Introduction

The disposal of corpses through means that leave little or no archaeological trace is recognised as a component of mortuary pathways in Iron Age Britain (e.g. Carr & Knüsel Reference Carr, Knüsel, Gwilt and Haselgrove1997; Harding Reference Harding2016; Armit Reference Armit, Bradbury and Scarre2017; Legge Reference Legge2022). For the Roman period, a comprehensive survey of material evidence has recently shown that formal burial remained rare away from urban areas: the rural population never substantially adopted the urban custom of gathering the dead in cemeteries, but instead maintained largely invisible funerary rites (Smith Reference Smith, Bradbury and Scarre2017; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Allen, Brindle, Fulford, Lodwick and Rohnbogner2018: 275–77).

In this article, we make the case that the treatment of the dead without burial persisted beyond the end of the Roman period in Britain, into the fifth century AD and beyond, and that this has critical implications for our understanding of cultural developments in lowland England in particular. A scarcity of mortuary material from the fifth century AD, especially its first half, has long been noted in areas of eastern and southern England. Here, we bring together new strands of evidence to argue that this low level of visible burials should be explained, at least in part, in the same way as the under-representation of Romano-British rural funerary remains: formal burial was not a predominant rite.

Although non-burial disposal is intrinsically hard to see archaeologically, it may be glimpsed in the Iron Age and Roman period in finds of disarticulated skeletal remains outside of formal cemeteries. We present a review of radiocarbon-dated material from riverine and cave contexts in England and Wales showing that alternative forms of disposal of the dead continued into the early medieval period.

Lasting non-burial funerary customs have significant implications for understanding the transition from the Roman to the early medieval period in lowland England. Until now, persistence of Roman-period mortuary practices, and thus continuity of population, have been sought only in formal burials (Lucy Reference Lucy2000: 170–73). By contrast, we show that the older, non-burial funerary rites fall outside current frameworks for interrogating the changes seen in the archaeological record.

The missing dead of the fifth century

The fifth century AD is a period of significant cultural change in the archaeological and historical record of lowland Britain. By the time of the Roman withdrawal, usually dated to AD 410, southern and eastern England had already seen the Romano-British way of life decline. A significant drop in population is likely, although debated. Palaeoenvironmental evidence suggests that some regions remained intensively occupied (Rippon et al. Reference Rippon, Smart and Pears2015), with recent work tending to emphasise that elements of Roman-period culture were maintained longer than was once thought (e.g. Dark Reference Dark2002: 97–103; Hinton Reference Hinton2005: 7–38; Fleming Reference Fleming2021: 60).

New forms of material culture appeared, most distinctively in the establishment of rural cemeteries made up of furnished cremations and inhumations. Both the rituals and the artefacts seen in these show associations with regions across the North Sea and have traditionally been explained by the ‘Adventus Saxonum’—the arrival of the Angles, Saxons and Jutes in the mid-fifth century—as described in written sources; the nature and extent of this settlement is one of the most heated debates in British archaeology (e.g. Dark Reference Dark2002; Hills Reference Hills2003; Oosthuizen Reference Oosthuizen2019; Harland Reference Harland2021). Much discussion focuses on the dead in the new cemeteries and to what degree they represent new and intrusive populations, based on artefactual, ritual, isotopic and ancient DNA evidence (e.g. Lucy Reference Lucy2000; Gretzinger et al. Reference Gretzinger2022; Leggett et al. Reference Leggett, Hakenbeck and O'Connell2022). Both isotopes and ancient DNA indicate considerable mobility within and into lowland England in the early medieval period, consistent with high individual and small group mobility seen across Europe at this time (Depaermentier Reference Depaermentier2023).

Two underlying problems in the mortuary record hamper these discussions. First, although the novel burial and artefactual forms that appear in the fifth century can readily be compared with examples from the northern continent, it has proved harder to compare them with local graves from the preceding centuries. For example, Spong Hill in Norfolk, a cremation cemetery with over 2300 graves, demonstrates material culture connections to several regions on the other side of the North Sea from the first quarter of the fifth century. Yet, despite the density of recorded Roman-period settlements, rural burial evidence—against which the early medieval material can be placed—has proved sparse, with only some 245 burials dating to the Roman period excavated in Norfolk by 2013 (Hills & Lucy Reference Hills and Lucy2013: 297–331).

