Introduction

In AD 749 a devastating earthquake destroyed large parts of the Levant, including large parts of the city of Jerash (Figure 1), the former Decapolis city known as Gerasa (Tsafrir & Foerster Reference Tsafrir and Foerster1992: 231–35). The impact of this earthquake has been discussed for decades, and various lines of evidence have been advanced to argue for or against the seriousness of the effect it had on the continuing urban life of Jerash after the mid eighth century AD (cf. Lichtenberger & Raja Reference Lichtenberger and Raja2016).

Figure 1. Plan of ancient Gerasa after Lepaon (Reference Lepaon2011), with the area of the Northwest Quarter marked in red.

Excavations have been undertaken in Gerasa for over 100 years (see Kraeling Reference Kraeling1938 for a summary of earlier explorations; and Lichtenberger & Raja Reference Lichtenberger and Raja2015a for additional references). From the beginning, the rich mosaic finds from the city were a key focus of the archaeological expeditions (Biebel Reference Biebel and Kraeling1938; Stinespring Reference Stinespring and Kraeling1938: 3). Most of the mosaics uncovered at Jerash date from Late Antiquity, but in 1907, during the earliest excavations at the site, a Roman mosaic was uncovered. It was split up into several parts and sent to museums in Berlin, Germany and Orange, Texas (Stinespring Reference Stinespring and Kraeling1938: 3; Talgam Reference Talgam2014: 49–52). Later, during the excavations focused particularly on churches, undertaken by John Winter Crowfoot (the director of the British School at Jerusalem), other mosaics were discovered, drawn and published (Crowfoot Reference Crowfoot and Kraeling1938: 171–264). The first chemical analysis of glass tesserae from mosaics in Jerash was undertaken by Dorothy Crowfoot, John's daughter, in 1929. She had been part of the 1928 expedition to Jerash (Stinespring Reference Stinespring and Kraeling1938: 6; Ferry Reference Ferry1998: 39–42). Some church mosaics were published in the volume edited by Carl H. Kraeling (Biebel Reference Biebel and Kraeling1938; Stinespring Reference Stinespring and Kraeling1938: 3), and mosaics from Jerash figured prominently in later studies (e.g. Piccirillo Reference Piccirillo1993; Balty Reference Balty1995: 111–40; Michel Reference Michel2001; Talgam Reference Talgam2014). Until today, however, no comprehensive study of the mosaics from the city has been undertaken, although a workshop has been identified in Gerasa (Balty Reference Balty1995: 135). In summary, the study of mosaics has been a focus within the research undertaken at Gerasa from the earliest excavations up until recent times, although there remains no singular comprehensive study.

In 2011 a Danish-German team began an archaeological project in the Northwest Quarter of Jerash (Figure 2), which is the highest area within the walled city (Lichtenberger & Raja Reference Lichtenberger and Raja2015a). This area, covering approximately 4ha, is scattered with ancient remains. Until recently it had remained largely unexplored apart from a few sondages laid out in the 1980s (Clark & Bowsher Reference Clark, Bowsher and Zayadine1986).

Figure 2. Plan of the Northwest Quarter with excavated trenches marked (A–Q) and the city wall highlighted in brown (© The Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project).

During the excavations, evidence for mosaics of different periods has been found. In most of the trenches, dislocated Roman, Byzantine and Early Islamic tesserae were encountered, attesting to the widespread use of this flooring technique throughout the Northwest Quarter. In 2015, large floors with mosaics were found in an ecclesiastical complex on the southern slope (Haensch et al. Reference Haensch, Lichtenberger and Raja2016; Kalaitzoglou et al. in press a). These floors carry extensive Greek inscriptions, dating the geometric mosaics to March 576 and July 591 AD respectively. Also on the southern slope, near a large multiphase cistern dating to the Roman period, waste material from mosaic production was found, offering information about the chaîne opératoire of the production methods (Kalaitzoglou et al. in press b). In the following, we discuss evidence for mosaic production dated to the Early Islamic period, which gives a rare insight into the practical organisation of production processes and craftsmanship.

