Introduction

Over the last half-century plea bargains or ‘trial-avoiding conviction mechanisms’ have progressively occupied a crucial place in global criminal justice systems.Footnote 1 Across today's Anglo-American and Continental jurisdictions, the idea that prosecutors and defendants negotiate and reach consensus on charging and sentencing concessions in exchange for guilty pleas is neither innovative nor heretical.Footnote 2 This occurs so often that plea bargains have become more common and more important than criminal trials.Footnote 3 In the US, for example, more than 95 per cent of criminal cases are now disposed of through negotiated pleas in its over-burdened criminal justice system.Footnote 4 Similarly, criminal verdicts reached through agreements have exponentially increased in the judicial process of many civil law countries.Footnote 5 The so-called ‘Americanisation’ of legal systems has seemingly influenced this move;Footnote 6 but the adoption of plea bargaining in countries like, inter alia, Germany, France and Italy unfolds a vastly divergent route of prosecutor-defendant negotiations that dovetails with local conditions of inquisitorial criminal procedure.Footnote 7

On the other side of the world, China's receptivity to mechanisms that allow the defendant to enter a guilty plea in pursuit of particular benefits has been deeply entrenched in the country's distinct criminal justice culture. Since its inception in 1979, China's Criminal Law has been committed to encouraging defendants to confess or admit guilt.Footnote 8 While doing so typically amounts to a mitigating factor in sentencing, since 2012 it has also justified the dispensation of abbreviated court proceedings where the judge is permitted to adjudicate the criminal case in an administrative fashion based on the agreed summary of facts presented.Footnote 9 This alternative to fact-finding hearings was later reformed and incorporated into China's overarching policy of ‘Admission of Guilt and Acceptance of Punishment’ (Renzui Renfa Congkuan, ie, ‘Plea Leniency’), which was devised to formalise and standardise the approach to guilty pleas in the criminal process. In the 2018 Criminal Procedure Law (henceforth ‘CPL’), plea leniency was officially established as a foundational principle of the criminal justice system. One result of this codification is the skyrocketing use of plea leniency around the country, accounting for over 85 per cent of filed criminal cases as of 2020.Footnote 10

The official Chinese narrative of plea leniency is nothing but sanguine. Since its pilot implementation, plea leniency has been labelled as a practice that promptly and effectively punishes crime while strengthening safeguards for human rights. In the State's parlance, not only does plea leniency help to enhance judicial efficiency by strategically dispensing judicial resources across minor and serious criminal cases, it also ‘protect[s] procedural rights of defendants, respecting their principal position in criminal litigation and their freedom to choose the criminal procedure’.Footnote 11 In this article, I aim to challenge these premises. My thesis is that pursuing judicial efficiency and safeguarding individual rights are competing values which have yet to be reconciled in the Chinese plea leniency system. The operational dynamics of plea leniency is weighed heavily towards efficacy with little regard to the fundamental norms of due process and fairness in which the procedural legitimacy of this trial-avoiding initiative is grounded. Legitimacy, as Max Weber notes, is ‘the basis of every system of authority, and correspondingly of every kind of willingness to obey’.Footnote 12 While it is in essence ‘a belief by virtue of which persons exercising authority are lent prestige’,Footnote 13 it has proven to be the antecedent of the public's felt obligation to voluntarily defer.Footnote 14 Recent research has linked legitimacy to people's willingness to comply with legal authorities and their decisions through what Tom Tyler terms as ‘procedural justice’.Footnote 15 In this regard, people's subjective judgements about the legitimacy of authorities and the outcomes of procedures are predicated in great part on the fairness of the procedures through which legal apparatus exercise their authority.Footnote 16 Built on this immensely influential concept, my analysis teases out manifold mismatches between plea leniency and procedurally just decision-making in accordance with Tyler's model. In particular, I focus on the key elements of procedural justice as a conceptual lens to shed light on how plea leniency undercuts, rather than promotes, the fundamental rights of defendants. Taking into account the status quo of due process guarantees in the Chinese criminal justice system, my discussion concludes that the legitimacy of plea leniency, as perceived by defendants specifically and the public more generally, is fraught with peril, and as such, adopting this form of summary dispositions does more harm than good to an already illiberal criminal justice process.

To present this critical account, I rely primarily on the existing empirical research and the data collected from China Judgments Online. Created in 2013, China Judgments Online is a government-run database which offers a collection of judgments and decisions from every level of Chinese courts. It is generally assumed that Chinese criminal judgments reveal little, if any, useful information about the details of a case or the judge's reasoning behind the verdict.Footnote 17 Yet, as Benjamin Liebman demonstrates in his study of criminal justice in rural China by using criminal judgments from several courts in Henan Province,Footnote 18 there is merit in learning from publicly available cases. For one, the Government's mandate that every judicial decision must now be published in a comprehensive and timely manner brings forth the largest cohort of criminal judgments ever for public access in China.Footnote 19 Pursuant to the Online Publications Regulation released by the Supreme People's Court in 2016, judgments, rulings, notices, and other decisions that bring judicial proceedings to an end (except those dealing with state secrets, juvenile offenders, and politically sensitive matters) fall under the court's publication obligations.Footnote 20 Moreover, every criminal judgment uploaded online contains rudimentary yet adequate information for the purpose of descriptive and explanatory research. Typically, it includes content such as the types of crimes charged, the details of police evidence, the length of pre-trial detention, the roles of lawyers, the procedures of hearings, and the forms of sentences imposed (among others).Footnote 21 That being said, this study recognises the fact that data acquired from China Judgments Online are by no means always complete and intelligible. Factors such as changing rules on the publishable content, removal of materials due to local public availability policies, and judges’ preferences in judgment writing may all result in holes in the public record.Footnote 22 Bearing this in mind, my analysis also turned to the current scholarly research to complement and enhance the present study in the hopes of contriving a fuller and more empirically accurate delineation of the plea leniency system in China.

In this research, I scrutinised online criminal judgments from the courts in Shanghai in 2020 as a lens to explore the practice of plea leniency in this Eastern jurisdiction.Footnote 23 The reason for selecting Shanghai is twofold. First, Shanghai is one of the pioneering regions chosen to carry out plea leniency in 2016,Footnote 24 and by doing so, local legal authorities have over time amassed a breadth of on-the-ground experience of this particular program. It has been reported that the application rate of plea leniency in Shanghai in early 2019 already reached 58.4 per cent compared to 20.9 per cent at the national level.Footnote 25 Second, as one of China's most developed cities, Shanghai is known for its greater respect for law. This is largely demonstrated by the city's success in recruiting better-educated legal personnel and better-qualified officials as well as its efforts to curtail corruption and bureaucratic interferences in the legal system.Footnote 26 It is thus fair to submit that Shanghai is representative of the highest standards of law enforcement in today's China. For the purposes of this study, I collected a total number of 13,611 court judgments from the local basic-level and intermediate courts in Shanghai.Footnote 27 These judgments are derived from the mundane criminal cases applying plea leniency during the investigatory and prosecutorial phase and then finalised through summary court proceedings. This means that high-profile, politically sensitive cases that form part of the target of China's justice system are excluded, as they often end up being dealt with through quasi-criminal sanctions or even extra-legal mechanisms.Footnote 28 In addition, I precluded cases where defendants only pled guilty during the standard court procedure, not least because late guilty pleas before the trial judge do not tell us much about how plea leniency actually played out when defendants first made contact with the criminal justice system. Also, all selected judgments were from the cases of first instance. Appellate cases were removed because appeals in China are in most circumstances heard behind closed doors and based on paper reviews only.Footnote 29

This article proceeds as follows. First, I lay out the genealogical contours of plea leniency, with a review of the pertinent policy, law, and procedural reform in the Chinese criminal justice system. Then, I discuss the human rights ideal of plea leniency with reference to the four strands of procedural justice – voice, neutrality, respect, and trustworthiness. In interpreting plea leniency within the ambience of each particular element, I address the potential lacuna between principle and practice, and unravel where the discrepancy, if any, lies and how it impacts the perceived legitimacy of this new justice scheme. Lastly, I conclude with remarks about the essence of plea leniency and how it displays a converging trend with plea bargaining (in common law jurisdictions) towards a more managerial and administrative mode of criminal justice.

