Towards objectscapes

The notion that archaeology is a discipline of ‘things’ (Olsen et al. Reference Olsen, Shanks, Webmoor and Witmore2012) is now a widely accepted theoretical position, advanced under headings such as ‘human-thing entanglement’ (Hodder Reference Hodder2012) or ‘material engagement theory’ (Malafouris Reference Malafouris2013). The essence of this position is that objects are more than the result of human intentions: they possess their own agency and are subjects in their own right. This idea was prominently developed by Gell (Reference Gell1998) into a method that can be tested (Van Eck Reference Van Eck2015). The precise nature of this non-human agency, however, is generating much debate, because things are not alive biologically. We follow Latour (Reference Latour1991)—who introduced the term actants for non-human agents—to make the fundamental point that both agents and actants ‘act’, and therefore possess agency.

This renewed attention to objects is often labelled ‘the material turn’ (Hicks Reference Hicks, Hicks and Beaudry2010). Despite extensive theoretical debate, it has proven difficult to put the material turn into practice (Antczak & Beaudry Reference Antczak and Beaudry2019). To address the need for practical approaches that do justice to the impacts of objects on past societies, we introduce the concept of the objectscape. We argue that the plotting of object histories and their resonances allows for better understanding of past societies. Indeed, Hodder (Reference Hodder2019) has presented a theory on human evolution in these terms. Working from a similar perspective, our aims are less grand and more applied.

In the following discussion, we outline what an ‘objectscape’ is, exploring its relationships to other concepts and how objectscapes work in terms of connectivity, relationality and impact. We present examples from two regions at the end of the first millennium BC: southern Germany and northern Syria. This was a period of Eurasian history that was characterised by a remarkable “excitation of the object world” (Gosden Reference Gosden2005: 208), and is thus ideal for illustrating the potential of thinking through objectscapes.

What is an objectscape?

An objectscape refers to the material and stylistic properties of a repertoire of objects in a given period and geographic range (Versluys Reference Versluys, Van Oyen and Pitts2017a; Pitts Reference Pitts2019: 7–19). Unlike the archaeological notion of the assemblage, which consists of a discrete, quantifiable and static group of objects that share an archaeological context, an objectscape comprises a dynamic repertoire of objects in motion (Versluys Reference Versluys2014, Reference Versluys, Van Oyen and Pitts2017a). Some elements of this repertoire may be more locally distributed (e.g. coarseware pottery), with other elements circulating more widely and featuring greater volatility in their contextual configurations (e.g. fineware pottery and silver plate). Whereas ‘assemblage’ is commonly used to denote intra-site artefact configurations, ‘objectscape’ is better suited to working with more expansive and fluid conglomerations of objects, at the scales of whole sites, periods and regions. An objectscape therefore maps a portion of space-time.

Studying objectscapes entails putting the relationality of material culture at the centre of analysis, enabling a new kind of history conceived in terms of human-thing entanglements, and moving from comparisons of static assemblages to cultural dynamics. This requires objects to be understood in terms of their contexts and associations (as assemblages), but also how they came to be constituted (i.e. their genealogy) and their subsequent trajectories, in time and space, by comparing their impacts at a variety of analytical scales. Objectscapes are analogous to the idea of ‘relational constellations’ (Van Oyen Reference Van Oyen2016), which has been used to highlight different kinds of relationality operating within discrete categories of objects. In contrast, objectscapes may also be used to investigate relationality in contextually determined conglomerations of things, emphasising relations both within and between object categories. Privileging relationality fosters better understanding of what objects did in the past, and confronts the assumptions inherent in many studies in which objects are reduced to proxies for abstract processes (e.g. economic growth) or social categories (e.g. ethnicities and identities) (Van Oyen & Pitts Reference Pitts and Hodos2017). We believe that this is especially relevant to globalising scenarios, in which societies are suddenly exposed to larger and denser networks of people and things moving in ever-greater numbers and frequency.

