dimensions: individual coping strategies, work-related boundaries, and systemic and relational strategies (see Table 3).

Table 3. Implementing proactive coping

Individual coping strategies

Several participants highlighted the importance of implementing self-care and wellbeing strategies in order to promote resilience, for example taking time off, having regular breaks and nurturing their hobbies and interests. Participant 10 talked about taking annual leave regularly to restore their wellbeing and stay resilient.

Participants also discussed the need to ‘practise what they preach’ to cope with challenges and thrive in the role. This included engaging in pleasurable activities, keeping a regular routine and practising the interventions they use in their clinical work, as Participant 1 stressed.

Developing work-related boundaries

Participants all reflected on the importance of developing work-related boundaries to build resilience. One participant talked about the need to separate work and personal life to be able to enjoy leisure time. Participants also highlighted the importance of managing their time effectively, keeping their clinical work structured. Participant 10 spoke about establishing work-related boundaries as a skill that PWPs can develop over time by compartmentalising work and private life.

Systemic and relational strategies

Participants discussed a number of systemic and relational strategies. Using clinical and case management supervision effectively and seeking peer support, when needed, were described as some of the most helpful strategies to develop resilience. Participants shared that they found supervision extremely beneficial to discuss clinical concerns, reflect on their development and contribution to the service, and to feel supported.

Peer support was considered invaluable by the participants. Talking to peers enabled them to process and normalise difficult feelings and emotions, at times even replacing clinical supervision. Participant 4 emphasised the key role of peer support in promoting resilience in the team. Another participant described how essential peer support is for them as it has helped them to stay in the role despite the challenges they faced.

Discussion

Given the enduring occupational stress and the high burnout and turnover rates in IAPT services (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2018; Owen et al., Reference Owen, Crouch-Read, Smith and Fisher2021; Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Morison, Allt and Holmes2017), this study sought to develop an explanatory model of the resilience-building process in PWPs to gain a greater understanding of how they overcome and adapt to work-related adversity. Participants described the process of developing resilience through three main phases. The first phase involved the experience of dealing with work-related challenges. The second and core phase of this process was the participants’ connection with their values and the subsequent appraisal of work-related difficulties. The third phase highlighted how participants developed resilience through the implementation of coping strategies, following their values-based appraisal of work-related challenges.

In line with existing conceptualisations of resilience involving other mental health professionals, such as social workers and family therapists (Clark, Reference Clark2009; Van Breda, Reference Van Breda2011), the current findings suggest that resilience involves the experience of adversity; implies the ability to adapt or ‘bounce back’; represents a dynamic and fluid process that occurs over time; and facilitates wellbeing and coping abilities. The findings seem to fit particularly well with recent conceptualisations of resilience as something relevant in the context of everyday difficulties, rather than solely in the context of significant adversity (Fletcher and Sarkar, Reference Fletcher and Sarkar2013), and also as something which involves the interaction of multiple systems or processes (Masten and Barnes, Reference Masten and Barnes2018; Ungar, Reference Ungar2011). The findings also mirror existing theoretical models of resilience in psychological therapists and mental health staff as a process of gradual adaptation to work-related challenges (Clark, Reference Clark2009; Van Breda, Reference Van Breda2011). Most importantly, the study highlighted that it is the values-based sense-making that PWPs go through that promotes the adoption of constructive attitudes towards overcoming adversity, thus fostering resilience.

For the current participants, the first phase of the resilience-building process described the experience of work-related difficulties. The difficulties associated with managing a large volume of clinical work and high caseloads appear to be significant barriers to PWP effectiveness, particularly when combined with poor or limited access to clinical support and supervision (Owen et al., Reference Owen, Crouch-Read, Smith and Fisher2021; Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Morison, Allt and Holmes2017). One potential explanation may be that practitioners who deal with a high volume of clinical work and experience time pressure find it hard to balance the available resources and demands they face. This imbalance fosters a perceived lack of control and autonomy in their role and limited participation in decision-making processes, which can lead to low job satisfaction, stress and burnout (Iannello et al., Reference Iannello, Mottini, Tirelli, Riva and Antonietti2017; Morse et al., Reference Morse, Salyers, Rollins, Monroe-DeVita and Pfahler2012).