The Plea System in China: A Genealogical Review

For those navigating through the Chinese criminal justice system, ‘leniency to those who confess, severity to those who resist’ (Tanbai Congkuan, Kangju Congyan) is not an alien mantra. Endorsed as the Chinese ‘Golden Thread’ running through the criminal process,Footnote 30 Tanbai Congkuan, Kangju Congyan has cultivated a notorious yet prevalent culture of encouraging defendants to confess to a crime in exchange for sentencing concessions. This preponderant criminal justice policy was first recognised in the 1979 Criminal Law (henceforth, ‘1979 CL’) which stipulated that ‘anyone one who voluntarily surrenders herself to a judicial organ after committing a crime may be given a lighter (Congqing) or mitigated (Jianqing) punishment’.Footnote 31 In the 1979 CL, the scope of voluntary surrender was broadened to include ‘anyone under compulsory measures and serving sentences who truthfully confesses other crimes which are not known to a judicial organ’.Footnote 32 For scenarios falling outside the ambit of voluntary surrender, the CL was amended in 2011 to provide that ‘any truthful confession of a criminal suspect may warrant a lighter punishment, and a mitigated punishment if especially serious consequences are avoided as a result’.Footnote 33

Traditionally, the State's pursuit for confessions is believed to emerge from an inquisitorial culture of criminal justice wherein confession is perceived as a precursor to ‘objective truth’ legal authorities aspired towards.Footnote 34 Just like confessional evidence is central to the jury's verdict in the Western adversarial system (if the case proceeds to trial), the defendant's admission of guilt has a linear relationship with the criminal conviction in China's ‘truth-seeking’ system.Footnote 35 Obtaining confessions, as Ira Belkin remarks, has been viewed as the ‘king of the evidence’, which largely defines the police's approach to ‘solving’ crimes.Footnote 36 But the over-reliance on confessions has also developed an ethos of encouraging coerced guilty pleas through torture and other illegal means.Footnote 37 More recently, confessions have been conflated with an increasingly utilitarian concern about the growing resource scarcity in the Chinese criminal justice system. For over forty years since the country's marketisation, the ever-rising crime rates have morphed into an enormous drain on judicial resources.Footnote 38 Doubts are cast over judicial capacity in the context of mounting caseloads or, more accurately, the fact that adjudication resources have been more thinly spread across a large number of cases over time.Footnote 39 As such, the Chinese authorities are prodded into ruminating about a crucial question – can confessions reduce the process costs of reaching judgments?

The initial attempt to improve court efficiency was made in the 1997 Criminal Procedure Law (henceforth, ‘1997 CPL’) by introducing the simplified procedure (Jianyi Chengxu) within the jurisdiction of the basic-level People's Court. In contrast to the regular form of court procedure, this simplified procedure allows parties attending the trial to, inter alia, omit the statement on criminal facts, fasten the process of cross-examination, present crucial evidence only, and confine courtroom debate to key issues in dispute. Notably, legal conditions for the simplified procedure have varied over time; but it was not until the promulgation of the 2012 Amendment to the CPL that the defendant's guilty plea was established as the prerequisite for this summary court process.Footnote 40 Together with the conditions that ‘the facts of the case must be clear and supported by sufficient evidence’ and ‘the defendant has no objection to the simplified procedure’,Footnote 41 the guilty plea has been formally lain down as a justifiable ground for the expedition of court proceedings in China.

The application of the simplified procedure has gone into orbit following its induction.Footnote 42 While statistics are not misleading, reality shows that cases handled in the simplified procedure have yet to keep pace with the continuous upsurge of crimes prosecuted and then allocated to the judges’ dockets.Footnote 43 There are several possible reasons for this incongruity. In part, this is because of China having arguably gone down the path of over-criminalisation as a primary approach to the legions of social issues rapid national development has brought in its wake.Footnote 44 The number of people who end up getting caught in the criminal justice system has been on a steady overall ascendent trajectory during the past decades.Footnote 45 An equally salient factor, perhaps, lies in the country's recent introduction of the judge quota scheme (Yuan'e’zhi) which has put a further strain on judicial resources at the national level.Footnote 46 As part of decade-long judicial reforms, the judge quota scheme requires courts to re-calculate the ratio of judges to judicial assistants and administrative staff.Footnote 47 Fundamentally, this personnel re-arrangement is driven by the vision that the position of judge should be filled by those who are professionally trained and competent as opposed to court administrative staff who may be awarded a judge's title.Footnote 48 The upshot, obviously, is that by removing many ‘unqualified and incompetent judges’ from courts, the new judge quota rule has downwardly adjusted the proportion of judges in court staff composition across the country.Footnote 49

Against this backdrop, China has continued to pursue productivity through radical procedural reforms. In 2014, the People's Supreme Court and the People's Supreme Procuratorate enacted the Measure on Carrying out the Pilot Work of the Fast-track in Several Regions, which signalled the institution of a speedier procedure – the fast-track procedure (Sucai Chengxu). Intended to ‘optimise judicial resources and enhance quality and efficiency of handling cases’, the fast-track procedure takes one step further than the simplified procedure by skipping over the entire process of court inquiry and debate and only preserving the judge's announcement of verdict.Footnote 50 The commonalities between these two expedited procedures rest upon the trio of legal conditions – clear facts/sufficient evidence, guilty pleas and consent of defendants.Footnote 51 But what differentiates the simplified procedure from the fast-track procedure is their applicable scope – while the former applies in principle to all types of criminal offences, the latter usually targets cases in which the perpetration is punishable by no more than three years imprisonment.Footnote 52

Evidently, the construction of the simplified and fast-track procedures has – to a marked extent – paved the way for a localised plea-based justice system to thrive. It almost comes as no surprise when China promptly inaugurated the model of ‘Admission of Guilt and Acceptance of Punishment (Plea Leniency)’ in 2016 as a holistic approach to plea settlement and its procedural parameters. Pursuant to the Decision on Carrying out Pilot Projects in Some Cities on the System of Plea Leniency for Those Who Admit Guilt and Accept Punishment in Criminal Cases (henceforth ‘Plea Leniency Pilot Project Decision’), this new initiative was first introduced as a experimental program in 18 developed cities.Footnote 53 Advanced by the 2018 CPL for nationwide expansion, plea leniency was then structured to amalgamate the simplified and fast-track procedures, thereby formulating an arguably all-encompassing approach to guilty pleas in the Chinese criminal justice system. More remarkably, if the previous abridged procedures were aimed at curtailing the process of fact-finding in preserving the judge's power to mete out appropriate sentences, plea leniency entails not only the defendant's acknowledgement of guilt, but also the defendant's consent to the procuratorates’ recommended sentencing range, type of punishment, or even means of implementation to alleviate the judge's duty of sentencing.Footnote 54

In the discursive context surrounding plea leniency, the need for greater efficiency has verily catalysed the relentless trend to resolve criminal cases more quickly and economically. Indeed, one study used data on driving under influence cases in a pilot city in Fujian to indicate that the overall depositional time was reasonably shortened by putting plea leniency in place.Footnote 55 New measures of setting up time limits for guilty pleas and encouraging the accused to enter a plea agreement before trial were identified as propellants for the acceleration in processing a great deal of criminal charges.Footnote 56 But the perceived effort to match caseloads to court capacity by fastening the process of conviction, from the State's perspective, has yet to amply characterise this new guilty plea model. In particular, the Guiding Opinions on the Application of the Plea Leniency System (henceforth ‘Guiding Opinions’) passed in 2019 lucidly proclaimed that plea leniency is an instrument to promote the rights of defendants. In addition to ‘better allocating judicial resources and improving efficiency of criminal litigation’, plea leniency is thought to yield significant effects on ‘timely and effectively punishing crime and strengthening human rights protection’.Footnote 57 Put differently, plea leniency is set to play a binary role by pursuing judicial efficiency whilst robustly safeguarding individual rights during relevant criminal proceedings. In view of these grand missions, Zhang Jun – the chief procurator of the People's Supreme Procuratorates – has hailed the plea leniency system as a ‘Chinese Approach’ to ‘enriching crime control conducive to the socialist criminal justice system with Chinese characteristics’.Footnote 58

In the remainder of this article, I will delve into the patterns and characteristics of this ‘Chinese approach’, to inspect whether and to what extent the everyday operation of plea leniency corresponds to the stated goal of endorsing individual rights. In other words, if plea leniency is designed for a more cost-effective purpose, how does this mesh with human rights protection that requires due process considerations and basic principles of fairness? This question is particularly significant given China's intention to reinforce guilty pleas as the centrality of criminal justice administration. In addressing this question, I draw on the concept of ‘procedural justice’ advanced by Tom Tyler and his collaborators to engage in a discussion about plea leniency's true nature and inherent value. My attempt here is not to repeat the scholarly effort to translate Tyler's procedural justice ideal into the operational context of the plea-led programs.Footnote 59 Rather, I hope to focus on the core ingredients of procedural justice as a prism to investigate whether plea leniency has fulfilled or derailed from its advertised rationale of being a rights-safeguarding practice. As we will see, although procedural justice research has predominately concentrated on police-citizen interactions, the procedural justice dynamic is at work in many other organisational settings. By extension, it applies to plea leniency because of the way legal authorities develop, present and respond to plea agreements, and the interface with defendants which, in reality, represent nothing more but a unilateral decision-making process of the State.

