In 2018, the Franco-Myanmar project ‘Thanintharyi and the Maritime Silk Roads’ carried out its first season of excavations at Maliwan and Aw Gyi in Myanmar's southernmost state, Thanintharyi. The project is a collaboration between the French National Centre for Scientific Research and the Myanmar Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture, and is supported by the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs.

The project aims to define the economic and political role that this region played in the first ‘trans-continental’ maritime exchange network, which linked the Western world to China from the third/fourth century BC. The research seeks to determine to what extent and in what manner long-distance exchange fashioned peninsular populations’ social, economic and political trajectories. The inception of this long-distance network took place during a period in which both Mauryan India and Han China became unified political entities. It inaugurated a trading boom and major social changes amongst the societies involved, including the spread of Buddhism, Indic political concepts and various types of material culture.

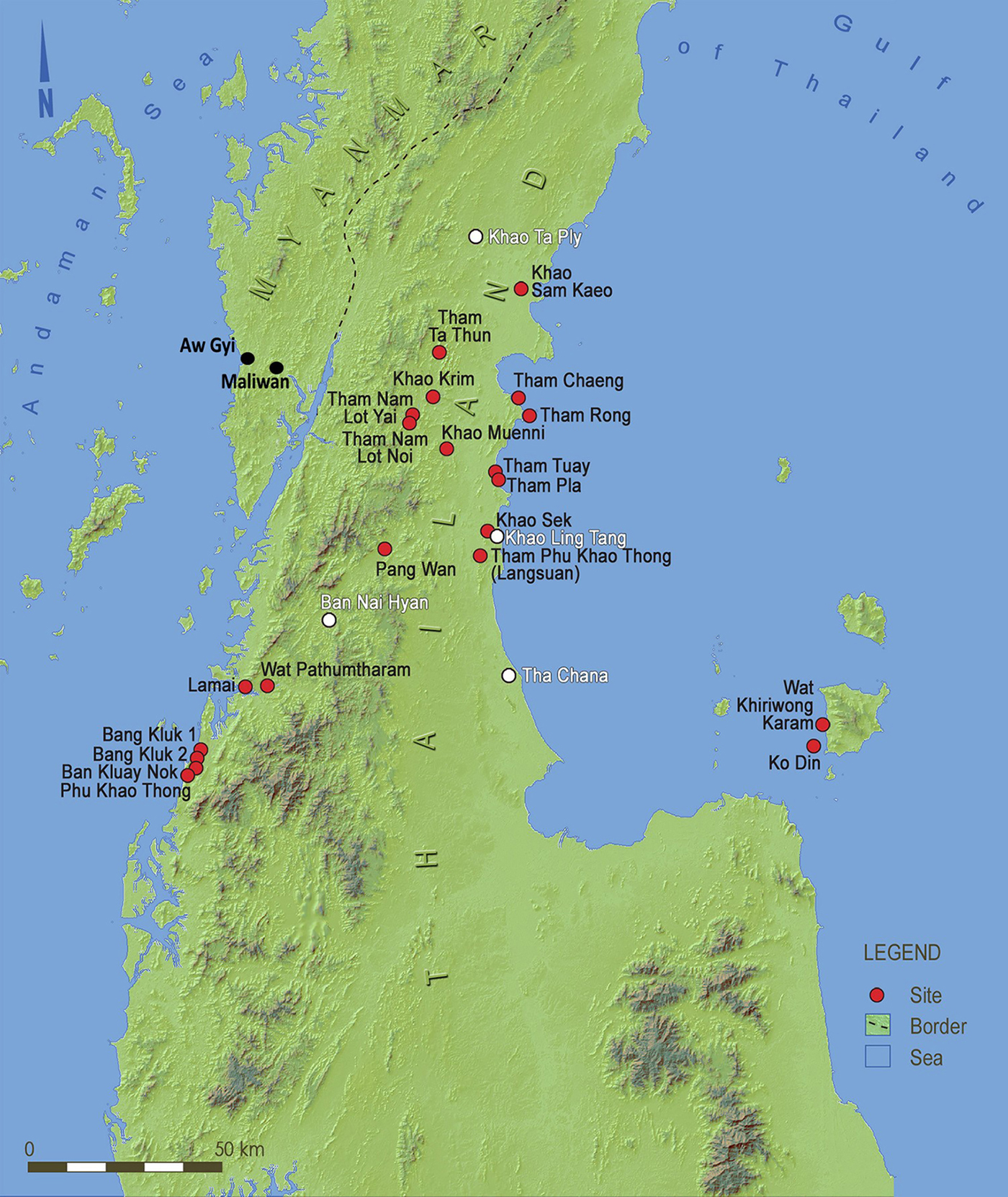

Figure 1. Map of the study area including key sites.

