1. INTRODUCTION

In recent years, the Xi Jinping administration has come “out of the shadows”Footnote 1 to openly proclaim dominance of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) over all aspects of law-based governance. Accordingly, the 2014 Fourth Plenum of the 18th Party Congress declared that the “Party’s leadership must be implemented across the complete process of governing the country in accordance with the law.”Footnote 2 Moral virtue, however, has also come to be strongly profiled in matters of Party concern. How, then, does morality fit with the Xi administration’s aspirations to dominate legal processes in this way?

Issued on 25 December 2016, the CCP Central Committee’s Guiding Opinions on Further Integrating Socialist Core Values into the Construction of Rule of Law (“Guiding Opinions”) specify that all laws, regulations, and public policies should be deployed so as to guide the correct value orientations of people in society.Footnote 3 On 7 May 2018, the CCP Central Committee announced a plan to “fully incorporate Socialist Core Values into all legislation” in the next five to ten years, claiming the integration of “governing the nation in accordance with the law” (yifa zhiguo) and “rule by morality” (yide zhiguo) to be the most distinct feature of the socialist rule of law with Chinese characteristics.Footnote 4 Here, the configuration of socialist rule of law by PRC president and CCP general secretary, Xi Jinping, exhorts the conduct of virtuous leadership as an integral part of the process of governing through the law. The relationship between law and morality has, of course, been at the core of Chinese political philosophies from ancient times through to the modern and contemporary eras, notably the Jiang Zemin period. The Guiding Opinions and the subsequent action plan, however, take this law–morality amalgam to new ideological heights.

Since its inception, the CCP has never shied away from using moral campaigns. The current ideological push, however, is the first time that the Party has required a set of prescribed values, known as the Socialist Core Values, to be integrated into all legal and judicial processes. There are 12 designated Socialist Core Values, each promoted as a concept without detailed theoretical explanation, which the Xi leadership presents as officially sanctioned moral virtues. These are national values of prosperity, democracy, civility, and harmony; the social values of freedom, equality, justice, and rule of law; and the individual values of patriotism, dedication, integrity, and friendship. The CCP now requires these values to be “integrated” (xiang jiehe) into the socialist rule of law (shehui zhuyi fazhi) through the routine decision-making work of the courts.Footnote 5 This is part of a broader propaganda programme to instil Xi era socialist values across all areas of governance. The stated motivation of this moral push is to enable a “unification of thought” between the Party on the one hand and the people that the Party governs on the other.Footnote 6 We argue that such justification is a rhetorical attempt to present the Party as a kind of Communist Hobbesian “commonwealth”—that is, as a unity of a governing body, here the Party, and its subjects. Presenting the ruler and the ruled as a unitary construct “enables cooperation where there would otherwise be competition.”Footnote 7 Unifying the Party and its subjects in this way, of course, requires unifying thought (tongyi sixiang). Morality—good moral judgement—is the highest form of thought and is instrumental to the maintenance of order in society. According to this logic, once unification of thought between the ruler (the Party) and the ruled is achieved, the Party will be able to govern effectively through the law and its institutions. In this sense, the Socialist Core Values propaganda project can be envisaged as an offshoot of the much broader social stability agenda that has been central to the Party’s social control machinery for decades—an agenda that requires the full support of the politico-legal (zhengfa) system.

At heart, the Party’s push to integrate moral values and law is about maintaining order in society. Foregrounding notions of maintaining order, this article examines the ideology behind the promotion and modelling of Socialist Core Values in the legal realm from two interrelated perspectives. The first concerns the relationship between law and morality, while the second is the supremacy of Party rule. We begin by arguing that the Party’s calls for a law–morality amalgam through all processes of governing the nation in accordance with the law can be understood as a form of “pan-moralism.”Footnote 8 We then examine the mounting of a moral justification—represented by the Socialist Core Values—for the absolute supremacy of CCP rule over all aspects of law-based governance. As we explain in Section 5 of this paper, this argument is based on, while also extending, the idea of the “Leviathan” proposed by Thomas Hobbes. Through a two-pronged argument that focuses first on the Party’s calls for a law–morality amalgam and second on the moral justification of Party supremacy, we assert that the Xi Jinping administration is creating a virtuous Leviathan. Below, we begin with a short outline of each of the two elements of our argument and then move on to treat each discretely.

2. THE TWO-PRONGED ARGUMENT

The first prong of the argument draws attention to the Party’s desire to amalgamate law and morality. The Socialist Core Values espoused in unison with calls to observe Chinese tradition are an integral part of the official ideology of Xi’s New Era Socialism with Chinese characteristics. This new era ideology claims to offer unique Chinese wisdom and a Chinese approach to solving the problems that face humankind.Footnote 9 In January 2017, the CCP Central Committee and State Council issued the “Opinions on Implementing the Engineering Project of Preserving and Developing Excellent Chinese Traditional Culture.” The purpose of these “Opinions” was to boost “cultural confidence” and, in particular, “to build a strong socialist cultural country, to enhance the country’s cultural soft power and to achieve the Chinese Dream, the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”Footnote 10 The “Opinions” state that the engineering project of preserving and developing excellent Chinese traditional culture must be guided by the Socialist Core Values.Footnote 11

In July 2017, Chinese legal scholar, Xu Xianming, published an article in a Party-based human rights online journal explaining the unique relationship between law and morality, and the relationship of these both to China’s past and to its future rejuvenation. Among other conceptual highlights, Xu offered the following three observations about the relationship between law and moral virtue on the one hand and the Party leadership on the other:

1) In ancient China, there was the fine tradition of “Officials as Teachers.” Under the new historical conditions, leading cadres should both possess the thinking and capacity for the rule of law. “Speeches that do not conform to law, should not be followed. Actions that do not conform to the law, should not be esteemed. Things that do not conform to the law, should not be done.” Leading cadres should possess the demeanour of gentlemen “to cultivate by virtue, to establish credibility by virtue, to convince the public by virtue” …

2) The advantage of Chinese culture is it caters to the ultimate spiritual needs and behavioural choices of humans without resorting to religion. Why is Chinese civilisation able to withstand all kinds of shocks and still survive? Among many reasons, the most important one is China’s political and cultural DNA that combines the rule of law and rule of morality. Since the Qin Dynasty unified China, the rulers of all dynasties have used the law to safeguard the central authorities, and without exception maintained national unity by rule of law and rule of morality.

3) On December 9, 2016, the CPC Central Committee Political Bureau held its 37th collective study, with the theme “The Rule of Law and Rule of Morality in Chinese History.” General Secretary Xi Jinping presided over the study and delivered an important speech. The speech profoundly revealed the relationship between the rule of law and the rule of morality, enriched and developed Marxist theories about the relationship between law and morality, and expounded on how to uphold the rule of law with the rule of morality under the new historical conditions. This showed the direction for the socialist rule of law with Chinese characteristics.Footnote 12

In creating a link between contemporary times and the distant past, Xu’s words reflect the current administration’s intention to undertake a recalibration of Jiang Zemin era “rule by morality” propaganda to promote a strategic policy emphasis on practices that have, as we shall explain below, been a feature of governance in China since the time of the Qin dynasty.