Making Sense of Plea Leniency: Legitimacy, Procedural Justice and The Goal to Promote Individual Rights

In his seminal book Why People Obey the Law, Tom Tyler presented the then-inspiring findings that people comply with legal authorities and their decisions not because they fear punishment but because they regard legal authorities and the law they use as legitimate.Footnote 60 Going further, his studies have showed that views about legitimacy have causal links to perceptions about the fairness of the decision-making process adopted by legal authorities.Footnote 61 To boost procedural fairness, as Tyler posits, is to strengthen the experiences of people with legal authorities through four channels: (1) voice – allowing people to tell their side of story before decisions are made; (2) neutrality – decisions are made in an unbiased, rule-based, and consistent fashion; (3) respect – treating people with dignity and courtesy; and (4) trustworthiness – having the best interests of people at the heart of the decision-making process.Footnote 62

Empirical evidence that supports the procedural justice model is ubiquitous.Footnote 63 Within the field of criminal justice, the research on the psychology of procedural justice has illustrated, quite emphatically, that in policing, trials, and sentencing, procedural justice has a significant impact on how people evaluate their outcomes. It was revealed that procedural justice in the processing of defendants’ cases drives outcome satisfaction and promotes cooperation with legal authorities and deference to their directives – which together, all constitute manifestations of high degrees of legitimacy.Footnote 64 Of particular importance is the finding that procedural justice works not only in environments where there are established procedural and substantive rules with a third-party neutral, but also in mediation, negotiation, and other less formal settings which are less rule-based and judicially regulated.Footnote 65 Several studies touching on legal dispute settlements have demonstrated that the effects of procedural justice are stronger predictors of the acceptance of the outcomes than those of distributive justice.Footnote 66 Along this line of thought, the work of Michael O'Hear suggests that procedural justice can be transplanted into office policy and practice of plea bargaining.Footnote 67 The American criminal lawyer sees procedural justice as providing strong support for the legitimacy of the defendant's acceptance of plea decisions in an increasingly flexible and discretionary criminal justice system.Footnote 68

Such contention is echoed by Tyler and others whose research further stresses the salience of procedural justice in legal negotiations. In particular, it is argued that procedural justice helps bridge the inherent gap between non-judicial dispute resolution (eg, plea bargaining) and the formalist rule of law which comports with formal and judicially-based resolution of conflict.Footnote 69 For a long period of time, critiques of the privatisation and informalisation of dispute resolution have revolved around concerns over this trial-avoiding scheme being individualistic, prejudicial, and lacking public accountability. Therefore, for informal dispute resolution to operate as general, certain, non-retroactive, and free of state discretionary power, its adherence with procedural justice is important because ‘people's everyday understanding of what procedural justice means conforms to many of the key elements that define the rule of law’.Footnote 70 According to Tyler, the doctrines of the rule of law and procedural justice are largely identical – they both strive to provide legitimacy to legal authorities and the procedures in question. The rule of law applies fixed laws in an equal and neutral way while respecting individual rights. In the same vein, procedural justice advocates neutral and trustworthy decision-making, allowing people a voice, and treating them with politeness and respect. From this point of view, ‘the rule of law and psychological perceptions of fairness (procedural justice) may share an inextricable, symbiotic relationship’ because they are both rights-driven and equality-heuristic.Footnote 71

Then, how does the philosophy of procedural justice help us to understand plea leniency in China? Being trumpeted as an instrument that enhances individual rights, the legitimacy of plea leniency hinges greatly on whether this new depositional measure can produce procedurally just outcomes and meet perceptions of fairness as per the rule of law. In what follows, I will conduct this inquiry within the context of Tyler's model of procedural justice featuring the four famous pillars: voice, neutrality, respect, and trustworthiness. The first two factors concern how legal authorities make decisions. The last two factors pertain to how legal authorities treat people in the decision-making process. Let us consider each in turn.

Voice – Can Defendants have their Side of Story Presented?

The procedural justice theory propositions that providing opportunities for voice is closely linked to perceived fairness of the outcome. If the defendant is allowed to state her perspective or tell her side of story before the decision is made, she is more likely to see the decision as fairly and legitimately made.Footnote 72 Two common methods, as O'Hear opines, may help the defendant present her side of story in a plea-led scenario.Footnote 73 First, police ought to be diligent about collecting the defendant's story in their reports.Footnote 74 Second, defence counsel is expected to convey the defendant's story before the prosecution makes a plea offer.Footnote 75 In the Chinese system of plea leniency, however, both measures are nearly unattainable not least because neither police nor counsel are interested or feel obligated to speak to and for defendants. In a nutshell, the preoccupation with confessions in China's ‘truth-seeking’ criminal process has over time made the police a coercive institution,Footnote 76 which likely becomes haughtier in the plea leniency process when under pressure to obtain early guilty pleas. At the same time, the difficulty of Chinese defence lawyers in providing effective legal assistance has hitherto remained a lingering issue that plagues the Chinese criminal justice system.Footnote 77 The generally poor quality of legal representation is unlikely to be reversed by the introduction of plea leniency which is devised to downplay the confrontational features of the justice process. Conceived in this way, plea leniency narrows the venue for defendants to have their voice heard by diminishing their already weak rights in speedy criminal proceedings.

The indifference of police to learn the defendant's side of the story is hardly surprising. For decades, policing in China has been dominated by the authorities’ obsession with social control, serving the prevailing socio-political goal of the preservation of stability.Footnote 78 This underlying ethos of police power harks back to the Maoist era where a class-dichotomised society presaged the need for ‘political justice’ through heavy-handed policing of ‘class enemies’.Footnote 79 With China transforming itself from an egalitarian society under Mao to a stratified society following economic liberalisation, the State has witnessed an unprecedented spike in crime wrought by a constellation of new social problems.Footnote 80 As such, concerns over deteriorating public order have propelled the police towards a more demanding social control function by extending their position at the forefront of the fight against crime.Footnote 81 This is done, as Mike McConville points out, through the making of overly punitive and oppressive laws which operate as ‘a major resource providing legal cover for [police] actions’.Footnote 82 In any event, policing in China has shaped a culture of presumption of guilt.Footnote 83 Reflecting on what Herbert Packer termed ‘the crime control model’,Footnote 84 it is widely acknowledged that Chinese police prioritise the efficient suppression of criminality in the interests of social order by means of almost exclusive investment in gathering inculpatory evidence.Footnote 85 Instead of respecting the defendant's right to the presumption of innocence as notionally incorporated in the CPL,Footnote 86 police investigation is characterised by an approach to securing convictions on the basis of ‘substantive truth’.Footnote 87 Yet, this search for truth is not performed on grounds of objective evidence, but ‘constructed’ by police to align with the pre-determined guilt of the defendant.Footnote 88

