State-owned enterprises (SOEs) and how they are governed are widely discussed in contemporary law and economics literature.Footnote 1 The narrative that defines privatisation, corporatisation, and the separation of ownership and regulatory functions as the key prerequisites for a successful SOE governance structure represents the literature's leading approach. This approach has been embedded in national laws and policies across many countries. It is the core principle of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Guidelines that explain the overall objectives of a solid SOE framework and strongly advise countries on how to manage their SOEs effectively.Footnote 2 The dominant concept prescribes the single corporate regime, and almost entirely focuses on corporate SOEs run on a commercial, for-profit basis.Footnote 3 Nonetheless, some legal scholars have scrutinised and questioned this single-minded perspective, emphasising the impact of existing institutional conditions and calling for an alternative understanding of corporate governance dynamics in different SOEs.Footnote 4 Despite a vigorous debate on SOE governance, it almost exclusively focuses on China,Footnote 5 while Russia, being another large state-driven economy, has been overlooked.Footnote 6

This article fills this gap and contributes to the literature by offering a comparative and critical perspective on the state ownership system in Russia. In 2019, Russia was among the top twenty economies by foreign direct investment outflows.Footnote 7 Russia's SOEs represent one of Moscow's main channels of political and economic influence,Footnote 8 and are among the world's most powerful companies in the extractive sector primarily.Footnote 9 The analysis of Russian SOEs reveals classic governance and incentive problems attributable to state ownership. The question is how despite close affiliation to the State and high agency costs caused by state interference, Russian SOEs have gained a substantial international market presence. This article answers this paradox by offering several new insights: first, reasons for the existence of the current state ownership system. Second, the evolution of this system. Third, the rationale behind the system that appears costly but gives rise to the world's largest companies. And fourth, the extent to which the system relevant to other models and particularly China, which is the well-studied example of a politically managed state-driven model.

Since the late 1990s to early 2000s, when Bernard Black and Reinier Kraakman studied Russian institutional reforms, there had been no comprehensive analysis of the dynamics of corporate law and corporate governance in Russian companies and specifically SOEs.Footnote 10 Most international experts and academics who studied Russia at the dawn of its reforms previously assumed that the presence of the State in Russia's economy had a temporary effect that would decrease or even disappear as soon as the market opened up and the formal institutional environment improved.Footnote 11 Today, Russia has been demonstrating the opposite tendency of the ‘reverse’ transition, establishing formal institutions that reinforce the State's growing influence.

The analysis of the most recent forms of Russian SOEs reveals a distinctive and sometimes controversial legal regime. In contrast to many other state-driven economies, including China, Russia's policymakers seem to pay less attention to corporatisation and the separation of ownership and regulatory functions.Footnote 12 The new forms of SOEs are non-commercial and non-corporate entities that are subjected to many statutory restrictions and close oversight from the State. Their governance structure includes supervisory boards, but they are not equivalent to corporate boards since their directors have no real fiduciary duties to the SOE. Directors and top managers are state appointees whose role is to fulfil the goals and targets established by state strategic policies. The State and the Federal Government acting on its behalf are positioned as the ultimate owner, not a shareholder.

The remainder of this article will proceed as follows. It begins with an overview of the contemporary SOE governance literature. The course of legal and corporate governance reforms in Russia are then examined. The article provides the context behind Russia's institutional and economic changes. Next, it analyses different forms of SOEs and scrutinises Russia's state ownership system, its management, and performance. The article grasps the rationale behind the existing system and its relevance to other models, particularly China's. It explores numerous Russian sources that have mostly remained unfamiliar to the international academic community but provided their own scholarly perspective on this topic of global consequence. The article concludes with the call for additional studies.

Theoretical Narrative

SOEs are important actors that often shape the institutional landscape and implement regulatory regimes in their home countries and beyond, giving rise to debates on an alternative approach to development.Footnote 13 However, state ownership causes several major challenges, including political considerations, multiple objectives, and the absence of an effective owner.Footnote 14 These challenges raise concerns about limited autonomy, politicised decision-making, weak profit incentives, and inefficient performance management.Footnote 15

As an institutional response, the mainstream approach recommends a sound legal framework that typically means bringing SOEs under a country's company law. The main idea is to expose SOEs to transparent market competition that demands an explicit separation between ownership and management, ownership, and regulation. This approach gives SOEs a higher degree of operational autonomy and managerial flexibility, while requiring SOEs to go through the process of commercialisation and corporatisation.Footnote 16 In particular, the OECD Guidelines prescribe several key measures.Footnote 17 First, countries should simplify and standardise SOE legal forms by synchronising them with commonly accepted corporate forms and practices existing for private firms. The second step is the centralisation of the state ownership function under a single agency or entity, which, in turn, should be accountable to the legislative body. Third, the OECD Guidelines call for an independent and professional board that acts in the company's interest and is subject to the same legally enforceable duties as the board in a private company. Finally, SOEs are strongly encouraged to maintain adequate transparency and disclosure to allow investors, customers, and independent auditors to monitor important financial and operational information.Footnote 18 The idea behind these recommendations is to introduce a corporate governance regime that disciplines directors and managers and establishes a clear separation of ownership and regulation. It attempts to constrain state interference and promote the principles of higher market value and cost-efficiency.Footnote 19

However, corporatisation is not a perfect recipe that automatically leads to better SOE performance. Corporatisation does not necessarily guarantee better performance when soft budget constraints, political interference, and insufficient markets still exist. To make the system work, countries should implement a series of complex institutional reforms accompanied by the mindset shift among government officials and SOE managers. As a result, the real effect of corporatisation varies from country to country, and from an SOE to an SOE.Footnote 20