We argue that this assertion of the role of morality in governing China can be understood as a form of “pan-moralism,” discussed as follows by moral philosopher, Vlastimil HálaFootnote 13 :

“Pan-moralism” I define as a certain “overwhelming” or exaggeration of the claim of the moral standpoint. The representatives of such a conception extend the primacy of the morally motivated and justified viewpoint (or their own particular conception of morality) even into areas which ought to be governed by particular standard rules deriving from the given legal system.Footnote 14

Here, Hála refers specifically to the case of the Czech Republic, and in particular to the characteristics of an authoritarian or totalitarian regime within that Republic. To Hála, pan-moralism refers to the persistent and problematic morally motivated attitude held by members of society in the transitional period between a totalitarian and democratic social systems. Chinese “new era” pan-moralism, on the other hand, is a top-down process that resonates with Confucian concepts and which has recently emerged to support the ushering in of a new era of virtue-governed politics. As we shall argue, pan-moralism in the Chinese political context is the result of merging political and ideological power in a manner characteristic of the Confucian–Legalist political system—a system that sociologist Dingxin Zhao has examined through empirical and historical evidence.Footnote 15 In this sense, the dual emphasis of the Xi Jinping administration on “rule of law” and “rule by morality” demonstrates an explicit return to the resilient imperial Confucian–Legalist paradigm. Rooted in Confucian and Socialist Utopias, pan-moralism as it operates in China is based on the implicit assumption that it is possible to “restitute,” through political means, the originally authentic and just relations between people.Footnote 16 From the perspective of legal theory, this pan-moralist stance effectively silences constructive critique, proposed by neo-Confucians such as Mou Zongsan and contemporary law scholars such as Liu Zuoxiang, Sun Li, and Ji Weidong, on the limits of moral authority and the independence of the law.

The second aspect of the article’s two-pronged argument centres on the moral justification—represented by the Socialist Core Values—of the supremacy of CCP rule. As Xi Jinping asserted in his Party general secretary report to the 19th Congress in October 2017, the Party must exercise overall leadership encompassing all areas of endeavour in every part of the country.Footnote 17 The total alignment of legal and judicial processes with the Socialist Core Values not only justifies the necessity for an all-virtuous Party that is capable of bringing peace, unity, justice, and prosperity for every member of society, but, post 2012, also legitimates the idea of the Party as an organ that is increasingly characterized by the unmitigated concentration of power. In referring to the highly centralized power Xi proclaims for the Party and for himself, we borrow the word “Leviathan” from the iconic work by Thomas Hobbes.Footnote 18 Originally a giant sea monster referred to in sacred Hebrew texts, the “Leviathan” was used by Hobbes as a metaphor for the omnipotent, all-powerful ruler to whom the people, as part of a social contract that ensured their protection, submitted their individual rights. Drawing on some insights presented by John Kane and Kerry Brown,Footnote 19 we suggest that the quasi-religious presentation of the Party as the country’s Common Power, and the general secretary as the central core of that power, can be explained through the Hobbesian idea of the establishment of the commonwealth and sovereign. The integration of Socialist Core Values into socialist rule of law legitimates the moral authority of the almighty Party. In addition, the inclusion of democracy, fairness, and freedom in the Socialist Core Values suggests the Party considers that these values are not the exclusive hallmark of a liberal democracy. The assertion here is that the CCP is capable of building a comprehensive value system by offering an alternative to the so-called universal values as proclaimed by the West. This requires establishing the moral legitimacy of an authoritarian “China Model” as an alternative to liberal democracy.

The two-pronged argument offered here highlights the hybrid pan-moralist nature of the current ideological push: that is to say, it draws to our attention the ideological thinking that undergirds the claim that Socialist Core Values and law are mutually inclusive and “integrated.” Particular to China, this hybrid pan-moralism incorporates a Confucian–Legalist framework into the Hobbesian idea of an undivided and unlimited sovereign power. The virtuous “commonwealth” as conjured by Party theorists lays claim to both legal and moral authority. Such a claim circumscribes the entire moral landscape of the nation and society—including the attitude and behaviour of the individual—within the parameters deemed by the Party to be China’s core values. In other words, the ideological assertion that the Socialist Core Values and “rule of law” are compatible and complementary gives the Party the power and authority to use the law as a vehicle for consolidating and reinforcing the moral doctrine prescribed by the Party, hereby cementing supremacy of the Party over the law in legal and judicial decision-making processes.

Here, the key connector between the Party, the law, and Socialist Core Values is the will of the people. More than at any other time in the last 40 years, the Party under Xi Jinping today emphasizes the claim that it represents the will and interests of the people. This claim is important to the rationale that it must—by dint of the fact that it represents the will of the people—lead in all areas of governance, most notably the law. The law is an essential component of Xi’s ideology in the new era and Socialist Core Values play an essential role in connecting the will of the people with the capacity of the Party to govern over everything. According to Party propagandists, Socialist Core Values incorporate the “‘highest common denominator’ (zuida gongyueshu) of the values of the people of all ethnicities within the nation.”Footnote 20 As such, all legislation and judicial activity must, according to the above logic, embody these values within the law to bring out the true nature of the law (as reflecting the will of the people through the leadership of the Party). This amalgamation of law and Socialist Core Values helps the Party to further cement the concentration of its power under Xi.

Based on the argument presented above, the following will examine how and why the Party urges its judicial functionaries to conflate legal and moral decision-making. We consider evidence of this conflation as Party doctrine in the form of published “typical cases” issued in 2016 by the Supreme People’s Court (SPC), the highest court of the People’s Republic of China, as a means of promoting the Socialist Core Values.

3. NEW ERA PAN-MORALISM: AN ACCENTUATION OF THE CONFUCIAN–LEGALIST PARADIGM

In Western legal theory, the relationship between law and morality is complex. Furthermore, when we assess the view of any particular legal philosophy concerning the relationship between the law and morality, we find that, rather than whether a particular stance or theory considers jurisprudence as value-free or value-laden, the central issue is whether law and morality are conceptually distinct or inextricably intertwined. The position taken by a given theorist on this issue is first of all determined by her or his conception of law and morality.Footnote 21 It will be useful to keep these points in mind when considering Chinese legal culture and the presence of Socialist Core Values in contemporary law, discussed below.