Objectscapes are related to the idea of visual and material koine, which emphasises shared vocabularies (Versluys Reference Versluys, Pitts and Versluys2015). Although this term originated in literary studies, it is valuable when understood in terms of the transformation and creative appropriation of objects by people with a variety of motivations embedded within their local habitus (Dietler Reference Dietler, Handberg and Gadolou2017). Indeed, by prioritising relationality within a koine of things, the notion of objectscapes allows the phenomenon of standardised styles, designs and objects to be understood as having impacts through their particularisation in specific historical contexts. With objectscapes, however, the focus is not on the strategies of the human bricoleurs, but rather on the repertoire's local impact through its genealogy, and how this genealogy has an important role in conditioning an object's subsequent trajectories. There is a similar difference in the emphasis between objectscapes and the ideas of ‘communities of style’ (Feldman Reference Feldman2014) and ‘communities of practice’ (Wenger Reference Wenger1998). We argue that objectscapes better challenge the representational assumptions concerning objects that are inherent in focusing on human communities. What these ideas have in common is that repertoires of objects have close relationships with, and can influence, societal formation.

Being conscious of the risks of adding another ‘scape’ to the archaeological toolbox, we re-state our intention that the notion of objectscapes should be used to help put the material turn into practice within archaeology. It is not a theoretical innovation in itself, as the body of theory already exists. This becomes clear when considering the relationship between objectscapes and other ‘scapes’ used in archaeology. We suggest that discussions on the phenomenology or biography of landscape (Kolen et al. Reference Kolen, Renes and Hermans2015) and the use of neologisms such as seascape, islandscape, plantscape or cityscape (Berg Reference Berg, Antoniadou and Pace2007; Frieman Reference Frieman2008; Farahani et al. Reference Farahani, Chiou, Harkey, Hastorf, Lentz and Sheets2017; Mania & Trümper Reference Mania and Trümper2018) essentially serve the same purpose: to draw attention to the reality that these are not pristine (ecological) entities waiting to be altered by human agency. Rather, they are constitutive factors that shape human action, society and history through their affordances—especially over the long term (Gosden Reference Gosden, Tilley, Keane, Küchler, Rowlands and Spyer2006).

These other ‘scapes’ emphasise the constructive role of the (natural) environment in the human story, and it is in this sense that they are related to objectscapes. Objectscapes, however, more closely resemble the concepts of taskscape and ethnoscape, formulated by Ingold (Reference Ingold1993) and Appadurai (Reference Appadurai1990) respectively. A taskscape refers to the collective ensemble of actions that an individual, community or society performs, emphasising the interlocking nature of such tasks in terms of emergent causation. Similarly, an objectscape is the collective ensemble of objects available for an individual, community or society, emphasising emergent causation through its interlocking relations with humans. Whereas taskscape and objectscape overlap in their focus on emergence, ethnoscape and objectscape overlap in their foregrounding of flows. Appadurai (Reference Appadurai1990) introduced the notion of ethnoscape to underline that, at a time of intense connectivity, familiar anthropological objects should no longer be understood as spatially bounded, historically unconscious and culturally homogeneous. Likewise, we argue that archaeological objects can no longer be understood as spatially bounded, historically unconscious (hence our focus on genealogy) and culturally homogeneous, especially when globalising forces are at play.

How objectscapes work

The archaeological investigation of objectscapes revolves around asking four practical questions of a particular period and geographic range: what objects, styles and materialities are new? Where do they come from? How do they innovate? And what are the historical consequences of these material changes? With these questions in mind, we now consider how objectscapes work and the main parameters for their investigation: the interconnected principles of connectivity, relationality and impact.

Connectivity is important for answering our first two questions concerning novelty and provenance, as changes in objectscapes often come about through the impacts of moving objects, their styles and materialities. Exposure to intensifying connectivity entails new encounters with objects in motion, effectively enlarging the inter-artefactual domain (see below). In the shorter term, this often results in more stylistically and materially diverse objectscapes, with new kinds of objects increasing the range of possibilities for local cultural production. The maintenance of a connected milieu in the longer term can forge loosely shared, pan-regional repertoires of objects and styles, as a globalising koine that is susceptible to local particularisation. Taking objectscapes seriously also requires us to consider ebbs in connectivity and obstacles to object-flows, which, in turn, may result in innovative or otherwise distinctive configurations of material culture.

