In 2018, the Kazakh archaeologist Dr Azilkhan Tazhekeev re-examined materials from earlier, Soviet-era excavations in south-west Kazakhstan. Among unidentified wooden objects discovered in 1973, he reports recognising the substantial remains of two stringed musical instruments, one of which is embellished with engraved decoration (Tazhekeev Reference Tazhekeev and Sarov2019). Tazhekeev dates the objects to the fourth century AD. He suggests that they represent a hitherto unattested ancient form of the traditional Kazakh instrument kossaz, a double-necked lute. The published images, however, reveal another, more remarkable point of comparison: an astonishingly close resemblance to contemporaneous instruments found in Western Europe, specifically, lyres of the type most famously known from the early seventh-century Sutton Hoo ship burial (Bruce-Mitford & Bruce-Mitford Reference Bruce-Mitford and Bruce-Mitford1970, Reference Bruce-Mitford, Bruce-Mitford and Bruce-Mitford1983). In size and shape, and method of construction, the two traditions appear barely distinguishable; and from the implied kinship emerges a remarkable answer to a question that has tantalised Western archaeologists and music historians alike. Although the European distribution of lyre finds currently extends from the pre-Roman Iron Age to the Middle Ages, from Scandinavia to northern France, and from the British Isles to southern Germany (Kolltveit Reference Kolltveit2000; Bischop Reference Bischop, Hickmann, Kilmer and Eichmann2002; Theune-Grosskopf Reference Theune-Grosskopf2004, Reference Theune-Grosskopf2006, Reference Theune-Grosskopf2010; Lawson Reference Lawson, Blackmore, Blair, Hirst and Scull2019a, Reference Lawson, Eichmann, Fang and Koch2019b), evidence of their wider context has been entirely lacking in the archaeological record. So, to what extent were lyres of the Sutton Hoo type an isolated, largely north-western European phenomenon? Is their absence, so far, from Eastern and Southern Europe real, or merely a consequence of survey bias?

The newly identified finds now suggest that survey bias may have played its part: in other words, in conforming to the wide international connections suggested by the larger Sutton Hoo finds assemblage (Carver Reference Carver2017). The excavation which yielded the Kazakh finds was part of the Khorezmian Expedition, a large-scale, USSR-initiated programme of archaeological and ethnographical fieldwork in Central Asia that lasted from the late 1930s to the mid-1990s (Arzhantseva Reference Arzhantseva2015). They were excavated from a settlement in the Dzhetyasar territory (also transliterated Zhetiasar, Jetyasar and Jetiasar) in the Kyzylorda region, east of the Aral Sea, within the lower basin of the Syr Darya River (Figure 1). This region was one of the corridors of the Silk Roads. Dzhetyasar itself gave its name to the Dzhetyasar Culture, which is characterised by many settlements and necropolises, the latter including kurgan mounds (Levina Reference Levina1996). Most of the Dzhetyasar Culture finds correspond to the first half of the first millennium AD. In the seventh century, Dzhetyasar settlements were abandoned and the population moved downstream, closer to the Aral Sea, where they founded the trading post Dzhankent (Härke & Arzhantseva Reference Härke and Arzhantseva2021).

Figure 1. Maps showing archaeological finds of first millennium AD lyres or parts of lyres, and the location of Dzhetyasar (produced by the author using Google My Maps).

From Western Europe—particularly from Germany and England—an ever-growing number of wooden lyres have been excavated from warrior graves of the first millennium AD (Lawson Reference Lawson, Eichmann and Koch2015). In England, the lyre from Sutton Hoo has become an iconic example of the type, since its publication in Antiquity by Rupert Bruce-Mitford and his daughter Myrtle, a professional cellist (Bruce-Mitford & Bruce-Mitford Reference Bruce-Mitford and Bruce-Mitford1970). It was initially identified as a small harp, due, in part, to the incomplete preservation of the wooden fragments. The accuracy of the Mitfords' reconstruction was confirmed by the decayed lyre discovered in silhouette at Prittlewell, Essex, in 2003 (Lawson Reference Lawson, Blackmore, Blair, Hirst and Scull2019a), and by the waterlogged lyre from Grave 52 at Trossingen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany, discovered in 2001 (Theune-Grosskopf Reference Theune-Grosskopf2006, Reference Theune-Grosskopf2010); the latter is the best-preserved example found so far. Complete with body, soundboard, tuning pegs and elaborate, engraved designs, it consolidates our knowledge of Western European lyres and their technology. Differing from the lyres portrayed in the art of Mediterranean antiquity, such lyres are characterised by a long, shallow and broadly rectangular shape, with a monoxyle (one-piece), hollow soundbox and two hollow arms connected across the top by a crossbar or ‘yoke’. The soundbox is typically curved around its base and is equipped with a small projecting knob for fixing the strings. In all of these respects, the overall shape—and evidently also the technology—of at least one of the Dzhetyasar objects conforms closely to the same scheme.

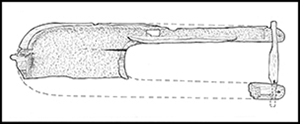

In the best preserved of the finds (Figure 2), approximately two-thirds of the soundbox survives, in addition to one of the arms, a fragment of the second arm, and a crossbar that apparently connected the two arms. The overall length of the object appears to be 0.655m—only marginally smaller than the lyres from Trossingen and Prittlewell, which measure 0.803m and 0.74m, respectively. The arms themselves were seemingly hollowed out along their entire length. The thin soundboard that would originally have covered their cavities, as well as that of the main resonance chamber, appears not to have survived, but this is normal. It is not yet clear how the crossbar was fixed to the arms, and how the strings—of unknown number—were attached to it or to some other, now missing, structure. The hollowing of the arms, the shallow, parallel-sided form of the soundbox and the rounded shape of its lower end, however, all fall entirely within the range of shapes expressed by its European cousins. In short, if it had been discovered in an Anglo-Saxon cemetery, or indeed anywhere else in the West, the Dzhetyasar lyre would not have seemed out of place.

Figure 2. The best-preserved lyre from Dzhetyasar. Length = 0.655m. The soundboard has not survived (drawing by the author, based on photographs and information in Tazhekeev Reference Tazhekeev and Sarov2019).

Conclusion

Dr Tazhekeev is to be warmly congratulated on his discoveries, which prompt a new theoretical model of the origins and geographical range of ‘European’ lyre traditions. Their location in Central Asia now invites an urgent archaeological review of the lyre's easterly distribution, and a new and deeper scientific understanding of this entire family of instruments, its origins and its development. From a more general culture-historical viewpoint, the new information promises to illuminate and enrich our knowledge of early Eurasian music-cultural exchanges. It remains to be seen whether the processes of exchange should be viewed as dynamic transfers of music technology and musicianship from West to East or from East to West, or as a more fluid network of continuous, mutual exchange. Recent archaeological finds in Europe have tended to emphasise and expand the lyre's northward and westward distribution. The Dzhetyasar finds now reveal new vistas to the east: not only south-east to the Byzantine and Levantine worlds, but also due east along the Silk Roads, to distant Samarkand and possibly even beyond.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or from commercial and not-for-profit sectors.