Introduction

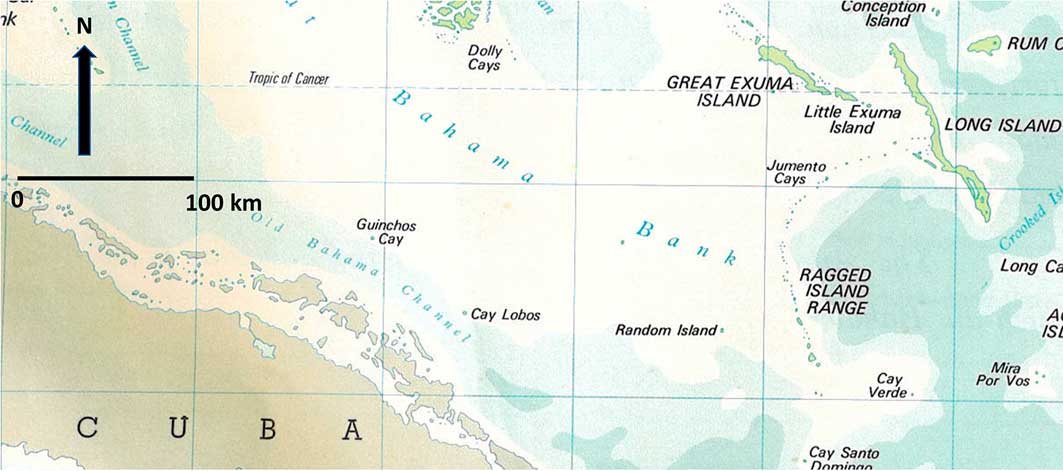

A key unresolved question concerning the colonisation of the Caribbean Islands is whether the initial inhabitants of the Bahama archipelago originated in Cuba, Hispaniola or both (Keegan & Hofman Reference Keegan and Hofman2017). Chronology provides no answers, as the earliest-known sites (c. AD 700–800) are located in both southern and central locations. While connections between the Turks and Caicos Islands and Hispaniola have been investigated intensively, those between the central Bahamas and Cuba have received far less attention (e.g. Sears & Sullivan Reference Sears and Sullivan1978; Granberry Reference Granberry1991; Keegan Reference Keegan1992, Reference Keegan1997; Berman & Gnivecki Reference Berman and Gnivecki1995; Berman et al. Reference Berman, Gnivecki and Pateman2013). Here we investigate possible early connections with Cuba, conducting archaeological reconnaissance of the closest Bahamian cays, namely Guinchos Cay and Cay Lobos—located only 30km from the Islas del Rey (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Location of Guinchos Cay and Cay Lobos (figure by William Keegan).

Archaeological sites recorded in this adjacent Cuban archipelago range in date from 2754–2478 cal BC to European contact in 1492 (Cooper Reference Cooper2007). Thus, the Islas del Rey were occupied millennia before The Bahamas. Although crossing the Old Bahama Channel was within maritime abilities at that time, the main constraint would be finding these tiny, low-lying cays, which are not visible from Cuba. No archaeological evidence was found during survey of Guinchos Cay and Cay Lobos, nor during previous survey of Northwest Cay on Hogsty Reef. While positive finds would have provided important evidence of movement between the islands, the absence of evidence does not mean that these islands were never visited.

Methods

Based on prior research conducted throughout the Bahama archipelago (Keegan Reference Keegan1992), the methods included walkover surveys and shovel testing. All shovel tests were 0.5m in diameter, dug down to sterile sand, with the matrix sieved through 6mm mesh. Walkovers are successful because soil accumulation is slow and natural (e.g. crab burrows). Cultural disturbances expose anthropogenic evidence, and shoreline erosion (e.g. wave action) exposes stratigraphic profiles and artefacts. The most obvious indicators of human activity are the shells of consumed molluscs (e.g. Nerita spp., Codakia orbicularis, Cittarium pica, queen conch (Lobatus gigas), Tellina spp., chiton plates), fire-cracked rock, burnt conch shell and shell tools, coral tools, animal bones and anthropogenic soils. A similar survey of three small islets in the Jumentos Cays (Figure 1) identified six pre-Columbian activity areas, comprising small campsites, procurement areas or waystations used during travel to and from Cuba. Contact was confirmed by the presence of Cuban pottery sherds associated with Bahamian pottery (Keegan & de Bry Reference Keegan and de Bry2015).

Guinchos Cay

Guinchos Cay is essentially a very small, circular low sand ridge, with a sand spit at the north-western corner. The cay is no more than 2m asl (Figures 2–3). We performed a perimeter walkover of the beach-shoreline interface; based on previous surveys, we expected to find archaeological evidence close to the shore. To avoid disrupting nesting birds, the island was not crossed. Furthermore, dense vegetation covered most of the ground surface. The walkover revealed no prehistoric evidence. Three 0.5m2 shovel test-pits were dug, running east at 10m intervals on the rise above the beach near the sand spit. The topsoil comprised 0.2m-thick brown sandy loam, below which was lightly coloured natural beach sand. The soil contained small quantities of water-worn shell, coral rubble and sea turtle bones (in shovel test-pit 2). No anthropogenic evidence was found in the subsurface deposit.

Figure 2 View of Guinchos Cay (photograph by William Keegan).

Figure 3 View of the sand spit on Guinchos Cay (photograph by William Keegan).

Cay Lobos

Cay Lobos has a maximum elevation of approximately 3m asl. The windward shore has a sharp 1m rise from the beach to land, and there is a sand spit to the west. The cay has an abandoned lighthouse and outbuildings, erected in 1869 (Figure 4). Our survey covered the entire cay and its surface. We found no prehistoric evidence, although most of the cay was disturbed by the construction of the nineteenth-century buildings. A contemporaneous foundation at the base of the main dune may have held fresh rainwater (Figure 5). Seven shovel tests were dug at regular intervals around the cay on the rise above the shore. In all of the shovel tests (except shovel test 3, next to a historic kitchen building), the brown sandy-loam topsoil changed to lighter beach sand at about 0.4m deep. Fish bones, mollusc shells and coral rubble were recovered from each of the shovel tests. No prehistoric artefacts were observed.

Figure 4 Lighthouse and sand spit on Cay Lobos (photograph by William Keegan).

Figure 5 Structure foundation on the main dune on Cay Lobos (photograph by William Keegan).

Conclusions

Is the absence of evidence, evidence of absence? Guinchos Cay, Cay Lobos and Hogsty Reef offer low profiles susceptible to storm surges, and have been eroded by wind and wave action over the centuries; any ancient human traces were probably very ephemeral. If these cays were used repeatedly as fishing camps or waystations, then accumulations of mollusc shells and fire-cracked rock would have been apparent. While we found no evidence that these cays were visited by the native inhabitants of the Bahama Islands, we cannot dismiss the possibility entirely. For now, we conclude that they did not play a central role in the colonisation of The Bahamas.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted under the auspices of the Antiquities, Monuments, and Museum Corporation. We are especially grateful to Tim Nielsen, Jimmy Nielsen and Theo Nielsen for assistance in the field.