Relationality matters because objects are always part of an inter-artefactual domain. This concept was introduced by Gell (Reference Gell1998) to emphasise the relationality between the stylistic universes of existing and new objects. In the inter-artefactual domain, the predominant factor governing the appearance of objects is their relationship to extant artefacts (Gell Reference Gell1998: 216). In practical terms, this helps to explain why artefacts that are part of the same koine or connected milieu look similar and share stylistic features. The workings of the inter-artefactual domain are most evident within distinct classes of objects, with change driven by the ‘principle of least difference’, whereby new objects are created involving minimal alteration to extant examples (Gosden Reference Gosden2005: 203), and influences across styles and materials being commonplace (e.g. skeuomorphism). The concept also helps to explain repetitive elements in the configurations of discrete assemblages, from the architectural features of a building (Gell Reference Gell1998: 255) to the objects placed in a grave. In this way, the inter-artefactual domain is a keystone concept that provides a bottom-up perspective on conglomerations of artefacts that form the building blocks of objectscapes.

Impact is central to understanding objectscapes as immersive groups of actants that affect people, other objects and cultural dynamics. It is at the heart of addressing our third and fourth questions on how objects innovate, and the socio-historical consequences of material changes. The possibilities for impacts within objectscapes can be charted along the axes of space and time: the impact of objects in motion should not be limited to discussions of connectivity. Novel objects can have impacts in the short term, for instance, through mobilisation for social display and association with local prestige objects; in the medium term through deliberate local replication, imitation or influence; and in the long term through gradual appropriation and subconscious embedding in the habitus. The mass availability of Chinese porcelain in Europe from c. AD 1600 provides a useful example (Pitts Reference Pitts and Hodos2017). In the short term, ‘china-mania’ took hold as a result of the distinct material qualities of porcelain, which were beyond the technical capabilities of European producers to replicate. In the medium term, impacts can be seen in local efforts to imitate Chinese porcelain, culminating in the development of European porcelain industries, the spread of Chinese décor (stylistics) to other materials and media (chinoiserie), and new social practices (tea/coffee drinking) that depended on porcelain. Lastly, the long-term impact of Chinese porcelain in Europe is most profoundly evidenced in the globally ubiquitous everyday plates and cups that have become naturalised in the lives of billions throughout the modern world.

A major chronological dimension to impact experienced within objectscapes concerns genealogy, which helps us to deal with the legacy of history (Gosden Reference Gosden2005: 203). An object's genealogy can be understood as the embodiment of its design heritage, in terms of both materials and stylistics. Impact relating to an object's genealogy depends on differential knowledge of this heritage and its associations by producers, users and viewers (Appadurai Reference Appadurai1986: 41–56). The impacts of object genealogies are often evident in single object repertoires with multiple design lineages. Chinese porcelain circulating in Europe in the seventeenth century, for example, included designs with both European and Asian genealogy, which often had a major bearing on the use-trajectories of different vessels. Whereas ‘un-Chinese’ types like klapmutsen (hat-shaped soup bowls) were popular in the Netherlands due to their capacity to accommodate a resting metal spoon and therefore fit with local eating practices, Asian forms such as gourds and kendis had less obvious practical use. The latter were more likely to end up as display pieces in aristocratic collections, in which Asian style evoked European cultural connotations of China (Rinaldi Reference Rinaldi1989).

Changing objectscapes at the Rhine-Moselle-Saar nexus: selections of things en masse

