Previous research focusing on stress and subsequent burnout of special education (SE) teachers has overlooked multidimensional aspects of SE teacher wellbeing (SETWB). Of the limited research positioning SETWB as a positive state, separate from stress and burnout, few studies provide a clear definition. After consideration of existing definitions of wellbeing, this paper offers a definition of contemporary perspectives of teacher wellbeing. Furthermore, we argue SE teachers have context-specific promoters and inhibitors of occupational wellbeing that operate differentially to their mainstream colleagues. SE teacher-specific factors emerging from the literature are examined through a teacher wellbeing framework. In the Australian context, SE teachers in New South Wales (NSW) and Tasmania are discussed and compared, highlighting the diversity of roles within and between school systems. The paper intentionally focuses on the wellbeing of SE teachers, integrating literature from outside this scope to build a contextual understanding of the differences in SE and general teacher occupational wellbeing.

The purpose of this paper is not to diminish the excellent and illuminating work that has gone before, but rather to espouse the critical need to understand specific impacts on the complex SE teacher role and build upon collective wisdom to unearth factors promoting SETWB beyond absence of stress and burnout. Separating stress and burnout from wellbeing provides an avenue for understanding the unique and complex concept beyond curing ailments (Bower & Carroll, Reference Bower and Carroll2017; Hascher & Waber, Reference Hascher and Waber2021; Kouhsari et al., Reference Kouhsari, Chen and Baniasad2023; Lummis et al., Reference Lummis, Morris, Ferguson, Hill and Lock2022; Sharrocks, Reference Sharrocks2014).

Stress and burnout are focused on negative human emotions, often described in terms of needing amelioration to move toward or achieve greater wellbeing (Collie et al., Reference Collie, Malmberg, Martin, Sammons and Morin2020; Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2020). This exclusive focus on teacher pathology ignores the critical role positive affect and purposeful and systematic enablers have empirically shown to have on increased human wellbeing, such as self-determination, self-efficacy and connectedness (Collie et al., Reference Collie, Shapka, Perry and Martin2015; Olsen & Mason, Reference Olsen and Mason2023; Renshaw et al., Reference Renshaw, Long and Cook2015; Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2020). Studies concerning teacher stress and burnout are problematic, as they imply that the absence of stress and burnout is evidence alone of wellbeing (Billingsley & Cross, Reference Billingsley and Cross1992; Bower & Carroll, Reference Bower and Carroll2017; Diener et al., Reference Diener, Suh, Lucas and Smith1999).

Often used interchangeably, stress and burnout represent distinct experiences and implications for teacher wellbeing. Stress is a natural response to job demands such as workload and time pressures (Brunsting et al., Reference Brunsting, Sreckovic and Lane2014; Cancio et al., Reference Cancio, Larsen, Mathur, Estes, Johns and Chang2018; Platsidou & Agaliotis, Reference Platsidou and Agaliotis2008), whereas burnout has been described as the result of chronic stress, resulting in a state of physical and emotional exhaustion (Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Forrest, Sanders-O’Connor, Flynn, Bower, Fynes-Clinton, York and Ziaei2022; McDowell, Reference McDowell2017; Riley, Reference Riley2014). There is a distinction in the literature between teacher stress, burnout and wellbeing where teacher wellbeing is conceptualised not as an absence of stress but rather the creation of an environment supportive of teachers’ emotional and physical needs (Cancio et al., Reference Cancio, Larsen, Mathur, Estes, Johns and Chang2018; Hester et al., Reference Hester, Bridges and Rollins2020; Kaynak, Reference Kaynak2020; Kim & Lim, Reference Kim and Lim2016; Platsidou & Agaliotis, Reference Platsidou and Agaliotis2017; Wessels & Wood, Reference Wessels and Wood2019). There has been much focus on SE teacher burnout and stress within educational research and how to best mitigate these factors to boost wellbeing (Brunsting et al., Reference Brunsting, Sreckovic and Lane2014; Cancio et al., Reference Cancio, Larsen, Mathur, Estes, Johns and Chang2018; Herman et al., Reference Herman, Sebastian, Eddy and Reinke2023; Hester et al., Reference Hester, Bridges and Rollins2020; Kiel et al., Reference Kiel, Heimlich, Markowetz, Braun and Weiß2016), further perpetuating the myth of wellbeing as an absence of stress and burnout.

