Introduction

Two- and three-dimensional representations of phalli were ubiquitous in the Roman world. Their widespread occurrence is suggested to reflect erotic concerns, as well as magical and apotropaic functions (Johns Reference Johns1982). They are commonly found depicted in mosaics and painted as frescoes or on ceramic vessels, incised on walls and other surfaces, and rendered in relief or in the round. Most archaeologically documented examples of phalli are made of metal, stone or bone, or occasionally ceramic (e.g. Neilson Reference Neilson2002; Parker Reference Parker and Parker2017). They have been discovered installed in fixed locations, in both public and private buildings, but it is in portable form that phalli are most numerous and diverse (e.g. Zarzalejos Prieto et al. Reference Zarzalejos Prieto, Aurrecoechea Fernández and Fernández Ochoa1988; Whitmore Reference Whitmore, Parker and McKie2018; Collins Reference Collins, Ivleva and Collins2020; Parker Reference Parker, Ivleva and Collins2020). Portable phallic representations might be incorporated into composite objects: British examples include a decorated knife handle (e.g. at Corbridge, Northumberland; cat. no. CO22077) or the terminals of fist-and-phallus pendants known throughout the Roman world (e.g. in Britain, five such pendants were found in an infant burial at Catterick, North Yorkshire; Parker Reference Parker2015). They may also constitute part of the wider practice of manufacturing votive offerings in the form of body parts (Hughes Reference Hughes2017). Small, portable disembodied phalli, with or without testicles, are most commonly found as pendants, probably intended to serve an apotropaic function. Typically, such pendants were cast in metal or carved from bone, although a wooden pendant has been recovered from Masada, Israel (Stiebel Reference Stiebel, Marzel and Stiebel2014: 160, fig. 8.2; Parker Reference Parker, Ivleva and Collins2020: 93). In contrast, larger (i.e. non-miniature) disembodied phalli are uncommon, though when encountered, are also typically made from stone or metal.

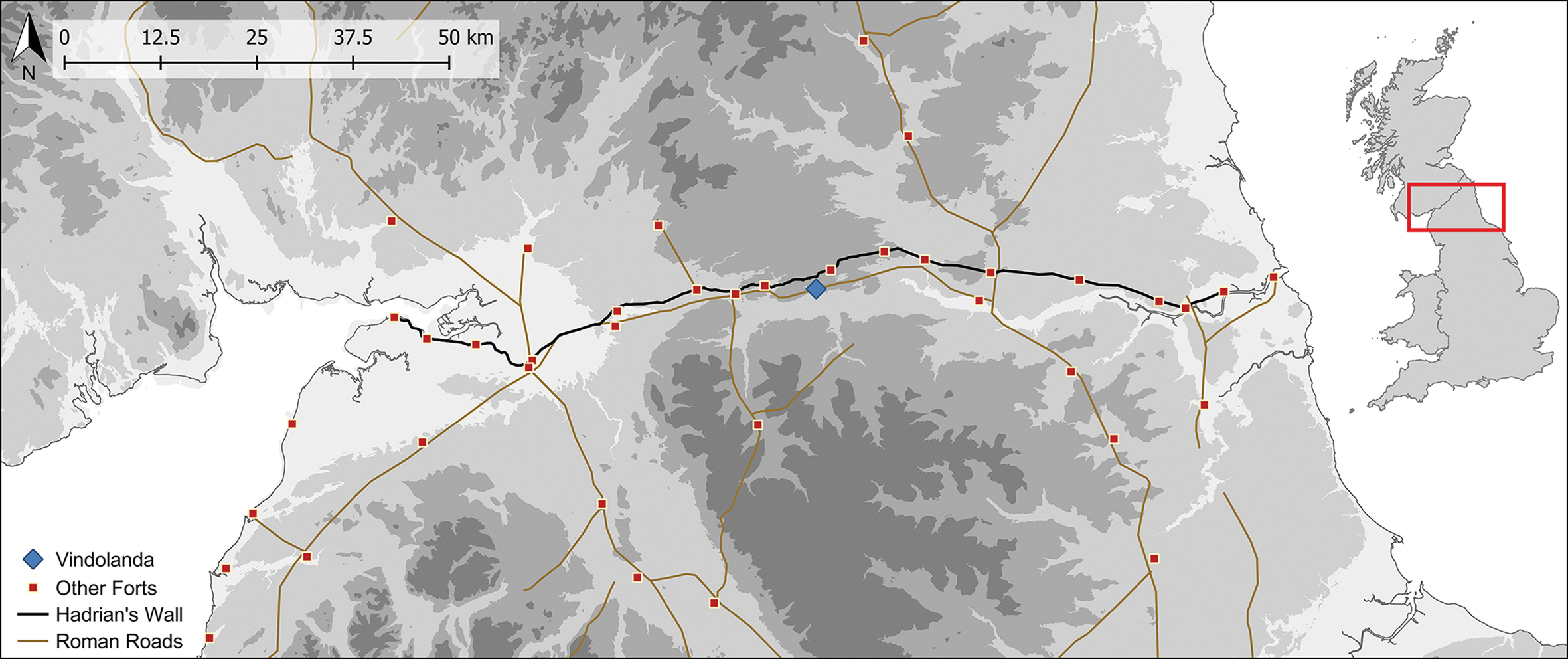

While the archaeological record is only a partial representation of past activity, wood is particularly under-represented. Most wood probably rotted or was burned and hence never entered the ground; that which did typically decays rapidly unless buried in very particular circumstances. One such example are the wet, anaerobic conditions at the Roman fort of Vindolanda in Northumberland (Figure 1), which have preserved some 2000 portable wooden objects, primarily dated to later first- and second- century AD contexts. Among these finds, one object recovered in 1992 from a ditch fill and otherwise unpublished, was recorded at the time of recovery as a darning tool; here, we reinterpret this wooden object as a disembodied phallus.

