The Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA; c. 9600–8500 cal BC) period in the Levant provides the earliest confirmed evidence for plant cultivation anywhere in the world, marking a significant escalation in the human management of plants towards fully fledged agricultural food production. Until now, the majority of PPNA sites have been documented in the Jordan Valley, the Wadi Araba and farther north along the Upper Euphrates (e.g. Mureybet, Jerf el-Ahmar, Djade). By contrast, few PPNA sites have so far been reported from the semi-arid to arid eastern part of the Levantine interior. Among these is El Aoui Safa (Coqueugniot & Anderson Reference Coqueugniot, Anderson, Kozłowski and Gebel1996) and sporadic flint scatters elsewhere in the Harra. Recent fieldwork in the Qa’ Shubayqa area in the Harra has produced the first evidence for a more substantial settlement site in this region.

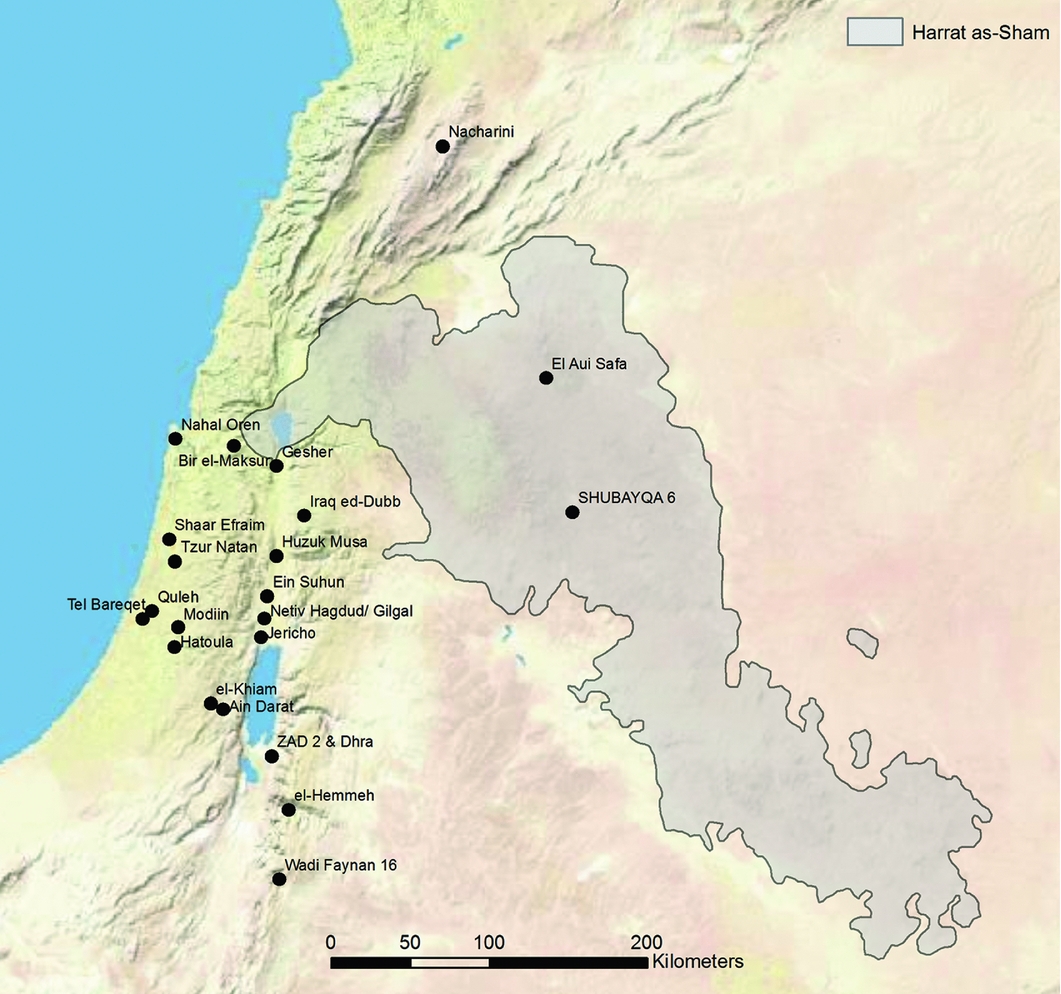

Shubayqa 6 is situated on the northern edge of the Qa’ Shubayqa, around 130km north-east of the Jordanian capital, Amman (Figure 1). The site is one of several late Pleistocene and early Holocene settlements located in this area, which have been under investigation since 2012 (Richter et al. Reference Richter, Bode, House, Iversen, Arranz, Saehle, Thaarup, Tvede and Yeomans2012, Reference Richter, Arranz Otaegui, House, Rafaiah and Yeomans2014). The Late Epipalaeolithic Natufian sites Shubayqa 1 and Shubayqa 3 are situated 0.7km west and 3.1km south-east from Shubayqa 6 respectively. The concentration of settlements in this area is probably due to the existence of a substantial area of permanent wetland that occupied the present basin during the late Pleistocene and early Holocene, providing a wide and rich range of resources (Yeomans & Richter Reference Yeomans and Richter2016).

Figure 1. Location of Shubayqa 6 and other PPNA sites in the southern Levant.

Shubayqa 6 rises two to three metres above the surrounding area, and consists entirely of anthropogenic deposits (Figure 2). Several Byzantine, early Islamic and later structures, as well as a Bronze Age occupation phase, overlie the Neolithic settlement. Chipped stone and ground stone artefacts cover the entire 3000m2 of the mound and the surrounding area.

Figure 2. Aerial photograph and plan of Shubayqa 6 showing the location of the main excavation area.