Yu Mou, for example, ascribes this ‘construction of guilt’ to the reality that the ‘story-telling’ of criminal facts was monopolised by police.Footnote 89 In her observational fieldwork of the Chinese criminal justice system, it found that effort to establish the factual guilt of the accused is intricately interwoven with the misuse of power by police who coerce, induce, and unduly influence the accused to confess to a crime.Footnote 90 Where a confession does not conform to the ‘official version of truth’, police were not hesitant to distort, manipulate, and even fabricate the confession to meet the evidential threshold for prosecution.Footnote 91 Largely, such malpractices were fuelled by a set of feeble procedural rules loosely protecting the defendant's right to remain silent and privilege against self-incrimination, as typically valued in most common law jurisdictions.Footnote 92 As disclosed in Mou's research, the abuse of police power was pervasive in standard criminal procedure. Considering this, it may be sensible to assume that police wrongdoings can only be more acute in the simplified and fast-track procedures, given that cases applying plea leniency in these procedures necessitate a more rapid and streamlined process of case deposition. An avid pursuit of confessions or guilty pleas tends to give rise to increased magnitude of coercive or deceptive police practices, as manifested in Western plea bargaining scholarship.Footnote 93 On this point, scholars are pessimistic about any serious commitment to the defendant's voice through police reports in the context of plea negotiations.Footnote 94 Similarly, it is reasonable to be doubtful of Chinese police being sensitive to the defendant's story, as almost every legal right in police investigation is either vaguely prescribed or treated as a bargaining chip to be traded for leniency at the sentencing stage.Footnote 95

My data on court judgments from twenty courts in Shanghai vindicates this proposition. Across 13,611 criminal judgments on plea leniency cases, it is found that police more often than not overlook, intentionally or inadvertently, the defendant's side of story in their performance of their investigative duties. Figure 1 sets forth the numbers of cases where police included the defendants’ version of facts (Biancheng) in their case dossiers delivered to the prosecution and presented at summary trials. Among 9,543 cases finalised through the simplified procedure where the defendants were sentenced to terms of three years or more, the defendant's arguments appeared only in 113 court judgments. Moreover, there was a significant decline in police attention to what the defendant had to say among less serious cases. Among 4,068 cases heard through the fast-track procedure where a sentence of three years imprisonment or less was usually given, the mention of the defendants’ arguments was only found in 14 cases. Of course, it is likely that in some court reports judges omitted to incorporate the defendants’ argument given that all defendants had admitted they were guilty before the trials commenced. It could also be possible that police failed to record it in their report at the outset. Yet, such a disproportionately high number of judgments where the defendant's voice was missing elucidates, at a minimum, the low interest of police in grasping perspectives different to the official perception of ‘truth’, provided defendants were ever given the chance to speak up in the first place.

Figure 1. The Numbers of Cases Presented with/without the Defendants’ Arguments

If police are apathetic about the defendant's point of view in general, can legal counsel instead play a more useful role in raising defendant voices? Notably, China has made the right to legal representation a focal point in recent legal reforms. In October 2017, the Supreme People's Court and the Ministry of Justice jointly issued the Measures for Carrying out the Pilot Work in Full Coverage of Lawyers’ Defence in Criminal Cases (henceforth, ‘The SPC-MoJ Measures’). In eight provinces and municipalities,Footnote 96 it is mandated that every accused should either be assigned a professional defence lawyer or offered counsel assistance from legal aid services.Footnote 97 Drawing on the ‘successful experience’ amassed in the test regions, in January 2019 China pronounced the expansion of this practice across the country.Footnote 98 This move aims to ensure that counsel appear in every State case, particularly those involving plea leniency where summary trials are meant to take place. Practically, the power to grant legal aid is vested in provincial, municipal or local legal aid centres upon request by the defendant who meet the eligibility criteria.Footnote 99 Once assigned to a criminal case, the duty and legal aid lawyer is salaried by local justice bureaus to offer free legal services, including but not limited to counselling and legal representation at trial.Footnote 100

To be sure, there is a strong rationale behind the national push for this full-coverage legal representation. Since the modernisation of the legal system in the late 1970s, China's inquisitorial criminal justice system has been repetitively accused of lacking adequate protection for defendants to withstand the intrusive force of the State.Footnote 101 On the one hand, the overall rate of legal representation in criminal cases has at all times been below 30 per cent, with affluent locals being relatively more lawyer-equipped than impoverished locals.Footnote 102 On the other hand, efforts by defence counsel to provide adequate legal assistance have been impeded by the institutional dynamics of Chinese criminal proceedings that inhibit lawyers from acting as an adversarial advocate.Footnote 103 The paramount objective of social control has created an overpowering legal apparatus. Relatedly, obtaining confessions at all costs and thus, positing it as the centre of gravity within the exercise of the state power has reduced the role of counsel to symbolic significance. Indeed, numerous studies have empirically proved that Chinese counsel are riddled with various predicaments in their everyday defence work.Footnote 104 The problems run the gamut from difficulty accessing case files and suspects in detention to the difficulty in collecting evidence for defendants.Footnote 105 Apart from constituting an action against the best interests of their clients, challenges in hearings against State authorities can also lead to defence lawyers being brandished as ‘foes’ of the State and incurring criminal liability under the CL.Footnote 106 It comes as little wonder, then, that this has led many commentators to assert that the right to legal representation, though being enshrined as a constitutional norm, has largely remained a construct on paper.Footnote 107

In many respects, legal counsel walk a thin line in China's criminal process. It is of course undeniable that outspoken lawyers do exist and are devoted to fight for defendants’ rights. Sida Liu and Terence Halliday's work on criminal defence in China identified this group of lawyers as ‘political activists’ and ‘progressive elites’ who uphold and advocated for liberal values in the system while representing their clients.Footnote 108 But their research also pointed towards even larger legions of ‘pragmatic brokers’ and ‘routine practitioners’ who were usually powerless to challenge the embedded legal culture of criminal justice being disparaging towards defence lawyers.Footnote 109 This then begs a more pertinent question of whether and to what degree lawyers are willing to convey a defendant's voice in plea leniency. The initiatives of full-scale legal representation are certainly laudable, but evidence showed that the superficial counsel appearance can neither guarantee sufficient legal assistance nor present meaningful voice opportunities to inform plea decisions.Footnote 110 It might be an over-statement to say that counsel play no role at all in plea leniency. However, it seems to be clear that the defendant's right to legal representation is at greater peril during the simplified and fast-track procedures than during the full-scale procedure. For example, one recent study conducted to examine the width and depth of legal representation in plea leniency showed a fairly negligible role of counsel in China's summary criminal proceedings.Footnote 111 Based on a questionnaire survey among defence counsel (n = 374) and prosecutors (n = 375) in one selected pilot city (City H in Z Province as anonymised by the researcher), the findings indicated that counsel (including privately retained lawyers and duty lawyers) had found themselves embroiled in the plight of only being able to help defendants with the interpretation of law while ironically, encouraging and witnessing defendants’ acceptance of plea agreements.Footnote 112 A particular discovery of this research illustrated the gulf between the perceived function and the actual role of counsel in representing their clients in plea leniency cases.Footnote 113 While the majority of interviewed lawyers agreed that defence counsel ought to ‘comprehensively act in their clients’ best interests’, about 89 per cent of respondents conceded that their role was, on the practical front, limited to only seeking lenient sentencing outcomes.Footnote 114