The Thai-Malay Peninsula, to which Thanintharyi belongs, acted as a central region in these exchanges, located between the Indian (Bay of Bengal) and Pacific (South China Sea) Oceans. From the last centuries BC, travellers and merchants sailing in these monsoonal waters made stopovers in one of the riverine ports along the Peninsula coast, where they could replenish their supplies, maintain their vessels, obtain local or imported goods stocked in local entrepôts and exchange ideas with other traders. Thus, the Peninsula became a hub and a cradle for innovations that were then redistributed in both the Bay of Bengal and the South China Sea.

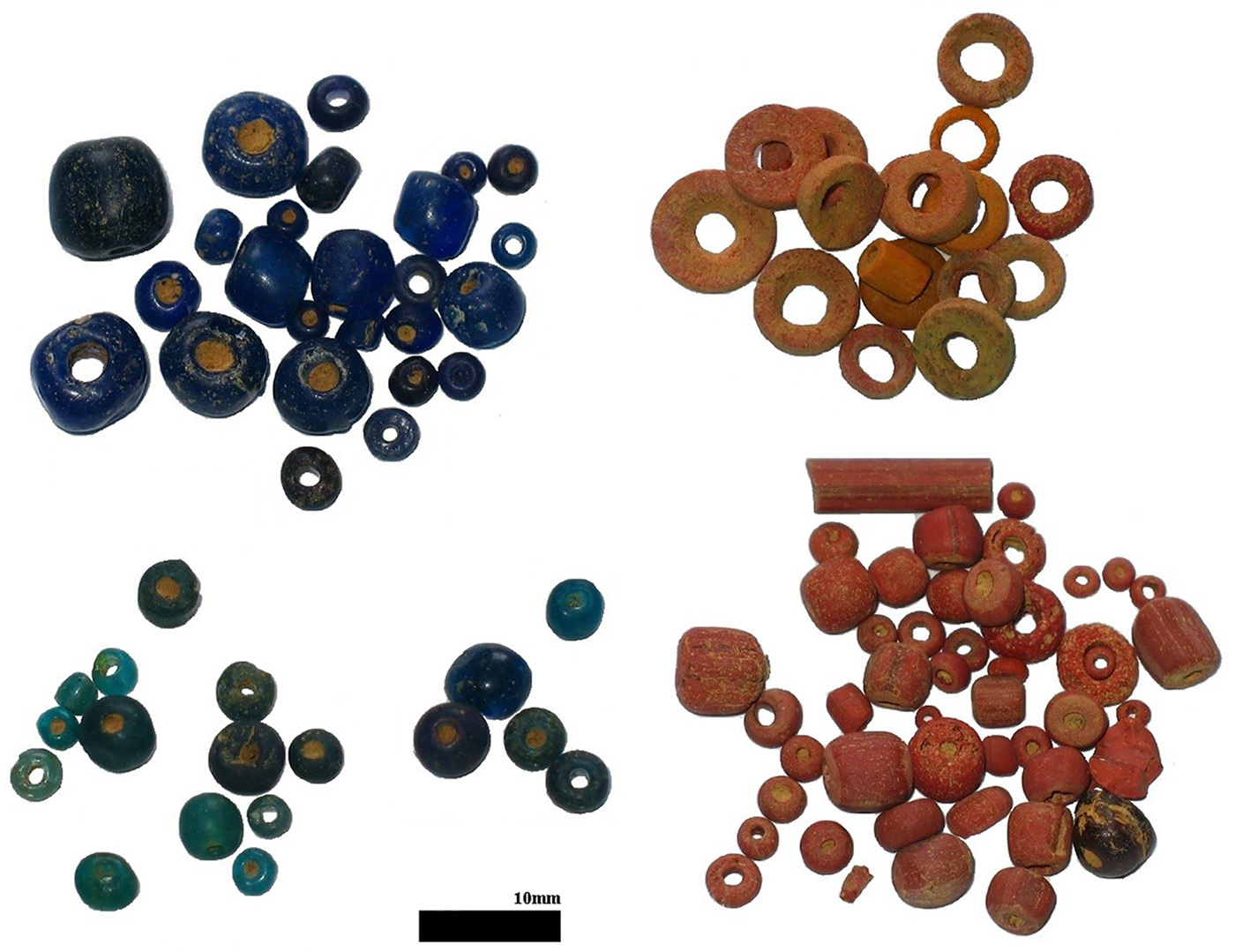

Figure 2. Individually catalogued glass beads from the site of Maliwan, some of which were analysed using LA-ICP-MS (credit: L. Dussubieux).

