Over the past few decades, Iran has frequently been considered the connecting bridge between South-western, South-eastern, Central and Eastern Asia, and a significant migration path for Pleistocene human dispersals (Bar-Yosef Reference Bar-Yosef1994; Biglari & Shidrang Reference Biglari and Shidrang2006; Vahdati Nasab et al. Reference Vahdati Nasab, Clark and Torkamandi2013). Most studies of Palaeolithic Iran have been carried out by foreign archaeologists, and have concentrated on the Central Zagros (e.g. Braidwood et al. Reference Braidwood, How and Reed1961; Hole & Flannery Reference Hole and Flannery1967; Mortensen Reference Mortensen, Olsweski and Dibble1993). Although Iranian archaeologists (e.g. Biglari et al. Reference Biglari, Nokandeh and Heydari Guran2000; Roustaei et al. Reference Roustaei, Vahdati Nasab, Biglari, Heydari, Clark and Lindly2004) have followed the same trend in recent decades, there are still unknown prehistoric sites throughout this region. The Seimarreh Valley is one of the least known regions of the Central Zagros, particularly in terms of prehistoric archaeology; compared to other regions, such as Mahidasht and Chamchal, the Seimarreh Valley has been mostly neglected. A survey of the Valley by Zeynivand in 2011 identified a complex of caves and rockshelters containing Palaeolithic artefacts. Consequently, more sites were identified in 2015 after a new approach to surveying was adopted. This provided new data indicating the importance of the Seimarreh Valley during the Pleistocene era.

Geography and archaeological background

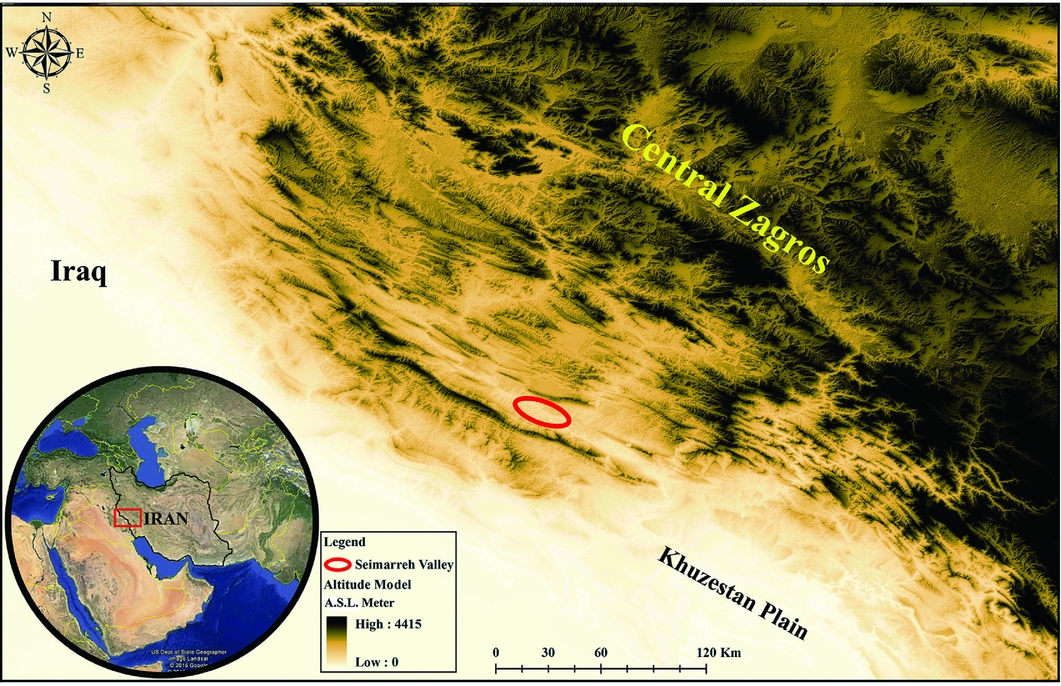

The Seimarreh Valley is located in central Darre-Shahr County, in Ilam Province. The strategic location of the area as the connecting link between the Central Zagros, Mesopotamia and the Khuzistan Plain (Figure 1) has played a major role in interregional cultural exchanges. Furthermore, environmental resources, such as an abundant water supply (e.g. the Seimarreh River), and the existence of natural fortifications (e.g. the Kabirkuh and Mahle Mountains) (Figure 2) have attracted various human groups throughout history and prehistory. Following survey work in 2010, Zeynivand (Reference Zeynivand2013) reported the first evidence for Pleistocene human activity in this valley. This initiated Palaeolithic studies in the region, and was followed by further survey in 2015.

Figure 1. Geographic location of the Seimarreh Valley (GIS map by Saeid Bahramiyan).

Figure 2. Map of Seimarreh Valley and distribution of Palaeolithic sites (GIS map by Saeid Bahramiyan).

