Introduction

Isla de Mona in the Caribbean preserves some of the most astonishing and under-researched evidence for indigenous-European interaction in the Americas. The archaeology of the island's caves provides an opportunity to study personal responses to an indigenous ritual landscape through evidence of the early translocation of Christianity to the New World. This article discusses a body of uniquely preserved inscriptions and iconography that captures the intimate dialogue of spiritual encounter between Christian and Native worldviews in the Caribbean. This unique and unorthodox ‘chronicle’ is examined through the archaeological, palaeographical and historical perspectives of early colonial encounters to situate the dialogue within the wider context of cultural interaction in the Americas.

The transformative potential of an archaeological perspective of the early arrival of Europeans and Africans in the indigenous Americas has become increasingly evident since the quincentennial of Columbus's landfall in the Caribbean (Lightfoot Reference Lightfoot1995; Deagan Reference Deagan and Cusick1998; Liebmann & Murphy Reference Liebmann and Murphy2011; Funari & Senatore Reference Funari and Senatore2015). Archaeological research has focused on indigenous perspectives that are under-represented in historic texts, breaking down traditional dichotomies of what ‘indigenous’, ‘Spanish’ or ‘mestizo’ means in colonial contexts in terms of material culture, landscape and identities (Voss & Casella Reference Voss and Casella2012; Hofman et al. Reference Hofman, Mol, Hoogland and Valcárcel Rojas2014; Silliman Reference Silliman2015). Increasing use of high-resolution material and archaeometric analyses have provided new understandings of colonial processes that are more nuanced than mere oppression, domination and, in the case of the Caribbean, indigenous extinction (Deagan Reference Deagan and Cusick1998; Lalueza-Fox et al. Reference Lalueza-Fox, Gilbert, Martinez-Fuentes, Calafell and Bertranpetit2003; Cooper et al. Reference Cooper, Martinón-Torres, Valcárcel Rojas, Hofman, Hoogland and Van Gijn2008). Archaeological perspectives on the ways that colonialism reconfigures landscapes and material relationships (Gosden Reference Gosden2004) reveal the forging of new material relationships and identities, be it in the re-use of European clothing and fastenings as jewellery by indigenous populations (Martinón-Torres et al. Reference Martinón-Torres, Valcárcel Rojas, Cooper and Rehren2007; Valcárcel Rojas Reference Valcárcel Rojas2016); the creolisation of religious beliefs in newly built churches (Graham Reference Graham2011); or coloniser familiarisation with new environments, foodways and ecologies (Deagan & Cruxent Reference Deagan and Cruxent2002; Rodríguez-Alegría Reference Rodríguez-Alegría2005). These each demonstrate that encounter left all sides changed: new identities and practices emerged in local contexts, underlining the importance of archaeological research to provide a counterpoint to grand narratives (Voss Reference Voss, Funari and Senatore2015). Here, we focus on archaeological evidence for religious engagement between European and indigenous individuals. We see how European perspectives were challenged by indigenous cosmology, and witness the creation of a highly personalised yet syncretic chronicle. This not only provides a counterpoint to official metropolitan histories, but also tracks the beginnings of new religious engagements and transforming cultural identities in the Americas.