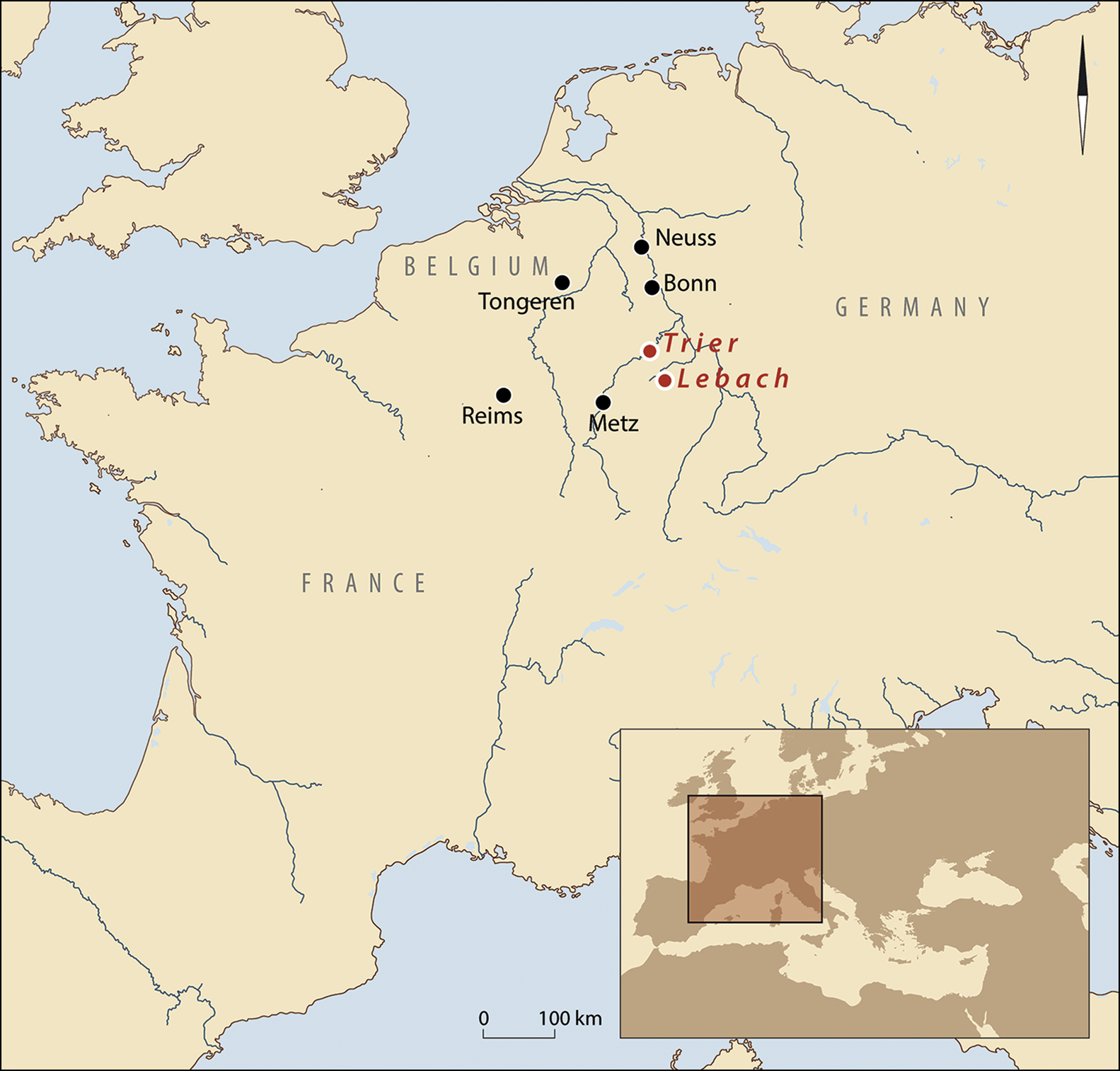

Our first case-study concerns the Iron Age to Roman period in North-west Europe. To illustrate what is at stake by thinking through objectscapes, we compare two cremation burials from southern Germany at the end of the first century BC—roughly 50 years after Julius Caesar's conquests again brought the region into closer contact with the Mediterranean world. One grave was located near the newly founded city of Trier (Augusta Treverorum), the tribal centre of the Treveri. The other is from Lebach (Saarland), a cemetery with pre-Roman origins over 40km to the south of Trier (Figure 1). While age and sex data are lacking for the cremated human remains, the rites apparent for both graves are consistent with those of communities across the region.

Figure 1. The early Roman Rhine-Moselle-Saar nexus (figure by J.F. Porck).