Another legitimate question is whether the single regime should govern various legal forms of SOEs with different goals. Most of the studies tend to apply the lens of the single corporate governance model and focus on its benefits. The single regime is deemed to mitigate SOEs’ unfair competitive advantage and increase their value by applying standards and norms similar to private firms.Footnote 21 However, this concept does not pay sufficient attention to whether those standards are relevant to the nature of SOE's agency problems, their actual allocation of powers, and the overall quality of governance institutions in a particular country.Footnote 22 The empirical studies of SOEs demonstrate no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach and no universal governance practice. The choice of an applicable framework depends on the context of an individual country or even an individual SOE. This means that for their successful application, the best governance practices should adapt to and corresponds with an existing socio-economic and legal context. Otherwise, the adverse effect of ignoring the context can disrupt SOEs’ performance and bring about a significant risk for the sustainability of state-driven economies.Footnote 23

Background and Legal Framework

Corporate governance evolution in Russia

Corporate governance has been broadly discussed throughout the entire history of post-Soviet Union Russia.Footnote 24 As the Russian markets and legal landscape evolved, companies were facing different issues. Along with economic modernisation, the corporate governance framework and company law were developing relatively quickly and often fragmentarily. The role of corporate governance transformed due to macroeconomic factors, institutional changes, and legal reforms – all of which have contributed to the Russian corporate governance model. The overview of existing literature roughly distinguishes several stages of the evolution of ownership and corporate governance in modern Russia. Each stage demonstrated particular characteristics and trends triggered by institutional, political, and economic shifts that took place over those years.Footnote 25

The first stage is typically associated with the initial privatisation program and structural reforms introduced in the early 1990s. The main body of studies around that period focuses on the privatisation of state property and its outcomes.Footnote 26 They emphasise the lack of institutional conditions for the new privatisation policy to become successful.Footnote 27 In the early 1990s, there were no legitimate, effective, and transparent corporate governance practices and laws.Footnote 28 As a result, the ownership of privatised companies became locked in the hands of insiders with the real power exercised by management.Footnote 29 Employees could not fully appreciate the benefit of being shareholders because of the absence of liquid securities markets and adequate property rights protection.Footnote 30 When managers obtained the status of dominant or single shareholders, ownership, and management merged. The shareholding concentration produced strong managerial power, non-transparent decision-making processes, self-dealing, and the weak legal protection of a very few remaining minority shareholders.Footnote 31 The mid-1990s finalised the concentration of shares in large blocks held by the single shareholder or a group of shareholders, who primarily relied on internal capital resources. That stage can be marked with the launch of the new Civil Code of 1994, followed by the new laws on joint-stock companies of 1995 and limited liability companies of 1998.Footnote 32 Those laws represented the first attempt to design a legal basis for corporate governance in Russia.Footnote 33

The second stage commenced in the early 2000s, when an average controlling shareholder share reached 40 to 50 per cent, with two-thirds of joint-stock companies having a controlling shareholder.Footnote 34 Predictably, corporate governance focused on the interests of controlling shareholders. The rise of controlling shareholders deepened their tension with the interest of minority shareholders. Those conflicts called for new legal norms and institutional standards to mitigate a chance for corporate abuse.Footnote 35

New legal requirements were not the only incentives for companies to enhance their corporate governance practices. During that stage, companies reached the maximum of their internal financial capacities.Footnote 36 At the same time, Russian capital markets continued to emerge and offered limited opportunities for companies to raise additional funding. In those circumstances, the priorities shifted towards the exploration of new financial sources. Corporate governance became a significant factor that assisted companies with access to capital markets. The adherence to best practices and international standards, including independent directors and professional boards, fair treatment of minority shareholders, and effective conflict resolution mechanisms, helped companies improve their reputation and build trust with investors and creditors.Footnote 37 The potential access to new funding strengthened the Russian corporate sector's incentives to mitigate information asymmetry and moral hazard problems. In 2002, Russia approved the Code of Corporate Behaviour.Footnote 38 Several non-government organisations, including the Association for Investor Rights Protection, Corporate Governance Supervisor Council, Independent Directors Association, and the Russian Institute of Directors, emerged during that period. In 2001–2002, the capitalisation of the Russian securities market started to grow and reached US$127 billion by 2003.Footnote 39 The number of IPOs of Russian companies and the amount of attracted capital demonstrated a constant increase.Footnote 40

Another trend of the early 2000s was the Federal Government's attempts to consolidate unitary enterprises and blocks of shares under the management of state holding companies. The Federal Government launched reforms to optimise state assets, increase state control in companies with mixed ownership, and deepen connections between the political establishment and business leaders loyal to the political regime.Footnote 41 Those processes were accompanied by the Federal Government's acquisitions of several large private companies.Footnote 42 The general tendency of expanding the state share in the economy became more evident and steadier after the financial crisis of 2008. The growing state share also contributed to further ownership concentration.Footnote 43

The third stage began with the crisis of 2008 that caused the collapse of the domestic securities markets and severely affected large public companies.Footnote 44 Adherence to better corporate governance was no longer enough to attract investments, and the focus shifted to higher efficiency and organisational effectiveness in terms of existing resource capacities. Although the number of companies striving to comply with the best corporate governance practices was increasing over the years, the overall quality of corporate governance remained relatively low.Footnote 45 In 2016, the Federal Government adopted a roadmap for eliminating legal loopholes and improving the corporate governance system, including minority shareholders protection.Footnote 46 Russia approved laws on the illegal use of insider information and market manipulations, amended laws on joint-stock companies and securities markets, and reinforced administrative liability for financial violations and misconduct.Footnote 47

The expansion of the Russian state sector

By the end of the 1990s, the State's presence in the economy was widely spread across various sectors in the form of unitary enterprises and newly created joint-stock companies.Footnote 48 In the 2000s, the Federal Government made an effort to increase the management efficiency of its dispersed assets by consolidating them in state holding groups.Footnote 49 As a result, several state corporations emerged in 2007 to 2008, including Rosnanotech, Rostekhnologii, and Rosatom. Simultaneously, the Federal Government defined a few ‘trusted’ private group companies to maintain the oversight under a specific industry.Footnote 50 The period of 2004 to 2006 marked the return of strategically important companies under state control.Footnote 51