Teacher wellbeing research is not new (see Figure 1). However, there is scant robust empirical teacher wellbeing research specific to SE teachers in Australia, a sector of the education profession tasked with the responsibility to educate students who experience lower educational outcomes compared to their peers (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2020, 2022; Rendoth et al., Reference Rendoth, Duncan and Foggett2022). SE teachers can be subject to pressures from challenging student behaviour, complex and chronic disability caseload management, multiple role statements (applied and assumed), student achievement and lack of tenure in their current position (Cancio et al., Reference Cancio, Larsen, Mathur, Estes, Johns and Chang2018; Olagunju et al., Reference Olagunju, Akinola, Fadipe, Jagun, Olagunju, Akinola, Ogunnubi, Olusile, Oluyemi and Chaimowitz2021; Rae et al., Reference Rae, Cowell and Field2017). Conversely, SE teachers have been found to experience higher levels of wellbeing due to smaller class sizes, greater student connection and ability to address skills relevant to life outside school as part of the curriculum for students with disabilities (Fox et al., Reference Fox, Tuckwiller, Kutscher and Walter2020; Pavlidou & Alevriadou, Reference Pavlidou and Alevriadou2022; Rae et al., Reference Rae, Cowell and Field2017).

Figure 1. Published Research on Teacher Wellbeing From 2000 to 2023 — Scopus Results.

In response to the post-pandemic teacher (mainstream and SE teachers) shortage in Australia (Craig et al., Reference Craig, Hill-Jackson and Kwok2023; Mrstik et al., Reference Mrstik, Pearl, Hopkins, Vasquez and Marino2019), the Australian Government Department of Education National Teacher Workforce Action Plan emphasised the urgent need to improve teacher supply, working conditions, and status (Australian Government Department of Education, 2022). Pre-pandemic, retention of SE teachers in NSW was highlighted in a parliamentary enquiry in 2010 (NSW Parliament, 2010) and emphasised by Dempsey and Christenson-Foggett (Reference Dempsey and Christenson-Foggett2011), who call for increased scholarly interest into high SE teacher turnover in Australia.

Ensuring wellbeing of SE teachers is crucial for the future of quality inclusive education as they play a vital role instructing marginalised students — those with disability. This imperative — to support legislators, administrators, school executives, teachers, and other relevant stakeholders to engage with, and be cognisant of, the impact of SETWB (Brunsting et al., Reference Brunsting, Sreckovic and Lane2014) — underpinned three guiding questions for this review:

-

1. How is teacher wellbeing defined?

-

2. How do SE teachers’ roles differ from their mainstream colleagues?

-

3. What impacts and promotes SETWB?

Teacher Wellbeing: Current Definitions

Research examining teacher wellbeing as an educational and psychological phenomenon has grown over the past decade, but there is no clear consensus on a definition of teacher wellbeing (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Hall and Taxer2019; Willis & Grainger, Reference Willis and Grainger2020). Arguably, the most comprehensive conceptualisation of teacher wellbeing comes from the recent Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) whitepaper (Viac & Fraser, Reference Viac and Fraser2020). Using the suggested framework, we examine how definitions of teacher wellbeing in the SE context have been proposed and offer a definition of SETWB, using the theory of occupational wellbeing.