A strong contrast is often drawn between the new funerary forms of the fifth century and late Roman customs typified by unfurnished inhumations with uniform orientation in large, managed cemeteries. This distinction depends on a limited number of mainly urban cemetery excavations around Romano-British towns, whereas late Roman rural burials display a great deal of diversity, with much variation in burial positioning and orientation, use of grave-goods and occasionally cremation (Smith Reference Smith, Bradbury and Scarre2017). More than that, a key conclusion from work in the last few years mapping mortuary activity in the Romano-British countryside is that a substantial component of these activities remained archaeologically invisible (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Allen, Brindle, Fulford, Lodwick and Rohnbogner2018: 275–77). Late Roman funerary finds are in short supply for comparison with fifth-century remains because burial was not the normative rural rite.

The second difficulty is that the new material forms, despite their importance as new cultural introductions, are seen at markedly low levels before the sixth century. Robin Fleming (Reference Fleming2021: 180) has recently drawn attention to how little Anglo-Saxon-style pottery and metalwork dates to the fifth century. The number of graves providing a window directly on the fifth century are also low; just one individual out of nearly 500 and 20 out of 2000 in recent syntheses of ancient DNA and isotopic data, respectively, could be definitively dated to the fifth century (Leggett et al. Reference Leggett, Rose, Praet and Le Roux2021; Gretzinger et al. Reference Gretzinger2022). Large fifth-century cremation cemeteries along the lines of Spong Hill are concentrated in an area around the Wash, in Norfolk and Lincolnshire, with just under a dozen examples (Hills & Lucy Reference Hills and Lucy2013: 335–39). The contributing population for the fifth-century phase at Spong Hill is estimated at 826 (Hills & Lucy Reference Hills and Lucy2013: 294), and although the records of the other cemeteries are limited, most are smaller. Mucking, near the Thames in Essex, is an outlying early site, with cremation burial thought to have started in the early fifth century (Hirst & Clark Reference Hirst and Clark2009: 626).

Elsewhere in lowland England the mortuary record for the century, especially its first half, is much more limited. In the county of Kent, for example, the dearth of fifth-century burials led to a suggestion that the first post-Roman settlers practised cremation and that their graves have been destroyed by subsequent ploughing, although this is unlikely as cremations from other periods survive (Richardson Reference Richardson2005: 91). In a comprehensive analysis of early medieval mortuary material from the county, Andrew Richardson (Reference Richardson2005: 64) could list just 38 locations of either fifth-century graves or material likely to come from them. Finds from early in the century appear to be isolated and include a weapon burial from the Roman fort at Richborough and a pit in the Roman town of Canterbury containing four human bodies and a dog (Bennett Reference Bennett1980). Formal cemeteries date from the mid- and later fifth century, with the cremation cemetery at Ringlemere one of the earliest (Marzinzik Reference Marzinzik, Brookes, Harrington and Reynolds2011), although the first grave at Lyminge might be as early as AD 425. Only about 20 of the approximately 120 known fifth- to seventh-century burial places in Kent include graves that date (or possibly date) to the fifth century and almost all of these are from the later decades (Richardson Reference Richardson2005: 64).

Current chronologies probably miss some material that belongs in the fifth century, especially its first half. James Gerrard (Reference Gerrard2015) has argued that some burials assigned to the late Roman period could be placed in the fifth or even sixth centuries. A plateau in the radiocarbon calibration curve can make the fifth century difficult to distinguish from the early sixth century (Hines & Bayliss Reference Hines and Bayliss2013: 35–37). Conversely some novel material may be placed too late: in England, as in other areas of Europe (e.g. Koncz Reference Koncz2015), historical dates have directed archaeological dating, so that material thought to indicate ‘Germanic’ arrivals has often been assigned to after the mid-fifth century. The publication of Spong Hill (Hills & Lucy Reference Hills and Lucy2013) shows decisively that new burial and artefactual forms may date several decades earlier. Re-dating of specific sites—for example, two close-lying, Roman-style and early medieval cemeteries in Oxfordshire at Berinsfield and Queenford Farm (Hills & O'Connell Reference Hills and O'Connell2009)—has raised the possibility that some early medieval artefact chronologies from inhumation graves may also begin earlier in the fifth century, and thus that the new style of cemetery may immediately succeed the old. At Wasperton in Warwickshire, six cremations initially thought to be late fifth or sixth century were radiocarbon dated to the fifth century and possibly earlier (Carver et al. Reference Carver, Hills and Scheschewitz2009: 49, 90); there may also be a phase of fifth-century unfurnished inhumation at the site (Carver et al. Reference Carver, Hills and Scheschewitz2009: 92, 122). Similarly, there are hints from areas of the continent where fifth-century sites are also under-represented, that some unfurnished graves may date to this phase (e.g. Sebrich Reference Sebrich2019). The fifth century in Wales, meanwhile, is poorly understood due to poor bone preservation and a tendency towards unfurnished burials, which hampers dating (Edwards Reference Edwards2023: 3).

