The past two decades have seen a remarkable increase in the number of Western archaeologists engaged in collaborative field projects in the South Caucasus (contemporary Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia) (e.g. Sagona Reference Sagona2004; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Badalyan and Avetisyan2009; Lindsay & Greene Reference Lindsay and Greene2013; Hammer Reference Hammer2014; Erb-Satullo et al. Reference Erb-Satullo, Gilmour and Khakhutaishvili2015; Franklin Reference Franklin, Bonney, Franklin and Johnson2015; Sauer et al. Reference Sauer, Pitskhelauri, Hopper, Tiliakou, Pickard, Lawrence, Diana, Kranioti and Shupe2015). Simultaneously, the use of geographic information systems (GIS) has emerged as an indispensable digital tool for managing and analysing large spatial datasets in archaeological projects worldwide. High licensing costs, technical demands and paradigmatic differences, however, have prevented research institutions in the South Caucasus from fully implementing GIS workflows. In 2016, a group of 14 scholars from the USA, UK and South Caucasus specialising in GIS and the archaeology of the South Caucasus met at New York University's Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (NYU/ISAW) to assess and improve the state of GIS use in the region.

During the two-day workshop, formal presentations and roundtable discussions highlighted diverse approaches to spatially oriented data collection and analysis, and the unique challenges of conducting GIS and landscape analysis in the post-Soviet research environment of the South Caucasus. The participants also outlined several specific goals in information sharing and community building to coordinate better the rapidly proliferating group of scholars conducting survey and excavation across all three republics. Additionally, the topic of how to promote GIS ethically and sustainably among local South Caucasus researchers and institutions received intense scrutiny.