Isla de Mona

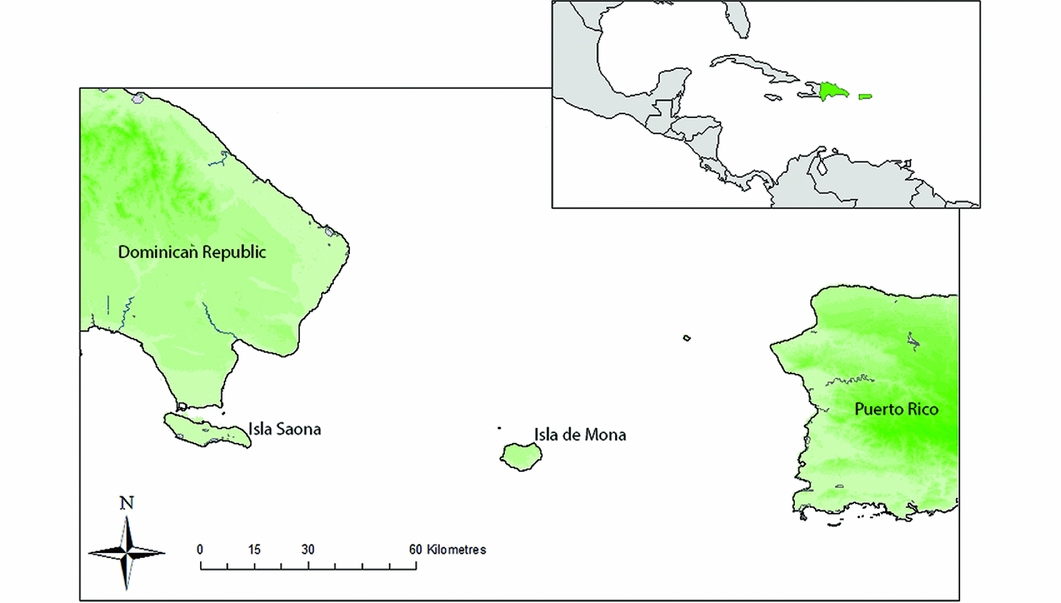

Christopher Columbus stopped at Isla de Mona on his second voyage in AD 1494 (Figure 1). Despite its small size (50km2) and seemingly isolated position between the islands of Hispaniola (native name Hayti) and Puerto Rico (Borinquen), Isla de Mona (Amona) played a crucial role in the establishment of the first European towns and the globalisation of the Caribbean. In AD 1494, one or more indigenous communities lived on Mona's coast, a day's canoe journey from the neighbouring, larger islands, tending agricultural plots and taking advantage of the abundant terrestrial and marine resources. Stone-lined plazas and a long history of the use of the island's many caves indicate that these communities were tied into inter-regional networks (Dávila Dávila Reference Dávila Dávila2003; Samson & Cooper Reference Samson and Cooper2015a).

Figure 1. Map of Isla de Mona in the Caribbean.

Accounts of Mona in early colonial documents (Samson & Cooper Reference Samson and Cooper2015b) identify that indigenous populations were fully immersed in direct contact with Europeans and Africans throughout the sixteenth century. This indio population experienced a generation of transformation as Spanish power was increasingly projected into the Caribbean. Islanders produced and exported agricultural products, especially cassava bread, and finished goods such as cotton shirts and hammocks for the first Spanish settlements, increasingly supplying food and water to European ships on their way to or from the Indies (Murga Sanz Reference Murga Sanz1960; Wadsworth Reference Wadsworth1973; Cardona Bonet Reference Cardona Bonet1985). Mona's location in the heart of Spanish colonial projects, and on one of the main Atlantic routes from Europe to the Americas, allowed inhabitants to exploit the opportunities of this early colonial world. Communities on Mona were exposed to the earliest waves of European impact at a time when Europeans themselves were in an alien environment, gathering knowledge, making decisions and learning patterns of behaviour that became more firmly entrenched as the colonisation of the Americas continued. This was a critical period of creolisation in which the first and subsequent generations of inter-continental Americans were born; there is therefore great potential for the archaeology of Mona to provide insights into the transformation and forging of new identities.

Indigenous Amona

Archaeological evidence of an indigenous presence on Mona spans over 5000 years (Dávila Dávila Reference Dávila Dávila2003; Samson & Cooper Reference Samson and Cooper2015b). The population that witnessed Columbus's ships was part of a large, complex cultural network of territorially, genetically, linguistically and artistically interwoven chiefdoms stretching from the Bahamas to the Lesser Antilles, with some population estimates for Hispaniola alone of over one million people, and for Puerto Rico of 100000 (Anderson-Córdova Reference Anderson-Córdova1990; Rouse Reference Rouse1992; Moscoso Reference Moscoso2008). During later pre-Columbian times, from AD 500, Mona was a hub of interaction between the chiefdoms of Borinquen and Hayti. From AD 1300–1500, a spike in evidence for cave exploration suggests the island's subterranean spaces were a major draw; cave practices were instrumental in late pre-Columbian ethnogenesis. The earliest Spanish accounts of Mona emphasise Spanish dependence on indigenous labour and products (Fernández de Oviedo y Valdéz Reference Fernández de Oviedo y Valdéz1851: 16: 1; Samson & Cooper Reference Samson and Cooper2015b).