The Eastern Terrace and the ‘House of the Tesserae’

During the recent years of excavation, it has become clear that the Northwest Quarter had dense Late Roman, Byzantine and Umayyad occupation strata (Barfod et al. Reference Barfod, Larsen, Lichtenberger and Raja2015; Lichtenberger & Raja Reference Lichtenberger and Raja2015b, Reference Lichtenberger and Rajain press). Occupation of the settlement came to an abrupt end with the mid eighth century AD earthquake, and reoccupation on a much more modest scale only took place during the Middle Islamic period (Lichtenberger & Raja Reference Lichtenberger and Raja2016). Unlike other areas of Jerash, in which some Abbasid rebuilding has been observed (Gawlikowski Reference Gawlikowski and Zayadine1986, Reference Gawlikowski2004; Walmsley et al. Reference Walmsley, Blanke, Damgaard, Mellah, McPhillips, Roenje, Simpson and Bessardal2008), the Northwest Quarter remained abandoned. On the Eastern Terrace of the Northwest Quarter, which overlooks the monumental Roman temple of Artemis, the earthquake of AD 749 sealed domestic complexes dating to the Umayyad period. When excavated, these turned out to contain full inventories of the houses as they had been before the earthquake struck (Lichtenberger & Raja Reference Lichtenberger and Rajain press). This area, covering approximately 3000m2, might almost be termed the ‘Pompeii of the East’, displaying frozen moments in time.

The houses were spacious and multi-storeyed with simple ground-floor rooms, such as kitchens and storage spaces, but also with some rooms carrying wall-painting and stucco decoration (Kalaitzoglou et al. in press a & Reference Kalaitzoglou, Lichtenberger and Rajab; Lichtenberger & Raja Reference Lichtenberger and Rajain press). The more elaborate rooms were, however, situated on the upper floors. In the so-called ‘House of the Scroll’ in trench K (Figure 3), which was both constructed and destroyed in the Umayyad period, numerous metal objects, decorated wall plaster and stucco elements were found (Lichtenberger & Raja Reference Lichtenberger and Rajain press). Among the rich finds were also a silver scroll amulet and a small coin hoard with Byzantine and Arab-Byzantine coins, as well as various pieces of jewellery (for the scroll, see Barfod et al. Reference Barfod, Larsen, Lichtenberger and Raja2015; for the coin hoard, see Lichtenberger & Raja Reference Lichtenberger and Raja2015b). Furthermore, there was pottery dating to the last phase of occupation before the earthquake (Lichtenberger et al. in press). Radiocarbon determinations on organic material confirmed the dating of the house to the first half of the eighth century AD. This is also supported by the discovery of so-called post-reform coins that date to after the coinage reform of Abd al-Malik at the end of the seventh century AD.

Figure 3. Photogrammetric composite image of the ‘House of the Scroll’, trench K. The numbers relate to different archaeological features (© The Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project).

In the 2015 excavations, parts of another domestic complex were excavated farther south (Kalaitzoglou et al. in press a). This so-called ‘House of the Tesserae’ (Figure 4), which was only partly excavated, was a domestic complex with rooms arranged around a courtyard. A staircase (no. 43 in Figure 4) led down to this courtyard in which there was a rock-cut cistern (no. 62 in Figure 4). An elaborate system for collecting water from the roof through pipes led vertically down the wall and into a channel (no. 97 in Figure 4) that fed the cistern. The complex was arranged on at least three different levels, and—as with the ‘House of the Scroll’—it was constructed in the Umayyad period and destroyed by the earthquake in AD 749, with no Byzantine or other earlier phases.

Figure 4. Photogrammetric composite image of the ‘House of the Tesserae’, trench P. The numbers relate to different archaeological features (© The Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project).

Two stages of building were detected in the construction of the ‘House of the Tesserae’. The original layout consisted of a rectangular eastern room, subdivided by an arch (no. 38 in Figure 4), and a nearly square room adjacent to the north-western room, also with an arch (no. 65 in Figure 4) that opened onto a courtyard. The eastern room had access to the courtyard through a door (no. 110 in Figure 4) in its south-western wall, and another door in the subdividing wall (no. 27 in Figure 4) also connected the eastern and north-western rooms. The southern part of the eastern room has not yet been excavated.

In the following phase, the house received new clay floors on which a hearth and other kitchen installations were built. Several architectural blocks, tumbled from the walls on the first floor, were found in the ground floor rooms. Some of these carried a thick layer of plaster (Figure 5), with regular cut marks and incisions, made in preparation for new wall decoration. Similar contemporaneous discoveries from Qasr Amra suggest that the cut marks and incisions were typical of ancient plaster underlay prior to the application of a second layer of plaster (Vibert-Guigue et al. Reference Vibert-Guigue, Bisheh and Imbert2007: pl. 7b). The cut marks serve to improve the attachment of the outer layer of plaster on which decoration was painted. This evidence suggests that the building was undergoing renovation when the earthquake struck, something that is further supported by the incompleteness of the household inventory as compared to the ‘House of the Scroll’. Therefore it seems that when the earthquake struck, this part of the house was not inhabited, but rather was used as a working space. The few finds and single AMS radiocarbon date of 1319±36 BP (sample no. 23931 (J15-Pc-69) Institut for Fysik og Astronomi, Aarhus University, Denmark: 650–770 AD at 95.4% probability; date modelled in OxCal, using IntCal13 calibration curve) clearly support the date of the house's destruction in the first half of the eighth century AD, suggesting a connection with the earthquake in AD 749. It seems that the house was undergoing reconstruction at the time the earthquake struck.

