1. INTRODUCTION

What Though the Field Be Lost? All is not Lost.Footnote 1

International declarations and institutions call for judicial specialization, envisaging expert courts and judges and lawyers trained in environmental matters to advance the environmental rule of law and promote sustainable development.Footnote 2 Specialist environment courts and tribunals are better positioned than general courts to develop innovative remedies and holistic solutions to environmental problems by embracing a flexible mechanism for dispute resolution.Footnote 3 In this context, India’s commitment to a “green court” assumes significant practical importance. The National Green Tribunal of India (NGT) was established by statute in 2010.Footnote 4 Subsequently, the NGT acquired a national and international reputation based upon its progressive, innovative environmental decisions that reach far beyond the courtroom door. The judicial membership of the NGT comprises legal and scientific experts—a composition unique within India. It has resulted in a symbiotic, dynamic community of decision-makers employing a vigorous, flexible court process that offers swift, affordable, and open public access through the widest possible interpretation of who is an aggrieved party.

The widespread recognition of this bold, innovative tribunal is fulsome and positive. It stands as an exemplar for developing nations. Pring and Pring describe the NGT in their path-breaking publication on courts and environmental tribunals as “incorporating a number of best practices … and has become a major arbiter of some of the most pivotal environmental battles in India.”Footnote 5 They subsequently stated “the NGT has successfully expanded its openness, procedural flexibility, transparency and progressive judgments.”Footnote 6 Lord Carnwath of Notting Hill, Judge of the Supreme Court UK, observed the tribunal as “raising awareness and a sense of environmental responsibility in the government, local and national, and the public.”Footnote 7 Chief Justice Brian Preston, Land and Environment Court of NSW Australia, wrote “the NGT is an example of a specialized court to better achieve the goals of ensuring access to justice, upholding the rule of law and promoting good governance.”Footnote 8 Judge Michael Hantke Domas, Chief Justice of the Third Environmental Court Chile, focused on the novelty and boldness of the NGT. According to Domas J., “as a new player in the Indian judicial panorama, the NGT was strongly led by knowledgeable and valorous judges, who were fit to answer justice demands of the people represented by equally qualified and tenacious lawyers.”Footnote 9 Judge Michael Rackemann of the Queensland Planning and Environmental Court considered “the NGT adopts a robust and expansionist approach to the interpretation of its jurisdiction and powers.”Footnote 10 Academic experts including Warnock described the NGT as follows: “the NGT is one of the world’s most progressive Tribunals … the procedures adopted, powers assumed, and remedies employed by the NGT are notable.”Footnote 11 Ryall stated:

the emergence of the NGT, its contemporary jurisprudence and impact on Indian society provide important insights for anyone interested in environmental governance and regulation … the NGT is held in high esteem and enjoys a strong degree of public confidence.Footnote 12

Similar views have been expressed in India. The Vice President of India, M. Venkaiah Naidu, applauded the tribunal by stating “the efforts and involvement of the NGT in dispensation of environmental justice, evolving environmental jurisprudence, promoting discourse and spreading awareness are commendable … all stakeholders stand united and miss no opportunity to join hands for the same.”Footnote 13 Prakash Javadekar, Minister for Human Resource Development, in a similar vein stated “the NGT has been responsible for expeditious dispensation of environmental justice in our country, thus, satisfying legislative intent behind its enactment.”Footnote 14 Judge Rajan Gogoi of the Supreme Court of India observed “Its [NGT] advent marks another rendition of India’s green revolution … with the passage of time the NGT has become one of the foremost environmental courts globally with a wide and comprehensive jurisdiction.”Footnote 15 Ritwick Dutta, a leading environmental barrister, stated “the Green Tribunal is now the epicentre of the environmental movement in India …. It has become the first and last recourse for people.”Footnote 16 Fieldwork undertaken at the NGT involving interviews with lawyers and litigants appearing before the tribunal reinforce the professional and public assessment of the value and appreciation of the strength of the NGT.Footnote 17 A young lawyer who appears before the NGT described it: “a bench of this kind with an expert member is creating new environmental jurisprudence. The expert members help young lawyers understand environmental issues.”Footnote 18 Three litigants summarized their experiences before the NGT as “our experience has been tremendous in the NGT benches. We are attending the case in person and have been here three to five times. The NGT is a life saver. The NGT has given us justice.”Footnote 19

Nevertheless, these national and international commendations of the NGT tell but part of the story of the tribunal. The tribunal has been subject to criticism at the national level from key affected parties. For instance, “officials speak about the Tribunal’s clamour to get more powers and perks. They call it a ‘power-hungry institution’ that has failed the purpose for which it was created.”Footnote 20 The NGT has been accused of overstepping its jurisdiction by not following the provisions of the NGT Act 2010, resulting in embarrassment to the government before Parliament.Footnote 21 Again, the NGT’s orders have been considered as a case of judicial overreach, as they disturb the balance of power between the judiciary and the executive as envisaged in the Indian constitutional structure. For example, the NGT’s general order banning mining of sand without a requisite environmental clearance from the State Environment Impact Assessment Authority was considered as a case of judicial overreach by Manohar Parrikar, the Goa Chief Minister. According to Parrikar:

the order is a case of (judicial) overreach. Everyone knows the order is not implemented. It (the order) has resulted in rise of prices and black marketing of sand …. If you stop economic activity, we (Governments) will not have money to pay. We might also have to take a cut (from the illegal sand mining operation) …. Irrational and sudden bans order going across board should not be issued without hearing the State.Footnote 22

Similarly, the ministers and officials from the states of Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, and Manipur were of the view that sand-mining orders without prior clearance from the environment ministry across India was a case of not studying the situation in the north-eastern states.Footnote 23

There have emerged negative forces within India determined to contain or possibly close the tribunal. This is an account of two campaigns—one seeking to promote the NGT, the other constituting a restraining force. This article comprises four sections. It opened with a brief account of the current standing of the NGT in judicial and academic international and national communities. The second section presents the paper’s theoretical underpinning derived from social psychology and organizational management scholarship. It offers a practice-based, theoretical framework applicable to the NGT. The article employs a transmigration of theory and its application from one discipline to another social science: business psychology and management to law. In the third section, the history of the NGT is unpacked by identifying the principal actors or forces, both positive and negative, involved in the establishment, exercise, and review of the tribunal. Today, the NGT faces major challenges regarding its future survival because of external “restraining forces” seeking to downgrade its status and functionality. This section addresses this crisis, identifies and analyses the reasons and actions of those interested in supporting the NGT and, on the other hand, those who are concerned and challenged by its growth, activities, and popularity. This growing lobby constitutes a negative force seeking to restraint and even possibly close the NGT. This oppositional struggle process commenced in 2011 and continues to date. The conclusion reviews the relationship between theory and practice as played out in the life history of the NGT.

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK: THREE-STEP CHANGE MODEL AND FORCE-FIELD THEORY

Kurt Lewin (1890–Reference Lewin1947) is considered an influential physicist and psychologist and, for the purposes of this paper, the founding father of change management theory.Footnote 24 Lewin’s work on planned changeFootnote 25 provides an elaborate and robust approach to understanding and resolving social conflict, whether in an organization or wider society. As Edgar Schein commented:

The intellectual father of planned change is Kurt Lewin. His seminal work on leadership style and the experiments on planned change that sought to understand and change consumer behaviour launched a generation of research in group dynamics and the implementation of change programmes.Footnote 26

The relevance of Lewin’s work to fast-changing modern organizations continues to this day. Change management is defined as “the process of continually renewing an organization’s direction, structure, and capabilities to serve the ever-changing needs of external and internal customers.”Footnote 27 The academic literature on organizational change reflects consensus on two important matters. First, the pace of change is faster in the present economic and globalized environment.Footnote 28 Second, internal and external factors precipitate change and affect organizations.Footnote 29 Thus, change is “both pervasive and persistent and normality”Footnote 30 but simultaneously “reactive, discontinuous, ad hoc and often triggered by a situation of organisational crisis.”Footnote 31

Understanding organizational change requires an analysis of the “field as a whole,”Footnote 32 as it helps to analyze scientifically the pattern of forces operating in the group. “The process is but the epiphenomenon, the real object of the study is the constellation of forces.”Footnote 33 In this context, Lewin’s “three-step change model” and “field-force theory” are of foundational importance. There exists a body of lively, disparate opinion and literature about Lewin’s diluted and overly simplistic theories that are beyond the scope of this article.Footnote 34 For instance, Kanter claims that “Lewin’s … quaintly linear and static conception—the organisation as an ice cube—is so wildly inappropriate that it is difficult to see why it has not only survived but prospered.”Footnote 35 Nevertheless, Lewin’s contribution remains the quintessence of organizational change. It explores, assesses, and creates organizational realities to address and answer issues about resistance, barriers, and failure to change initiatives.Footnote 36

2.1 The Three-Step Change Model

Lewin’s “three-step change model” is considered as the bedrock of organizational change. Successful change according to Lewin includes three aspects: “unfreezing the present level … moving to the new level … and freezing group life on the new level.”Footnote 37

Figure 1 Kurt Lewin change model. Source: Lewin (Reference Lewin1947); Schein (Reference Schein2010)

Figure 2 Kurt Lewin force-field analysis.Source: Lewin (Reference Lewin1943)

Lewin also suggested that change at any level is determined by a force field thereby facilitating the movement of the organization to a new level of equilibrium.

