Crossref Citations

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by

Crossref.

Czerniak, Lech

Pędziszewska, Anna

Święta-Musznicka, Joanna

Goslar, Tomasz

Matuszewska, Agnieszka

Niska, Monika

Podlasiński, Marek

and

Tylmann, Wojciech

2023.

The Neolithic ceremonial centre at Nowe Objezierze (NW Poland) and its biography from the perspective of the palynological record.

Journal of Anthropological Archaeology,

Vol. 72,

Issue. ,

p.

101551.

Whittle, Alasdair

2024.

Kinship questions.

Documenta Praehistorica,

Vol. 51,

Issue. ,

p.

238.

Czerniak, Lech

Bayliss, Alex

Goslar, Tomasz

Badura, Monika

Budilová, Kristýna

Lisá, Lenka

Marciniak, Arkadiusz

Matuszewska, Agnieszka

Pędziszewska, Anna

and

Święty-Musznicka, Joanna

2024.

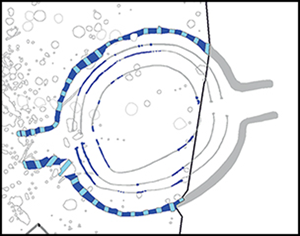

Monumental and Long-Lasting or Temporary and Performative? How did Neolithic Rondels Function? Radiocarbon Dating and Bayesian Chronological Modeling of the Rondel at Nowe Objezierze (Northwestern Poland).

Journal of Field Archaeology,

Vol. 49,

Issue. 5,

p.

335.

Šošić Klindžić, Rajna

Šiljeg, Bartul

and

Kalafatić, Hrvoje

2024.

Multiscale and Multitemporal Remote Sensing for Neolithic Settlement Detection and Protection—The Case of Gorjani, Croatia.

Remote Sensing,

Vol. 16,

Issue. 5,

p.

736.

Sobkowiak-Tabaka, Iwona

Gerasimenko, Natalia

Kurzawska, Aldona

Kufel-Diakowska, Bernadeta

Moskal-del Hoyo, Magdalena

Stróżyk, Mateusz

Rohozin, Yevhenii P.

Ridush, Bogdan

Levinzon, Yevhenii

Boltaniuk, Petro

Nechytailo, Pavlo

and

Diachenko, Aleksandr

2024.

Risks beyond the ditch: Copper Age tannery from the settlement of Kamianets-Podilskyi (Tatarysky), Ukraine.

Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences,

Vol. 16,

Issue. 4,

Czerniak, Lech

2025.

Construction, Maintenance and Ritual Practices on the Neolithic Rondel at Nowe Objezierze (Northwestern Poland): The chaîne opératoire of Rondel’s Architecture.

Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory,

Vol. 32,

Issue. 1,