Let us start by considering the novel associated objects and their genealogies. The graves’ contents (Figure 2) testify to a sudden ‘object revolution’ in the last decades of the first century BC, a time of increased volume and variety of things in circulation (Pitts Reference Pitts2019). Most of the object designs within the graves are entirely new. Indeed, the only artefacts consistent with pre-Roman assemblages are the sword and spearhead (at Lebach), and a single handmade pottery vessel in each grave. Of the novel elements, only the red-gloss terra sigillata platter (at Trier) might suggest a connection with Italy, reflecting the scarcity of such wares in northern Gaul other than at military bases, before large-scale production commenced in southern Gaul in later decades (Pitts Reference Pitts2019: 67–82). Nevertheless, terra sigillata had a profound contemporary impact. This is evident in the graves in the form of regionally produced terra rubra vessels, which closely imitated sigillata designs in both morphology and colour (Deru Reference Deru1996: types A4 and C8). Notably, these vessels are among the first truly standardised objects mass-produced in this part of North-west Europe.

Figure 2. Finds from Trier: top) Valeriusstrasse (St Matthias) grave 1928 (after Goethert-Polaschek Reference Goethert-Polaschek and Trier1984: 209–16); bottom) Lebach grave 106 (after Gerlach Reference Gerlach1976: figs 74–75).

While such ‘Gallo-Belgic’ ware production began at fledgling cities such as Reims and Trier to supplement military supplies of sigillata, its distribution eventually became more prevalent in civilian society. Around half the designs in the Gallo-Belgic repertoire had Northern European genealogies, rather than imitating Mediterranean designs in sigillata. Whereas vessels with Mediterranean genealogy had universal distributions and were more common at military bases and cities, those with Gallic genealogy had more regionally rooted distributions and were more prevalent at locations linked with indigenous communities. Of the latter, the most common were capacious beakers. These were present in both graves as grey-black terra nigra butt-beakers (Deru Reference Deru1996: types P1 and P8) and a Grätenbecher (P23) at Trier. These specific types of butt-beakers, along with the copper-alloy Kragenfibel brooches (at Trier), had localised distributions in Treveran territory, but were genealogically related to beakers and fibulae with pan-regional circulations (Pitts Reference Pitts2019: 63–110).

To answer questions concerning the innovation and historical consequences of this novel proliferation of objects, we now consider connectivity and relationality in the grave ensembles. The Trier grave yielded a larger assemblage, with most selections at face value resonating with a connected Roman urban environment: a terra sigillata plate, a terra rubra plate, a set of five terra rubra cups in two standard sizes and a flagon—all new designs with Mediterranean genealogy. This image must, however, be reconciled with the jarring inclusion of two large beakers with Gallic genealogy, a pair of fibulae and a handmade bowl. These objects seemingly refer to pre-Roman traditions and objectscapes. Large drinking vessels were prevalent in Late Iron Age funerary assemblages across the region, and emphasise the social importance of alcohol consumption in communal feasting (Pitts Reference Pitts2019: 41). Indeed, the regional theme of Iron Age commensal hospitality is also implicated in the set of five cups—despite their Mediterranean designs—hinting at the continued importance of providing multiple place-settings for guests at feasts. While extensive sets of identical vessels are frequently a hallmark of pre-Roman aristocratic graves, they are virtually absent in contemporaneous cemeteries used by Roman military personnel and veterans, whose grave-repertoires emphasise objects for individual use alone.

In contrast, the objects in the grave from the cemetery of Lebach present a very different picture. Most conspicuous is the inclusion of a sword and spear—a common practice in Late Iron Age cemeteries of the region, albeit one that declined markedly following Roman conquest (Pitts Reference Pitts2019: 78–82). An older handmade jar and terra nigra butt-beaker further emphasise a sense of regional conservatism. After all, the cemetery at Lebach was not particularly close to any major cities or hubs; traditional objectscapes therefore exert greater influence. In this context, the standardised terra rubra plate (A4) and cup (C8) with Mediterranean genealogies are strikingly incongruous and innovative. The deliberate inclusion of these vessels speaks to connectivity, but just as important was the decision to opt-in to a novel practice of object selection and deposition that was being replicated across a much wider region (and was also seen at Trier with identical pottery types). Indeed, the deliberate selection of regionally distinct butt-beakers, standardised Gallo-Belgic cups and plates, and intrinsically local objects (e.g. the handmade pottery) in both grave assemblages heralds the emergence of an increasingly pan-regional cultural logic that acted to unite societies with pre-Roman origins across a wide area. Such a practice even encompassed societies outside the Roman Empire (at that time), such as in southern Britain (Pitts Reference Pitts2019).