Figure 1. Location of Vindolanda Roman fort (map by K. Murphy, Newcastle University, using Hadrian's Wall GIS datasets (Garland Reference Garland2020a, Reference Garland2020b, Reference Garland2020c)).

Although no other archaeological examples are known to the authors, probably reflecting preservation bias, it is a reasonable assumption that non-miniature, disembodied wooden phalli existed during the Roman period (Parker Reference Parker and Parker2017: 118; Collins Reference Collins, Ivleva and Collins2020: 279). Such objects are, however, known from other periods and regions. A collection in the Fitzwilliam Art and Antiquities Museum of the University of Cambridge includes four examples from New Kingdom Egypt (c. 1550 BC), although they are not ascribed any function, except for “an obvious reference to fertility” (Fitzwilliam Museum n.d.). Wooden phallic objects recovered from Bronze Age graves at the Xiaohe-Gumugou cemeteries in the Tarim Basin, China, provide examples from burial contexts (Yunyun Reference Yunyun2019: 44, fig. 27), and numerous examples are known from temple and shrine contexts in Japan, such as a collection of six nineteenth-century AD phalli from the Azuma Shrine (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Gerstie, Ishigami and Yano2013). While these objects provide useful comparanda, however, they almost certainly had differing functions and significance in their respective cultures, and therefore do not directly aid the interpretation of the Vindolanda phallus.

Here, therefore, we assess this uniquely preserved object—currently the only known example of a non-miniaturised, disembodied carved wooden phallus from the Roman world. Combining current theories about the role of phallic representations with consideration of the size and form of the object, and potential use-wear, we propose three possible explanations for its use and significance at Vindolanda in the second century AD and reflect on its broader significance for studies of Roman sexuality and magic.