European encounter on Mona

The adoption of European material culture, products and technology on Mona was immediate and profound. During recent fieldwork, European objects recovered within indigenous settlements and activity areas include glass beads (Figure 2), new types of European storage jars, ceramic vessels and monetary currency at sites along the south coast and inland. Imports spanning the period from AD 1493–1590 are found in residential settlements, agricultural fields and cave refugia. The presence of European ceramics and livestock, and Spanish coins in direct association with indigenous ceramics, tools and food-processing equipment, reflects this changing material world and indigenous transculturation (Dávila Dávila Reference Dávila Dávila2003; Cooper et al. Reference Cooper, Martinón-Torres, Valcárcel Rojas, Hofman, Hoogland and Van Gijn2008). As a counterpart to technological and economic transformation, however, the subterranean landscape of Mona reveals extraordinary material evidence of the face-to-face ontological encounter, providing a window into the spaces and experiences of the spiritual transformation.

Figure 2. Early colonial Nueva Cadiz bead discovered at Playa Sardinera on Isla de Mona.

Caves of Mona

Isla de Mona is one of the most cavernous regions, per square kilometre, in the world (Frank et al. Reference Frank, Mylroie, Troester, Alexander and Carew1998). Limestone cliffs dominate, providing access to the island's 200 Pliocene-era cave systems in the geological interface between the hard, lower Isla de Mona Dolomite and the porous, upper Lirio Limestone (Kambesis Reference Kambesis2011; Lace Reference Lace2012, Reference Lace2013). The caves exponentially increase the experience of the island's size, providing access to a subterranean realm that is often more easily traversed than the densely vegetated world above. Caves on Mona provide a palimpsest of human activity spanning the pre-Columbian past to the present day, with clearly identifiable peaks in human cave use (Samson et al. Reference Samson, Cooper, Nieves, Wrapson, Redhouse, Vieten, de Jesús Rullan, López de Victoria, Gómez, Serrano Puigdoller, Ortiz and de Jesús2015). The importance of caves within the spiritual or, from a European perspective, ‘religious’ framework of indigenous populations across the Americas is well established (Brady & Prufer Reference Brady and Prufer2005; Moyes Reference Moyes2013). In the Caribbean, late-fifteenth-century accounts collected from indigenous informants on Hispaniola relate the emergence and origins of the first humans from two separate caves (Pané Reference Pané1999). Indeed, archaeological evidence from across the archipelago shows that caves were used for purposes such as the deposition of human remains and social valuables, and as locations of symbolic iconography.

Since 2013, archaeological survey of around 70 cave systems—part of an interdisciplinary study of past human activity on Isla de Mona—has revealed that Mona's caves provided a range of symbolic, economic and subsistence resources to residents and visitors, and to indigenous and historic populations. Indigenous presence has been identified in 30 cave systems around the island. Evidence includes the greatest diversity of preserved indigenous iconography in the Caribbean, with thousands of motifs recorded in darkzone chambers far from cave entrances (Lace Reference Lace2012; Samson et al. Reference Samson, Cooper, Nieves, Rodríguez Ramos, Kambesis and Lace2013; Samson & Cooper Reference Samson and Cooper2015b). Marks consist of geometric motifs, meanders and areas where the soft cave crusts have been deliberately and systematically removed, as well as extensive and complex imagery of anthrozoomorphic and ancestral beings (cemíes) (Figure 3). Cave chambers both large (>50m in diameter) and small (<1m wide), their surfaces covered with iconography, must have been a unique architectural experience for indigenous populations, and very different from the biodegradable and permeable domestic architecture of their settlements (Cooper et al. Reference Cooper, Valcárcel Rojas, Calvera Rosés, Kepecs, Curet and Rosa2010; Samson Reference Samson, Keegan, Hofman and Ramos2013).

Figure 3. Indigenous iconography from cave 18 showing ancestral beings and anthrozoomorphic figures.