Lewin’s basic paradigm (unfreeze–change–freeze) was elaborated and refined by Schein for a better understanding of the psychosocial dynamics of transformative organizational change.Footnote 38 In his 2010 work, Schein observed that the process of change entails creating the perception that the change is needed, then moving towards learning new concepts, and finally institutionalizing new concepts as a norm.Footnote 39

Accordingly, the first step is “unfreezing or creating a motivation to change. This requires the ‘group’ that is the target of change must unlearn something.”Footnote 40 Unfreezing involves three processes to develop motivation to change: (1) disconfirming data creating disequilibrium due to the organization’s inability to achieve its goals or its processes, thereby pointing out that “something is wrong somewhere”Footnote 41; (2) making the members of organization uncomfortable and anxious, implying “unless we change, something bad will happen to the individual, the group, and/or the organization”Footnote 42; and (3) psychological safety, in the sense of being able to see “the problem and learning something new”Footnote 43 by adopting a positive vision, team effort, and constructive support.

The second step is “cognitive redefinition” that lays the groundwork for making the change. Learning new concepts, expanding concepts with broader meaning and new standards of evaluation either through “imitating a role model … or scan our own environment and develop our own solutions,”Footnote 44 thereby moving to a new changed state. The mechanism works best when there is clarity about the goals to achieve and the new way of working.

The final step is “refreezing” wherein the new learning is reinforced and institutionalized for producing better confirmed actual results to fix the problems that launched the change programme.Footnote 45 The change has been made and the emphasis is on structures and procedures that help to maintain the changed behaviour in the system. Thus, to maintain the new change as permanent, institutional policies and procedures should encourage and reinforce the new behaviour until it becomes a habit.

The “three-step change model” (classic model) has become “far more fundamental and instrumental than Lewin ever intended … a solid foundation … hardened through series of interpretations … repress[ing] other ways of seeing or organising thinking about change.”Footnote 46 Lewin’s classic model has continuing relevance to contemporary organizations. Its application to an adjudicatory body such as the NGT is useful in understanding this new organizational reality—the NGT that seeks to promote sustainable development.

2.2 Force-Field Theory

Lewin’s pioneering work on force-field theory is often considered as the epitome of a change model providing the “theoretical underpinning of all his applied work.”Footnote 47 Field theory, through its scientific rigour and practical relevance, analyzes the changing behaviour of individuals through the operation of forces in life. As stated above, the force-field theory integrates with the classic model to bring about planned change at the individual, group, organization, or societal level.Footnote 48

According to Lewin, “change and constancy are relative concepts; group life is never without change, merely differences in the amount and type of change exist.”Footnote 49 The construct “force” characterized the direction and strength of tendency to change. He believed that the driving and “restraining forces” tend to cause the changes. The forces towards a positive side are the “driving forces,” whereas the “restraining forces” create physical or social obstacles:

“Driving forces”—corresponding, for instance, to ambition, goals, needs, or fears—are “forces towards” something … tend to bring a change … a “restraining force” is not in itself equivalent to a tendency to change; it merely opposes “driving forces.”Footnote 50

Where the forces are equal in magnitude, the status quo will be maintained.Footnote 51 However, “quasi-stationary equilibria can be changed by adding forces in the desired direction or diminishing opposing forces.”Footnote 52 Lewin recognized that forces shift quickly and radically under certain circumstances such as organizational or societal crisis, and thus lead to the loss of the status quo. “New patterns of activity can rapidly emerge, and a new behavioural equilibrium or ‘quasi-stationary equilibrium’ is formed.”Footnote 53

To understand the actual changes and its effect, it is important to examine the total circumstances and not merely one property. According to Lewin:

to change the level of velocity of a river its bed has to be narrowed or widened, rectified, cleared from rocks etc. … for changing a social equilibrium, too, one has to consider the total social field: the groups and subgroups involved, their relations, their value system etc.Footnote 54

To achieve successful change, the “driving forces” must always outweigh “restraining forces.” This provides support in moving through the unfreezing–learning–refreezing stages of change. For Lewin, the change was a slow learning process, the success of which depended on how individuals or groups understood and reflected on the forces that impinged on their lives.Footnote 55

The use of force-field theory is helpful to understand the change analysis insights that align with the current organizational environment of the NGT. The interplay of forces would help distinguish whether factors within and without the NGT are “driving forces” for change or “restraining forces” that work against desired change.

3. APPLICATION OF THEORY: THE NATIONAL GREEN TRIBUNAL

This section deals with the practical application of Kurt Lewin’s theory followed by Schein’s work that developed the three-step change model. The framework has been applied to various organizations, including the NHS,Footnote 56 the poor state of primary education in the state of Bihar, India,Footnote 57 gender,Footnote 58 and IT implementation.Footnote 59 However, this is the first time it has been applied to an Indian adjudicatory tribunal: the NGT.

In Lewin’s theory, the existence of an “organization” is central to understanding change. Academics have defined the term “organization” from different perspectives. These include adopting a professional categorization, as human labour, conscious human activity linking and co-ordinating all the production agents to achieve the optimum result of the work, or a scientific approach.Footnote 60 A definition by McGovern suggests that an organization is “an organised or cohesive group of people working together to achieve commonly agreed goals and objectives.”Footnote 61 Adopting McGovern’s definition, it is advanced here that the courts and tribunals are organizations within the “new public management (NPM)” paradigm.Footnote 62 The focus of NPM is on “quality,” namely “achieving the full potential that one is capable of with the resources one has”Footnote 63 with a “client-oriented approach.”Footnote 64 In the context of judicial organizations, “quality” in NPM includes the principles of effectiveness, efficiency, and transparency.Footnote 65 Factors including time, timeliness, competency, consistency, accessibility, accuracy, and responsiveness provide direction and help in assessing quality service in the judicial organization.Footnote 66 The fulfilment of quality requirements contributes towards the legitimization of judicial organizations towards the public and are compatible with values such as equity and equality.Footnote 67

The courts and tribunals in India are judicial organizations that guarantee the “quality” requirements for the effective delivery of justice. Specifically, the NGT is an “organization” consisting of legal and scientific experts who create a symbiotic relationship that operates collectively as joint decision-makers and adjudicators to dispense environmental justice. The overarching goal is contained in the Preamble of the NGT Act 2010. It aims for the effective and expeditious disposal of cases relating to environmental protection, conservation of forests and other natural resources, including enforcement of environmental legal rights, giving relief and compensation for damages to persons and property, and for matters connected or incidental. The NPM “quality” principles are reflected in the NGT’s measurable characteristics: participatory parity by giving a liberal and flexible interpretation in terms of “aggrieved party” (standing) to access environmental justiceFootnote 68; the availability of “resources to enable participation” through low feesFootnote 69; the ability both to fast-track and decide cases within six months of application or appealFootnote 70; and application of the sustainable development, precautionary, and polluter-pays principles when passing any order, decision, or award for effective implementation of environmental rights and duties in India.Footnote 71

In this context, I apply Lewin’s model of organizational change to the NGT. Comprehending the kinetics of Lewin’s force-field theory is vital in learning to apply his “three-step change” in practical situations.

3.1 Unfreeze

Unfreezing the old behaviour to learn something new provides motivation to change. The focus is to address underlying problems and initiate diagnostic work to accept new learning and reject old or dysfunctional behaviour.