Drawing upon Warr’s (Reference Warr1994) perspective, van Horn et al. (Reference van Horn, Taris, Schaufeli and Schreurs2004) formulated a comprehensive five-dimensional model encompassing affective, professional, social, cognitive, and psychosomatic dimensions of teacher occupational wellbeing. Van Horn et al. (Reference van Horn, Taris, Schaufeli and Schreurs2004) recognised the multidimensional synchronicity of teacher wellbeing to general wellbeing in that it comprises factors more than affect. This notion of wellbeing is consistent with the World Health Organization (2021) definition of wellbeing as a positively experienced state encompassing quality of life and sense of purpose.

In the OECD whitepaper on teacher wellbeing, Viac and Fraser (Reference Viac and Fraser2020), advocate a conceptual framework with four key components of teacher wellbeing that mirror the occupational model proposed by van Horn et al. (Reference van Horn, Taris, Schaufeli and Schreurs2004):

-

physical and mental wellbeing

-

cognitive wellbeing

-

subjective wellbeing

-

social wellbeing.

Of these factors, physical and mental wellbeing are stated as being present without psychosomatic complaints and stress-related symptoms. Although mental and physical wellbeing align with van Horn et al.’s (Reference van Horn, Taris, Schaufeli and Schreurs2004) occupational wellbeing model, other more affective dimensions may have a greater impact. Positively stated affective dimensions of wellbeing appear as cognitive, subjective and social wellbeing within the OECD framework (Viac & Fraser, Reference Viac and Fraser2020). Subjective wellbeing encompasses the positive feelings of satisfaction and purpose teaching provides. Social wellbeing refers to positive feelings that teachers have toward their relationships and the support received. Cognitive wellbeing, according to the OECD framework, is directly related to teacher efficacy in classroom management, instruction and engagement.

Experimental items to assess each component were included in the Programme for International Student Assessment – Teacher Questionnaire (PISA-TQ) 2021 questionnaire (postponed until 2022 due to the pandemic; Viac & Fraser, Reference Viac and Fraser2020). Although the nationally representative samples may provide robust empirical data, this latest dataset might maintain previous conventions, not collecting teacher demographic data based on subject or specialisation, limiting the opportunity to utilise PISA data to reliably inform direction for SETWB.

Special Education Teacher Wellbeing

The recent study by Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Chen, Lang, Kong and Qu2023) is most aligned with the OECD teacher wellbeing model, with wellbeing defined as a concept encompassing emotions, thoughts, intrinsic and extrinsic rewards, behaviours, and self-assessed physical and mental health. This was the only study that employed a wellbeing framework specifically addressing impacts of physical and mental health on SETWB. Van Horn et al. (Reference van Horn, Taris, Schaufeli and Schreurs2004) emphasise the challenges of using a broad model of wellbeing that includes deficit constructs such as mental health or life satisfaction, as wellbeing is not solely defined by the absence of these factors. Similarly, Olagunju et al. (Reference Olagunju, Akinola, Fadipe, Jagun, Olagunju, Akinola, Ogunnubi, Olusile, Oluyemi and Chaimowitz2021) implied absence or reduction of psychological burden and distress as definers of SETWB. This discourse is also found in literature focused on stress and burnout (Fox et al., Reference Fox, Tuckwiller, Kutscher and Walter2020; Hester et al., Reference Hester, Bridges and Rollins2020; Womack & Monteiro, Reference Womack and Monteiro2023). Cooke et al. (Reference Cooke, Melchert and Connor2016) suggested stress and burnout could be considered a construct whereby an absence of negative causational factors results in higher levels of wellbeing. Sharrocks (Reference Sharrocks2014) further warned against psychopathologising teachers instead of forming systematic understanding of wellbeing and promoting wellbeing-enhancing initiatives.