The object, its material and production

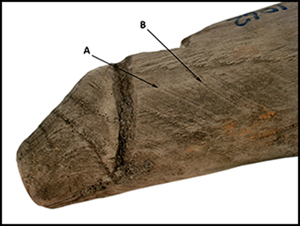

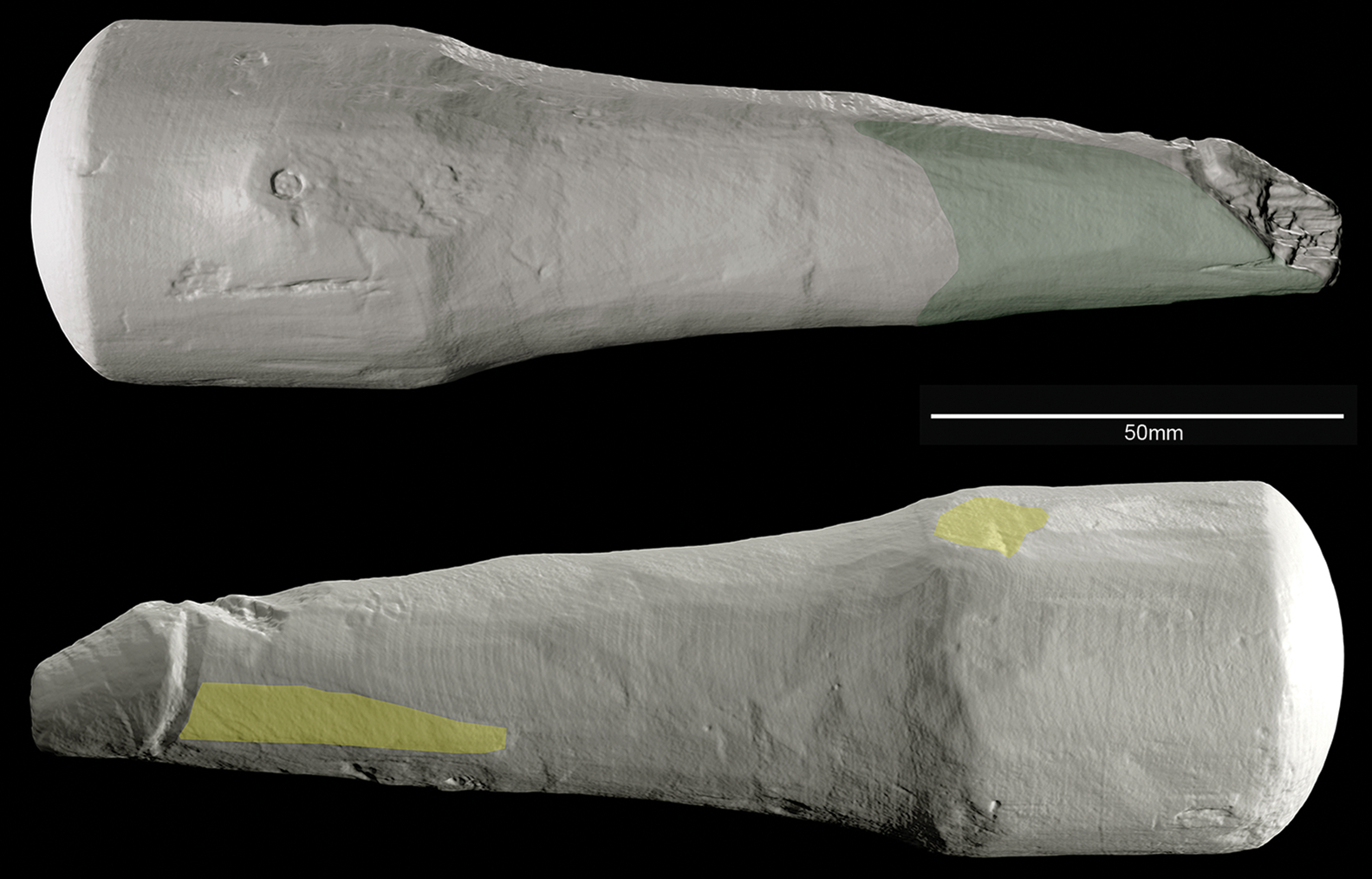

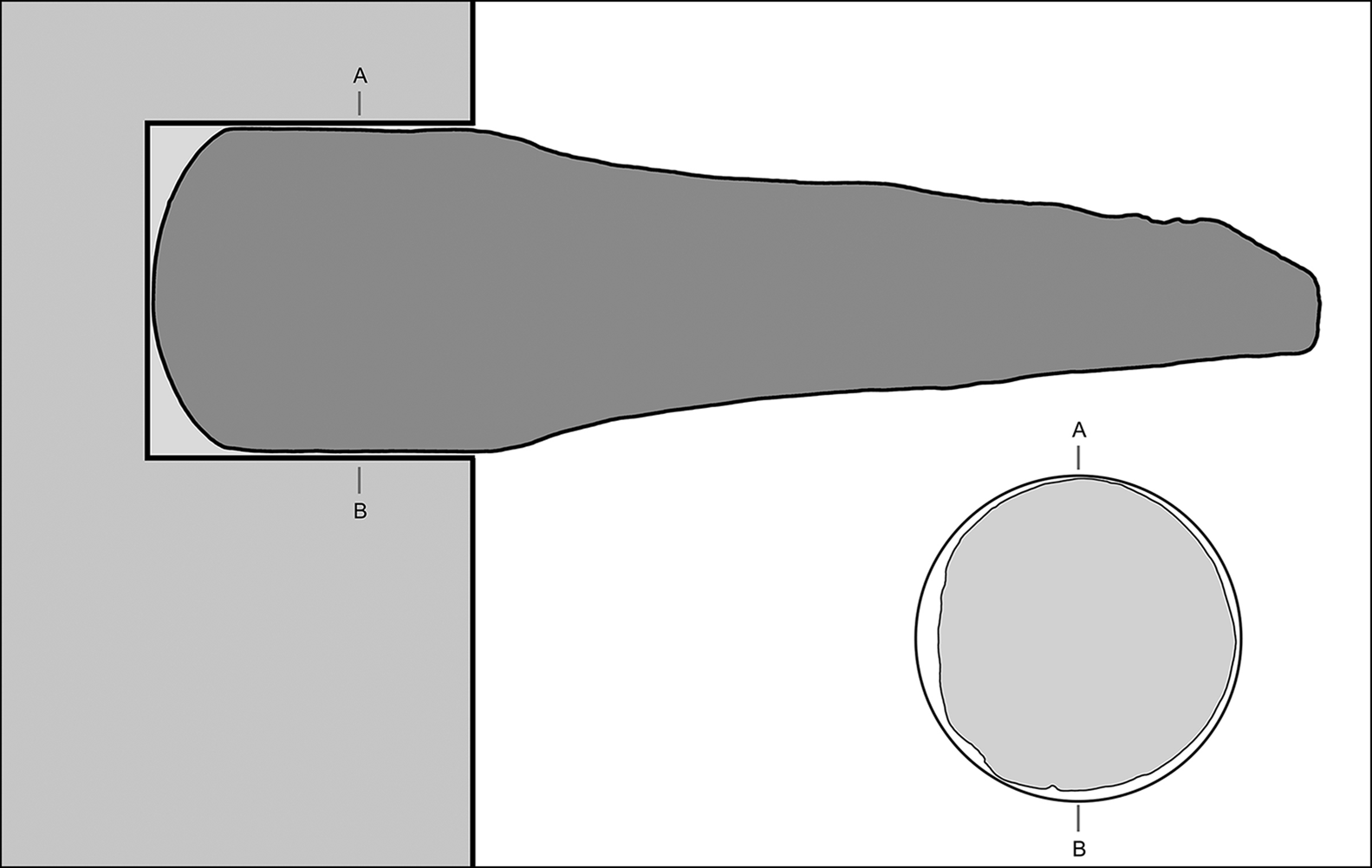

The object (W-1992-1062) is 160mm long and carved from young ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.) roundwood, with a wide, cylindrical base bearing a convex end, narrower shaft and a terminal shaped to depict the glans (Figure 2; key measurements in Figure 3). The glans is distinguished from the shaft by a 27mm-long incised penannular line (1–3mm wide) extending around just over half (approximately 55 per cent) of the circumference of the upper shaft. Archaeological wood is prone to shrinkage and warping, and all measurements given here are post-conservation, probably representing an underestimate of the original dimensions. The object, however, is still approximately round in cross section and symmetrical in profile and plan, so any changes in dimensions are likely to be proportionate to one another.