Survey and landscape

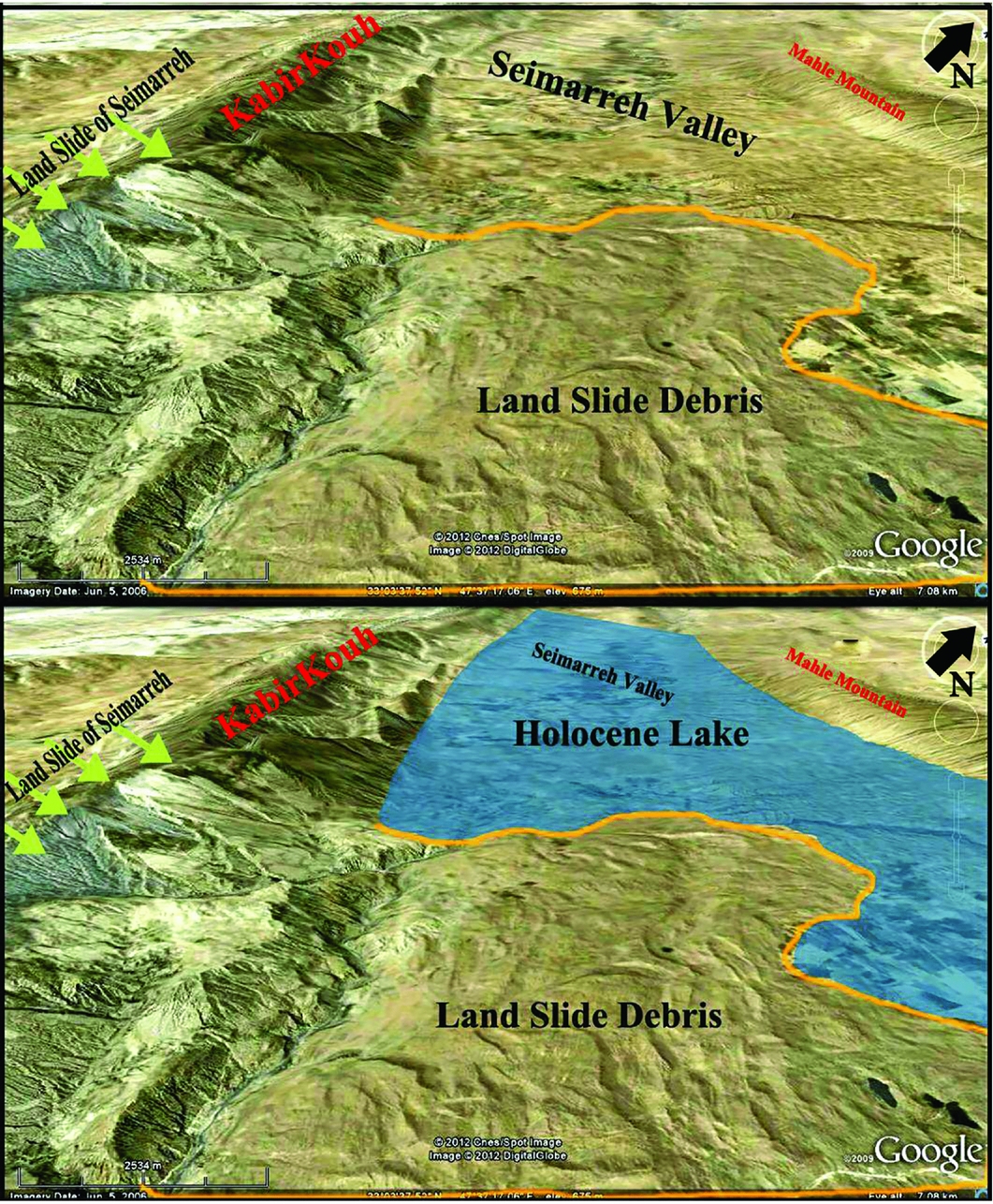

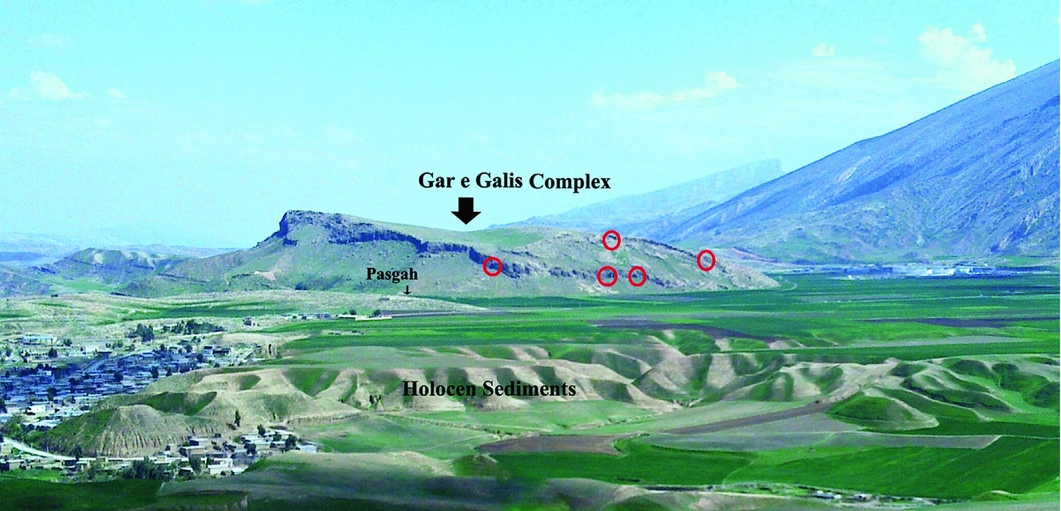

Our priority before beginning the 2015 survey was to form a competent and reliable understanding of the Valley's landscape and topography, combined with an examination of the extant archaeological and geological literature covering the area. Geological studies record a remarkably large landslide, which occurred during the early Holocene in the western part of Seimarreh Valley and on the eastern side of Kabirkuh. Known as ‘The Great Landslide of Seimarreh’, it is considered to be one of the world's biggest landslides (Harrison Reference Harrison1946: 62; Oberlander Reference Oberlander1965; Roberts Reference Roberts2008: 6). Its debris blocked the course of the Seimarreh and Kashkan Rivers in the north-eastern part of Kabirkuh and formed a natural dam and the subsequent great lake of Seimarreh. This submerged major parts of the Valley (Ambraseys & Melville Reference Ambraseys and Melville1982; Roberts Reference Roberts2008; Shoaei Reference Shoaei2014) (Figure 3). Eventually, the rivers broke through the dam and the lake was drained, leaving behind accumulated alluvial deposits. Due to the depth of this alluvium, the areas of the Valley with higher elevations have received more research attention. The 2015 survey discovered a number of Palaeolithic sites located at an altitude of 650–770m asl and higher than the current valley's ground surface (Figure 4). These sites include the Kal-Esbi rockshelter, the Gar-e-Alisafar and Pasgah open-space sites, and the Gar-e-Galis complex. The latter (Figure 5), comprising two caves and three rock shelters, is the most important site as an integrated complex based on the closeness of the sites and morphological and technological similarity of the artefacts.

Figure 3. Top: location and direction of the landslide (green arrows); bottom: formation of natural dam.

Figure 4. Histogram of Seimarreh Valley elevations and altitude of Palaeolithic sites.

Figure 5. View of the Gar-e-Galis complex and the landscape of Seimarreh Valley, looking north (photograph by Mohsen Zeynivand).

Artefacts