A steady trend towards the state's dominance in the leading sectors of the Russian economy continued in 2007 to 2008, with the reduction in the number of unitary enterprises, the integration of state assets into holding companies, and scaling up those companies and their business interests through acquisitions.Footnote 52 In 2010, the total share of SOEs in the RTS index was about 54.5 per cent, including about 89.5 per cent in the financial sector, 66.5 per cent in the oil and gas sector, and 61 per cent in the power supply sector.Footnote 53 As a result of the financial recession of 2008 and the following anti-crisis measures,Footnote 54 the state's share in GDP grew from 41.2 per cent in 2008 to 51.8 per cent in 2009.Footnote 55 By 2012, Russia owned shares in more than 2.5 thousand joint-stock companies.Footnote 56 The consolidation of state ownership raised several concerns among experts and academics. The expansion of state and quasi-state structures was associated with typical negative effects triggered by state ownership, including low profitability, market distortions, limited competition, and non-transparency.Footnote 57 The statistics showed that out of 2.5 thousand companies owned by the State, only 60 companies were profitable in 2011, while 22 per cent of joint-stock companies demonstrated losses.Footnote 58

The sanctions of the US and the EU expedited the State's expansion.Footnote 59 Recently, Western countries have vetoed mergers and acquisitions involving Russian companies.Footnote 60 Several joint venture projects with Russian banks and investors have been terminated.Footnote 61 Even Russian companies that do not appear on the sanctions list suffer from political tension. Large European and US corporations have received a warning to supply equipment and technologies to their Russian counterparts.Footnote 62 The opportunity to attract long-term funds for projects in Russia has diminished, depriving Russian companies of access to technologies and capital from the West.Footnote 63 Sanctions against Russian companies facilitated the reliance on state funding and the creation of new SOEs.Footnote 64 In 2015, the Russian Government had to put extra funds to support domestic enterprises affected by the sanctions.Footnote 65 According to the Minister of Finance of the Russian Federation, if the economic situation worsens, the Russian Government plans to allocate more than 60 per cent of the National Welfare Fund to support the economy.Footnote 66

The Federal Antimonopoly Service of the Russian Federation revealed that the combined contribution of SOEs to Russia's GDP in 2015 was about 70 per cent, while that share did not exceed 35 per cent in 2005.Footnote 67 In 2018, that share reached 60 per cent.Footnote 68 Limited domestic data on the state share in the economy generates mixed numbers. Although those numbers can vary, the tendency towards the state share's growth is evident and calls for a comprehensive analysis. The following paragraphs discuss the organisational forms of Russian SOEs.

Organisational forms of Russia's SOEs

Initially, organisational forms of Russia's SOE were limited to socialist unitary enterprises.Footnote 69 Those traditional SOEs operated as means of production managed by the Soviet authorities directly.Footnote 70 They were part of the state planning system and had to deliver specific production targets defined by the State.Footnote 71 The revenues, if any, were transferred to the State's budget.Footnote 72 State unitary enterprises continue to exist in Russia today as a relic of the Soviet management approach.Footnote 73

Asset management and public policy functions were outside the scope of unitary enterprises designed for pure production purposes. As a response to the State's economic expansion, the legislator introduced new types of SOEs: public law companies, state corporations, and state companies.Footnote 74 All three forms share several main commonalities. First, they have a single owner – the Russian Federation and the Federal Government acting on its behalf. Every such SOE is established by a special federal law defining its goals, governance, property rights, and disclosure obligations. Second, they are non-corporate (unitary) and non-commercial legal entities with no equity capital divided by shares and no focus on profit as their primary goal. Third, these SOEs have a number of functions: from public services and public administration to asset management and industrial development. They still can conduct entrepreneurial activities and operate on the market, but only if such activities contribute to and comply with the goals defined by the federal law. These activities are subject to several restrictions and protection measures. In particular, the state owner has the statutory right to approve major transactions and protect SOE property from any creditor claims while avoiding responsibility for the obligations of its SOEs. Bankruptcy laws and procedures do not apply to these forms of SOEs. Fourth, federal laws establish minimum standards for disclosure and transparency. Finally, these SOEs have an identical governance structure that includes a supervisory board as the supreme governing body and a general director (executive board).

The only organisational form of SOEs in Russia, which has a corporate commercial nature, is a joint-stock company (JSC) regulated by the Federal Law of 1995.Footnote 75 Its governance structure, the distribution of rights and powers, capitalisation, and decision-making processes resemble JSCs elsewhere. The State remains the most influential shareholder in terms of its share's size and impact capacities.Footnote 76 The State's influence causes typical corporate governance distortions, including the complexity of goals, the tension between the roles of a shareholder and a regulator, more profound ‘principal-agent’ problems, and weak management incentives. The state can hold a controlling, blocking, or minority share. Figure 1 shows the percentage of SOEs based on the state share's size.Footnote 77

Figure 1. The Percentage of SOEs*

*These numbers are based on Rosstat's data and represent federal ownership.