The second and core phase of the grounded theory described the participants’ connection with their own values to appraise the difficulties they faced. Participants shared that getting in touch with their most meaningful values, such as wanting to help others and making a difference in people’s lives, enabled them to develop resilience. Most of the relevant literature on therapist burnout has emphasised the need to target negative factors in order to reduce burnout (Morse et al., Reference Morse, Salyers, Rollins, Monroe-DeVita and Pfahler2012). The findings of this study stress the importance of exploring sense of purpose and meaning in order to increase therapist involvement, job satisfaction and resilience. It is possible that the focus on achieving national targets in IAPT services moves therapists away from their true values and aspirations, which affects their sense of agency, and their willingness and ability to adapt to challenges. As other conceptualisations of resilience have theorised, the role of values and beliefs is key in appraising work-related stressors as comprehensible, manageable and meaningful (Hou and Skovholt, Reference Hou and Skovholt2019; Van Breda, Reference Van Breda2011).

The third phase of the resilience-building process in PWPs described the implementation of individual, work-related and systemic coping strategies. PWPs seem to elicit resilience through the use of wellbeing and self-care strategies, such as taking breaks, having time off and engaging in pleasurable activities. It appears that the emphasis on their wellbeing and the related engagement in meaningful and enjoyable activities allows PWPs to detach from work-related concerns and focus on cultivating their own interests. Research has suggested that the regular implementation of self-nurturing behaviours fosters therapists’ ability to develop their sense of identity (Hou and Skovholt, Reference Hou and Skovholt2019). Similarly, PWPs with strong work-related boundaries, such as good organisational and time-management skills, tend to be more resilient and proactive in their approach, as well as more clinically effective (Green et al., Reference Green, Barkham, Kellett and Saxon2014). Therapists with firm work-related boundaries are less likely to take on additional tasks and work overtime, thus maintaining high levels of resilience and preventing burnout (Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Morison, Allt and Holmes2017). The systemic and relational strategies discussed by the participants of this study included relying on peer support, managerial and clinical supervision. Therapists seem to elicit support, encouragement and normalisation of their difficulties through the interactions with their peers, reducing self-doubt and increasing self-confidence (Clark, Reference Clark2009; Jones and Thompson, Reference Jones and Thompson2017). Feeling supported by the supervisor and building a positive relationship based on trust has been shown to boost therapist resilience (Rothwell et al., Reference Rothwell, Kehoe, Farook and Illing2019). This trusting relationship facilitates open and honest discussions in which beliefs and values can be explored safely, thus encouraging therapists to stay true to their belief system (Rothwell et al., Reference Rothwell, Kehoe, Farook and Illing2019).

Clinical implications and recommendations

Staff wellbeing and retention are significant areas of concern for IAPT services as practitioners deal with a very high volume of clinical and non-clinical work, which contributes to the long-standing work-related challenges they face. Understanding the processes that support the development of resilience in clinical roles therefore has the potential to address these concerns. These are important issues to tackle as poor wellbeing has been associated with a higher intention to leave the NHS (Summers et al., Reference Summers, Morris, Bhutani, Rao and Clarke2020) and low levels of resilience have been associated with higher levels of stress in PWPs (Owen et al., Reference Owen, Cross, Mergia and Fisher2022).

The process of developing resilience described by the participants highlighted the key role of values-based sensemaking and the subsequent use of effective coping mechanisms in managing work adversity. Services should consider the promotion of a values-based culture where therapists feel able to nurture their beliefs and values, as this has been shown to encourage the appraisal of work-related difficulties in resilient ways (Van Breda, Reference Van Breda2011). The importance of establishing a values-based culture has been emphasised by the UK’s NHS, which has consistently promoted its core values and principles through the publication of the NHS Constitution (NHS England, 2013). Services could consider the use of self-awareness and reflective practices, such as mindfulness-based activities and narrative exercises exploring meaningful clinical experiences, as these have been shown to enhance sense of purpose and job satisfaction, thus increasing resilience in the workplace (Krasner et al., Reference Krasner, Epstein, Beckman, Suchman, Chapman, Mooney and Quill2009; Morse et al., Reference Morse, Salyers, Rollins, Monroe-DeVita and Pfahler2012; Robey et al., Reference Robey, Ramsland and Castelbaum1991).