Law and morality were both of paramount importance to Confucianism and Legalism, the two most influential competing political philosophies in China during the war-ridden Spring and Autumn and Warring Periods (ca. 770–221 bc). While both systems centre on the problem of order, each proposes a very different architecture for maintaining that order.Footnote 22 Each also proposes a different view on morality. Legalism is often considered to be a doctrine that rigorously excludes moral considerations from its penal code to focus instead on harsh punishment for even trivial transgressions.Footnote 23 The fundamental Legalist text, Han Fei Zi, written by the Legalist founder Han Fei Zi (ca. 279–233 bc), interestingly and somewhat surprisingly, includes an extensive discussion that suggests a Daoist stance towards morality. To Han Fei Zi, morality is expressed by the body and soul acting in unison and is achieved by being devoid of desire. It is further maintained by not contemplating morality, and strengthened by not deliberately performing morality.Footnote 24 Quoting the Daoist scripture Dao De Jing, Han Fei Zi argues that the more one claims to be moral, the less moral one is, while the less one claims to be moral, the more moral one becomes.Footnote 25 From this perspective, Han Fei Zi rejects the core Confucian notion of li, decorum, and ritual proprieties, as nothing more than a theatrical display of superficial human feeling that destroys genuine loyalty, integrity, and inner disposition, and which, therefore, produces nothing but chaos.Footnote 26 It is from this Daoist position of morality that Han Fei Zi develops his Legalist notion of governance.Footnote 27 Once the universal rules are set out and the authority of law established, argues Han Fei Zi, people will curb their desire to break the law and, since there will no longer be any need for punishment, people will then be able to live a moral life.Footnote 28 Morality, to Han Fei Zi, is a free expression of the inner sphere of attitudes and emotions. Law, on the other hand, is separate from morality and is a system of enforceable rules designed to regulate human behaviour. Han Fei Zi holds that, since human actions are driven by self-interest, these actions cannot be changed by education or other remedial measures.Footnote 29 A sovereign, therefore, should not lead through moral aspirations, but by balancing the interests of the subjects and the ruler through the enforcement of standardized rules that are equally applicable to all. As Geoffrey MacCormack rightly observes, the Legalist spirit very much lies in the importance attached to consistency and uniformity in applying the law.Footnote 30 Han Fei Zi’s rationale for a “Legalist” system of reward and punishment is simple—while human beings enjoy being rewarded and will continue to do what brings reward, they hate being punished so they will curb behaviour that results in penalties. To ensure compliance, furthermore, rewards must be abundant while severe penalties are necessary to deter non-compliance.Footnote 31 Han Fei Zi has no trust in “smart” government officials who would abuse their power and use the resources at their disposal to satisfy personal and family desires before serving the public interest.Footnote 32 Therefore, he calls for absolute power and authority to be bestowed on the ruler in order to equip those who rule to tackle fraud and deception by canny officials who appear to be prudent.Footnote 33 The Legalist rule of law, therefore, is not based on self-preservation, nor is it aimed at preventing a violation of the rights of individuals or groups. Its purpose, in fact, is to protect the sovereign’s interest from being undermined by the evil that arises from the selfish side of the human soul.

Confucianism, on the other hand, takes a different approach to morality. While Daoism is based upon contemplation of the natural law, the dao, without enforcing any mode of behaviour or imposing any predisposed moral principles,Footnote 34 the Confucian sense of morality arises from the normative design of a “universal” moral system. Since Confucians understand this design to be the restitution of the natural disposition of the human being and the natural hierarchical order of human relations within a family that, in turn, brings peace and order to an otherwise chaotic human society, they regard this system as impervious to critique. Mencius, a key Confucian canonical text, gives for example a lengthy discussion of the theory of heartmind (xixing). This theory, devised by the eponymous Mencius, postulates that the cardinal virtues and moral principles of benevolence (ren), righteousness/justice (yi), decorum and ritual proprieties (li), and prudence (zhi) derive from internal and inherent dispositions in human nature.Footnote 35 According to Confucian theory, the development of moral virtues is merely a matter of following the natural tendency of the social being. These moral virtues, furthermore, while essential for personal development, are more importantly the very key to governance and the maintenance of social order. Penal codes, according to this logic, are open to suspicion, since they subject the people to deception and argument.Footnote 36 In the Confucian ideal, the ruler is constructed as a saintly moral figure who, by virtue of his very position as ruler, becomes the nation’s moral teacher (junshi heyi). This logic established the Chinese political cultural norm that a mandate to rule relies on the moral authority of a regime. In other words, political legitimacy and moral authority are two sides of the same coin.

Both Legalism and Confucianism have long-standing status in China’s statecraft and one should not underestimate their combined influence on contemporary Chinese politics and society. The Legalist doctrine, adopted as the exclusive ideology of the First Emperor of Qin, assisted in the subjugation of all rival states that led to the establishment of the Qin dynasty (221–206 bc). This saw the beginning of over 2,000 years of an imperial system of government characterized by the absolute control of a supreme central authority. When the violent nature of the Qin dynasty led to its ultimate downfall, however, there was a gradual revival of the Confucian School during the Han dynasty that followed the Qin. Eventually, Emperor Wu of Han (ca. 140–87 bc) formally adopted the Confucian cannon as the state orthodoxy that remained in the ascendency throughout imperial China until the Republican Revolution in 1911.

As sociologist Zhao Dingxin points out, the political legacy of this historical trajectory is the resilient and persistent Confucian–Legalist state.Footnote 37 This state is characterized by an amalgam of political and ideological power with the meritocratic selection of officials who administer the country using a combination of Confucian ethics and Legalist regulations and techniques.Footnote 38 Tung-Tsu Ch”ü refers to imperial Chinese jurisprudence as the “Confucianization of law,”Footnote 39 while Bodde and Morris note “the incorporation of the spirit and sometimes of the actual provisions of Confucian decorum and ritual proprieties [li] into the legal codes.”Footnote 40 These observations confirm how the many rules of the various penal codes worked to reinforce the moral principles and related conduct regarded by Confucian orthodoxy as essential for the maintenance of order both within the family and society at large. Legal theorist Yu Ronggen similarly refers to the traditional Chinese legal system as “Confucian Moral Law” (rujia lunli fa), defined as a type of polity and law that is guided by Confucian ideas grounded in genetic kinship relationships and which considers customary moral norms to be the spirit and soul of the law.Footnote 41 The fundamental defect of this traditional legal system, Yu argues, lies in its strong tendency towards pan-moralism—that is, in its willingness to accord supremacy above the law to prescribed moral principles.Footnote 42 As Bodde and Morris point out, one consequence of this Confucianization of law is the differentiation in the legal treatment of a case depending on the social or familial status of both the suspect and the victim. Precisely because moral judgements, especially those based on kinship relationships, are subjective and particularistic, the interpretation by decision-makers of the particular circumstances under which a crime is committedFootnote 43 is inevitably influenced by factors such as the status of the offender and/or the victim.