Nevertheless, the overwhelming scarcity of fifth-century finds becomes only more evident as growing numbers of regional overviews and databases are delivered. A recent landscape study of Essex showed only a handful of burial sites that could be placed in the fifth century, mostly single graves or small groups (Rippon Reference Rippon2022). Known cemeteries from this time are found exclusively on the coast or along major rivers, yet palaeoenvironmental data and place-name evidence shows that inland regions were inhabited (Rippon Reference Rippon2022: 25). An argument is made for two distinct populations: an incoming group who settled primarily on the coast, and a Romano-British population who continued to cultivate inland. Yet where are the dead of that inland group?

Alternative mortuary pathways in first millennium Europe

For the Romano-British period, the thousands of graves around towns have tended to draw attention away from the scarcity of contemporaneous rural burials. A decade ago, John Pearce (Reference Pearce2013: 25) quantified the problem, calculating that the ratio of excavated burials to the predicted original burial population was over forty times lower in rural than urban areas. He suggested that ‘invisible’ funerary traditions, well-known from the Iron Age, probably continued into the Roman period. Collation of evidence from Romano-British rural contexts indicates the persistence of this lack of formal interment across the majority of England and Wales, even within the Romanised heartland of south-east England (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Allen, Brindle, Fulford, Lodwick and Rohnbogner2018). Burying the dead in graves, whether cremated or unburnt, appears to have been part of the cultural shift of moving into towns, rather than a custom adopted across the population.

Iron Age non-burial traditions are thus argued to have persisted in rural mortuary pathways through to at least the end of the Roman period (Smith Reference Smith, Bradbury and Scarre2017; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Allen, Brindle, Fulford, Lodwick and Rohnbogner2018: 275–77). Current evidence points to a variety of practices for the treatment of human remains in prehistory, including sheltered exposure, primary burial and exhumation, and various further processing, use and sometimes careful deposition of bone (e.g. Booth & Madgwick Reference Booth and Madgwick2016; Armit Reference Armit, Bradbury and Scarre2017; Brück & Booth Reference Brück and Booth2022; Legge Reference Legge2022). Activities are witnessed through finds of disarticulated skeletal parts, discarded or deposited in a range of contexts all over Britain (Armit Reference Armit, Bradbury and Scarre2017: 162). Such finds are now known to continue through the Roman period, with disarticulated human remains recorded at 462 rural Roman sites. Almost half of these places were farmsteads, and at 30 per cent of these, there was no formal burial at all (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Allen, Brindle, Fulford, Lodwick and Rohnbogner2018: 277). Further examples of non-burial treatment are coming to light now that alternative funerary practices are an increasingly accepted possibility (Buck et al. Reference Buck, Greene, Meyer, Barlow and Graham2019).

Turning to the early medieval period, it has long been observed that the buried dead do not fully represent the living population, even in the well-documented furnished cemeteries in sixth- and seventh-century lowland England. The numbers of infants and children in particular are far too low (e.g. Crawford Reference Crawford1999: 24–25). Newborns are occasionally found in settlement contexts, but not in large enough numbers to account for the missing infants (Sofield Reference Sofield2015: 369, 378). Sally Crawford (Reference Crawford1999: 24, 76) therefore suggests that “dead children may have been disposed of in other ways”, perhaps including cremation without subsequent burial. Other demographic imbalances have also been noted (e.g. Hines Reference Hines, Lucy and Reynolds2002), as has the idea that those formally buried may have been a specific subset of the population (Carver Reference Carver2019: 347). It is thus likely, and by no means a new suggestion, that even communities who established and maintained cemeteries also practised alternative forms of mortuary disposal.

Yet awareness of the likelihood of non-burial rites in the Early Middle Ages has not translated into further investigation of possible clues about the nature of these rites, nor the tracing of their presence back in time. In research from all periods, the unburied dead are typically sidelined (Weiss-Krejci Reference Weiss-Krejci, Tarlow and Stutz2013) and, until the 2010s, archaeologically invisible mortuary practices were largely relegated to prehistory in Britain. It is only a growing understanding of Roman non-burial that makes it possible to recognise the probability of non-burial practices in the Early Middle Ages.