Where does the agency lie in the selection of grave inclusions in the different social contexts of Trier and Lebach? Thinking through objectscapes draws our attention to the relationality in the configurations of objects in both graves—namely the presence of standardised objects with Mediterranean genealogy and the enduring agency of later Iron Age material practices. The strength of these shared logics was such that they were replicated in thousands of graves across diverse societies in North-west Europe, in a manner barely witnessed in the preceding era (Pitts Reference Pitts2019). This perspective helps us to understand how some object selections at relatively disconnected Lebach were dependent on pan-regional frames of reference, and those at super-connected Augusta Treverorum retained considerable influence from later Iron Age objectscapes. The many human decisions behind these patterns were made not in isolation, but rather were informed by the circulation of striking new objects and styles, and simultaneously affected by memories of objects that were used in past funerals. Furthermore, by enacting their choices, the buriers inadvertently made incremental contributions to an evolving, inter-artefactual domain comprised of objects with distinct histories and genealogies, moving, replicating and innovating at different velocities and intensities.

By privileging objectscapes, a new kind of narrative emerges, in which the agency of the traditional players is put into perspective, such as the Roman state, and configurations of people and things take centre-stage. This is not to say that the Roman state did not exert considerable influence on objectscapes, as seen through the state-sponsored supply networks in which military bases and urban centres received greater quantities of various standardised artefacts. But there are limits to this logic. The state could not exercise absolute control over the plethora of biographical pathways of itinerant objects in motion, and that was certainly not its intention. Similarly, framing material practices in purely ideological terms of imperialism and its discontents (Romanitas vs resistance) significantly constrains the possibilities for understanding the complexities of object and human agency. In contrast, approaching the formative period of the later first century BC in terms of objectscapes encourages ideologically driven paradigms, like Romanisation, to be re-conceptualised in terms of the extension and merging of regional inter-artefactual domains, and the impacts of a proliferation of innovating standardised objects borne of new historical conditions of dramatically enhanced connectivity (Versluys Reference Versluys2014; Pitts & Versluys Reference Pitts and Versluys2015). It is no coincidence that novel object configurations emerging in this decisive globalising moment went on to exert considerable genealogical influence on objectscapes in North-west Europe for many centuries. Thinking through objectscapes helps to explain variability in material culture beyond the terms of human agency alone: “taking things seriously allows us to put people into perspective” (Woolf Reference Woolf, Van Oyen and Pitts2017: 216).

Changing objectscapes at the Euphrates: the impact of the crenellation motif

In antiquity, the region of Commagene in the modern Turkish province of Adiyaman was considered part of northern Syria (Figure 3). Although there is a lack of detailed archaeological evidence for the first-millennium BC Assyrian, Achaemenid and early Hellenistic periods from this region, it is clear that from c. 100 BC there was an object boom, at least in terms of dynastic representation. Through monumental building projects of the Orontid Dynasty and its most pre-eminent king, Antiochos I (69–36 BC), the royal Commagenean objectscape changed tremendously (Riedel Reference Riedel2018). Recent interpretations of the ‘palace of Mithridates’, a large, monumental structure in the capital city, Samosata, encourage us to think in terms of a ‘consumer revolution’ within elite contexts. Antiochos I presented his dynasty, through material culture and its stylistics, as the central node in a global Eurasian network (Versluys Reference Versluys2017b). Many of the Late Hellenistic objects that we encounter seem novel to the region as a result of this globalising moment.

Figure 3. The Late Hellenistic kingdom of Commagene at the Euphrates in northern Syria (figure by J.F. Porck).

