The DataBase for Applied, Fine and Performing Arts (AFPA-DB) results from a growing need at art universities to provide access to artistic research (AR) as both:

a) a source and reference for research and education; and

b) in terms of publication: presenting and situating one's own research results in a larger academic environment.

While an overview of options for publishing art and design has been published as the first outcome of our research (Lurk Reference Lurk2021), this text focusses on the side effects of data collection.

In 30 September 2021, 1035 entries from 38 international universities (including 28 of the 44 German-speaking art academies)Footnote 1, 3 AR associationsFootnote 2, and other individual entries were indexed in the AFPA-DB. Included were 183 monographs, 112 book contributions, 243 journal articles (including 154 contributions from the Journal for Artistic Research), 2 conference papers, 34 artworks, 7 blog posts, 32 documentaries, 2 films, 34 presentations, 22 reports, 94 student theses and dissertations (including 47 dissertations from German-language art schools), 17 video documentaries and 253 websites (including 108 entries from the international exchange programme Atelier Mondial).Footnote 3

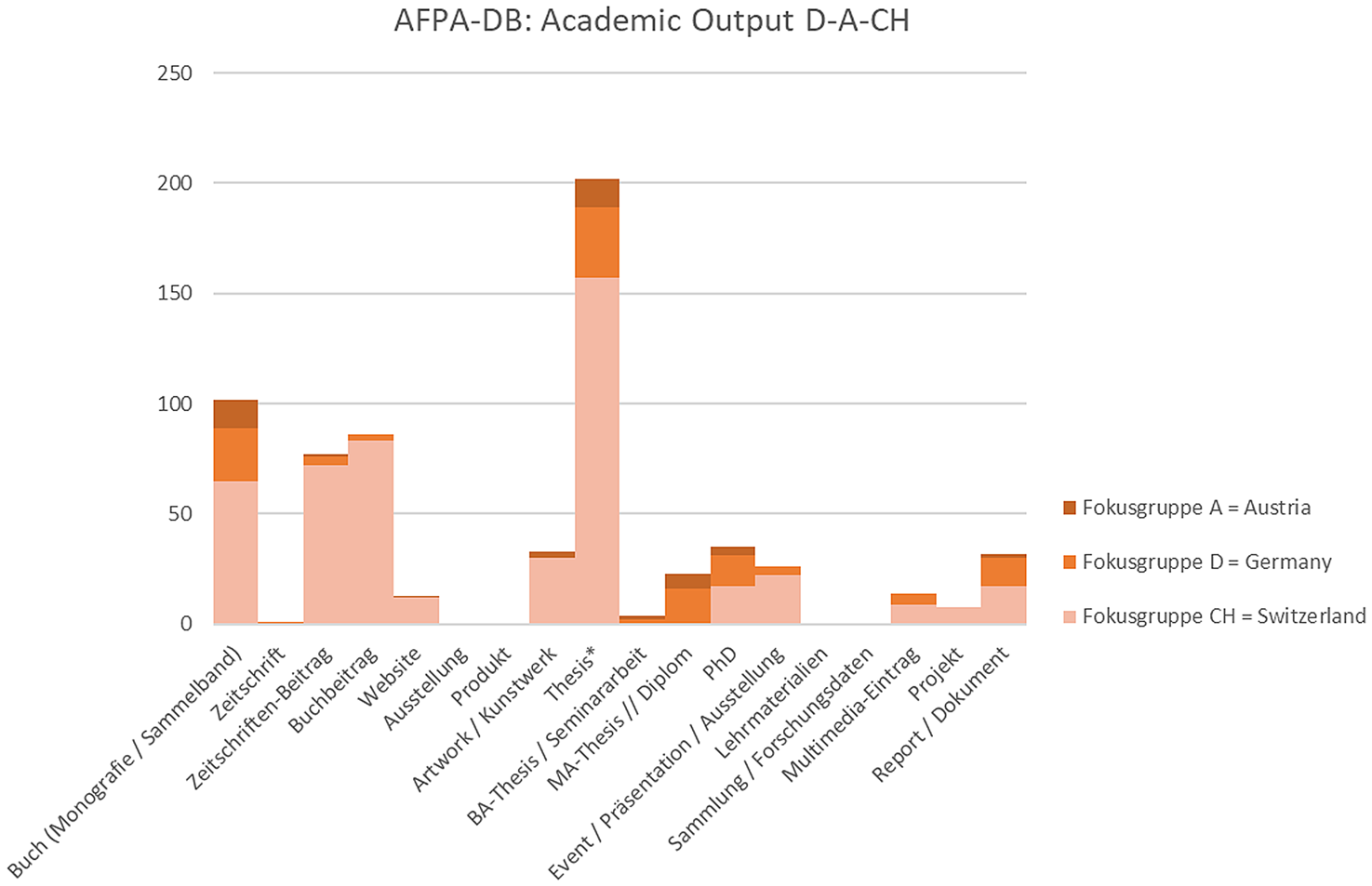

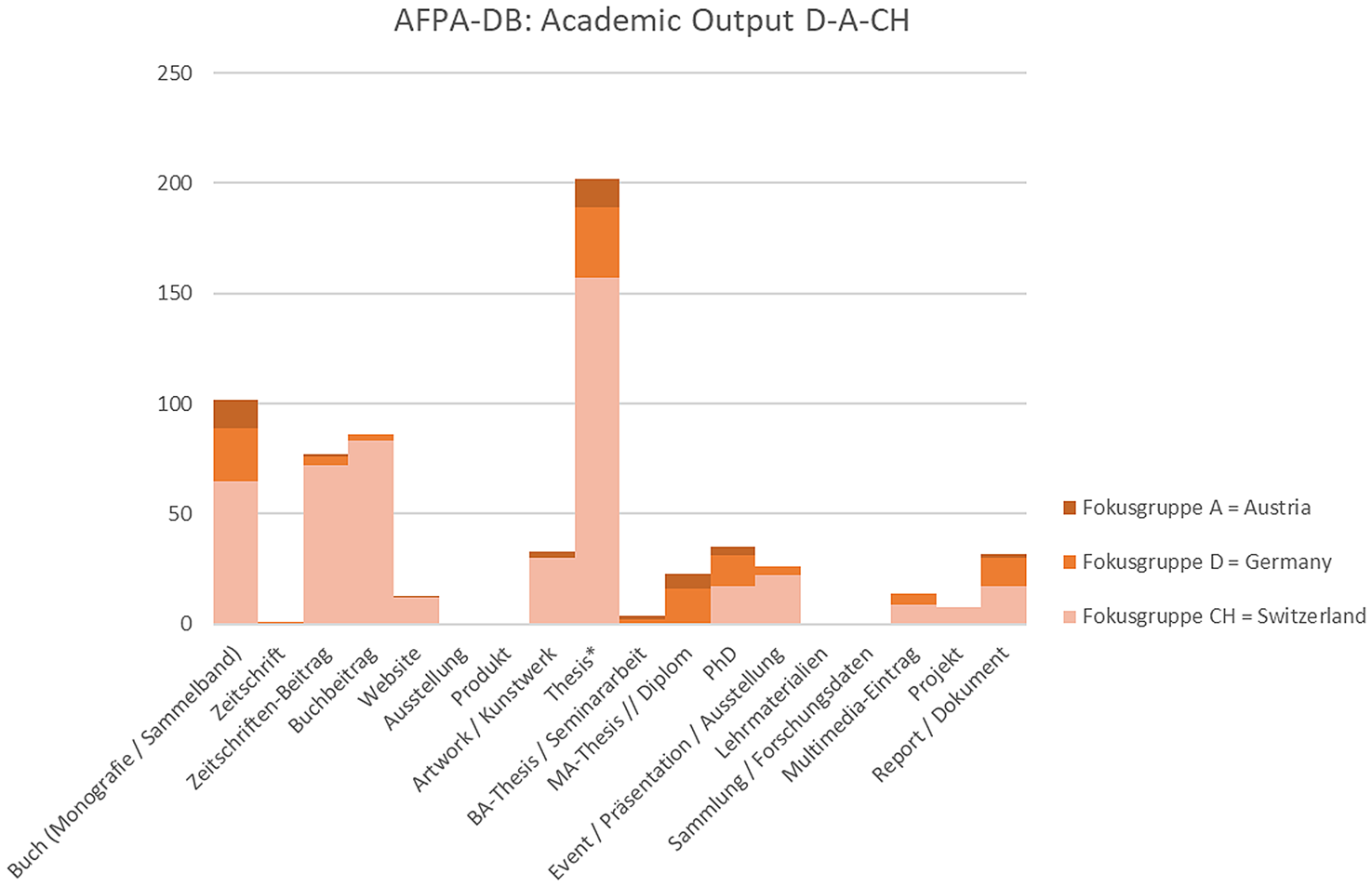