The unfreezing was triggered by strong “driving forces,” being the Supreme Court of India and the Indian Law Commission. They identified problems and challenges relating to environmental adjudication and dispensation of environmental justice in India. The perceived accepted need within these institutions to “unlearn and learn something new” was powerful.

The Supreme Court of India was the initial primary external driving force behind the initial unfreezing or motivation-to-change process. The Supreme Court’s intervention was based on its twofold concern. First was the complexity and uncertainty underpinning the scientific environmental evidence presented in court. The Supreme Court was conscious that complete scientific certainty is the exception, not the norm. Uncertainty, resulting from inadequate data, ignorance, and indeterminacy, is inherent in science.Footnote 72 The court was aware of the scientific limitations of the judiciary in environmental cases where science should undertake a key function. The involvement of independent qualified scientists sitting as equals with judicial members would go some way to ameliorating the above concerns. Second, there is an ossified litigious legal system that challenges and possibly surpasses the court delays described in Jardine v. Jardine in Dickens’s Bleak House. Delay is not a recent phenomenon and can be traced back to the time of the Raj. It is a result of court clogging, adjournments, missing papers, absent witnesses, and conscious delaying tactics by both lawyers and the parties.Footnote 73

In M. C. Mehta v. Union of India,Footnote 74 the Supreme Court advocated the establishment of environmental courts, stating:

we would also suggest to the Government of India that since cases involving issues of environmental pollution, ecological destruction and conflicts over national resources are increasingly coming up for adjudication and these cases involve assessment and evolution of scientific and technical data, it might be desirable to set up environment courts on a regional basis with one professional judge and two experts, keeping in view the expertise required for such adjudication. There would be a right to appeal to this court from the decision of the environment court.Footnote 75

The proposal to establish environmental courts was supported by two subsequent cases: Indian Council for Enviro- Legal Action v. Union of India Footnote 76 and AP Pollution Control Board v. M. V. Nayudu.Footnote 77 The court suggested an environmental court would benefit from the expert advice of environmental scientists and technically qualified persons as part of the judicial process. There was a further recommendation that the Law Commission of India should examine the matter of establishing an environmental court.

In the Indian Council for Enviro-Legal Action case,Footnote 78 the Supreme Court highlighted the issue of delay. Cases are lodged within a system already groaning under the weight of its case-load. The court, aware of the existence of other specialized tribunals, for example in consumer-protection law, seized the opportunity to highlight the importance of specialized environmental courts, stating:

The suggestion for the establishment of environment courts is a commendable one. The experience shows that the prosecutions launched in ordinary criminal courts under the provisions of Water Act, Air Act and Environment Act never reach their conclusion either because of the workload in those courts or because there is no proper appreciation of the significance of the environment matters on the part of those in charge of conducting those cases. Moreover, any orders passed by the authorities under Water, Air or Environment Acts are immediately questioned by the industries in courts. Those proceedings take years and years to reach conclusion. Very often, interim orders are granted meanwhile which effectively disable the authorities from ensuring the implementation of their orders. All these point to the need for creating environment courts which alone should be empowered to deal with all matters, civil and criminal, relating to the environment.Footnote 79

The interventions and dicta by the Supreme Court during this period were also influenced by the non-implementation and non-operation of two statutes that supported the creation of a specialized environmental tribunal. These were the National Environment Tribunal (NET) Act 1995 and the National Environmental Appellate Authority (NEAA) Act 1997.

The NET Act 1995 provided strict liability for damages arising out of any accident occurring while handling any hazardous substance and for the establishment of a tribunal for effective and expeditious disposal of cases arising from such accidents with a view to giving relief and compensation for damages to person, property, and the environment. The composition of the tribunal consisted of a chairperson with membership including vice-chairpersons, judicial members, and technical members as the central government deemed fit. Unfortunately, it was not notified “due to the sheer neglect and/or lack of political will to take the risk on the part of the executive to pave the way for the establishment of such a specialized environment Tribunal.”Footnote 80 The environment tribunal was not constituted.

Subsequently, the NEAA Act 1997 provided for the establishment of the NEAA to hear appeals with respect to restriction of areas in which any industries, operations, or processes shall be carried out or not subject to safeguards under the Environmental (Protection) Act 1986. Expertise or experience in administrative, legal, management, or technical aspects of problems relating to environmental management law, planning, and development were essential qualifications for persons to be appointed to the NEAA. The NEAA was established on 9 April 1997 to address grievances regarding the process of environmental clearance and implement the precautionary and polluter-pays principles.Footnote 81 However, the NEAA did little work because its role was limited to the examination of complaints regarding environmental clearances. After the first chairperson’s term expired, no replacement appointment was made.Footnote 82 In Vimal Bhai v. Union of India High Court of Delhi,Footnote 83 the court expressed concern that the government was unable to find qualified members to fill positions in the NEAA. The posts of chairperson and vice-chairperson remained vacant from July 2000 until the 1997 Act was repealed by the National Green Tribunal (NGT) Act 2010.Footnote 84 Thus, the NEAA was closed.

Following the powerful observations made by the Supreme Court, the Law Commission, an active and influential participant in legal reform in India, became a strong organizational driving force to motivate change through the establishment of “environment courts.”Footnote 85 The Law Commission examined the questions by reviewing the technical and scientific problems that arise before courts and observed:

it is clear that the opinions as to science which may be placed before the Court keep the judge always guessing whether to accept the fears expressed by an affected party or to accept the assurances given by a polluter.Footnote 86

The Law Commission was persuaded that, in seeking a balanced, informed decision in such cases, “environmental courts” with scientific as well as legal inputs would be better placed to reach a determination. Such courts could have wide powers to make on-the-spot inspections and hear oral evidence from resident panels of environmental scientists. In addition, it was suggested that the establishment of environmental courts would reduce the burden on the High Courts and Supreme Court, often involving complex and technical environmental issues, thereby providing accessible and speedy justice.Footnote 87

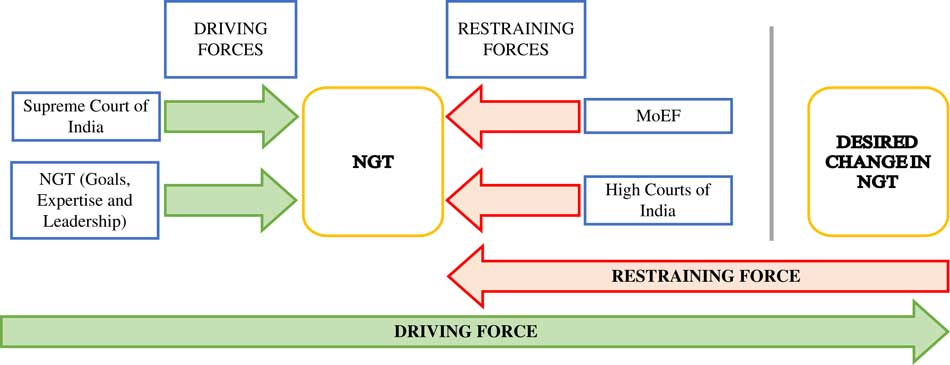

At that time, the weaker “restraining force” to the Supreme Court and Law Commission of India was the Government of India. The government proposed a centralized Appellate Authority based in Delhi to hear appeals over the statutory authority, namely the Water Act, 1974, the Air Act, 1981, and the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986.Footnote 88 The proposal did not contain provisions for technical or scientific inputs in the centralized Appellate Authority. Figure 3 illustrates the effect of field-forces regarding the NGT.

Figure 3 Initial dominant driving forces. Source: Author

Initially, the “driving forces” outweighed the “restraining forces,” thereby triggering a change from the present level to the desired one. Thus, the first step of “unfreezing” witnessed the “driving forces” advocating a change that would shape the future of environmental justice in India.

3.2 New Learning and Change

After an organization is unfrozen, the forces effect a change that reflects “new learning” and moving to a new state. For Lewin, the term learning “refers [ed] in a more or less vague way to some kind of betterment … and a multitude of different phenomenon.”Footnote 89 In an organizational set-up, “new learning” reflects “cognitive redefinition” comprising (1) learning new concepts; (2) learning new meaning for old concepts; and (3) adopting new standards of evaluation.Footnote 90 The two mechanisms that help “new learning” are either through imitation and identification with a role model or scanning the environment.Footnote 91 Imitation and identification work best when there is clarity about the new concept and way of working. Scanning the environment works through trial and error and developing own solutions until something works.Footnote 92

3.2.1 Learning New Concepts

In India, the “new learning” stage witnessed the involvement of both the external and internal “driving forces” influenced by the societal needs, values, and hopes, and the long-term development of Indian environmental justice discourse. The specialized NGT as a learning new concept following the strong judicial pronouncements and recommendations of the powerful Law Commission of India was the first step towards “new learning.”Footnote 93

The NGT as a specialized body equipped with necessary expertise to handle environmental disputes involving multidisciplinary issues became a forum offering greater plurality for environmental justice. As a learning new concept, it was guided by imitation and identification with a role-model mechanism that embraced the need for specialized tribunals with technical expertise to provide environmental justice.