Many scholars within China have criticized as problematic this intertwinement of law and morality embedded in Chinese legal thought. While new Confucian philosopher, Mou Zongsan, warned that an effort must be made to pry apart moral and political values to prevent politics from being consumed by morality,Footnote 44 Liu Zuoxiang regards the conflated relationship between law and morality as a hindrance to China’s journey toward a rule of law.Footnote 45 Liu argues that moral judgement must not replace legal judgment in the implementation of the law, and that law and morality must be kept at a distance from one another.Footnote 46 Sun Li argues that promoting moral principles through the means of the law merely results in law and morality “sacrificing” each other in a manner that destroys both the authority of the law and one’s freedom to act as an autonomous and rational moral agent.Footnote 47 Sun further points out that both traditional law-based governance (Legalism), which emphasizes punishment, and virtue-based governance (Confucianism), which emphasizes education and transformation, are based upon an instrumentalist view of law and morality that aims to sustain the state by converting individuals into servile and submissive subjects.Footnote 48 She argues that this instrumentalist view of law and morality conflicts with the modern concept of rule of law aimed at protecting social freedom and human rights and also with the modern concept of morality that values free will and autonomous decision-making.Footnote 49 Ji Weidong, who provides a thorough analysis of the fluid nature of the justice system in China, goes one step further to declare the system to be suffering from the “balance trap” of Confucianized legal thought patterns.Footnote 50 These thought patterns have created a dialectical governing technique that, by merging particular situations with particular emotions, and common understandings with stipulations of law (qing, li, fa) in the judicial decision-making process, places dual emphasis on law and morality.Footnote 51 As a result, rather than a process that seeks a definitive judgment through reasoning, justice becomes an ever-expanding and ever-changing process of bargaining, negotiating, and mediation that aims to reach the most suitable balance point (hence the term “balance trap”).Footnote 52 Ji argues that this has led to the absurd situation of a highly centralized but weak power structure on the one hand and a people who have no respect for, yet are submissive to, the law and regulations on the other.Footnote 53 According to Ji, in order to avoid an ongoing downhill slide into this sort of “trap,” the fundamental task of political reform should be to re-shape the nature of power and authority in order to reduce the complexity and uncertainty of the legal system. In short, Ji advocates for the construction of judicial independence and the modern Western rule of law.Footnote 54

In contemporary times, the ongoing and deep-seated influence of China’s ancient law–morality dialectic has resulted in moral cultivation remaining high on the party-state agenda. This agenda, inscribed as it is with moral principles, has previously been brought to the fore in civilizing campaigns such as the “five stresses and four goods”Footnote 55 and the “four haves.”Footnote 56 In his seminal work on the concept of man in traditional and contemporary China, Donald Munro sees much convergence between the Chinese Marxist and Confucianist understandings of the malleability of the social nature of humans.Footnote 57 The remodelling and reshaping of a new socialist person has not, however, been free from punitive measures. Reflecting the Legalist strategy of social control, the Party’s civilizing campaigns have always coupled the idea of granting rewards for compliance with exerting harsh punishment for transgressions.Footnote 58 Historian Qin Hui argues that, if imperial society in China was Confucian on the surface and Legalist at the core (rubiao fali), contemporary society can be seen as Marxist on the surface and Legalist at the core (mabiao fali).Footnote 59 Qin points out that, although the moral and ideological principles may have shifted from a Confucianist to Marxist paradigm, the subordination of the individual, to filial obedience in imperial times and to the nation under socialist rule, remains unchanged. Thus, in China, there has been an enduring tendency towards tyranny that, to a greater or lesser extent, resembles the tyrannical Legalist regime of the Qin dynasty.Footnote 60

As scholars such as Stephen Angle have demonstrated, virtue politics is certainly not new to CCP governance strategy, particularly in the late 1990s, when Jiang Zemin first espoused the idea of “governing the nation by morality” (yide zhiguo) alongside “governing the nation in accordance with the law.”Footnote 61 However, the manner in which the Xi Jinping administration has deployed the principles of virtue politics in its efforts to justify bringing the Party leadership as close as possible to the state takes this vision well beyond the party-state relationship envisaged in the 1990s. Sharpening the Party’s ideological articulation of the ethos of rule by morality has required a process of value-adding to the existing ideological storyline. From this perspective, Xi Jinping has taken this catchcry to new ideological heights by insisting that, since the two are complementary, there must be an “organic integration” of yide zhiguo and “governing the nation in accordance with the law” (yifa zhiguo). Asserting harmony between law and morality in this way enables Party leaders to promote a particular chain of thinking that binds together and “organically unifies” (youji tongyi) what might otherwise be read as dissonant concepts or statements. Party legal theorists, such as Xu Xianming, have also given strong support to this process of unifying thinking. For instance, in a July 2017 paper on the necessity of combining rule of law and rule of morality, Xu notes the explicit requirement by Xi Jinping that leading cadres model good moral virtue:

Good governance primarily depends on the conduct of the people who engage in administration. It is critical to create a good environment for the rule of law and [a] moral atmosphere so leading cadres can set an example and lead their subordinates. General Secretary Xi Jinping has pointed out that leading cadres should not only be important organizers and facilitators for the comprehensive rule of law, but also active advocates and demonstrators of moral construction.Footnote 62

As we will outline below, one of the key means of demonstrating good morality is by correct legal decision-making that purportedly reflects Xi Jinping’s Socialist Core Values. These are values that clearly share commonalities with previous civilizing campaigns that have aimed to transform citizens for nation building. First promoted at the 18th Party Congress in November 2012 marking the rise of Xi Jinping to the leadership of the CCP,Footnote 63 these values, which, as noted in the opening comments of our argument, draw on the three levels of individual, society, and nation, echo the same sociological assumptions that underpin the Confucian political paradigm. This assumption, in short, is that the transformation and refinement of the self and the individual form the one precondition and only pathway to social transformation and national prosperity.Footnote 64 As outlined earlier in the paper, in the political sphere, this becomes the presentation of the ruler and the ruled as a “unitary construct,” with the people emulating the exemplary moral virtues of the nation’s leaders.Footnote 65

When compared to other morality campaigns, however, the distinguishing feature of the promotion of the Socialist Core Values is that, for the first time, the sanctioned moral principles have been incorporated by a government directive into the legal realm. In spite of the fact that this explicit conflation of law and morality is contrary to warnings, cited above, given by scholars such as Ji Weidong, it is the unequivocal stance that the Xi Jinping administration has chosen to adopt. It is also a stance that permits the Party’s moral authority to rule above the law.

The first government directive that focused specifically on the Socialist Core Values was issued by the CCP Central Committee in 2013. Entitled “Opinions on Cultivating and Practising Socialist Core Values,” this document required Socialist Core Values to be integrated across the full range of administrative processes, such as civil education, economic development, social governance, and media and propaganda, and also across various types of social activities and all levels of administrative and other leadership. In addition, under the subheading of social governance, the Socialist Core Values statement featured a paragraph stipulating that these ideals were to be implemented into the country’s administrative and governance practices in accordance with law, by “using the authority of law to cultivate and practise the self-consciousness of Socialist Core Values.”Footnote 66 As in the Confucian–Legalist state, this political logic sees the law become subordinate to and serve the sanctioned moral principles, both concepts of which are embodied in the leadership of the Party.

The historic October 2014 Decision of the CCP Central Committee’s Fourth Plenum of the 18th Party Congress was the first government directive in the history of the People’s Republic of China to focus exclusively on “governing the nation in accordance with the law.” For the first time, also, the statement exalted the leadership of the CCP as “the most essential trait of ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’” and as “the most fundamental guarantee for Socialist rule of law.”Footnote 67 In this sense, Party leadership and the socialist rule of law here become entirely complementary with explicit dual emphasis placed upon governing the country in accordance with the law and also upon governing the country in accordance with moral principles.Footnote 68 This proclamation has clearly set the ideological groundwork for subsequent declarations relating to the law–morality dialectic.