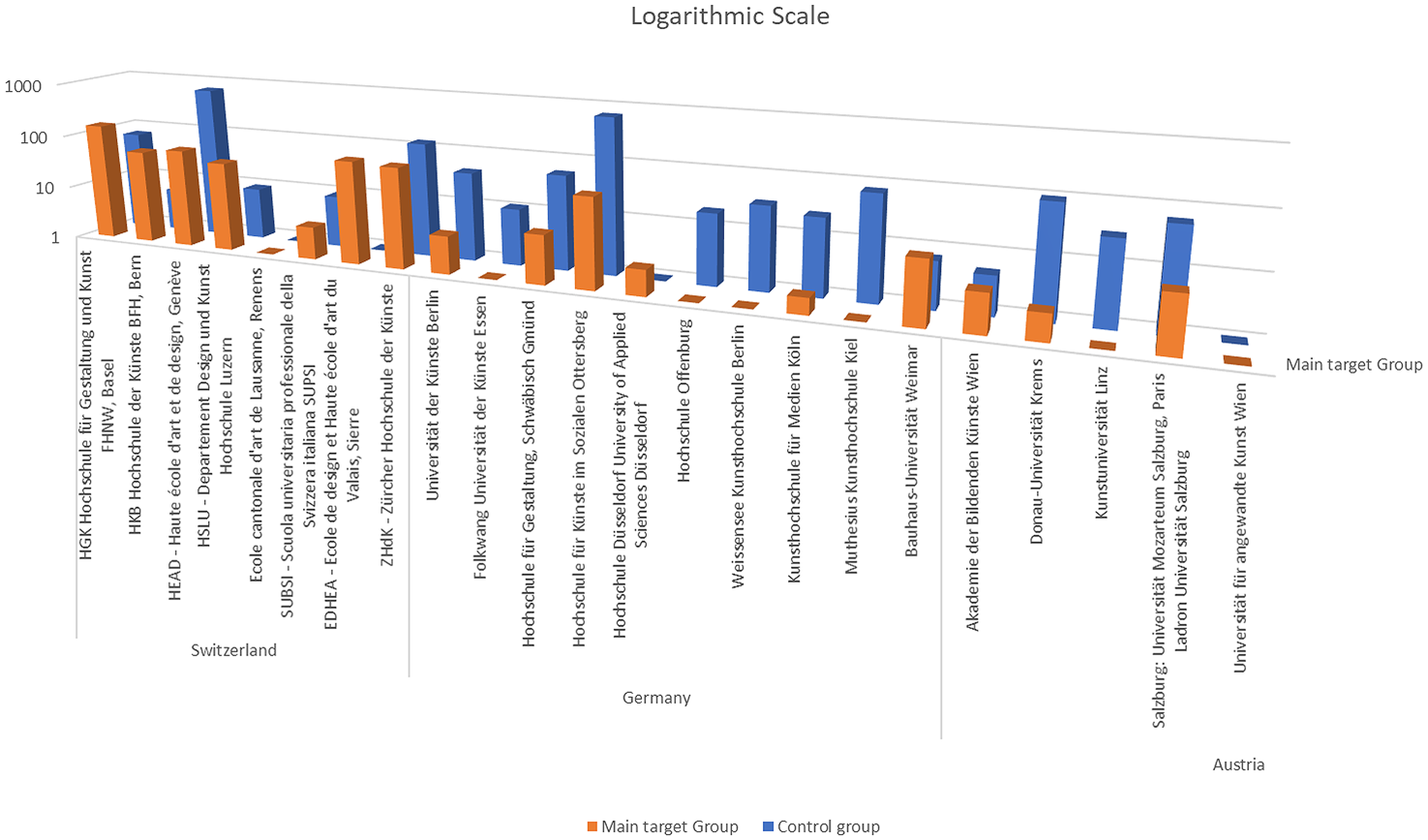

In August 2021, the AFPA-DB results from the 28 art academies in Switzerland, Austria, and Germany were analysed. Even though the results are too heterogeneous for comparisons, the collected entries were counted and listed according to document types. Furthermore, a control group was then created, in which only the results of a keyword search within the respective repositories/publication servers was counted. Beyond semantic differences, since the difference between AR outputs and AR reflection was ignored, the institutional websites were left out of the control group (but were, however, included in the AFPA-group).