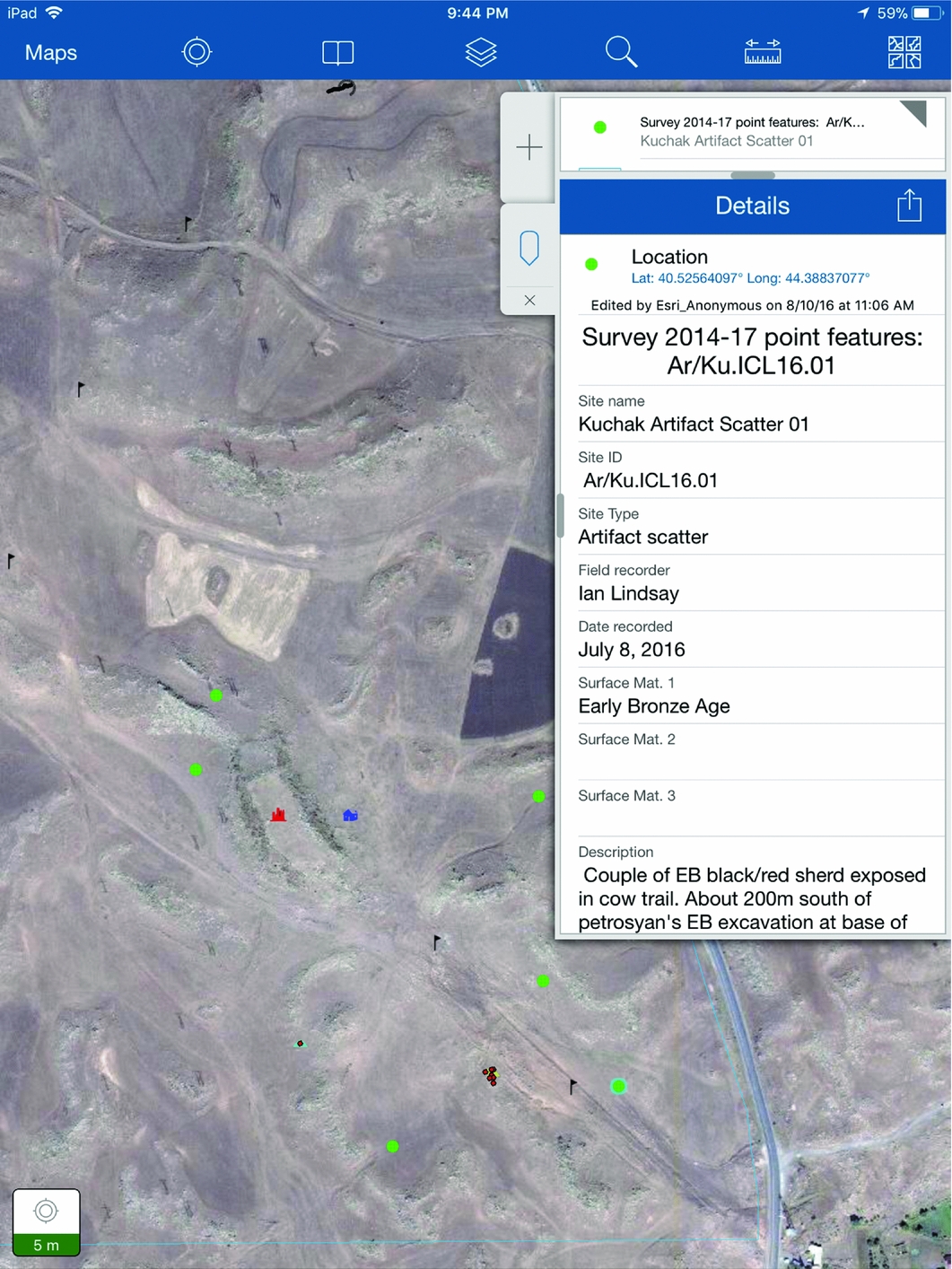

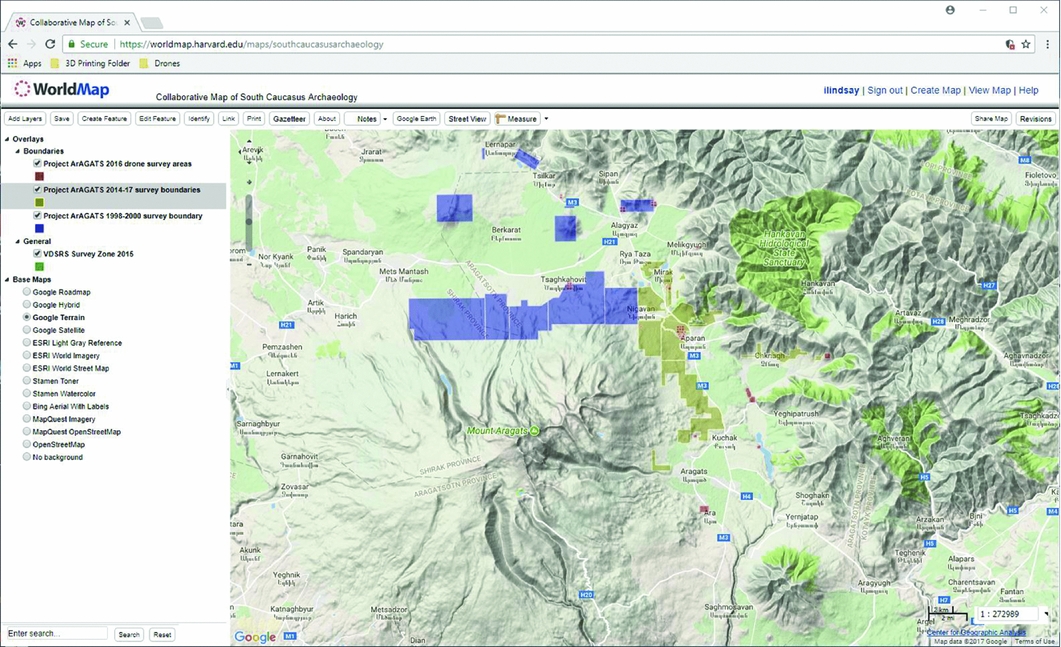

The workshop commenced with presentations on recent GIS, remote sensing and surface survey across the region. These illuminated the range of GIS applications deployed in regional research programmes, and presented issues of significant theoretical debate regarding landscape archaeology in the South Caucasus more generally. In particular, differences in long-term land use and transformation, ground cover history and geomorphology have meant that established strategies of remote-sensing use, pedestrian survey and sub-surface testing carried out in canonical Mediterranean and Near Eastern modes (e.g. Cherry et al. Reference Cherry, Davis and Mantzourani1991; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2003) deserve significant reconsideration as methods for studying South Caucasian landscapes. In many parts of the South Caucasus, for example, heavily contoured landscapes—altered by Soviet and post-Soviet land-use practices that have obscured or altogether removed surface artefacts—require more complex methods of investigation than basic satellite-imagery analysis, surface collection and ground-truthing (Figures 1 & 2). Discussions of project-specific solutions to the collection and analysis of spatial data in the heterogeneous Caucasian landscapes gave way to broad agreement that common platforms and protocols for collecting and sharing GIS-oriented information are now critical for supporting the continued growth of international archaeological research in the region (Figures 3–5). The escalating scale and intensity of research by collaborations of Western and local scholars over the last 15 years has resulted in a tremendous accumulation of satellite imagery, aerial photography, site geolocation and spatial analyses. In order to promote data sharing and prevent duplication of effort across projects, the participants agreed to pursue three primary efforts: 1) establish an online discussion board for GIS practitioners working in the South Caucasus region, hosted by the American Research Institute of the South Caucasus website (see http://arisc.org/?page_id=4258); 2) create a space on Harvard University's ‘World Map’ platform (Guan et al. Reference Guan, Boi, Lewis, Bertrand, Berman and Blossom2012) for sharing ‘spatial bibliographies’ of research, including GIS data (e.g. site locations, surveyed areas), remotely sensed imagery (footprints of acquired satellite data, aerial photography and photogrammetry), and their associated metadata (Figure 6; see https://worldmap.harvard.edu/maps/8294); and 3) outline the framework for a skills exchange workshop with an associated training session in the South Caucasus, to be co-taught by local and foreign GIS practitioners within the social science and humanities disciplines.

Figure 1. Ian Lindsay and Alan Greene survey the topographically diverse highlands of northern Armenia, overlooking the Pambak Range in the foreground, with the Tsaghkahovit Plain and snow-capped Mount Aragats in the southern distance. Such landscapes were heavily affected by Soviet land-reclamation and -amelioration programmes, thereby challenging traditional approaches to site survey and spatial data collection (photograph credit: Alan Greene).