To answer our four questions formulated above, we address one particular novelty of the Antiochan objectscape: the ‘crenellation motif’. This was a decorative element found in mosaics from the palace at Samosata and the so-called ‘banqueting rooms’ at nearby Arsemeia ad Nymphaeum (Lavin Reference Lavin and Dörner1963). Functioning as a decorative border, the motif consists of ‘turrets’, with three merlons on top and a pair of crenels in between, commonly executed in contrasting dark and light colours and interlocking in a band (Figure 4). Crenellation motifs featured in both mosaics and paintings. Although occurring infrequently, examples of the latter are found from Crimea to Etruria to Egypt from the third and second centuries BC (Brown Reference Brown1957). These paintings were often used to decorate the ceilings of tombs in imitation of textiles (Andreae Reference Andreae2012: 36). The mosaic examples date from c. 200 BC–AD 200, and are most prevalent from c. 100 BC onwards. Around 60 mosaics featuring the motif are documented, with Commagene providing the easternmost known example (Zschätzsch Reference Zschätzsch and Mastrocinque2009). The earliest crenellation in mosaics comes from Italy, Alexandria, the Peloponnese and Pergamon. This wide geographic distribution suggests that the crenellation motif was a global phenomenon from its very beginnings. When the mosaics with crenellation were selected for the Samosata palace and the rooms at Arsameia ad Nymphaeum, at c. 50 BC, they were, however, novel to Commagene and the wider region.

Figure 4. The crenellation motif from the so-called ‘banqueting rooms’ at Arsemeia ad Nymphaeum (centre; reproduced with permission of Forschungsstelle Asia Minor, Münster), and reconstructed from mosaics at the palace at Samosata (bottom and right, by L. Kruijer & J.F. Porck).

Mosaics featuring crenellation constituted a radical change to the objectscape of Commagene, significantly altering styles of consumption in a palatial context. To understand these changes in terms of social practice and to investigate what the crenellation motif did in Samosata, we must consider the relational properties of this standardised object-motif in a connected milieu. The genealogy of the crenellation motif and its earlier impact across different vistas of time and space are key to understanding these relational properties.

On a local scale, the crenellation mosaics constructed a visual coherence between the dynastic contexts of Samosata and Arsemeia ad Nymphaeum. As patron of both contexts, Antiochos I developed a dynastic programme of self-presentation and legitimation that was characterised by recurring elements distributed widely across his kingdom (Versluys Reference Versluys2017b). The crenellation mosaics were involved in this attempt at coherence and canonisation—qualities probably strengthened by repetition in the motif itself. The crenellation motif played a role in a global Hellenistic network, and its ‘consumption’ in Commagene thus implies the joining of the network, in its own particular way.

Contemporaneous examples from Thmuis (Egypt), Pergamon, Arkadia and Delos show that the motif was reserved for highly prestigious contexts, and used in an especially decorative manner (for these examples, see the catalogue published in Zschätzsch Reference Zschätzsch and Mastrocinque2009). These decorative norms and concepts were respected in Commagene, implying that the global meaning of the motif formed part of its impact in Samosata. From a local perspective, the impact of the crenellation mosaic can be located in the sphere of dynastic authority. From a global perspective, however, its agency involved situating the palace amongst a rarefied group of prestigious, awe-inspiring contexts from the Hellenistic world. The impact of crenellation mosaics on a regional scale was also located in their exclusiveness and novelty. Although the evidence is limited, crenellation is absent from contemporaneous regional mosaics, such as the floor decoration of palaces at Jebel Khalid or Dura Europos (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Connor, Crewe, Frohlich, Jackson, Littleton, Nixon, O'Hea and Steele2002). While comparable in opulence, these contexts did not opt for mosaic floor decorations, but probably had their floors decorated with tapestries, as was common in the Central Asian Oriental tradition. From a regional perspective, the materiality of the mosaic motif further enhanced the affordances of exclusivity and novelty. The impact of the crenellation mosaic in Samosata was located in the fact that it was globally developed, regionally exceptional and locally repeatable.