The shareholder role can be fulfilled by the Federal Property Management Agency (Rosimushchestvo), Federal ministries (ie, the Ministry of Defence or Ministry of Finance), the Central Bank of Russia, state corporations or companies, or municipal authorities. In strategically-important SOEs, the Government of the Russian Federation or the Chairman of the Government of the Russian Federation performs this role.Footnote 78

Due to the growing budget deficit, the Federal Government has been reducing the number of SOEs across different sectors.Footnote 79 However, their substantial reduction over the past five years does not reflect the state's shrinking stake in the national economy, but rather indicates reorganisation processes within the state sector itself, including the growing number of companies with mixed ownership.Footnote 80 When the State becomes a minority shareholder, it utilises several governance tools to protect its interest. In particular, critical shareholder decisions often require a qualified majority of votes, including minority shareholders. The Federal Government can nominate its representative officers and representative members to the board and internal audit commission respectively. The opportunity of cumulative voting increases the chances for these representatives to be elected. The minority share allows the State to call for shareholders meetings, propose an item to its agenda, and access financial and other corporate documents. Finally, the privatisation legislation includes several norms protecting the State's share from future dilution.Footnote 81

When giving up control, the Federal Government can introduce a ‘golden share’.Footnote 82 Its justification is to ensure that the company continues complying with Russia's security interests and protects Russian citizens’ morals, health, rights, and other legitimate interests.Footnote 83 The statistics show that the Federal Government holds ‘golden shares’ in approximately 9 per cent of the total number of its JSCs.Footnote 84 The State can introduce this share from the moment when its shareholding drops below the blocking threshold (25 per cent plus one share).Footnote 85 Ultimately, the State also has the authority to decide on the termination of this right.Footnote 86

Discussion

The separation of ownership and regulation

From the traditional perspective, Russian SOEs appear to be an example of the classic problem of an ‘absent owner’.Footnote 87 There is no single law regulating SOEs, no single set of requirements applicable to them, and no single organisation managing state ownership. State officials, being agents themselves, do not have sufficient economic incentives and autonomy to prioritise SOEs’ financial performance. Only a fraction of Russia's largest SOEs has gone through corporatisation.Footnote 88 The rest of SOEs, including the new organisational forms, are not corporations.Footnote 89 The State employs its administrative power and bureaucratic apparatus to govern them directly and prioritise their policy goals and functions.

The explicit non-commercial nature of the new organisational forms tackles the problem of multiple objectives.Footnote 90 Although federal laws do not mention a single objective but rather outline the list of objectives, they all fall into the state policy agenda, leaving no room for confusion that revenue is not the primary goal. Profit-seeking is allowed, but only if it does not conflict or disrupt strategic policy goals and other development mandates from the State.Footnote 91 To align SOEs toward their strategic agenda, the State has designed a governance structure that controls the nomination, selection, appointment, and rotation of SOE directors and executives and reserves the decision-making power on material issues. The governance structure creates no conflict between the black letter law and the State's actual governance approach.Footnote 92 From the perspective of other market actors, it creates no illusion that SOEs act to pursue commercial and market objectives. This approach distinguishes Russia's SOEs from large SOEs in other countries, particularly China, where corporatisation and the formal separation of the commercial and regulatory functions, ownership and control, have been the continuous focus of SOE reforms.Footnote 93

Blurred distinction among SOE organisational forms

The reference to the term ‘company’ or ‘corporation’ in the organisational forms of a public law company, state corporation, or state company might inaccurately indicate that these legal entities are corporate entities. In other words, it may wrongfully signal that they have gone through a corporatisation process that establishes corporate structures and governance practices typical to a corporate form. A standard corporate entity demonstrates the following key features: first, it has a separate legal personality; second, its shareholders have limited liability; third, its equity capital is divided by transferable shares (stakes); and fourth, its governance structure reflects the idea of delegated management.Footnote 94 The fundamental goal behind corporatisation is to create an arms-length relationship between a corporate entity, existing independently, and its shareholders.Footnote 95

However, neither of the new forms of SOEs demonstrate the full scope of corporate attributes; Russia's civil law does not define them as corporations. Therefore, the reference to a ‘company’ or ‘corporation’ in this case is misleading and causes challenges for adequate comparative studies.Footnote 96 The law provides the State with an opportunity to safeguard the SOEs’ most important assets from creditors exempting these assets from Russia's bankruptcy law. Although the SOEs’ assets are separated from the assets of their founder – the State (as opposed to unitary enterprises, in which the state keeps the property title), the law grants the Federal Government the right to exempt a pool of assets and/or type of assets from creditor claims. Additionally, the Federal Government has the authority to identify the scope of transactions that requires its approval or instruct the board to transfer assets back to the ownership of the Russian Federation if such assets are free from obligations.Footnote 97 The transfer can potentially occur after the SOE has entered a deal and might significantly affect the SOE's financial sustainability.

The State enjoys a wide range of opportunities to challenge the SOEs’ transactions if they do not comply with the State's fiscal and policy interests.Footnote 98 The State does not limit SOEs’ right to conduct commercial activities if those activities comply with the SOE's goals. Notwithstanding the status of non-profit organisations, public law companies, state corporations, and state companies can do business in their respective industries.Footnote 99 They can raise capital on the market, including the issuance of corporate bonds.Footnote 100 However, despite an enormous decision-making authority and interventionalist power, the law releases the State from being financially responsible for its SOEs reinforcing the principles of asset partitioning and limited liability at the expense of creditors.Footnote 101 The legal prioritisation of the State's interests over creditors’ interests creates unequal conditions for state and private market actors. It disrupts constructive market signals, equal access to information, effective capital allocation, and other principles of a free market economy. Therefore, legal norms institutionalising this prioritisation are not compatible with fundamental market standards as well as Russia's constitutional principle of the equal protection of property rights.Footnote 102

Substantively, it is challenging to distinguish among the three forms since they share similar status, objectives, functions, and governance structures. Even if the Federal Government is assumed to perform the role of a single shareholder, it is inherently wrong. In any corporate structure, a single shareholder may decide to split control or raise additional equity investments through private or public offerings of shares. As a result, new shareholders acquire the same rights to participate in the management and receive dividends on the one hand, and bear the same risk of losses equal to their stake on the other. However, this scenario is impossible for public law companies, state corporations, and state companies. The only way these SOEs can raise equity capital is to appeal to their founder.

From the dual role perspective, the new forms of SOEs can not only do business in their industries but also regulate them.Footnote 103 This peculiarity creates the potential for market and regulatory distortions as well as the abuse of powers by those SOEs while initiating investment projects, launching new regulations, granting licenses, or providing access to financial resources. The lack of legislative and conceptual distinctions among SOE forms ultimately leads to difficulties with evaluating their performance and finding efficient governance solutions. Although the governance system of the new forms of SOEs may bear some resemblance to traditional corporate governance, it is not corporate governance per se.