Figure 2. Dan Lawrence records an ancient cistern on the Dariali Pass near Georgia's border with Russia, using QGIS open-source software installed on a Trimble Juno 3B handheld GPS (photograph credit: Dariali Pass Survey).

Figure 3. Emily Hammer and University of Chicago graduate student Teagan Wolter collect survey data to ArcPad installed on a Trimble Geo7X GPS, in the village of Nəhəçir, Azerbaijan, as part of the Naxçıvan Archaeological Project Survey (photograph credit: Eli Dollarhide).

Figure 4. Arshaluys Mkhrtchyan (Project ArAGATS), using Pix4D Collector application on an iPad Mini to program a flight mission for a Phantom 3 Pro drone in order to record a fortress site in the remote hills of the Tsaghkunyats Range, northern Armenia (photograph credit: Ian Lindsay).

Figure 5. iPad interface for the mobile GIS data collection system employed by Project ArAGATS in Armenia, using ESRI's Collector for ArcGIS application.

Figure 6. Screen capture of the ‘Collaborative Map of South Caucasus Archaeology’, powered by Harvard WorldMap and administered by the Humanities Mapping Lab at the University of Pennsylvania.

Finally, the ISAW workshop focused discussion on sensitive issues surrounding the promotion of GIS technology and research among scholars in the South Caucasus. While topographical mapping and GPS geolocation of archaeological sites have been common in the South Caucasus for some time, the use of desktop GIS and satellite remote sensing remains limited—partly by weak support for landscape approaches by local archaeologists, but more directly by the high costs of licensing and support for proprietary GIS software and its hardware requirements. Given the struggling economies of many newly independent states in the post-Soviet sphere, this raised the ethical concern of committing underfunded institutions to sets of GIS workflows that necessitate long-term investments in hardware and software maintenance. Instead of transplanting ‘Western’ methods and workflows, alternative strategies of local technological accommodation over top-down ‘implementation’ schemes were found by participants to be most appealing. In this sense, open-source GIS suites, such as QGIS, R or GRASS, carry distinct advantages, especially if they can be configured for use on open smart phone or tablet platforms. Strategies for the promotion of GIS training and usage have a much better chance for long-term growth if they are carried out with the locally available device market in mind.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the generous financial support of ISAW and ARISC for sponsoring this workshop, and for ISAW and its staff for providing the facilities. We also wish to thank each of the participants for their intellectual contributions to the workshop and for their commitment to advancing archaeological scholarship in the South Caucasus.