The following considerations result from an analytical reflection on metadata information that was captured during the research and collection phase, focussing on: a) the location where the entry was found; b) accessibility, including copyright information; and c) keywords (or lack of keywords) used for description. After a brief outline of the motivation, the text discusses the effects of systemic weaknesses which became apparent during the research. In doing so, we look for reasons why the results of AR are so difficult to find.

Fig. 1. Overview of the total number of entries, according to document type, sorted by country (German-speaking countries). Since educational resources and (research) data packages occurred only in the control group, the bars are empty here.

Fig. 2. Overview of the total number of entries (regardless of document type) sorted by academy/country. While the orange bars show the AFPA-DB entries, the sum of the hits of the respective control group is coloured blue.

Need for study objects

In the specific context of art academies, artistic or creative works have always been both objects of studyFootnote 4 and resultsFootnote 5. Although art – at least art since the 1960s – has established its own genres of becoming public, discursive, or engaging in open dialogue with dedicated audiences, traditional scientific modes of communication, which increase especially with the research requirements of AR, still seem challenging. Thus, the artistic researcher continually discusses the “transposition”Footnote 6 between artistic modes of approaching the public within the (art-)work and publication standards in the scientific community.

For the last 20 to 30 years, AR has become a topic of scientific funding, accreditation and evaluation procedures, including discussion on publicationFootnote 7, evaluationFootnote 8, and methodologiesFootnote 9. Concerning the performance measurement of artistic “outputs”, the Swedish model seems groundbreaking.Footnote 10 For staffing procedures, Lilja has proposed a question grid, and further considerations regarding assessment or quality management procedures can be found in different contexts.Footnote 11 While on one hand, the ongoing debate and (self-)questioning of artistic researchers leads to fruitful results, which continuously expand the discipline,Footnote 12 on the other hand the integration of AR approaches as a critical or methodological framework for teachingFootnote 13 demonstrates how established the field has become – even in traditional subject areas such as painting.Footnote 14

Nevertheless, the fractures still existing between art and academia lead to various daily challenges for art libraries.Footnote 15 Starting with the questions of access (acquisition and information retrieval), continuing with publication and data management support (including rights issues), up to an increasing institutional interest in the bibliometric measurement of art and science, one can find seemingly endless construction sites. At the same time, all have a common interest in locating AR. This leads to a simple (starting) question: Where is AR – or rather: How can AR results and outcomes be located?

Searching for Artistic Research

The systematic search for AR on academic platforms such as Web of Science, Scopus, JSTOR and Design & Applied Arts Index (DAAI) results in a considerable number of findings. Nevertheless, most entries discuss or write about AR rather than being the results of AR in the sense that Borgdorff explained when stating:

We can justifiably speak of artistic research (‘research in the arts’), when that artistic practice is not only the result of the research, but also its methodological vehicle, when the research unfolds ‘in and through’ the acts of creating and performing.Footnote 16

The cited comment explains, among other things, why for example (digital) humanities repositories, publication services and research portals only partially cover the professional needs of art and design.Footnote 17 Even though they are located in the same cultural environment as creative, practice-based/practice-led approaches, there are fundamental differences in:

a) the way the research is conducted (including the definition of aims, the setting of methods and the prospecting for interim results);

b) the way that outcomes and publications appear in a variety of formats; and

c) the technical needs for describing, characterizing, or classifying.Footnote 18

Narrowing down the previously mentioned search results using classic research routines such as keywords, filtering dedicated media or document types, or other formal (metadata) characteristics is problematic in that conventions do not exist for this, nor are there preferred or standardized subject terms, publication formats or source-types. Of course, there is a Gemeinsame Normdatei (GND) entry for AR,Footnote 19 but finding or rather offering controlled vocabularies and classifications for dedicated subject areas in AR seems extremely difficult. Whereas on the one hand the lack of vocabularies or classification systems is problematic,Footnote 20 on the other hand the heterogeneity of the topics and methodologies, the creativity of the artists in questioning and (re-)inventing everything, and a certain scepticism complicate finding solutions.Footnote 21

In fact, the discomfort of the researching artists often begins earlier – within the publication or indexing process: object types used by repositories or publication servers such as OPUS, DSpace, Fedora and Zenodo, as well as those of the web portals mentioned, seem rather coarse compared to the diversity of artistic ways of expression and becoming public. Of course, Resource Description and Access (RDA) and most academic bibliographic systems in general offer a remarkable variety of media formats, while DataCite Footnote 22 and the Confederation of Open Access Repositories (COAR 2021) provide a remarkable list of resource type vocabularies. Nevertheless, the implementation is often pending. Thus, classifying artistic outcome remains demanding. In addition, Veerle Spronck points out:

The artistic researchers have to deal with art worlds (consisting of art critics, curators and festival organisers as well as the general art public), academic communities, and in some cases they contribute to public debates. To make the outcomes of their research relevant and assessable to these diverse audiences and communities, work needs to be done.Footnote 23

Classifying art in a publication context

Understanding Efva Lilja'sFootnote 24 recent statement “[t]he object of artistic research is art”Footnote 25 as a serious hint, another type of cataloguing system that has largely been neglected so far might come to mind: collection management systems.Footnote 26 Whereas Lilja's activating essay points to the risk of losing meaning or relevance when adapting (appropriating) scientific attitudes from other contexts too ambitiously, one might indeed ask how far scholarly communication could benefit from the ways of describing and documenting art.Footnote 27

Collection management systems specialize in taking the significance (individuality) of an artwork into account. While conservation science tends to speak of “significant properties”, when works of art become more complex, semantically breaking down “the” work of art to a set of elements which might be preserved in different ways, and looking at materials and techniques (as ways of creation) can enrich the present discussion. With regard to AR outcomes, methodologies gain special importance. As Rachel Mader explains, when reflecting on Brad Haseman's concept of practice as research approaches to creative arts enquiry: “research is not only conducted to create content, but also to expand the methods and instruments of artistic practices in each single case”.Footnote 28 Thus, AR methodologies might be understood as a natural progression of the material and techniques approach.

Expanding the forms of describing varying ways of creating, exploring, producing, and presenting, and the emphasis of methodologies calls to mind more recent developments in the context of scientific publishing as offered by data journals or data publications. Here, as there, the description of both the procedures of data collection and research methods, and the way in which the data was then structured and evaluated, contribute to the later understanding and subsequent re-use. Dedicated areas are therefore provided by the respective infrastructures. Relational models have replaced field-based indexing forms. Accordingly, a look at schemas such as CIDOC CRM from the cultural heritage perspective or Records in Context (RIC) from archival practice might be worthwhile. They stay structurally flexible and extendible, and therefore support creativity and liveness. Furthermore, conceptual models for describing such as the standard for open educational resources (IEEE Reference Lurk2020), would have to be examined. LOM's (Learning Object Metadata) capacity to address different target groups even at the metadata level seems extremely interesting.

Nevertheless, our aim is not to promote yet another standard that is not applied because it is too complex or specific or fails to gain acceptance due to other reasons. Quite the opposite: we have the feeling that the initial question of the availability or rather the findability of AR results relates to further structural problems.

Referencing AR as research outcome

Starting, for example, with a well-established, scientific practice such as the referencing of sources of literature, data, tables, graphs, etc. used in articles and papers, it seems clear that citation conventions are so well established that algorithms automatically recognize most quoted sources. Automatic reference detection is, among other things, the basis for quotation indices.Footnote 29

As opposed to literature, artworks and AR outputs often elude citation. Even if works of art are named within a text, the automated detection of their mentions normally fails due to missing or incomplete structuring conventions. While lists of illustrations sometimes present a specific kind of index within the text, they nevertheless seem so little standardised that automated counts with an accuracy equivalent to Hirsch-Index or Received Citations are not yet available. This affects virtually all the artistic formats, including musical or performative scores, theatre plays and photographs that are not dealt with by well-known publishers - even if a catalogue raisonné exists with established numbering.Footnote 30

On the one hand this ties in with considerations in the museum context, in which referencing, the preservation of context and/or the quality assurance of online (re-)sources are discussed.Footnote 31 On the other hand, collaboratively created meta-searches such as European-art.net (EAN) are gaining importance.Footnote 32 Initiated by Basis Wien and resulting from the EU funded vektor (2000-2003) project, EAN references not only artists,Footnote 33 exhibitions and publications of the 13 partner institutions, but also enables searching for artworks, if the source databases release this information. To what extent the trend towards the visualization of collection holdings, as found in the context of Linked Open Data, Knowledge Graphs, various other data models and as countless pilot projects, is relevant for the present context of referencing remains to be examined.

Easy ways out of the dilemma are not to be expected in the short term, for the following reasons:

a) AR outcomes are spread across different genres (from dedicated works of art to curatorial work, from publication to performance, etc.) and artists tend to engage in different formats;

b) publication venues and institutional framings seem constantly changing, from academic context via gallery and museums spaces to public or alternative sphere(s), including digital and hybrid environments; and

c) communication channels often cover only temporary needs and disappear or migrate sooner or later to other media.