SOE performance management

One of the challenges typically associated with SOE performance is the presence of both commercial and non-commercial objectives.Footnote 104 The non-commercial goals have financial costs but do not generate revenue, making it difficult for an SOE to meet its financial targets. Mixed objectives cause information asymmetries that can impede effective monitoring and allow managers to justify poor performance.Footnote 105 A sound performance management system addresses these asymmetries and incentive tensions by distinguishing financial and non-financial objectives and clearly articulating non-financial objectives.Footnote 106

In 2015, President Vladimir Putin emphasised the need to review the existing management system for SOEs in his Annual Address to the Federal Assembly.Footnote 107 The President instructed the Federal Government to introduce new metrics of key performance indicators to reinforce a direct link between the remuneration of senior management and the achieved financial results.Footnote 108 Followed by the President's message, the Federal Government attempted to systematise and enhance its approach to SOE performance. Rosimushchestvo has approved a series of mandatory guidelines for increasing investment and operational efficiency, optimising cost reduction, and developing key performance indicators (KPIs) by SOEs.Footnote 109 In particular, the guidelines on KPIs segment SOEs depended on their organisational form (JSC, LLC, unitary enterprise, or state corporation), financial performance, and sector. The guidelines empower every SOE to determine an optimal combination of prescribed financial and industry-specific (non-financial) indicators.Footnote 110 Also, notwithstanding the state share's size, all JSCs are subject to the State program of the federal property management approved by the Federal Government in 2014.Footnote 111 The program targets the reduction of the State's engagement in the ownership and governance of SOEs.Footnote 112

SOEs remain the key instrument of the strategic development and planning system designed by the Federal Law of 2014: ‘On Strategic Planning in the Russian Federation’.Footnote 113 This Federal Law requires SOEs to subordinate their plans and investments to the state strategies, including the national security strategy, the socio-economic development strategy, the spatial development strategy, and regional strategies. The Ministry of Economic Development and Rosimushchestvo are responsible for aligning SOEs’ strategies and performance.Footnote 114 Since the early 2000s, these two state agencies have offered several packages of recommendations and guidelines.Footnote 115 However, the lack of consistency and coherence among strategic goals at the federal level and potentially different expectations and agendas supported by government agencies cause a serious coordination problem.Footnote 116

The non-profit focus of the new forms of SOEs created another challenge: the tension between SOEs’ objectives and their portfolio companies’ interests, which affects the design and delivery of performance indicators. While the new forms have broader development policy targets, their portfolio includes commercial corporations that derive most of their revenues from the market. The presence of conflicting objectives in the group leads to different performance expectations, which in turn creates challenges for adequate performance management. The result is a very complex management system with multiple indicators that can deteriorate performance and innovation. Recent studies show that Russian companies have achieved little progress in offering innovative products to the domestic and international markets.Footnote 117 The share of Russian enterprises on the global market for high-tech products was only 0.3 per cent.Footnote 118 The most powerful extractive sector does not demonstrate high performance management efficiency. The largest public SOEs Gazprom and Rosneft occupy leading positions on the Russian and international energy markets.Footnote 119 However, studies of the two companies from 2013 to 2015 found no direct or strong correlation between management remuneration and the companies’ financial and production performance.Footnote 120 When a high level of remuneration is guaranteed regardless of the company's financial results, there is no real incentive for the top management to improve economic outcomes. Although both companies adopted key performance indicators for senior management, the studies found no real effect.Footnote 121 Another study of SOEs in Russia demonstrates that although 91 per cent of SOEs link top management remuneration to the company's financial results, this correlation is mostly relevant to short-term results (77 per cent).Footnote 122

One explanation of the weak correlation between remuneration and performance is the practice of state formal directives discussed in the following section.Footnote 123 This practice mitigates the board's ability to exercise business judgement and substantially limits its incentives to improve SOEs’ financial performance. The study conducted by the Russian Institute of Directors indicated that state directives often appear to be generic and do not consider the specific characteristics of each SOE. Also, there might be a lack of consistency among directives issued by different state agencies.Footnote 124 All these factors undermine SOE's financial performance and raise the question of the role of the SOE board in decision-making.

SOE supervisory boardFootnote 125

Professional boards of directors are the major elements of a sound corporate governance structure.Footnote 126 Board members usually acquire extensive commercial, financial, and strategic knowledge and skills to exercise their business judgment effectively. The design of robust and transparent practices for well-functioning boards ensures that board members possess the necessary competencies and independence to fulfil their duties.Footnote 127 In this regard, governments intentionally limit their interference in corporate matters to increase autonomy and secure the unbiased business judgment of SOE boards, creating a system of checks and balances that deals with agency conflicts. It is also assumed that the interests of an SOE and its state shareholder are inherently different, especially in corporate commercial SOEs.Footnote 128 In Russia's non-corporate non-commercial SOEs, their governance bodies implement one fundamental purpose: the strategy of an ultimate owner and decision-maker – the State. There is no traditional conflict of objectives since the only interest that matters is the State's interest. In this scenario, the role of the board becomes much less strategic and more instrumental.

The general criticism of the weak board typically emphasises the State's potential to intervene in its activities.Footnote 129 An empowered board can offset the State's opportunistic behaviour and limit its interference.Footnote 130 However, in Russia's non-corporate non-commercial SOEs, the board adopts and implements the strategy that has been pre-defined by the State and endorses executives selected by the State.Footnote 131 Government policies and decisions frame the board's powers. The board's role transforms into a watchdog, which administers the State's assets, supervises the strategy's implementation, and supports the general director. This role drives the incentives, determines the qualification requirements of the board members, and shapes performance expectations.