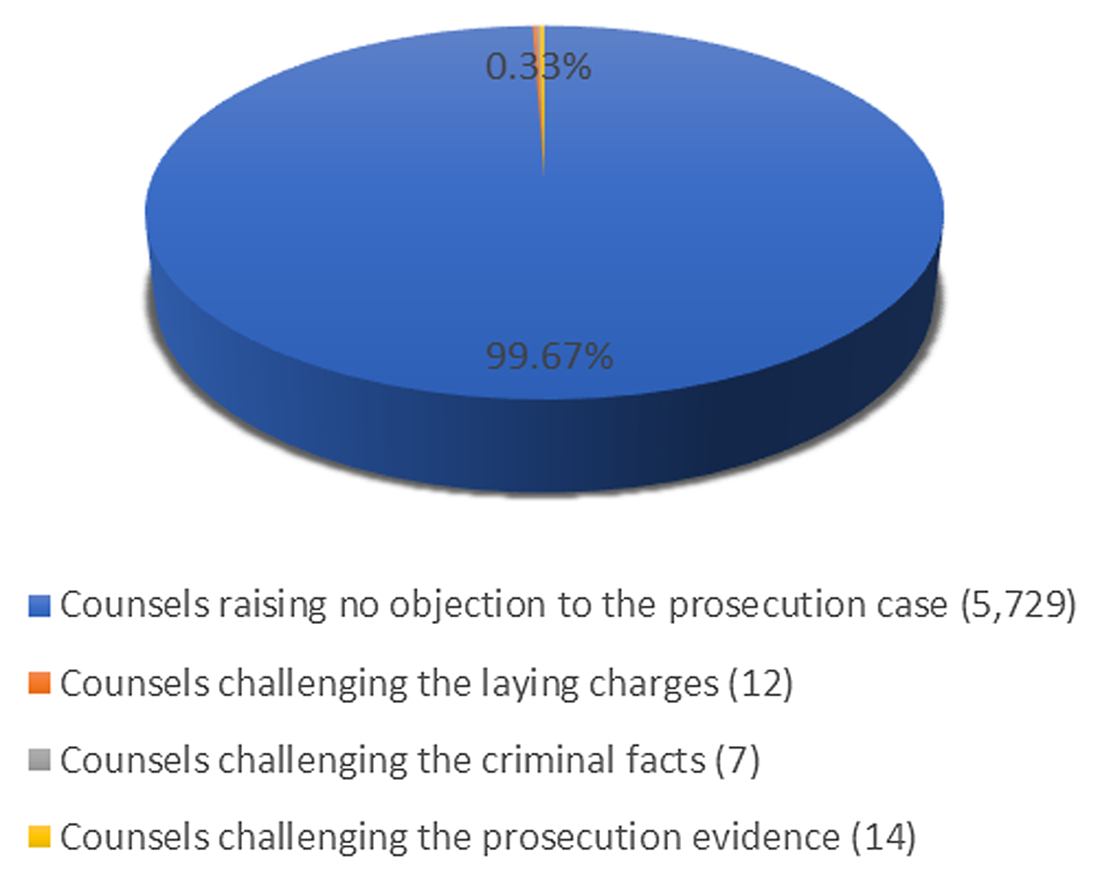

My analysis of the court judgments from Shanghai attests to this observation. Out of the dataset, I compiled a list of 5,748 cases in which defendants were legally represented during the summary trials. The absence of counsel appearance in almost two-thirds of trials is not really startling – for cases to be proceeded by way of simplified and fast-track court proceedings, most defendants must have pled guilty at the investigatory or prosecutorial stage where counsel appearance was mandatory. This has made counsel appearance at trial optional rather than necessary. However, what appears to be striking is the ineffectiveness of counsel attending the trial to operate as the guarantor of defendant voice in any impactful way. The Guiding Opinions explicitly designates the summary trial process as essential for assessing legality, truthfulness, and voluntariness of the defendant's guilty plea.Footnote 115 Consistent with prior findings, nevertheless, it found that counsel were almost always reluctant to question the official narrative of criminal facts and prosecutorial evidence in relation to the defendant's guilt. More frequently, counsel focused their defence predominately on reinstating the defendant's early guilty pleas and leveraging it to seek sentencing concessions. Figure 2 provides an overview of cases in which counsel either raised no objection to or disputed the prosecution's case. It indicates that in almost every case the counsel opted not to contest the validity of guilty pleas presented by the prosecution (5,734). Only 19 cases’ counsel opposed accepting the laid-down charges, the criminal facts, or the prosecution evidence.

Figure 2. The Percentage of Counsels Raising No Objection to / Challenging the Prosecution's Case

The reasons that counsel showed no genuine intention to confront the prosecution may in part be due to the fact that counsel spotted no loopholes in the State cases, since most plea leniency matters typically involve relatively minor offences with simple facts and clear evidence.Footnote 116 It was more likely, though, that the undesirable standing of counsel in the criminal justice system refrained them from challenging the ‘authority’ of law enforcement agencies. As counsel have long been marginalised or even oppressed in the system, to challenge the prosecution case, especially after defendants have allegedly admitted guilty, is to ‘touch the tiger's buttocks’ that may backfire on argumentative or aggressive counsel.Footnote 117 More pragmatically, avoiding hostility seems to be a realistic strategy, particularly for those representing defendants for the first time at summary trials, thereby affording them with very little knowledge about how and why their clients entered a guilty plea in the first place. Under these circumstances, it is not uncommon that counsel only grasp at a sense of self-worth through arguments for lenient sentences. In all 5,748 cases, counsel put forth discounted punishment on the basis that defendants had pled guilty at the stage of investigation or prosecution. Instead of raising this as a new claim, counsel's request for leniency in sentencing served as a reminder to procuratorates to keep their early promises on lighter punishment as part of the plea deal. In addition, just like what Liebman revealed in his study of criminal judgments from Henan,Footnote 118 the fact that the defendant had actively paid compensation or restitution was relied heavily upon by counsel to convince the judge a lenient sentence should be granted. Figure 3 illustrates a variety of reasons commonly argued by counsel to request light penalties. Other than confessions and compensation, the other factors to which counsel endeavoured to draw to the judge's heed include the defendant being a first-time/occasional offender and the victim's forgiveness towards the defendant. Typically, these reasons were presented in tandem in the hopes of carrying greater persuasive weight before the sentencing judge.

Figure 3. The Reasons Argued by Counsel for Lenient Sentences

Of course, counsel's focus on sentencing concessions should not be taken by surprise given China's prevailing culture of over-relying on the prosecution's view of the facts to determine the truth during criminal trials.Footnote 119 This means that the most feasible time for counsel to alter authorities’ narrative lies in the prosecutorial stage where the case is yet to be finalised through guilty pleas and filed for court hearing. On a side note, judicial favouritism towards the prosecutorial evidence which are mainly comprised of case dossiers and written statements has invoked emerging concerns about the fairness of trial. To reverse the pivot of the criminal process, the Government initiated a ‘trial-centeredness’ campaign in 2014 to promote the long-absent elements of adversarialism characterised by live witnesses, cross-examination, and court debate.Footnote 120 It is argued that the ideal of trial-centeredness should also run through the process of plea leniency,Footnote 121 mandating the judge to gauge an overall apprehension of the guilty plea as to its legality and voluntariness. The above data, however, tell a different story. While the data exhibited the limited role of counsel in offering alternate accounts for judges to acquire a full picture of events in court proceedings, a general pattern of lawyering in plea leniency surfaces. Counsel were not accorded greater power to act more freely and assertively as the defendant's agent when facing legal authorities in plea leniency schemes. With the criminal process being compressed to settle criminal matters in a time-saving manner, counsel carry a less adversarial function as a result. Thus, a common thread through the findings of the present research and several studies alike is that counsel appearance, while being promoted as a precondition to an informed guilty plea, amounted to a mere procedural formality as opposed to a genuine form of procedural protection.Footnote 122

Neutrality – Can Defendants Access Consistent and Principled Decisions?

In addition to voice, the perceived fairness of a procedure depends on decision-making being neutral, consistent, rule-based, and without partiality.Footnote 123 This entailed authorities being upfront and explaining to defendants the reasoning behind their decisions in a transparent manner. To this end, Tyler and others have identified objective criteria in place of personal views as an important means by which a decisionmaker can establish her neutrality.Footnote 124 Within the plea-bargaining context for example, explanations need to be predominately conveyed by prosecutors – though counsel may take on a similar role – to help defendants enter into an informed plea.Footnote 125 Following explanations, authorities were supposed to equally and consistently apply rules across people in like situations.

Plea leniency in China has, unfortunately, failed in both aspects. As a requirement, the plea leniency ordinances – including the 2016 Plea Leniency Pilot Project Decision, the 2018 CPL and the 2019 Guiding Opinions – have all demanded the explication of the nature and procedure of plea leniency by police and procuratorates before they make any plea offers.Footnote 126 Primarily, this statutory requirement involved an unequivocal explanation of the defendants’ procedural rights and their ‘free choice’ to confess and receive lenient sentences accordingly.Footnote 127 In official terms, advising the defendant of their right to select court proceedings (that is, the summary procedure or the ordinary procedure) formed an integral part of plea leniency because it lay in close association with voluntariness of guilty pleas.Footnote 128 Conceptually and operationally, voluntariness bolstered the legitimacy of plea-based criminal justice, as evinced in the common law jurisprudence of plea bargaining (especially in the US).Footnote 129 Not only was it a key determinant of legally binding guilty pleas, but plea voluntariness was a critical prerequisite to the circumvention of court hearings, and a waiver of a spate of fundamental rights conferred on the accused.