Services should promote self-care and wellbeing strategies, and encourage therapists to maintain effective work-related boundaries. It is important for services to regularly emphasise and promote these strategies to nurture a culture of compassion and empathy for both clients and staff, where ethical practice is nurtured. As also acknowledged by NHS England, effective leadership (NHS Leadership Academy, 2013), training and supervision all contribute to fostering this organisational culture in services (Robey et al., Reference Robey, Ramsland and Castelbaum1991; Shakeel et al., Reference Shakeel, Kruyen and Van Thiel2019; Simionato et al., Reference Simionato, Simpson and Reid2019). Therapist wellbeing should also be supported systemically through the development of peer networks. This can be achieved by designing initiatives that bring professionals together, such as practice-based courses and training, relaxation and leisure activities (Simionato et al., Reference Simionato, Simpson and Reid2019).

Limitations and future areas of interest

Being a qualitative study, this research does not aim to generalise its findings to other populations of PWPs in a statistical sense (Myers, Reference Myers2000). However, quantitative and mixed-method studies with larger sample sizes can seek to build on these findings, and might achieve further generalisability and provide more insight into the process of developing resilience in PWPs.

This study did not use any measures of resilience that could have helped to contextualise the sample and, in turn, the findings. Future research on resilience in PWPs could therefore include specific measures of resilience to further contextualise the sample, the settings and the findings.

As all qualitative research is inherently subjective (Starks and Trinidad, Reference Starks and Trinidad2007), the authors’ personal opinions and biases might have influenced the interview process, transcription, analysis and interpretation of data, as well as the related findings. Therefore, it is important to acknowledge potential issues of bias, credibility, coherence and transparency (Yardley, Reference Yardley2000; Yardley, Reference Yardley2017). However, the authors mitigated these risks by enhancing rigour and trustworthiness, particularly through the implementation of techniques that make participants feel at ease during interviews, such as rapport building, the use of reflexivity tools, such as reflective diaries and memos, and regular peer debriefing and scrutiny. Future research could build on these findings to increase transferability between services and contexts, and more generally the breadth of therapist experiences. While this research did not aim to generalise its findings, the patterns, experiences and perspectives included in this study could be applicable to other contexts and settings, such as those related to other psychological therapists and mental health staff. This could be achieved, for example, by carrying out studies with larger sample sizes and involving other IAPT therapists and practitioners, such as HITs, counsellors and psychologists. Studies including students and trainees might provide a deeper developmental understanding of the resilience-building processes in PWPs.

Conclusion

This study aimed to develop an understanding of the resilience-building process in the IAPT PWP role through qualitative interviews with a small sample of PWPs. Findings highlighted that this cohort of PWPs developed resilience through the connection with their values and appraising the challenges they faced in relation to their beliefs and values. For the participants getting in touch with their values enabled them to find meaning and purpose in their difficulties, which enabled them to overcome adversity, including through using effective coping strategies. Given the enduring occupational challenges IAPT practitioners deal with, services and training programmes should promote a values-based culture where PWPs can be true to their values and encourage the use of effective individual and systemic coping strategies. Further research with larger sample sizes and different methodological approaches is needed to increase transferability.

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of the research, supporting data are not available.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the PWPs who participated in the study, sharing their thoughts, experiences and reflections, without which this research would not have been possible.

Author contributions

Marco Vivolo: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Resources (equal), Software (equal), Validation (equal), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Joel Owen: Conceptualization (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Supervision (supporting), Validation (supporting), Visualization (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Paul Fisher: Conceptualization (supporting), Formal analysis (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Project administration (equal), Resources (supporting), Supervision (lead), Validation (supporting), Visualization (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting).

Financial support

This research was carried out as part of the first author’s doctoral thesis for the Doctorate in Clinical Psychology at the University of East Anglia. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. This study requested and gained ethical approval from the NHS Research Ethics Committee (IRAS N. 292357) and the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences at the University of East Anglia (reference: 2020/21-047). Any necessary informed consent to participate in the study and for the results to be published was obtained.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.