In contrast, Olagunju et al. (Reference Olagunju, Akinola, Fadipe, Jagun, Olagunju, Akinola, Ogunnubi, Olusile, Oluyemi and Chaimowitz2021) and Rae et al. (Reference Rae, Cowell and Field2017) did not offer explicit definitions of teacher wellbeing. A close synthesis of these articles elicited an understanding of the authors’ views of teacher wellbeing. The lack of concrete definitions is the only similarity as these research groups take distinct pathways exploring components of SETWB. Rae et al. (Reference Rae, Cowell and Field2017) proposed emotional literacy as key to increased teacher wellbeing and circuitously described wellbeing as a subjective construct where teachers do their best in a nurturing environment, surrounded by emotionally literate colleagues with embedded opportunities to reflect upon emotions. Holzner and Gaunt’s (Reference Holzner and Gaunt2023) ecological model suggested that incongruence between educational systems and teachers can impact their social, cognitive, physical and spiritual wellbeing. Viac and Fraser (Reference Viac and Fraser2020) concur and offer direction for working conditions that best support teachers’ occupational wellbeing. Job demands, including learning environments, workload, roles, classroom composition, disciplinary climate, performance evaluation, and resources, including autonomy, professional development, feedback and social support, are key components of a new teacher-specific framework (Cazes et al., Reference Cazes, Hijzen and Saint-Martin2015).

Fox et al. (Reference Fox, Tuckwiller, Kutscher and Walter2020) offer a holistic description of SETWB incorporating prior conceptualisations from Aelterman et al. (Reference Aelterman, Engels, Van Petegem and Pierre Verhaeghe2007) and Acton and Glasgow (Reference Acton and Glasgow2015) where wellbeing involves a balance of personal needs and environmental factors, resulting in purposefulness and satisfaction. Acton and Glasgow (Reference Acton and Glasgow2015) state that although there are a host of teacher wellbeing definitions in the literature, there is a lack of examining teachers’ lived experiences to define wellbeing.

Although researchers differ on a concrete definition of SETWB, what is consistent is that

-

wellbeing is largely a subjective construct with objective measurables;

-

teachers flourish in an environment where

-

■ the challenges of being a teacher are understood and met with support, and

-

■ further learning opportunities are provided and negative factors are minimised and do not outweigh the positive factors of being an SE teacher.

-

As such, the authors propose the following definition of SETWB: SE teacher occupational wellbeing is best described as a positive affect state where teachers feel supported individually and structurally to meet the contextual demands of special education.

The Work of Special Education Teachers

In Australia, there is a distinct difference between the wellbeing of teachers working in remote and metropolitan schools (Willis & Grainger, Reference Willis and Grainger2020). The geographical separation mirrors the separation of SE teachers from their mainstream colleagues, even within the same school. The job of an SE teacher has different roles and requirements (Billingsley & Cross, Reference Billingsley and Cross1992; Kauffman et al., Reference Kauffman, Felder, Ahrbeck, Badar and Schneiders2018; Nilsen, Reference Nilsen2017), yet the implications of these differences remain underresearched in relation to SETWB.

Research-identified challenges of an SE teacher include managing complex student disability (often with poor prognosis), dealing with paraprofessionals and specialists, creating and implementing individual education programs, adaptation of (often unsuitable) curriculum and teaching materials, and an emotional expenditure that is not commensurate with teaching experience or initial teacher education (Acton & Glasgow, Reference Acton and Glasgow2015; Billingsley & Cross, Reference Billingsley and Cross1992; Brunsting et al., Reference Brunsting, Sreckovic and Lane2014). Preston and Spooner-Lane (Reference Preston and Spooner-Lane2019) suggest that SE teachers are impacted by an absence of contextually appropriate professional development, lack of organisational support, and excessive expectation for students with complex medical, behavioural and mental health challenges to meet scholastic milestones.