The external “driving forces” to introduce “change” were first triggered by the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF).Footnote 94 It is important to note that the MoEF acted as a driving force between 2009 and 2011. After 2011, it became a strong restraining force. The reason for this reversal was the replacement of the progressive Minister for MoEF (see Figure 4).

Figure 4 MoEF as a driving force (2009–11). Source: Author

The Government of India through the MoEF introduced the NGT Bill 2009 in the Lower House (Lok Sabha) of the Indian Parliament on 31 July 2009.Footnote 95 According to the then environment minister, Jairam Ramesh, the tribunal was “one element” of a reformist approach to environmental governance. To quote the minister from the parliamentary debate:

Environment is becoming increasingly an interdisciplinary scientific issue … the fact of the matter is that we need judicial members because there are matters of law involved; and we need technical members who can provide scientific and technical inputs .... There are 5,600 cases before our judiciary today relating to environment. I am sure the number of cases will increase. We need specialised environmental courts. The Supreme Court has said this. The Law Commission has said this. India will be one of the few countries which will have such a specialised environmental court. I believe Australia and New Zealand are the two countries that have specialised Tribunals.Footnote 96

Thus, the MoEF acquired illustrative support and direction from Australian and New Zealand specialized environmental tribunals staffed by judges and expert commissioners, generally, being persons with expert knowledge in environmental matters. The government proposed the creation of a circuit system for the new tribunal. The government proposed four regional benches across the country. According to the minister, “a circuit approach would be followed to enable access for people. The court will go to the people. People would not come to the court. I assure you this.”Footnote 97

The Bill was passed by the Lok Sabha on 23 April 2010 and Rajya Sabha on 5 May 2010. The NGT Act 2010 received presidential assent on 2 June 2010.Footnote 98 The NGT Act implements India’s commitments made at the Stockholm Declaration of 1972 and the Rio Conference of 1992, to take appropriate steps for the protection and improvement of the human environment and provide effective access to judicial and administrative proceedings, including redress and remedies.

The NGT was established on 18 October 2010 and became operational on 5 May 2011 with New Delhi selected as the site for the principal bench.Footnote 99 The regional benches found their home in Bhopal for the central zone, Chennai for south India, Pune for the western territory, and Kolkata is responsible for the eastern region.Footnote 100 Additionally, to become more accessible, especially in remote areas, the NGT follows the circuit procedure of courts going to people and not people coming to the courts. Shimla has received circuit benches from Delhi,Footnote 101 as has Jodhpur from the central zone,Footnote 102 Meghalaya from the eastern zone,Footnote 103 and Kochi from the southern zone.Footnote 104

Further, as a learning new concept, the NGT was envisioned as a multifaceted and multi-skilled body in which the joint decision-makers held relevant qualifications and appropriate work experience either in law or in technical fields. Accordingly, the technical experts became “central,” rather than “marginal,” to the NGT’s normative structure. The combination of legal, scientific, and technical expertise had a dynamic impact on the content and development of environmental policies and law.

From 2011 onwards, both the external and internal “driving forces” displayed “new learning” in the NGT. The Supreme Court of India in 2012 re-engaged as an external driving force to institutionalize the NGT. The establishment of the NGT encouraged the Supreme Court to review its own environmental case-load and consider its limited environmental expertise. The Supreme Court in Bhopal Gas Peedith Mahila Udyog Sangathan v. Union of India Footnote 105 transferred all environmental cases, both active and prospective, to the NGT to render expeditious and specialized judgments and to avoid the likelihood of conflicts of orders between High Courts and the NGT. The court ordered:

in unambiguous terms, we direct that all the matters instituted after coming into force of the NGT Act and which are covered under the provisions of the NGT Act shall stand transferred and can be instituted only before the NGT. This will help in rendering expeditious and specialized justice in the field of environment to all concerned.Footnote 106

The Supreme Court of India again transferred more than 300 cases to the NGT in 2015. The Green Bench of the Supreme Court, headed by the then Chief Justice H. L. Dattu, decided to release several cases for swift decisions, thereby also shedding its pendency.Footnote 107

3.2.2 Learning New Meaning for Old Concepts

Internally, the NGT demarcated the operational changes by redefining the intellectual activity that embraced environmental disputes. Learning new meaning for old concepts was the second step reflecting “new learning” in the NGT. These internal forces within the tribunal corresponded to and helped the NGT to realize the vision of institutionalizing the larger welfare and interest of the society and environmental protection. They supported the attainment of the objectives of prevention and protection of environmental pollution, provide administration of environmental justice, and made them more accessible within the framework of the statute. There was a need to enhance the principles of environmental democracy and rule of law that include fairness, public participation, transparency, and accountability. In-house expertise with knowledge and skills came via a new visionary CEO (Chairperson Kumar in the case of the NGT). Change occurred through task and social leadership and customer-oriented demand (the litigants and lawyers) to access environmental justice.

In terms of learning new meaning for old concepts, “standing” was reformulated in terms of “an aggrieved person”Footnote 108 who has the right to approach the tribunal under its originalFootnote 109 or appellate jurisdictionFootnote 110 under the NGT Act. Traditionally in India, the concept of litigant “standing” in environmental matters has been broad and liberal, facilitated by public interest litigation (PIL) through two ways, namely representative and citizen standing. The Supreme Court acting as “amicus environment” locked together the issues of human rights and the environment to develop sui generis environmental discourse entertaining PIL petitions, seeking remedies, including guidelines and directions in the absence of legislation.Footnote 111

The NGT in a similar manner created receptive, accessible opportunities for the dispossessed and representative non-governmental organizations (NGOs), through the encompassing term “aggrieved person,” the genesis of which is derived from PIL. It championed parity of participation, thereby alleviating inequality and promoting recognition, capabilities, and functioning of individuals and communities in India’s environmental justice discourse. The NGT, in Samir Mehta v. Union of India,Footnote 112 explained the scope and ambit of the term. The tribunal stated:

An “aggrieved person” is to be given a liberal interpretation … it is an inclusive but not exhaustive definition and includes an individual, even a juridical person in any form. Environment is not a subject which is person oriented but is society centric. The impact of environment is normally felt by a larger section of the society. Whenever environment is diluted or eroded the results are not person specific. There could be cases where a person had not suffered personal injury or may not be even aggrieved personally because he may be staying at some distance from the place of occurrence or where the environmental disaster has occurred and/or the places of accident. To say that he could not bring an action, in the larger public interest and for the protection of the environment, ecology and for restitution or for remedial measures that should be taken, would be an argument without substance. At best, the person has to show that he is directly or indirectly concerned with adverse environmental impacts. The construction that will help in achieving the cause of the Act should be accepted and not the one which would result in deprivation of rights created under the statute.Footnote 113

The liberal approach of the tribunal based upon the benefits of PIL is evidenced in a series of cases.Footnote 114 Two reasons explain this approach. The first is the inability of persons due to poverty, ignorance, or illiteracy, living in the area or vicinity of the proposed project to understand the intrinsic scientific details coupled with the effects of the ultimate project and any disaster it may cause. Thus, it is the right of any citizen or NGO to approach the tribunal regardless of whether being directly affected by a developmental project or whether a resident of affected area or not. Second, the subservience of statutory provisions of NGT Act 2010 to the constitutional mandate of Article 51A(g) establishes a fundamental duty of every citizen to protect and improve the natural environment.

Recent workFootnote 115 provides evidence that identifies the parties to environmental disputes by analyzing some 1,130 cases decided by the NGT between July 2011 and September 2015. The most frequent plaintiffs were NGOs/social activists/public-spirited citizens. They account for 533 plaintiffs (47.2%) of 1,130 cases. For example, in Vimal Bhai v. Ministry of Environment and Forests,Footnote 116 the tribunal allowed an application by three environmentalists concerning the grant of an environmental clearance for the construction of a dam for hydroelectric power. The NGT ruled that the environmentalists constituted an aggrieved party and their claim for a public hearing concerning the granting of an environmental clearance was sustainable. Overall, the plaintiff group success rate stood at 38.3%. This significant number demonstrates both the opportunity of and the ability of public-spirited citizens and organizations to use the NGT as a route to seek remedies through collective proceedings instead of being driven into an expensive plurality of litigation.