Oftentimes though, plea voluntariness is coalesced with the right to legal representation and the quality of legal assistance. Despite the argument that the choice situation imposed by plea bargaining on the accused is ‘intrinsically coercive’,Footnote 130 it is assumed that effective counsel assistance at the critical pre-trial stages of prosecution may somewhat sustain the volitional power of defendants.Footnote 131 However, the over-dependence on counsel's diligent work overlooks the duty of explanation that legal authorities ought to discharge in parallel. More likely than not, a guilty plea will not be ‘knowing, intelligent and voluntary’ if legal authorities do not energetically engage in providing information and expounding on reasoning – which together, act as evidence of even-handedness and objectivity in the bargaining context.Footnote 132

Suffice to say, the idea of legal apparatus being open, transparent, and communicative is particularly important in China's plea leniency programs. As discussed earlier, defence counsel in China were overly incompetent. It inevitably places obligations on legal authorities to guarantee defendants' voluntariness of plea; no innocent person should be forced or induced to admit guilt. Empirical studies, however, have illustrated results contrary to such commitment. Based on his examination of plea voluntariness in two districts of City A and B, Xin Zhou suggested that in two respects, police and procuratorates had largely left defendants in the cold when presenting plea agreements and accordingly, making plea decisions.Footnote 133 First, there was significant variation in timeframes for informing defendants of their right to plead guilty. In both districts, police were found to timely advise defendants of their relevant entitlements upon the first questioning, as stipulated in the CPL.Footnote 134 However, after the case was transferred from police to procuratorates for formal prosecution, the prosecuting agency in City A did not commence plea leniency conversations at the earliest opportunity until the indictment was presented to the trial court – that is, almost at the end of the prosecutorial period.Footnote 135 Contrarily, its counterpart in City B initiated plea leniency conversations normally within three days of receiving the case dossiers from the police.Footnote 136 Regardless, the findings revealed that legal authorities in both regions enjoyed exclusive discretion to opt for a time to initiate the plea leniency process as they thought fit when meeting with defendants.

Second, with regards to the content of authority-defendant communications, Zhou's research unveils a common practice of State authorities. That is, police and procuratorates tended to confine their interactions with defendants to providing information about the procedural rules and legal conditions of plea leniency.Footnote 137 At the same time, they were reluctant to disclose more particulars of the case in question.Footnote 138 Interestingly, many interviewees in this study happened to see the delivery of the ‘plea leniency agreement’ (Renzui Renfa Jujieshu) as an alternative to their duty of explanation.Footnote 139 Equivalent to a standard form contract in substance, the plea leniency agreement was said to contain all the necessary details that defendants were required to read through. Procedurally speaking, signing off on this agreement meant that defendants were agreeable to the laying charges and proposed punishments as a package deal offered by procuratorates. Still, this paper-based informing model does not fit well with what Tyler deems ‘openness and objectivity’ of neutrality, simply because defendants were not given genuine conversational opportunity to attain an all-round vision of their cases which was imperative to a knowing and intelligent guilty plea. This was exacerbated by the absence or difficulty of counsel to attain the criminal facts in sufficient detail on the defendant's behalf. Realistically, to the best of the defendant's belief, admitting guilt and accepting a discounted sentence turned out to be a rational choice insofar as little was known about the strength of the prosecution case. Here, defendants were faced with a paradoxical situation – their right to access evidence (whether that be for or against them) was impaired under the plea leniency process, which would otherwise be better protected in some form of judicial oversight should their cases proceed via standard procedure. In this light, the lack of a neutral process in presenting plea deals occasioned a risk of defendants involuntarily entering in guilty pleas, rendering plea-based convictions unsafe or unsatisfactory and open to appeals.

The foregoing analysis only tackled one aspect of neutrality with reference to plea leniency practices. On a further practical note, procedural justice ideas of neutrality only addressed the requirement that decisions of legal authorities be made through the consistent application of rules and consideration of facts.Footnote 140 When transplanted into plea arrangements, they denoted that plea decision-making should conform to established standard criteria; and legal agencies need to minimise discrepancy by ‘treating like cases alike’. These norms, however, do not seem to be respected nor were they upheld in China's simplified and fast-track procedures. Across the spectrum of plea leniency practice, divergence was perceptible across different cases and defendants.

One exemplar of this incongruency appertains to the selective application of plea leniency for different types of crime. Unlike plea bargaining in Anglo-American countries where plea deals are almost equally struck across misdemeanor and felony cases,Footnote 141 plea leniency in China has been susceptible to discretionary application. Specifically, this programme had devoted its resources disproportionately to minor offences in contrast to more serious offences. In 13,611 court reports, it is found that three broader categories – crime endangering public security, crime infringing property rights, and crime impeding social order management – have topped the list of plea leniency cases in Shanghai. When it comes to individual offences, the charges of theft, dangerous driving, picking quarrels and provoking trouble stood out in each category. Figure 4 and Figure 5 represent the ten most common criminal offences processed under plea leniency in Shanghai. The data showed that the crimes dealt with by the simplified procedure and the fast-track procedure are mostly overlapping despite the fact that these two procedures were created with their own respective targets.

Figure 4. Ten Most Common Criminal Offences Processed through the Simplified Procedure

Figure 5. Ten Most Common Criminal Offences Processed through the Fast-track Procedure

Here, the data provides a window into the routine practice of plea leniency that is both over- and under-inclusive. On the one hand, these commonly recorded perpetrations almost all fall within a general category of minor offences. On the other hand, serious crimes such as violent and sexual offending were generally left out. This is reflected in statistics which indicated that over the last year, Shanghai courts only adjudicated 27 robbery cases, 10 arson cases and 5 murder cases (out of 9,543 cases) through the simplified procedure. In the fast-track trials, the gravest offence heard was rape (n = 1) (out of 4,068 cases). This is not to deny that written judgments may not have yielded the full picture of practical divergences. For example, picking quarrels and provoking trouble as a ‘pocket crime’ embraced a great mass of offences, ranging from willfully attacking persons with serious circumstances to creating a disturbance in a public place that caused serious disorder.Footnote 142 This surely necessitated further on-the-ground observations to explore variations in documented crimes across different plea leniency processes. Regardless, the dominant focus of plea leniency on minor offences was statistically conspicuous, as manifested not only in the public records collected for this study but also scholarly findings in the same line of research.Footnote 143

Indeed, the under-representation of serious crimes in plea leniency resonates with policy considerations. The Guiding Opinions, for example, sanctioned a binary model by impelling legal authorities to dispose of minor criminal cases as simply, quickly, and leniently as possible.Footnote 144 The dominant tenor was that plea leniency should be applicable especially to ‘first-time offenders, casual offenders, crimes of negligence, or juvenile crimes where the social harm is not great’.Footnote 145 By contrast, police and procuratorates should cautiously apply plea leniency in cases of crimes that ‘seriously endanger national security or public safety, serious violent crimes, as well as major and sensitive that have drawn broad public concern’.Footnote 146 Even so, leniency ought to be entertained prudently in serious and/or high-profile cases, avoiding the risk of ‘going against the public's sense of fairness and justice’.Footnote 147 Certainly, there was nothing wrong with nuanced administration of criminal justice in light of special circumstances of individual cases. The deliberate preclusion of serious offences, however, indicated a pronounced departure from a neutral process that is rooted in impartiality and uniformity. Depriving the right of certain groups of defendants to enter in a plea leniency deal was a parity violation, as if guilty pleas of serious offenders carry less weight than those of minor offenders. A more troubling issue perhaps was the dearth of a national yardstick to guide the classification of minor and serious cases around their intricacies. In many localities, authorities were driven to adopt standards tailored to local conditions;Footnote 148 but what is regarded as a serious crime, eg, the national security offence, can be interpreted in divergent ways across Beijing, Guangzhou and Xinjiang. As such, the existence of regional variations in plea leniency was a far cry from the principled criteria of practice which underpinned the procedural justice ideal of neutrality.