The existing practice of voting based on formal directives issued by the state reinforces this trend. Formal directives are the central element of the state management system. They are administrative acts addressed to state representative officers and expressing the state shareholder's will at the general meeting of shareholders or board meetings. The procedure for issuing formal directives is subject to administrative laws.

The extent to which the directives influence SOE governance and decision-making depends on two factors: the size of the state share and the status of an SOE (publicly traded or nonpublic, strategic or non-strategic). In particular, the Federal Government selects and appoints the entire board in state corporations and JSCs solely owned by the State. In JSCs, in which the State shareholder (typically Rosimushchestvo) holds more than 25 per cent, it can select and nominate its representative officers to the board.Footnote 132 These representative officers can be government officials, civil servants, or professional directors. In the latter case, they receive remuneration and act based on an agreement.Footnote 133 This agreement describes the representative officer's rights, duties, and liability. The scope of the duties includes: first, timely informing their principal on issues requiring state directives; second, voting strictly per directives; third, calling for a board meeting when it is necessary, and lastly, participating in board meetings and proposing items to their agenda.Footnote 134 These duties largely focus on compliance rather than an independent business judgement. Representative officers essentially are not corporate directors. Instead, they play the role of state administrators obliged to follow formal directives defining their decisions and responsibilities.Footnote 135

The non-fulfilment of the duties leads to the unilateral replacement of a representative officer by the authorised state agency.Footnote 136 Also, representative officers can be held personally liable for their failure to comply with their duties.Footnote 137 It is worth mentioning that personal liability applies to all directors and officers of the companies in which the State holds a controlling share and their subsidiaries. It also applies to the officers of companies in which the State has a ‘golden share’.

Ironically, the Russian Institute of Directors’ survey demonstrated that the majority of SOE directors are in favour of maintaining formal directives. In particular, 79.1 per cent of SOE directors assessed this practice as acceptable, and 74.8 per cent of respondents even believed that the abolition of this practice would cause management risks.Footnote 138 Among the main positive aspects of formal directives, SOE directors highlighted the possibility of safeguarding federal property, fulfilling the state shareholder's will, and protecting directors from liability in the absence of liability insurance and profound regulation.Footnote 139

The extent to which the existing practice of formal directives influences SOEs’ financial and economic activities is not clear.Footnote 140 However, it is quite apparent that formal directives can potentially deprive SOE directors of the opportunity to play a traditional and meaningful role in governance.Footnote 141 Despite several reforms related to corporate boards in Russia,Footnote 142 those changes have been fragmentary and unsystematic, mitigating the overall positive effect.Footnote 143 For instance, while the number of SOEs with independent directors grows,Footnote 144 the share of SOEs in which independent directors comprise more than one-fourth of the board still did not exceed 49 per cent.Footnote 145

Rationale, Characteristics, and Relevance

Previous sections expose several classic flaws of Russia's state ownership system: no separation of ownership and regulatory functions, inadequate performance management, and non-professional boards. All these factors are considered to raise the agency costs of Russian SOEs and undermine their financial performance. Then, the legitimate questions are: first, what is the rationale behind the system that appears to be costly, and second, how Russia's SOEs can operate on the market and be among the world's largest companies?

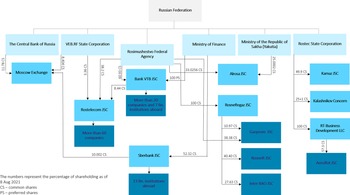

All recent legislative amendments illustrate the Federal Government's attempt to find efficient organisational forms to manage state assets.Footnote 146 Since state ownership occupies the central place in Russia's economy, creating an effective management system for SOEs becomes critical. At the same time, Russia's system of SOEs is decentralised. The key federal property owner is the Federal Government or the Federal Agency for State Property Management (Rosimushchestvo) which reports to the Government of the Russian Federation. The second category is represented by state corporations (for example, Rostec, Rosatom, or VEB.RF) which are the major owners of assets transferred to them by the State. The third main category includes the Central Bank of Russia, Federal ministries (particularly the Ministry of Defence and the Ministry of Finance), and municipal authorities. Figure 2 offers an illustration of the existing ownership system.

Figure 2. An illustration of Russia's shareholding system.

When the shares of SOEs remain federal property, the State's governance approach depends on the non-strategic or strategic (special) status of an individual SOE. In the latter case, the model becomes more complex. It requires the engagement of the Presidential Administration, Federal ministries, and Rosimushchestvo to reach an agreement on crucial shareholder decisions finalised by the Federal Government. In SOEs with no special or strategic status, Rosimushchestvo has the right to exercise shareholder powers independently.Footnote 147

Another factor determining the State's governance approach is the percentage of shares owned by the Russian Federation. When all shares belong to federal property, the Federal Government or Rosimushchestvo (depending on the strategic status of an SOE) replaces the general meeting of shareholders. Their decisions become the decisions of the single shareholder. The State typically holds a hundred percent of shares in the military industry and the most critical elements of infrastructure – railways, energy facilities, and post office, etc.

When the Russian Federation has a controlling, minority, or ‘golden share’, the Federal Government or Rosimushchestvo appoints its representative officers participating in general meetings of shareholders and board meetings, voting per formal directives, and reporting to the Federal Government or Rosimushchestvo. To improve communication with representative officers, Rosimushchestvo has introduced a special channel – MV Portal. The portal's single informational space allows all authorised participants to access the state asset management data in real time. The portal offers the opportunity to interact and exchange information, monitor the implementation of directives, and report on specific instructions from the President of the Russian Federation and the Federal Government.Footnote 148

State corporations are the second category of SOE shareholders. The expansion of the State's presence in the national economy and the call for the more effective governance of state assets resulted in the emergence of state corporations designed to manage and control a large pool of different organisations. The new forms of SOEs appear as a combination of corporate governance, market, and administrative instruments. For instance, Rosatom and Rostec are state corporations that manage a broad portfolio of companies through participation in authorised capital. The portfolio of Rosatom and Rostec resembles a classic holding company structure that governs subsidiaries and affiliated organisations based on direct, indirect, or cross-shareholding. Both groups serve state interests in strategically important sectors. They are platforms for the implementation of the State's development programs and investments.Footnote 149 They accumulate significant financial and production resources which they then distribute across different industries based on the existing market and the country's socio-economic needs.