Figure 2. Object W-1992-1062 from Vindolanda (photographs by R. Sands).

Figure 3. Key measurements of object W-1992-1062 (illustration by R. Sands, using 3D data files relit and rendered in Blender).

The object is neatly fashioned, having probably been whittled with a single tool. Little technical proficiency was required, but an economy of line creates the intended visual outcome. The individual cuts appear assured and symmetrical, with no evidence for mistakes. Consequently, although simple in form, the object suggests the confident hand of a person used to thinking in three dimensions and familiar with working wood. It is possible that the object was made from recycled wood, and there is precedent for this at Vindolanda and elsewhere (Sands Reference Sands2021); however, the clear cuts and the well-defined tool marks suggest that the wood was not fully seasoned when shaped into a phallus and probably, therefore, the object is not from recycled wood.

Context and deposition

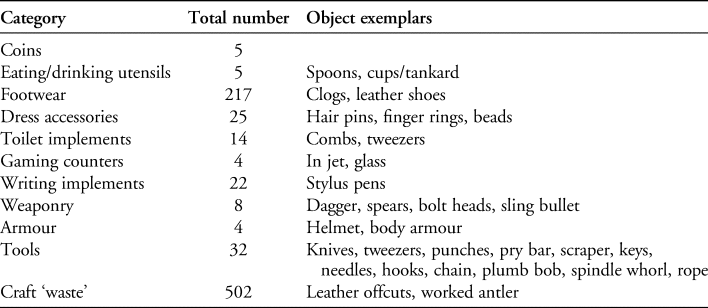

Vindolanda consists of at least nine discrete, successive forts of varying sizes, occupied from the later first century AD until the early–mid fifth century, with uncertain levels of occupation extending possibly as late as the tenth century (Birley & Alberti Reference Birley and Alberti2021). The occupation, demolition and rebuilding of these forts has resulted in deep, sealed anaerobic deposits. The wooden phallus was recovered from a deposit within a Phase VIA (AD 165–200) ditch, which defined the outer perimeter of the stone-built Antonine-period fort. The object was not clearly located at the ditch terminals or in other spatially ‘significant’ places where structured deposits are frequently encountered. A total of 838 partial or complete objects were recovered from the same context (Table 1), representing a typical assemblage for a ditch fill at Vindolanda, and nothing indicates the special selection of objects for deposition. Consequently, assuming that the phallus was not redeposited and accepting the complexity inherent in identifying structured deposition (see Garrow Reference Garrow2012), the object appears to have been deposited as part of a ‘normal’ process of discard or loss at the site. The ditch context therefore provides a general late second-century terminus ante quem but offers no further insight into the function of the discarded phallus.

Table 1. Summary of select objects, sorted by functional categories, found in the Antonine ditch fills at Vindolanda in general proximity to the wooden phallus.

Condition and wear

Repeated use of wooden objects can damage or smooth their surfaces, depending on the intensity and frequency of handling and/or the time over which they were used. Other factors, such as the transfer of sebum from the skin during handling, may lead to the polishing of surfaces. The density, hardness and flexibility of wood varies between tree species; we should thus expect some types of wood to be more resistant to wear than others. The results of studies of these properties, however, indicate the complexity of wood as a material (Bartolucci et al. Reference Bartolucci2020). As a living, organic material, there is also variation in the wood from individual trees. Differences in growing conditions (e.g. sunny vs shady, open vs tightly spaced, growing on flat vs sloping ground) can result in quite different products. Wood is also orthotropic (i.e. its characteristics vary according to orientation) and hygroscopic (i.e. it can exchange moisture with its environment), meaning that it can shrink and expand (Harte Reference Harte and Forde2009). Consequently, wood can vary mechanically even when originating from trees of the same species and can further alter after felling. Making predictions about how individual wood samples will respond to shaping and wear is complex.