Other recent research elsewhere in northern and western Europe has drawn attention to a variety of non-burial treatments throughout the first millennium AD. These include retention and modification of skeletal parts through the long Iron Age of Atlantic Scotland and into the Norse period (Shapland & Armit Reference Shapland and Armit2012), and practices involving processing, display and deposition of crania into the Viking period in Scandinavia (Eriksen Reference Eriksen2020). In Sweden, customs involving scattering and depositing cremated human remains in non-mortuary contexts persist to the end of the millennium (Thérus Reference Thérus2019). Finds of cremated remains meaningfully deposited outside dedicated funerary contexts have been highlighted in Scotland, and the absence of cemeteries in western Scotland has been taken as evidence that the population in this area practised exposure (Maldonado Reference Maldonado2013: 12; Maldonado Reference Maldonado, Williams and Lippokin press). Work on bog bodies in northern Europe has shown that when disarticulated remains are included, the timeframe in which deposition of isolated corpses in wetland environments took place is hugely extended, continuing beyond its peak in the Iron Age and Roman periods into the Early Middle Ages (van Beek et al. Reference van Beek, Quik, Bergerbrant, Huisman and Kama2023).

Non-burial disposal of the dead can also be found in caves. At Żarska Cave, Poland, disarticulated remains have been radiocarbon dated to the third–fifth centuries (Wojenka et al. Reference Wojenka, Wilczyński and Zastawny2016). In Cantabria, multiple caves contain human remains deposited in short phases of use in the seventh and eighth centuries (Arias et al. Reference Arias, Ontañon, Gutiérrez Cuenca, Gárate, Etxeberria, Herrasti, Uzquiano, Bergsvik and Dowd2018), while in Ireland mortuary cave use stretches from the Mesolithic to the seventeenth century AD (Dowd et al. Reference Dowd, Fibiger and Lynch2006: 17).

In Scandinavia it is particularly apparent that the population is not fully represented in the mortuary record. As late as the Viking Age, more than half of the population may not have received a visible burial (Price Reference Price, Schjødt, Lindow and Andrén2020: 869–70). Across the first millennium AD, both the absolute number and the representative proportions of the dead rose gradually, as increasing quantities of bone from each cremation were deposited in graves (Bennett Reference Bennett1987). Even so, children and females were significantly under-represented until the last phases of grave fields and the first churchyards (Mejsholm Reference Mejsholm2009: 141–43).

A general absence of the dead in the late Roman and early medieval period is observed more widely in the North Sea zone (e.g. Siegmund Reference Siegmund, Green and Siegmund2003: 80–83). In the Frisian coastal area, there is ample evidence for settlement in the Roman period, but the only mortuary finds are occasional burials scattered across the landscape and unburnt skeletal remains in dwelling contexts. There, Annet Nieuwhof (Reference Nieuwhof2015) argues for an archaeologically invisible mortuary custom before the introduction of formal cemeteries in the fifth century.

These examples illustrate that complex non-burial treatment of human remains did not end with prehistory. Yet, even considering disarticulated finds, there is an ‘invisible cohort’ of the dead across substantial areas of Europe, which can only imply that the normative rite was true non-burial that left no archaeological deposits. Such low visibility of the dead implies highly effective forms of disposal. For the British Iron Age, cremation with scattering of remains is rejected as a major practice because pyre sites have not been found (Armit Reference Armit, Bradbury and Scarre2017: 163). Yet even where cremation burials are seen in England in the early medieval period, pyres are rare (Lucy Reference Lucy2000: 106). In the cemetery of Liebenau in northern Germany, rapid windborne deposition of sand preserved the fourth- and fifth-century phases of shallow pyre and cremation deposits, which in normal circumstances would have been lost (Siegmund Reference Siegmund, Green and Siegmund2003: 81–83). The absence of pyre sites should not, therefore, automatically discount cremation without subsequent burial as a means of disposal for the invisible cohort in regions around the North Sea in the early medieval period, and perhaps in the longer term in northern and western Europe.

Making the invisible visible

While full dispersal of human remains leaves little or no archaeological trace, signs may be found of related practices that, due to their nature or location, resulted in incomplete dispersal. Here, we present an analysis of disarticulated human bone recovered from riverine or cave contexts in England and Wales. These provide evidence that a range of forms of non-cemetery disposal of the dead persisted across the first millennium AD.