In NSW, SE teachers may work in a variety of educational settings, such as Schools for Specific Purposes (SSPs), support classes in mainstream primary and high schools, itinerant support teachers (ISTs) or as mainstream teachers. SSPs offer specialised, intensive support in a dedicated setting for students with diverse needs and include hospital schools, tutorial centres and suspension centres (NSW Department of Education [DoE], 2023c). Support classes are limited in availability and can be found in select primary schools, high schools, and central schools throughout NSW. They offer specialised supports for students who are eligible and have been diagnosed with intellectual or physical disabilities, autism spectrum disorder, mental health conditions, sensory processing disorders, or behaviour disorders (NSW DoE, 2023b). ISTs are non-classroom teaching positions. ISTs collaborate with students, parents, classroom teachers, the school’s learning and support team, and other support agencies to create personalised plans for students with disability or experiencing difficulty at school and include trained teachers with specialisations in hearing and vision (NSW DoE, 2023a).

Supporting the call for further understanding of contextual roles of SE teachers and occupational wellbeing impacting and enabling factors is the contrast in roles of SE teachers between Australian states. Tasmanian SE teacher roles are more closely aligned with NSW non-classroom-based ISTs (Holzner & Gaunt, Reference Holzner and Gaunt2023), suggesting that, although the conceptualisation of SETWB may be similar, contextually specific needs would differ.

A direct connection exists between SE teaching and other caring professions, such as nursing, psychology, and social work, which are all subject to compassion fatigue (Gupta, Reference Gupta2020; Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Palladino and Barnett2007; Koenig et al., Reference Koenig, Rodger and Specht2018). The work of SE teachers requires intensive face-to-face interactions, use of evidence-based remedial learning approaches and managing complex disability (Holzner & Gaunt, Reference Holzner and Gaunt2023; Olagunju et al., Reference Olagunju, Akinola, Fadipe, Jagun, Olagunju, Akinola, Ogunnubi, Olusile, Oluyemi and Chaimowitz2021). Unparalleled pressure applied to teachers in Australia, and globally, during the pandemic has exacerbated these issues (Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Koehler, Cruickshank, Rogers and Stanley2023). Fray et al. (Reference Fray, Jaremus, Gore, Miller and Harris2023) highlight the emotional toll this disruption had on NSW teachers’ wellbeing, reporting teachers felt replaceable and unappreciated while workload increased and isolation persisted.

The ‘emotional labour’ (Rae et al., Reference Rae, Cowell and Field2017) of educating students, who often have comorbid mental health issues, is far greater for SE teachers whose responsibility it is to teach these students, often after they have experienced challenges in regular educational settings (Rae et al., Reference Rae, Cowell and Field2017). SE teachers are expected to take responsibility for individual management of students with complex medical, behavioural and disability-specific needs, and often lack specific medical or psychological training themselves, resulting in compassion fatigue and low self-efficacy (Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Palladino and Barnett2007; Holzner & Gaunt, Reference Holzner and Gaunt2023; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Chen, Lang, Kong and Qu2023). Their role is complex, multifaceted and requires specific skills and training. Further empirical research to elucidate the differences between contextual variables impacting SE and mainstream teacher wellbeing — given their unique contexts — is warranted and currently being undertaken by the authors.

Factors That Promote and Impact Special Education Teacher Wellbeing

A search of empirical literature from 2010 to present, including both wellbeing (or well-being) and special education teacher in the title or abstract, identified (just) five articles, with only one on Australian SE teachers. The search strategy used A+ Education, Sage, EBSCO, ProQuest databases and Google Scholar. Results defining wellbeing as a separate and distinct phenomenon or comparing teacher wellbeing were included.

Table 1 summarises negatively impacting and positively promoting factors identified through the literature search. It should be noted that several negatively impacting factors have corresponding positively promoting factors.

Table 1. Negative and Positive Factors Affecting Special Education Teacher Wellbeing (SETWB)

We suggest these factors can be grouped into four categories that SE teachers perceive as beneficial to their wellbeing, which then align with aspects of the OECD teacher wellbeing framework (see Table 2).