But even with crimes managed by means of plea leniency, cases were hardly treated alike. Mainly, defendants who go through plea leniency have experienced sentencing reductions unevenly applied across time and region. In an extensive quantitative study of sentencing outcomes regarding the particular crime of dangerous (drunk) driving, the researcher found that the scale, extent and mode of leniency granted on penalties varied enormously over time and from area to area. In some locations (Beijing, Shanghai, and Qingdao) judges were more inclined to reduce the length of imprisonment as a concession for guilty pleas.Footnote 149 In others (Fuzhou and Xiamen), however, judges were more inclined to impose probation in place of short-term incarceration for most minor offences.Footnote 150 Still, certain regions (Hangzhou) witnessed a static pattern of sentencing despite the traction of plea leniency gained in the local criminal process.Footnote 151 Across China, the degree to which sentence mitigation was effectuated on the ground was particularly telling to the absence of parity in the plea leniency process. This research showed that while some cities experienced a high level of leniency by more than 60 per cent (eg, the amount of reduction in sentence length), others only awarded less than 5 per cent leniency as consideration for guilty pleas.Footnote 152

Respect – Are Defendants Treated with more Dignity?

At the operational level, voice and neutrality are connected with a more technical aspect of decision-making. In the procedural justice model, however, the quality of interpersonal treatment in the decision-making process mattered as much as how the decision was made. It has been established that legitimacy and perceived fairness of a procedure also developed out of the provision of respectful treatment of people, including having their rights acknowledged and their needs considered.Footnote 153 As such, legal authorities in a plea-seeking context may undertake a series of measures to advance perceptions of respect. For example, they should treat defendants with dignity by discouraging harsh treatment such as prolonged detention, physical coercion, and various other forms of excessive force.Footnote 154 While dignity has various meanings and functions depending on the explanatory context, it pertained generally to the basic rights of a person to be valued and respected for their own sake, and to be treated justly and decently. To this end, it is then imperative to provide defendants with a threat-free environment in order to avoid the extraction of involuntary guilty pleas through coercive and forcible measures. Concomitantly, legal authorities should cling to the presumption of innocence until a guilty plea was voluntarily entered. This means that the correlated rights of defendants need to be upheld, especially those central to the protection of defendants from unwarranted incursions on their liberties by the State.

At any rate, there was little evidence that plea leniency operates under the aegis of refraining from repressive practices. Over the past decades, China's image as a punitive or ‘carceral’ state has been largely tied with its stunningly yet steadily high rate of incarceration and conviction. Unlike the adversarial system where bail is a prime facie right of the suspect, pre-arrest detention (Juliu) and arrest (Daibu) have long been the norm in the Chinese pre-trial process.Footnote 155 Substantial empirical research showed that the rate of arrest approval nationwide has never fallen below 80 per cent despite different natures of suspected offences.Footnote 156 Based on court judgments in one of the Chinese cities during 2012–2013, Moulin Xiong's study illuminated that on average the length of incarceration pending trial is 174.8 days.Footnote 157 While lengthy custody applied generally to serious offences including intentional assault, drug trafficking, and robbery, minor offences such as property perpetrations attracted an analogous amount of confinement.Footnote 158 Just like pre-trial detention, the conviction rate in China was consistently and persistently high. Nearly 100 per cent conviction rates at any given time have intensified the aspiration of the Chinese criminal justice system towards purported ‘substantive justice’ at the expense of due process and individual rights.Footnote 159 What was equally striking was the high use of imprisonment following convictions. Over time, China has been arguably secondary to the US in terms of its prison population, despite the accurate number of incarcerated people remaining a national secret yet to be disclosed to the public.Footnote 160

The State's cultural disposition to deprive liberty in criminal justice practices, realistically speaking, is unlikely to be materially reshaped by merely putting plea leniency into use. A retreat from overzealous pre-trial custody requires a paradigm shift rather than a procedural innovation in the system. Of course, the Guiding Opinions urges the procuratorates – when handling plea leniency cases – to cautiously approve arrest should the defendant be deemed to represent a minimal level of ‘social dangerousness’.Footnote 161 In 2021, the People's Supreme Court published its annual work report which highlighted a considerable decrease in the pre-trial detention rate from 96.8 per cent in 2000 to 53 per cent in 2020.Footnote 162 While this marked decline remains unexplained and should be taken cautiously against concerns over the accuracy of Chinese official data, it simply does not tally with the public records in the present study. Across all cases going through the simplified and fast-track procedures, only 1,332 cases (out of 13,611 cases) handled by the Shanghai courts appeared to involve the use of ‘guaranteed release pending trial’ (Qubao Houshen) – a non-custodial measure which allows defendants to return home and attend the court hearing at a designated date.Footnote 163 Because not every court judicial document examined revealed details on the pre-trial status of suspects (in custody or released pending trial),Footnote 164 it was reasonable to surmise that the actual number of defendants granted partial freedom on the Chinese version of bail would be somewhat higher than that reflected in the observed cases. In any event, however, they represented a significant departure from the figure (53 per cent) presented by the authorities. Figure 6 and Figure 7 include five common types of crime under which defendants were most likely to be detained and granted guaranteed release pending trial.

Figure 6. Five Common Types of Crime under which Defendants were Detained prior to Trial

Figure 7. Five Common Types of Crime under which Defendants were Released Pending Trial

The statistical overlap between these two sets of crime is evident. An individual charged with theft (22.3 per cent vs 13.5 per cent), fraud (10.4 per cent vs 9.8 per cent), dangerous driving (12.5 per cent vs 28 per cent) or picking quarrels and provoking trouble (9.1 per cent vs 7.9 per cent) was likely to end up with either an arrest or guaranteed release pending trial, depending in large part on how police exercise their discretion in a specific case. At the outset, this blurred distinction between liberty and captivity is demonstrative of an irregular and incongruent practice of police coercive powers in like circumstances, even within the same jurisdictional region. More ominously, it suggested scanty efforts by the State to ensure that defendants travelling through the plea leniency process were treated more respectfully than in ordinary criminal proceedings. That said, the finding that pre-trial detention prevails over the simplified and fast-track procedures does not represent a rupture of China's preeminent ideology of what Susan Trevaskes incisively terms ‘heavy penaltylism’ (Zhongxing Zhuyi).Footnote 165 On this view, pre-trial detention was not only an approach to serving precautionary purposes, but also ‘a deliberate tool of punishment to deter potential criminals’.Footnote 166 Indeed, the pervasiveness of harshness in China's criminal justice was not invariable and always omnipresent. There was growing evidence that the notion of penal moderation has in some way begun to have a bearing on run-of-the-mill law enforcement in recent decades.Footnote 167 But the steadfast practice of resorting to incarceration as the primary way of policing laid bare flaws in the plea leniency system wherein the presumption of innocence and the principle of ultima ratio appeared to be circumvented ab initio. It dishonoured the defendant's basic right to liberty and other associated rights that would otherwise be more likely enjoyed had the defendant been released prior to trial (eg, the right to counsel). Worse, the overuse of pre-trial detention engendered a generally accusatory environment ripe for forced confessions. As the data suggested, this trend remained largely intact even during the Covid-19 pandemic. What then is required for more liberal treatment of accused is all but the willingness of these criminal justice agencies to refrain from themselves indulging in predetermining guilt, and to act genuinely as neutral and respectful enterprises that champion procedural fairness.

Needless to say, this discursive shift was arduous not least because the practice of legal authorities displayed a deeply entrenched nature of paternalism or despotism. Yu Mou's inquiry into the tactics used by procuratorates to procure guilty pleas disclosed a systematic use of duress, threat, pressure, or persistent importunity that dominated plea leniency meetings with criminal suspects.Footnote 168 In the eyes of prosecuting officers, the defendant was in an inferior position to the State party; hence her deference to authority was not only expected but also required.Footnote 169 Therefore, any confrontational behaviour or attitude from the defendant was readily depicted as ‘a wish to escape punishment by not telling the truth’, and to be dealt with in a manner described as ‘iron-fisted’.Footnote 170 Antithetical to norms of courteous interactions with the accused as encouraged in Tyler's procedural justice formula, Chinese procuratorates, according to Mou, were committed to overbearing and other paternalist strategies – often exemplified by ‘bitter tones, foul language, intimidating body language and slamming furniture’ – to obtain guilty pleas.Footnote 171 While ordinarily, procuratorates were not engaged in physical violence, their approach to defendants stood opposite to respect and thoughtfulness. Therefore, if at the macro level the institutional impediments to respectful treatment of defendants were axiomatic (eg, the overwhelming use of pre-trial detention), handling defendants with respect at the micro level can only be more far-fetched. All things being equal, the problem was not that procuratorates (or by extension all other legal authorities) have discretion to calibrate their conduct in plea leniency. Rather, the problem at issue was that procuratorates were the only one with discretion in this trial-avoiding and supervision-free process.