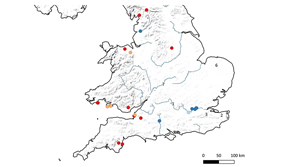

Since stray finds of disarticulated remains by definition lack archaeological context, the only way to assign them to a specific period is through radiocarbon dating. We draw on a comprehensive survey of all radiocarbon data published up to 2016 (Bevan et al. Reference Bevan, Colledge, Fuller, Fyfe, Shennan and Stevens2017), in which we identify 19 finds of disarticulated remains in rivers and caves or of inhumations in watery landscapes in England and Wales between 1950 and 950 BP. We also include seven additional finds sourced from a literature review (Figure 2; see online supplementary material (OSM) Table S1). Some of these dates were produced in the early days of radiocarbon dating and have large margins of error. The majority date to the third–seventh centuries and around one-third of the dataset could feasibly date to the fifth century.

In the karst limestone regions of the north and west of England and Wales, caves provide a specific environment in which exposure could be practised in a way that increased the chance of archaeological recovery. Few caves are found across lowland England (Figure 1, Wilford Reference Wilford2016: 138), but the finds in rivers indicate that alternative means of disposing of the dead outside cemeteries were practised here as well. Four samples from a Neolithic barrow at Coldrum, Kent, which were recently radiocarbon dated to the fifth–seventh centuries (Neil et al. Reference Neil, Evans, Montgomery, Schulting and Scarre2023), give a further indication of possible customs in lowland regions.

Figure 1. Map of human remains from riverine or cave contexts dated to, or likely to date to, the Roman and early medieval periods (figure by authors).

Figure 2. Calibrated radiocarbon dates of human remains from riverine or cave contexts (figure by authors).

The significance of human remains in marginal places has been noted in the Roman period; for example, Alex Smith (Reference Smith, Bradbury and Scarre2017: 48) draws attention to disarticulated remains found around settlements as potential evidence for excarnation. However, the use of marginal environments has not hitherto drawn the attention of early medievalists (Bergsvik & Dowd Reference Bergsvik and Dowd2018: 1), whose focus lies with furnished formal burials, to the explicit exclusion of disarticulate remains (e.g. Sofield Reference Sofield2015: 355–6). Many of the radiocarbon dates included here were generated by prehistorians, for whom cave disposal is an expected occurrence; in such cases, obtaining these late results represents an anomaly that rarely warrants further discussion (e.g. Schulting & Richards Reference Schulting and Richards2002; Meiklejohn et al. Reference Meiklejohn, Chamberlain and Schulting2011).

The numbers of dated remains are relatively small, but disposal in water and caves is on the boundary between what is archaeologically visible and invisible, and what is recovered is likely to be a tiny fraction of what was originally deposited. The necessary reliance on scientific dating further reduces the identifiable sample. For example, Schulting and Bradley (Reference Schulting and Bradley2013) studied 150 Thames skulls but acquired radiocarbon dates on only eight, and of the human remains identified at 462 rural Roman sites by Smith and colleagues (2018: 208), only 13 per cent had associated radiocarbon dates. The finds analysed here also include several where a Roman or early medieval date may be indicated by associated material culture (Table S2). At Dog Hole cave in Cumbria, for example, four bone samples were radiocarbon dated to the first–fourth centuries, but beads intermingled with the remains suggest continued deposition into the fifth–seventh centuries (Benson & Bland Reference Benson and Bland1963: 74; O'Regan et al. Reference O'Regan, Bland, Evans, Holmes, McLeod, Philpott, Smith, Thorp and Wilkinson2020). Many caves have much longer histories of use for corpse disposal, perhaps indicating the same desire to create ancestral links as motivated the reuse of prehistoric burial mounds for early medieval inhumation (Wilford Reference Wilford2016: 327).

Remains found in caves are likely to be related to exposure practices, with large quantities of disarticulated bone indicating disposal in the cave itself. This appears to have been the case at Wookey Hole in Somerset, where the recovery of semi-articulated remains, some showing gnaw marks, indicates in-cave deposition that continued to be practised until at least the end of the fourth century, according to radiocarbon dating and coin typologies (Balch & Troup Reference Balch and Troup1911: 583–84, 591–92; Hawkes et al. Reference Hawkes, Rogers and Tratman1978: 26). In contrast, fragmentary and isolated skeletal elements may indicate that bodies had been exposed elsewhere and token fragments retrieved and deposited in caves, such as at Robin Hood's Cave in Derbyshire, where a single mandible was radiocarbon dated to the second–fourth centuries (Wilford Reference Wilford2016: 302). Some bones may also have been dragged into caves by scavengers, having been exposed elsewhere (Madgwick et al. Reference Madgwick, Redknap and Davies2016: 220).