Affected individuals/communities/residents brought 17.7% of all cases, with a success rate of 56%. For example, in R. J. Koli v. State of Maharashtra,Footnote 117 the tribunal allowed an application filed and argued in person by traditional fishermen seeking compensation for loss of livelihood due to infrastructural project activities. The positive encouragement by the NGT to litigants in person reflects a conscious effort on the part of the tribunal to promote access to environmental justice. Indigent and illiterate litigants have been encouraged to speak in their vernacular language (especially at regional benches) to ventilate their grievances and personal and community experiences. Confidence-building in the NGT has resulted in motivating litigation from within groups that traditionally had little or no access to justice. This reflects the NGT’s broad-based, people-oriented approach. The liberal interpretation of “aggrieved person” opened access to the tribunal to promote diffused and meta-individual rights. The NGT’s legitimacy is grounded in its inclusive participatory mechanisms.

Additionally, the NGT accepted “eco-centrism”—a nature-centred approach within its mandate of learning new meaning for old concepts. This is an emerging area wherein the tribunal recognizes and considers that conservation and protection of nature and inanimate objects are inextricable parts of life.Footnote 118 They have an impact on human wellbeing, as they form the life support system of planet Earth. The NGT, in its judgment in Tribunal on Its Own Motion v. Secretary of State,Footnote 119 recognized this approach by following the Supreme Court judgment in Centre for Environment Law, WWF- I v. Union of India Footnote 120 and stated “eco-centrism is, therefore, life-centred, nature-centred where nature includes both humans and non-humans. Article 21 of the Constitution of India protects not only the human rights but also casts an obligation on human beings to protect and preserve a species becoming extinct, conservation and protection of environment is an inseparable part of right to life.”Footnote 121

The learning new meaning for old concepts was further affirmed by the in-house judicial and technical experts through “trial and error learning based on scanning the environment” or, putting it simply, “inventing our own solutions until something works.”Footnote 122 The traditional adversarial judicial procedures associated with case management and disposal of the individual case have been altered because of the jurisdictional power and promotional activity of the NGT. Thus, centralizing scientific experts, as full court members, within the decision-making process promoted a collective, decision-making, symbiotic, interdisciplinary bench seeking to harmonize legal norms with scientific knowledge.

In its commitment to resolve environmental issues, the NGT members expanded and developed new procedures and powers that provided steadfast foundations to guide decision-making in environmental matters based upon a rights-based approach. Environmental dispute litigation in the NGT is not simply adversarial in nature. It is quasi-adversarial, quasi-investigative, and quasi-inquisitorial in nature to promote effective participatory parity and involvement of the person aggrieved—for instance, the adoption of an investigative procedure involving the inspection of affected sites by expert members.Footnote 123 The purpose of site inspections is to evaluate contradictory claims, positions, and reports filed by the respective parties.

The stakeholder consultative adjudicatory process is the most recent of the NGT’s problem-solving procedures. Major issues having a public impact either on public health, environment, or ecology can be better handled and resolved when stakeholders are brought together alongside the tribunal’s scientific judges to elicit the views of those concerned—government, scientists, NGOs, the public, and the NGT. Stakeholder process evokes a greater element of consent rather than subsequent opposition to a judgment. The ongoing Ganga river,Footnote 124 Yamuna river,Footnote 125 and air pollutionFootnote 126 cases are illustrations of the new stakeholder consultative adjudicatory process involving open dialogue with interested parties. In K. K. Singh v. National Ganga River Basin,Footnote 127 the NGT observed:

the Tribunal adopted the mechanism of “Stakeholder Consultative Process in Adjudication” to achieve a fast and implementable resolution to this serious and challenging environmental issue facing the country. Secretaries from Government of India, Chief Secretaries of the respective States, concerned Member Secretaries of Pollution Control Boards, Uttarakhand Jal Nigam, Uttar Pradesh Jal Nigam, Urban Development Secretaries from the States, representatives from various Associations of Industries (Big or Small) and even the persons having least stakes were required to participate in the consultative meetings. Various mechanism and remedial steps for preventing and controlling pollution of river Ganga were discussed at length. The purpose of these meetings was primarily to know the intent of the executives and political will of the representative States who were required to take steps in that direction.Footnote 128

In this way, efforts are being made to ensure scientifically driven judgments reflect the interests, expectations, and plans of stakeholders to produce decisions that support sustainable development and recognize the wider public interest.

The exercise of suo motu power (on its own motion) proceedings in environmental cases is another situation indicating learning new meaning for old concepts. In suo motu proceedings, a superior court initiates proceedings as PIL in the public interest and acts on its own volition in the absence of parties.Footnote 129 The NGT’s jurisdiction is typically triggered by an aggrieved person filing a motion. Interestingly, the NGT Act 2010 does not expressly provide the authority to initiate suo motu proceedings. Cases such as increased vehicular traffic in Himachal Pradesh,Footnote 130 dolomite mining in the tiger reserve forest in Kanha National Park,Footnote 131 groundwater contamination in the water supply lines and bore wells in Delhi,Footnote 132 and the clearing and felling of trees in the Sathyamanglam Tiger ReserveFootnote 133 are illustrative of the NGT initiating controversial suo motu proceedings. These cases reflect the tribunal’s self-proclaimed, expansionist power to review environmental issues, ab initio, simply on the grounds of environmental protection and human welfare. For the tribunal, “suo motu jurisdiction has to be an integral part of the NGT for better and effective functioning of the institution. There are some inherent powers which are vital for effective functioning and suo motu jurisdiction is one such power.”Footnote 134

The NGT also conferred upon itself the power of judicial review—yet another important and controversial instance of learning new meaning for old concepts. The Constitution of India vests the Supreme Court under Article 32 and High Courts under Article 226 with the power of judicial review to ascertain the legality of legislation or an executive action.Footnote 135 However, the power of a tribunal as a “quasi-judicial body” to undertake the judicial review has often been disputed.Footnote 136 In L. Chandra Kumar v. Union of India,Footnote 137 the Supreme Court observed:

the Tribunals are not substitutes for the High Courts, and they can carry out only a supplemental, as opposed to substitutional role, since the power of the High Courts and Supreme Court to test the constitutional validity of legislations can never be ousted or excluded. The Tribunals are therefore not vested with the power of judicial review to the exclusion of the High Courts and the Supreme Court.Footnote 138

However, in a series of cases,Footnote 139 the NGT declared the tribunal is competent and is vested with the jurisdiction and power of judicial review. The tribunal has all the characteristics of a court and exercises the twin powers of judicial as well as merit review. There is no provision in the NGT Act 2010 that curtails its jurisdiction to examine the legality, validity, and correctness of delegated legislation regarding the Acts stated in Schedule I to the NGT Act 2010.Footnote 140 The exercise of judicial review has evoked mixed responses. Environmentalists felt a strong message is delivered that the NGT is concerned with not only the merits of the decision, but also the decision-making process. As an independent body, the NGT aims to protect individuals against abuse or misuse of power by the authorities.Footnote 141 However, the MoEF on the other hand felt that it amounted to usurping its jurisdiction. It claimed that the NGT can only examine decisions and cannot strike down a statute.Footnote 142

The NGT’s willingness regarding “inventing our own solutions until something works” to resolve the environmental issues reflects its expansive self-created procedure for learning new meaning for old concepts. Consequently, it produced changes in both the institutional and the external landscapes by antagonizing certain state High Courts and furthering the distance from the MoEF.