As well as being symbolic locations, caves on Mona contain important subsistence resources, such as the only sources of permanent fresh water. There is a clear association between underground sources of fresh water and concentrations of indigenous mark-making (Lace Reference Lace2012). The role of the caves as a source of life-giving water is referenced in the iconography (Figure 4). The markings on the cave walls and extraordinary acoustic, olfactory and haptic properties of the environment offer a powerful experience of alterity, enhanced by the lack of usual sensory stimulation, disorientating and heightening awareness, and morphing perspectives of space and time (Siffre Reference Siffre1964). Hundreds of metres underground, torch or lamplight flickering across representations of cemíes on walls and ceilings, some reflected in pools of water, would have made a powerful impression on all visitors to the caves.

Figure 4. Indigenous mark-making and its relation to sources of water in chamber E.

Cave 18

In this paper, we focus on archaeological, chronometric, palaeographical and historical evidence for a series of early to mid-sixteenth-century cave visits that illuminate previously unknown aspects of the indigenous-European spiritual encounter.

Cave 18 is on the south coast of Mona, reached by traversing the foot of a cliff, climbing a vertiginous cliff face and scrambling through a human-sized entrance. Chambers and tunnels run for more than 1km. Around half a dozen balcony entrances in the cliff face provide access to dendritic pathways leading back to deep, darkzone cave chambers. Tunnels emerge into a series of low rooms, high vaulted chambers and areas of water pools and flowstone. After around 50m of walking, in darkness, one encounters the material record of indigenous, followed by historic, mark-making.

Indigenous mark-making

Evidence of indigenous activity occurs within a large yet delimited darkzone area in chambers A–K (Figures 3 & 4). Around 250 separate motifs, made by dragging one to four fingers (‘finger-fluting’), and finger-sized tools through the soft deposits of the cave surfaces, cover the walls, ceilings and alcoves in 10 chambers and interconnecting tunnels over some 6500m2— about 15 per cent of the cave system. Execution of the imagery necessitated climbing and crouching to reach desired surfaces. The indigenous origin of the marks is supported by the clearly identifiable styles of Late Ceramic Age iconography, as well as from Capá (thirteenth- to sixteenth-century) pottery found in the same chambers (Figure 5). Two radiocarbon dates (OxA-31209 & OxA-31536) from charcoal (Amyris elemifera and Bursera simaruba) recovered from untrammelled edges of two separate chambers (Figure 6) date to the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries (1272–1387 cal AD, and 1420–1458 cal AD at 95.4% confidence, in Oxcal v4.2, using IntCal13 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013)).

Figure 5. Indigenous ceramics from cave 18 with similar iconography from cave 12 on the other side of the island.

Figure 6. Map of cave 18 showing the locations and spatial relationships between the indigenous iconography and post-contact inscriptions.

Historic mark-making

More than 30 historic inscriptions in cave 18 include phrases in Latin and Spanish, names, dates and Christian symbols that occur within a series of connecting chambers (Figure 6), all within the area of indigenous iconography. Where both occur together, the average height above the floor of the historic marks is 1.8m, compared to 1.5m for indigenous marks. There are no indigenous marks overlaying written inscriptions or Christian symbols. The majority of the inscriptions are single-lined strokes, created by a variety of edged tools, and thus distinct from the finger-fluted indigenous marks. The Christian imagery and inscriptions are predominantly at or above (European) head height, occupying flat, vertical wall surfaces and visible while walking upright through the space, distinct from the lower positions and multiple orientations of indigenous marks.

Three inscribed phrases are present in chambers H and K: ‘Plura fecit deus’, ‘dios te perdone’ and ‘verbum caro factum est (bernardo)’. Palaeographic analysis of letter forms, the use of abbreviation and writing conventions place these in the sixteenth century (Samson et al. in press). ‘Plura fecit deus’, or ‘God made many things’, is the first inscription encountered after entering chamber H. There is no obvious contemporary textual source; the commentary appears to be a spontaneous response to whatever the visitor experienced in the cave. There is a strong spatial inference that ‘things’ is a reference to the extensive indigenous iconography present. The phrase may express the theological crisis of the New World discovery, throwing the personal human experience and reaction into sharp relief.

In the next chamber, the phrase ‘dios te perdone’, ‘may God forgive you’, is inscribed on a ceiling protuberance surrounded by extensive indigenous finger-fluting (Figure 7). This is a common Christian petition, which implies a separation between the author and the subjects, or acts that require forgiveness, and the intercessional role of the author, perhaps akin to a confessional pardon between priest and sinner. Another implication is that the attendant practices, now invisible to us, require forgiveness as well as the images themselves.