Most of the recovered artefacts are from the Gar-e-Galis complex (61 pieces) and Gar-e-Alisafar (37 pieces), while Kal-Esbi and Gar-e-Pasgah yielded 25 fragments of stone tools. All of the discovered Palaeolithic sites in the Seimarreh Valley contained flake/blade cores and bladelet cores, debris, debitage (unused blanks) and tools. In rare cases, the use of the Levallois technique has been recorded. The tools vary between retouched pieces, scrapers, notches/denticulates and borers (only 1 piece). Over 90 per cent of the debitage results from a flaking technique, which detached small flakes from the cores (Figure 6). Approximately 70 per cent of the debitage has plain and cortical platforms, revealing that the core had not been properly prepared for producing flakes, flake tools or microliths. The presence of notches and denticulates, scrapers, the use of the Levallois technique and the implementation of the flaking technique all suggest that the sites were occupied during the Middle Palaeolithic period. The presence of one perforator fragment and six blade and microlith pieces should not, however, be discounted. Given the dearth of Middle Palaeolithic evidence in the Zagros Moutains, such as double-sided and convergent scrapers or Mousterian points, or evidence from more recent periods, such as end-scrapers, burins, retouched blades and Dufour microliths, the chronology of the newly discovered Seimarreh Valley sites must be considered very cautiously.

Figure 6. Some of the collected artefacts: 1–2) cores; 3–5) blank flakes; 6) single side scraper; 7–8) alternate denticulates; 9) borer; 10–11) retouched small flakes; 12) bladelets (artefacts 6 & 7 show use of the Levallois technique; drawing by Saeid Zeynali).

Conclusion

Given the suitable environmental conditions and strategic geographic location of the Seimarreh Valley, it is surprising that no Palaeolithic site was found during two seasons of intensive survey. In 2015, however, a more precise survey based on geological studies confirmed evidence of a landslide, which had changed the morphology of the Seimarreh Valley and buried earlier sites under thick alluvial sediments. By focusing on areas higher than the current valley's ground surface, we discovered Palaeolithic occupation sites in rocky outcrops above the Holocene landslide deposits.