In October 2015, the SPC responded to the 2014 Decision by issuing “Opinions on Cultivating and Practising Socialist Core Values at People’s Courts.” Repeating the Decision’s statements on Party leadership, the SPC Opinions further state that “all judges and other court personnel must ensure a high degree of uniformity in thought and action with the CCP Central Committee and Xi Jinping as the General Secretary.”Footnote 69 In December 2016, the CCP Central Committee and State Council followed this up by issuing “Guiding Opinions on Further Integrating Socialist Core Values into the Construction of Rule of Law” (Guiding Opinions), which called for party-state functionaries to turn “soft” moral principles into “solid, binding legal rules.”Footnote 70

The Guiding Opinions detail the modelling of the Socialist Core Values in the legal realm in five respects. First, they instruct functionaries to incorporate the spirit of Socialist Core Values into the law. The Guiding Opinions state that “the requirements of the Socialist Core Values must be reflected in the Constitution, laws, rules and regulations and public policies.”Footnote 71 They add that emphasis must be placed on converting basic moral norms and effective policies into laws and regulations to promote the legislation of civilized behaviour (wenming xingwei), honesty and integrity (shehui chengxin), good Samaritan behaviour (jianyi yongwei), reverence for heroes (zunchong yingxiong), volunteer services (zhiyuan fuwu), frugality (qinlao jiejian), and respect for parents and the elderly (xiaoqin jinglao). There is also a call to improve the capacity of making specific laws in cities containing district governments.Footnote 72 Second, this document requires functionaries to reinforce the value orientation of socialist governance by advocating and encouraging behaviour that is in conformity with the Socialist Core Values and restraining and punishing behaviour that contravenes the Socialist Core Values. In order to do this, administrative leaders are called up to merge particular situations with particular emotions, and to merge common understandings with stipulations of law (qing, li, fa) in legal and judicial processes.Footnote 73 Third, the document asks functionaries to use “judicial justice”Footnote 74 to guide social justice by allowing the people to feel that fairness and justice has been applied in each and every judicial case. One means of achieving this is by publishing exemplar court cases that cultivate and promote the Socialist Core Values as models to ensure the standard application of the law.Footnote 75

Fourth, the Guiding Opinions require functionaries to promote and nourish the spirit of socialist rule of law by harnessing the moral foundation of the rule of law and integrating moral teaching into law dissemination and education. Furthermore, they direct cadres to deepen education in areas such as public social morals, professional ethics, family virtues, and individual character, and to promote patriotism, collectivism, and socialist thought.Footnote 76 Fifth and finally, the document asks functionaries to strengthen organizational leadership by reinforcing the ideological and political qualities (suzhi) and the professional expertise and ethical standards of legal personnel as a means of ensuring that they are loyal to the Party, to the nation, to the people, and to the law.Footnote 77

This rhetoric extolling the five aspects of the rule of law outlined above as processes that integrate the legal system with moral principles demonstrates an assumed incontrovertible amalgam between law and morality that resembles the pan-moralism practised by successive imperial regimes. As in the Confucian–Legalist imperial state, morality here is treated in a particular normative sense whereby claims are made about the unified nature of socialist values held by China’s rulers and the ruled. No regard is given to any alternative reality that might operate in a diverse and heterogeneous society characterized by complex moral values. In other words, morality becomes an ideology that demands not mere compliance, but complete unity of thinking between the Party and the people it governs.

Following the issuing of the 2016 Guiding Opinions, both the SPC and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate (SPP) published statements detailing the way in which functionaries in these organizations would work to integrate law and morality into everyday case-loads.Footnote 78 As argued earlier in the paper, xiang jiehe, or “integration,” is a particularly important concept in reinforcing the rule of law and rule by moral virtue dialectic. In April 2017, SPC Deputy President and Vice Party Secretary Shen Deyong published an article reiterating the key points of the 2016 Guiding Opinions and the importance of integrating governance through moral virtues with the socialist rule law.Footnote 79 He called for unification of thought in order to fully understand the significance of integrating the Socialist Core Values into the construction of the rule of law.Footnote 80 Judicial functions, he noted, should be used to promote Socialist Core Values. For example, fair trials must be carried out to resolutely combat behaviour that distorts the history of the Party and that denies the fine tradition of the Party and the People’s Army.Footnote 81 Here, the law is portrayed as contributing to the armoury against behaviour that would challenge Party credibility.

In April 2017, the SPP issued a notice demanding that, as the soul of the socialist rule of law, Socialist Core Values must be integrated into the entire judicial process.Footnote 82 Integrating Socialist Core Values into the legal and judicial realms manifests a new traditionalism in the official approach to law and morality, law, and politics, which allows no space for meaningful discussion of an alternative vision of rule of law marked by concepts such as judicial independence—a vision that has support of many legal scholars inside China. It is, however, consistent with the vision of establishing the absolute power and authority of the Party, the judgements of which shall be counted as the individual’s own. This is the rationale by means of which autonomous moral agency and pluralistic individual judgements relating to the social and political lives of the people must be renounced. When the power of the Party is absolute and its judgement without fault, the will of the individual is rendered obsolete.

In order to fully understand the contemporary articulations of the imperial Confucian–Legalist state in the context of this Xi Jinping’s law–morality push, we might remain cognizant of the Party’s message that its own moral supremacy gives it the authority to correctly judge and shape the morality of its citizens through legal means. Below, we provide a number of concrete exemplars published by the SPC outlining how the morality-law amalgam should be implemented.

4. CLAIMING MORAL AUTHORITY THROUGH LAW: TYPICAL CASES FROM THE COURTS

People’s courts in China have a politico-educative function. Through their routine legal functions, people’s courts assume a political responsibility to implement directives from the Party and the stateFootnote 83 and a moral responsibility to raise the moral standard of the entire society.Footnote 84 The CCP Central Committee’s issuing of Opinions (2013)Footnote 85 and Guiding Opinions (2016),Footnote 86 as outlined above, has given Socialist Core Values the status of government policies. Liu (Reference Liu2016) notes the following in an official news report:

As the trial organ of the nation, the people’s courts bear primary objectives to enforce law, handle cases, arbitrate disputes, reward the good and punish the evil, while also preserving righteousness. It is the People’s court’s duty-bound obligation to carry forward Socialist Core Values and to propel the entire society forward to continuously improve the standard of constructing Socialist Core Values.Footnote 87

How do the Chinese courts implement Socialist Core Values into their decision-making process? Are these moral principles empty rhetoric or are they affecting the courts’ everyday practices? The politico-educative function of people’s courts requires Socialist Core Values to be implemented through a top-down process. In response to the CCP Central Committee’s Opinions (2013)Footnote 88 and Guiding Opinions (2016),Footnote 89 the SPC has published guiding principles and “typical” or “representative” cases (dianxing anli) as a guidance for inferior courts to embed Socialist Core Values in their judgments.