Figure 5. Photograph showing worked stone from the eastern room in the ‘House of the Tesserae’, trench P, with thick plaster layer bearing cut marks as preparation for the application of further layers of plaster decoration. One of the fallen mosaics from the upper storey is visible behind the stone with the plaster layer (© The Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project).

As with the ‘House of the Scroll’, the ground floor rooms seem to have been of a more utilitarian nature compared to those of the upper floor. Many large mosaic fragments were found in the debris of the lower room, having fallen from the upper floor (Figure 5). The weight load of this upper floor was originally carried by the stone arches beneath (e.g. nos 38 and 65 in Figure 4).

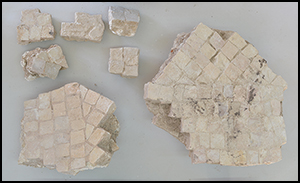

The most remarkable modification of the second phase was the installation of a trough in the eastern room, and the blocking of the door that connected it to the north-western room. The trough was constructed along the eastern side of the dividing wall containing the blocked door (Figure 4, no. 51; Figures 6–7). It was built of upright stone slabs that ran along the entire length of the dividing wall, and had a depth of 0.44m and a width of 0.4m. The trough servedfor the storage of tesserae; it was completely filled with thousands of pristine unused white tesserae (Figure 8).

Figure 6. Photogrammetric composite image showing the trough in the ‘House of the Tesserae’ from the east (© The Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project).

Figure 7. Photograph of the northern section of the tesserae trough in trench P (© The Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project).

Figure 8. Close-up photograph of some of the tesserae recovered from the trough in trench P (© The Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project).

The tesserae store

No similar installation for tesserae storage had ever been found before. In this case it is clear that the tesserae were unused and therefore part of the preparation for mosaic production. For a better understanding of the evidence, however, one must determine whether the installation was a temporary or permanent (longer-term) feature.

We have fairly detailed knowledge of the technical processes of laying mosaics, preparing the ground and the foundation, mixing mortar and laying tesserae, but little information about the organisational structures of the workshops themselves (Donderer Reference Donderer1989: 44–45, including the ambiguous evidence from Pompeii (De Vos Reference De Vos and Zevi1979: 166), which earlier has been interpreted as a workshop; see also Donderer Reference Donderer2008). Research in the Levant has hitherto been concerned mostly with characterising the style of mosaics in order to attribute them to particular workshops or schools (e.g. Ovadiah & Ovadiah Reference Ovadiah and Ovadiah1987; Hachlili Reference Hachlili2009; Talgam Reference Talgam2014; see also

Diklah Reference Diklah, Kristensen and Poulsen2012; Poulsen Reference Poulsen, Kristensen and Poulsen2012). Little has been published on the actual processes and spatial organisation of workshops. Several scholars have reflected on these issues, but usually with a focus on the finished mosaics and not on the production process (e.g. Ben Abed-Ben Khader Reference Ben Abed-Ben Khader, Paunier and Schmidt2001; Parrish Reference Parrish, Paunier and Schmidt2001; Sweetman Reference Sweetman, Paunier and Schmidt2001).

It is not known whether mosaicists had permanent studios where they stored their tools and materials, or whether they were mobile (semi or itinerant) and worked on site. Dunbabin (Reference Dunbabin1999: 281–82) argues that most mosaics were laid in situ. The epigraphic evidence relating to mosaicists mainly comes from inscriptions on mosaics where the craftsmen sometimes had inscribed their names (Donderer Reference Donderer1989, Reference Donderer2008). As no studio has yet been excavated, it is generally assumed that mosaic workshops were mobile, and that mosaicists worked where the mosaics were laid. Only emblemata, which were a detailed part of a mosaic that was prepared in a workshop, were pre-fabricated (Donderer Reference Donderer1989: 44–45; see also De Vos Reference De Vos and Zevi1979: 166, for a possible shop where a finished emblema was situated together with other objects). It is, however, almost certain that the tesserae from the house in Jerash were not intended for emblemata because they were usually laid with tiny precious stones and in several colours.

Mosaic production continued at an intense rate in the Byzantine and Early Islamic Near East, and there is evidence that the social status of mosaicists improved during these periods, as they were often mentioned in mosaic inscriptions alongside the names of the donors behind them, e.g. at Madaba, Nebo, Quweimeh and Umm er-Rasas (Donderer Reference Donderer2008: 32). This indicates that workshop organisation may generally have improved over time due to better economic circumstances.