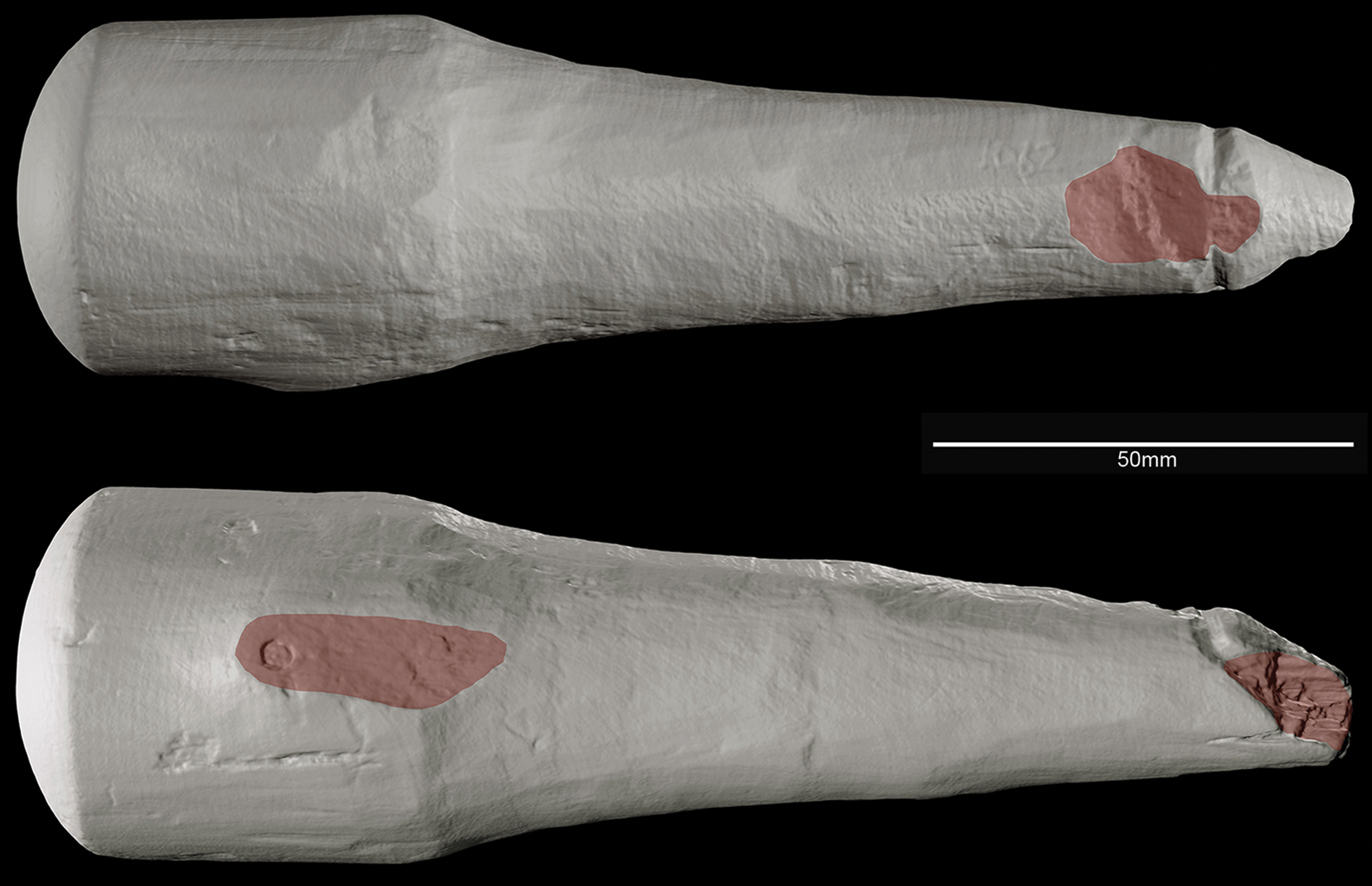

Whether the wear patterns observed on archaeological objects are the result of usage is further complicated by post-depositional changes. Even when deposited in ideal, consistent conditions, changes to the structure of the wood will occur. The reasons are complex (e.g. Orr et al. Reference Orr2021) and the evolving science need not be rehearsed here. The consequences of structural change, however, are relevant; an object may appear structurally sound but can easily be damaged after deposition, during recovery, or as part of the conservation process. Some areas of damage on the Vindolanda phallus, for example, are best attributed to post-depositional activity (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Main areas of damage on object W-1992-1062 (illustration by R. Sands, using 3D data files relit and rendered in Blender).

One approach to identifying use-wear is to ‘calibrate’ our observations using other objects from the assemblage whose function and use can be more confidently assumed. A handle from a framesaw, also made of ash, for example, suggests that repeated gripping during the sawing motion, combined with the oils from the skin, has smoothed the wood. The original carved surface of the handle shows signs of a polishing effect, the surface retains a slight sheen, and it feels smoother to the touch at exactly the point where the user's grip would have been strongest (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Ash wood framesaw handle (W-1987-0341) from Vindolanda, indicating wear of the handle through use (photographs by R. Sands).

Having established that conditions at Vindolanda allow for the survival of use-wear traces on objects made of ash wood, we can examine the wooden phallus in the expectation that we might observe wear attributable to its handling before deposition. The object's overall level of preservation is generally very good: it retains a broadly symmetrical shape, suggesting stability in form over time, and traces left by minute damage in the blade used in production survive in one area (Figure 6), indicating that, in this area at least, the object has not been extensively handled. This good surface preservation also suggests that the phallus was not exposed to the elements for any extended period before deposition.

Figure 6. Close-up of toolmark signatures on object W-1992-1062. Arrows A and B show two different applications of the same tool (photograph by R. Sands).