Let us now consider the genealogy of the crenellation motif. For Republican Italy, crenellation was seemingly used to indicate architectural fortifications (Salvetti Reference Salvetti2016). This was a Roman invention of c. 100 BC, as the motif originally referred to the textile ceiling drapery of tombs (see above). This affordance of the motif may have constituted part of its impact in Samosata, as Hellenistic kings also liked to present themselves as city founders and fortification builders (Ma Reference Ma and Erskine2003). Other possible affordances of the mosaic relate to its imitation of carpets. Although textile production was probably important in Commagene, no examples survive from the kingdom. Comparanda from other Hellenistic sites suggest that their concentric border decoration shared visual similarities with the crenellation band seen on the Samosata mosaics. As such, it is possible that the Samosata mosaics referred to the carpets that decorated the floor of royal palaces in the wider region—especially to the east of the Euphrates. If so, this would constitute a remarkable (material) innovation of that tradition. More specifically, in the Late Hellenistic world, luxury carpets were associated with the Achaemenid court as a form of Persianism; that is, as an attempt to buy into the prestige that the memory of the Achaemenid Empire held across Asia (Strootman & Versluys Reference Strootman and Versluys2017). In sum, to explain the impact of the crenellation motif in objectscapes at Samosata, we must consider its genealogical associations intermingling and working together, as the innovative local particularisation of a globalising object-motif. Hence, a new picture of transformation emerges, beyond traditional notions such as ‘Hellenisation’ or ‘propaganda’, in which new configurations of people and things are central.

On the basis of elements such as the crenellation motif, the kingdom of Commagene has been described as ‘Hellenised’ by many scholars, who subsequently presuppose the influence of Greek ethnic or socio-cultural features (for a discussion of this view, see Versluys Reference Versluys2017b: 191–201). Thinking through objectscapes demonstrates the fundamental misconceptions of such an interpretation. The crenellation motif was not brought to Commagene by or for Greeks while spreading Hellenistic ideas. There is human agency in the local appropriation of this particular motif from a global repertoire. There is also object agency in what the motif achieves in Commagene through its specific genealogy and its relationality within the inter-artefactual domain. Hellenisation, therefore, denotes a specific period of Eurasian connectivity and its consequences for the changing functionalities of a rapidly globalising objectscape. What is Hellenistic about Hellenistic Commagene is this novel configuration of things and people. As with Romanisation, one could say that Hellenisation—as well as many other -isations of world history—are about understanding objects in motion (Versluys Reference Versluys2014). That is not to rule out the importance of human agency within human-thing entanglements, or to sanitise the past (contra Fernandez-Götz et al. Reference Fernández-Götz, Maschek and Roymans2020). Issues of dynastic power, for instance, played an important role with the crenellation motif, as we have seen. Thinking through objectscapes, however, puts such human agency into perspective, and provides us with a more complete picture of the past, as a cultural ecology (Woolf Reference Woolf, Van Oyen and Pitts2017).

Conclusions

In this article, we have introduced the notion of the objectscape as a practical tool for putting the material turn into practice in archaeology, with particular relevance to societies undergoing remarkable punctuations of connectivity (globalisation) (Pitts & Versluys Reference Pitts and Versluys2015). The examples discussed demonstrate the potential of investigating objectscapes to illuminate the impact of artefacts and visual styles at different intersections of the Afro-Eurasian network in the late first millennium BC. Comparing the case studies reveals the profound agency of standardised objects in motion that transformed objectscapes in distinct local ways, but anchored the societies in question at different ends of the richly complex, globalising cultural milieu of the Hellenistic–Roman era. The examples emphasise how the transformative power of connectivity is fundamentally channelled through objects in motion, with object genealogy providing a significant vector and marker of short- and long-term changes in objectscapes and their societies. Traditionally, the scenarios we describe have been framed as examples of ‘Hellenisation’ or ‘Romanisation’, and understood in terms of human agency. It is now time to re-evaluate these and many other historical phenomena through objectscapes: world history is as much about flows of objects as it is about people.

Acknowledgements

The crenellation case-study summarises aspects of the PhD research of Lennart Kruijer (Leiden), a member of the VICI project ‘Innovating objects: the impact of global connections and the formation of the Roman Empire’, directed by Miguel John Versluys. We thank Henry Bishop-Wright, Rebecca Henzel, Alasdair Gilmour, Karen Gregory, Lennart Kruijer, Suzan van de Velde and two anonymous peer-reviewers for their helpful feedback on the article drafts. Any errors remain our own.

Funding statement

Funding was received from The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) (VICI grant 277-61-001).