3.2.3 Adopting New Standards of Evaluation

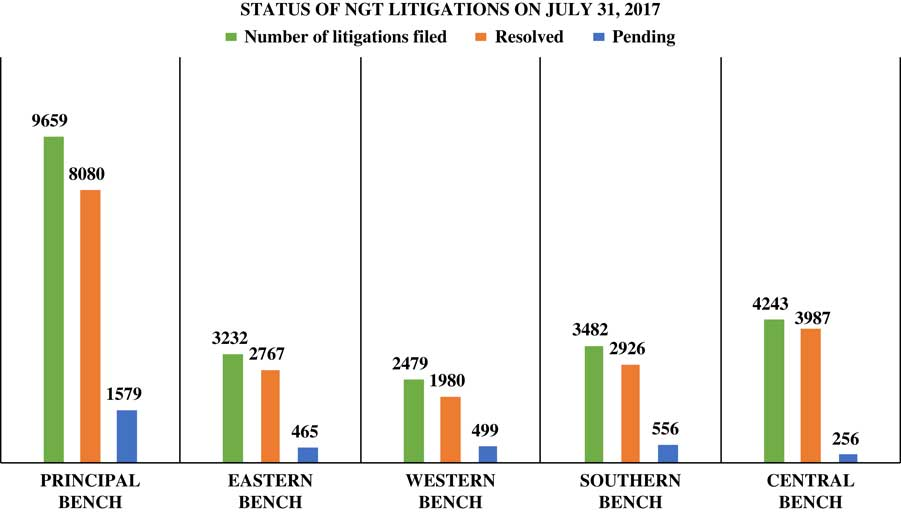

Along with the new concepts comes adopting new standards of evaluation for a transformation change encouraged by drastically increased environmental problems including a rise in pollution levels and demographic pressures. “Cost and time” help in evaluating the standards in an organization for customer expectation.Footnote 143 Contextualizing within the NGT, adopting new standards of evaluation envisages “aggrieved person” expectation for a faster, cheaper, and more effective way to access to environmental justice, thereby promoting participatory parity. The internal driving force of the NGT, through its leadership and regulatory requirements, helps in evaluating the measurable standards. It allows aggrieved persons to initiate proceedings before the NGT and “assert diffused and meta-individual rights.”Footnote 144 The NGT rules provide for an application or appeal where no compensation has been claimed to be accompanied by a fee of INR 1,000 (GBP 10).Footnote 145 Where compensation is claimed, the fee is equivalent to 1% of that compensation, subject to a minimum of INR 1,000 (GBP 10).Footnote 146 Thus, the low fees reflect the NGT’s open-door commitment to the poor. Another feature of the NGT is its ability to fast-track and decide cases within six months of application or appeal.Footnote 147 To illustrate, Figure 5 demonstrates the status of NGT litigation as of 31 July 2017.

Figure 5 Status of litigation in the five NGT benches. Source: NGT Annual Report 2017

The official figures show 23,095 cases were filed, of which 19,740 were decided and 3,355 were pending before the NGT. This demonstrates that 85.4% of the cases were decided whereas 14.6% of cases remained pending. The NGT’s legitimacy is grounded in its inclusive participatory mechanisms (standing, time, and costs) that promote dynamism and capability, thereby providing victims of environmental degradation with access to the tribunal.

Thus, the institutionalization and transformation sought by the NGT are a metamorphosis of societal environmental interests that encapsulate the wellbeing of not only the individual, but also the larger public interest. The relative position of the inter-dependent “driving forces” (MoEF until 2011, Supreme Court of India, and the NGT’s internal forces) came together and expressed themselves for “new learning” by the establishment of an organized institution: the NGT through internal procedural expansion and change.

3.2.4 New Learning, Change, and the Restraining Forces in Action

However, this stage of “new learning” has not occurred without struggle. There existed “restraining forces.” The MoEF after 2011 and the High Courts gained momentum and strength to restrict the proactive NGT as it sought to take control of the intellectual space for the right to regulate or respond to environmental issues.

From its inception, and particularly after 2011, the NGT faced institutional challenges due to limited co-operation and hesitant operational commitment of MoEF and state governments. Initially, the understaffed bench and inadequate logistic and infrastructure facilities, coupled with inappropriate housing for bench appointees, led to the resignation of three judicial members: Justices C. v. Ramulu, Amit Talukdar, and A. S. Naidu.Footnote 148 The state’s inaction required intervention by the Supreme Court to remedy the situation.Footnote 149 Senior counsel, Gopal Subramaniam, appeared on behalf of the NGT and informed the Supreme Court about “a very sorry state of affairs” affecting the tribunal. He said:

the members have been put up in the middle of quarters of Class III and IV employees. The initial budget of INR 32 crores [GBP 3,505,462] was slashed to INR 10 crores [GBP 1,095,513] to be further reduced to INR 6 crores [GBP 657,308]. Each of the members is paying from his own pocket for travel. They don’t even have a supply of food at work and they are compelled to get food from the canteen. Is this how the government proposes to treat the sitting and former judges of the High Courts and Supreme Court of India?Footnote 150

The Supreme Court described the treatment experienced by the members of the NGT as “utterly disgusting.”Footnote 151 Accordingly, the Supreme Court stated that the NGT benches must become fully functional by 30 April 2013.

The Bhopal bench started functioning in the basement of a building, despite affidavits being led by the state government claiming suitable accommodation had been provided to the NGT. Justice Singhvi reacted sharply by observing “we cannot appreciate that a misleading statement was made before the highest court. A false affidavit was led before the apex court. Accommodation does not mean basement.”Footnote 152 The Pune bench was treated in a similar derisory manner. It was inaugurated on 17 February 2012, but the lack of state support resulted in delays into March 2013. Kolkata fared even worse. The state of West Bengal failed to respond to the orders of the Supreme Court. The NGT chairperson inspected the Kolkata bench and found the premises, particularly the accommodation offered to judges, to be “shabby, uninhabitable and without a toilet.”Footnote 153

There is an explanation for this degrading treatment that affected the establishment and the early operational effectiveness of the NGT benches. There existed an unresponsive and dysfunctional state administration that failed to appreciate the importance of green issues. The then MoEF Minister Jairam Ramesh was known for raising the green profile and hailed by many as an outstanding environment minister. Nevertheless, he was fighting battles within his own ministry, the MoEF. Personally, “he remained accessible and responsive but he could not ensure that his ministry officials were also accessible and responsive.”Footnote 154 Ramesh described the ministry’s environmental working position as:

It’s a huge bureaucracy. There is a structural problem …. It’s easier to reform laws and procedures and hope that would create a new mind-set in these people rather than try for a structural change …. This is not a ministry where at the end of the day I can say that I put 10,000 mw of generating capacity, I have started 300 trains, or I opened 60 new mines. It’s basically a regulatory institution. To that extent unidirectional goals are very difficult to achieve.Footnote 155

Former minister Ramesh supported and guided the enacting NGT Bill through Parliament but was unable to establish and promote the benches due to his removal from the MoEF in 2011.Footnote 156 From 2011 onwards, the “restraining forces” within the MoEF reflected structural inertia, resistance to change, and indifference to an extent that they were reluctant to provide appropriate financial and structural support.

Additionally, the “new learning” stage witnessed the MoEF and High Courts acting as “restraining forces” questioning the alleged self-validation by the tribunal of further jurisdictional powers. The colonization of intellectual space partly by the public promotion of its jurisdiction and through its effectiveness in protecting both the environment and the interests of affected parties was not well received by the MoEF and some High Courts.

The exercise of suo moto powers by the NGT was raised and challenged by the MoEF. The ministry had refused to confer this power on the tribunal despite repeated requests to do so. In an affidavit before the Supreme Court of India in 2013, the MoEF stated:

the government of India has not agreed to confer suo motu powers on the Tribunal. It is for the NGT, an adjudicatory body, to follow the provisions of the NGT Act 2010 … resulting in embarrassment to the government before Parliament.Footnote 157

The claim of alleged judicial overreach was bolstered when the High Court of Madras restrained the NGT Chennai bench from initiating suo motu proceedings. The High Court stated:

NGT is not a substitute for the High Courts. The Tribunal has to function within the parameters laid down by the NGT Act 2010. It should act within four corners of the statute. There is no indication in the NGT Act or the rules made thereunder with regard to the power of the NGT to initiate suo motu proceedings against anyone, including statutory authorities.Footnote 158

Further, an order passed by Madras High Court dated 7 July 2015 stated that the NGT should not initiate more suo motu proceedings.Footnote 159 Jurisdictional expansion in this regard remains unsettled, although its procedural value is significant. It allows the NGT to initiate proceedings and permits the tribunal to roam far and wide, searching for pressing environmental issues that it considers to be in the public interest.