Furthermore, artistic outcomes, and especially those of AR, are bound to the presence of the audience. With Andrea Phillips one can state:

The claim of artistic research is that it is radically open and thus accessible to all comers, giving rise to questions of explanation, exposition, methodological investigation and publishing itself (in the sense of ‘making public’), especially in a field dominated by privatization (both in terms of art's connection to infrastructures of its market and in terms of the pedagogical habitus of individuation of expression).Footnote 34

Free and Open Access

The statement highlights another conflict zone that becomes obvious when publishing: the basic understanding of openness in relation to access. While the Budapest (2002) and Berlin Declaration (2003) define – from a libraries perspective – what Open Access (OA) is and how it should be marked, for many artists and researchers in this field, content that can be “consumed” without login, payment or admission is considered open and accessible. Therefore, just under 12% of the current AFPA-DB entries can effectively be described as OA, even though almost 28% are accessible without restrictions (bronze OA). Some faculties still believe that a sentence such as “[title] is accessible online to all (Open Access)” and the provision of a digital resource (PDF, image, video) make the publication OA. Expectations clash with reality when informing them that OA requires a clear statement for reuse, indicated for example by adding a creative commons statement and holding a signed contract note in hand (or in the archive). Accordingly, Clarrie Bishop has pointed out that successful OA projects are “about placing relationships at the heart of your work and thinking about rights collectively”.Footnote 35

Leaving aside “things” that are also traded on the art market,Footnote 36 and focussing instead on AR results and their context, OA currently gains increasing importance. In a cultural framework of inequality, in which many artists are still seeking a voice, permanent identifiers and the commons play a special role. They bring reliability, traceability, and permanence to a digital environment that otherwise seems highly dynamic and unstable. As Henk Borgdorff stated, when weighing the advantages and disadvantages of AR in relation to increasingly easier accessible scientific infrastructures:

You gain stability and the potential for distribution at the cost of the singularity and materiality of the operator. In artistic research this involves the chain of reference between artwork at the one extreme and artistic research publication at the other.Footnote 37

To put it differently: OA does not require reluctant relabelling, accepting reduced quality caused for example by low image resolution or black and white printing. Rather, the fracturing of incompatible legal systems creates space for new creativity, as encountered in different publishing contexts.Footnote 38 In a constructive, solution-oriented environment, it is then also possible to think carefully about what re-use can mean in the context of design and art.

Conclusion

AR seems to be a topic that is discussed at virtually all art academies. Nevertheless, when browsing the related scientific infrastructures, significant, partly structural, differences occur: while some art academies have developed digital memory infrastructures, others are still waiting for publication servers, repositories, or (supra-)institutional access. Differences determine the field in other contexts as well, for example financial and human resources, time span since resources were systematically documented, acquisition/indexing and publication policies, the question of how or where closed content is accessible (as metadata and data), accepted file-formats, evaluation mechanisms, and/or workflows and instruments for quality approval. Certainly, the size of the institution (measured by the number of staff and students), subject orientation (type of specializations), and structural scopes of action vary.Footnote 39

Since only parts of the AR outcomes find their way into the available repositories, the websites of the research institutes and their projects, associated PhD programmes and fellowships play a special role regarding AR dissemination. Even if neither plain HTML-websites nor portals with structured content management systems facilitate scholarly communication in terms of publication, access, and reuse (at least from a library perspective), these network-based channels still seem more easily equipped by artist researchers and thus more accessible than repositories or publication servers.Footnote 40 In addition, dedicated blogs, social media platforms and multimedia networks would require further consideration.Footnote 41

Regardless of the popularity of repositories among the artistic researchers, the lack of appropriate forms of citation and referencing has emerged as a particularly problematic area. The topic goes beyond the AR community and requires other disciplines to take responsibility for their sources. Whereas AR outcomes are indeed widely dispersed and hard to track, and thus tend to get lost in the plethora of activities, lack of global directories and referencing standards also cause problems.

Nonetheless, OA has emerged as an element that constructively stimulates the dialogue between libraries, artistic researchers, and, ever more frequently, non-affiliated artists or communities who can contribute to the discussion or provision of sources. Increasing interest in collaborative, sustainable, and resource-saving practices as well as manifold forms of access, accelerate the ways of knowledge production and consumption.Footnote 42 The tangible culture of cooperation and the claim to exchange ideas at eye level can contribute to the overcoming of existing divides. This can contribute to better accessibility of AR, too.