Figure 7. Spanish inscription in cave 18 that reads ‘dios te perdone’, God forgive you.

The third Latin inscription, ‘verbum caro factum est’, is a direct quotation from the Vulgate version of the bible, the Gospel of John 1:14, “And the Word was made flesh [and dwelt among us]”. The biblical passage follows a description of the creation of the world, and is the first announcement of Jesus (the Word) in the Gospel, followed by his baptism. This well-known chapter of the Bible would have been familiar even to Christians without formal Latin education (Richard Rex, pers. comm. 2015).

Particularly striking are two depictions of Calvary. The first consists of three crosses, the central one with the Latin inscription ‘Iesus’ (Jesus) set at a height of over 3m in chamber G (Figure 8). Stylistically, all three are barred cross-on-base motifs, in use in the sixteenth century; similar examples are found from contemporary contexts in Europe and South America (McCarthy Reference McCarthy1990; Hostnig Reference Hostnig2004; Barrera Maturana Reference Barrera Maturana2011; Tarble de Scaramelli Reference Tarble de Scaramelli, Voss and Casella2012). A second Calvary panel is made up of two crosses, one of which is a barred cross-on-base, the other a simple two-stroke Latin cross. These flank a pre-existing indigenous anthropomorphic figure. This triptych has clear compositional parallels with representations of Calvary in which the central figure is strikingly cast as an indigenous Jesus.

Figure 8. A Christian Calvary in cave 18 with the name Jesus under the central cross.

Reinforcing the distinctly Christian character of the inscriptions are a series of 17 crosses, ranging from simple Latin crosses to more complex Calvary crucifixes (Figure 9). Crosses appear alone and in direct association with names and phrases, and most often close to indigenous finger-fluting and iconography. Analyses of stroke sequences demonstrate that the vertical line is drawn first, then the horizontal line added from left to right, in the gesture of a right-handed blessing. Crosses are placed in visually dominant positions over cave entrances or on high walls, most being set vertically above indigenous iconography rather than superimposed. This vertical ordering is a clear and cross-culturally understood visual convention of hierarchical relations, and seen elsewhere in rock art sites across the Americas (Hostnig Reference Hostnig2004; Martínez Cereceda Reference Martínez Cereceda2009; Tarble de Scaramelli Reference Tarble de Scaramelli, Voss and Casella2012; Recalde & González Navarro Reference Recalde and González Navarro2015). Although indigenous cross motifs are common across the Antilles and Andean region, these are distinct, often framed, equal-armed crosses, produced in a different way in terms of directionality, style, method and location (Dubelaar Reference Dubelaar1986: 102).

Figure 9. Selection of three Christian crosses found in cave 18 with stroke directions indicated.

Simple crosses are also found adjacent to a series of Christograms (Figure 10), abbreviated forms of the name of Jesus Christ, which had been in use for over a millennium when these examples were incised in the walls of the cave. The Christograms employed on Mona used Latin and Greek characters to form a symbology of Christ's name, and these were in common usage from early medieval periods. The simplest form found in cave 18 is IHS, the first letters of Jesus in the Greek alphabet. A more complex form is the abbreviatedform of ‘Jesus’, ‘IHS’, followed by a cross and then ‘XPS’, or chi-rho-sigma for ‘Christ’. In all cases, the ‘H’ has a cross above it, also common in late medieval Christograms. The name of Christ engraved into the walls of the cave materialises a Christian characterisation of the space. The dominance of the Christ figure (as opposed to Mary or another saint) confers a Christocentric devotional character that was rooted in late medieval tradition and became increasingly popular in New World shrines throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (Nolan Reference Nolan, Crumrine and Morinis1991; Taylor Reference Taylor2010).

Figure 10. An IHS Christogram that uses the first three letters of Jesus in the Greek alphabet to reference Jesus Christ.