The wooden phallus has been three-dimensionally scanned by Rhys Williams at Teesside University, as part of a wider scanning programme of objects from Vindolanda. The results reveal useful details, including of the faceted worked surfaces, and permit the extraction of cross sections (on method, see Williams et al. Reference Williams2019: 6–7). Relative surface smoothness, however, is complex to capture. Techniques for recording surface microtopography have been developed, but their application within archaeological studies has so far focused on inorganic materials (e.g. Martisius et al. Reference Martisius2020). Three-dimensional techniques have previously been used to record wooden surfaces, including fine-scale features such as toolmarks, or to assess broader changes in surface morphology (e.g. Høgseth Reference Høgseth2007; Lobb et al. Reference Lobb2010), but no study, to our knowledge, has sought to quantify the smoothness of wood.

Despite technological advances, touch still provides a very valuable qualitative assessment and can reveal subtle variations in the roughness or smoothness of surfaces not immediately apparent or available in images or scans (e.g. Skedung et al. Reference Skedung2013). Tactile examination of the Vindolanda phallus reveals that the convex base end is smooth, which we attribute to intentional shaping during manufacture and/or exposure to repeated contact through use. A zone approximately 40mm in length along the underside and lateral faces of the shaft and an area 30–40mm long at the tip (upper shaft, glans and area behind it) were also notably smoother than other surface areas, possibly indicating repeated contact (Figure 7). The greater wear of the convex end and sides of the cylindrical base and the glans terminal may be significant for interpretation of the object's function. Put simply, assuming such wear was caused by use, the phallus has perceptibly greater wear at either end compared with its middle.

Figure 7. Main smooth area on object W-1992-1062 (shown in green), and key areas of toolmarks with signatures (shown in yellow). Note that facets are visible across the object; shorter and smaller examples occur as the carver adjusts the angle between the shaft and the base (illustration by R. Sands, using 3D data files relit and rendered in Blender).

Function and significance

What function or functions might the wooden phallus have served? We consider three possible interpretations: a projecting component (of a herm, statue or building), a pestle, or a sexual implement.

Projecting component

Herms were found throughout the Graeco-Roman world. Often positioned near doorways, where passers-by could touch one to receive protection, a herm took the form of a stone monolith with a carved head and phallus (with or without testicles). The phallus was sometimes carved separately and inserted into the monolith. Also known from the Roman world are phalli that were mounted on buildings or structures. At Vindolanda, for example, a 0.28m-long sandstone phallus recovered from a rubble collapse may originally have projected from the stone wall of the third-century fort's west gate, serving an apotropaic function to protect a liminal location vulnerable to breach by individuals with ill will or evil intent (Collins Reference Collins, Ivleva and Collins2020: 288). One possible interpretation of the Vindolanda wooden phallus is that it was intended to be slotted into another object or structure. The round cross-section of the phallus would fit snugly into a socket (Figure 8). The convex shape of the base, however, would reduce the stability of the phallus and require a deeper socket to fix it securely in place. The wear on the base, particularly the convex end, is consistent across the entire surface, which seems unlikely if the base was in a socket. Additionally, the clear edge distinguishing the convex end from the sides of the base suggests that it was not repeatedly removed and reinserted.

Figure 8. Assessment of the fit of the phallus base if placed into a socket as a herm (illustration by R. Sands, using sections extracted from 3D data files using Meshlab).

The wooden phallus may originally have been positioned to project from, and provide protection for, the entrance to one of the key buildings inside the fort, such as the commanding officer's house (praetorium), the headquarters building (principia) or the granaries (horrea). The lack of surface weathering, however, suggests that, if used in such a way, the phallus was either kept indoors or in a sheltered location, or at least was not placed in an exposed position for any appreciable length of time.

Alternatively, the phallus could have been intended for insertion into a carved figure. A wooden statue from the wreck of an early first-century AD merchant vessel found near Marseille, provides an example of a carved wooden figure with a socket intended to hold a separate phallus (L'Hour Reference L'Hour1984: figs 13–15). This figure has been interpreted as Priapus, typically shown as lifting his tunic to expose an erect phallus (Neilson Reference Neilson2002: 250). A popular lesser deity, Priapus is best known through 80 first-century AD Latin epigrams, known as the Carmina Priapea (Parker Reference Parker1988; Codoñer & Iglesias Reference Codoñer and Iglesias2015; Elomaa Reference Elomaa2015). Sculptural representations of Priapus are intentionally ‘rustic’, lacking sophistication, and reflecting an association with the agricultural world (Meiggs Reference Meiggs1982: 324; Codoñer & Iglesias Reference Codoñer and Iglesias2015: 320). An association between Priapus and “woodenness” (Elomaa Reference Elomaa2015: 32), and his status as a “shabby wooden idol” (Richlin Reference Richlin1992: 141) gave licence, in some contexts, for ridicule. There are also direct textual references to tree species associated with Priapus, or from which his effigy could be made, such as fig, apple, poplar and oak (Meiggs Reference Meiggs1982: 324; O'Connor Reference O'Connor1982; Elomaa Reference Elomaa2015: 31 & 95). There is, however, limited archaeological evidence with which to assess the use of certain types of wood, and literary convention might not reflect actual practice (Meiggs Reference Meiggs1982: 324).