The NGT’s self-defined expansion of powers to include judicial review reflects further territorial extension at the potential cost of alienation and challenge by the High Courts that previously and exclusively enjoyed the exercise of these powers. For example, the Bombay High Court in Central Indian Ayush Drugs Manufacturers Association v. State of Maharashtra Footnote 160 decided that the NGT does not possess power to adjudicate upon the vires or validity of any enactment in Schedule I or of subordinate legislation framed under such enactment. Increasing tribunalization is viewed by some High Courts as serious jurisdictional encroachment, thereby causing institutional confusion, collusion, and complexity.Footnote 161

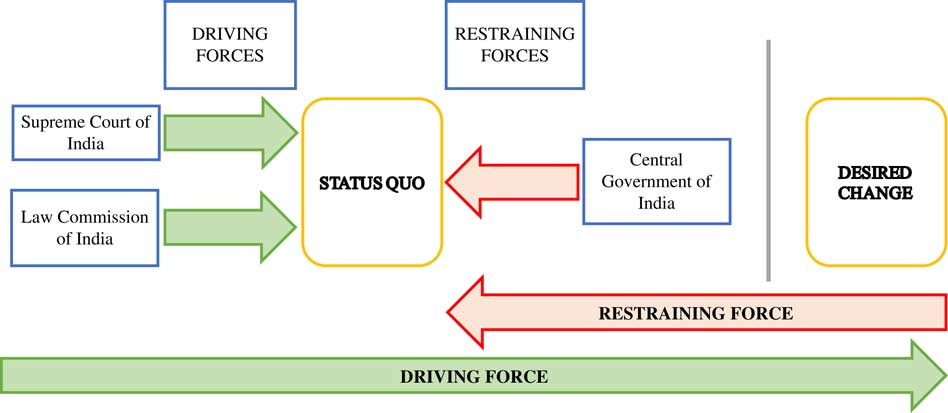

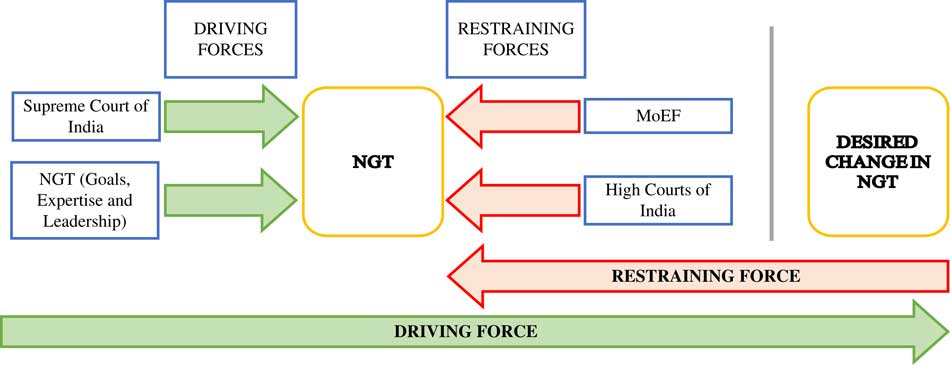

Figure 6 reflects the interplay of the principal “driving forces” and “restraining forces.” The “driving forces” aimed to bring a change whereas the “restraining forces” represent resistance to the change.

Figure 6 Interplay between driving and restraining forces. Source: Author

However, as the NGT overcame suspicion bordering on hostility with the support of the Supreme Court and its own results-based commitment, it ensured that the terms of the NGT Act 2010 were given practical effect throughout India. Despite initial setbacks and continuing concerns from powerful agencies, the “driving forces” outweighed the “restraining forces,” allowing the move to the next stage: refreeze.

3.3 Refreeze

Lewin and Schein’s framework recognizes that refreezing is the final step in any change wherein “the new learning will not stabilize until it is reinforced by actual results.”Footnote 162 Refreezing represents institutionalization of change wherein the “new learning” and behaviour become habitual, as it will “produce better results and be confirmed.”Footnote 163 However, the refreeze stage may not be permanent and could lead to the restart of the “three-step model”; if it

does not produce better results, this information will be perceived as a disconfirming information … systems are, therefore, in perpetual flux, and the more dynamic the environment becomes, the more that may require an almost perpetual change and learning process.Footnote 164

The refreeze stage for the NGT is both complex and contentious.

The institutionalization of the NGT and its reinforcement by actual results indicate that it had moved into the refreeze status. The manifestation of the actual results or outcome is witnessed at both the international and the national levels. Internationally, the NGT is considered as a framework for “the world’s largest network of local environmental Tribunals, expected to increase citizen access to environmental justice.”Footnote 165 Recently, the World Commission on Environmental Law and the Global Judicial Institute on the Environment expressed their great appreciation for the NGT, for its precedent-setting jurisprudence, as well as its international conferences over the several years that successfully brought together parliamentarians, judges, lawyers, scientists, academics, students, and other international and national delegates.Footnote 166

At the national level, the practical testimony to “producing better results” is evidenced by the significant case growth in the NGT. Figure 7 illustrates this growth.

Figure 7 Status of litigation in five NGT benches. Source: NGT website (http://www.greenTribunal.gov.in/)

The NGT has found favour with the common man: “aggrieved person” seeking to access environmental justice. Figure 7 represents the status of NGT litigation from July 2011 to January 2018. The growing public awareness and the confidence in the NGT symbolize widespread credibility that promotes and supports environmental justice.

The performance indicator for actual and better results is further substantiated by the NGT producing judicially binding decisions that offer ecological, technological, and scientific resource knowledge. By reconfiguring its jurisdictional boundaries, its decisions through expansive rationale and innovative judgments go beyond the “courtroom door” with far-reaching social and economic impact. The legal lens has been expanded by the NGT decisions through either formulating policies or assisting state governments with the implementation of these policies, thereby adopting both a problem-solving and a policy-creation approach.

A major innovation is the NGT’s willingness to offer scientifically based structural planning and policies that respond creatively to weak, ineffective regulation or even the absence of regulation. The scientific experts apply constructive interpretation to expand the scope of rules and regulations if the activity is injurious to public health and environment. Such an interpretation serves the public interest in contrast to the private or individual interest. For example, in Asim Sarode v. Maharashtra Pollution Control Board,Footnote 167 the NGT identified the absence of notified standards for used-tyre disposal. Open tyre burning is toxic and mutagenic. Stock-piled used tyres can also be a health hazard, as they become breeding grounds for diseases and can catch fire. Accordingly, the NGT directed the regulatory agencies to urgently develop regulations dealing systematically with the issue based on the “life-cycle approach,” considering the pollution potential, data on tyre generation, technology options, techno-economic viability, and the social implications based on the principles of sustainable development and the precautionary principle. Again, in Haat Supreme Wastech Limited v. State of Haryana,Footnote 168 the NGT expanded the scope of rules relating to bio-medical waste-treatment plants. The Bio-Medical Waste (Management and Handling) Rules 1998 are silent about whether the establishment and operation of a treatment plant require environmental clearance. Bio-medical waste, by its very nature, is hazardous. The tribunal directed that it is mandatory to obtain environmental clearance for the treatment plants. This requirement, when properly carried out, would help to ensure an appropriate analysis of the suitability of the location and its surroundings, the impact on public health, and a more stringent observation of parameters and standards by the project proponent.Footnote 169

In addition, the NGT adopted an accountability-focused approach whereby a diverse set of actors including governmental and local authorities, companies, and multinational corporations were restrained in compromising human welfare and the ecology. Importantly, in its decisions, the NGT identified the MoEF and related regulatory agencies as demonstrating indifference, ultra vires, or negligence in the exercise of their responsibilities.Footnote 170 In Jai Singh v. Union of India,Footnote 171 the NGT identified failure of government and regulatory authorities in preventing and controlling pollution arising from illegal and unauthorized mining, transportation, and running of screening plants and stone crushers. The tribunal stated:

the activity must be brought within the control of legal and regulatory regime. The concerned authorities of the Government and Boards should not only realise their responsibility and statutory obligation but should ensure that there is no unregulated exploitation of the natural resources and degradation to the environment. Respondents, including the State Government, the Boards, MoEF and other concerned authorities have permitted such activity despite orders of the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India, the High Courts and the Tribunal. There is definite evidence on record to show that illegal mining has continued .... Merely denying the authenticity of the photos, videos and other documentary evidences on the pretext that they were doctored would not amount to discharge of the onus placed upon the respondents.Footnote 172