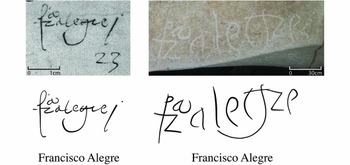

In addition to Christian symbolism and religious commentary, the cave walls also bear a series of dated and named individuals. These include Myguel Rypoll 1550, Alonso Pérez Roldan el Mozo 1550 August and Alonso de Contreras 1554. Other sixteenth-century visitors include a canon (an ecclesiastical office), an individual named Bernardo, who added his name to the inscription ‘verbum caro factum est’ and an anonymous visitor in February 1554. A Capitán Francisco Alegre wrote his name prominently in chamber K.

Archival research

Many of the names on the cave surfaces are not listed in the official texts referring to the initial Spanish occupation of Mona. Searches of the early colonial chronicles, passenger lists to the Indies from 1500–1590, relevant sections of the digitised archives of Seville, and the Documentos de la Real Hacienda de Puerto Rico were consulted for individuals with connections to Mona, including the Baptismal-indigenous name combinations and Spanish rank titles of over 100 indios. The most secure identification is for Francisco Alegre, who has been identified in historical documents—and on the basis of handwriting similarities (Figure 11)—as having emigrated with his father to the Indies in the 1530s from Spain. Alegre became a prominent citizen (vecino) of San Juan and held a number of royal functions in Puerto Rico throughout the sixteenth century, including that of factor, in charge of royal estates, among which was Isla de Mona (Archivo General de Indias 1550).

Figure 11. The name of Capitán Francisco Alegre, royal official of Puerto Rico in the mid-sixteenth century; note the similarities between the writing on the cave wall and his name in an archival manuscript from AD 1550.

Discussion—‘The Mona Chronicle’

In the sixteenth century, the persistence of Mona's indio population, their relative autonomy and the island's geopolitical position in a trans-Atlantic and Caribbean maritime thoroughfare created the conditions for a century of spiritual encounter. The corpus of post-contact inscriptions and their physical interrelationship with indigenous iconography and practices strongly suggests authorship by people of European descent visiting Isla de Mona from the neighbouring Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico and Hispaniola. The position, relative sequencing, production methods, written dates and content of the mark-making, as well as the biographic identification of Francisco Alegre, support this interpretation. Indigenous iconography, ceramics and two radiocarbon dates indicate that the cave was used by indigenous people during the mid fifteenth century, directly preceding European arrival. The presence of a historically documented church in the Sardinera village in AD 1548 (Dávila Dávila Reference Dávila Dávila2003: 33), administered by indigenous converts, suggests that indigenous Christians were themselves directly engaged with this arrival of a new ideology and associated visual culture. It is possible that some of the finger-drawn crosses in cave 18 may have been executed by indios conversos (indigenous peoples converting to Christianity), as has been proposed for the colonial Andes (Hostnig Reference Hostnig2004). Further research will consider whether at least some of the historic inscriptions and names may belong to indigenous individuals. Certainly, access to both the cave and the relevant chambers necessitated preparation and knowledge of local geography. The presence of over half a dozen named individuals, different dates and the diversity of handwriting indicates multiple visits over time, most notably in the 1550s. The fact that cave 18 was singled out from the nearly 30 currently known caves with indigenous activity on Mona implies that it was an established and meaningful indigenous space at the time of contact, and this was the impetus for its continued use into colonial times.

New generations of Americans of diverse cultural heritage began to differentiate themselves from the cultures of the European metropole, and new identities such as indio and creole are recognised as early as 1514 in historic records (Moscoso Reference Moscoso2010). It is within this context that the first generation of Europeans and Christian indios from diverse American homelands visited Mona's cave 18. At least some of the authors were elite males of Spanish ancestry, knowledgeable about certain aspects of indigenous culture, conversant with indigenous beliefs and willing to engage with them. The presence of a canon, and those with basic literacy and education, suggests both lay figures and church officials made journeys to the cave.