Table 2. Special Education Teacher Wellbeing (SETWB) Factors Aligned to OECD Wellbeing Framework

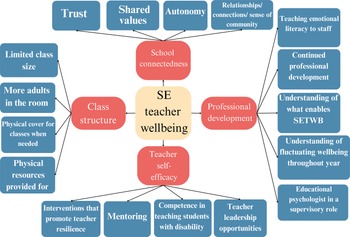

These promoters of SETWB are arguably more important than negatively stated impacting factors such as workload burden (Rae et al., Reference Rae, Cowell and Field2017), teaching students with disability or students with complex and challenging behaviour (Olagunju et al., Reference Olagunju, Akinola, Fadipe, Jagun, Olagunju, Akinola, Ogunnubi, Olusile, Oluyemi and Chaimowitz2021; Rae et al., Reference Rae, Cowell and Field2017) and balancing multiple roles (Fox et al., Reference Fox, Tuckwiller, Kutscher and Walter2020). Using this framework allows for a conceptual model of relationships (Figure 2) to be drawn between positive enabling factors that have emerged through the literature and the identified categories.

Figure 2. A Conceptual Model of Positive Special Education Teacher Wellbeing (SETWB) Factors.

School connectedness

School connectedness, sometimes referred to in the literature as belonging, refers to feelings of being supported and having positive relationships at school (Mankin et al., Reference Mankin, von der Embse, Renshaw and Ryan2018; Renshaw et al., Reference Renshaw, Long and Cook2015). This psychosocial phenomenon has been positively correlated with higher levels of teacher wellbeing and negatively correlated with decreased motivation and teacher retention in the teacher wellbeing literature (Collie & Carroll, Reference Collie and Carroll2023; Dreer, Reference Dreer2023; Fox et al., Reference Fox, Walter and Ball2023).

McCallum et al. (Reference McCallum, Price, Graham and Morrison2017) espouse that student interactions, support from leadership, and collaborations with parents are a correlational link between teacher occupational wellbeing and school connectedness. The importance of connectedness was previously elucidated by Acton and Glasgow (Reference Acton and Glasgow2015), who listed collegiality, trust, and values as predominant factors promoting wellbeing. They elaborated their view that current school operational systems in Australia silence teacher voice and undervalue horizontal leadership styles they describe as essential building blocks to teacher wellbeing. Viac and Fraser (Reference Viac and Fraser2020) offer a different understanding of school connectedness focusing on student–teacher relationships, supportive school culture and positive organisational climate, with specific mention of trust between school leaders and teachers.

Fox et al. (Reference Fox, Tuckwiller, Kutscher and Walter2020) used the Teacher Subjective Wellbeing Questionnaire to measure school connectedness. Although school connectedness levels remained constant over a school year, interviews with SE teachers revealed being trusted by senior leaders and administrators, and not having excessive input from parents, were important for increased wellbeing. Supporting the professional and emotional needs of teachers, Grant (Reference Grant2017) advocates positive leadership practices, such as teacher autonomy and constructive feedback, as critical in retaining teachers in complex schools.

According to Wessels and Wood (Reference Wessels and Wood2019), schools should prioritise physical spaces that promote teacher connectedness. Page et al. (Reference Page, Anderson and Charteris2021) highlighted the importance of spaces in SE, identifying a link between dedicated spaces for collegiality and a stronger sense of belonging.

Holzner and Gaunt (Reference Holzner and Gaunt2023) found Tasmanian SE teachers would like wellbeing-specific initiatives to be systematically supported, suggesting professional learning communities as a connection-building space. There is an ongoing debate about why SE teachers in Australia are still physically and pedagogically separated from their mainstream colleagues (Passeka & Somerton, Reference Passeka and Somerton2022; Thorius, Reference Thorius2016). This presents an opportunity to explore initiatives and factors that can promote school connectedness for SE teachers.