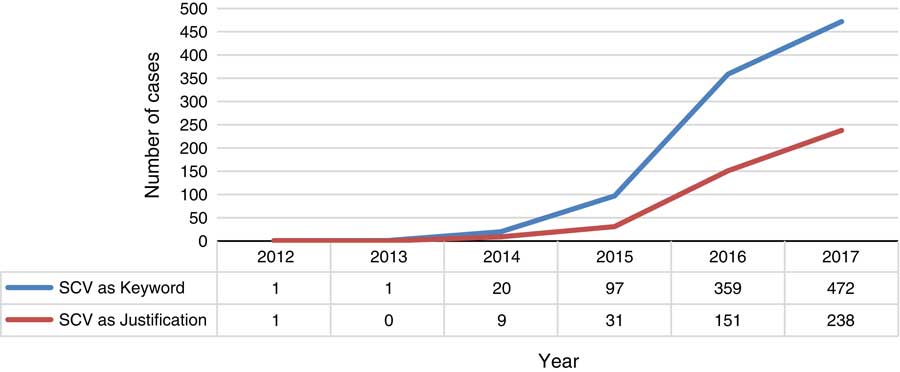

Typical cases have long been used to implement public policies. Since the 1950s, the SPC has published model cases as a guidance mechanism designed to assist the courts with the interpretation of new rules, new laws, or new judicial practices. In more recent decades, the cases are also published in national newspapers such as Legal Daily to educate the public.Footnote 90 As discussed above, in October 2015, the SPC issued “Opinions on Cultivating and Practising Socialist Core Values at People’s Courts.” In March 2016, the SPC published ten typical samples of actual court cases that promoted the Socialist Core Values.Footnote 91 A search on the China Judgements Online (zhongguo caipan wenshuwang)Footnote 92 indicates that, since 2015, the number of cases where Socialist Core Values have been embedded in case judgment remarks has been dramatically increased, as is denoted in Figure 1. In 2014, only 20 cases published on China Judgements Online used Socialist Core Values as a keyword, nine of which quoted it as an argument for the court’s decision. By the end of 2017, this number had jumped to 472, of which 238 cases quoted Socialist Core Values in their decision-making rationale.Footnote 93

Figure 1 The use of Socialist Core Values in court cases (2012–17). Source: based on data retrieved from China Judgements Online (https://wenshu.court.gov.cn) on 9 October 2018.

Liang and Wang have conducted an analysis of 352 cases uploaded onto Chinese Judgements Online from 2012 to 2017 that have quoted Socialist Core Values as an argument for the court’s decision.Footnote 94 They find that the vast majority of the cases are from the lowest-level local courts (255), followed by the intermediate courts (72), provincial-level high courts (25), and none from the SPC. Six forms of values are promoted from these cases: credible and trustworthy social relations; harmonious and friendly social atmosphere; a positive and healthy culture; customary morality to maintain social order; equality between social members; and faithful obedience to law.Footnote 95

The task of embedding Socialist Core Values into legal reasoning is in its infancy. The online judgments are general, in some cases superficial, and in other cases problematic. Liang and Wang have listed four problematic techniques used by the courts to implement Socialist Core Values as demonstrated in these cases: (1) mechanically quoting the core values with no substance, (2) exaggerated claim of the moral and political standpoint in decision-making instead of making a carefully constructed legal argument, (3) losing the true values behind the law by avoiding real problems to reduce the risk of violating the core values and (4) the implementation being limited to petty cases only, yet serious and complex cases involving conflicts in values and interests still remaining unresolved.Footnote 96

As we shall demonstrate below, the ten typical cases published by the SPC in 2016 indicate similar techniques and forms of values promoted. Zhang argues that the SPC typical cases aim to go beyond providing general guidance for inferior courts; rather, they exist to establish an authoritative principle or rule for future judgments.Footnote 97 All the ten cases are selected from the district level—that is, the lowest-level local courts. None of these are from higher courts. Hence, they are explicitly aimed at changing legal culture at the grassroots. The titles of the ten cases are as follows:

1. Dispute of 12 village residents Zheng XX inclusive being sued by the village committee for return of properties.

2. Labour dispute involving Zhang XX being sued by a tour & hotel company in Yichun.

3. Fraud committed by Qiu X Liang.

4. The sale of fake commercial brands using closed Wechat groups.

5. Companies including Aimeide sued by a Travel Satellite TV for breaching logo copyright.

6. Dispute relating to the general hospital of an industry group applying medical service; contract to evict Chen X Chun.

7. Dispute relating to property owner Deng XX being sued by a body corporate for breaching a property service contract.

8. Dispute relating to Tang XX suing five children for financial support.

9. Dispute relating to Deng XX suing a courier company and a recruitment company for breaching the right to general human dignity.

10. Dispute between Hua Bo and Wang Shibo, Wang Xiquan concerning right to life and execution of court decision.

Each typical case judgment contains three sections: a summary of the case, the court orders and judgment, and the exemplary value implications. The forms of values promoted include credible and trustworthy social relations and behaviour (six times), customary morality to maintain social order including family virtue of supporting elderly parents (twice), friendliness and helpfulness (once), honest obedience to law (once), and gender equality (once). These constitute five of the six forms of values promoted in the 352 cases studied by Liang and Wang, showing that the ten typical cases have presented model categories of values to be promoted through the judicial process. Below, we discuss two of the ten cases in order to highlight the techniques used by the courts in meeting their obligation to promote the supremacy of Socialist Core Values.

The first exemplar involves a dispute arising from housing demolitions and relocations during the process of “constructing the new countryside.” The case is summarized in the published document as follows:

Zheng and the other 11 villagers were taken to court for changing the locks of 12 new apartments yet to be allocated and occupying these apartments. The village passed the relocation plan and resolutions. In accordance with the relocation plan and resolutions, the houses of the twelve accused villagers were demolished and the residents allocated new apartments. The twelve villagers stated that they occupied the additional 12 apartments for the following reason: as the first group being allocated new apartments by the relocation plan, they were the only ones required to follow the objectives of the plan. For the subsequent groups the relocation plan was never properly observed. Some villagers were allowed to build single-level stand-alone houses on the same premises of their previous property; some were allocated with apartments larger than the size stipulated by the relocation plan; some did not need to pay the expenses as per the plan’s requirement; some had shifted their household registration from the village but were nonetheless allocated new apartments; some village cadres breached the relocation plan. The twelve villagers therefore refused to return the keys for the 12 additional apartments they occupied.

Ruling that it was illegal to occupy real estate owned by other parties, in this case the community of this village, the court ordered the 12 villagers to vacate the occupied properties within ten days. The court further ruled that the complaints of unfair practice cited by the villagers should have been reported and dealt with through the proper channels. The court promised to write to the village’s higher authority to inform them of the unfair practices reported by the plaintiffs and to encourage the higher authority to investigate and deal with the situation in due course. In the exemplary value implication section, the 12 villagers were accused of dishonesty and of not respecting rule of law—a violation of two Socialist Core Values (i.e. the social value of rule of law and the individual value of integrity). The case exemplar summary states:

This case is to educate and warn those who commit acts against the law during the construction of the new countryside, in order to guarantee the standard progress of new countryside construction. During this construction process, some villagers with weak legal consciousness, who think they can take chances, show no respect for the law and thus neglect the various laws, acts, regulations and rules within a village. Often acting as a group, they attempt in vain to gain illegal or inappropriate benefit through unlawful means and thus cause great damage to new countryside construction. The judgement of this case demonstrates that one ought to abide by the spirit of contract during the process of constructing the new countryside. By cracking down on the illegal occupation of properties and acts that violate rules and promises, this case removes such obstacles to the construction of new countryside, preserves order and guarantees the smooth advancement of new countryside construction.