If the Vindolanda phallus formed part of a statue, the fact that it was detachable may have had some significance and may have playfully reflected Priapus’ concern that his penis is a “prosthetic attachment” (Hunt Reference Hunt2011: 42), at once potent and impotent. The texts often portray Priapus as a figure of amusement, and there is certainly humour throughout the Carmina Priapea. While archaeologically elusive, such emotions are part of the human condition and must have played out in various aspects of material culture. The link between phallic representations and/or sexual imagery with humour is well attested in the Roman world; indeed the inducement of laughter was partly what empowered the phallus to counter the evil eye (Richlin Reference Richlin1992; Clarke Reference Clarke2001; Pearce Reference Pearce, Ivleva and Collins2020). Another parallel is found in the ‘grotesque’ figure from a third century AD well in the extramural settlement of Rainau-Buch, Germany, where a wooden phallus made use of a cylindrical socket for insertion into the carved wooden figure (Greiner Reference Greiner2008: 214–215). Thus, detachable phalli need not be exclusive to Priapus.

Silvanus is another deity potentially associated with phallic imagery. A god of woodland and the countryside, Silvanus is sometimes depicted as ithyphallic (i.e. with an erect phallus), and Hunt (Reference Hunt2016: 87–89) points to a second-century AD inscription from Gallia Narbonensis that associates the deity with an ash tree or possibly a statue carved from ash (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum, CIL 12.103; Hirschfeld Reference Hirschfeld1963). While Silvanus is named at Vindolanda on an altar of the later second to third century AD (Roman Inscriptions of Britain, RIB 1696; Collingwood & Wright Reference Collingwood and Wright1965), and he is mentioned in a further 26 altars from Hadrian's Wall and its northern and southern hinterlands (e.g. RIB 972, RIB 1790), no statues of Silvanus are known from the northern British frontier. Thus, while Silvanus was certainly worshipped, at present there is no evidence in the British frontier to indicate that worship included statuary representation.

Comparison to a wooden phallus (E57b) attributed to New Kingdom Egypt (Fitzwilliam Museum 2020) and the Roman figure from Rainau-Buch points to other elements that might be expected if the Vindolanda phallus were intended to be fitted into a herm, statue or structure. The Egyptian phallus has the remains of a cylindrical metal shank projecting from its flat base, as well as worn and rounded edges around the base, suggesting that it fitted into a socket. The absence of such features on the Vindolanda phallus may be significant, potentially arguing against the possibility that the object was intended to form part of a composite sculpture or be mounted on a structure.

A pestle

An alternative interpretation, suggested by the convex shape of the base of the phallus is that the object was used as a pestle. The uniform convex and smooth basal surface may have resulted from grinding, or mixing, materials, while the greater wear on the other end of the phallus may indicate where it was held during the process. We need not assume that the material being ground was hard and abrasive, and the mortar against which the pestle would have been pressed could also have been made of wood. There is no obvious staining or discolouration on the putative grinding surface, although the presence and survival of such evidence depends on the specific circumstances of use and preservation.

The use of pestles and mortars in the Roman period encompasses a range of activities, some of which are known from contemporaneous literature. Recent analytical investigations of mortaria from Iron Age and Roman Britain show that they were used to grind or mix both animal and plant products (Cramp et al. Reference Cramp, Evershed and Eckardt2011: 1341). This need not only be for culinary purposes; cosmetics or the blending of unguents or medicines are equally possible. A phallus-shaped pestle might symbolically add efficacy, or protection, to whatever was being prepared in the mortar, the act of grasping and grinding being the vehicle through which magic was activated (Lee Reference Lee2021: 288). The idea that pestles and mortars might be charged with sexual metaphor and power is not new. Mithen and colleagues (Reference Mithen, Finlayson and Shaffrey2005), for example, drawing on numerous anthropological examples, suggest that phallus-shaped stone pestles from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic in the Southern Levant may be considered in this way.

A phallus-shaped pestle might also have Priapic associations, reinforcing the potency discussed above. Examples of Priapus represented in any media are rare from Britain in general, and on the northern frontier in particular. A notable exception is a stone carving from a fourth-century AD context at Vindolanda. It was found face down on a flagstone surface, close to a food preparation bench, its flat back suggesting that it might originally have been set in a wall niche. The kitchen context provides a link to the fertility of gardens and garden produce (Birley Reference Birley, Birley and Blake2007: 38–39), and the presence of a phallus-shaped pestle in a kitchen might have similar resonance. Interpreted in this way, we might argue for some Priapic agricultural parallel with the phallic form of the wooden handle of a scythe from the Blackburn Mill hoard in the Scottish Borders (Piggott et al. Reference Piggott, Burgess and Henshall1955: fig. 12, B34).

Sexual implement

While the symbolic and apotropaic use of phalli in Roman contexts is persuasive, their use as sexual implements should not be dismissed. Phallus-shaped objects used for sexual stimulation are commonly referred to as dildos, and within contemporary research the term ‘sex toy’ is accepted. The word ‘toy’, and all that this implies, however, may be inaccurate or anachronistic in historical contexts. Use may not have been exclusively sexual or for the pleasure of the user. Such implements may have been used in acts that perpetuated power imbalances, such as between an enslaved person and his or her owner, as attested in the recurrence of sexual violence in Roman literature (Kamen & Marshall Reference Kamen and Marshall2021).