The main feature of Russia's state group model is its heterogeneous nature in terms of industries, business activities, legal entities, their status (strategic or non-strategic), and goals (commercial and non-commercial). The core idea of the model is better governance by introducing market forces, inviting professional management expertise, and mitigating the bureaucracy of administrative processes.Footnote 150 The model exposes the groups to domestic and, more importantly, international market competition to boost incentives to innovate. It integrates SOEs into different industries and production chains to assist the Federal Government with regulation and monitoring when legal norms fail to function effectively.

As mentioned in the previous section, state corporations and other large SOEs do business in their industries and, de jure or de facto, regulate them. For instance, Rosatom is legislatively empowered to implement a public administration function related to the usage, licensing, development, production, and disposal of nuclear weapons and nuclear power. The state corporation issues legal acts regulating the industry's control, standardisation, and certification. At the same time, Rosatom's group includes more than 140 companies (out of which, approximately 100 are commercial JSCs and LLCs), including several commercial companies established overseas under foreign law. The group is among the world's leading producers of nuclear energy and uranium.Footnote 151 The overseas companies explore new business opportunities and manage Rosatom's portfolio worldwide, including Central Asia, Africa, and the US.Footnote 152

Another example is Rostec – a state corporation established by the Presidential decree in 2008 ‘to support Russia's industrial complex through hard times and make domestic industries competitive on the international market.’Footnote 153 Back then, the Federal Government transferred 426 legal entities to Rostec's group. About half of those entities were insolvent, experiencing financial losses, or undergoing bankruptcy.Footnote 154 Many of them represented Russia's military industry. Over ten years, the group could grow its production and revenue, launch non-military projects and new businesses, expand its international contracts portfolio and export. The total revenue of Rostec grew from RUB 511 billion in 2009 to RUB 1,771 billion in 2019.Footnote 155 Today, Rostec's group includes 25 large holding companies.Footnote 156 These holding companies operate in various business sectors: from investment banking and business development to car manufacturing, from pharmaceuticals to information security. They are JSCs with a clear commercial agenda that export their products and services to 70 countries.Footnote 157

The Federal Government and the Presidential Administration control both groups through their parent companies: Rostec and Rosatom. The parent company manages its group independently through a single or controlling shareholding and board representation. Every company in the group (except for several unitary enterprises) is a separate legal entity with fundamental corporate attributes, including limited liability and asset partitioning. Group companies are established and regulated by corporate law norms and corporate governance practices, not administrative rules and processes.

Therefore, the existing model of Russia's SOEs represents a compromise: exercising close control over strategic SOEs while taking advantage of market infrastructure and some contemporary corporate governance practices. Initial organisational forms inherited from the Soviet legacy did not provide the State with enough flexibility and freedom to raise capital, restructure assets, and take business risks domestically and internationally.Footnote 158 In contrast, traditional corporate forms could hardly control negative externalities and created barriers to direct oversight that the political leadership intended to preserve.Footnote 159 However, it is doubtful that the existing model is efficient. The efficiency argument relates to the model's design and implementation. A recent report issued by the Accounts Chamber of the Russian Federation emphasises that the model suffers from several major shortcomings.Footnote 160

First, there is no reliable source of data on the number of SOEs in Russia. Rosimushestvo, Rosstat, and the Federal Tax Service offer contradictory statistics. The absence of adequate and reliable data hinders the analysis of SOEs’ governance, performance, and real impact on the national economy. The Federal Government focuses on a narrow circle of the largest and most strategic SOEs securing a substantial budget revenues inflow.Footnote 161 Since 2017, the 20 largest JSCs have contributed 97 per cent of the total dividends received by the federal budget, while other SOEs have been hardly monitored.Footnote 162

Second, decentralised governance and a heterogeneous pool of SOEs add to the problem of poor data. Different state bodies and organisations supervise Russia's SOEs. These SOEs vary depending on the state share's size, strategic or non-strategic role, commercial or non-commercial focus, market capitalisation, monopolistic status, and revenue flows. Multiple governance actors represent diverse interest groups and advocate for different results. The multiplicity of actors brings about no consistent approach to SOE governance.

Third, despite the opportunity to select professional directors and experts, civil servants and state officials are still the largest groups of state representative officers (almost 50 per cent of their total number).Footnote 163 The remuneration of SOE managers does not depend on their companies’ financial results creating incentive disparities.Footnote 164 These disparities reveal the lack of an efficient and consistent performance management system that shapes adequate incentives for equivalent SOEs.

Finally, all SOEs benefit from access to state financial resources. Depending on the industry, the demand for state budget funds may vary from an SOE to an SOE. For instance, SOEs operating in the military sector rely significantly on the State as the primary investor and consumer, while publicly-listed SOEs operating in revenue-generating sectors such as oil and gas tend to depend less on state budget funds. Nonetheless, even the most profitable SOEs take advantage of soft budget constraints and existing federal programs to compensate for their costs.Footnote 165