The value implication section of this exemplar can be read as a moral judgement against the plaintiffs whose moral behaviour is measured only against the principles of Socialist Core Values. No carefully constructed legal argument is given as to address, for example, the plaintiffs’ actual motivations for committing these acts. The judgment clearly implies the importance of submitting one’s autonomous moral agency to the single moral authority and agenda of the commonwealth, which in turn will preserve order and maintain smooth social development. Not only are alternate motivations (in this case, unequal treatment of villagers during the relocation process) that divert from state-prescribed moral principles not considered in the judgment; they are, in many instances, criticized or even actively condemned. In his analysis of 100 cases selected from a different database that implement Socialist Core Values, Meng (Reference Meng2018) concludes that three public-policy factors are pushed through the court orders and judgment. The first is national identity. Meng (Reference Meng2018) finds that, in the implementation of Socialist Core Values, judgments clearly place emphasis on protecting national and collective interests, promoting nationalism, and consolidating recognition of the proposition “without the Communist Party there would be no new China.” The second public-policy factor being promoted is social unity. In the cases involving disputes between neighbours, family members, and communities, harmonious family, family virtues including caring for the elderly, and being trustworthy are stressed in the implementation of Socialist Core Values. The last public-policy factor is individual rights; especially in the case of unequal status between the two parties, the court is encouraged to judge in favour of the disadvantaged party. The typical case examined above demonstrates an emphasis on the national agenda of new countryside construction in the decision-making process of the court.

The second example we draw on concerns a family dispute. Ninety-year-old Tang took his five daughters to court for refusing to provide financial parental support. Tang and his wife together received only RMB 200 (approximately $30 (US)) per month in aged pension payments from the government and had no other source of income. They requested their daughters pay RMB 1,000 per month to support their daily expenses and to share responsibility for their medical expenses. The daughters demanded a share in the land held in the names of their parents and the appointment of a fund manager as conditions of providing the requested support.

The court ruled that care of the elderly, including the provision of financial support, is a fine traditional virtue of the Chinese nation and is also the legal obligation of children. Children, it was argued in the ruling, have no right to make additional demands when fulfilling this obligation. The court therefore ordered that each of the five daughters unconditionally paid RMB 200 per month to their parents as per Tang’s request. The exemplary value implication in this case centred on family virtues. The section is outlined below:

Today the financial situation of the countryside is getting better and better, and government aged care policies are also becoming relatively comprehensive. In the countryside, however, disputes around providing for elderly parents still frequently occur, often due to the old notion that only sons are obliged to provide parental support. This creates the belief that, because daughters and sons-in-law do not carry family surnames, they are free from any responsibility towards elderly parents. However, the law stipulates that all children have an obligation to support their parents …. The court specifically chose the village cultural auditorium as the location for the hearing. Since this trial attracted the attendance of hundreds of villagers from local areas, it truly achieved educating the masses through one case.

Here, we see a clear example of how a court judgment serves both a legal and an educational purpose. The moral-reflection section of the case exemplar praises the government for providing sufficient care for its aged citizens, while blaming the family for failing to give sufficient support to these elderly parents. Thereby, both national identity and social unity are promoted through this court judgment and the single form of value stressed here is the traditional family virtue of caring for the elderly.

The publication of typical cases is only the tip of the Socialist Core Values iceberg. In September 2018, the SPC took one step further to issue a five-year “Work Plan to Fully Incorporate Socialist Core Values into SPC Judicial Interpretations (2018–23).”Footnote 98 This has opened up a new and very ambitious space for implementing Socialist Core Values in the judicial process. This requires SPC officials to revisit and revise hundreds of existing judicial interpretations in order to embed the core values into the guidance on how to interpret the law.Footnote 99

5. THE PARTY AND SOCIALIST CORE VALUES: CREATING A VIRTUOUS LEVIATHAN

In this final section, we focus not on the law–morality amalgam per se, but on the moral justification for the supremacy of CCP rule. In doing so, it will be useful to use the lens of Hobbesian political philosophy to further scrutinize the significance of the Party’s current promotion of the rule of law by moral virtue dynamic. It is clear that the Party’s promotion of Socialist Core Values sets out to justify the increasingly centralized supreme leadership of the Party over all aspects of governance in China. It is no coincidence that this has occurred at around the same time as the Party has amended its governing Constitution to include the lines “The Party exercises overall leadership [encompassing] all areas of endeavour in every part of the country,”Footnote 100 the literal translation of which reads: “Party, government, military, society and schools — north, south, east, west and middle — the Party leads all.” It is also no coincidence that this rule of law by moral virtue dynamic has reached its political height right at the time that the Party has announced the establishment of a new National Supervision Commission (NSC) that effectively merges all Party and state anti-corruption supervisory organs into one mega-organization, the role of which will be to monitor every employee of the state.Footnote 101 The NSC Law sits alongside moves to replace the people’s armed police under Xi Jinping’s direct controlFootnote 102 as well as security lawsFootnote 103 passed in 2015, which now enable direct Party leadership in vital areas of state governance (rather than leadership exercised through mere ideological or policy oversight by the Party). Importantly, the establishment of the NSC has been billed by Party propagandists as a means of “building high moral standards.”Footnote 104

As discussed in the previous section, the Legalist logic of an unchallenged central authority derives from an innate mistrust of officials and subjects, both of whom are seen as self-interested and prone to bribery and corruption. However, the dour nature of a purely Legalist explanation of Xi Jinping’s Party supremacy is difficult to reconcile with the attention paid at the 19th Party Congress in October 2017 to happiness and the livelihood of the people. In his report to this Congress, Xi Jinping declared that “principal contradiction” facing China’s socialist society is the tensions between “unbalanced and inadequate development and the people’s ever-growing need for a better life.”Footnote 105 Here, we can intuit that a purely Legalist approach fails to offer the necessary insight into the power relationship between the Party, Xi Jinping, and the people. Something more is required to explain satisfactorily the ideological justification for Xi Jinping’s strategy of strengthening centralized Party leadership in all aspects of law-based governance.