Skulls, which most readily sink to be preserved in sediment (Turner et al. Reference Turner, Gonzalez and Ohman2002: 429–30), have been recovered from riverine contexts, particularly along the Thames and the River Ribble in Preston (Turner et al. Reference Turner, Gonzalez and Ohman2002). Most of the Thames skulls date from the first millennium BC but some are Roman or medieval (Schulting & Bradley Reference Schulting and Bradley2013: 43). Another possible riverine context is a fishing weir on the River Wey, radiocarbon dated to the fourth–seventh centuries, where disarticulated human remains were found in silt (Bird Reference Bird1999: 116). Cave and riverine contexts are also not entirely separate; there is evidence from Wookey Hole of late Roman disposal of human remains in the river that flowed through the cave (Wilford Reference Wilford2016: 315).

One example that blurs the boundaries between riverine disposal and inhumation burial is a ‘bog body’ found beside the River Avon in Wiltshire and radiocarbon dated to the fifth or sixth century (McKinley Reference McKinley2003). This was a 20–25-year-old female, originally buried prone in waterlogged conditions under a wooden cover. McKinley interprets this as an individual who required confinement in a marginal burial, but this grave could also be seen as part of a broader spectrum of deposition in water.

Human remains may, of course, end up in caves or water as a result of accidents (Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Weisskopf and Hamilton2009: 44; van Beek et al. Reference van Beek, Quik, Bergerbrant, Huisman and Kama2022: 137). Remains found in rivers may also have eroded out of adjacent banks, rather than having been deliberately deposited in the water (Schulting & Bradley Reference Schulting and Bradley2013: 32; Harward et al. Reference Harward, Powers and Watson2015). A skull from the River Ribble in Preston, dated to the seventh–ninth centuries AD, has indications of sharp-force trauma, and may have ended up in a marginal place as the consequence of violence (Turner et al. Reference Turner, Gonzalez and Ohman2002: 428). However, skulls with obvious trauma have been preferentially selected for radiocarbon dating, and so form a disproportionate number of known examples (e.g. Schulting & Bradley Reference Schulting and Bradley2013).

The riverine and cave remains identified in this article cannot represent the entirety of non-cemetery disposal, and nor are they argued to represent a norm. Rather, these finds come from specific environments in which practices that are usually archaeologically invisible become visible. Persistence of such finds into the early medieval period indicates that a spectrum of funerary activity was maintained, and, as contended above, it is likely that this included practices that are truly invisible, such as the scattering of cremated remains.

Conclusion

The longue durée of non-burial mortuary treatment in northern and western Europe probably included much of the first millennium AD. Earlier mortuary practices, including cremation without burial, and perhaps exposure and deposition in water, remained significant components of funerary pathways into at least the fifth century in England.

Low levels of fifth-century mortuary visibility means that the use of burials to understand migration and identity around the Adventus Saxonum frequently relies on sixth- and seventh-century graves. Systematic bias is introduced if the dead treated in the most locally rooted traditions in rural lowland England do not appear in cemetery-based datasets at all.

More widely, increasing awareness of the variety of mortuary behaviours in first millennium northern and western Europe renews the need for consideration of the ontologies of body and person which may relate to changing treatment of the dead over time. Until recently, the key distinction drawn in mortuary rites in the Early Middle Ages was between cremation and inhumation, with the different corpse treatments thought to indicate divergent understandings of relationships between bodies and persons. Now it is widely recognised that cremation and inhumation were often practised alongside each other (Lippok Reference Lippok2020) and could be closely analogous, with the corpse and accompanying artefacts arranged on the cremation pyre in a manner similar to inhumation displays (Nugent Reference Nugent, Cerezo-Román, Wessman and Williams2017). We suggest that the more profound separation in mortuary pathways is found between readily visible rites, which first present the corpse and its accoutrements and then create a grave as a preserving space, and rites that aimed to disperse the physical presence of the dead.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Sophie Bergerbrant, Catherine Hills and Cecilia Ljung for their advice.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or from commercial and not-for-profit sectors.

Online supplementary materials (OSM)

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2024.147 and select the supplementary materials tab.