The next question is the extent to which Russia's state ownership system is similar to or different from other models. The literature draws on several well-studied examples of state-driven economic systems, including Brazil, India, and China.Footnote 166 However, Russia's leadership might favour China's experience the most for the following reasons. In recent years, China-Russia relations have attained an ‘unprecedentedly high level’.Footnote 167 The leadership of the two States praises the comprehensive and strategic partnership and display of closeness of their cooperation.Footnote 168 In 2015, Russia and China signed a joint statement on cooperation between the Belt and Road Initiative and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU).Footnote 169 The two countries embrace the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), of which both States are active members. The ties between Moscow and Beijing have entered new frontiers amid their deteriorating relations with the West. Western sanctions accelerated and expanded Sino-Russian cooperation boosting new technology, manufacturing, and military projects.Footnote 170 Beijing and Moscow refer to each other as ‘priority partners’ that seek to strengthen political, security, military, economic, and energy cooperation.Footnote 171 For Russia, its pivot to the East is a natural response to the pressure from the West. Moscow is Beijing's largest arms supplier, while China is Russia's top trading partner.Footnote 172 In 2020, bilateral trade reached US$107 billion, representing a dramatic increase from US$58 billion in 2010.Footnote 173 Russia is China's second-highest provider of oil, after Saudi Arabia.Footnote 174 Russia actively attracts Chinese investments in its financial market, energy sector, and infrastructure, while China is interested in building its presence in Eurasia to create economic and transport links between Asia and Europe. These mutual economic interests supported by like-minded political regimes and foreign policy alignment make Chinese SOEs the most appropriate example for comparative analysis.

The comparative analysis of Russia's and China's state ownership systems exposes several main similarities and differences, particularly relevant to this study. Large SOEs play a central role in the strategic sectors of both countries. They dominate their industries domestically and are increasingly active globally.Footnote 175 The analysis of state ownership in China emphasises its main flaw: the lack of autonomy and profit incentives.Footnote 176 Similar to Russia, corporate boards in China's SOEs are primarily selected through political and administrative processes rather than endogenously chosen in the competitive managerial market.Footnote 177 Like China, Russia employs ‘a networked hierarchy’ of a group structure to manage its SOEs.Footnote 178

Unlike China, though, Russia's system is decentralised, with several ‘core’ organisations controlling groups of SOEs. Although these groups can be vertically integrated, not every group is concentrated around a particular production chain or sector. Instead, they might be highly diversified across a wide range of industries. They combine hierarchical shareholding with cross-ownership. Therefore, Russia's system appears to be even more complex, representing a hybrid between China's hierarchical architecture and the Japanese keiretsu or the Korean chaebol.Footnote 179

Another difference relates to the parent company at the top of each group. In China, these companies typically are former ministries transformed into corporate entities. In Russia, state corporations are not corporate entities, but non-commercial organisations with all the peculiarities discussed previously. State corporations report directly to the Federal Government and the Presidential Administration. They do not serve as an intermediary between the state agency and the group. Instead, they fulfil the state shareholder's role, act as asset management companies, and produce policies and regulations. Although multiple actors can complicate or obstruct the coordination process, Russia's leadership prefers a multipolar system that identifies no single powerful agency managing huge state assets and potentially questioning the leadership's agenda.

In contrast to the Russian approach, China has demonstrated a firm commitment to the strongly recommended corporatisation.Footnote 180 Driven by much greater global market and trade exposure than Russia, the Chinese leadership has been pragmatic in its desire to improve management and performance by corporatising its SOEs and adopting market principles.Footnote 181 Many SOEs in China have been converted from political entities to market-oriented corporations that operate internationally and compete globally. Chinese large SOEs are widely represented in the Fortune Global 500.Footnote 182 China's Company Law applies to all enterprises, including corporate SOEs.

Finally, the Chinese Communist Party exercises significant influence over corporate governance and decisions in strategic SOEs.Footnote 183 China's system has two parallel structures: a traditional corporate shareholding structure and a party-based political structure.Footnote 184 This duality is embedded in the corporate governance of China's SOEs making it unique and context-specific.Footnote 185 In Russia's case, there is no political party element in SOE governance. The ruling party United Russia neither possesses the same extent of influence on the management of Russia's SOEs nor serves as an institutional bridge that connects the system's elements as in China's case.Footnote 186

Conclusion

This article examined the role of law and corporate governance in enabling the growing influence of the state in Russia. The analysis sheds light on the organisational framework of SOEs, their objectives, and governance mechanisms. Despite increasing scholarly attention to legal institutions and governance practices of state capitalism, existing studies have focused primarily on Asian economies, while Russian SOEs remain lost. In Russia, the Federal Government has chosen to set up a group of new SOEs and deal with unexpected contingencies through their internal governance structures rather than establishing a contract-based regulatory regime to address such concerns.

The newly established SOEs are non-corporations from the perspective of both Russia's civil law and the scholarly understanding of a corporate entity. Russia's SOEs add another perspective to the understanding of state ownership systems and corporate governance narratives. In this context, the current recommendations and standards offered to SOEs may provide limited insight into Russia's state ownership system. Recent economic challenges and political agenda have shaped the Federal Government's response that provides the State with full discretion and control over its SOEs. The law expressly channels policy mandates from the Federal Government, eliminating any ambiguity about SOE objectives and awarding the state owner with substantial power over SOEs’ governance. This approach has its own costs, including unequal treatment of legal entities and the lack of solid and comprehensive regulation.

While Russian markets continue to be affected by limited access to capital, imposed sanctions, and countersanctions, the Russian economy proceeds with the reliance on the state sector, which will be driven by the Federal Government strategies and Russia's national interests. These strategies bring about legislative changes and state ownership policies that can drive the system even further away from contemporary governance standards. The State's controlling position continues to be a significant factor in determining accountability structures and investment policies in Russia. Many SOEs operate not as independent corporate entities but as an instrument of the state policy that manages a large market-oriented portfolio. Without acknowledging this context and the actual dynamics of Russia's state ownership system, the dominant academic view on SOE governance sheds little light on SOEs in Russia. It can even be misleading in terms of Russia's political, legal, and economic landscape. Unless this context is understood, attempting to draw a simple analogy between corporate governance theories and Russian SOEs will most likely obscure rather than illuminate the nature, features, and impact of Russia's SOEs. This gap calls for further studies of performance, governance mechanisms, and the political economy of SOEs in Russia and their comparative analysis with other state-driven models.