We noted at the outset how Kerry Brown has suggested the usefulness of the seminal Leviathan thesis proposed by Thomas Hobbes as a means of grasping the nature and inner worldview of the CCP and its relationship with power.Footnote 106 Apart from the obvious connection of the commonwealth and the CCP as the sole source of order and sovereign authority “to which to which individuals must give their allegiance,” Brown identifies two more parallels between the Leviathan and CPC rule:

First, Leviathan shows the risks of dissidence, and the existential threat it poses: not just for the commonwealth but for the principle of order itself … The need to locate power in one place remains vital for the party—witness its ruthless recent crushing of rights lawyers and non-government activists. Second, reading Hobbes’s masterpiece illuminates the way the CPC relates to power, and the contrasts with how political parties in multi-party systems operate. It has proved hard to find a conceptual framework that can figure out what the CPC’s power is. The CPC is almost like a state within itself, or its own world—an all-embracing social, cultural and ideological body. It does not submit itself to public elections, and yet it says it is the highest expression of the public will. It does not involve itself in the detail of administration and governance as such, but says it guides the core political and strategic matters of modern China.Footnote 107

Kane, on the other hand, sees Xi Jinping’s strategy best explained through the Hobbesian version of authoritarianism that “aims at taking contentious issues that threaten peace out of the civic sphere so as to allow citizens harmlessly to pursue their individual goals and material welfare.”Footnote 108

We concur with the ideas put forward by Brown and further suggest that the vision of commonwealth and sovereign developed by Hobbes can shed light on the role of the CCP and Xi Jinping in the design of New Era Socialism with Chinese Characteristics.

First, we might consider how the political notion of the Leviathan came about. Having witnessed the disasters and chaos of war, Hobbes argued that civil peace and social unity could only be achieved by erecting a Common Power, which he refers to as the commonwealth, as a means of ensuring common defence and common security against both invasion by outside foreigners and domestic strife within. To Hobbes, this commonwealth as an artificial “Person”—a colossal “human” form, a great Leviathan—built from the bodies of the citizenry. All citizens submit their will to its Will, and their judgements to its Judgement. In this sense, citizens relinquish the right to govern themselves to this “Leviathan” entity.Footnote 109 Passionately declared by Hobbes to be “more than consent, or concord,” the resultant commonwealth becomes “a real unity of [all citizens], in one and the same Person, made by the Covenant of every man with every man.”Footnote 110 The essence of the commonwealth, according to Hobbes, is One Person—a leader whose acts comprise those of the great multitude and who ultimately is the Author of the collective. And, to that end, by the means of centralized power and strength conferred to it and by terror thereof, the commonwealth can perform the will of all the people for their peace and common security.Footnote 111 For Hobbes, this “Leviathan,” this “sea monster” from the Hebrew Bible, ultimately becomes the definitive metaphor for the vision of perfect government. The head of the Leviathan is the sovereign who holds absolute power and who acts on behalf of the entire commonwealth.

Efforts by the 19th Party Congress to make Xi Jinping the unchallenged core authority are usefully explained in terms of Leviathan theory as proposed by Thomas Hobbes. In terms of this theory, the CCP becomes the commonwealth, the single ruling entity with supreme powers, while Xi Jinping, the all-powerful leader, becomes the sovereign. The CCP represents the interests of all the people, although the masters of the nationFootnote 112 concede the right of governing themselves to the rule of the CCP. In return, they receive a guarantee of common peace and prosperity. This is the Hobbesian notion of the social contract.

Some readers of Hobbes, however, had doubts that the people, the so-called subjects, would relinquish their free will to commonwealth. This is because, in the Hobbesian narrative, there is no justification for the political legitimacy of the Common Power other than the promise of a safer existence for all. This conundrum, however, is circumvented by the designers of Xi Jinping’s “new era” of Chinese socialism by the Party’s adoption of a pan-moralist stance that draws from the traditional fund of political ideas related to the law–morality dialectic. The CCP claims that its leadership embodies the Socialist Core Values, which represent the highest values of the state, and which the Party, the society, and the individual each upholds. This self-proclaimed moral authority defines its own political legitimacy and allows the Party to declare unity with its people at a time in history when the Party is shifting ever closer to and looking to merge more completely with the state. This shift is evident in the publicity rhetoric deployed by Party leaders in relation to the newly established NSC referred to above. According to Yang Xiaodu, deputy secretary of the Party’s Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), this new mega-structure will “organically unify” (youji tongyi) the Party’s internal disciplinary and inspection mechanism on the one hand and state governmental supervisory structures on the other. In conceptual terms, according to Yang, the Commission will “organically unify intra-party law with [the idea of state] governance in accordance with the law.”Footnote 113 The creation of this Commission provides an unprecedented opportunity for the Party to concentrate its power.

As a legal positivist, Hobbes needed to assign the systemic validity of law to its promise of keeping the peace. In other words, he realized that moral demand alone may not be sufficient justification for obedience to law. This, however, is not the case with Xi’s “new era” Chinese socialism. To assume unchallenged powers and political legitimacy, the Party has made a claim to absolute moral authority through all means and processes of the law. This is the essence of the current “rule of law by moral virtue” phenomenon. This claim to absolute moral authority, we argue, complicates a mere Hobbesian explanation of Xi Jinping’s strategy. While Hobbes is characterized as a liberal philosopher who defends individual liberty, Xi’s vision of “new era” socialism is not to adopt any form of liberalism.

6. CONCLUSION

In this paper, we propose that the significance of Xi Jinping’s political strategy of New Era Socialism with Chinese Characteristics as a moralizing governance concept can be best understood when examined through a double lens. The first involves the vision of commonwealth and sovereign as proposed by Thomas Hobbes, while the second relates to imperial pan-moralism and the notion of the morally virtuous leader as embedded in the indigenous Chinese tradition of the Confucian–Legalist state. One lens alone is not sufficient to grasp the modern and pre-modern elements of the political strategy being deployed by the Xi leadership. While Hobbesian ideas relating to the commonwealth and its sovereign provide insights into the claim to supremacy by the Party and the Xi Jinping leadership, they do not explain the current campaign relating to virtuous leadership. For insights into this aspect of the current administration, we must look to notions of pan-moralism as this has played out over millennium in the Confucian–Legalist state. In bringing together these lenses, the modelling of Socialist Core Values in the legal realm can be seen as part of a holistic political strategy that we label as a “virtuous Leviathan.” The CCP as the commonwealth claims not only unmitigated central power capable of securing and maintaining order, but also supreme moral authority that requires all citizens to submit their will and right to govern themselves to the single entity of the Party. The ultimate purpose is undisputable: the CCP led by Xi Jinping is determined to create a new model of governing that rejects the principles of Western liberal democracy. Xi refers to this model as New Era Socialism with Chinese Characteristics. According to Party perceptions, this approach to governance not only delivers social order, but also guarantees a viable alternative to the harmony, freedom, and democracy promised by a liberal democratic governance model. To Chinese leaders, while this new model is politically feasible and sustainable, it also guarantees the perennial rule of the CCP. There are, however, two challenges to the long-term success of this model. First, the CCP needs to convince its own social elites who do not share this vision of placing power above the law and into the hands of the “core leadership” of Xi Jinping of the worth of this model of New Era Socialism with Chinese Characteristics. The recently drafted supervision law, for example, has elicited criticism from Constitution and criminal justice scholars such as Han Dayuan,Footnote 114 Chen Ruihua,Footnote 115 and Chen Guangzhong.Footnote 116 Second, and more importantly, placing the CCP on the highest moral pedestal and demanding submission of citizens to the will of the Party are at odds with the growing rights consciousness of the general public, who remain unmoved by the Party tactic of labelling those members of the general public who have developed such a consciousness as the “low-end population” (diduan renkou). How the CCP resolves these challenges remains to be seen and will surely be the topic of future research.