Teacher self-efficacy

Using Bandura’s cognitive theory model, Viac and Fraser (Reference Viac and Fraser2020) suggest teacher self-efficacy is a subjective measure of one’s belief in their ability to succeed and perform particular behaviours; thus, teacher self-efficacy could be conceptualised as self-belief regarding capacity to perform in adversity. If teachers have high self-belief about mastering the multidimensional components of teaching, it is possible to increase wellbeing (Kouhsari et al., Reference Kouhsari, Chen and Baniasad2023; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, Reference Skaalvik and Skaalvik2007; Zee & Koomen, Reference Zee and Koomen2016).

Being able to shape student learning and behaviour has been positively associated with SE teacher levels of job satisfaction and inversely correlated with burnout and stress (Turner et al., Reference Turner, Thielking and Prochazka2022; Viel-Ruma et al., Reference Viel-Ruma, Houchins, Jolivette and Benson2010; Womack & Monteiro, Reference Womack and Monteiro2023). Teachers with high self-efficacy are able to meet challenges within the school context, including catering for students with disability (Collie et al., Reference Collie, Malmberg, Martin, Sammons and Morin2020; Kingsford-Smith et al., Reference Kingsford-Smith, Collie, Loughland and Nguyen2023). It has also been argued that autonomy is an element of teacher capacity to reflexively carry out their role to the best of their ability (Collie & Carroll, Reference Collie and Carroll2023; Kaynak, Reference Kaynak2020; Olsen & Mason, Reference Olsen and Mason2023; Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2020).

Feelings of confidence are gained via teaching experience and willingness to try new teaching methods, gain feedback and consolidate knowledge. Post hoc comparison showed SE teachers with more than 15 years of experience scored significantly higher in teacher self-efficacy than those with 1–5 years of experience (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Chen, Lang, Kong and Qu2023). SE teachers with less experience are at greater risk of leaving the profession than those with more experience (Billingsley & Bettini, Reference Billingsley and Bettini2019). In contrast, Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Chen, Lang, Kong and Qu2023) found occupational wellbeing was not significantly correlated to years of teaching, F(2, 223) = 1.855, p = 0.159.

Self-efficacy is pivotal for SETWB yet underrepresented within the research. Viac and Fraser (Reference Viac and Fraser2020) define measurement of teacher self-efficacy on three separate scales: classroom management efficacy, instructional efficacy, and student interaction efficacy. Operationalising these measures of teacher self-efficacy should be considered for further empirical study of SETWB.

Professional development

Teacher professional development is critical to transforming classroom practice, strengthening schools, and increasing student learning outcomes (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership, 2018; OECD, 2019). Professional development with an emphasis on curriculum, school administration or human resources has long been the focus of attention within education (Wessels & Wood, Reference Wessels and Wood2019). Prominent within existing literature is the significance of deliberately fostering and enhancing the capacity of SE teachers and accompanying systems to effectively identify and acknowledge distinct emotional intricacies inherent in their profession (Olagunju et al., Reference Olagunju, Akinola, Fadipe, Jagun, Olagunju, Akinola, Ogunnubi, Olusile, Oluyemi and Chaimowitz2021; Platsidou & Agaliotis, Reference Platsidou and Agaliotis2017; Rae et al., Reference Rae, Cowell and Field2017; Womack & Monteiro, Reference Womack and Monteiro2023; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Chen, Lang, Kong and Qu2023).

Rae et al. (Reference Rae, Cowell and Field2017) proposed educating SE teachers on emotional literacy, with the goal of fostering successful teacher–pupil relationships in all areas of learning. The study was inspired by a supervision model commonly observed in health professions where practitioners have regular individual or small group meetings to discuss complex or challenging situations. Rae et al. (Reference Rae, Cowell and Field2017) found teachers expressed a desire for regular opportunities to participate in objective, solutions-focused sessions with an educational psychologist, and establishment of effective whole-school systems was crucial for this to happen.