There is already, from other sites, some evidence for the organisation of workshops. Coarse Byzantine and Early Islamic tesserae were cut on the location where the mosaics were laid. This is underlined by evidence from the Byzantine church in Masada, where a large quantity of rectangular, elongated stones were found. These are interpreted as raw material for the production of square tesserae (Yadin Reference Yadin1966: 112; for the Byzantine church, see Netzer Reference Netzer1991: 360–69). The tesserae were produced on location and used for mosaics in the church. At Beth Shean, two mosaic-production sites have been identified on a length of the street 200m south of the Roman theatre (Tzori Reference Tzori1953: 265; Ovadiah & Ovadiah Reference Ovadiah and Ovadiah1987: 39, cat. no. 37). Heaps of tesserae were found at one of these. Production waste close to the place where the mosaics were laid has been found at many other sites throughout the Roman world, and particularly in the west, including new material from the Iberian Peninsula (Donderer Reference Donderer1989: 45, cat. no. 195; Sanchez Velasco Reference Sanchez Velasco2000; Romero & Vargas Reference Romero and Vargas2011). There is also a unique fourth-century AD relief from Ostia (Figure 9), which is interpreted as showing a mosaic or tesserae workshop where the stones were made and then transported to shops or to the locations where the floors were to be laid (Zimmer Reference Zimmer1982: 36, cat. no. 81; Dunbabin Reference Dunbabin1999: 281). This suggests that the stones could have been cut somewhere other than where they were sold or laid. The relief from Ostia does not show permanent installations for storing tesserae, merely a heap of them lying on the floor.

Figure 9. Relief from Ostia Antica, showing workers in a mosaic or tesserae workshop facility (after Zimmer Reference Zimmer1982).

The trough in the house at Jerash clearly suggests a kind of storage intended for more than just short-term construction. It could be claimed, therefore, that we do indeed have a studio of a workshop with a tesserae storage facility in the room where craftsmen worked. Apart from the relief from Ostia, however, there is no other evidence that such tesserae workshops or shops existed, so an alternative interpretation seems ultimately more probable. We suggest instead that the house was undergoing thorough renovation at the time of the earthquake, and that the trough was installed for use during the restoration of the house.

The evidence from the ‘House of the Tesserae’ suggests that the trough served as a temporary installation for storing the tesserae until they were laid. That the decorated wall plaster had been prepared for new layers is a further indication that this complex was not a workshop studio, but rather a house in the midst of renovation. Similar situations are known from Pompeii, where houses were still undergoing reconstruction after the earthquake of AD 62 when Vesuvius erupted in AD 79 (Robotti Reference Robotti, Stern and Ginouvès1982).

As the house in Jerash was not completely excavated, some questions remain open. For example, no tools for mosaic-working were found in the excavated parts of the house. This might be due to the fact that the mosaicists who were working there had taken their tools with them when leaving at the end of the day, or perhaps they stored them in a hitherto unexcavated part of the house. Similarly, the question of where other materials, such as the mortar used for bedding the tesserae, were stored cannot be addressed fully until the rest of the house is excavated.

Another question that cannot be answered from the available evidence is where the mosaic was going to be laid. Circumstantial evidence can, however, shed some light on this matter. It is unlikely that the mosaic was intended to be placed in the same room as the trough, as the trough would have hindered that. Indeed, in the excavation of the ‘House of the Scroll’ close by, it became evident that the ground floors were quite simple, whereas the finds that had fallen from the upper floor show that that floor was decorated more elaborately. The same goes for the ‘House of the Tesserae’ where we have clear evidence for mosaics laid on the first floor. It is therefore conceivable that the tesserae were intended for the construction of a new mosaic on the first floor. This theory cannot be proved, however, and the possibility still exists that the tesserae were meant for use in another room in an unexcavated part of the house. That again will remain unresolved until the rest of the house is excavated.

Although many puzzling questions remain concerning the tesserae trough, it constitutes important evidence for the organisation of mosaic production in Early Islamic Jerash and throughout the ancient world in general. It offers a unique glimpse into the moment in time immediately before the earthquake struck. Moreover, it provides information about the use of temporary facilities in the production of mosaics. It is hoped that similar structures will be discovered in order to give a better understanding of the practical organisation of Late Antique mosaic workshops in the Levant.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Department of Antiquities in Amman and Jerash and its staff for facilitating our fieldwork in Jerash, and for continuously supporting our work. We would also like to thank the funding bodies who make our work in Jordan possible. These include the Carlsberg Foundation, the Danish National Research Foundation (grant number: DNRF 119), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and H.P. Hjerl Hansens Mindefondet for Dansk Palæstinaforskning. Thanks also go to all the members of the Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project team, and our special thanks go to Georg Kalaitzoglou (Head of Field) and Heike Möller (Head of Registration).