The history of sex toys has received limited academic attention. Lieberman's (Reference Lieberman2017) popular history of sex toys in the USA includes some discussion of their use in earlier periods across the world but directs limited attention to the material evidence. We can assume, however, that such objects existed in other past societies, and this is strongly supported in texts and artistic representations from the Graeco-Roman world (Nelson Reference Nelson2000; Clarke Reference Clarke2001). Yet they rarely feature in archaeological finds registers or discussions, and there are limited archaeological comparanda. Public propriety in Western cultures over the past 200 years may be one reason for this scarcity. Another may be that dildos were more likely to be made from organic materials and therefore do not routinely survive. Definitive archaeological examples are generally of more recent date. In 2015, for example, excavation of an eighteenth-century fencing school in Gdańsk uncovered a leather dildo (yet to be formally published, though see Kisicka Reference Kisicka2019). From a similar period in France are two godemichets made from rosewood, a fine-grained material with smooth, tactile properties, which were sold at auction for £3600 (BBC News 2010). The choice of organic materials with smooth surfaces is also illustrated by an eighteenth-century ivory example found in the stuffing of a seat of a Louis XV armchair in a convent on the banks of the Seine in Paris (Science Museum Group n.d.).

Demonstrating that the Vindolanda phallus was used as a sexual implement is challenging. Although it explicitly imitates the anatomical form of a penis, modern implements are morphologically more diverse than human physiology; form alone is therefore not indicative. Nor does the size of the Vindolanda phallus preclude its use in this manner. Lubricants may be expected, but neither these nor human secretions are likely to survive archaeologically. Exactly how use-wear might manifest on an object of this type is also unclear and variations in use may be a factor. Research points to different perceptions, attitudes and uses of modern dildos across different genders and sexual orientations (Rosenberger et al. Reference Rosenberger2012; Fahs & Swank Reference Fahs and Swank2013). In this regard, if the Vindolanda phallus functioned as a dildo, it need not necessarily have been used for penetration. Instead, actions such as clitoral stimulation might better fit the form and wear observed. Different modes of use, presumably, produce differential wear, but no definitive research exists, to our knowledge, that demonstrates this. Comparison of wear patterns on the Vindolanda wooden phallus with known examples of dildos is also difficult. The greater wear observed on the glans and upper shaft on the Vindolanda phallus compares favourably with the eighteenth-century ivory example noted above, in which differential surface colour and smoothing can be observed, even on photographs. Similarly, greater wear of the glans is observable on a stone double-dildo of the Sui dynasty (AD 581–618) in China, with double-dildos in Chinese historical texts typically described as made of ivory or wood for use in lesbian sexual acts (Ruan Reference Ruan1991: 139).

Conclusion

Phallic representations in Roman culture are typically assumed to have served magical, apotropaic or symbolic functions. The Vindolanda phallus, without a clear use context, is more ambiguous. It underscores the ubiquitous presence of the phallus in Roman culture, while also highlighting the limitations of current archaeological knowledge.

The possible interpretations discussed in this article arguably reflect two broader perspectives. The first is representational: the erect phallus acts as a symbol to be read by the viewer or user and applied to a context of use. This places the object within a wider framework of phallic representation in the Roman Empire, with all the complexities and ambiguities of use and of group and personal identities that this might imply. Whether as a herm or a pestle, the relatively modest size of the object suggests that it was probably used or perceived at a more individual than communal level, adding potency or invoking a specific magical or apotropaic force for a limited number of people. The second perspective, viewing the object as a ‘sex toy’ implies that its form is intended to mirror reality, and its function aligns with that sense of replication. Rather than invoking something that an erect phallus represented, it acted in the place of a phallus: its form indicates its function. Nonetheless, this second perspective does not preclude symbolic potency, and as noted above, such ‘toys’ need not invoke pleasure, but could also perpetuate power imbalances.

Interpreting the Vindolanda phallus as part of a herm or as a pestle laden with symbolic power via its phallic form is clearly paralleled by a range of objects from the Roman world and is therefore unproblematic. For various reasons, interpreting the Vindolanda phallus as a sexual implement is more difficult, and perhaps uncomfortable, for a modern audience. Nonetheless, we should be prepared to accept the presence of dildos and the manifestation of sexual practices in the material culture of the past. Such a possibility forms part of the narrative of communities such as those living at Vindolanda and beyond, illuminating necessary debates concerning how we acknowledge the complexity of identity manifested in the archaeological record. Although we conclude here with no definitive interpretation of the Vindolanda phallus, we hope to have prompted the search for similar objects elsewhere and encouraged their meaningful incorporation into narratives of the past.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Vindolanda Trust for access to the object and provision of further information to support research. Rob Sands acknowledges support from the School of Archaeology, University College Dublin. Rob Collins thanks Nina Willberger for further information on the ‘grotesque’ figurine from Rainau-Buch. Both authors benefitted from useful discussions with Adam Parker.

Illustrative and data acknowledgments

Table 1 is by Rob Collins, summarising data provided by Andrew Birley, Vindolanda Trust. The original 3D model was provided by Rhys Williams, Teesside University, and is available to view on Sketchfab at: https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/roman-wooden-phallus-c8fe49ba8be64c02b3778b59eb8760d2. The 3D method is described in Williams and colleagues (Reference Williams2019).

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or from commercial and not-for-profit sectors.