One must consider the range of motivations for such visits. There were economic advantages to alliances with the indio community on Mona, which was still an important centre of cassava production in the second half of the sixteenth century. Similarly, indios may have gained economic and political advantages by pursuing alliances with vecinos such as Francisco Alegre. Beyond economic motivations, the construction of new colonial landscapes may have been related to the emergence of an indio converso identity, especially after the end of Spanish encomienda (where designated territories were given by the crown to individual European colonists to manage and administer) around 1546. Further, from a coloniser perspective, the founding of local Christian shrines was essential to carving out a local Caribbean identity, drawing on indigenous traditions, in line with a post-reformation trend for shrine formation (Nolan Reference Nolan, Crumrine and Morinis1991; Coleman & Elsner Reference Coleman and Elsner1995; Stopford Reference Stopford1999). The interaction between Christian commentary and indigenous imagery represents individual responses and a degree of mutual understanding, rather than a coherent programme or formal liturgy. Visitors engaged with cross-cultural preoccupations such as concepts of origins (expressed in phrases such as plura fecit deus), the afterlife (images of the crucifixion), the hierarchy of belief systems (the crosses on top of indigenous marks), and the place of the individual (names and dates). The emotional and theological character of the inscriptions is different from the censure of the inquisition in places such as contemporary Mexico, where the incorporation of indigenous iconography into a Calvary scene (Figure 12) would have been deeply heretical. Moreover, from an indigenous perspective, the lack of clear evidence for resistance, such as the depictions of cross-bearing Spanish horsemen from indigenous rock art in the Andes (Gallardo et al. Reference Gallardo, Castro and Miranda1990; Martínez Cereceda Reference Martínez Cereceda2009), and the lack of explicit continuity of traditional visual codes, points to a degree of ownership of new beliefs and practices.

Figure 12. Christian cross in a niche of cave 18, directly facing an indigenous ancestral figure.

The historical legacy of 1492 fixates upon and fetishises the incompatibility of native and European worldviews, leading to a one-sided picture of the spiritual conquest of the Americas, exacerbated by native ‘extinction’ in the Caribbean. Moreover, the sheer continental scale of colonisation means that grand narratives dominate our image of encounter. The individual narrative of the people who actually made these encounters operate at a temporal resolution of minutes, hours and days as revealed within this cave. These experiences are what frame early colonial attitudes and create the pathways of encounter, not from indigenous and European perspectives, but from an emerging generation of Americans. The unorthodox ‘Mona Chronicle’, a multi-authored account of the spiritual encounter, provides a rare insight into intercultural religious dynamics in the early Americas.

Corollary

In 1550, King Charles V of Spain presided over a theological debate in Valladolid (Las Casas-Sepúlveda debate) about whether the Indians of the New World had rational souls (Hanke Reference Hanke1974). In the same year, Alonso Pérez Roldan the Younger and Myguel Rypoll partook in a procession to a local shrine, etched their names onto the walls of a cave chamber and joined a debate in this cave about the compatibility of the Catholic God and ancestral spirits with the indios who led them there. The contrast between the formal, intellectual, metropolitan debate, immortalised in paper archives, and the dialogue between colonial individuals of diverse origins, materialised in stone, could not be greater. Nevertheless, both express the metaphysical schisms, anxieties, social experiments and transformations engendered on all sides by the European-American encounters (Hanke Reference Hanke1974; Boxer Reference Boxer1978). It is often said that there was no conclusive outcome to the Valladolid debate. Its Caribbean counterpart on the other hand, a personal debate reflected within the Mona Chronicle of cave 18, had some clearly identifiable outcomes with arguably one of the first manifestations of a creole Christian identity in the New World. These discoveries and their interpretation reveal a process by which new identities are forged in this greatest of cultural encounters, and they provide insight into the creation of new cultural identities throughout the Americas.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted with the support of the British Museum Research Committee, the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research (University of Cambridge), the Centro de Investigaciones Históricas (University of Puerto Rico-Río Piedras), the Instituto de Cultural Puertorriqueña, Departamento de Recursos Naturales y Ambientales de Puerto Rico, the British Academy and the Centro de Estudios Avanzados de Puerto Rico y El Caribe. We are also indebted to Herb Allen III, Monica de la Torre, Delise Torres, Osvaldo de Jesús, Victor Serrano, Alex Palermo, Angel Vega, Paola Schiappacasse, Kate Jarvis, Tiana García, Daniel Shelley, Rolf Vieten, Lucy Wrapson, David Redhouse, Tom Higham, Jose Rivera, Walter Cardona Bonet, Ovidio Dávila Dávila and Miguel Bonet for their contributions to this research. Further thanks are due to Amy Maitland Gardner for the figures, and to the Natural Environment Research Council, Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (Grant NF/2014/2/7) and the British Cave Research Association (Grant CSTRI-2014).