Thematic analysis highlighted the need for ongoing professional development in emotional self-management for staff, surpassing limited impact of one-time learning sessions. Spence (Reference Spence2015) concurs, starting with a rather catchy title: ‘If You Build It They May NOT Come … Because It’s Not What They Really Need!’. Spence suggests wellbeing programs in Australian private and government sectors are missing the mark due to a lack of understanding of contextual needs. Holzner and Gaunt (Reference Holzner and Gaunt2023) suggest SE teachers’ needs should be driving professional development, highlighting the crucial voice of educators.

Class structure

The literature concerning SETWB has provided findings on how SE class structures promote wellbeing (Jennings & Greenberg, Reference Jennings and Greenberg2009; Mankin et al., Reference Mankin, von der Embse, Renshaw and Ryan2018; Sorensen & Ladd, Reference Sorensen and Ladd2020). One study found the limited size of SE classes promoted wellbeing as it allowed greater individualised instruction and moments to build meaningful rapport with students (Rae et al., Reference Rae, Cowell and Field2017). Having fewer pupils in class, having another adult in the room, and being able to provide necessary educational attention to students all promoted increased levels of SETWB (Rae et al., Reference Rae, Cowell and Field2017). This premise could also be linked to teacher self-efficacy, as teachers felt they were best able to meet outcomes plus work in the best interests of students (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Manchanda and Greenstein2021). The purported impact of smaller class sizes is mirrored in the broader literature, where limited class sizes increased teacher effectiveness via greater instructional individualisation while decreasing adverse student behaviour impacts (Fray et al., Reference Fray, Jaremus, Gore, Miller and Harris2023; Garrick et al., Reference Garrick, Mak, Cathcart, Winwood, Bakker and Lushington2017). Olagunju et al. (Reference Olagunju, Akinola, Fadipe, Jagun, Olagunju, Akinola, Ogunnubi, Olusile, Oluyemi and Chaimowitz2021) briefly touch on this supposition, suggesting it may be a contributing factor in lower levels of reported psychological burden for SE teachers in Nigeria, who have mainstream classes of up to 51 students, with an average of 40. A positive contributor to wellbeing was when a school was able to relieve the classroom teacher from class if they were experiencing heightened emotions or needed to complete incident paperwork after a physical altercation between students or a student needed to be physically restrained (Rae et al., Reference Rae, Cowell and Field2017).

These synthesised emergent factors provide a collective from which further empirical research can build. Through empirical research and scientific measurement, we can track SETWB changes and enact informed policies that support suggested differential needs of SE teachers.

Conclusion

The wellbeing of SE teachers is a decisive factor in the retention, and mental health, of quality educators in this high-growth and specialised discipline. When teachers have strong school connection and self-efficacy, are provided meaningful professional development, and work in an environment with leaders who understand their specialised work, wellbeing thrives.

In Australia, the number of students with identified disability continues to rise, with recent data suggesting most students with disability attend mainstream schools, and 12% attend an SSP (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2022). Students attending mainstream support units in NSW DoE schools have increased 36% between 2011 and 2020, compared to 1.6% for mainstream students (NSW Department of Education and Communities, 2013; NSW DoE, 2021). A 2023 Teacher Education Expert Panel report commissioned by the Australian Government recognised the increased need for teachers with specialised knowledge in educating students with disability. The report suggested initial teacher education programs include specific SE courses and access for beginning teachers to higher education providers, plus ongoing mentoring — all only possible if quality SE teachers are retained.

This article highlights the paucity of research concerning SETWB globally. As discussed, the work of an SE teacher is different from that of a mainstream teacher, and existing research suggests there are factors requiring further empirical exploration of conceptions of wellbeing beyond the absence of stress and burnout. The OECD teacher wellbeing framework offers opportunity for conceptual consistency in addressing this gap through localised research, acknowledging contextual diversity of SE teaching. Our findings point to more relevant professional development, ensuring systems promote teacher self-efficacy and autonomy through meaningful connection and ratifying the diversity and differences of SE teachers’ work.

Our call is for a greater emphasis on research to deepen our understanding of the key factors influencing SETWB and of SE teachers’ unique lived experience perspectives.