Terra incognita from an archaeological point of view until 15 years ago, the Kra Isthmus turned out to be a core region during the genesis of the Maritime Silk Roads. Research led by the French mission revealed that as early as the fourth century BC, cosmopolitan and proto-urbanised polities developed there. These early city-states played a crucial role in trade and cultural exchange, developing political and economic models that matured during the historical period from the eighth century AD. Port-cities were linked to upstream/inland extraction sites that provided primary resources (minerals, resins and timber) for long-distance trade, and also acted as way-stations for traders and other travellers crossing the Peninsula.

The two port settlements investigated by the Franco-Myanmar mission in 2018 were also part of this network. Maliwan is a large settlement established on a series of gently sloping hills located west of a tributary of the Kraburi River. It therefore does not overlook the Bay of Bengal and is protected from the monsoon winds. The two radiocarbon dates so far obtained (‘Beta 492589’ and ‘Beta 492590’) suggest an occupation from the fourth to second centuries BC, contemporaneous with the port-city of Khao Sam Kaeo (Bellina Reference Bellina2017) and its possible satellite, Khao Sek (Bellina & Sinopoli Reference Bellina and Sinopoli2018), on the Gulf of Siam coast. Maliwan provided evidence of habitation and craft production. Beads, rings and seals were produced from stones such as carnelian—possibly imported from India—and rock crystal and agate. Preliminary archaeometallurgical assessment suggests the presence of copper and multiple alloy traditions producing bronze and leaded bronze, as is seen on similar trade sites on the east coast. A lead isotope provenance study is ongoing.

The elemental composition was measured using laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS). Analysis of the glass artefacts confirms the early date of the site, with a combination of glass types similar to those found at Khao Sam Kaeo, Khao Sek and other sites dated from the fourth to second centuries BC. The glass material, however, has some very specific characteristics that suggest a direct connection with those very early glass sites is unlikely.

The preliminary analysis of the pottery highlights the existence of several production groups sharing technical similarities with the main local groups identified at Khao Sam Kaeo and Khao Sek. Indian Fine Grey pottery is also present, including some rouletted, incised and impressed sherds (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Top) local and Indian-related ceramic sherds found in Maliwan; bottom) fragments from Aw Gyi, sharing similarities with ceramics from India, China, the Philippines and Vietnam found in Aw Gyi (credit: A. Favereau).

Preliminary analysis of the archaeobotanical remains has identified domesticated rice and mungbeans in Maliwan. Mungbeans are of South Asian origin, and have also been found in Khao Sam Kaeo and Phu Khao Thong. The site also yielded terracotta female figurines, a worked stone ring with flower petals, a frieze of animals made in the Mauryan-Sunga style and several steatite-decorated vessels often referred to as reliquaries in India.

Aw Gyi is situated approximately 15km west of Maliwan, facing the Bay of Bengal, and consists of three hills bordered by a watercourse linking it to the sea. The settlement has been heavily looted but seems to have been occupied at a slightly later period, perhaps the early centuries AD. It yielded a lot of glass with elemental compositions found at other sites located around the Bay of Bengal such as Arikamedu in India and Phu Khao Thong in Thailand. In common with these two sites, fragments of glass from the Mediterranean area were found at Aw Gyi. This site also yielded evidence for stone working, as well as a large quantity of pottery fragments, some of which have parallels with those found to the east in southern Vietnam at Oc Eo, in China (Han period), in the Philippines (Kalanay-related), and west along the eastern coast of India (Fine Grey).

Further research is required on these two major port-settlements to understand their occupation sequences and wider relationships. Their study will greatly contribute to uncovering the still very poorly known history of the port-cities of the Bay of Bengal and their role in the earliest Maritime Silk Roads ports of Myanmar.