Trustworthiness – Are Defendants’ Interests and Needs Considered?

The procedural justice theory posits that respect with which the accused is afforded is the most important antecedent of both procedural justice assessments and judgements about the trustworthiness of motives of legal authorities.Footnote 172 In general, trustworthiness is symbiotically associated with respect. It refers to the degree to which an individual perceives that an authority is concerned about her well-being and acts to serve her best interests through sincerely helpful, respectful, and caring actions.Footnote 173 Thus, perceived trustworthiness is enhanced when legal authorities demonstrate that they are motivated to take into account and accommodate the interests of defendants in the decision-making process.Footnote 174 Translated in the plea leniency context, this can be illustrated in express efforts of authorities to address any claims asserted by defendants in support of more lenient treatment. Specifically, the defendant's ultimate hope to receive a less severe sentence in return for her guilty plea ought to be sensibly responded in order to reflect the spirit and crux of plea leniency.

Yet, the limited amount of scholarship on everyday practice in the plea leniency system makes any assessment of trustworthiness difficult. As discussed earlier, defendants generally lack opportunities to voice their position when interacting with legal authorities. Due to neglect, indifference, or venality of police, procuratorates, and counsel, defendants are denied a genuine conduit to make their positions articulate and apprehensible. While it may be convenient to attribute the quandary of trust-building to the inadequate functions of legal stakeholders, the greater force at play lies in the unequal power structure that undergirds plea leniency, which also more broadly defines the workings of China's criminal justice system.

At a glance, the plea leniency model in China bears some practical resemblance to the Anglo-American version of plea bargaining. Both practices are aimed at offering leniency in one way or another to the accused who admit guilt whilst accelerating justice delivery. Therefore, reaching a plea agreement with the prosecution in theory guarantees the defendant a reduced sentence and a much quicker turnaround time. And yet, likening plea leniency to plea bargaining seems cursory and overlooks the characteristic feature of the former which sets it apart from the latter. Fundamentally, the Chinese model of plea leniency is configured solely as one of granting leniency to those who show cooperation, rather than as a transactional exchange of leniency for a light sentence. If plea bargaining allows the defendant to negotiate charging and sentencing concessions to a certain degree,Footnote 175 there is no deviation from the appropriate charges in the exercise of plea leniency. Put differently, plea leniency forbids charge bargaining and only affords defendants nominal leeway to discuss lenient sentencing options.Footnote 176 In this respect, most scholars view plea leniency as a unilateral and illiberal procedure – the legal authorities dictate what charges to file based on already ‘clear facts and sufficient evidence’ and then gauge a narrow discounted range should the defendant plead guilty.Footnote 177 From an official standpoint, this arrangement is justified – it prevents plea leniency from functioning as ‘a corrupt program where justice can be negotiated’.Footnote 178 To maintain the dominant position of legal authorities in steering guilty pleas is to preserve the state authority in discovering ‘objective truth’ which professedly sustains the integrity of justice. Thus, unlike plea bargaining which turns on an adversarial orientation in the criminal process, plea leniency conforms to a larger culture of criminal justice in China – the State exercises monopoly over investigation, prosecution, and adjudication to ‘justly’, swiftly, and severely, if necessary, punish crime.

An authority-orchestrated criminal process, however, marginalises the role of defendants. Calls for lenient treatment are then answerable only when and unless they commensurate with the State's higher purpose of crime control. This is consistent with several findings in the nascent literature on plea leniency – guilty pleas do not necessarily foreshadow lenient sentences as anticipated. In an empirical study based on 6,876 judgment documents on the crime of intentional injury across the country, Fang Wang and Liang Guo found that the act of confession did not contribute to the overall leniency in punishment due to, in principle, a considerably high degree of discretion enjoyed by Chinese courts in determining the appropriate sentence.Footnote 179 Though a set of nationwide guidelines for calculating sentences have been introduced since 2008,Footnote 180 criminal sanctions are susceptible to the illogical sentencing practices of judges in accordance with the particulars of the case concerned.Footnote 181 It is important to note that the data examined in this study only covered the first year of plea leniency (ie, 2017) and did not abundantly capture the marked changes to this very program which factually shifted the sentencing power from courts to procuratorates.Footnote 182 Such shortcomings were overcome in a more recent study using a disparate research setting but generating a same conclusion. Drawing upon about 20,000 driving under influence cases in Fujian Province between 1 June 2013 and 31 January 2019, Yuhao Wu identified an unexpected intensification of penal severity as measured by probation decisions and the length of sentences.Footnote 183 Specifically, his findings recorded a steady decrease in the probation ratio following the induction of plea leniency. As a result, instead of receiving softer criminal penalties, the defendants who had pled guilty were more likely to be sentenced to jail.Footnote 184 Although their declared sentences appeared to be shorter than before, the term they actually served in jail increased by 0.41 months.Footnote 185

The selected data of court judgments in Shanghai also point to the prevalence of imprisonment sentences in plea leniency-initiated summary trials. The descriptive statistics show that probation in all 13,611 cases is not under-represented (n = 6,480). But meting out incarceration for both serious and minor offences manifest itself as a more palpable pattern of sentencing in China's plea leniency programs. At this juncture, the recurrent imposition of jail sentences in the simplified procedure might be comprehensible, given that the majority of offences falling through this process were those legislatively punishable by imprisonment of three years and more. However, the lower proportion of probation vis-à-vis imprisonment in the fast-track procedure where non-violent and property-related offences constituted the largest pool of processed offences reaffirms the prior finding that guilty pleas and lenient sentences are not mutually interdependent. It is true that this statement is but a numerical observation of the raw data and does not involve the difference-in-differences estimation comparing the status quo to the past. Additionally, in contrast to the striking rate of pre-trial detention, imprisonment sentences were less widely applied where plea leniency is in action. What is problematic, though, is the State's continuing penchant for imprisonment as a means of carceral control over defendants deserving of light punishment because they accepted responsibility through guilty pleas and were unlikely to pose further risk to society. Table 8 and Table 9 list two primary risk factors (recidivism and the severity of crime) associated with the offenders who were sentenced to imprisonment.Footnote 186 Both tables indicate that the risk levels of defendants bore little relevance to final sentencing decisions between incarceration and probation.

Table 8. Cases Involving Repeat and First-time Offending in which Imprisonment Sentences were ImposedFootnote 187

Table 9. Three Top Common Types of Crime under which Offenders Received Imprisonment Sentences

As Table 8 shows, despite the finding that first-time offenders were over-represented in plea leniency cases, jail sentences were preferentially selected by judges. This sentencing paradigm was apparent in serious offences but particularly visible in the processing of minor offences. Table 9 presents the top three types of crimes – theft, dangerous driving, and picking quarrels and provoking trouble – where imprisonment sentences were most commonly awarded. Amongst these crimes, defendants who confessed to stealing money or property were more likely to be sentenced to prison. The value of the stolen money and property (2,000RMB) seems to be more a jurisdictional matter to determine the court procedure through which the theft cases are heard, rather than a way in which to differentiate the degree of punishment. In both simplified and fast-track proceedings, imprisonment sentences were discretionarily applied to the circumstances whereby the loss inflicted by stealing is either more or less than the prescribed value. These findings can be better understood in conjunction with the reading of a most recent study on the sentencing outcomes for stealing. Based on 1,000 copies of judges’ sentencing decisions, Wanting Liu discovered that a guilty plea was not the most decisive factor determining the use of incarceration or probation on offenders convicted of stealing.Footnote 189 Rather, factors like the length of pre-trial detention, the forgiveness of victims, and the amount of returned property all play more crucial roles in the sentencing decision-making process, which tended to be considered in ways that reflect an ‘instinctive synthesis’ approach to punishment.Footnote 190