Frequently, the MoEF has been subjected to severe criticism by the NGT for failing to observe its own procedural rules, such as the improper granting of licences without prior environment impact assessments (EIAs) being completed or appropriately conducted.Footnote 173 In India, there have been serious failures regarding cumulative environment impact assessment studies, rendering this crucial process meaningless. For example, in Krishi Vigyan Arogya Sanstha v. MoEF,Footnote 174 the tribunal cancelled the grant of environmental clearance for a coal-based thermal-power project in the absence of a proper cumulative environmental impact assessment (CEIA). No scientific assessments were done in relation to expected excess cardiovascular and respiratory mortality, children’s asthma, and respiratory dysfunction attributable to the exposure to the air pollutants from the plant, the impact on the water bodies and its impact on aquatic life, and the effect of nuclear radiation in and around the plant. In Prafulla Samantray v. Union of India Footnote 175 (the POSCO case), the issue before the NGT was opposition to the proposed POSCO project, involving the construction of an integrated steel plant with a service seaport at Paradip in the state of Orissa. The construction of the proposed plant and port threatened the area’s unique biodiversity and anticipated the dislocation and displacement of the long-standing forest-dwelling communities. The NGT held no meticulous scientific study was undertaken, leaving lingering and threatening environmental and ecological doubts unanswered. Factors such as the siting of the project, present pollution levels, the impact on surrounding wetlands and mangroves and their biodiversity, risk assessment with respect to the proposed port project, the impact of source-of-water requirements under competing scenarios, and the evaluation of the zero-discharge proposal were not studied. The tribunal required a comprehensive and integrated EIA based on at least one full year of baseline data, especially considering the magnitude of the project and its likely impact on various environmental attributes in the ecologically sensitive area. The initial clearance was set aside as arbitrary and illegal and vitiated in the eyes of law.

The tribunal has been prepared to call senior civil servants to the court having heard often inappropriate or implausible explanations from the MoEF and related regulatory authorities’ decisions including union and state governments. For example, the NGT stated:

Directions issued by us have not been complied. Though the counsel for MoEF submits that report has been filed which we notice, least we could say about that it is misleading and is not in terms of our direction. The affidavit as directed has not been filed. We direct presence of deponent in the affidavit, namely, Dr Sunamani Kereketta, Director, MoEF before the Tribunal on the next date of hearing.Footnote 176

On occasions, senior civil servants have been told that they face a term of “state hospitality” (jail) for statements bordering on contempt.Footnote 177 Indeed, in Sudeip Shrivastava v. State of Chhattisgarh,Footnote 178 the tribunal took the bold, provocative step of criticizing the Minister of State for Environment and Forest and the MoEF for acting arbitrarily and ignoring relevant material issues that would have contributed to a holistic appraisal of the environmental problem.

The tribunal has on occasions reprimanded the regulatory authorities in the strongest language in open court. Such public criticism has done nothing to endear the tribunal to key agencies and ministerial officials unused to such embarrassing rebuke that exposes their inefficiency or indifference. For instance, in the Ganga pollution case,Footnote 179 the NGT stated “it is really unfortunate that the Ganges continues to be polluted. Why don’t you [the state and federal governments] do something? You raise slogans [about cleaning the river] but do exactly opposite of that.”Footnote 180

In the Delhi air-pollution case,Footnote 181 the NGT commented:

every newspaper has been carrying headline that the air pollution [in Delhi] was going to be higher this week. Still you took no action .... Are people of Delhi supposed to bear this? In this country, it is a dream to have prescribed norms of air quality.

In the Goa Foundation v. Union of India case,Footnote 182 the NGT critically observed:

The MoEF is the “most messy” Ministry, for its changing stance regarding protection of the Western Ghats …. Why can’t it (MoEF) take a clear stand on whether it wants to keep the Gadgil report or not? If it can’t then we will have to call the MoEF secretary in person to clear the matter …. Despite our specific directions, MoEF has failed to file an appropriate affidavit. A vague affidavit has been presented before the Tribunal today.Footnote 183

Gill’s study documents that regulatory agencies (comprising the MoEF, state government, local authorities, and pollution-control boards) constituted 942 defendants (83.4%) of 1,130 reported judgments between 2011 and 2015.Footnote 184 The MoEF was the defendant in 284 cases (25.1%); state government appeared as the defendant in 341 cases (30.2%); a local authority was listed in 78 cases (6.9%); and pollution-control boards in 239 cases (21.2%). The data suggest a repeated failure on the part of regulatory authorities to undertake their statutory environmental protection duties and social responsibilities regarding environmental matters. The regulatory agencies dealing with environmental matters have been unable to deliver, according to an official enquiry, due to:

a knee-jerk attitude in governance, flabby decision-making processes, ad hoc and piecemeal environmental governance practices …. The institutional failures include lack of enforcement, flawed regulatory regime, poor management of resources, inadequate use of technology; absence of a credible, effective enforcement machinery; governance constraints in management; policy gaps; disincentives to environmental conservation, and so on.Footnote 185

The failure of central and state agencies to follow due process has been a regular and major cause of complaint from aggrieved persons who seek redress from the NGT. The tribunal has proved stubbornly determined and successful in enforcing the environmental regulations. Its case-law demonstrated its ability and willingness to require transparency and accountability that ultimately constitute the building blocks of good governance and environmental democracy.

3.3.1 Thawing and Restart Process

However, the institutionalization of the NGT in the refreeze stage has importantly triggered a subsequent thawing or renewal process. The external “restraining forces” slowly and steadily have become sufficiently powerful to destabilize the NGT and set in motion a fresh change. These volatile forces are gaining momentum by creating situations whereby field-level changes become inevitable, and hence the restart of the process. Again, the “restraining forces” include political and economic interests, policy and legislative interventions, and regulatory agencies, particularly the MoEF.

Economic interests and the national growth agenda are powerful “restraining forces” impacting upon the NGT. The current national economic strategy has assumed heightened significance under the leadership of India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi. He is known for his ability to drive change and his commitment to accelerate sustainable growth in India. Prime Minister Modi, at the February 2018 World Sustainable Development Summit, emphasized the current environmental problems being faced by the developing nations and the need for a development process that is inclusive and sustainable, resulting in benefit to all stakeholders:Footnote 186

This summit is a reinforcement of India’s commitment to a sustainable planet, for ourselves and for future generations. As a nation, we are proud of our long history and tradition of harmonious co-existence between man and nature. Respect for nature is an integral part of our value system. Our traditional practices contribute to a sustainable lifestyle. Our goal is to be able to live up to our ancient texts which say, “Keep pure For the Earth is our Mother and we are her children.” India has always believed in making the benefits of good governance reach everyone. Our mission of “Sabka Saath Sabka Vikas” is an extension of this philosophy. Through this philosophy, we are ensuring that some of our most deprived areas experience social and economic progress on par with others.Footnote 187

Nevertheless, Modi is also known as a pro-business, market-oriented reformer who aims to double the Indian economy in the next seven years. Modi claims “India would have a $5 trillion economy by 2025.”Footnote 188 Modi’s efforts in building India’s global appeal for investors by introducing an “ease of doing business” strategy has yielded returns. India rose 30 places to 100 in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business global rankings and was named as one of the top ten countries in reforming its business environment.Footnote 189

Notwithstanding these ambitious commitments, the reality within India remains disturbing. There continues to exist a failure gap between the public statements of Prime Minister Modi and their application in practice by his “agents,” being the relevant ministries, regulatory agencies, and civil servants. An illustration of unfettered economic promotion occurred in May 2016, when the then Minister of Environment and Forests, Prakash Javadekar, stated his ministry granted environmental clearance (EC) to 2,000 projects in 190 days for ease of doing business. The minister stated environment clearances are given without compromising stringent pollution norms.Footnote 190 However, evidence suggests that regulatory environmental laws and procedures were ignored or short-circuited in the race for economic returns. Errors include failure to provide mandatory documentation, inadequate stakeholder participation, and deliberate concealment or submission of false or misleading information for the EC process. A study by the Centre for Science and Environment, a Delhi-based research and advocacy organization, stated that, between June 2014 and April 2015, 103 mining projects and 54 infrastructure projects were granted ECs. The coal-mining sector was a special beneficiary, as projects were allowed in critically polluted areas via a diluted public-hearing requirement.Footnote 191 The data showed that projects were being cleared and processes were made so convoluted that they stopped working to protect the environment. The report stated:

overall trend suggests that green clearances have been made faster through incremental changes “easing” the clearance process. However, there is no evidence that the quality of EIA reports has improved or enforcement on the ground have become more effective.Footnote 192