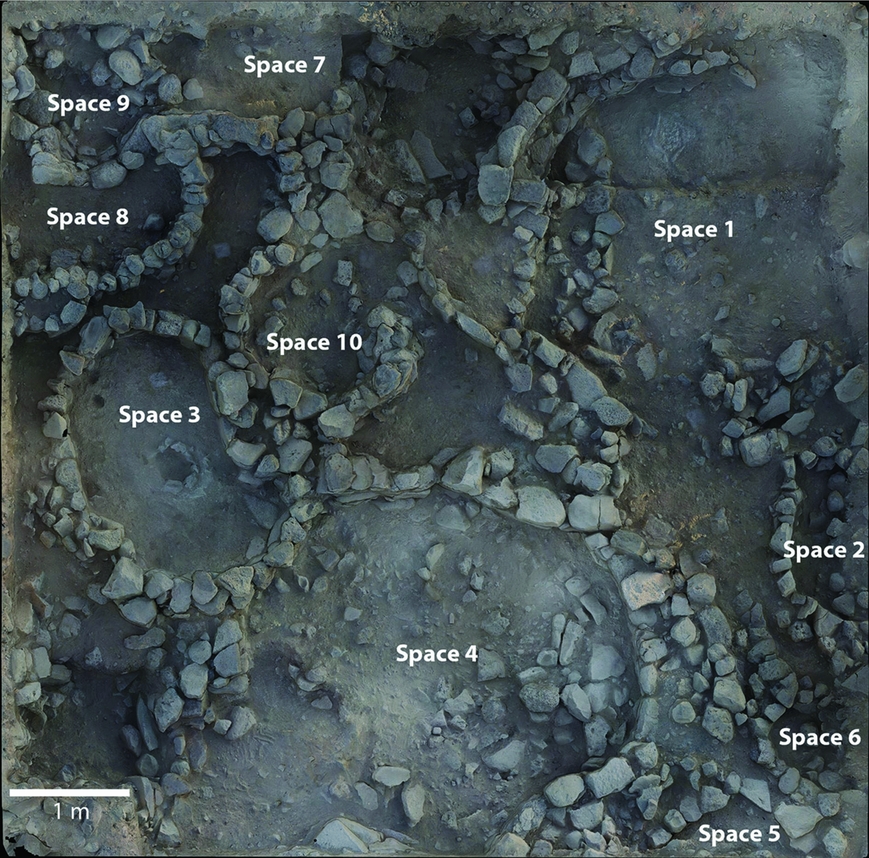

Shubayqa 6 was discovered during a pedestrian survey in October 2012. To date, excavations have revealed a complex series of circular or sub-circular buildings, which reflect the multiple phases of occupation and reuse of the settlement (Figure 3). The structures uncovered so far range from small buildings, less than two metres in length, to buildings with a diameter of four metres. Two larger structures, measuring six and five metres in maximum length have also been uncovered. Although most structures at the site are as yet unexcavated down to floor level, those that have been demonstrate well-made floors and fireplaces.

Figure 3. Close-up view of the main excavation area at Shubayqa 6.

Six AMS dates have been obtained on charred plant material from the site (Figure 4). Apart from one sample that returned a late Chalcolithic/early Bronze Age I date of 3770–3660 cal BC (5710–5610 cal BP 68.2% probability), all other dates fall between 10420–8640 cal BC (12370–10590 cal BP 68.2% probability), covering the time frame between the late Natufian and the late PPNA. These dates are confirmed by the chipped stone material(Figure 5), which exhibits an increase in geometric microliths with depth, while el-Khiam points, drills, flaked axes, sickles and Hagdud and Gilgal truncations dominate the upper layers. The ground stone tools, which are exclusively made of local basalt, include handstones, querns, cup-marked stones, pestles, mortars and grooved stones. Numerous pieces of worked bone have also been recovered.

Figure 4. Plot of the probability distribution of calibrated ranges of 14C dates from Shubayqa 6 in year cal BC and cal BP. Calibrated ages in calendar years have been obtained from the calibration tables in Reimer et al. (Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk-Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013) by means of OxCal v. 4.2 of Bronk Ramsey (Reference Bronk-Ramsey1995, 2001). Samples are ordered according to their stratigraphic position in the site's matrix.

Figure 5. El-Khiam point.

Particularly noteworthy is the large number (2000+) of stone beads, inaddition to unfinished beads and blanks, as well as more than 1.1kg of debitage. These beads are predominantly made of greenstone, although other imported types of stone were also occasionally used. Bead manufacture at the site is also suggested by the large number of flint drills recovered. Art objects are represented by an anthropomorphic chalk figurine (Figure 6) and a T-shaped bone plaque with incisions.

Figure 6. Anthropomorphic chalk figurine.

Organic preservation at Shubayqa 6 is excellent. In addition to a large faunal assemblage, intensive flotation of sediment samples has produced a substantial assemblage of macro-botanical plant remains, which is currently being analysed.

Shubayqa 6 is the first substantial PPNA settlement identified in the Black Desert; it demonstrates that settlement in this semi-arid to arid zone was more intensive than previously thought. The site appears, moreover, to have had occupation that extends across the late Epipalaeolithic to PPNA transition making it one of the few sites in the Levant that combines stratified deposits from these two crucial periods with the preservation of charred macrobotanic remains. Additional work at Shubayqa 6 therefore promises to shed critical new light on the transition from hunting and gathering to food production in the Levant.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Monther Dahash Jamhawi, Director-General of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan, for permission to carry out our research, as well as the Department's staff for their advice and assistance. This project has been funded by grants from the Danish Council for Independent Research, the Danish Institute in Damascus and the H.P. Hjerl Mindefondet for Dansk Palæstinaforsking.